Autologous Cell-Based Therapies: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of autologous cell-based therapies (ACBT) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Autologous Cell-Based Therapies: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of autologous cell-based therapies (ACBT) for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles and immunological advantages of using a patient's own cells, including the reduced risk of graft-versus-host disease and elimination of donor matching. The content delves into methodological advances in manufacturing, from cell harvesting and genetic engineering to clinical applications in oncology, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune disorders. It addresses critical challenges in scalability, product stability, and hostile microenvironments, offering optimization strategies such as hypoxic preconditioning and gene editing. Finally, the article presents a comparative assessment with allogeneic approaches and examines the evolving clinical trial landscape, regulatory considerations, and future directions for this rapidly advancing field of personalized medicine.

The Foundation of Autologous Cell Therapy: Principles, Advantages, and Mechanisms

Autologous Cell-Based Therapy (ACBT) represents a paradigm shift in personalized medicine, involving the removal, manipulation, and re-introduction of a patient's own cells to treat or prevent a disease, disorder, or medical condition [1]. This approach stands in direct contrast to allogeneic therapies, which utilize cells from donors, and has gained significant traction for conditions ranging from osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal disorders to hematologic malignancies [2] [3]. The fundamental premise of ACBT leverages the patient's own biological material to minimize immunological complications while creating highly personalized therapeutic interventions. As regulatory landscapes evolve globally, ACBT occupies a unique position where some products may be exempt from health product regulation under specific conditions, while others require full pre-marketing approval based on risk classification and degree of cellular manipulation [1]. This technical guide examines the ACBT pipeline from patient to product, addressing scientific, manufacturing, and regulatory considerations for researchers and drug development professionals working in this advancing field.

Autologous vs. Allogeneic Cell Therapies

The distinction between autologous and allogeneic cell therapies represents a fundamental strategic decision in therapeutic development, with each approach presenting distinct advantages and challenges [4]. Autologous therapies use the patient's own cells, ensuring inherent compatibility but requiring complex, individualized manufacturing processes. Conversely, allogeneic therapies utilize donor cells, enabling mass production and "off-the-shelf" availability but necessitating rigorous donor-recipient matching and immunosuppressive strategies to mitigate rejection risks such as graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [4] [5].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Autologous and Allogeneic Cell Therapies

| Characteristic | Autologous Therapy | Allogeneic Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | Patient's own cells | Healthy donor (related or unrelated) |

| Immune Compatibility | Inherently compatible; minimal rejection risk | Requires matching; risk of GvHD and immune rejection |

| Manufacturing Model | Personalized, patient-specific batches | Standardized, large-scale batches |

| Supply Chain | Complex circular logistics | More linear supply chain |

| Production Cost | High (service-based model) | Potentially lower (economies of scale) |

| Regulatory Focus | Safety/efficacy of personalized treatments; chain of identity | Donor eligibility, cell bank characterization, batch consistency |

| Therapeutic Examples | CAR-T therapy for cancer, personalized regenerative therapies | Hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) for leukemia |

The immunological advantages of autologous approaches are significant, particularly the reduced chances of immunological reaction against the final therapy and avoidance of life-threatening complications such as GvHD [5]. Since immune compatibility remains critical in all transplantation areas, autologous strategies present an attractive alternative that typically does not require immunosuppression before treatment [5]. However, this personalized approach introduces substantial challenges in manufacturing scalability, cost structure, and logistical complexity that must be addressed throughout the product development lifecycle.

The ACBT Manufacturing Workflow

The journey from patient to product in ACBT involves a meticulously coordinated sequence of steps requiring specialized infrastructure and rigorous quality control. The entire process demands closed systems and automation to streamline workflow and minimize contamination risk given the personalized nature of each batch [4].

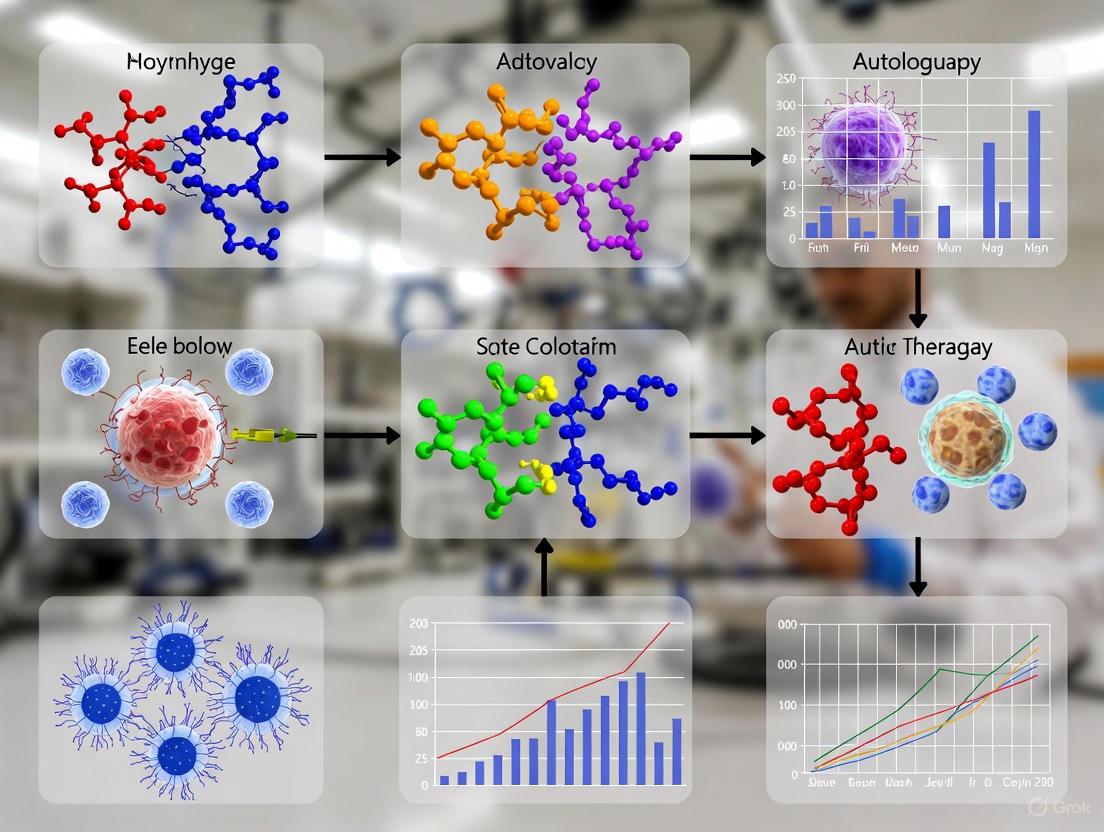

Diagram 1: ACBT manufacturing workflow

This manufacturing workflow highlights several critical challenges unique to autologous therapies. Product stability presents a major constraint, as these therapies exhibit a short ex vivo half-life of as little as a few hours, necessitating manufacturing facilities in close proximity to clinical environments where cellular harvesting and re-administration occur [5]. The entire development process must be conducted with exceptional efficiency not only to preserve product integrity and volume but, most importantly, to treat patients whose prognosis may worsen over time [5]. Additionally, the personalized nature of ACBT introduces substantial heterogeneity between production batches due to patient-specific factors including cellular profile, genotype, phenotype (e.g., HLA type), demographic factors (e.g., age), and medical history, creating difficulties in maintaining consistent quality attributes such as cellular integrity and phenotype [5].

Table 2: Technical Challenges in ACBT Manufacturing and Potential Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge Category | Specific Challenges | Potential Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Logistical Complexities | Circular supply chain; vein-to-vein time pressure; cold chain management; scheduling precision | Proximity of manufacturing to treatment sites; robust tracking systems; closed automated systems |

| Product & Process Variability | Inter-patient variability in starting material; cell quality affected by patient age/health; batch heterogeneity | Patient screening; process parameter adjustments; wider analytical specifications |

| Manufacturing Constraints | Short ex vivo half-life; small-scale parallel processing; contamination risk; chain of identity maintenance | Closed automated systems; process intensification; single-use technologies; digital tracking |

| Cost & Scalability | High manufacturing costs; service-based model; limited economies of scale | Process optimization; automation; analytical advances to reduce failures; strategic pricing models |

Regulatory and Clinical Trial Considerations

The regulatory landscape for ACBT is evolving rapidly as health authorities worldwide grapple with classifying and assessing these innovative therapies [1]. Jurisdictions including the United States, European Union, Canada, and Australia have sought to clarify whether and what cells used in ACBT constitute regulated health products, with variations in how "ACBT products" are defined across regions [1]. Generally, regulatory determination depends largely on risk classification and the degree of cellular manipulation prior to clinical administration, with some ACBT products qualifying for exemptions under specific conditions while others require full pre-marketing approval through appropriate regulatory pathways [1] [3].

A significant development in the ACBT regulatory environment is the proliferation of "pay-to-participate" or "pay-to-play" clinical trials, where patients seeking ACBT are required to pay for participation in trials [1]. This practice raises serious ethical concerns regarding informed consent, therapeutic misconception (where patients mistake research participation for receiving proven clinical therapy), and potential exploitation of vulnerable patients [1]. Evidence suggests this model has become increasingly prevalent as regulators require treatment providers to conduct clinical trials to obtain evidence supporting clinical deployment of various ACBT products [1].

For researchers designing clinical trials for ACBT products, several statistical considerations are particularly relevant. Small clinical trials may benefit from sequential analysis methods, where data are analyzed as results accumulate, allowing studies to be stopped early if results become statistically compelling, potentially reducing average sample size compared to fixed-sample-size designs [6]. Additionally, hierarchical models provide a natural framework for combining information from a series of small clinical trials or for analyzing longitudinal data from crossover studies, potentially increasing statistical power while accounting for individual differences in response patterns [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful development and manufacturing of ACBT products requires specialized research reagents and materials to ensure product safety, efficacy, and consistency. The following table details key solutions essential for various stages of the ACBT workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ACBT Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Separation & Selection | Immunomagnetic beads (e.g., CD4+, CD8+, CD34+ selection); density gradient media; fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) reagents | Isolation of target cell populations from heterogeneous starting material; removal of undesirable cells (e.g., malignant cells) |

| Cell Culture & Expansion | Serum-free media; cytokine cocktails (e.g., IL-2, IL-7, IL-15); growth factors; activation reagents (e.g., anti-CD3/CD28 beads) | Ex vivo cell expansion while maintaining phenotype and function; supporting cell viability and proliferation |

| Genetic Modification | Viral vectors (lentiviral, retroviral); transfection reagents; CRISPR-Cas9 components; mRNA for transient expression | Introduction of therapeutic genes (e.g., CAR constructs); gene editing; cellular reprogramming |

| Quality Control & Analytics | Flow cytometry antibodies; cytokine detection assays; sterility testing kits; endotoxin detection; molecular assays (qPCR, ddPCR) | Assessment of cell identity, potency, purity, and safety; characterization of final product; lot release testing |

| Cryopreservation | Cryoprotectants (e.g., DMSO); controlled-rate freezing media; cell storage bags/vials | Long-term preservation of cell products while maintaining viability and function upon thaw |

Each category plays a critical role in addressing the unique challenges of ACBT development. For instance, advanced cell separation technologies are essential for obtaining high-quality starting material, particularly given the variability in patient-derived cells [5]. Similarly, optimized cell culture systems must support the expansion of therapeutic cells while maintaining their functional properties, a particular challenge when working with cells from patients who may have undergone previous treatments such as chemotherapy that affect cell quality and proliferative capacity [5]. The selection and qualification of these reagent solutions represents a fundamental aspect of process development that directly impacts the quality, consistency, and ultimately the clinical efficacy of the final ACBT product.

Autologous cell-based therapies represent a transformative approach in personalized medicine, offering the potential to address unmet medical needs through patient-specific treatments that minimize immunological complications. The journey from patient to product involves navigating complex scientific, manufacturing, and regulatory challenges, including personalized production workflows, logistical complexities with circular supply chains, and evolving regulatory frameworks. As the field advances, key areas requiring continued innovation include process automation to enhance consistency and scalability, analytical methods to better characterize complex cell products, and regulatory harmonization to facilitate global development. For researchers and drug development professionals, success in this field requires interdisciplinary collaboration and careful consideration of the entire product lifecycle—from cell collection and manipulation to quality control and clinical delivery—to fully realize the potential of these innovative therapies for patients.

The fundamental distinction between autologous (using the patient's own cells) and allogeneic (using donor-derived cells) cell therapies dictates their immunological safety profile. Autologous cell-based therapies are defined by the collection, potential modification, and subsequent reinfusion of a patient's own cells [7]. This approach inherently avoids the two primary immunological challenges of allogeneic cell therapy: Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) and host-mediated graft rejection [7] [8]. GvHD occurs when donor T cells recognize the recipient's tissues as foreign and mount an immune attack [8]. Host-versus-graft (HvG) reactions, or rejection, occur when the patient's immune system identifies the transplanted donor cells as foreign and eliminates them [7]. By utilizing the patient's own cells, autologous therapies sidestep the allo-recognition pathways that trigger these destructive immune responses, forming the core of their immunological advantage.

Mechanisms for Avoiding Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD)

The Pathophysiology of GvHD in Allogeneic Settings

GvHD is initiated when donor-derived T cells, particularly αβ T cells, encounter and recognize recipient alloantigens presented by Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, also known as Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) [7] [8]. This recognition activates donor T cells, leading to their proliferation, differentiation into effector cells, and direct cytolytic attack on host tissues. The severity of GvHD is influenced by the degree of HLA disparity between donor and recipient, with greater mismatch correlating with more severe disease [8].

Autologous Mechanisms for GvHD Prevention

Autologous cell therapies completely circumvent this pathological cascade. Since the cells originate from the patient, they are immunologically identical to the host at the level of HLA presentation. The T-cell receptor (TCR) on reinfused autologous T cells does not recognize host tissue as foreign, thereby preventing the initiation of the GvHD response [7]. This intrinsic safety is a primary driver for the adoption of autologous platforms, particularly for ubiquitous cell therapies like Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cells.

Diagram: GvHD Mechanism and Autologous Avoidance

Mechanisms for Reducing Host Rejection Risks

The Host-versus-Graft (HvG) Response

Even when GvHD is mitigated, allogeneic cell products face elimination by the host's immune system. The HvG response is primarily mediated by host T cells and natural killer (NK) cells that identify the donor cells as foreign [7]. Host CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize donor MHC class I molecules, while CD4+ helper T cells recognize donor MHC class II molecules. NK cells contribute to rejection by detecting the absence of "self" MHC class I molecules or the presence of stress-induced ligands on donor cells.

Autologous Evasion of Host Immunity

Autologous cells, being "self," are inherently invisible to these rejection pathways. They present the patient's own HLA repertoire, so they are not targeted by host T cells via allo-recognition [7]. Furthermore, they express the full complement of "self" markers that inhibit NK cell activation, thus avoiding NK-mediated killing. This allows autologously derived cells to persist in the patient without requiring concomitant immunosuppression, which is often necessary with allogeneic products to prevent rejection but increases the risk of infections and other complications [8].

Table 1: Comparative Immunological Risks of Autologous vs. Allogeneic Cell Therapies

| Immunological Aspect | Autologous Therapy | Allogeneic Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| GvHD Risk | Essentially absent [7] | Significant risk; requires TCR disruption or HLA matching [7] [8] |

| Host Rejection (HvG) Risk | Essentially absent [7] | Significant risk; requires HLA matching or immune suppression [7] |

| Persistence in Patient | Favorable; not recognized as foreign [9] | Can be limited by immune rejection; may require host lymphodepletion [7] |

| Need for HLA Matching | Not applicable (patient is their own donor) | Critical to reduce GvHD and rejection risks [8] |

| Typical Need for Immunosuppression | Not required | Often required to facilitate engraftment and persistence [8] |

Quantitative Analysis of Immunological Outcomes

Clinical data and pharmacological modeling underscore the immunological advantages of autologous systems. Population pharmacokinetic models of autologous CAR-T cells, such as the one developed for Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel), show that these cells can persist for years, with observed persistence exceeding a decade in some patients [9]. This long-term persistence is a direct result of avoiding immune rejection. In contrast, early allogeneic CAR-T products have demonstrated reduced persistence in vivo, partly due to host-mediated clearance [8]. Furthermore, the inter-patient variability in the cellular kinetics (expansion and persistence) of autologous CAR-Ts, while high, is not driven by immunogenic rejection, but rather by factors like patient disease status, lymphodepletion regimen, and product phenotype [9].

Table 2: Key Pharmacokinetic and Clinical Outcome Comparisons

| Parameter | Autologous CAR-T Evidence | Implication for Allogeneic Counterparts |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Persistence | Observed for up to 10+ years [9] | Often limited; subject to host immune rejection [7] [8] |

| Cmax (Peak Expansion) | High inter-patient variability (%CV >30%), spans orders of magnitude [9] | May be influenced by concurrent immunosuppression and early rejection. |

| Durability of Response | Linked to long-term persistence; can provide cures with a single dose [9] | Reduced persistence can potentially impact long-term durability of responses. |

| Risk of Immunogenicity | Low risk of immunogenicity against self-cells [10] | Engineered edits (e.g., TCR knockout) could potentially introduce novel immunogenic epitopes. |

Experimental Validation and Key Methodologies

Core Experimental Protocols for Assessing Immunological Safety

To validate the safety profile of an autologous cell product, specific experimental protocols are employed, often in parallel with allogeneic controls.

1. Protocol for In Vitro GvHD Reactivity Assay (Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction - MLR)

- Objective: To demonstrate the lack of alloreactive T cell response in the final autologous product against host antigens.

- Methodology:

- Step 1: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the patient (representing "host" antigen-presenting cells).

- Step 2: Irradiate the patient PBMCs to halt their proliferation while retaining antigen-presenting capability.

- Step 3: Co-culture the irradiated patient PBMCs with the final autologous cell therapy product (e.g., CAR-T cells) in a standardized culture medium for 5-7 days.

- Step 4 (Control): Set up a positive control by co-culturing the autologous product with irradiated PBMCs from an unrelated, HLA-mismatched donor.

- Step 5: Measure T cell activation in the product, typically via 3H-thymidine incorporation to assess proliferation or by flow cytometry for activation markers (e.g., CD69, CD25).

- Expected Outcome: A well-characterized autologous product will show minimal proliferation/activation in the self-culture (test), but robust proliferation in the allogeneic positive control, confirming the absence of anti-host reactivity.

2. Protocol for Assessing Host-mediated Rejection In Vivo

- Objective: To confirm the extended persistence of autologous cells in an immunocompetent host.

- Methodology (Using Murine Models):

- Step 1: Utilize an immunocompetent, syngeneic mouse model.

- Step 2: Isolate T cells from a donor mouse, engineer them to express a relevant CAR or reporter, and expand them ex vivo.

- Step 3: Infuse these syngeneic cells into a healthy, recipient mouse from the same strain.

- Step 4 (Control): Infuse the same type of cells from the same donor strain into a fully MHC-mismatched, allogeneic recipient mouse.

- Step 5: Monitor cell persistence longitudinally over several weeks. This is typically done by periodic blood sampling and quantification of the engineered cells via flow cytometry (for a reporter) or quantitative PCR (qPCR) for the transgene.

- Expected Outcome: The autologous (syngeneic) cells will show significantly higher and more durable persistence in the blood and tissues compared to the allogeneic cells, which will be rapidly cleared by the recipient's immune system.

Diagram: In Vivo Persistence Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following reagents and platforms are critical for conducting the aforementioned experiments and developing autologous cell therapies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Immunological Profiling

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Application in Autologous Therapy R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral / Retroviral Vectors | Stable gene delivery for CAR or TCR expression. | Engineering patient-derived T cells to express therapeutic transgenes [7] [8]. |

| Cell Isolation Kits (e.g., for T cells, PBMCs) | Immunomagnetic positive/negative selection of specific cell types. | Isolation of target lymphocytes from patient leukapheresis material [7]. |

| Recombinant Human Cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IL-7, IL-15) | Promote T cell activation, expansion, and survival ex vivo. | Critical for the ex vivo culture and expansion of autologous T cells during manufacturing [7]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (e.g., CD3, CD4, CD8, CD69, CD25, CAR detection reagent) | Cell phenotyping and functional analysis. | Characterizing the final product's composition, purity, and activation status; detecting CAR expression [9]. |

| qPCR / ddPCR Assays | Quantitative detection of specific DNA/RNA sequences. | Tracking the pharmacokinetics and persistence of engineered cells in vivo via transgene detection [9]. |

| Automated Cell Processing Systems (e.g., CliniMACS Prodigy) | Integrated, closed-system cell processing. | Standardizing the manufacturing workflow for autologous therapies, reducing contamination risk and variability [11]. |

| Data Management Platforms (e.g., Genedata Biologics) | Centralized data capture and analysis according to FAIR principles. | Integrating and managing complex data from discovery, process development, and translational research [12]. |

Within the framework of autologous cell-based therapies research, the core immunological advantages are clear and compelling. The autologous platform provides a native biological solution to the formidable challenges of GvHD and host rejection that plague allogeneic approaches. This is achieved not through complex genetic engineering or profound patient immunosuppression, but by leveraging the fundamental immune tolerance an individual has for their own cells. While autologous therapies present their own challenges in manufacturing and scalability, their superior and more predictable safety profile from an immunological standpoint makes them a cornerstone of modern regenerative medicine and cellular immunotherapy. Continued research is focused on further enhancing the efficacy of these "living drugs" while maintaining this foundational immunological benefit.

Autologous cell-based therapies represent a paradigm shift in personalized medicine, harnessing a patient's own cells to treat a wide spectrum of diseases through three fundamental biological mechanisms: tissue regeneration, immune modulation, and targeted cytotoxicity. These therapies involve extracting cells from a patient, processing or engineering them ex vivo, and reintroducing them to achieve therapeutic effects [3]. The core advantage of this approach lies in its autologous nature, which minimizes immunogenic responses and rejection risks while enabling highly personalized treatment protocols [13] [3].

The therapeutic landscape of autologous cell therapies has expanded dramatically, encompassing applications in oncology, regenerative medicine, and autoimmune diseases. This expansion is driven by advances in cell engineering, processing technologies, and deepening understanding of underlying biological mechanisms. This technical guide examines the three key therapeutic mechanisms through the lens of current research and clinical applications, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding and advancing this rapidly evolving field.

Tissue Regeneration Mechanisms

Biological Foundations of Regenerative Processes

Tissue regeneration through autologous cell therapies primarily operates through the targeted delivery of growth factors, cytokines, and bioactive proteins that directly stimulate cellular proliferation, differentiation, and matrix remodeling at injury sites [13] [14]. The most established approaches in this category utilize autologous platelet concentrates (APCs), including platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), and concentrated growth factors (CGFs) [14]. These concentrates contain multiple growth factors—including PDGF, VEGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1—that play crucial roles in the regenerative cascade by promoting angiogenesis, stem cell recruitment, and extracellular matrix synthesis [13].

The regenerative mechanism begins with platelet activation and degranulation, which initiates a carefully orchestrated release kinetics of growth factors that modulate the wound healing environment [13] [14]. These factors activate local progenitor cells, enhance vascularization, and directly influence cellular metabolism to create a microenvironment conducive to tissue repair. The individualized preparation of these therapies aligns with precision medicine principles, allowing protocols to be tailored to each patient's biological profile and specific clinical needs [13].

Clinical Applications and Protocol Specifications

Autologous regenerative therapies have demonstrated efficacy across diverse medical specialties. In orthopedics, PRP therapy has shown promise in treating tendinopathy, ligament injuries, muscle strain injuries, and cartilage injuries [3]. In aesthetic medicine, PRP is gaining significance for hair restoration, skin rejuvenation, and scar treatment when combined with lasers, microneedling, and fillers [3]. Autologous skin grafting remains a cornerstone treatment for major burns or tissue damage, though donor area availability and scarring pose limitations [3].

Table 1: Generations of Autologous Platelet Concentrates and Characteristics

| Generation | Representative Type | Preparation Method | Key Components | Structural Characteristics | Primary Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) | Differential centrifugation with anticoagulants | Platelets, leukocytes, growth factors | Liquid form requiring activation | Musculoskeletal injuries, dermatology |

| Second | Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF) | Single-spin centrifugation without anticoagulants | Platelets, leukocytes, cytokines, fibrin matrix | Solid fibrin scaffold with trapped platelets | Oral surgery, chronic wound healing |

| Third | Concentrated Growth Factors (CGFs) | Variable speed centrifugation | Higher concentrations of growth factors, stem cells | Denser fibrin network with extended release | Periodontal regeneration, bone healing |

Experimental Protocol: Preparation of Platelet-Rich Fibrin

Materials and Reagents:

- Patient venous blood sample (10-20 mL)

- Silica-coated plastic vacutainer tubes (without anticoagulant)

- Centrifuge with swing-out rotor system

- Sterile tweezers and scissors

- Incubator (37°C)

Methodology:

- Collect venous blood directly into 10 mL silica-coated tubes without anticoagulant

- Immediately centrifuge at 2700-3000 rpm for 12 minutes using a programmable centrifuge

- Following centrifugation, three distinct layers form: acellular plasma (top), PRF clot (middle), and red blood cell base (bottom)

- Remove the PRF clot from the tube using sterile tweezers, carefully separating it from the underlying erythrocyte layer

- Press the fibrin clot between sterile gauze to create a PRF membrane or process into a particulate form using specialized techniques

- The prepared PRF is ready for application to the surgical site or wound bed

The exclusion of anticoagulants in PRF preparation creates a more natural and gradual polymerization process, resulting in a fibrin matrix that progressively releases growth factors over 7-14 days, unlike PRP which has a more rapid release profile [14].

Immune Modulation Mechanisms

Principles of Immune System Regulation

Immune modulation through autologous cell therapies focuses on resetting or recalibrating the immune system to restore tolerance in autoimmune conditions or enhance antitumor immunity. This mechanism operates primarily through regulatory T cells (Tregs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and engineered chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) constructs designed for immunomodulatory purposes [15]. These approaches target the fundamental dysregulation in autoimmune diseases where the immune system loses ability to distinguish between foreign antigens and self-tissues [15].

The mechanistic basis involves multiple pathways: direct suppression of effector T cells, induction of antigen-presenting cell tolerance, secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β, IL-35), and metabolic disruption of effector cell function through adenosine production or cytokine deprivation [15]. In cancer immunotherapy, immune modulation focuses on overcoming tumor-induced immunosuppression by enhancing T-cell persistence, function, and memory formation [16].

Clinical Applications in Autoimmunity and Oncology

The application of autologous immune modulatory cells has shown remarkable success in treating autoimmune conditions like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), multiple sclerosis (MS), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [15]. In SLE, characterized by loss of immune tolerance and immune complex-mediated inflammation across multiple organs, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has demonstrated efficacy in resetting the immune system [15].

In oncology, combined autologous stem cell transplantation with CAR-T therapy for refractory/relapsed B-cell lymphoma has shown significantly improved outcomes. A 2025 clinical study reported 3-year progression-free survival and overall survival rates of 66.04% and 72.442% respectively with combination therapy, compared to approximately 10-30% with ASCT alone [16].

Table 2: Autologous Immune Cell Therapies in Autoimmune Diseases

| Cell Type | Mechanism of Action | Target Diseases | Development Status | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory T cells (Tregs) | Suppression of autoreactive T cells, anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion | RA, SLE, Type 1 Diabetes | Phase I/II trials | Stability of suppressive phenotype, tissue-specific targeting |

| CAR-Tregs | Antigen-specific suppression via chimeric antigen receptors | MS, SLE, Organ Transplantation | Preclinical and early clinical | Identifying optimal target antigens, controlling expansion |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Paracrine immunomodulation, tissue protection | Crohn's disease, SLE, MS | Phase II/III trials | Heterogeneity of cell products, limited persistence |

| Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) | Immune system resetting after myeloablation | Severe MS, Scleroderma | Approved in some regions | Transplant-related morbidity and mortality |

Experimental Protocol: Treg Expansion and Validation

Materials and Reagents:

- Leukapheresis product or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

- CD4+ CD127lo/- CD25+ isolation kit (magnetic beads)

- X-VIVO 15 or TexMACS medium supplemented with IL-2 (300-1000 IU/mL)

- Anti-CD3/CD28 activator beads

- Rapamycin (100-500 nM)

- Flow cytometry antibodies: CD4, CD25, CD127, FOXP3, CD45RA, Helios

Methodology:

- Isolate CD4+ T cells from leukapheresis product using density gradient centrifugation

- Enrich Tregs using magnetic bead selection for CD4+ CD127lo/- CD25+ population

- Activate Tregs with anti-CD3/CD28 activator beads at 1:3 cell:bead ratio

- Culture in complete medium with high-dose IL-2 (1000 IU/mL) and rapamycin (100 nM) for 14 days

- Perform medium exchange and IL-2 supplementation every 2-3 days

- Harvest cells and validate Treg phenotype through:

- Flow cytometry for CD4+ CD25+ CD127lo/- FOXP3+ expression (>90% purity)

- Demethylation analysis of Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR)

- In vitro suppression assay against CD4+ effector T cells

The addition of rapamycin during expansion promotes Treg stability while inhibiting contaminating conventional T-cell outgrowth, critical for maintaining therapeutic efficacy and safety [15].

Targeted Cytotoxicity Mechanisms

Molecular Foundations of Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity

Targeted cytotoxicity represents the most mechanistically direct approach in autologous cell therapy, employing engineered or enhanced immune cells to specifically identify and eliminate pathological cells, primarily in oncology applications. The cornerstone of this approach is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, which involves genetically modifying a patient's T cells to express synthetic receptors that recognize specific tumor-associated antigens [17] [18]. The CAR construct is a hybrid protein containing an extracellular antigen-recognition domain (typically a single-chain variable fragment from a monoclonal antibody), a hinge region for flexibility, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain comprising costimulatory (e.g., CD28, 4-1BB) and activation (CD3ζ) components [18].

The cytotoxic mechanism operates through direct cell-cell contact, where CAR-T cells identify surface antigens on target cells independent of MHC restriction, forming an immunological synapse that triggers T-cell activation, proliferation, and release of perforin and granzyme cytolytic granules [17] [18]. This results in caspase-mediated apoptosis of the target cell. A single activated cytotoxic cell can eliminate multiple target cells through serial engagement, amplifying the therapeutic effect [19].

Clinical Applications and Efficacy Data

Autologous CAR-T cell therapies have demonstrated remarkable efficacy against hematological malignancies, with six FDA-approved products as of 2024 [18]. The first approvals in 2017 (tisagenlecleucel for ALL and axicabtagene ciloleucel for DLBCL) established this modality as a transformative approach for relapsed/refractory blood cancers [17]. These therapies have shown particularly impressive results in B-cell malignancies targeting CD19 and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in multiple myeloma [17] [18].

Table 3: Efficacy Outcomes of Approved Autologous CAR-T Therapies in Hematological Malignancies

| CAR-T Product | Target Antigen | Indication | Overall Response Rate (%) | Complete Response Rate (%) | Median Duration of Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tisagenlecleucel | CD19 | r/r B-cell ALL | 81% | 60% | Median not reached at 12 months |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | CD19 | r/r LBCL | 82% | 54% | 8.1 months |

| Brexucabtagene autoleucel | CD19 | r/r MCL | 93% | 67% | Median not reached at 12 months |

| Idecabtagene vicleucel | BCMA | r/r Multiple Myeloma | 73% | 33% | 10.7 months |

| Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | BCMA | r/r Multiple Myeloma | 98% | 83% | 21.8 months |

Beyond CAR-T cells, other autologous cytotoxic approaches include autologous immune enhancement therapy (AIET) using natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes expanded ex vivo [19], and memory-like NK cells with enhanced persistence and antitumor activity [20]. These approaches leverage the native cytotoxic mechanisms of immune cells while enhancing their potency through ex vivo activation and expansion.

Experimental Protocol: Autologous CAR-T Cell Manufacturing

Materials and Reagents:

- Leukapheresis product

- Lymphocyte separation medium (Ficoll-Paque)

- X-VIVO 15 or TexMACS GMP-grade medium

- Retrovi ral or lentiviral vector encoding CAR construct

- Recombinant human IL-7 and IL-15

- Anti-CD3/28 activator beads

- Flow cytometry antibodies: CD3, CD4, CD8, CAR detection reagent

Methodology:

- Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from leukapheresis product using density gradient centrifugation

- Activate T cells with anti-CD3/28 beads at 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio

- Transduce activated T cells with viral vector encoding CAR construct (MOI 3-5) by spinoculation (centrifugation at 2000 × g for 90 minutes at 32°C)

- Expand cells in GMP-grade medium supplemented with IL-7 (5 ng/mL) and IL-15 (10 ng/mL) for 10-14 days

- Perform medium exchange and cell density maintenance every 2-3 days

- Harvest cells when expansion criteria met (typically 100-1000-fold expansion)

- Formulate final product in infusion buffer and cryopreserve in vapor phase liquid nitrogen

- Perform quality control assessments:

- Viability (>70%)

- CAR expression (flow cytometry, >30%)

- Sterility (bacterial/fungal culture, mycoplasma PCR)

- Vector copy number (qPCR, <5 copies per cell)

- Potency (cytokine release or cytotoxicity assay)

The manufacturing process typically requires 2-3 weeks, during which patients often receive lymphodepleting chemotherapy (fludarabine/cyclophosphamide) to enhance engraftment and persistence of the infused CAR-T products [17] [18].

Integrated Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

CAR-T Cell Activation Signaling Pathway

The therapeutic efficacy of CAR-T cells depends on precisely orchestrated intracellular signaling events following antigen engagement. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways activated upon CAR engagement with its target antigen.

This signaling cascade begins with CAR engagement of its cognate antigen, triggering phosphorylation of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) within the CD3ζ domain [18]. This primary activation signal is complemented by costimulatory signals through domains such as CD28 or 4-1BB, which enhance T-cell persistence, metabolism, and effector functions [17] [18]. The integrated signaling results in three primary outcomes: T-cell proliferation and expansion, deployment of cytotoxic machinery (perforin, granzymes), and cytokine release (IFN-γ, IL-2) that amplifies the immune response [17].

Platelet Concentrate Signaling in Regeneration

The therapeutic effects of autologous platelet concentrates in tissue regeneration are mediated through growth factor receptor signaling pathways as illustrated below.

Upon application to injury sites, platelets within the concentrates become activated and release growth factors from alpha granules [14]. These factors bind specific tyrosine kinase receptors on target cells (mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells), activating intracellular signaling pathways including MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and SMAD pathways [13] [14]. This signaling cascade results in transcriptional changes that drive the key regenerative processes: angiogenesis through endothelial cell proliferation and migration, extracellular matrix synthesis by fibroblasts, stem cell recruitment and differentiation, and cellular proliferation to repopulate damaged areas [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Autologous Cell Therapy Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Separation | Ficoll-Paque, magnetic bead kits (CD3, CD4, CD56), leukapheresis systems | Isolation of specific cell populations from patient samples | Purity, viability, processing time, GMP compliance |

| Cell Culture Media | X-VIVO 15, TexMACS, RPMI-1640 with supplements | Ex vivo cell expansion and maintenance | Serum-free formulation, cytokine supplements, metabolic requirements |

| Activation Reagents | Anti-CD3/CD28 beads, IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, OKT3 antibody | T-cell activation prior to genetic modification or expansion | Stimulation strength, duration, costimulatory signals |

| Genetic Vectors | Lentiviral, retroviral vectors, CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Genetic modification of cells (CAR expression, gene editing) | Transduction efficiency, insertional mutagenesis risk, safety features |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | Recombinant IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, IL-21, SCF, FLT3L | Promoting cell survival, expansion, and differentiation | Concentration optimization, timing, combination strategies |

| Analytical Tools | Flow cytometry, ELISA, qPCR, cytotoxicity assays | Quality control, potency assessment, characterization | Validation, sensitivity, reproducibility, regulatory compliance |

| Cryopreservation | DMSO, cryoprotectant media, controlled-rate freezers | Cell product storage and stability | Post-thaw viability, functional recovery, container compatibility |

The therapeutic mechanisms of autologous cell-based therapies—tissue regeneration, immune modulation, and targeted cytotoxicity—represent distinct but complementary approaches that leverage the patient's own cellular machinery to address complex diseases. Tissue regeneration strategies harness the body's innate repair mechanisms through precise delivery of growth factors and scaffold materials [13] [14]. Immune modulation approaches reset or recalibrate dysregulated immune responses, showing particular promise in autoimmune diseases [15]. Targeted cytotoxicity employs engineered cellular precision to eliminate pathological cells, revolutionizing oncology treatment [17] [18].

The future advancement of this field will depend on addressing key challenges including manufacturing scalability, cost reduction, protocol standardization, and enhancing safety profiles [21] [3]. Emerging research directions include combining these mechanistic approaches, developing more sophisticated engineering strategies, and expanding applications to new disease indications. As research continues to elucidate the nuanced molecular mechanisms underlying these therapies, more targeted and effective approaches will emerge, further solidifying autologous cell-based therapies as pillars of personalized medicine.

Autologous cell-based therapies represent a transformative frontier in personalized medicine, wherein a patient's own cells are harnessed to repair damaged tissues or combat disease. This paradigm leverages the patient's intrinsic biology, minimizing risks of immune rejection and graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) associated with donor cells [22]. The global market for these therapies is experiencing significant growth, valued at USD 8.64 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 25.78 billion by 2034, expanding at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.55% [23]. This growth is propelled by the rising prevalence of chronic diseases, advancements in regenerative medicine, and a strong trend toward personalized treatment modalities [24] [23]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, focusing on four cornerstone cell types—T-cells, stem cells, invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells, and Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)—within the context of autologous therapy research. We summarize quantitative data, detail experimental protocols, and visualize critical pathways to serve as a foundational resource for ongoing scientific innovation.

Table 1: Global Autologous Cell Therapy Market Overview (2024-2034)

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Market Size in 2024 | USD 8.64 Billion [23] |

| Market Size in 2025 | USD 9.64 Billion [23] |

| Projected Market Size in 2034 | USD 25.78 Billion [23] |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2034) | 11.55% [23] |

| Dominant Region (2024) | North America (40% share) [23] |

| Fastest Growing Region | Asia-Pacific [23] |

Quantitative Data and Clinical Pipeline

The dynamism of the autologous cell therapy field is reflected in its robust market data and extensive clinical pipeline. Oncology, particularly driven by autologous CAR-T cell therapies, is the leading application area, accounting for approximately 30% of the market share [23]. The autologous stem cell-based therapies segment currently dominates the market with a 65% revenue share, underscoring its widespread application and development [23]. As of 2025, there are nearly 1,000 clinical trials nationwide studying CAR T cells, investigating their efficacy beyond hematological cancers into solid tumors and autoimmune diseases [25]. The high number of active clinical trials, exceeding 200 for conditions like Parkinson's disease, arthritis, and heart failure, highlights the expanding therapeutic horizons for these personalized treatments [26].

Table 2: Clinical-Stage Autologous Cell Therapy Candidates (2025 Pipeline Insight)

| Therapeutic Candidate | Developer | Cell Type / Technology | Indication | Development Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JWCAR029 | JW Therapeutics | CAR-T (targeting CD19) | Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) | Preregistration [27] |

| Descartes-11 | Cartesian Therapeutics | Autologous CD8+ CAR-T (targeting BCMA) | Multiple Myeloma | Phase II [27] |

| CNCT19 | CASI Pharmaceuticals | CAR-T | Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | Phase II [27] |

| P-BCMA-101 | Poseida Therapeutics | CAR-T (using piggyBac Transposon System) | Multiple Myeloma | Phase II [27] |

| AUTO4 | Autolus Limited | Programmed T-cell (targeting TRBC1) | T-cell Lymphoma | Phase I/II [27] |

Deep Dive: Core Cell Types

T-cells and Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy

Autologous CAR T-cell therapy involves genetically modifying a patient's own T-cells to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). A CAR is a fusion protein that combines the antigen-binding domain of a monoclonal antibody (single-chain variable fragment, scFv) with the intracellular signaling domains of the T-cell receptor (TCR) and costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD28, 4-1BB) [27]. This engineering redirects T-cells to specifically recognize and eliminate tumor cells expressing the target antigen, independent of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation [27].

The standard manufacturing process begins with leukapheresis to collect peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the patient. T-cells are isolated, activated, and genetically transduced, typically using a lentiviral or retroviral vector, to express the CAR construct. Following a period of ex vivo expansion, the engineered CAR T-cells are infused back into the patient, who has usually undergone lymphodepleting chemotherapy to enhance engraftment and persistence [27]. The therapy has demonstrated remarkable success in hematological malignancies. For instance, a combination therapy of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and CD19-targeted CAR-T for refractory/relapsed B-cell lymphoma improved 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) to 66.04% and 72.44%, respectively [16]. Furthermore, this approach is now being explored for solid tumors and autoimmune diseases, with early reports of "immune reset" leading to durable remission in lupus patients [25].

Stem Cells (Hematopoietic)

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is a well-established procedure, primarily used to reconstitute the bone marrow and immune system after high-dose chemotherapy in cancers like lymphoma and multiple myeloma. The process involves harvesting a patient's own hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), typically from the peripheral blood after mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), followed by cryopreservation. The patient then receives high-dose chemotherapy (conditioning regimen, e.g., BEAM) to eradicate the malignancy, after which the stored HSCs are reinfused [16]. These cells homing to the bone marrow and initiating engraftment, with neutrophil and platelet recovery typically occurring at a median of 14 and 15 days, respectively [16]. A key limitation of ASCT alone is its inability to fully eradicate minimal residual disease (MRD), leading to relapse risks [16]. Consequently, ASCT is increasingly used as a platform for combination therapies, such as with subsequent CAR-T cell infusion, to synergize the intensive tumor debulking of chemotherapy with the targeted, long-term immunosurveillance of engineered cells [16].

Invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) Cells

iNKT cells are a unique lymphocyte subset that bridges innate and adaptive immunity. They are defined by a semi-invariant T-cell receptor (TCR) that recognizes lipid antigens presented by the non-polymorphic MHC class I-like molecule CD1d [28]. Unlike conventional T-cells, iNKT cells exit the thymus as pre-activated effectors and can mount rapid responses without priming [28]. Their therapeutic appeal lies in potent cytotoxicity, extensive immunomodulatory functions (e.g., secreting IFN-γ and IL-4, activating NK and T-cells, promoting dendritic cell maturation), and a inherent lack of alloreactivity, which circumvents GvHD [28]. This makes them ideal candidates for "off-the-shelf" allogeneic therapies.

However, their autologous application is an area of active research, particularly through CAR engineering. CAR-iNKT cells leverage multiple targeting mechanisms—their native TCR, natural killer receptors (NKRs), and an engineered CAR—enabling broader tumor recognition and effective infiltration into immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments (TME) [28]. Clinical evidence is emerging; for example, a patient with metastatic, treatment-refractory testicular cancer achieved a complete and durable remission after receiving an allogeneic iNKT cell therapy (agenT-797), demonstrating the platform's potential [29]. The diagram below illustrates the multi-faceted anti-tumor mechanisms of iNKT cells.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

MSCs are non-hematopoietic, multipotent stromal cells with self-renewal capacity and the potential to differentiate into mesodermal lineages like osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [30]. They can be isolated from various tissues, including bone marrow (BM-MSCs), adipose tissue (AD-MSCs), and umbilical cord (UC-MSCs) [30]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT), MSCs must be: 1) plastic-adherent under standard culture conditions; 2) express surface markers CD73, CD90, and CD105 (≥95%), while lacking expression of hematopoietic markers CD34, CD45, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, and HLA-DR (≤2%); and 3) possess tri-lineage differentiation potential in vitro [30].

The primary therapeutic mechanism of MSCs is largely attributed to their potent paracrine activity and immunomodulatory functions, rather than direct differentiation. They release a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs), which promote tissue repair, angiogenesis, and cell survival [30]. Moreover, MSCs interact with various immune cells (T-cells, B-cells, dendritic cells, macrophages) via direct cell-cell contact and soluble factor secretion (e.g., prostaglandin E2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase) to suppress pro-inflammatory responses and promote an anti-inflammatory, regulatory environment [30]. This makes them powerful candidates for treating autoimmune diseases, graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), and inflammatory disorders.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Combination ASCT and CAR-T Therapy for B-NHL

This protocol is based on a single-arm clinical study involving 47 patients with refractory/relapsed B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (R/R B-NHL) [16].

1. Cell Harvesting and Manufacturing:

- Stem Cell Mobilization and Apheresis: Administer granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood. Perform apheresis to collect a mononuclear cell product containing HSCs.

- Lymphocyte Apheresis: Conduct a separate apheresis procedure to collect approximately 50 ml of peripheral blood lymphocytes.

- CAR-T Cell Generation: Isolate CD3+ T-cells from the apheresed lymphocytes. Genetically modify these T-cells using a viral vector (e.g., lentivirus) to express a CD19-41BB-CAR construct. Expand the transduced T-cells ex vivo to achieve a therapeutic dose.

2. Patient Pre-conditioning (Lymphodepletion):

- Administer high-dose chemotherapy as a conditioning regimen. The specific regimen should be tailored to the disease subtype.

- Standard: BEAM regimen (Bis-chloroethylnitrosourea [BCNU/Carmustine], Etoposide, Cytarabine [Ara-C], Melphalan).

- For patients with central nervous system invasion: TT-BuCy regimen (Thiotepa, Semustine, Busulfan, Cyclophosphamide) [16].

3. Cell Infusion:

- ASCT: Intravenously infuse the cryopreserved, autologous CD34+ HSCs at a dose ranging from 0.4 to 9.5 x 10^6 cells per kg of patient body weight. This is considered Day 0.

- CAR-T Therapy: Within 2 days of the ASCT (on Day 0, 1, or 2), intravenously infuse the manufactured autologous CAR-T cells at a dose ranging from 0.4 to 7.5 x 10^6 cells per kg [16].

4. Monitoring and Endpoint Assessment:

- Engraftment: Monitor absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and platelet counts daily to confirm hematopoietic recovery.

- CAR-T Expansion: Quantify CAR-T cell levels in peripheral blood using flow cytometry or qPCR to track peak expansion and persistence.

- Efficacy Assessment: Evaluate treatment response using computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography (PET) in accordance with the 2014 Lugano Recommendations [16]. Calculate overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS).

- Safety Assessment: Monitor for adverse events, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) using the Penn scale, neurotoxicity, and other potential toxicities graded by CTCAE v5.0 [16].

The workflow for this combination therapy is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol: In Vitro Characterization of MSCs

This protocol outlines the standard procedures for isolating and characterizing MSCs according to ISCT criteria [30].

1. Isolation and Culture of MSCs:

- Tissue Source: Obtain tissue from bone marrow aspirate, adipose tissue (e.g., lipoaspirate), or umbilical cord Wharton's jelly under sterile conditions.

- Processing: Process the tissue to obtain a mononuclear cell fraction. For bone marrow and umbilical cord, use density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque). For adipose tissue, use enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase).

- Plating and Expansion: Plate the cells in tissue culture flasks with a complete medium, such as Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) low glucose, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Passaging: When cultures reach 70-80% confluence, passage the cells using trypsin/EDTA. MSCs are adherent and will exhibit a fibroblast-like, spindle-shaped morphology.

2. Immunophenotyping by Flow Cytometry:

- Harvesting: Harvest MSCs at passage 3-5.

- Staining: Aliquot cells and stain with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against surface markers.

- Positive Marker Panel: Antibodies for CD73, CD90, CD105. The population must show ≥95% positive expression.

- Negative Marker Panel: Antibodies for CD34, CD45, CD14 or CD11b, CD19 or CD79α, HLA-DR. The population must show ≤2% positive expression.

- Analysis: Acquire data on a flow cytometer and analyze to confirm the immunophenotype meets ISCT criteria.

3. Trilineage Differentiation Assay:

- * Osteogenic Differentiation:* Culture MSCs in an osteo-inductive medium containing dexamethasone, ascorbate-2-phosphate, and β-glycerophosphate for 2-3 weeks. Confirm differentiation by staining for mineralized matrix with Alizarin Red S.

- * Adipogenic Differentiation:* Culture MSCs in an adipogenic-inductive medium containing dexamethasone, indomethacin, insulin, and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for 2-3 weeks. Confirm differentiation by staining intracellular lipid droplets with Oil Red O.

- * Chondrogenic Differentiation:* Pellet MSCs and culture in a chondrogenic-inductive medium containing TGF-β (e.g., TGF-β3), dexamethasone, and ascorbate-2-phosphate for 3-4 weeks. Confirm differentiation by staining for proteoglycans with Alcian Blue or Safranin O.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Autologous Cell Therapy Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Example / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral / Retroviral Vectors | Genetic modification of patient T-cells to express Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs) or other therapeutic transgenes. | Delivery of CD19-41BB-CD3ζ CAR construct for B-cell malignancy research [16] [27]. |

| CD3/CD28 Activator Beads | Ex vivo stimulation and expansion of isolated T-cells, mimicking antigen presentation to initiate cell proliferation. | T-cell activation prior to CAR transduction [27]. |

| Cytokine Cocktails (e.g., IL-2) | Maintenance of T-cell health, promotion of proliferation, and prevention of exhaustion during ex vivo culture. | Addition to T-cell and CAR-T cell culture media [27]. |

| Fluorochrome-conjugated Antibodies | Characterization of cell surface markers via flow cytometry for phenotyping and purity assessment. | ISCT characterization of MSCs (CD73, CD90, CD105+; CD34, CD45-); analysis of CAR-T cell products [30]. |

| Lymphodepleting Chemotherapeutics | Creation of a favorable immune environment in vivo to enhance the engraftment and persistence of infused therapeutic cells. | Cyclophosphamide and Fludarabine pre-conditioning for CAR-T therapy; BEAM regimen pre-ASCT [16]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Supplements | Support the growth, expansion, and differentiation of specific cell types under ex vivo conditions. | DMEM with FBS for MSCs; X-VIVO or TexMACS with serum-free cytokines for T-cells/CAR-T cells [30]. |

| Differentiation Induction Kits | Directing the differentiation of stem cells into specific lineages for functional validation studies. | Osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic kits for proving MSC multipotency per ISCT guidelines [30]. |

| qPCR Reagents & Assays | Quantitative tracking of vector copy number, CAR transgene expression, and persistence of engineered cells in vivo. | Monitoring CAR-T cell expansion and longevity in patient peripheral blood post-infusion [16]. |

The focused study of T-cells, stem cells, iNKT cells, and MSCs continues to be the bedrock of innovation in autologous cell-based therapies. The field is moving at an accelerated pace, driven by a deeper understanding of cellular biology and supported by robust clinical and market data. The convergence of these cell types with groundbreaking technologies like gene editing (CRISPR), synthetic biology, and artificial intelligence (AI) for cell characterization and process optimization is set to redefine the possibilities of personalized medicine [23]. While challenges related to manufacturing complexity, cost, and toxicity management persist, the strategic integration of different cell types—such as combining ASCT with CAR-T or engineering powerful effectors like iNKT cells—heralds a new era of sophisticated, effective, and accessible treatments for a broad spectrum of human diseases. For researchers and drug developers, mastering the intricacies of these core cell types is not merely an academic exercise but a critical prerequisite for leading the next wave of therapeutic breakthroughs.

The Evolving Regulatory Landscape for ACBT Products

Autologous cell-based therapy (ACBT) is broadly defined as a medical approach that involves the removal, some level of manipulation or processing, and re-introduction of a person's own cells to treat or prevent a disease, disorder, or medical condition [1]. Unlike allogeneic therapies that use donor cells, ACBT utilizes the patient's own biological material, which presents unique regulatory challenges regarding classification, safety testing, and manufacturing control [31]. The ACBT field has expanded significantly beyond early stem cell applications to include therapies for osteoarthritis, musculoskeletal disorders, sports injuries, and increasingly, autoimmune diseases [1] [32].

The regulatory landscape for ACBT products has evolved considerably as health authorities strive to balance innovation with patient safety. Jurisdictions including the United States (U.S.), European Union (EU), Canada, and Australia have worked to clarify whether and what cells used in ACBT constitute regulated health products [1]. A fundamental regulatory distinction often depends on the level of manipulation performed on the cells prior to clinical administration and the associated risk classification [1]. While increased regulatory clarity has emerged, evidence suggests that patients continue to access regulated but unapproved ACBT products, with some providers exploiting regulatory ambiguities by characterizing regulated products as mere medical procedures [1]. This evolving landscape requires researchers and developers to maintain current knowledge of regional requirements and emerging harmonization efforts.

Current Regulatory Frameworks Across Major Jurisdictions

United States Regulatory Framework

In the United States, ACBT products are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) [33] [34]. These products are classified as human cells, tissues, and cellular- and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps) and regulated as drugs and/or biological products [34]. The FDA's regulatory approach involves several expedited pathways designed to accelerate development of promising therapies:

Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) Designation: Established under the 21st Century Cures Act, RMAT designation provides accelerated approval pathways for regenerative medicines addressing unmet medical needs for serious or life-threatening conditions [34]. This designation offers intensive FDA guidance and potential eligibility for priority review and accelerated approval.

Other Expedited Programs: Additional mechanisms include Fast Track designation, Breakthrough Therapy designation, and Accelerated Approval, which may be available depending on the product profile and targeted condition [34].

Clinical investigations typically require an Investigational New Drug (IND) application submission to FDA, with institutional review board (IRB) approval obtained prior to trial initiation [33]. The FDA has also introduced updated ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice guidelines effective September 2025, which incorporate more flexible, risk-based approaches and embrace innovations in trial design, conduct, and technology [35].

European Union Regulatory Framework

In the European Union, ACBT products fall under the classification of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) and are regulated through a centralized marketing authorization procedure administered by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [34]. This ensures a single evaluation and authorization decision applicable across all EU member states. Key aspects of the EU framework include:

Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT): This specialized committee within EMA assesses the quality, safety, and efficacy of gene therapies based on marketing authorization applications [34].

Expedited Pathways: The EU offers conditional marketing authorization for products with positive benefit-risk balance addressing unmet medical needs, and authorization under exceptional circumstances when comprehensive data cannot be generated due to disease rarity or ethical considerations [34].

The EU maintains specific requirements for starting materials, defining them as materials that will become part of the drug substance, such as vectors used to modify cells, gene editing components, and cells themselves [31]. These must be prepared according to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) principles, with quality assurance falling to the manufacturer's qualified person [31].

Comparative Analysis of FDA and EMA Requirements

Significant regulatory nuances exist between the FDA and EMA regarding ACBT products, particularly in chemistry, manufacturing, and control (CMC) activities. Early decisions in process development, analytical methods, and manufacturing approaches can significantly impact eventual licensure and commercialization in these jurisdictions [31].

Table 1: Key FDA and EMA CMC Requirements for Cell and Gene Therapy Products

| Regulatory CMC Consideration | FDA Position | EMA Position |

|---|---|---|

| Potency testing for viral vectors for in vitro use | Validated functional potency assay essential to assess efficacy of drug product used in pivotal studies | Infectivity and expression of transgene generally sufficient in early phase with less functional assays acceptable at later stages |

| Donor testing requirements for cell therapies | Governed by 21 CFR 1271 subpart C; Expected to be tested in CLIA-accredited labs | Governed by EUTCD; Expected to be handled and tested in-licensed premises and accredited centres |

| Number of batches for Process Validation (PV) | Not specified, but must be statistically adequate based on variability | Generally, three consecutive batches; Some flexibility allowed |

| Use of surrogate approaches in PV | Allowed, but must be justified | Allowed only in case of a shortage in starting material |

| Stability data in support of comparability | Thorough assessment including real-time data for certain changes | Real-time data not always needed |

| Use of historical data in support of comparability | Inclusion of historical data recommended | Comparison to historical data not required/recommended [31] |

Additional distinctions emerge in specific technical requirements. For viral vector testing, the FDA classifies in vitro viral vectors used to modify cell therapy products as a drug substance, while the EMA considers these to be starting materials [31]. Regarding replication competent virus (RCV) testing, the EMA considers that once absence has been demonstrated on the in vitro vector, the resulting genetically modified cells do not require further RCV testing, whereas the FDA requires that the cell-based drug product also needs testing [31].

Manufacturing and Control Strategies for Global Development

Starting and Raw Materials Definition

The definition and control of starting materials represents a fundamental regulatory distinction between FDA and EMA frameworks. For CGT products that require human material in their manufacture, such as patient cells, both agencies require regional donor testing requirements, with the EMA requiring some donor testing even for autologous material [31]. This difference necessitates careful planning for global development programs to ensure compliance in both jurisdictions from the earliest stages of process development.

Demonstrating Comparability

Comparability assessment following manufacturing changes presents particular challenges for ACBT products. Currently, CGT products fall outside the scope of the ICH Q5E guideline on comparability of biotechnological/biological products, though a new annex to address CGT-specific compatibility challenges is in development [31]. In the interim, regional guidances apply:

EU Approach: EMA provides a 'Questions and Answers' document on comparability considerations, with multidisciplinary guidance for medicinal products containing genetically modified cells [31]. A multidisciplinary EU guideline for demonstrating comparability for CGTs undergoing clinical development becomes effective in July 2025 [31].

US Approach: The FDA has issued draft guidance on comparability for CGT products (July 2023), reflecting current FDA thinking on CGT comparability [31].

Both agencies emphasize the importance of potency testing in comparability exercises, though differences exist in requirements for stability data and the use of supportive development data [31]. Both regulatory bodies agree that the extent of testing should increase with the stage of clinical and product development, employing a risk-based approach to evaluate the impact of manufacturing changes [31].

ACBT Regulatory Development Pathway: This diagram illustrates the key stages in ACBT product development from preclinical research through market authorization, highlighting regulatory interactions and expedited pathway opportunities.

Emerging Trends and Ethical Considerations

Patient Perspectives and Experience

Research on patient experiences with ACBT reveals several important trends that inform regulatory policy. A 2023 survey of 181 participants who had received or were undergoing ACBT treatment identified critical themes in patient engagement with these therapies [2] [1]:

Healthcare Provider Influence: Healthcare providers play a prominent role throughout the patient journey, significantly influencing treatment decisions and perceptions of risk and benefit [1].

Informational Practices: Gaps exist in the quality and completeness of information provided to patients during clinical encounters, potentially impacting informed consent [1].

Pay-to-Participate Trials: There is a high prevalence of "pay-for-participation" or "pay-to-play" clinical trials, where patients seeking ACBT pay to participate in trials [2] [1]. This practice raises ethical concerns regarding informed consent, therapeutic misconception, and potential exploitation of vulnerable patients [1].

Regulatory Knowledge Gaps: Patients demonstrate significant gaps in understanding the regulatory status of ACBT products and the distinctions between approved treatments, investigational therapies, and unproven interventions [1].

Evolving Clinical Trial Designs

The regulatory environment for ACBT clinical trials is evolving to incorporate more flexible, efficient approaches. The ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice guidelines, finalized for September 2025 implementation, emphasize risk-based quality management and increased flexibility to support modern trial designs [35]. Key updates include:

Proportionality and Relevance: Promoting approaches that are proportionate to the risks of the trial and relevant to the context of the research [35].

Quality by Design: Advancing quality by design principles throughout trial planning and conduct [35].

Technology Integration: Encouraging the use of technology and innovations in clinical trial conduct while maintaining participant protection and data reliability [35].

Additional developments include the FDA's push for diversity in clinical trials, requiring diversity action plans for certain trials to ensure adequate representation of underrepresented populations [36]. Furthermore, decentralized trial models incorporating telemedicine and remote monitoring are becoming more prevalent, introducing new considerations for regulatory compliance and ethical oversight [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ACBT Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in ACBT Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Separation Media | Isolation of specific cell populations from patient samples | Density gradient media for mononuclear cell separation; Closed-system automated platforms preferred for clinical grade |

| Cell Culture Media | Ex vivo expansion and maintenance of autologous cells | Xeno-free formulations required for clinical use; Serum-free media with defined components for regulatory compliance |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | Direction of cell differentiation and expansion | Research-grade vs. GMP-grade distinctions; Purity and potency testing requirements for clinical applications |

| Gene Editing Components | Genetic modification of autologous cells (where applicable) | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, TALENs, or viral vectors; Regulatory considerations for genetically modified cells |

| Viral Vectors | Delivery of genetic material to autologous cells | Lentiviral, retroviral, or AAV systems; Testing for replication competent virus (RCV) required [31] |

| Cryopreservation Media | Long-term storage of cell products | Defined formulation without animal components; Validation of post-thaw viability and functionality |

| Quality Control Assays | Characterization of final cell product | Potency assays, sterility testing, identity and purity assessments; Validation according to regulatory expectations [31] |

ACBT Manufacturing Workflow: This diagram outlines the key stages in autologous cell-based therapy manufacturing, highlighting critical process steps and quality control checkpoints.

The regulatory landscape for ACBT products continues to evolve rapidly as health authorities gain experience with these complex therapies and developers generate additional evidence regarding their safety and efficacy. Several key trends are likely to shape future regulatory developments:

Increased Harmonization: Efforts to harmonize regulatory requirements across jurisdictions will continue, potentially reducing development complexity for global programs. The development of a new Annex to ICH Q5E specifically addressing CGT comparability challenges represents one such initiative [31].

Advanced Manufacturing Technologies: Automation in cell isolation, culture, and differentiation processes is streamlining manufacturing, with robotic platforms now handling up to 80% of routine cell processing steps in leading facilities [37]. These advances may prompt updated regulatory guidance on manufacturing controls.

Analytical Advancements: The adoption of AI-driven predictive modeling and data analytics is enhancing decision-making in therapy customization, patient stratification, and outcome prediction [37]. Early studies indicate AI integration can enhance treatment response prediction accuracy by up to 30% [37].

Novel Therapeutic Applications: The expansion of autologous therapy applications into autoimmune diseases, liver regeneration, and ophthalmology will require continued regulatory adaptation to address new safety and efficacy considerations [37] [32].

For researchers and developers navigating this complex environment, successful global development strategies will require thorough understanding of both FDA and EMA region-specific requirements while identifying opportunities for harmonization to streamline CMC development [31]. Engaging with regulatory agencies early in development, implementing robust comparability protocols, and maintaining focus on patient-centric trial designs will be essential for advancing promising ACBT products through the regulatory pipeline to patient access.

From Bench to Bedside: Manufacturing Processes and Therapeutic Applications

Autologous cell therapies represent a groundbreaking approach in personalized medicine, fundamentally different from traditional pharmaceuticals or allogeneic (donor-derived) cell therapies. These treatments are manufactured on a per-patient basis, creating a bespoke therapeutic product for each individual [38]. The process harnesses a patient's own cells to treat a variety of conditions, including specific cancers, autoimmune diseases, and genetic disorders [38]. This entirely personalized approach, while clinically powerful, introduces significant manufacturing complexities. The core workflow remains consistent, comprising four critical stages: the collection of cells from the patient, their modification and expansion in a specialized facility, and the final reinfusion of the finished product back into the same patient [38]. This guide details the technical execution of each stage, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals working within this advanced therapeutic domain.

The Four Core Stages of the Autologous Workflow

The journey of an autologous cell therapy is a logistically intensive, time-sensitive sequence. Each stage must be meticulously controlled and tracked to ensure the final product's safety, identity, potency, and purity.

Stage 1: Cell Collection and Initial Processing

The manufacturing process initiates with the procurement of the patient's own starting cellular material.

- Collection Method: The most common method for collecting lymphocytes, such as those used in CAR-T therapies, is leukapheresis [39]. This procedure involves drawing blood from the patient, separating out the white blood cells, and returning the other components (red blood cells, plasma, and platelets) to the patient's circulation. For other therapies, starting material may be derived from tissue biopsies (e.g., for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes) or bone marrow aspirates [39].