Adherent Cell Detachment: Techniques, Challenges, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of adherent cell detachment, a critical yet challenging step in cell culture for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Adherent Cell Detachment: Techniques, Challenges, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of adherent cell detachment, a critical yet challenging step in cell culture for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational science of cell adhesion, details established and emerging detachment methodologies, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and presents a comparative analysis of techniques to validate their impact on cell viability, surface markers, and downstream applications. The scope extends from routine subculturing to the demands of large-scale biomanufacturing for cell therapies and regenerative medicine.

The Science of Cell Adhesion: Why Detaching Cells is a Fundamental Challenge

Defining Adherent Cells and Anchorage Dependence in Cell Culture

Adherent cell cultures represent a fundamental methodology in biological research and biomanufacturing, defined by the requirement for cells to attach to a solid, growth-promoting surface in order to proliferate—a biological imperative known as "anchorage dependence" [1] [2]. This cellular behavior contrasts sharply with suspension cultures, where cells proliferate freely in liquid medium without surface attachment requirements. Most vertebrate-derived cells (with the notable exception of hematopoietic cells) are anchorage-dependent, requiring a two-dimensional monolayer to facilitate the essential processes of cell adhesion, spreading, and replication [2]. These morphological characteristics form the basis of cellular classification in culture, with fibroblast-like cells exhibiting a linear, stretched shape and migratory behavior when attached, while epithelial-like cells display a wider, polygonal morphology and remain relatively stationary on the monolayer [2].

The biological significance of anchorage dependence extends beyond simple physical attachment. Normal, non-transformed tissue-derived cells (including most stem cells) absolutely require this culture support for self-renewal and differentiation, with its absence triggering growth arrest and induction of anoikis—a specific form of programmed cell death induced when anchorage-dependent cells detach from their surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) [3]. This critical dependency positions adherent cell culture as an indispensable technology across virology, drug discovery, regenerative medicine, and basic biological research, with recent advancements in detachment methodologies addressing long-standing challenges in cell viability, phenotype preservation, and process scalability [3] [4].

Biological Principles of Anchorage Dependence

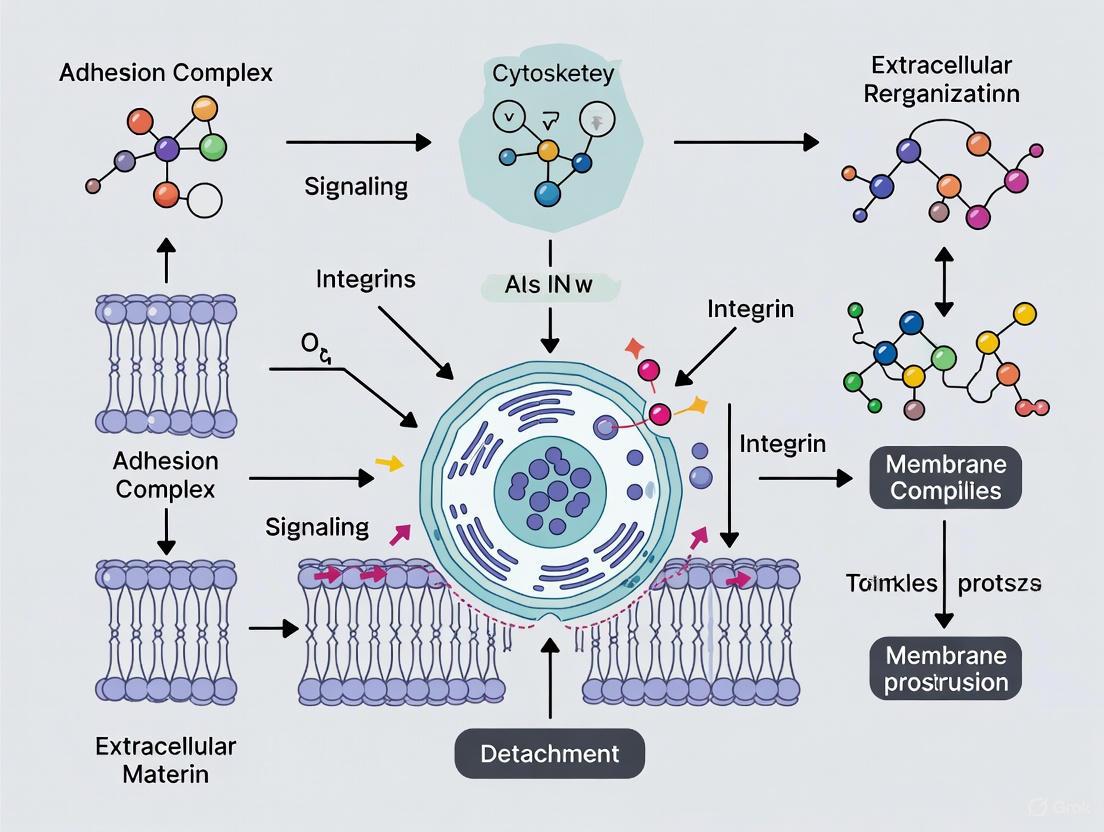

Molecular Mechanisms of Cell Adhesion

The anchorage dependence of cells is mediated through sophisticated molecular machinery that connects the extracellular environment to intracellular signaling pathways. Integrins—transmembrane receptor proteins—serve as the primary mediators of cell adhesion by binding to specific ligands in the extracellular matrix and to cytoskeletal components within the cell. This bidirectional signaling not only provides structural anchorage but also transmits critical survival and proliferation signals that prevent anoikis [3]. The adhesion process involves sequential engagement of adhesion receptors, clustering of integrins at focal adhesion sites, and activation of intracellular signaling cascades that regulate cell cycle progression and metabolic activity.

Calcium ions play a crucial role in maintaining integrin-mediated adhesion, which explains the effectiveness of calcium chelators like EDTA in cell detachment protocols [5]. The mechanical properties of the substrate, including its stiffness and topography, are actively sensed by cells through these adhesion complexes and influence diverse cellular behaviors including migration, differentiation, and gene expression. This mechanotransduction capability means that adherent cells not only respond to biochemical cues but also to the physical properties of their attachment surface, creating a complex regulatory network that governs cell fate decisions in both physiological and culture conditions [3].

Implications for Research and Therapy

The anchorage-dependent nature of most primary cells carries profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development. In contrast to transformed tumor cells that often proliferate independently of attachment, normal cells require appropriate adhesion signaling to maintain viability and function, making faithful recapitulation of these signals essential for physiologically relevant culture models [3]. This requirement becomes particularly critical in stem cell research and regenerative medicine, where the culture environment must mimic natural stem cell niches containing appropriate surface-bound signaling factors, cell-cell contacts, ECM components, and biomechanical microenvironments to maintain pluripotency or direct differentiation along specific lineages [3].

The dependency on adhesion signaling also creates significant challenges for large-scale biomanufacturing processes. Traditional two-dimensional culture systems face inherent limitations in surface-area-to-volume ratios, restricting cell yield and necessitating the development of specialized technologies like microcarriers and fixed-bed reactors for industrial-scale applications [3]. Furthermore, the sensitivity of adherent cells to shear stress in bioreactor environments requires careful engineering of culture conditions to maintain viability and functionality while achieving necessary production scales for vaccines, cell therapies, and other biological products [3].

Established Cell Detachment Methodologies

The requirement to periodically detach adherent cells for subculturing or analysis has led to the development of various methodological approaches, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and effects on cellular properties. These methods can be broadly categorized as enzymatic, non-enzymatic, and mechanical techniques.

Enzymatic Detachment Methods

Enzymatic detachment remains the most widely used approach for dissociating adherent cells, utilizing proteolytic enzymes to cleave the proteins mediating cell-surface attachment.

Trypsin: The historical gold standard for cell detachment, trypsin cleaves peptides after lysine or arginine residues, effectively degrading most cell surface proteins and extracellular matrix components. The procedure involves washing cells with a balanced salt solution without calcium and magnesium to remove serum inhibitors, followed by application of pre-warmed trypsin (approximately 0.5 mL per 10 cm²) and incubation at room temperature for 2-5 minutes until ≥90% of cells have detached [1]. The enzymatic action is then neutralized with complete growth medium containing serum, and cells are centrifuged (200 × g for 5-10 minutes) before resuspension and counting [1]. While efficient, trypsinization causes substantial damage to surface proteins and requires careful control of incubation time to maintain cell viability.

Accutase: Considered a milder enzymatic alternative, Accutase is formulated for gentle detachment while better preserving cell surface markers [5] [6]. It contains proteolytic activity that gently breaks down cellular adhesion molecules and offers the practical advantage of not requiring neutralization or wash steps [6]. However, recent research has revealed that Accutase can compromise specific surface proteins, notably causing significant decreases in surface Fas ligands and Fas receptors by cleaving them into fragments [5]. Surface expression of these proteins requires approximately 20 hours to recover after Accutase treatment, highlighting the importance of allowing adequate recovery time before experiments investigating these markers [5].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Enzymatic Cell Detachment Reagents

| Reagent | Mechanism of Action | Incubation Conditions | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | Cleaves after lysine/arginine residues | 2-5 minutes at room temperature [1] | Highly efficient; well-established protocol | Damages most surface proteins; requires serum neutralization |

| Accutase | Proteolytic blend with collagenolytic and DNase activities | Ready to use once thawed; do not pre-warm to 37°C [6] | Gentle on cells; no neutralization required | Compromises specific surface proteins (FasL, Fas); requires recovery time [5] |

| TrypLE | Recombinant fungal trypsin-like protease | Similar to trypsin [1] | Animal-origin free; consistent performance | Variable efficiency across cell types |

Non-enzymatic and Mechanical Methods

Non-enzymatic approaches offer alternatives that avoid proteolytic damage to cell surfaces, preserving important markers and functions.

EDTA-Based Solutions: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) facilitates cell detachment by chelating calcium ions essential for integrin-mediated adhesion [5]. This method is considered mild and better preserves surface protein integrity, as demonstrated by maintained expression of Fas ligands and Fas receptors compared to enzymatic treatments [5]. However, EDTA alone is often insufficient for strongly adherent cells and frequently requires mechanical assistance through scraping or pipetting, which can potentially damage cells through mechanical stress.

Cell Scraping: This purely mechanical approach involves physically dislodging cells using a sterile scraper tool. Research indicates that scraping preserves the highest levels of surface FasL expression compared to both enzymatic and chemical detachment methods [5]. The significant drawback is the potential for substantial cellular damage, reduced viability, and generation of heterogeneous cell populations due to variable application of mechanical force.

Novel Electrochemical Approach: Recent innovation from MIT introduces an enzyme-free strategy using alternating electrochemical current on a conductive biocompatible polymer nanocomposite surface [4]. By applying low-frequency alternating voltage, this platform disrupts adhesion within minutes while maintaining over 90% cell viability, addressing limitations of both enzymatic and mechanical methods [4]. The approach demonstrates 95% detachment efficiency for human cancer cells (osteosarcoma and ovarian cancer) while minimizing waste and compatibility concerns associated with animal-derived enzymes, showing particular promise for large-scale biomanufacturing and automated workflows [4].

Diagram 1: Cell Detachment Method Selection Workflow. This decision tree illustrates the systematic selection of detachment methods based on experimental requirements and cell type considerations.

Quantitative Comparison of Detachment Method Impacts

The choice of detachment method significantly influences multiple cellular parameters, including viability, surface marker integrity, and functional characteristics. Understanding these quantitative impacts is essential for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific applications.

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Cell Detachment Methods on Cellular Parameters

| Detachment Method | Cell Viability | Detachment Efficiency | Surface Protein Preservation | Recovery Time Required | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | Variable (protocol-dependent) | High (≥90%) [1] | Low (damages most surface proteins) | Immediate use possible | Routine subculturing |

| Accutase | High (gentler than trypsin) [5] | High (comparable to trypsin) | Moderate (compromises specific proteins like FasL/Fas) [5] | ~20 hours for full recovery of affected markers [5] | Flow cytometry (with caution) |

| EDTA-Based | High (mild chemical action) | Low to moderate (may require scraping) [5] | High (best for surface markers) [5] | Minimal | Surface protein analysis |

| Scraping | Moderate (mechanical damage) [5] | High for adherent cells | Highest (preserves all surface proteins) [5] | Immediate use possible | Critical surface marker studies |

| Electrochemical | >90% [4] | 95% [4] | Expected high (non-proteolytic) | Under investigation | Large-scale biomanufacturing |

The data reveal significant trade-offs between detachment efficiency, viability, and phenotype preservation. While enzymatic methods offer efficiency and convenience, they compromise surface protein integrity—a critical consideration for immunophenotyping, receptor studies, and functional assays. EDTA-based approaches better preserve surface markers but may require mechanical assistance for strongly adherent cells. The novel electrochemical method demonstrates exceptional promise with high efficiency and viability while avoiding proteolytic damage, though its comprehensive effects on diverse surface markers require further characterization across cell types [4].

Advanced Research Applications and Implications

Impact on 3D Culture Models and Drug Discovery

The limitations of traditional two-dimensional adherent culture have driven the development of three-dimensional (3D) models that better recapitulate in vivo tissue architecture and functionality. These advanced culture systems present unique challenges and considerations for cell detachment methodologies. 3D cultures demonstrate enhanced physiological relevance compared to 2D monolayers by preserving tissue-specific architecture, supporting critical cell-matrix interactions, and maintaining appropriate expression levels of essential proteins [7] [8]. The transition from 2D to 3D models reveals important scaffold-dependent variability in culture outcomes, as demonstrated in prostate cancer research where different scaffolding materials (Matrigel, GelTrex, and GrowDex) produced significantly different spheroid formation and gene expression patterns, including variations in androgen receptor expression and neuroendocrine marker genes [9].

The detachment of cells from 3D culture systems introduces additional complexity compared to monolayer dissociation. Enzymatic treatments often require longer exposure times and higher concentrations to penetrate matrix materials, potentially increasing damage to cell surface markers and functionality. These challenges have stimulated the development of specialized dissociation protocols for 3D cultures, often incorporating combination approaches using collagenases, dispase, and other matrix-specific enzymes alongside traditional trypsin or Accutase. The preservation of cell viability and phenotype during dissociation from 3D environments remains a significant technical hurdle, particularly for sensitive primary cells and stem cells, driving ongoing research into gentler, more specific detachment strategies [9] [7].

Automation and Artificial Intelligence in Cell Culture

Recent technological advances have introduced automation and artificial intelligence to address issues of consistency and efficiency in adherent cell culture workflows. Traditional visual assessment of cell morphology and confluency introduces substantial inter-operator variability, leading to inconsistencies in subculturing timing and experimental outcomes [10]. Automated monitoring systems like the Olympus Provi CM20 incubation monitoring system utilize AI technology to quantitatively measure culture health parameters including confluency and cell counts using consistent analysis parameters, eliminating subjective assessment and improving reproducibility [10].

These automated systems provide significant advantages for detachment timing decisions by continuously monitoring multiple points in culture vessels and detecting subtle changes in cell morphology and density that might precede morphological deterioration. By establishing standardized parameters for subculturing based on quantitative metrics rather than subjective assessment, automated systems reduce variability in experimental results and improve the reliability of downstream applications including drug screening and functional assays [10]. The integration of such automated assessment with novel detachment technologies like the electrochemical approach represents the future direction of adherent cell culture, enabling closed-system, minimally variable workflows from culture expansion to harvest.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Adherent Cell Culture and Detachment

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-EDTA | Proteolytic enzyme + calcium chelator | Dissociates adherent cells by cleaving adhesion proteins | Requires serum neutralization; monitor incubation time carefully [1] |

| Accutase | Proteolytic, collagenolytic, and DNase activities | Gentle cell detachment and single-cell suspension preparation | Does not require neutralization; avoid pre-warming to 37°C [6] |

| TrypLE | Recombinant fungal protease | Animal-origin-free enzymatic dissociation | Consistent performance; suitable for therapeutic applications |

| EDTA Solution | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid | Calcium chelation disrupts integrin-mediated adhesion | Mild method; may require mechanical assistance for strongly adherent cells [5] |

| DPBS (without Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺) | Balanced salt solution | Washing step to remove serum and ions prior to dissociation | Essential pre-treatment to prevent enzyme inhibition [1] |

| Complete Growth Medium | Basal medium + serum/growth factors | Neutralizes enzymatic activity and provides nutrients | Required after trypsinization; not needed for Accutase [1] [6] |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane matrix | 3D culture substrate mimicking extracellular matrix | Promotes consistent spheroid formation; variable between batches [9] |

| GrowDex | Plant-derived nanofibrillar cellulose | Bioincompatible 3D scaffold for cell culture | Sustainable alternative to animal-derived matrices [9] |

| Anti-adherence Solution | Polymer coating | Prevents cell attachment for spheroid formation | Enables spheroid generation in standard plates at reduced cost [8] |

Future Directions in Adherent Cell Detachment Research

The field of adherent cell detachment is evolving toward methods that better preserve cellular integrity while improving scalability and reproducibility. Several promising directions are emerging from current research:

Electrochemically Enabled Biomanufacturing: The development of enzyme-free electrochemical detachment platforms represents a paradigm shift with potential to transform large-scale biomanufacturing [4]. By applying low-frequency alternating voltage to conductive biocompatible surfaces, this approach achieves high detachment efficiency (>95%) while maintaining excellent viability (>90%) and eliminating concerns associated with animal-derived enzymes [4]. The technology offers particular promise for automated, closed-loop cell culture systems in therapeutic manufacturing, especially for sensitive cell types like primary immune cells for CAR-T therapies where phenotype preservation is critical.

Advanced Biomimetic Surfaces: Research continues into smart culture surfaces with dynamically tunable properties that can be switched from adhesive to non-adhesive states through external stimuli including light, temperature, or electrical signals. These platforms would enable controlled cell release without enzymatic or mechanical stress, potentially revolutionizing both research-scale and industrial-scale culture processes.

Integration with AI-Driven Culture Management: The combination of automated monitoring systems with advanced detachment technologies creates opportunities for fully optimized culture workflows [10]. AI algorithms can precisely determine optimal detachment timing based on quantitative metrics rather than subjective assessment, then trigger appropriate detachment protocols tailored to specific cell types and applications, significantly improving consistency and efficiency across research and manufacturing environments.

These advancing methodologies collectively address the core challenges in adherent cell detachment—balancing efficiency with phenotype preservation, scaling processes while maintaining viability, and standardizing protocols for reproducibility—paving the way for more reliable and physiologically relevant cell-based research and therapies.

The Role of the Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and Adhesion Proteins in Cell Attachment

The Extracellular Matrix (ECM) is a dynamic, three-dimensional network of macromolecules that provides not only structural support to tissues but also critical biochemical and mechanical cues that regulate cellular behavior including adhesion, migration, differentiation, and signal transduction [11]. For adherent cells, the ECM serves as the physical scaffold for attachment, a process mediated primarily by specialized transmembrane receptors, most notably integrins [12]. The interaction between cells and the ECM is not a passive anchoring event but a complex, bidirectional signaling process essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis. Understanding these mechanisms is foundational to the field of adherent cell detachment research, which aims to develop techniques for harvesting cells with minimal damage to their functional and metabolic activity for applications in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and industrial cell manufacturing [13].

This technical guide will detail the core components of the ECM, the fundamental mechanisms of cell adhesion, and the experimental methodologies used to study these interactions. The content is framed within the context of advancing adherent cell detachment research, a field that must balance the need for efficient cell release with the imperative to preserve cell viability, function, and surface protein integrity [13].

Core Components of the Extracellular Matrix

The ECM's composition is highly variable across tissues, but its core structural and functional molecules can be categorized as follows:

Major Structural Proteins

- Collagens: The most abundant proteins in the human body, collagens are fibrous proteins with a unique triple-helix structure that provide tensile strength and structural integrity to tissues. Multiple types exist (e.g., I, II, III, IV), each with specialized functions and tissue distributions [14] [11].

- Elastin: A highly elastic protein that allows tissues such as skin, lungs, and blood vessels to stretch and recoil. It forms cross-linked networks that provide functional resilience and flexibility, working in concert with collagen to determine tissue mechanical properties [14] [11].

Specialized Glycoproteins and Polysaccharides

- Fibronectin: A high-molecular-weight glycoprotein that plays a crucial role in cell adhesion and migration. It contains specific domains, such as the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence, which are recognized by cell surface integrins [11] [15].

- Laminin: A key component of the basement membrane, laminin is essential for forming networks that support cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [15].

- Proteoglycans (PGs) and Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs): PGs are glycosylated proteins characterized by covalently attached GAG chains. GAGs are long, linear polysaccharides with repeating disaccharide units (e.g., heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, keratan sulfate, hyaluronan) [14]. These molecules serve as dynamic regulators of tissue mechanics, modulate cellular responses to mechanical stimuli, and interact with growth factors and cell surface receptors [14]. Key PGs include syndecans, glypicans, and perlecans.

Table 1: Major ECM Components and Their Primary Functions

| ECM Component | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Collagens | Provides tensile strength and structural integrity. | Triple-helix structure; most abundant protein in the body. |

| Elastin | Confers elasticity and recoil to tissues. | Hydrophobic amino acids (Gly, Ala); cross-linked networks. |

| Fibronectin | Mediates cell adhesion and migration. | Contains RGD integrin-binding motif. |

| Laminin | Basement membrane foundation; cell adhesion. | Forms sheet-like networks; crucial for epithelial cells. |

| Proteoglycans/GAGs | Regulates hydration, tissue mechanics, and signaling. | Highly negative charge; interacts with growth factors. |

The physical properties of the ECM—including its stiffness, viscoelasticity, and topology—are not passive traits but active regulators of cell behavior. For instance, ECM stiffness can influence cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation, with dysregulation implicated in diseases like cancer and fibrosis [11]. The stiffness of healthy tissues can range from <2 kPa in the brain to 40–55 MPa in bone, while pathological states like breast cancer tumors can exhibit a significant stiffening (e.g., ~4 kPa vs. 0.167 kPa in normal tissue) [11].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Cell Adhesion

Cell adhesion to the ECM is a multi-step process orchestrated by a complex machinery of transmembrane receptors, intracellular adaptors, and the cytoskeleton.

Integrins: The Primary Transmembrane Receptors

Integrins are the principal cell surface receptors that mediate adhesion to the ECM. They are α/β heterodimeric transmembrane proteins, with 18 α and 8 β subunits forming 24 distinct integrins in mammals [12]. They bind to specific motifs in ECM proteins:

- RGD-binding integrins (e.g., αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1) recognize the Arg-Gly-Asp sequence found in fibronectin, vitronectin, and other proteins [12] [15].

- Collagen-binding integrins (e.g., α1β1, α2β1) recognize the GFOGER motif in collagens [12].

- Laminin-binding integrins (e.g., α3β1, α6β1, α6β4) bind to laminins in the basement membrane [12].

Integrin-mediated adhesion is a dynamic and regulated process. Integrins exist in inactive (bent) and active (extended) conformations. The switch to an active state, which increases affinity for ECM ligands, can be triggered by intracellular signals (inside-out signaling). Upon ligand binding, integrins cluster and initiate outside-in signaling, recruiting a plethora of cytoplasmic proteins to form adhesion plaques [12] [16].

Focal Adhesions and the Adhesome

The linkage of integrins to the actin cytoskeleton is facilitated by a multi-protein complex known as the adhesome, which assembles into focal adhesions (FAs) [16]. Key adaptor and signaling proteins include:

- Talin: Binds directly to the cytoplasmic tail of β-integrins, activating them and recruiting other proteins like vinculin [16].

- Vinculin: Strengthens the integrin-cytoskeleton linkage by simultaneously binding to talin and actin [16].

- Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK): A critical non-receptor tyrosine kinase that transduces integrin-mediated signals, regulating cell spreading, migration, and survival [17] [15].

- Paxillin: An adaptor protein that recruits numerous signaling and structural molecules to focal adhesions [18] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanotransduction pathway from the ECM to the cytoskeleton and nucleus:

Diagram 1: Core ECM-integrin mechanotransduction pathway

Other Adhesion Structures

While integrins are central to cell-ECM adhesion, cells also form other specialized junctions:

- Adherens Junctions: Mediate cell-cell adhesion through cadherin receptors, which are linked to the actin cytoskeleton via catenins (β-catenin, α-catenin) [17].

- Tight Junctions: Form impermeable seals between cells, regulating paracellular transport and maintaining cell polarity. Key components include claudin and occludin [17].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Cell Adhesion

Microcontact Printing and Patterned Substrates

Objective: To engineer defined areas of ECM proteins to study how spatially confined ECM ligands regulate cell adhesion initiation and strength [18].

Detailed Protocol:

- Fabrication of PDMS Stamps: A silicon mold with circular holes of defined diameters (e.g., 2 μm to 10 μm) is used to cast poly(dimethyl)siloxane (PDMS) micropillar stamps [18].

- Inking: The PDMS micropillars are "inked" with a solution of fluorescently labeled ECM protein (e.g., collagen I or fibronectin) [18].

- Printing: The inked stamp is brought into physical contact with a glass coverslip, transferring the protein onto the glass in a defined pattern [18].

- Passivation: The non-patterned glass surface is passivated with bovine serum albumin (BSA) or a non-integrin-binding protein fragment (e.g., FNIII7-10ΔRGD) to prevent non-specific cell attachment [18].

- Cell Seeding and Analysis: Cells are seeded onto the patterned substrate. Adhesion is assessed via confocal microscopy (e.g., staining for actin and paxillin) or functional adhesion assays [18].

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS)

Objective: To quantify the initiation and strength of cell adhesion at high temporal and force resolution [18].

Detailed Protocol:

- Cantilever Functionalization: An atomic force microscopy (AFM) microcantilever is coated with concanavalin A (ConA) to facilitate cell attachment [18].

- Cell Capture: A single, rounded cell is attached to the ConA-coated cantilever [18].

- Adhesion Initiation: The cell is positioned above a specific ECM pattern (created via microcontact printing) and brought into contact for a defined period (e.g., 5 to 360 seconds) to allow adhesion formation and strengthening [18].

- Force Quantification: The cantilever is retracted, and the force required to detach the cell from the substrate is measured. This provides a direct quantification of adhesion force and energy [18].

The following diagram visualizes this integrated experimental workflow:

Diagram 2: Microcontact printing and SCFS workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cell Adhesion and Detachment Research

| Research Reagent | Function and Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-EDTA | Enzymatic cell detachment; trypsin cleaves ECM proteins, EDTA chelates calcium. | Standard, robust method for harvesting adherent cells from culture vessels [13]. |

| Collagenase | Enzyme that specifically degrades native collagen fibrils in the ECM. | Isolation of cells from tissues rich in collagen, such as bone or tendon. |

| Cilengitide | Cyclic RGD peptide; selective inhibitor of αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins. | Studying integrin function and reversing Cell Adhesion-Mediated Drug Resistance (CAMDR) [15]. |

| FNIII7-10ΔRGD | A fibronectin fragment lacking the integrin-binding RGD domain. | Used as a passivation agent to block non-specific cell adhesion on substrates [18]. |

| Anti-Integrin Antibodies | Block specific integrin subtypes to study their function or activate signaling. | Functional studies to dissect the role of specific integrin heterodimers in adhesion. |

| Recombinant ECM Proteins (Fibronectin, Laminin, Vitronectin) | Coat culture surfaces to study cell adhesion on specific ECM components. | Investigating CAMDR or creating defined microenvironments for cell culture [15]. |

Implications for Adherent Cell Detachment Research

The fundamental understanding of cell adhesion directly informs the challenges and opportunities in adherent cell detachment research. The primary goal is to disrupt the very adhesion mechanisms described above while preserving cell health and function [13].

- Enzymatic Detachment: The most common method uses proteolytic enzymes like trypsin to cleave ECM proteins and cell surface receptors. While effective and robust, it can damage critical cell surface proteins, boost apoptotic rates, and dysregulate protein expression, which is undesirable for therapeutic applications [13].

- Non-Enzymatic Detachment:

- Chelating Agents (e.g., EDTA): Bind calcium ions, disrupting calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecules like cadherins. They are less damaging than enzymes but may not be effective for all cell types and can introduce toxicity [13].

- Physical Methods: Scraping, thermal changes, or application of magnetic/electric fields. These are simple and avoid chemical residues but can be difficult to scale and control precisely [13].

- Stimuli-Responsive Surfaces: Advanced materials like thermo-responsive polymers change their properties (e.g., become hydrophilic/hydrophobic) with temperature shifts, allowing controlled cell release without enzymes. Challenges include cost, robustness, and the need for precise control over material characteristics [13].

A critical application is in bioreactor-based cell manufacturing using microcarriers. Developing robust, scalable detachment methods for these systems, such as microcarriers with stimuli-responsive coatings, is a rapidly growing area of research to meet the demands of the expanding cell manufacturing industry [13].

Furthermore, ECM adhesion has been directly linked to Cell Adhesion-Mediated Drug Resistance (CAMDR), a phenomenon where adhesion to ECM proteins like laminin, vitronectin, and fibronectin confers resistance to chemotherapeutic agents in cancer cells, including glioblastoma. This resistance is mediated through integrin αv and the FAK/paxillin/AKT signaling pathway, which suppresses p53-mediated apoptosis [15]. This underscores the therapeutic relevance of understanding and modulating cell-ECM interactions.

Table 3: Common Cell Detachment Methods and Their Characteristics

| Detachment Method | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-EDTA | Proteolysis + Calcium Chelation | Highly effective, robust, low cost. | Damages cell surface proteins; can dysregulate metabolism [13]. |

| Collagenase | Degrades Collagen | Specific for collagen-rich matrices. | Limited to specific ECM contexts; potential for residual enzyme activity. |

| Chelate-Free Buffers | Ionic Disruption of Adhesion | Simpler formulation; no enzyme residuals. | May be less effective for strongly adherent cells [13]. |

| Thermo-Responsive Polymers | Temperature-induced surface hydration change | Non-enzymatic; allows harvest of intact cell sheets. | Requires precise material control; less robust; more expensive [13]. |

| Mechanical Scraping | Physical Shearing Force | Simple; no chemicals or enzymes. | Causes significant cell damage and death; not scalable [13]. |

Cell Detachment as a Critical Step in Subculturing and Cell Harvesting

Cell detachment is a fundamental laboratory procedure essential for the subculturing (passaging) of adherent cells and for harvesting cells for downstream experiments and applications. Adherent cell cultures are characterized by their need to attach to a solid, growth-promoting substrate to proliferate, a property known as "anchorage dependence" [1]. The process of detaching these cells from their culture surface is therefore a critical step that can significantly impact cell health, viability, and the reliability of subsequent experimental data. In the broader context of adherent cell detachment research, the central challenge lies in efficiently breaking the bonds between the cell and its substrate while minimizing damage to delicate cell membranes and functionally important surface proteins [13]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the principles, methods, and quantitative analyses of cell detachment, framed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Cell Adhesion and Detachment

The Biological Basis of Cell Adhesion

Understanding detachment first requires an understanding of how cells adhere. Cell adhesion to a substrate occurs primarily through interactions with the extracellular matrix (ECM), a three-dimensional network of proteins, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans that serves as the foundational scaffold [13]. The key cell-matrix adhesion structures include:

- Focal Adhesions: These are specific sites on the cell membrane where transmembrane proteins called integrins cluster to form a mechanical link between the ECM outside the cell and the actin cytoskeleton inside the cell [13].

- Hemidesmosomes: These junctions provide stable adhesion by connecting intermediate filaments of the cytoskeleton to the ECM, particularly in epithelial cells [13].

The adhesion process is biphasic. The initial phase (within seconds to minutes of contact) is dominated by non-specific, rapid electrostatic interactions. The mature phase (developing over hours to days) is characterized by the formation of specific, protein-mediated bonds, such as those in focal adhesions, which are orders of magnitude stronger [19].

Theoretical Framework of Detachment Forces

The physical process of detaching a cell can be analyzed through the lens of cell mechanics. Research dedicated to comparing cell-cell detachment forces in different experimental setups—such as pipette-pipette, plate-plate, and plate-pipette assays—reveals that the measured detachment force is not an intrinsic property of the cell alone but a global property of the entire system [20] [21] [22].

Theoretical models based on Young-Laplace equations describe cell shape under an applied external force. In a pipette-pipette setup, for instance, the force ((F)) required to detach two identical adherent cells is given by: [ F{dc} = \frac{1}{2} \pi \gamma rH \cos^2 \thetac ] where (\gamma) is the cell surface tension, (rH) is the radius of curvature related to the cell's internal pressure, and (\theta_c) is the cell-cell contact angle determined by the adhesion energy [20] [21]. This model highlights that the measured detachment force depends not only on cell-specific parameters (adhesion tension, surface tension) but also on experimental setup parameters (e.g., pipette radius and pressure) [20] [21].

The following diagram illustrates the key interactions and forces at play during the adhesion and detachment processes.

Established Cell Detachment Methods: A Technical Comparison

A wide array of techniques has been developed to detach adherent cells, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. These can be broadly categorized into chemical and physical methods.

Chemical and Enzymatic Methods

Enzymatic Methods: These involve the use of proteases to cleave the proteins that facilitate cell adhesion.

- Trypsin: This protease is the most common enzymatic method, often used in combination with the chelating agent EDTA. It cleaves peptides after lysine or arginine residues, effectively degrading adhesion proteins and the ECM [1] [13]. Its drawbacks include potential damage to cell surface receptors, which can alter cell phenotype and function [13].

- Accutase: This is a blend of proteolytic and collagenolytic enzymes, widely considered a milder alternative to trypsin. However, recent studies show that it can compromise specific surface proteins, such as Fas ligands (FasL) and Fas receptors, cleaving them into fragments and significantly reducing their surface levels as measured by flow cytometry. This effect is reversible, but requires up to 20 hours for protein recovery [5].

- Collagenase: This enzyme specifically targets collagen, a major ECM component, and is often used for tissues or cell types with a dense collagenous matrix [13].

Non-Enzymatic Chemical Methods:

- Chelating Agents (e.g., EDTA, EGTA): These agents bind to calcium ions ((Ca^{2+})) and, to a lesser extent, magnesium ions ((Mg^{2+})), which are essential for the function of cell adhesion molecules like cadherins and integrins. By removing these ions, chelators weaken cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions [1] [13]. While gentle, EDTA alone is often insufficient for strongly adherent cells and may require mechanical assistance, such as scraping [5].

Physical and Emerging Methods

Mechanical Detachment: This includes physical scraping or pipetting to dislodge cells. While simple and cost-effective, these methods can cause significant cell damage and rupture, leading to low viability and are not suitable for sensitive applications [5] [13].

Novel Electrochemical Method (MIT Approach): A recent innovation involves using a low-frequency alternating current on a conductive biocompatible polymer surface. This method disrupts the cell-surface interface electrochemically without enzymes. It reports detachment efficiency of 95% with cell viability exceeding 90%, offering a promising path for automation and large-scale biomanufacturing by reducing waste and avoiding animal-derived enzymes [4] [23].

Other Physical Stimuli: Research is also exploring light-, magnetic-, and ultrasound-based methods to induce cell detachment in a controlled manner, though these are less established [13].

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the most common detachment methods.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Common Cell Detachment Methods

| Detachment Method | Typical Incubation Time | Reported Cell Viability | Key Advantages | Key Limitations/Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-EDTA [1] [13] | ~2-10 min | >90% (if optimized) | Fast, effective, low-cost, robust | Cleaves surface receptors (e.g., CD4, CD8); can induce apoptosis |

| Accutase [5] | 10 min - 1 h | High (exact % not specified) | Considered milder than trypsin | Compromises FasL & Fas; requires 20h recovery |

| Chelators (e.g., EDTA) [5] [13] | ~20-30 min | High | Gentle on surface proteins; non-enzymatic | Often ineffective for strongly adherent cells alone |

| Mechanical Scraping [5] | N/A | Can be low | Simple, no chemicals | High physical stress, can tear cells, low viability |

| Electrochemical (MIT) [4] [23] | "Within minutes" | >90% | Enzyme-free, high viability, automatable | Emerging technology, requires specialized surfaces |

Standardized and Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Passaging Adherent Mammalian Cells

The following is a detailed protocol for subculturing adherent cells using enzymatic dissociation, as derived from standard laboratory practice [1].

- Assessment: Before passaging, monitor cells to ensure they are in the log phase of growth and have a viability greater than 90%. Do not allow cells to become over-confluent.

- Media Removal: Aspirate and discard the spent cell culture media from the culture vessel.

- Washing: Gently wash the cell layer with a balanced salt solution without calcium and magnesium (e.g., PBS). Use approximately 2 mL per 10 cm² of surface area. This step removes residual serum, which contains trypsin inhibitors.

- Dissociation Reagent Application: Add a pre-warmed dissociation reagent (e.g., trypsin, TrypLE) to the side of the vessel. Use enough to cover the cell layer (approx. 0.5 mL per 10 cm²). Gently rock the vessel to ensure complete coverage.

- Incubation: Incubate the vessel at room temperature for approximately 2 minutes. The exact time varies by cell line.

- Monitoring: Observe cells under a microscope. If less than 90% of cells are detached, increase incubation time in 30-second increments, tapping the vessel gently to expedite detachment.

- Neutralization: When most cells are detached, add a volume of pre-warmed complete growth medium equivalent to at least twice the volume of the dissociation reagent used. Pipette the medium over the cell layer surface to disperse the cells and neutralize the enzyme.

- Centrifugation: Transfer the cell suspension to a centrifuge tube and pellet the cells at 200 x g for 5–10 minutes.

- Resuspension and Seeding: Resuspend the cell pellet in fresh, pre-warmed complete growth medium. Count the cells using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter, then dilute the suspension to the recommended seeding density and pipette into new culture vessels.

The workflow for this standard protocol, as well as for the novel electrochemical method, is summarized in the following diagram.

Experimental Analysis of Detachment Effects on Surface Proteins

Objective: To evaluate the impact of different detachment agents on the surface expression of Fas Ligand (FasL) and Fas receptor on macrophages (e.g., RAW264.7 cells) using flow cytometry [5].

Materials:

- Adherent macrophage cell line.

- Detachment solutions: Accutase, EDTA-based non-enzymatic solution (e.g., Versene).

- Complete growth medium.

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Antibodies for flow cytometry: Anti-FasL, Anti-Fas, and an isotype control.

- Flow cytometer.

Method:

- Cell Culture: Grow cells to approximately 80% confluency.

- Detachment: For each experimental group, perform the following:

- Aspirate media and wash with PBS.

- Add the recommended volume of Accutase or EDTA-based solution.

- Incubate for 10 minutes or 30 minutes at room temperature.

- For a control group, detach cells using a cell scraper.

- Neutralization and Collection: Neutralize enzymatic action with complete medium. Gently pipette to collect cells. Avoid vigorous pipetting.

- Cell Processing: Centrifuge cells, wash with PBS, and resuspend in FACS buffer.

- Staining: Aliquot cells and incubate with fluorescently-labeled antibodies against FasL and Fas (and appropriate isotype controls) for 30-60 minutes on ice or in the dark.

- Analysis: Wash cells to remove unbound antibody, resuspend in FACS buffer, and analyze on a flow cytometer. Compare the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of FasL and Fas between the Accutase-treated and EDTA-treated groups.

Expected Results: Cells detached with Accutase will show a significant decrease (p < 0.001) in the MFI of surface FasL and Fas compared to cells detached with the EDTA-based solution or by scraping, indicating cleavage of these specific surface proteins [5].

Quantitative Data and Research Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cell Detachment

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-EDTA [1] [13] | Proteolytic enzyme cleaves adhesion proteins; EDTA chelates Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺. | Concentration and incubation time must be optimized per cell line to minimize surface protein damage. |

| Accutase [5] | Blend of enzymes for gentle dissociation. | Not universally "gentle"; can cleave specific proteins like FasL. Requires recovery time for surface protein re-expression. |

| Non-Enzymatic Dissociation Buffer (e.g., Versene) [5] | Chelates Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ to disrupt integrin-mediated adhesion. | Ideal for preserving surface antigens for flow cytometry, but may be ineffective for some strongly adherent cells. |

| TrypLE [1] | A recombinant fungal trypsin-like enzyme. | A non-animal-derived alternative to trypsin, offering consistent performance and reduced risk of contamination. |

| Chelate-Free Solutions [13] | Often use cationic salts to disrupt electrostatic interactions. | Simple and avoid chelators, but may be less effective and require optimization for each application. |

| Collagenase [13] | Degrades native collagen in the ECM. | Essential for dissociating tissues or cells embedded in a collagen-rich matrix. |

Quantitative Analysis of Adhesion Strength

Single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) and FluidFM technology allow for the precise measurement of cell detachment forces across different stages of adhesion. A comparative study highlights the dramatic increase in adhesion strength over time [19].

Table 3: Quantified Detachment Forces and Energies in Early vs. Mature Adhesion

| Adhesion Phase | Contact Time | Maximum Detachment Force (MDF) | Detachment Energy | Dominant Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Adhesion [19] | 5 - 30 seconds | 0.5 - 4 nN | 1 - 40 fJ (femtojoules) | Non-specific electrostatic forces |

| Mature Adhesion [19] | 1 - 3 days | ~600 nN | ~10 pJ (picojoules) | Specific, protein-mediated bonds (e.g., integrin-ECM) |

This data demonstrates that adhesion forces can increase by approximately 150-fold as the contact matures from initial, non-specific attachment to the formation of specific focal adhesions [19]. This has critical implications for detachment protocols, as mature cultures require much harsher conditions to harvest, which inherently increases the risk of cellular damage.

Cell detachment is a critical, yet complex, step that bridges routine cell culture and downstream applications. The choice of detachment method is a significant variable that directly influences cell viability, phenotype, surface protein integrity, and consequently, experimental outcomes. While enzymatic methods like trypsin are robust and widely used, evidence of their detrimental effects on cells is growing [5] [13]. Non-enzymatic chemical methods are gentler but may lack efficiency.

The future of adherent cell detachment research is moving towards precise, controllable, and non-invasive technologies. The emergence of novel approaches, such as the electrochemical platform from MIT, points to a promising direction for automating biomanufacturing workflows for cell therapies and tissue engineering, reducing waste, and improving reproducibility [4] [23]. Furthermore, the development of smart biomaterials, such as microcarriers with stimuli-responsive coatings that release cells upon application of a specific trigger (temperature, light, pH), is a rapidly advancing field aimed at solving the scalability challenges in industrial cell manufacturing [13]. As the demand for high-quality cells in research and therapy continues to grow, the development and adoption of advanced, gentle detachment strategies will remain a central focus in biomedical science.

The process of adherent cell detachment is a fundamental yet critical procedure in biomedical research, industrial biomanufacturing, and therapeutic development. Adherent cells require physical attachment to solid surfaces for survival, growth, and reproduction, making detachment an essential step for cell passaging, harvesting for experiments, and production of cell-based therapies [4]. However, this necessary process inherently challenges cell integrity, creating a delicate balance between efficient cell release and preservation of cellular health. The transition from an attached to suspended state represents a period of significant cellular stress, potentially triggering adverse responses ranging from compromised viability to initiation of programmed cell death pathways [13].

Understanding the impact of detachment techniques on cell health is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to generate reliable, reproducible data and develop effective cellular products. Traditional enzymatic methods, while effective for detachment, can induce profound stresses through damage to delicate cell membranes and surface proteins, particularly in sensitive primary cells [4]. Even milder dissociation agents previously considered gentle can compromise specific surface markers and require substantial recovery periods, thereby influencing experimental outcomes [5]. As the field advances toward more sophisticated applications in regenerative medicine, cell therapy, and large-scale biomanufacturing, the development and selection of detachment strategies that minimize detrimental impacts on cell health have become increasingly crucial [4] [13].

Core Mechanisms: How Detachment Methods Influence Cellular Fate

Molecular Interactions During Detachment

Cell adhesion to surfaces occurs through complex molecular interactions involving integrins, cadherins, and other adhesion receptors that connect the extracellular matrix (ECM) to the intracellular cytoskeleton [13]. These adhesion complexes not only provide physical attachment but also mediate critical survival signals. Disruption of these connections, which is the fundamental goal of cell detachment, inevitably interferes with these signaling pathways. The method of disruption directly influences the cellular response, determining whether cells remain viable and functional or enter states of stress, senescence, or apoptosis [13].

The extracellular matrix (ECM) forms a 3D fibrous network of proteins, proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and metalloproteinases that serves as the foundation for cell attachment [13]. Cell-matrix adhesion occurs primarily through specialized structures such as focal adhesions, which involve integrin proteins that transmit both mechanical and chemical signals across the cell membrane. During detachment, the method used to disrupt these connections varies significantly:

- Enzymatic methods (e.g., trypsin, accutase) cleave specific peptide bonds in adhesion proteins [5] [13]

- Chelating agents (e.g., EDTA) remove divalent cations like calcium that are essential for integrin function [5] [13]

- Physical methods (e.g., bubbling, scraping) apply mechanical forces to break adhesions [4] [24]

- Stimuli-responsive surfaces (e.g., electrochemical, thermal) modify surface properties to reduce adhesion strength [4] [13]

Detachment-Induced Signaling Pathways

The disruption of adhesion complexes during detachment initiates intracellular signaling cascades that can ultimately influence cell fate. The diagram below illustrates key pathways through which detachment methods impact cell health, particularly through anoikis (a form of apoptosis triggered by detachment from the ECM) and membrane integrity damage.

The relationship between detachment mechanisms and cellular outcomes reveals that different approaches trigger distinct stress pathways. Enzymatic methods primarily cause surface protein damage, which can directly initiate apoptosis, while methods that disrupt adhesion complexes often trigger anoikis. Physical approaches like scraping may more directly compromise membrane integrity, leading to immediate viability loss [5] [13].

Comparative Analysis of Detachment Techniques and Their Impacts

Enzymatic Detachment Methods

Enzymatic approaches represent the most widely used detachment strategy in research and industrial applications. Trypsin, a protease that cleaves after lysine or arginine residues, effectively degrades most cell surface proteins and extracellular matrix components but causes significant damage to cell membranes and surface markers [4] [13]. This damage can extend beyond immediate viability reduction to longer-term effects including dysregulation of protein expression, enhanced apoptotic cell death, and altered metabolic pathways [13].

Accutase, often considered a milder enzymatic alternative, demonstrates reduced impact on many surface markers but shows specific vulnerability for certain proteins. Research has revealed that accutase significantly decreases surface levels of Fas ligands (FasL) and Fas receptors, cleaving the extracellular portion of FasL into fragments under 20 kD in size [5]. This specific protein damage required approximately 20 hours for recovery after accutase treatment, during which surface levels of these proteins gradually returned to normal [5]. Despite this specific damage, accutase demonstrated superior performance in maintaining overall cell viability compared to EDTA-based solutions or PBS buffers, particularly with extended exposure times up to 90 minutes [5].

Non-Enzymatic and Novel Detachment Strategies

Non-enzymatic methods offer alternatives that avoid proteolytic damage to cell surfaces. Chelating agents like EDTA function by removing calcium ions essential for integrin-mediated adhesion, providing a mild detachment approach but often requiring mechanical assistance for strongly adherent cells [5] [13]. Mechanical scraping, while effective, frequently causes membrane damage and cell tearing, reducing overall viability and increasing cellular debris [5].

Recent innovations have introduced advanced detachment strategies seeking to overcome limitations of traditional methods. MIT researchers have developed an electrochemical approach using alternating current on a conductive biocompatible polymer nanocomposite surface [4]. This method disrupts adhesion within minutes while maintaining over 90% cell viability, addressing key limitations of enzymatic and mechanical methods [4]. Another novel system utilizes electrochemically generated bubbles to create shear stress at the cell-surface interface, effectively removing cells without generating harmful bleach byproducts that can damage sensitive cells [24]. This technique has proven effective across multiple cell types, including algae, ovarian cancer cells, and bone cells, demonstrating its broad applicability [24].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Cell Detachment Methods

| Method | Detachment Efficiency | Cell Viability | Impact on Surface Proteins | Recovery Time Required | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | High (≈95%) [13] | Moderate (varies by cell type) [13] | Severe damage [4] [13] | 4-24 hours [13] | High [13] |

| Accutase | High (≈90%) [5] | High (>90%) [5] | Selective damage (e.g., FasL, Fas) [5] | ~20 hours [5] | Moderate [5] |

| EDTA | Low to Moderate [5] | High [5] | Minimal [5] | Minimal [5] | Low [13] |

| Scraping | High [5] | Low to Moderate [5] [25] | Physical damage [5] | Variable [5] | Low [13] |

| Electrochemical | High (95%) [4] | High (>90%) [4] | Minimal reported [4] | Minimal reported [4] | High [4] [24] |

Assessing Detachment Impacts: Viability and Apoptosis Methodologies

Technical Protocols for Cell Health Assessment

Accurately evaluating the impact of detachment methods on cell health requires robust assessment techniques. The following experimental protocols provide methodologies for quantifying cell viability and apoptosis following detachment procedures.

Modified EB/AO Apoptosis Assay in 96-Well Format

The Ethidium Bromide/Acridine Orange (EB/AO) staining method enables simultaneous quantification of live, apoptotic, and necrotic cell populations, making it particularly valuable for assessing detachment impacts [25]. This modified approach eliminates detaching and washing steps for adherent cells, minimizing additional damage and preserving fragile cell populations.

Materials and Equipment:

- Cell culture with appropriate detachment agent

- Ethidium bromide solution (100 μg/mL)

- Acridine orange solution (100 μg/mL)

- 96-well plate (preferably glass-bottom for optimal optical clarity)

- Centrifuge with 96-well plate carriers

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filters

Experimental Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Following detachment by the test method, transfer cell suspension to 96-well plate (≈10,000-50,000 cells per well).

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge plate at 300×g for 5 minutes to sediment all cells, including floaters, to the well bottom.

- Staining: Add EB/AO working solution (1:1 mixture of EB and AO) directly to wells without removing supernatant.

- Incubation: Incubate for 5-10 minutes at room temperature protected from light.

- Immediate Analysis: Visualize using fluorescence microscope without washing steps:

- Live cells: Normal green nucleus with organized structure

- Early apoptotic: Bright green nucleus with condensed or fragmented chromatin

- Late apoptotic: Condensed and fragmented orange chromatin

- Necrotic: Structurally normal orange nucleus [25]

This method's advantage lies in its ability to maintain adherent cells in their cultured state, avoiding additional detachment stress that could alter apoptotic population distributions [25].

Annexin V/Propidium Iodide Flow Cytometry Protocol

The Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) binding assay represents another widely used approach for detecting apoptosis and viability following cell detachment.

Materials and Equipment:

- Detached cell suspension

- Annexin V binding buffer (containing calcium ions)

- Fluorescently-labeled Annexin V probe

- Propidium iodide (PI) solution

- Flow cytometry staining buffer

- Benchtop centrifuge

- Flow cytometer

Experimental Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Detach cells using test method and transfer 1×10⁶ cells per condition to microcentrifuge tubes.

- Washing: Pellet cells by centrifugation (300×g, 5 minutes), resuspend in Annexin binding buffer.

- Staining: Add fluorescent Annexin V probe, incubate 15 minutes at room temperature protected from light.

- Viability Staining: Add PI (final concentration 0.5-1.0 μg/mL) and incubate 5-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Analysis: Analyze by flow cytometry without additional washing:

- Annexin V⁻/PI⁻: Viable, non-apoptotic cells

- Annexin V⁺/PI⁻: Early apoptotic cells

- Annexin V⁺/PI⁺: Late apoptotic or necrotic cells [26]

Critical Considerations:

- Avoid chelating agents (EDTA, EGTA) in buffers as Annexin V requires calcium for phospholipid binding [26]

- Include controls: unstained, single stains, and apoptosis-induced positive control

- Process samples immediately after detachment for accurate assessment

Experimental Workflow for Detachment Method Comparison

The comprehensive evaluation of detachment methods requires a systematic approach comparing multiple cell health parameters. The following diagram illustrates an integrated workflow for assessing detachment impacts from initial processing through final analysis.

This comprehensive workflow enables researchers to systematically evaluate how different detachment methods affect immediate cell health, recovery trajectory, and long-term functionality. The time-course analysis is particularly important, as some surface protein damage requires extended recovery periods up to 20 hours [5].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Detachment and Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Function & Mechanism | Key Applications | Considerations & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-EDTA | Proteolytic enzyme cleaves adhesion proteins; EDTA chelates calcium [13] | Routine cell culture, robust cell lines [13] | Damages surface proteins, requires serum inhibition [4] [13] |

| Accutase | Enzyme mixture with proteolytic and collagenolytic activity [5] | Sensitive cells, flow cytometry [5] [27] | Cleaves specific markers (FasL, Fas); requires recovery time [5] |

| Non-Enzymatic Dissociation Buffers | Chelate calcium/magnesium ions to disrupt cadherins and integrins [5] [13] | Surface marker preservation, sensitive applications [5] | Less effective for strongly adherent cells [5] |

| Annexin V Binding Buffers | Provide calcium-enriched environment for phosphatidylserine binding [26] | Apoptosis detection post-detachment [26] | Incompatible with EDTA; requires immediate analysis [26] |

| Viability Dyes (PI, EB, AO) | DNA intercalating agents distinguish membrane integrity [25] [26] | Viability assessment, apoptosis staging [25] | Varying specificity; requires appropriate controls [25] |

| Electrochemical Systems | Alternating current disrupts adhesion; bubble generation creates shear [4] [24] | High-value cells, automation-compatible processes [4] | Specialized equipment required; optimization needed [4] |

The impact of cell detachment on cellular health represents a critical consideration in experimental design and therapeutic development. Traditional enzymatic methods, while effective for cell release, impose significant stresses through surface protein damage, membrane disruption, and induction of apoptotic pathways [4] [5] [13]. The emerging recognition that even "gentle" enzymatic methods like accutase cause specific protein damage requiring extended recovery periods underscores the necessity of carefully matching detachment strategies to experimental goals [5].

Future directions in detachment research focus on developing enzyme-free systems that minimize cellular damage while enabling automation and scalability. Electrochemical approaches achieving over 90% viability and 95% detachment efficiency demonstrate the potential for integrated systems that maintain cell health throughout culture processes [4] [24]. As the cell dissociation market progresses—projected to grow from USD 455.03 million in 2025 to USD 1621.47 million by 2035—increased investment in innovative technologies addressing these challenges is anticipated [28]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate detachment methods and assessment protocols remains fundamental to generating reliable data and developing effective cellular therapies where preservation of cellular integrity is paramount.

A Guide to Cell Detachment Methods: From Classic Enzymatic to Novel Technologies

The culture of adherent cells is a cornerstone of biomedical research, drug development, and cell therapy. These cells require physical attachment to a solid surface to survive, grow, and reproduce [4]. A critical, yet challenging, step in working with these cells is the process of detachment and dissociation—releasing them from the culture surface while maintaining cellular integrity and function. Enzymatic dissociation remains one of the most robust and frequently used methods for harvesting adherent cells [13]. These methods function by selectively breaking down the proteins that facilitate cell adhesion to the culture substrate and the connections between adjacent cells.

The importance of choosing an appropriate detachment method cannot be overstated. Traditional techniques, while effective, can compromise cell viability by damaging delicate cell membranes and degrading crucial surface proteins, which in turn can alter cellular function and skew experimental results [29] [4] [13]. This is particularly critical for applications in regenerative medicine and cell therapy, where the preservation of cell health and function is paramount. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of four key enzymatic agents—Trypsin, TrypLE, Accutase, and Collagenase—detailing their mechanisms, optimal use cases, and practical protocols to inform the work of researchers and drug development professionals.

Enzyme Mechanisms and Characteristics

Enzymatic detachment agents work by cleaving specific proteins involved in cell adhesion. The extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell-surface proteins like cadherins and integrins mediate the strong attachment of cells to the culture surface; these proteins often require calcium ions to maintain their adhesive function [30] [13]. Enzymes disrupt this adhesion through proteolytic activity.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and primary applications of each enzyme.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Enzymatic Cell Dissociation Agents

| Enzyme | Mechanism of Action | Key Characteristics | Primary Cell Type Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | Cleaves peptide bonds after lysine or arginine residues; often used with EDTA to chelate calcium [29] [30] [13]. | Robust, cost-effective; can damage many surface proteins and boost apoptotic cell death [29] [13]. | Strongly adherent cell lines; high-density cultures (with collagenase) [30]. |

| TrypLE | A recombinant fungal protease with trypsin-like activity, cleaving after lysine and arginine [30]. | Animal-origin-free, consistent; gentler on cells than trypsin; direct protocol substitute for trypsin [30] [31]. | Strongly adherent cells; applications requiring animal-origin-free reagents [30]. |

| Accutase | A blend of collagenolytic and proteolytic enzymes, including trypsin-like protease XIV and thermolysin [29] [32]. | Ready-to-use, gentle; preserves cell surface antigens and viability; effective for delicate cells [29] [32]. | Pluripotent stem cells, neuronal cells, macrophages, and other sensitive primary cells [29] [32]. |

| Collagenase | Targets and degrades native collagen, a major component of the ECM and some tissues [30]. | Essential for breaking down structural collagen; often used in combination with other enzymes [30]. | Primary tissues rich in collagen; compact tissues [30]. |

Impact on Cell Surface Proteins and Recovery

A critical consideration when selecting a dissociation enzyme is its effect on cell surface markers. Research has demonstrated that even enzymes marketed as "gentle" can have significant, though often reversible, impacts.

A 2022 study revealed that Accutase can significantly decrease the surface levels of Fas ligands (FasL) and Fas receptors on macrophages compared to EDTA-based non-enzymatic detachment. The enzyme was found to cleave the extracellular region of FasL into small fragments. Fortunately, this effect was not permanent; the surface expression of these proteins required up to 20 hours to fully recover after accutase treatment. Notably, the surface levels of other markers, like F4/80 on murine macrophages, were not altered, indicating the effect is protein-specific [29].

This underscores the importance of allowing adequate recovery time after cell detachment and before proceeding with experiments where surface marker integrity is crucial, such as flow cytometry or functional immune assays.

Quantitative Data and Comparison

To aid in evidence-based reagent selection, the following table synthesizes quantitative data on enzyme performance from the literature.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Detachment Enzymes

| Enzyme | Typical Concentration | Incubation Time (at 37°C) | Reported Cell Viability | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | 0.25% (for tissue) [30] | 5-15 min (cells) [30]; 20-30 min (after cold incubation for tissue) [30] | >90% (standard protocol) [30] | Can dysregulate protein expression and enhance oncogene expression [13]. |

| TrypLE | Volume to cover monolayer (e.g., 5 mL/75 cm²) [30] | Until detachment observed [30] | >90% (standard protocol) [30] | 91% detachment efficiency of LNCaP cells from a specialized surface within 10 minutes [31]. |

| Accutase | Ready-to-use solution [32] | 10 min to 1 hour [29] | >90% [32] | Maintained significantly higher cell viability after 60 and 90 min treatment vs. EDTA [29]. Compromises surface FasL/Fas; requires 20h recovery [29]. |

| Collagenase | 50-200 U/mL [30] | 4-18 hours [30] | Varies by tissue and time | Effective for disaggregating whole tissue; often used with other enzymes like Dispase [30]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Below are standardized protocols for the enzymatic dissociation of adherent cell monolayers and primary tissues. Always perform these procedures under sterile conditions.

General Enzymatic Dissociation for Adherent Cell Monolayers

This procedure is a template for Trypsin, TrypLE, and Accutase. Optimal conditions should be determined empirically for each cell line [30].

- Aspiration: Remove and discard the spent cell culture media from the flask or dish.

- Rinse: Wash the cell monolayer using a balanced salt solution without calcium and magnesium (e.g., DPBS). Add the wash solution to the side of the vessel opposite the cells, rock gently for 1-2 minutes, and aspirate the solution. This step removes residual calcium and serum that would inhibit the enzyme.

- Enzyme Application: Add the pre-warmed dissociation solution to the vessel, ensuring complete coverage of the cell monolayer. Use approximately 2-3 mL per 25 cm² of surface area [30].

- Incubation: Incubate the vessel at 37°C. Rock the flask gently periodically. Monitor the cells under an inverted microscope. Most cells detach within 5-15 minutes, but this can vary.

- Neutralization: When cells are completely detached, add complete growth medium (containing serum) to the flask. For serum-free workflows, use an inhibitor like soybean trypsin inhibitor (note: not recommended for TrypLE [30]). Gently pipette the suspension to disperse any clumps.

- Centrifugation: Transfer the cell suspension to a conical tube and centrifuge at approximately 100-200 × g for 5-10 minutes.

- Resuspension: Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in fresh, pre-warmed complete medium.

- Counting and Seeding: Determine viable cell density and percent viability using an automated cell counter or hemocytometer. Seed, incubate, and subculture according to your specific protocol [30].

Primary Tissue Dissociation Protocols

Trypsin-Based Tissue Disaggregation

This method is effective for many tissues but requires careful timing [30].

- Mincing: After dissection, mince the tissue into 3-4 mm pieces with sterile instruments.

- Washing: Wash the tissue pieces several times in a balanced salt solution without calcium and magnesium, allowing pieces to settle between washes.

- Cold Penetration: Place the container on ice, remove supernatant, and add 0.25% trypsin solution (1 mL per 100 mg tissue). Incubate at 4°C for 6-18 hours to allow enzyme penetration.

- Enzyme Activation: Decant and discard the trypsin. Incubate the tissue pieces with the residual trypsin at 37°C for 20-30 minutes.

- Dispersion: Add warm complete media and disperse the tissue by gentle pipetting. For serum-free media, add a soybean trypsin inhibitor.

- Filtration and Seeding: Filter the cell suspension through a sterile 100-200 µm mesh, count cells, and seed for culture [30].

Collagenase-Based Tissue Disaggregation

Ideal for tissues rich in structural collagen, such as connective tissues [30].

- Mincing and Washing: Mince tissue into 3-4 mm pieces and wash several times with HBSS containing calcium and magnesium.

- Enzyme Application: Submerge the tissue in HBSS with calcium and magnesium and add collagenase to a final concentration of 50-200 U/mL. Supplementing with 3 mM CaCl₂ can increase efficiency.

- Digestion: Incubate at 37°C for 4-18 hours on a rocker platform.

- Dispersion and Washing: Disperse the cells by passing through a sterile mesh. Wash the dispersed cells several times by centrifugation in HBSS without collagenase.

- Seeding: Resuspend the final cell pellet in culture medium, determine viable cell density, and seed the cells [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Enzymatic Cell Dissociation Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| DPBS (without Ca2+/Mg2+) | A balanced salt solution used to rinse the cell monolayer prior to dissociation, removing inhibitory divalent cations and serum [30]. |

| Trypsin-EDTA | A classic, potent enzymatic cocktail for detaching strongly adherent cell lines. EDTA chelates calcium, weakening integrin-mediated adhesion [30] [13]. |

| TrypLE Express | A recombinant, animal-origin-free enzyme that functions as a direct substitute for trypsin in existing protocols, offering greater consistency and gentler action [30]. |

| Accutase | A gentle, ready-to-use blended enzyme solution ideal for dissociating sensitive cells like stem cells and neurons while preserving surface markers [29] [32]. |

| Cell Dissociation Buffer | A non-enzymatic, EDTA-based solution used for lightly adherent cells or when the integrity of all surface proteins is critical [30]. |

| Soybean Trypsin Inhibitor | Used to quench trypsin activity after cell detachment in serum-free cell culture workflows [30]. |

| Complete Growth Medium | Used to neutralize enzymatic activity after detachment (via serum) and to resuspend the cell pellet for counting and seeding [30]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Mechanisms

Enzymatic Cell Detachment Mechanism

This diagram illustrates the general mechanism by which enzymatic and non-enzymatic agents facilitate cell detachment.

Standardized Cell Detachment Experimental Workflow

This flowchart outlines the key steps in a general enzymatic cell detachment protocol.

Enzymatic methods using Trypsin, TrypLE, Accutase, and Collagenase provide a powerful and versatile toolkit for harvesting adherent cells. The choice of enzyme is a critical experimental parameter that balances detachment efficiency against the preservation of cell viability, surface markers, and functionality. While enzymatic methods are currently the most robust, they are not without their limitations, including the potential degradation of surface proteins and the introduction of animal-derived components [4] [13].

The field of adherent cell detachment research is actively evolving to address these challenges. Future directions focus on developing non-enzymatic, stimuli-responsive strategies that offer greater precision and reduce cellular damage. Promising approaches include:

- Electrochemical Detachment: Novel platforms using alternating electrochemical current on conductive polymer surfaces can disrupt adhesion within minutes while maintaining over 90% cell viability, presenting a potential pathway for automated biomanufacturing [4].

- Advanced Microfluidic Systems: Sensor-based microfluidic extraction systems can detect a cell's "pre-detachment moment" by monitoring its oscillatory response to hydrodynamic forces. This allows for dynamic adjustment of suction parameters, enabling gentle, non-invasive extraction of single cells with minimal stress [33].

- Smart Microcarriers: For large-scale bioreactor cultures, the development of microcarriers with stimuli-responsive coatings (e.g., thermoresponsive polymers) allows for cell harvesting without enzymes, which is crucial for the expanding cell manufacturing industry [13].

As research progresses, the integration of these advanced, controlled detachment technologies will be essential for improving the reproducibility, scalability, and quality of cells used in therapeutic applications and sophisticated in vitro models.