Antibiotic Efficacy Against Mycoplasma pneumoniae: From Macrolide Resistance to Novel Therapeutic Strategies

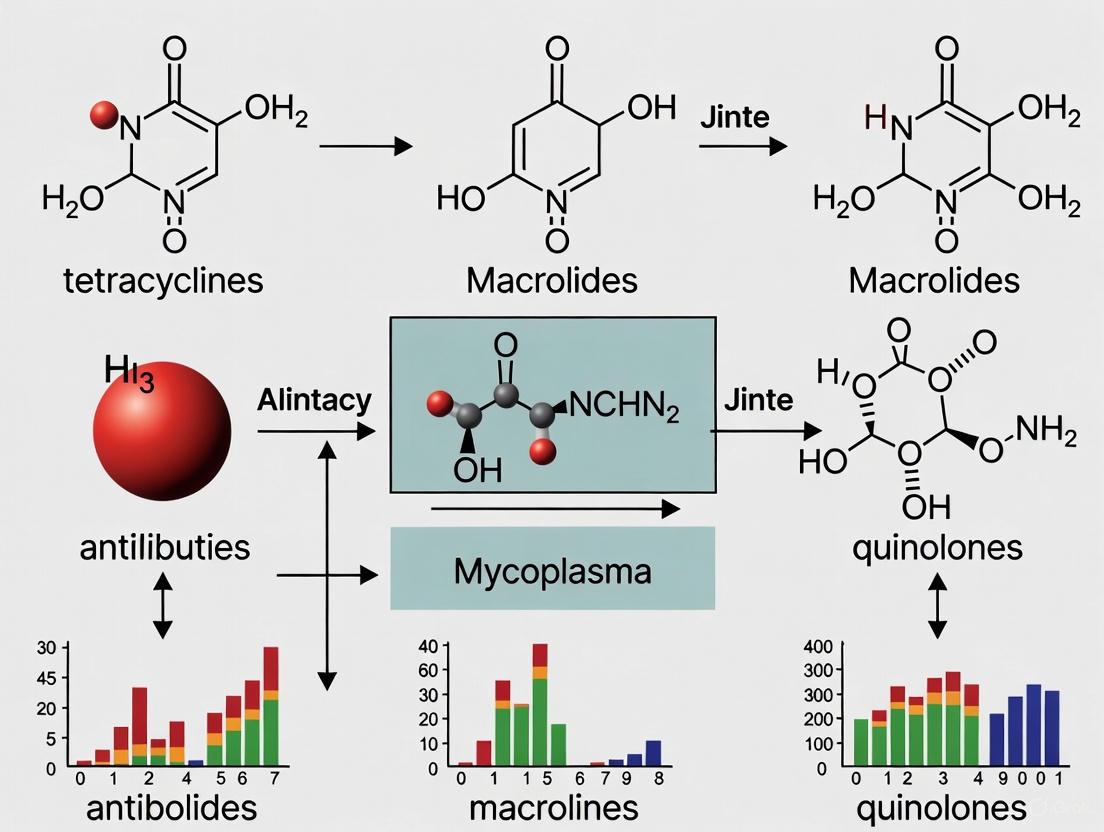

This article synthesizes current research on the efficacy of various antibiotics for eradicating Mycoplasma pneumoniae, with a particular focus on the global challenge of macrolide resistance.

Antibiotic Efficacy Against Mycoplasma pneumoniae: From Macrolide Resistance to Novel Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the efficacy of various antibiotics for eradicating Mycoplasma pneumoniae, with a particular focus on the global challenge of macrolide resistance. It explores foundational mechanisms of antibiotic action and bacterial evasion, evaluates methodological approaches for assessing efficacy in both planktonic and biofilm states, and investigates troubleshooting strategies such as synergistic antibiotic combinations and alternative non-antibiotic modalities. The content further provides a comparative validation of clinical outcomes across different patient populations and antibiotic classes, including macrolides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review aims to bridge laboratory findings with clinical applications to guide the development of next-generation therapeutic interventions.

Understanding Mycoplasma pneumoniae and the Challenge of Antibiotic Resistance

Mycoplasma pneumoniae stands as a remarkable exception in the bacterial world, representing one of the smallest self-replicating organisms known to science. This pathogen lacks a cell wall—a defining feature of most bacteria—possessing only a triple-layered cell membrane enriched with sterols [1] [2]. This minimalist cellular architecture stems from extensive genomic reduction; its genome spans approximately 816 kilobase pairs containing around 687 genes, reflecting an evolutionary trajectory toward obligate parasitism in the human respiratory tract [1]. This genomic reduction has rendered M. pneumoniae intrinsically resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics that target peptidoglycan synthesis, necessitating alternative therapeutic strategies that inhibit protein synthesis or DNA replication [1] [2].

The clinical significance of M. pneumoniae has been highlighted by its recent global resurgence following the relaxation of COVID-19 pandemic control measures. After a prolonged period of suppression during 2020-2022, outbreaks emerged worldwide in 2023-2024, causing substantial morbidity in both pediatric and adult populations [3] [4]. This resurgence has provided new insights into the epidemiology of this pathogen and renewed focus on the challenges it presents, particularly the growing prevalence of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP) strains, especially in East Asia where resistance rates exceed 80% [5] [2]. Understanding the unique biology of this wall-less pathogen is thus essential for developing effective countermeasures against infections that range from mild respiratory illness to severe pneumonia requiring hospitalization.

Unique Structural Biology and Pathogenic Mechanisms

The Terminal Organelle: Adhesion and Motility Apparatus

The absence of a cell wall has profound implications for the cellular organization of M. pneumoniae. Instead of rigid peptidoglycan-based structure, this pathogen relies on a sophisticated internal cytoskeleton to maintain structural integrity and facilitate essential pathogenic functions. Central to its virulence is a specialized polar extension known as the terminal organelle (or attachment organelle), which orchestrates both cytoadherence to host epithelia and a unique form of gliding motility [1].

The terminal organelle features a complex bipartite architecture with surface-exposed nap-like proteins that facilitate host-pathogen interactions, and an intricately organized internal structure that generates mechanical force [1]. The adhesion machinery comprises four evolutionarily conserved surface proteins: P1 (MPN141), P90/P40 (encoded by MPN142 as proteolytic cleavage products), and P30 (MPN453). Spatial mapping demonstrates that the P1 adhesin complex, comprising P1 and P90/P40 subunits, localizes at the apical tip forming a rigid membrane anchor, while P30 dynamically associates with the complex periphery to regulate force transduction during gliding motility [1].

Internally, the terminal organelle contains an electron-dense core structure maintained through three specialized components: the terminal button, paired plates, and bowl complex. This core scaffold provides mechanical stability and serves as an assembly platform for the adhesion machinery [1]. The coordinated action of these structures enables M. pneumoniae to adhere to respiratory epithelium, propelling itself via gliding motility to colonize host tissues while evading mucociliary clearance [6].

Cytotoxicity and Immune Evasion Strategies

The pathogenic strategy of M. pneumoniae extends beyond adhesion to active host cell damage and immune system manipulation. Upon attachment to respiratory epithelium, the bacterium releases several cytotoxic molecules, including hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and community-acquired respiratory distress syndrome (CARDS) toxin [1] [2]. These virulence factors work in concert to damage epithelial cells and cilia, disrupting mucociliary clearance and promoting the characteristic tissue damage observed in mycoplasma pneumonia.

The interaction between respiratory epithelial cells and surface lipoproteins of M. pneumoniae stimulates the host immune system through Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 or TLR-4 pathways, potentially inducing intercellular adhesion molecule receptor synthesis [2]. However, the pathogen employs several immune evasion strategies, including antigenic variation of surface proteins and the formation of biofilm towers that provide enhanced resistance to both antibiotics and host immune effectors [7]. Biofilm formation represents a particularly important adaptation for chronic infection, as these structures show dramatically increased resistance to erythromycin (up to 8,500-128,000 times the minimal inhibitory concentration for planktonic cells) and complement-mediated killing [7].

Antibiotic Efficacy Comparison: Clinical and Experimental Data

Treatment Modalities and Outcomes in Pediatric Pneumonia

The absence of a cell wall in M. pneumoniae fundamentally shapes therapeutic approaches, restricting effective antibiotic classes to those targeting protein synthesis (macrolides, tetracyclines) or DNA replication (fluoroquinolones). The rising prevalence of macrolide-resistant strains has complicated treatment decisions, particularly for pediatric patients where tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones have historically been used with caution due to potential side effects.

A comprehensive 2025 study of 389 children with M. pneumoniae pneumonia (MPP) in South Korea revealed striking patterns in treatment efficacy across different therapeutic approaches. The overall macrolide resistance rate was 89.1%, yet treatment outcomes varied significantly between intervention strategies [5]. The table below summarizes the fever duration and clinical outcomes across different treatment modalities.

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of Treatment Modalities for Pediatric M. pneumoniae Pneumonia

| Treatment Group | Number of Patients | Total Fever Duration (Days, Median) | Time to Defervescence After Treatment Initiation (Days) | Hospitalization Rate | Macrolide Resistance Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Resolution (SR) | 85 | 5.0 | N/A | 81.4% | Not reported |

| Macrolide Only (ML) | 70 | 7.0 | 2-3 | 84.7% | 72.0% |

| Macrolide with Other Treatments (ML-O) | 148 | 8.0 | 2-3 | 93.9% | 96.7% |

| Second-line Antibiotics and/or Steroids (2nd-A/S) | 86 | 7.0 | 0-2 | 84.7% | 100% |

This real-world data reveals several important patterns. First, a substantial proportion of cases (21.9%) experienced spontaneous resolution without targeted antibiotic therapy, highlighting the self-limiting nature of many M. pneumoniae infections [5]. Second, despite high macrolide resistance rates, macrolide monotherapy remained effective in many patients, with fever resolution occurring within 2-3 days of treatment initiation. Third, the combination of macrolides with other treatments was associated with longer total fever duration and higher hospitalization rates, likely reflecting treatment selection bias for more severe cases [5].

Doxycycline Efficacy in Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia

For severe or macrolide-unresponsive infections, second-line antibiotics become essential. A 2025 clinical analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of doxycycline in treating Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia (SMPP) in children under eight years old, comparing outcomes between a doxycycline treatment group (44 cases) and a macrolide control group (48 cases) [8]. All included children had failed to respond to at least three days of prior macrolide therapy, meeting criteria for macrolide-unresponsive Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia (MUMPP).

Table 2: Doxycycline vs. Macrolide Efficacy in Severe Pediatric M. pneumoniae Pneumonia

| Clinical Parameter | Doxycycline Group (n=44) | Macrolide Group (n=48) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cough Relief Time (Days) | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.6 | < 0.05 |

| Pulmonary Rale Resolution Time (Days) | 6.2 ± 1.3 | 8.0 ± 1.7 | < 0.05 |

| Overall Treatment Efficacy Rate | 88.6% | 75.0% | < 0.05 |

| Fever Resolution Time | No significant difference | No significant difference | > 0.05 |

| Hospitalization Duration | No significant difference | No significant difference | > 0.05 |

| Adverse Event Rate | 18.2% | 16.7% | > 0.05 |

The study demonstrated that doxycycline provided significantly faster resolution of key respiratory symptoms compared to continued macrolide therapy, with comparable safety profiles [8]. Notably, no tooth discoloration—a historical concern with tetracycline use in children—was observed in this cohort, supporting recent guidelines that recognize the favorable risk-benefit profile of short-course doxycycline for resistant M. pneumoniae infections in children [8].

Synergistic Antibiotic Combinations Against Biofilm Structures

The formation of biofilm towers by M. pneumoniae represents a significant challenge for antimicrobial therapy, as these structures confer dramatically increased antibiotic resistance. A 2025 investigation explored eradication strategies for these resilient bacterial communities, testing individual antibiotics and combination therapies against pre-formed biofilm structures [7].

Table 3: Antibiotic Efficacy Against M. pneumoniae Biofilm Towers

| Antibiotic/Combination | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for Planktonic Cells | Efficacy Against Biofilm Towers | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythromycin (Macrolide) | Reference MIC | 8,500-128,000× less effective (high resistance) | Inhibits protein synthesis |

| Doxycycline (Tetracycline) | Comparable to erythromycin for planktonic cells | Moderate efficacy as monotherapy | Inhibits protein synthesis |

| Moxifloxacin (Fluoroquinolone) | Comparable to erythromycin for planktonic cells | Moderate efficacy as monotherapy | Inhibits DNA replication |

| Erythromycin + Doxycycline | N/A | Synergistic effect (FICI* < 0.5) | Dual protein synthesis inhibition |

| Erythromycin + Moxifloxacin | N/A | Synergistic effect (FICI* < 0.5) | Protein synthesis + DNA replication inhibition |

| Doxycycline + Moxifloxacin | N/A | Synergistic effect (FICI* < 0.5) | Protein synthesis + DNA replication inhibition |

*FICI: Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index

Checkerboard assays revealed that dual combinations of erythromycin, moxifloxacin, and doxycycline acted synergistically against two strains of M. pneumoniae [7]. Although fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines in children are not preferred over macrolides due to potential side effects, this work demonstrates that synergistic interactions among therapeutic agents provide potential clinical paths to substantially reducing or eradicating M. pneumoniae biofilms, thereby decreasing morbidity [7].

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Checkerboard Assay for Synergistic Antibiotic Interactions

The evaluation of antibiotic combinations against M. pneumoniae follows standardized methodologies that enable quantification of synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effects. The checkerboard broth microdilution assay represents a crucial experimental approach for identifying effective combinations against resistant strains or biofilm structures [7].

Protocol:

- Antibiotic Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of test antibiotics (erythromycin, doxycycline, moxifloxacin) at specified concentrations. Erythromycin stock at 25.6 mg/ml in ethanol; moxifloxacin stock at 2.048 mg/ml in ultra-pure water; doxycycline stock at 20 mg/ml in ultra-pure water [7].

- Bacterial Inoculum: Syringe M. pneumoniae stocks through a 26-g needle multiple times, followed by dilution in SP-4 broth to achieve a final inoculum of 1.0 × 10⁴ CFU/ml for antibiotic testing [7].

- Checkerboard Setup: Dilute antibiotics to start with twice the MIC of each antibiotic. Add decreasing concentrations of both antibiotics to each well of a 96-well plate, except for the last row and column containing only one antibiotic [7].

- Inoculation and Incubation: Inoculate M. pneumoniae in all wells and incubate at 37°C until the growth control changes color from red to yellow in SP-4 medium [7].

- FICI Calculation: Determine the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index using the formula: FICI = (MIC of drug A in combination/MIC of drug A alone) + (MIC of drug B in combination/MIC of drug B alone). Synergy is defined as FICI ≤ 0.5 [7].

Biofilm Tower Eradication Assay

The evaluation of antimicrobial agents against M. pneumoniae biofilm structures requires specialized methodologies that account for the unique properties of these organized bacterial communities.

Protocol:

- Biofilm Formation: Grow M. pneumoniae wild-type strains M129 and 19294 in SP-4 broth in 24- or 96-well plates at 37°C for extended periods (several days) to allow distinct mound- or dome-shaped biofilm towers to form [7].

- Antimicrobial Exposure: Expose pre-formed biofilm towers to individual antibiotics or combinations at clinically relevant concentrations. Include H₂O₂ as a model for small molecule therapeutics [7].

- Crystal Violet Staining: Perform crystal violet assays to quantify remaining biofilm biomass after treatment. This provides a quantitative measure of biofilm eradication [7].

- Microscopic Validation: Validate crystal violet results using scanning electron microscopy to visually confirm the eradication of biofilm towers, which often reveals more complete clearance than indicated by staining alone [7].

- Viability Assessment: Combine antibiotic treatments with complementary killing mechanisms (e.g., erythromycin with complement) to assess complete eradication of viable bacteria within biofilm structures [7].

Macrolide Resistance Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

The growing challenge of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP) demands thorough understanding of its underlying mechanisms and clinical consequences. Resistance primarily occurs through point mutations in domain V of the 23S rRNA gene, with nucleotide transitions A2063G and A2064G being most common [2]. These alterations structurally modify the macrolide binding site on the 50S ribosomal subunit, reducing drug affinity and rendering conventional treatments ineffective.

The geographic distribution of MRMP shows striking variation, with resistance rates exceeding 80% in East Asian countries like South Korea, China, and Japan, compared to less than 10% in North America and Europe [2]. This disparity likely reflects regional differences in antibiotic prescribing practices and the clonal expansion of resistant strains, particularly sequence type 3 strains that dominate in high-resistance regions [2].

Despite high-level in vitro resistance, the clinical picture is more nuanced. Many children with MRMP infections experience spontaneous resolution without targeted antibiotic therapy, and macrolide treatment often provides symptomatic benefit even when infections involve resistant strains [5] [2]. This apparent paradox may reflect the immunomodulatory properties of macrolides, their activity against co-pathogens, or the self-limiting nature of many M. pneumoniae infections.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for M. pneumoniae Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SP-4 Broth Medium | Complex undefined medium containing peptone, yeast extract, serum components | Primary culture medium for axenic growth | Supports biofilm tower formation; color change indicates metabolic activity |

| Cell Culture Systems | BEAS-2B respiratory epithelial cells | Host-pathogen interaction studies | Enables investigation of adhesion, cytotoxicity, and biofilm formation on living cells |

| PCR Reagents | Primers targeting P1 adhesin gene, 23S rRNA resistance mutations | Detection, quantification, and resistance profiling | Enables differentiation of macrolide-resistant and sensitive strains |

| Antibiotic Stock Solutions | Erythromycin (25.6 mg/ml in ethanol), Doxycycline (20 mg/ml in water), Moxifloxacin (2.048 mg/ml in water) | Antimicrobial efficacy testing | Vehicle controls essential for ethanol-soluble compounds |

| Biofilm Assessment Tools | Crystal violet stain, Scanning electron microscopy equipment | Biofilm formation and eradication quantification | SEM provides superior visualization of biofilm architecture compared to light microscopy |

| Animal Models | Syrian hamsters, mouse pulmonary infection models | In vivo pathogenesis and therapeutic studies | Limited models due to species specificity of human-pathogenic M. pneumoniae |

The unique wall-less biology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae continues to present formidable challenges for clinical management and therapeutic development. The recent global resurgence following the COVID-19 pandemic hiatus has underscored the persistent public health threat posed by this pathogen, while the inexorable spread of macrolide-resistant strains demands innovative treatment approaches [3] [4].

Promising avenues for future investigation include the development of combination therapies that exploit synergistic antibiotic interactions to overcome biofilm-mediated resistance [7]. Additionally, targeting the adhesion and motility apparatus represents an attractive strategy that could prevent initial colonization and interrupt disease progression [1] [6]. As our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying M. pneumoniae pathogenesis continues to deepen, particularly the function of the terminal organelle and its role in immune evasion, new opportunities for therapeutic intervention will undoubtedly emerge.

The self-limiting nature of many M. pneumoniae infections, coupled with the growing challenge of antibiotic resistance, suggests that future management strategies may increasingly focus on immunomodulatory approaches rather than purely antimicrobial interventions. Nevertheless, the continued evolution of this minimalist pathogen ensures that it will remain a significant subject of clinical concern and scientific fascination for years to come.

Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MRMP) has emerged as a significant global public health challenge, particularly in the management of community-acquired pneumonia. The epidemiology of MRMP demonstrates stark geographical variations, with notably high resistance rates in East Asia compared to Western nations. This phenomenon is primarily driven by point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, which reduce macrolide binding affinity and compromise treatment efficacy. The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily disrupted transmission dynamics through non-pharmaceutical interventions, but recent surveillance data indicate a pronounced post-pandemic resurgence of M. pneumoniae infections, including macrolide-resistant strains. Understanding these global patterns is essential for developing targeted surveillance, stewardship programs, and treatment guidelines to address this evolving threat.

Global Prevalence and Regional Distribution

The prevalence of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae exhibits dramatic geographical disparities, with the highest burden concentrated in East Asia.

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Macrolide-Resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP)

| World Health Organization Region | MRMP Prevalence (%) | Key Countries/Regions with Reported Data |

|---|---|---|

| Western Pacific | 53.4% | China, Japan, South Korea |

| South East Asia | 9.8% | Limited data available |

| Americas | 8.4% | United States |

| Europe | 5.1% | Southern Italy, France |

Recent studies from specific regions provide more granular data on resistance patterns:

- Southern Italy (2023-2025): A comprehensive study reported an overall MRMP rate of 7.5%, with the highest prevalence observed in preadolescents aged 10-14 years (12.6%). The majority (96%) of resistant strains harbored the A2063G mutation. [10]

- China: Resistance rates remain exceptionally high. A 2025 study from Xi'an reported that 100% of cultured isolates harbored the A2063G mutation in the 23S rRNA gene, with phenotypic resistance to macrolides observed in 38.6% of cases. [11] Earlier multicenter studies in Chinese adults demonstrated resistance rates as high as 80% against erythromycin and 72% against azithromycin. [12]

- Japan (Osaka): Surveillance data from 2024 indicate a resurgence of MRMP following the COVID-19 pandemic, with resistance rates climbing again to 65.2% after a period of decline during peak intervention periods. [13]

Table 2: Recent Regional Surveillance Data on MRMP

| Region | Time Period | Study Population | Resistance Rate | Predominant Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Italy | 2023-2025 | All ages (median: 10 years) | 7.5% | A2063G (96%) |

| Xi'an, China | 2023 | Hospitalized children | 38.6% (phenotypic) | A2063G (100% genotypic) |

| Osaka, Japan | 2024 | Pediatric patients | 65.2% | A2063G |

| Beijing, China | 2011-2017 | Adult patients | 41.7% | A2063G |

Molecular Mechanisms of Macrolide Resistance

The primary mechanism of macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae involves target site modification through point mutations in domain V of the 23S rRNA gene, which codes for the macrolide binding site on the bacterial ribosome.

Key Genetic Mutations

The most prevalent mutations occur at specific positions in the 23S rRNA gene:

- A2063G transition: This is the most common resistance mutation globally, accounting for approximately 96.8% of resistant strains. This mutation confers high-level resistance to 14- and 15-membered macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin) and intermediate resistance to 16-membered macrolides. [14] [9]

- A2064G transition: The second most frequent mutation, representing about 4.8% of cases, also resulting in high-level macrolide resistance. [9]

- Less common mutations: Including A2063C, A2063T, A2067G, and C2617G, which are rarely observed in clinical isolates. [14]

These mutations reduce binding affinity between macrolide antibiotics and the ribosomal target site, preventing inhibition of protein synthesis.

Additional Resistance Mechanisms

While target site mutations represent the primary resistance mechanism, emerging research suggests supplementary pathways:

- Efflux pump mechanisms: A 2025 study from Beijing identified two clinical isolates carrying efflux pump genes (msrA/B and mefA). When exposed to the efflux pump inhibitor reserpine, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for azithromycin decreased to a quarter of the original values, confirming functional contribution to resistance. [15]

- Ribosomal protein mutations: Mutations in genes encoding ribosomal proteins L4 and L22 have been associated with low-level macrolide resistance in laboratory-selected mutants, though these are rarely reported in clinical isolates. [14]

Diagram Title: Molecular Mechanisms of Macrolide Resistance in M. pneumoniae

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Accurate detection of macrolide resistance is crucial for appropriate clinical management and epidemiological surveillance. The following section details standardized laboratory protocols.

Molecular Detection of Resistance Mutations

Protocol: PCR Amplification and Sequencing of 23S rRNA Domain V

- Sample Preparation: Respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or throat swabs) are collected and transported in appropriate medium. Nucleic acids are extracted using commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini kit, STARMag Universal Cartridge kit). [10] [15]

- PCR Amplification: Amplify domain V of the 23S rRNA gene using specific primers. A typical reaction mixture includes DNA template (2-5 µL), PCR reaction mix (40-45 µL), and Taq enzyme (3 µL). Cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 93°C for 2 minutes, followed by 10 cycles of 93°C for 45 seconds, 55°C for 1 minute, then 30 cycles of 93°C for 30 seconds and 55°C for 10 minutes. [12]

- Sequencing and Analysis: PCR products are purified and sequenced using Sanger sequencing. Sequences are aligned with reference strains using software such as BioEdit and MEGA to identify point mutations at positions 2063, 2064, and 2617. [10]

Culture and Phenotypic Susceptibility Testing

Protocol: Broth Microdilution Method for MIC Determination

- Culture Conditions: Inoculate respiratory specimens into PPLO broth medium supplemented with horse serum, yeast extract, and glucose. Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 2-3 weeks, monitoring for color change (red to yellow) indicating growth. Subculture positive samples onto solid PPLO agar for colony isolation. [11]

- MIC Testing: Prepare serial dilutions of antimicrobial agents (erythromycin, azithromycin, tetracycline, fluoroquinolones) in microtiter plates. Inoculate wells with standardized bacterial suspension. Incubate plates at 37°C until growth is visible in control wells (typically 24-48 hours). The MIC is defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that prevents color change. [12] [15]

- Interpretive Criteria: Resistance breakpoints vary by antibiotic: Erythromycin (≥1 µg/mL), Azithromycin (≥1 µg/mL), Tetracycline (≤2 µg/mL), Moxifloxacin (≤0.5 µg/mL). [12]

Diagram Title: MRMP Detection and Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MRMP Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | PPLO Broth, PPLO Agar (Oxoid) | Culture and isolation of M. pneumoniae from clinical specimens; growth indicated by color change with phenol red indicator. [12] [11] |

| Molecular Detection Kits | Allplex Respiratory Panel Assays, PCR Fluorescence Probing Kit (Zhi-Jiang) | Multiplex real-time PCR detection of M. pneumoniae and other respiratory pathogens; includes primer sets for specific target amplification. [10] [12] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), STARMag Universal Cartridge Kit (Seegene) | Extraction of high-quality DNA from clinical samples for downstream molecular applications including PCR and sequencing. [10] [15] |

| Antibiotics for Susceptibility Testing | Erythromycin, Azithromycin, Midecamycin, Tetracycline, Moxifloxacin | Reference standards for determining minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) using broth microdilution methods. [12] [15] |

| Sequencing Reagents | BioEdit, MEGA software, CLC Sequence Viewer | Analysis of sequence data for identification of resistance-conferring mutations in target genes (23S rRNA). [10] [12] |

| Specialized Equipment | MALDI-TOF MS (QuanTOF I), Real-time PCR systems (ABI Prism 7500) | Genotype identification through mass spectrometry; quantitative PCR for pathogen detection and bacterial load determination. [12] [11] |

Treatment Alternatives and Clinical Management

With rising macrolide resistance, particularly in East Asia, alternative treatment strategies have become increasingly important for effective clinical management.

Alternative Antimicrobial Agents

- Tetracyclines: Doxycycline and minocycline demonstrate excellent activity against MRMP with no reported resistance in clinical isolates. These agents are effective alternatives for older children and adults but are typically avoided in young children due to potential effects on bone and tooth development. [12] [14]

- Fluoroquinolones: Moxifloxacin and levofloxacin maintain efficacy against MRMP and serve as valuable alternatives, particularly for adults. However, their use in children is restricted due to concerns about potential effects on cartilage development. Recent surveillance has detected strains with elevated MICs nearing resistance breakpoints, suggesting emerging resistance may become a future concern. [12] [14]

- 16-membered macrolides: Midecamycin, a 16-membered ring macrolide, has shown promising activity against some azithromycin-resistant strains (MIC90: 16 µg/mL) and may represent a treatment option, particularly for pediatric patients where tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are contraindicated. [15]

Adjunctive Therapies

For refractory MRMP pneumonia characterized by excessive immune activation, immunomodulatory agents may be beneficial:

- Corticosteroids: Used to dampen excessive inflammatory response and immune-mediated pulmonary injury in severe cases. [14]

- Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG): May be beneficial in modulating host immune responses in severe, refractory cases. [14]

The selection of alternative agents must consider patient age, severity of illness, local resistance patterns, and potential adverse effects, highlighting the importance of antimicrobial stewardship programs to optimize treatment outcomes while minimizing further resistance development.

The global epidemiology of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae presents a complex and evolving challenge with significant geographical disparities. The high resistance rates in East Asia compared to Western regions underscore the impact of regional antibiotic practices and surveillance systems. The primary mechanism of resistance involves point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, with the A2063G transition mutation dominating globally. Advanced molecular techniques combined with traditional culture methods provide comprehensive tools for detection and characterization. As MRMP infections resurge following the COVID-19 pandemic, continued surveillance, judicious antibiotic use, and consideration of alternative treatment approaches will be essential to mitigate the impact of this resistant pathogen on public health worldwide.

Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance: Mutations in the 23S rRNA Gene (A2063G and A2064G) represents a critical area of investigation within antimicrobial resistance research. These specific point mutations within the peptidyl transferase loop of domain V in the 23S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene constitute the primary mechanism of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae [14]. The rising global prevalence of these mutations, particularly in Asian countries where resistance rates approach 80-90%, directly compromises the clinical efficacy of first-line macrolide antibiotics and presents substantial challenges for managing respiratory infections [14] [16]. This guide systematically compares how these mutations impact mycoplasma removal efficacy across different antibiotic classes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with synthesized experimental data and methodologies essential for advancing therapeutic strategies.

Molecular Basis of 23S rRNA Mutations and Macrolide Resistance

Mechanism of Antibiotic Action and Resistance

Macrolide antibiotics, including erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin, exert their antibacterial effect by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit. This binding occurs specifically within the nascent peptide exit tunnel of the ribosome, adjacent to the peptidyl transferase center [14]. The binding site predominantly involves domain V of the 23S rRNA, where macrolides physically block the elongation of the growing polypeptide chain, thereby inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis and preventing bacterial replication [17].

The acquisition of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae occurs almost exclusively through point mutations that modify this binding site [14]. Unlike many other bacterial pathogens that utilize efflux mechanisms or enzymatic modification of antibiotics, M. pneumoniae resistance is primarily mediated through target site modification via mutations in the 23S rRNA gene [14]. The most prevalent mutations involve single nucleotide transitions at positions A2063G and A2064G (Escherichia coli numbering system) within domain V [18]. These nucleotide substitutions induce conformational changes in the ribosome that reduce macrolide binding affinity through steric hindrance and alteration of critical interaction points [19].

Structural Consequences of Mutations

The molecular mechanisms by which A2063G and A2064G mutations confer resistance have been elucidated through structural and biochemical studies. The A2063G transition introduces a guanine residue that possesses an additional exocyclic 2-amino group compared to the wild-type adenine. This amino group sterically hinders optimal positioning of macrolide molecules within the binding pocket, creating physical interference that disrupts drug-ribosome interactions [19]. Similarly, the A2064G mutation introduces comparable steric constraints, though with somewhat different effects on binding affinity.

Computational modeling based on crystallographic data reveals that these mutations cause significant van der Waals overlaps between the rRNA and the macrolide structure [19]. The A2063G mutation produces more substantial steric hindrance than A2064G, correlating with observed higher levels of resistance for the A2063G mutation [14] [20]. When both mutations occur together (double mutation), they act synergistically to create more profound conformational changes in the ribosomal binding site, resulting in even greater resistance levels compared to either single mutation alone [20].

Figure 1: Mechanism of Macrolide Resistance Due to 23S rRNA Mutations. This diagram illustrates how A2063G/A2064G mutations in the 23S rRNA gene prevent macrolide binding to the ribosomal target site, allowing ongoing protein synthesis in resistant strains.

Global Prevalence and Distribution Patterns

The prevalence of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MRMP) harboring A2063G and A2064G mutations demonstrates significant geographical variation, reflecting regional differences in antibiotic usage practices and surveillance systems.

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae

| Region | Resistance Prevalence (%) | Most Common Mutation | Trend | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia | 62-96.4% | A2063G (77%) | Stable at high levels | [16] [20] [21] |

| United States | 2.4-9% | A2063G (>95%) | Increasing post-pandemic | [21] |

| Europe | 5-6% | A2063G (5%) | Stable at low levels | [16] [21] |

| Iran | 0% in studied cohort | Not detected | Not established | [22] |

Recent surveillance data indicates an alarming reemergence of MRMP following the COVID-19 pandemic. A 2025 study from Ohio, USA, documented a significant increase in cases, with resistance rates rising from 0.7% in June 2024 to 4.4% by September 2024 [21]. This represents a substantial increase compared to the pre-pandemic resistance rate of 2.8% reported in the same pediatric population [21]. Similarly, a 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis encompassing 53 studies and 8,960 individuals confirmed the persistently high resistance rates in Asia (62%) compared to Europe (6%) and America (9%) [16] [20].

The A2063G transition is unequivocally the dominant resistance mechanism worldwide, accounting for approximately 67% of resistant cases globally [16]. The A2064G mutation occurs less frequently, with a global pooled prevalence of only 3% [16]. The concurrent presence of both A2063G and A2064G (double mutation) is relatively rare but clinically significant due to its association with more severe disease manifestations and higher levels of resistance [20].

Comparative Antibiotic Efficacy Against Mutated Strains

Macrolides and Their Limitations

Macrolide antibiotics demonstrate markedly reduced efficacy against M. pneumoniae strains harboring A2063G and A2064G mutations. The resistance mechanism profoundly impacts clinical outcomes, as evidenced by treatment failure, prolonged symptomatology, and extended hospitalization.

Table 2: Antibiotic Efficacy Against Mycoplasma pneumoniae with 23S rRNA Mutations

| Antibiotic Class | Example Agents | Mechanism of Action | Efficacy Against Wild-Type Strains | Efficacy Against A2063G/A2064G Mutants | Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolides | Azithromycin, Clarithromycin, Erythromycin | Binds to 23S rRNA, inhibits protein synthesis | High (First-line treatment) | Severely compromised | Target site modification (A2063G/A2064G) |

| Tetracyclines | Doxycycline, Minocycline | Binds to 30S ribosomal subunit | Moderate (Second-line) | Maintained efficacy | No cross-resistance reported |

| Fluoroquinolones | Levofloxacin | Inhibits DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV | Moderate (Second-line) | Maintained efficacy | No cross-resistance reported |

| Ketolides | Telithromycin | Binds to 23S rRNA with higher affinity | High | Variable, some retained activity | Enhanced ribosomal binding |

Clinical studies directly correlate these mutations with refractory disease courses. Patients infected with MRMP strains experience significantly longer fever duration (HR = 3.72 for all genotypes), extended hospital stays, and increased risk of severe disease progression compared to those with macrolide-sensitive strains [20]. The meta-analysis by Frontiers in Pharmacology (2025) further established that double mutations (A2063G + A2064G) confer more severe clinical outcomes compared to single mutations, including prolonged fever duration (HR = 5.32 versus 3.66) and higher likelihood of severe illness (HR = 7.80 versus 5.89) [20].

Comparative clinical studies between different macrolides have demonstrated variability in treatment outcomes. A 2021 study comparing clarithromycin versus erythromycin for pediatric respiratory mycoplasma infections found superior outcomes with clarithromycin, including higher MP-PCR negative rates (96.23% vs. 75.47%), shorter antipyretic time (2.63 vs. 4.06 days), reduced hospitalization duration (15.14 vs. 20.63 days), and lower incidence of adverse effects [23].

Alternative Antibiotic Classes

For infections with MRMP, tetracyclines (doxycycline, minocycline) and fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin) represent effective alternative therapeutic options as they do not exhibit cross-resistance with macrolides [14]. These antibiotic classes target different bacterial components—tetracyclines bind to the 30S ribosomal subunit while fluoroquinolones inhibit DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV—allowing them to bypass the resistance conferred by 23S rRNA mutations [14].

Importantly, systematic surveillance has not detected acquired resistance to tetracyclines or fluoroquinolones in MRMP clinical isolates, supporting their utility as second-line agents [14]. However, usage limitations exist for these antibiotic classes in pediatric populations due to potential side effects: tetracyclines are typically avoided in children under 8 years due to tooth discoloration risk, while fluoroquinolones have restrictions in growing children due to cartilage development concerns [14].

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Analysis

Molecular Detection of Resistance Mutations

Protocol 1: PCR Amplification and Sequencing of 23S rRNA Domain V

This method represents the gold standard for detecting A2063G and A2064G mutations with high specificity and reliability.

DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from clinical samples (throat swabs or cultured isolates) using commercial kits such as the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche) [22]. Begin with 200μL of sample and elute in 50-100μL of elution buffer.

PCR Amplification: Prepare 25μL reaction mixtures containing:

- 2.5μL 10X PCR buffer

- 1.5μL MgCl₂ (25mM)

- 0.5μL dNTPs (10mM each)

- 0.5μL each forward and reverse primer (10μM)

- 0.2μL Taq DNA polymerase (5U/μL)

- 2μL DNA template

- 17.3μL nuclease-free water

Primer sequences for 23S rRNA domain V:

- Forward: 5'-TAACTATAACGGTCCTAAGG-3'

- Reverse: 5'-GCTACAACTGGAGCATAAGA-3' [22]

Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 4 minutes

- 35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 45 seconds

- Annealing: 55°C for 45 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 50 seconds

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

Product Analysis: Verify amplification by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel; expected product size is 793bp [22].

Sequencing: Purify PCR products using commercial kits and perform Sanger sequencing with the same amplification primers. Analyze sequences using alignment software (e.g., ClustalW2) to identify A2063G and A2064G mutations [22].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Detecting 23S rRNA Mutations. This diagram outlines the key steps in identifying A2063G and A2064G mutations in Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates, from sample collection to final mutation reporting.

Protocol 2: Broth Microdilution for Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination

This phenotypic method quantitatively measures macrolide resistance levels.

Bacterial Inoculum Preparation: Grow M. pneumoniae in PPLO broth medium enriched with horse serum and glucose for 5-7 days until color change indicates adequate growth. Standardize inoculum to 1-5×10⁵ CFU/mL [22].

Antibiotic Preparation: Prepare doubling dilutions of clarithromycin (or other macrolides) in enriched PPLO broth in 96-well microtiter plates. Typical concentration range: 0.000125-512 μg/mL [22].

Inoculation and Incubation: Add standardized bacterial inoculum to each well. Include growth control (no antibiotic) and sterility control (no inoculum) wells. Seal plates and incubate at 37°C for 5-7 days under appropriate atmospheric conditions [22].

MIC Determination: Read plates when color change occurs in growth control well. The MIC is defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that prevents color change (indicating no bacterial growth) [22]. Interpret results according to CLSI breakpoints where available.

Quality Control: Include reference strains with known MIC values (e.g., M. pneumoniae ATCC 29342) with each assay run [22].

Comparative Efficacy Study Design

Protocol 3: Clinical Treatment Response Assessment

This protocol outlines a standardized approach for comparing antibiotic efficacy in clinical settings.

Patient Selection and Grouping: Enroll patients with confirmed M. pneumoniae infection (positive by PCR) and randomize into treatment groups using a random number table. Ensure comparable baseline characteristics between groups (age, gender, illness severity) [23].

Treatment Administration:

Efficacy Evaluation:

Statistical Analysis: Compare outcomes between groups using appropriate statistical tests (chi-square for categorical variables, t-tests for continuous variables) with significance set at p<0.05 [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating 23S rRNA Mutations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche) | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from clinical samples | Efficient removal of PCR inhibitors; suitable for small sample volumes |

| PCR Reagents | Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, specific primers for 23S rRNA domain V | Amplification of target resistance region | High fidelity amplification; optimized for GC-rich regions |

| Culture Media | PPLO broth with horse serum and glucose | Propagation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates | Supports fastidious growth of mycoplasma species |

| Antibiotic Standards | Clarithromycin, azithromycin, erythromycin, doxycycline, levofloxacin | MIC determination and resistance profiling | Pharmaceutical grade; precisely quantified potency |

| Sequencing Reagents | BigDye Terminators, cycle sequencing kits | Mutation detection and confirmation | High accuracy base calling; compatible with automated sequencers |

| Reference Strains | M. pneumoniae ATCC 29342 | Quality control in resistance testing | Genotype and phenotype well-characterized |

| Commercial Detection Kits | PCR-RFLP kits, real-time PCR kits with HRM analysis | Rapid screening for A2063G/A2064G mutations | High-throughput capability; reduced turnaround time |

The A2063G and A2064G mutations in the 23S rRNA gene represent a formidable challenge in the management of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, rendering first-line macrolide antibiotics increasingly ineffective, particularly in regions with high resistance prevalence. The comprehensive analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that these mutations significantly impair mycoplasma removal efficacy of macrolides, necessitating alternative treatment approaches including tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones that maintain activity against resistant strains. Researchers and drug development professionals must prioritize ongoing surveillance of these mutations, development of rapid diagnostic methods for their detection, and investigation of novel antimicrobial agents that circumvent this resistance mechanism. The experimental protocols and comparative data provided herein offer foundational methodologies for advancing these critical research objectives aimed at addressing the expanding challenge of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae.

Biofilm formation represents a fundamental virulence strategy for bacterial pathogens, creating protected communities that exhibit dramatically enhanced antibiotic resistance while simultaneously attenuating virulence factor production to facilitate persistent infections. This review synthesizes current findings on the mechanistic basis of biofilm-mediated resistance, examining the synergistic roles of physical diffusion barriers, metabolic heterogeneity, and persister cell formation. We specifically contextualize these principles within Mycoplasma pneumoniae biofilm research, comparing the efficacy of conventional and novel therapeutic strategies. Quantitative analysis reveals that biofilms can increase antibiotic minimum inhibitory concentrations by several orders of magnitude compared to planktonic cells, presenting formidable challenges for clinical management. Emerging anti-virulence approaches that target quorum sensing systems and biofilm dispersion mechanisms offer promising alternatives to traditional bactericidal strategies, potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance development while effectively disrupting pathogenic communities.

Bacterial biofilms are immobile, three-dimensional aggregates of microorganisms encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix that adhere to biological or inert surfaces [24] [25]. This structured mode of growth represents a primary virulence mechanism for numerous pathogens, enabling persistent colonization and chronic infections that are remarkably refractory to antimicrobial therapy and host immune responses [26]. The biofilm lifecycle progresses through defined stages: initial reversible attachment, irreversible attachment, microcolony formation, maturation, and active dispersal [25]. During maturation, bacteria undergo significant physiological changes and secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that can constitute over 90% of the biofilm's dry mass, creating a protective microenvironment [24].

The clinical significance of biofilms is substantial, with an estimated 65% of all bacterial infections and nearly 80% of chronic wounds involving biofilm components [24]. These infections contribute significantly to healthcare costs, with recent analyses estimating the global economic impact of biofilms exceeds $280 billion annually [24]. Biofilms pose particular challenges in device-associated infections (catheters, prosthetic joints, pacemakers) and chronic conditions such as cystic fibrosis, where they underlie persistent inflammation and tissue damage despite aggressive antibiotic therapy [25] [26].

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a common cause of community-acquired respiratory infections, exemplifies the clinical challenges posed by biofilm-forming pathogens. This cell wall-deficient bacterium forms distinctive biofilm towers during prolonged infection, exhibiting dramatically increased resistance to macrolide antibiotics and complement-mediated host defenses [27]. Understanding the interplay between biofilm-mediated antibiotic resistance and virulence attenuation in M. pneumoniae and other pathogens is essential for developing effective therapeutic countermeasures.

Mechanisms of Enhanced Antibiotic Resistance in Biofilms

Biofilms employ multiple concurrent strategies to achieve remarkable levels of antibiotic tolerance, often exhibiting 10 to 1,000-fold increases in minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) compared to their planktonic counterparts [26]. These resistance mechanisms operate synergistically to protect the bacterial community, representing a multifaceted defense system that poses significant challenges for antimicrobial therapy.

Physical Barrier Function and Reduced Antimicrobial Penetration

The extracellular matrix serves as a formidable physical barrier that significantly impedes antibiotic penetration through several mechanisms. The matrix composition—including polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA (eDNA), and lipids—creates a dense, negatively charged network that can bind and sequester antimicrobial agents [24] [28]. Positively charged aminoglycosides, for example, readily interact with anionic eDNA components, effectively reducing their diffusion into deeper biofilm layers [25]. Additionally, extracellular enzymes within the matrix, such as β-lactamases, can inactivate antibiotics faster than they can diffuse through the biofilm, creating a protective gradient [24]. The reduced and heterogeneous penetration of antimicrobials results in sub-inhibitory concentrations in the biofilm interior, enabling bacterial survival despite apparently adequate dosing [24].

Metabolic Heterogeneity and Persister Cell Formation

Biofilms develop distinct metabolic microenvironments due to nutrient and oxygen gradients from the periphery to the core. This physiological heterogeneity generates subpopulations with varying growth rates and metabolic activities [24] [25]. Cells in nutrient-depleted zones enter slow-growing or dormant states, reducing their susceptibility to antibiotics that primarily target active cellular processes [24]. The deepest biofilm layers are particularly exposed to nutrient-depleted conditions due to diffusion barriers and consumption by peripheral cells, making these regions hotspots for antibiotic tolerance [24]. Within these heterogeneous populations, specialized "persister" cells exhibit multidrug tolerance without genetic mutation [25] [26]. These dormant variants can survive extreme antibiotic challenges and repopulate the biofilm once antibiotic pressure diminishes, contributing significantly to chronic and recurrent infections [25] [28].

Efflux Pump Regulation and Genetic Adaptation

Efflux pumps, which actively export antibiotics from bacterial cells, demonstrate spatially distinct expression patterns within biofilms [24]. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, for instance, specific antibiotic resistance pumps are upregulated in upper regions while showing no change or downregulation in middle sections [24]. This heterogeneous expression creates specialized zones of enhanced antibiotic extrusion. Furthermore, the close proximity of cells within the biofilm matrix facilitates efficient horizontal gene transfer, enabling the dissemination of resistance determinants throughout the community [25]. Bacteria in biofilms can also undergo global transcriptional reprogramming via mechanisms such as the multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) operon in Escherichia coli, which coordinately regulates expression of various genes to establish a multidrug-resistant phenotype [28].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Biofilms

| Resistance Mechanism | Key Components | Functional Impact | Representative Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Barrier | EPS matrix, eDNA, polysaccharides | Binds antibiotics, reduces penetration, enzymatic inactivation | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus |

| Metabolic Heterogeneity | Nutrient/oxygen gradients, slow-growing cells | Reduced susceptibility to growth-dependent antibiotics | Escherichia coli, Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

| Persister Cells | Dormant bacterial subpopulations | Transient multidrug tolerance, biofilm regeneration | S. aureus, P. aeruginosa |

| Efflux Pumps | Membrane transport proteins | Active antibiotic extrusion, zone-specific protection | P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Genetic Adaptation | Horizontal gene transfer, stress responses | Stable resistance development, community-wide protection | ESKAPE pathogens |

Attenuated Virulence Factor Production in Biofilms

The biofilm lifestyle involves a strategic trade-off between protection and pathogenicity, with many pathogens downregulating virulence factor production during biofilm growth to facilitate long-term persistence. This virulence attenuation represents an adaptive response that minimizes excessive host damage and immune activation while maintaining colonization.

Metabolic Reprogramming in Biofilm Communities

As biofilms mature, nutrient availability becomes limited due to high cell density and diffusion barriers, triggering global metabolic changes that impact virulence gene expression [24] [28]. In M. pneumoniae, biofilm formation is associated with significant attenuation of key virulence factors, including hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), and the ADP-ribosylating and vacuolating CARDS toxin [27]. This coordinated downregulation likely reflects resource allocation toward maintenance and matrix production rather than aggressive host damage. Notably, M. pneumoniae biofilm towers show no protection against exogenous H₂O₂ despite reduced endogenous production, suggesting that virulence attenuation is a specific adaptation rather than general metabolic suppression [27].

Quorum Sensing-Mediated Virulence Regulation

Bacteria within biofilms utilize quorum sensing (QS) systems to coordinate gene expression in a population-density-dependent manner [24] [29]. These chemical communication networks precisely regulate the production of virulence factors to optimize host-pathogen interactions. Gram-negative bacteria typically employ acyl-homoserine lactones, while gram-positive species use autoinducing peptides as signaling molecules [24]. In P. aeruginosa, the pqs QS system directly controls the production of elastase, pyocyanin, and other exoproducts [30]. During biofilm development, QS systems can shift from expressing acute virulence factors to promoting persistence traits, balancing the requirements for initial colonization and long-term maintenance [24] [29].

Diagram 1: Quorum sensing regulation of virulence and biofilm formation. Quorum sensing systems coordinate virulence factor production, matrix formation, and persister cell development in response to environmental cues, including host factors and antibiotic exposure. QS inhibitors such as wogonin can disrupt this signaling network.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae Biofilms: A Case Study in Chronic Infection

M. pneumoniae provides a compelling model for understanding the clinical implications of biofilm formation in chronic respiratory infections. This pathogen forms distinctive mound- or dome-shaped biofilm towers during prolonged growth, both axenically and on respiratory epithelial cells [27]. These structures exhibit characteristics highly relevant to chronic disease, including extreme antibiotic resistance and complement evasion.

Antibiotic Resistance Profiles in M. pneumoniae Biofilms

M. pneumoniae biofilms demonstrate staggering levels of macrolide resistance, with biofilm-embedded bacteria surviving erythromycin concentrations up to 512 µg/mL—approximately 8,500-128,000 times the MIC for planktonic cells [27]. This resistance emerges progressively as biofilms mature, suggesting developmental regulation rather than constitutive protection. The resistance spectrum varies among antibiotic classes, with fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines retaining some activity against biofilm-resident bacteria, particularly when used in combination [27].

Table 2: Antibiotic Efficacy Against Mycoplasma pneumoniae Biofilms

| Antibiotic Class | Representative Agent | MIC (Planktonic) | MIC (Biofilm) | Resistance Fold-Increase | Synergistic Combinations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | 0.004-0.06 µg/mL | 512 µg/mL | 8,500-128,000× | Erythromycin + Moxifloxacin |

| Fluoroquinolones | Moxifloxacin | 0.03-0.25 µg/mL | 4-8 µg/mL | 100-250× | Moxifloxacin + Doxycycline |

| Tetracyclines | Doxycycline | 0.125-0.5 µg/mL | 8-16 µg/mL | 60-130× | Doxycycline + Erythromycin |

| Combination Therapy | Erythromycin + Moxifloxacin | - | - | - | 85-95% biofilm eradication |

Novel Therapeutic Approaches for M. pneumoniae Biofilms

Conventional monotherapy often fails against established M. pneumoniae biofilms, necessitating alternative treatment strategies. Checkerboard assays have revealed strong synergistic interactions between antibiotic classes, with dual combinations of erythromycin, moxifloxacin, and doxycycline achieving substantial eradication of pre-formed biofilm towers [27]. These combinations demonstrate efficacy at clinically achievable concentrations, suggesting potential translational applications. Interestingly, M. pneumoniae biofilms show no enhanced resistance to hydrogen peroxide despite producing this compound as a virulence factor during planktonic growth [27]. This vulnerability to oxidative stress may represent an exploitable therapeutic weakness for biofilm-associated infections.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Biofilm Research

Robust experimental systems are essential for investigating biofilm biology and evaluating potential therapeutic interventions. Standardized assays and model systems have been developed to quantify biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, and virulence factor production under controlled conditions.

Biofilm Cultivation and Assessment Techniques

M. pneumoniae biofilm towers are typically cultured in SP-4 broth in 24- or 96-well plates over several days, forming distinct mound- or dome-shaped structures [27]. Crystal violet staining provides a quantitative measure of biofilm biomass, while scanning electron microscopy offers detailed visualization of three-dimensional architecture and cellular organization [27]. For antibiotic susceptibility testing, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays are conducted according to established guidelines for fastidious microorganisms, with serial dilutions of antimicrobial agents in appropriate growth media [27]. Color change indicators in the growth medium facilitate determination of metabolic activity and growth inhibition endpoints.

Virulence Factor Quantification Methods

The attenuated production of virulence factors in biofilms can be quantified through various specialized assays. Hydrogen peroxide production is measured using colorimetric or fluorometric peroxidase-based assays, while cytotoxic effects on eukaryotic cells can be evaluated through lactate dehydrogenase release assays or direct viability staining [27]. For M. pneumoniae, CARDS toxin production can be assessed through immunological methods or ADP-ribosylating activity measurements. Comparative transcriptomics and proteomics provide comprehensive profiles of gene expression differences between biofilm and planktonic populations, identifying key regulatory switches in virulence pathways [27].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for Mycoplasma pneumoniae biofilm research. The methodology involves standardized inoculation procedures, extended incubation to permit biofilm tower development, and multiple assessment techniques to quantify biofilm characteristics, antibiotic resistance, and virulence factor production.

Therapeutic Strategies: Conventional Antibiotics and Anti-Virulence Approaches

The formidable resistance mechanisms employed by biofilms necessitate innovative therapeutic strategies that extend beyond conventional antibiotic monotherapy. Current approaches include optimized antibiotic combinations and emerging anti-virulence compounds that target specific biofilm maintenance pathways.

Antibiotic Combinations with Enhanced Biofilm Activity

Synergistic antibiotic combinations demonstrate significantly improved efficacy against biofilms compared to individual agents. For M. pneumoniae, dual combinations of erythromycin with moxifloxacin, erythromycin with doxycycline, or moxifloxacin with doxycycline achieve 85-95% eradication of pre-formed biofilm towers at clinically relevant concentrations [27]. Similar synergistic interactions have been reported for other bacterial pathogens, including S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, particularly when combining agents with different mechanisms of action and divergent resistance pathways [31]. These combinations appear to target multiple subpopulations within the heterogeneous biofilm community, overcoming the limitations of single-agent therapy.

Anti-Virulence and Quorum Sensing Inhibition

Anti-virulence strategies represent a promising alternative to traditional bactericidal approaches by specifically disrupting pathogenicity without imposing strong selective pressure for resistance development [32] [33]. Quorum sensing inhibitors (QSIs) such as wogonin—a flavonoid derived from Agrimonia pilosa—effectively attenuate P. aeruginosa pathogenicity by interfering with the pqs QS system [30]. Treatment with wogonin downregulates QS-related genes, reduces production of elastase, pyocyanin, and proteolytic enzymes, and inhibits biofilm formation while enhancing bacterial clearance in animal models [30]. Other promising QSIs include terrein, parthenolide, and 4-amino-quinolone-based compounds, which similarly disrupt virulence coordination in various pathogens [32].

Table 3: Emerging Anti-Virulence Compounds with Anti-Biofilm Activity

| Compound | Source/Target | Mechanism of Action | Experimental Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wogonin | Agrimonia pilosa/pqs QS system | Inhibits PQS signal synthesis, downregulates virulence genes | Reduces biofilm formation, attenuates in vivo pathogenicity |

| Terrein | Fungal metabolite | Inhibits QS, reduces elastase/pyocyanin production | Protects mice and C. elegans from P. aeruginosa infection |

| Parthenolide | Medicinal plant | Reduces pyocyanin, protease, and biofilm production | Inhibits swarming motility, disrupts established biofilms |

| Savirin | Synthetic compound | Targets two-component systems, inhibits RNAIII production | Reduces S. aureus skin infection severity in murine models |

| MEDI4893 | Monoclonal antibody | Neutralizes α-hemolysin toxin | Prevents S. aureus-mediated tissue damage in experimental infections |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Biofilm Studies

Advanced research on biofilm formation and therapeutic intervention requires specialized reagents and methodological approaches. The following toolkit highlights essential materials for investigating biofilm biology and evaluating potential anti-biofilm strategies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biofilm Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | SP-4 broth, glucose/citrate media | Biofilm cultivation under defined conditions | Matrix composition varies with carbon source |

| Staining Reagents | Crystal violet, LIVE/DEAD kits | Biofilm biomass and viability quantification | Complementary methods provide different information |

| Antibiotic Standards | Erythromycin, moxifloxacin, doxycycline | MIC determination, combination studies | Clinical formulations vs. research-grade purity |

| QS Inhibitors | Wogonin, synthetic AIP analogs | Anti-virulence mechanism studies | Species-specific QS system differences |

| Matrix Components | DNase I, dispersin B, glycosidases | Matrix disruption studies | Enzyme specificity for different EPS components |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC systems, qPCR instruments | Virulence factor quantification, gene expression | Sensitivity requirements for bacterial metabolites |

Biofilm formation represents a sophisticated virulence strategy that balances enhanced community protection through multilayered antibiotic resistance mechanisms with attenuated virulence factor production to facilitate persistent infection. The case of M. pneumoniae illustrates how these adaptations contribute to chronic respiratory disease and complicate therapeutic interventions. Quantitative analysis reveals that biofilms can increase antibiotic MICs by several orders of magnitude, rendering conventional monotherapy increasingly inadequate. The future of biofilm management lies in combination approaches that integrate optimized antibiotic pairs with targeted anti-virulence agents such as quorum sensing inhibitors. These strategies offer the potential to disrupt pathogenic communities while minimizing selective pressure for resistance development. Further research into the molecular regulation of biofilm development and maintenance will identify additional targets for precisely countering this fundamental bacterial survival strategy.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a significant cause of community-acquired pneumonia in both children and adults worldwide. As a wall-less bacterium, it is inherently resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis, making macrolides—which inhibit bacterial protein synthesis—the cornerstone of treatment [34]. For decades, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin have served as first-line therapeutic agents against Mycoplasma infections. However, the rising global prevalence of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP) strains, particularly in East Asia where resistance rates exceed 80%, presents a substantial clinical challenge [13] [15] [34]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these first-line macrolide agents, focusing on their efficacy against Mycoplasma pneumoniae, mechanisms of action and resistance, and limitations imposed by both bacterial resistance and drug-specific safety profiles. Understanding these aspects is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals working to address the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance.

Macrolide Comparison: Efficacy, Spectrum, and Key Characteristics

The three primary macrolides—azithromycin, clarithromycin, and erythromycin—share a common mechanism of action but differ significantly in their pharmacokinetic properties, antimicrobial spectrum, and clinical applications.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of First-line Macrolides

| Feature | Erythromycin | Clarithromycin | Azithromycin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | First | Second | Second (Azalide) |

| Mechanism of Action | Binds 50S ribosomal subunit, inhibits protein synthesis [35] | Binds 50S ribosomal subunit, inhibits protein synthesis [35] | Binds 50S ribosomal subunit, inhibits protein synthesis [35] |

| Anti-Mycoplasma Activity | Effective against sensitive strains [35] | Effective against sensitive strains [35] | Effective against sensitive strains [35] |

| Key Resistance Mechanism | 23S rRNA mutation (e.g., A2063G, A2064G) [15] [34] | 23S rRNA mutation (e.g., A2063G, A2064G) [15] [34] | 23S rRNA mutation (e.g., A2063G, A2064G) [15] [34] |

| Common Formulations | Oral tablets (250/500 mg), Topical (2%), Ophthalmic (0.5%) [35] | Oral tablets (125/250/500 mg), Suspension (125 mg/5mL) [35] | Oral tablets (100-600 mg), IV (500 mg), Suspension [35] |

| Half-life | Short (~1.5 hours) | Intermediate (~5 hours) | Extended (~68 hours) [35] |

| Unique Properties | Motilin agonist; high GI upset [35] [36] | 14-hydroxy metabolite enhances activity [37] | Extensive tissue penetration & long half-life [35] |

Macrolides exert their antibacterial effect by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit of bacteria, specifically targeting nucleotides in domain V of the 23S rRNA. This binding inhibits protein synthesis by causing premature dissociation of the peptidyl-tRNA complex from the ribosome, ultimately preventing chain elongation [35] [34]. They are considered bacteriostatic antibiotics but can be bactericidal at higher concentrations [35].

While all macrolides are effective against Mycoplasma pneumoniae, their spectrum extends to other atypical pathogens including Legionella species and Chlamydia pneumoniae, making them valuable for empirical treatment of community-acquired pneumonia [35]. Clarithromycin also plays a specific role in Helicobacter pylori eradication regimens [35].

A critical distinction lies in their pharmacokinetic profiles. Azithromycin, with its prolonged half-life and extensive tissue penetration, enables once-daily dosing and shorter treatment courses. In contrast, erythromycin and clarithromycin typically require multiple daily doses [35]. These properties, along with a generally more favorable gastrointestinal tolerance profile, have made azithromycin and clarithromycin preferred over erythromycin in many clinical scenarios [37].

Quantitative Efficacy and Resistance Data

The clinical utility of macrolides is increasingly constrained by the global rise of resistance, particularly in M. pneumoniae, necessitating a clear understanding of quantitative efficacy data.

Table 2: Anti-Mycoplasma pneumoniae Efficacy and Resistance Profiles

| Parameter | Erythromycin | Clarithromycin | Azithromycin | Midecamycin* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC90 (susceptible strains) | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | 16 µg/mL [15] |

| Primary Resistance Mechanism | 23S rRNA mutations (A2063G, A2064G) [15] [34] | 23S rRNA mutations (A2063G, A2064G) [15] [34] | 23S rRNA mutations (A2063G, A2064G) [15] [34] | Not specified in sources |

| Regional Resistance Rate (Pediatrics, East Asia) | Up to 80-100% [13] [34] | Up to 80-100% [13] [34] | Up to 80-100% [13] [34] | Not specified in sources |

| Reported Resistance Rate (Adult Study, Beijing) | 41.7% (within cohort) [15] | 41.7% (within cohort) [15] | 41.7% (within cohort) [15] | Not specified in sources |

| Alternative for Resistant Strains | Not recommended | Not recommended | Not recommended | Promising alternative [15] |

Note: Midecamycin is a 16-membered ring macrolide included for comparison as an investigational alternative. MIC90: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration required to inhibit 90% of isolates.

The most critical limitation of macrolide therapy is high-level resistance, primarily mediated by point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, with A2063G being the most prevalent and consequential substitution [15] [34]. This single mutation significantly alters the drug's binding site, reducing its affinity and rendering the antibiotics ineffective [34].

Epidemiologically, resistance rates show dramatic geographic variation. While generally low in Europe and the Americas (<10%), rates in East Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, and China have soared to 80-100% in recent years [13] [34]. A 2025 study from Osaka, Japan, reported a resistance rate of 72.9% in 2024, indicating a resurgence after a temporary decline during the COVID-19 pandemic [13]. This trend underscores the role of antimicrobial selective pressure and clonal expansion in resistance dissemination [34].

In vitro studies highlight potential alternatives. Midecamycin, a 16-membered-ring macrolide, has demonstrated promising activity against MRMP, with one study reporting an MIC90 of 16 µg/mL, suggesting it may represent a viable therapeutic option, particularly for pediatric populations where tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are used with caution due to toxicity concerns [15].

Mechanisms of Action and Resistance

A detailed understanding of macrolide mechanisms at the molecular level is fundamental for developing strategies to overcome resistance.

Protein Synthesis Inhibition Pathway

The primary antibacterial action of macrolides involves binding to the bacterial 50S ribosomal subunit. The following diagram illustrates this key mechanism and the major resistance pathway.

Experimental Protocol for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Research on macrolide efficacy and resistance relies on standardized laboratory methodologies. The following is a typical protocol for determining Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) against M. pneumoniae.

Objective: To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of macrolide antibiotics against clinical isolates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Materials:

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates: Clinical strains isolated from oropharyngeal swabs [15].

- Reference strain: M. pneumoniae FH (ATCC 15531) as a drug-sensitive control [15].

- Culture media: SP4 broth medium (e.g., OXOID CM0403) [15].

- Antibiotics: Erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, midecamycin standard powders [15].

- Equipment: Microdilution trays, CO₂ incubator, sterile pipettes.

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Harvest actively growing M. pneumoniae cultures and adjust turbidity to 10⁴–10⁵ color-changing units (CCU)/mL in SP4 broth [15].

- Antibiotic Dilution: Prepare two-fold serial dilutions of each macrolide in SP4 broth across the microdilution trays, covering a concentration range from 0.001 µg/mL to 256 µg/mL [15].

- Inoculation: Add an equal volume of the standardized inoculum to each well of the microdilution tray.

- Incubation: Incub trays at 37°C under 5% CO₂ conditions [15].

- MIC Determination: Read plates daily. The MIC is defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that prevents a color change in the phenol red indicator (indicating no bacterial growth) at the time when the growth control wells first show a color change (typically from red to yellow) [15]. Tests should be performed in triplicate for reliability.

- Resistance Breakpoint: Per previous research, a MIC of ≥32 µg/mL is typically used to define resistance for erythromycin, azithromycin, and midecamycin [15].

Limitations Beyond Resistance: Safety and Toxicity

The clinical profile of macrolides is further complicated by a range of non-resistance limitations, particularly concerning adverse effects.

Table 3: Comparative Safety and Toxicity Profiles

| Adverse Effect / Limitation | Erythromycin | Clarithromycin | Azithromycin | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal (Overall) | Very Common (ROR=3.17) [36] | Common (ROR=2.10) [36] | Common (ROR=2.07) [36] | Motilin agonist effect; causes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea [35] |

| QT Prolongation / Torsades de Pointes | High risk (ROR=4.1) [38] | Moderate risk (ROR=4.5) [38] | Lower risk (ROR=7.4)* [38] | Contraindicated in patients with long QT syndrome; caution with concomitant QT-prolonging drugs [35] |

| Hepatotoxicity | Reported [35] | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | Particularly in pregnant women [35] |

| Cardiovascular Toxicity | Valve disorders (ROR=2.3), Ventricular tachyarrhythmias (ROR=3.5) [38] | Valve disorders (ROR=1.8), Ventricular tachyarrhythmias (ROR=3.6) [38] | Heart failure (ROR=1.46), Hypertension (ROR=1.1) [38] | Azithromycin has a distinct CV toxicity profile; requires monitoring [38] |

| Sensorineural Hearing Loss | Reported [35] | Reported [35] | Reported [35] | Often reversible upon discontinuation, but can be permanent [35] |

| Drug-Drug Interactions | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitor [35] | Less interaction potential [35] | Minimal interaction potential [35] | High risk of interaction with carbamazepine, theophylline, terfenadine [35] |

Note: *While azithromycin's ROR for QT prolongation is higher, studies suggest its proarrhythmic potential may be lower than other macrolides due to different patterns of action potential prolongation [38]. ROR = Reporting Odds Ratio from pharmacovigilance studies.

Gastrointestinal toxicity is a class-wide limitation, driven by macrolides' action as motilin receptor agonists that stimulate gastrointestinal motility [35]. A 2025 pharmacovigilance study analyzing FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) data found that among pediatric patients, nearly one-third of adverse event reports for oral macrolides involved GI issues, with vomiting, diarrhea, and nausea being most frequent [36]. Erythromycin demonstrated the highest reporting odds ratio (ROR=3.17) for these events [36].

Cardiovascular toxicity, particularly QT interval prolongation and risk of Torsades de Pointes, is a significant concern [35]. A 2025 analysis of the global VigiBase database confirmed that azithromycin, erythromycin, and clarithromycin were all associated with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and TdP/QT prolongation [38]. Importantly, the cardiovascular toxicity profile differs among agents: azithromycin was uniquely associated with increased reports of hypertension and heart failure, distinguishing it from other macrolides [38].