Autologous vs. Allogeneic Cell Therapy: A Comprehensive Efficacy Analysis for Drug Development

This article provides a comparative analysis of autologous and allogeneic cell therapy efficacy for researchers and drug development professionals.

Autologous vs. Allogeneic Cell Therapy: A Comprehensive Efficacy Analysis for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of autologous and allogeneic cell therapy efficacy for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles, including immunological compatibility and cell sourcing, and examines clinical applications across hematologic malignancies, solid tumors, and autoimmune diseases. The content addresses key manufacturing and safety challenges, such as graft-versus-host disease and product variability, and presents validation strategies through clinical trial data and meta-analyses. Finally, it discusses future directions, including genetic engineering and scalable manufacturing, to guide therapeutic development and clinical implementation.

Defining the Battle: Core Concepts and Biological Mechanisms of Cell Therapies

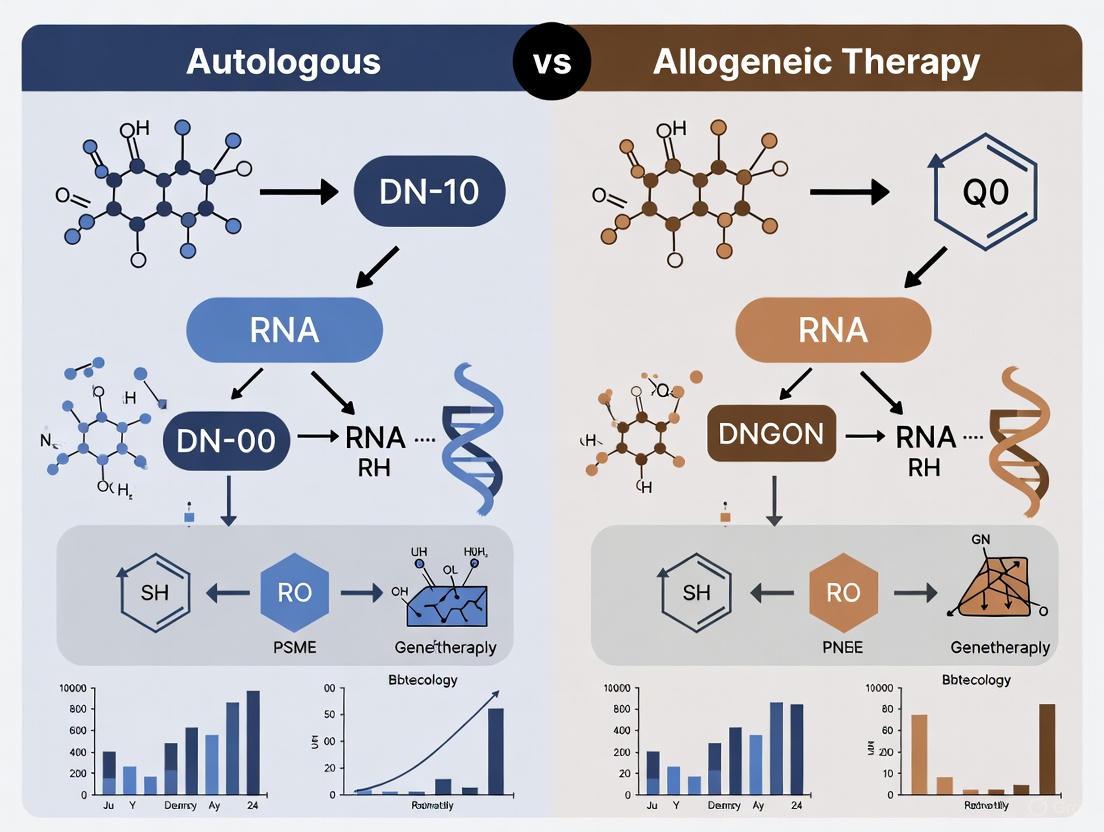

The development of modern cell therapies is fundamentally guided by the origin of the therapeutic cells, creating a primary division between autologous (self-derived) and allogeneic (donor-derived) approaches. This distinction influences every aspect of therapeutic development, from manufacturing and logistics to clinical efficacy and safety profiles. Autologous cell therapy involves the extraction, manipulation, and reinfusion of a patient's own cells, ensuring perfect immune compatibility but requiring complex, personalized manufacturing [1] [2]. In contrast, allogeneic cell therapy utilizes cells from a healthy donor, enabling "off-the-shelf" availability and mass production but introducing potential immune rejection risks [3] [1]. Within the broader context of therapy efficacy research, understanding these foundational differences is critical for selecting the appropriate therapeutic strategy for specific disease indications and patient populations.

The choice between autologous and allogeneic sources extends beyond mere cell origin; it represents a strategic decision that impacts scalability, cost, treatment timelines, and ultimately, patient access. As the field advances, research continues to address the inherent challenges of both approaches, particularly through genetic engineering and process optimization, to enhance the therapeutic potential of cell-based treatments across a widening spectrum of medical conditions [3] [4].

Fundamental Definitions and Key Characteristics

Autologous Cell Therapy

Autologous cell therapy is a highly personalized treatment modality where cells are harvested from the patient, processed or manipulated ex vivo, and then reinfused back into the same individual [1] [2]. This approach creates a closed, patient-specific system that fundamentally avoids immune rejection, as the treated immune system recognizes the therapeutic cells as "self." A prominent clinical example is Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy for hematological malignancies, where a patient's own T-cells are genetically engineered to target specific cancer cells before being reinfused [2]. Other applications include autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and the use of a patient's somatic cells for reprogramming into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for regenerative purposes, such as in Parkinson's disease research [4].

Allogeneic Cell Therapy

Allogeneic cell therapy involves the use of cells derived from a donor who is genetically distinct from the recipient [1]. These cells can come from a matched (HLA-compatible) donor or be developed as universal "off-the-shelf" products from donor cell banks or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines [3] [2]. A key advantage is immediate availability, eliminating the weeks-long manufacturing delay associated with autologous therapies, which is a critical factor for acute conditions [2]. Examples include allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) for leukemia and the emerging use of allogeneic CAR-NK cells from cord blood or iPSCs for treating cancer and autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus [3] [5]. The primary challenge remains the risk of immune complications, such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), where donor immune cells attack the patient's tissues, or host-mediated rejection of the therapeutic cells [1] [4].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Autologous vs. Allogeneic Cell Therapies

| Characteristic | Autologous Therapy | Allogeneic Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | Patient's own cells [1] | Healthy donor (related/unrelated) [1] |

| Immune Compatibility | High (No rejection risk) [2] | Variable (Risk of GVHD/rejection) [1] |

| Manufacturing Model | Personalized, patient-specific batch [1] | Standardized, "off-the-shelf" batch [3] [1] |

| Typical Production Time | Several weeks [4] | Pre-manufactured, available on demand [2] |

| Scalability | Challenging (Scale-out) [1] | Favorable (Scale-up) [1] |

| Cost Structure | High (Service-based model) [4] | Potentially lower (Mass production) [4] |

Clinical Efficacy and Safety Data

Recent clinical trials provide compelling data on the efficacy and safety profiles of both autologous and allogeneic cell therapies across different disease areas, enabling a more nuanced comparison.

Efficacy Outcomes from Recent Trials

In the oncology domain, a phase 2 trial investigating a novel "sandwich" strategy for Philadelphia chromosome-negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) demonstrated the potent efficacy of an autologous approach. The therapy combined sequential CD22/CD19 CAR-T cell therapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT). With a median follow-up of 28 months, the regimen achieved a remarkable 2-year overall survival rate of 97% and a 2-year leukemia-free survival rate of 72%. Deep molecular remissions were induced, with 80% of patients maintaining continuous measurable residual disease (MRD)-negative status [6].

In the autoimmune field, a 2025 case series from China evaluated an allogeneic CD19 CAR Natural Killer (NK)-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The results indicated promising efficacy, with 67% (6 out of 9) of patients with more than 12 months of follow-up attaining DORIS remission and lupus low disease activity state. This suggests that allogeneic CAR-NK therapy can be a potent option for treating autoimmune diseases, potentially addressing the limitations of autologous CAR-T cells [5].

Safety and Tolerability Profiles

The safety profiles of the two approaches also show distinct characteristics. The autologous CAR-T plus auto-HSCT "sandwich" therapy in B-ALL was reported to be well-tolerated. Notably, no instances of severe (grade ≥3) cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) were observed. Mild CRS occurred in a subset of patients, and while all patients experienced expected grade 3-4 hematotoxicity, no severe organ toxicity was reported. The study highlighted a non-relapse mortality rate of 0%, which compared favorably to an external allogeneic HSCT control group that had a 15% rate [6].

For the allogeneic CD19 CAR-NK therapy in SLE, the safety profile was also favorable. Cytokine release syndrome was reported in only one (6%) of the 18 patients, and it was low-grade (grade 1). The study reported no observed neurotoxicity, other severe adverse events related to the therapy, or dose-limiting toxicities. This indicates that allogeneic CAR-NK therapy might mitigate some of the significant safety concerns, particularly severe CRS and neurotoxicity, which are known risks associated with autologous CAR-T therapy [5].

Table 2: Comparative Clinical Trial Outcomes in Specific Indications

| Parameter | Autologous Approach (B-ALL) [6] | Allogeneic Approach (SLE) [5] |

|---|---|---|

| Therapy Description | CD22/CD19 CAR-T + Auto-HSCT "Sandwich" | Allogeneic CD19 CAR NK-Cell Therapy |

| Study Design | Phase 2 Trial (n=37) | Case Series (n=18) |

| Key Efficacy Result | 97% 2-year Overall Survival | 67% DORIS Remission (at >12 months) |

| Key Safety Finding | 0% Severe (≥Grade 3) CRS/ICANS | 6% Incidence of Low-Grade (Grade 1) CRS |

| Mortality | 0% Non-Relapse Mortality | Not Reported |

| Notable Risk | Relapse (20%, all CD19+) | No dose-limiting toxicities observed |

Manufacturing and Logistics Comparison

The operational backbone of cell therapies reveals a stark contrast between autologous and allogeneic paradigms, impacting everything from production to patient delivery.

Manufacturing Workflows

The manufacturing journey for autologous therapies is circular and patient-specific. It begins with apheresis at a clinical center to collect the patient's cells, which are then shipped to a manufacturing facility. Here, cells undergo complex, small-scale processes including activation, genetic modification (e.g., viral transduction), expansion, and formulation into a final drug product. This product is cryopreserved and shipped back to the treating hospital for infusion, with the entire "vein-to-vein" time being a critical variable [1] [4]. Each batch is unique to a single patient, requiring rigorous chain-of-identity tracking and adaptable processes to accommodate variability in starting material from sick patients [1].

In contrast, allogeneic manufacturing follows a more linear, scalable path. Cells are sourced from healthy donors, cord blood, or master iPSC banks. The processes—activation, engineering, and expansion—occur at a much larger scale, often in bioreactors, to produce thousands of doses from a single batch. The final "off-the-shelf" products are cryopreserved and stored in inventories, ready for immediate distribution to treating physicians, eliminating the lengthy manufacturing wait [1] [2]. This allows for standardized processes, rigorous quality control on a batch-by-batch basis, and comprehensive pre-release testing [1].

Supply Chain and Scalability

The logistical implications of these two models are profound. The autologous supply chain is a complex, circular network that necessitates robust cold chain logistics, precise scheduling to minimize cell handling times, and an unwavering focus on chain-of-identity to prevent patient-product mix-ups. Scalability is achieved through "scale-out" – establishing multiple, parallel, small-scale production lines, which is capital and resource-intensive [1]. The high degree of personalization, coupled with low utilization of manufacturing capacity per patient, results in a high cost structure, making it a "service-based" model [4].

The allogeneic supply chain is more linear and resembles that of traditional biopharmaceuticals. It allows for bulk processing, long-term storage, and distribution from a central inventory. Scalability is achieved through "scale-up" – using larger bioreactors to produce greater quantities per batch, which leads to economies of scale and a potentially lower cost per dose [1] [4]. This model is financially appealing to the biopharmaceutical industry as it enables broader patient access and more sustainable commercial production [4].

Table 3: Manufacturing and Logistics Comparison

| Aspect | Autologous Therapy | Allogeneic Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Supply Chain Model | Circular, patient-specific [1] | Linear, centralized inventory [1] |

| Scalability Strategy | Scale-out (multiple parallel lines) [1] | Scale-up (larger batch sizes) [1] |

| Production Focus | Customization for individual patients [1] | Standardization for patient populations [1] |

| Key Logistical Challenge | Minimizing vein-to-vein time [1] | Managing donor cell variability & quality [1] |

| Cost Drivers | Custom manufacturing, complex logistics [4] | Donor screening, cell banking, immunosuppression [2] [4] |

| Batch Consistency | High variability (patient-derived) [4] | High consistency (donor-screened) [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Translating cell sources into viable therapies requires specialized experimental workflows and reagents. The following section outlines a core protocol for evaluating allogeneic cell therapies and the essential tools for this research.

Detailed Methodology: Assessing Allogeneic CAR-NK Cell Efficacy & Safety

The following protocol is adapted from a 2025 clinical case series investigating allogeneic CD19 CAR-NK cells in systemic lupus erythematosus [5], providing a template for preclinical assessment of allogeneic therapies.

1. Cell Sourcing and Engineering:

- Cell Source: Isolate NK cells from healthy donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or obtain from a cord blood bank or an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line [3] [5].

- Genetic Modification: Engineer cells using lentiviral or retroviral transduction to express a CD19-targeting Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR). The CAR construct typically includes an extracellular anti-CD19 scFv, a transmembrane domain (e.g., CD28 or CD8), and intracellular signaling domains (e.g., CD3ζ plus 4-1BB or CD28) [3].

- Expansion: Cultivate and expand the transduced CAR-NK cells ex vivo in a GMP-compliant facility using media supplemented with cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IL-15) to achieve the target cell dose [5].

2. Preclinical In Vivo Model:

- Animal Model: Utilize immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG or NOG strains) engrafted with human CD19+ target cells (e.g., B-cell lymphoma lines for oncology or human PBMCs for autoimmune modeling).

- Treatment Groups: Randomize animals into groups receiving: a) allogeneic CAR-NK cells, b) unmodified allogeneic NK cells (control), and c) vehicle only (control).

- Dosing: Administer cells via intravenous injection at a predefined dose (e.g., (0.75 \times 10^9) cells per dose in the clinical study [5]). Multiple doses may be administered.

3. Endpoint Analysis:

- Efficacy: Monitor tumor burden via bioluminescent imaging (oncology) or measure biomarkers of autoimmune activity (e.g., anti-dsDNA antibodies in SLE models) over time. Assess survival and disease remission rates.

- Safety/Toxicity: Monitor animals daily for signs of Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS; e.g., weight loss, lethargy, hypothermia) and neurotoxicity. Score CRS severity using established grading systems. Upon study termination, analyze blood serum for cytokine levels (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-6) and major organs for histopathological signs of damage or Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Cell Therapy Research

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Lentiviral / Retroviral Vectors | Delivery system for stable genomic integration of CAR transgenes into effector cells (T-cells, NK cells) [2]. |

| Cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IL-15) | Critical components of cell culture media to promote activation, survival, and ex vivo expansion of immune cells [5]. |

| Lymphodepleting Chemotherapy (e.g., Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide) | Pre-conditioning agents used in vivo to suppress the host immune system, creating a favorable environment for the engraftment and persistence of administered cells [5]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Panel of fluorescently-labeled antibodies for characterizing cell phenotypes (e.g., CD3, CD56 for NK cells), confirming CAR expression, and assessing target cell depletion (e.g., CD19+ B-cells) [5] [6]. |

| Cryopreservation Medium | Formulation containing DMSO and serum/proteins to enable long-term storage of cell therapy products in liquid nitrogen without loss of viability or function [1]. |

The comparative analysis of autologous and allogeneic cell sources reveals a landscape of complementary strengths and challenges. The choice between these two foundational paradigms is not a matter of declaring a universal winner but of strategically matching the approach to the clinical and commercial context. Autologous therapies offer the key advantage of immune compatibility, making them powerful for personalized, long-term interventions, as evidenced by high remission rates in B-ALL, albeit with complex logistics and high costs [6] [4]. Allogeneic therapies, conversely, offer the transformative potential of "off-the-shelf" immediacy and superior scalability, with emerging data showing promising efficacy and manageable safety profiles in diseases like SLE, though they must navigate the hurdles of immune rejection [3] [5].

Future directions in efficacy research will likely focus on convergence and optimization. For autologous therapies, efforts are centered on streamlining manufacturing, automating processes, and reducing vein-to-vein time to improve accessibility [1] [4]. For allogeneic therapies, the research frontier involves advanced genetic engineering—using technologies like CRISPR to create "hypoimmune" universal donor cells that evade host immune detection, thereby mitigating the risks of rejection and GVHD without the need for extensive immunosuppression [3] [2]. As both fields evolve, the ongoing synthesis of clinical data and manufacturing innovation will continue to refine these paradigms, ultimately expanding the arsenal of curative treatments available to patients.

The advent of cell-based immunotherapies represents a paradigm shift in cancer treatment, particularly for hematological malignancies. These therapies are broadly categorized into autologous approaches (using the patient's own cells) and allogeneic approaches (using donor-derived cells) [4]. While autologous CAR-T therapies have demonstrated remarkable efficacy, their widespread application is constrained by manufacturing limitations, including lengthy production times, high costs, and significant patient-to-patient variability in product quality [7] [8]. Allogeneic, or "off-the-shelf," cell therapies from healthy donors offer a promising alternative with potential for immediate administration, scalable production, and more consistent product quality [7] [8] [9].

However, the clinical application of allogeneic cell therapies introduces complex immunological challenges, primarily Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) and Host-versus-Graft Reaction (HVGR). GvHD occurs when immunocompetent T cells from the donor graft recognize and attack recipient tissues, while HVGR involves the recipient's immune system rejecting the donor cells [8] [10]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these immunological barriers, detailing their underlying mechanisms, experimental approaches for investigation, and current strategies for mitigation within the context of autologous versus allogeneic therapy efficacy.

Immunopathological Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis

Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) in Allogeneic Transplants

GvHD is a systemic disorder that progresses through a well-defined series of immunological phases, beginning with tissue damage and culminating in targeted organ destruction [7] [10]. The process initiates when conditioning regimens (chemotherapy or radiation) damage host tissues, releasing inflammatory cytokines and activating host Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs) [11] [10]. Donor T cells are then activated upon encountering alloantigens presented by host APCs, leading to their proliferation and differentiation into inflammatory T-helper cells (Th1, Th17) and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [11]. Finally, these activated effector cells migrate to target organs—primarily the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and liver—causing apoptosis and tissue damage through direct cytotoxicity (perforin/granzyme, Fas/FasL) and cytokine-mediated inflammation [7] [10].

The diagram below illustrates the three-phase pathogenesis of GvHD:

Table 1: Clinical Manifestations and Target Organs in GvHD

| Target Organ | Clinical Manifestations | Histopathological Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | Maculopapular rash (palms, soles, shoulders), pruritus, pain, bullous lesions in severe cases | Vacuolization of epidermis, dyskeratotic bodies, subepidermal cleft formation, dermal-epidermal separation [10] |

| Gastrointestinal Tract | Diarrhea (secretory, may be bloody), abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, mucositis | Apoptosis of epithelial cells, dilated crypts, crypt destruction, villus atrophy, neutrophilic infiltration [10] |

| Liver | Elevated bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, hepatomegaly, pale stool/dark urine | Dysmorphic small bile ducts, portal inflammation [10] |

GvHD is clinically categorized as acute (aGvHD) or chronic (cGvHD), distinguished by timing and pathological features. aGvHD typically occurs within 100 days post-transplant and presents as an inflammatory syndrome affecting the skin, GI tract, and liver [11] [10]. It develops in 30-50% of patients receiving transplants from matched related donors [11]. cGvHD, the leading cause of late morbidity, often manifests after 100 days and affects 30-70% of transplant recipients. It presents with heterogeneous, pleomorphic symptoms resembling autoimmune disorders, characterized by tissue inflammation and fibrosis that can lead to permanent organ dysfunction [11].

Host-versus-Graft Reaction (HVGR)

In contrast to GvHD, HVGR occurs when the recipient's immune system recognizes the donor cells as foreign and mounts an immune response to eliminate them [8]. This reaction is primarily mediated by host T cells that remain following lymphodepleting conditioning regimens, as well as host NK cells and antibodies that recognize donor HLA molecules [8]. The consequence of HVGR is rapid clearance of the allogeneic cell therapy, significantly limiting its persistence and therapeutic efficacy in vivo. This presents a major barrier to achieving the long-term durable responses observed with autologous therapies [8].

The Paradox of Autologous GvHD

While GvHD is typically associated with allogeneic transplantation, a clinically and histologically similar syndrome can rarely occur following autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-HCT), with an incidence of approximately 5-20% [12] [13]. The pathophysiology of autologous GvHD (auto-GvHD) is distinct and believed to involve disrupted thymic-dependent immune reconstitution and a failure to reestablish peripheral self-tolerance, leading to an "auto-aggression" syndrome [12]. This condition most commonly affects the skin and is frequently associated with multiple myeloma and specific induction therapies like bortezomib, which may induce apoptosis and break self-tolerance [13]. Auto-GvHD is often self-limited or responsive to corticosteroids, though severe, steroid-refractory cases have been reported [12] [13].

Experimental Models and Assessment Methodologies

In Vitro Assays for Evaluating Alloreactivity

Table 2: Key In Vitro Assays for GvHD and Alloreactivity Assessment

| Assay/Model | Experimental Setup | Key Readouts | Application in Therapy Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) | Co-culture of effector lymphocytes with gamma-irradiated stimulator PBMCs from a different donor [7] | T cell activation (flow cytometry), IFN-γ secretion (ELISA), proliferation, differentiation markers [7] | Measures the potential of donor cells to mount alloreactive response against host antigens; used to validate efficacy of TCR knockout [7] |

| Organoid & 3D Tissue Models | Intestinal or colonic organoids derived from pluripotent stem cells or tissue-resident stem cells exposed to donor immune cells [7] | Epithelial damage, apoptosis, cytokine profiles, gene expression changes [7] | Provides a more physiologically relevant platform to study tissue-specific GvHD pathogenesis and test protective interventions [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for GvHD and Alloreactivity Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Source of effector and stimulator cells for MLR assays; used to establish alloreactive potential [7] |

| ELISA Kits (e.g., IFN-γ) | Quantification of pro-inflammatory cytokine release in MLR co-cultures as a measure of T cell activation [7] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Analysis of T cell activation markers (CD69, CD25), differentiation subsets, and intracellular cytokines [7] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems (e.g., for TRAC) | Genetic disruption of TCRαβ to eliminate alloreactivity while preserving CAR-mediated antitumor function [7] [8] |

| Intestinal Organoid Culture Systems | Modeling human GI tract GvHD in a physiologically relevant ex vivo system for pathogenesis studies [7] |

The experimental workflow for evaluating alloreactivity integrates these tools and models, as shown below:

Mitigation Strategies and Clinical Translation

Engineered Solutions for Allogeneic Cell Therapies

The primary strategy for mitigating GvHD in allogeneic cell products involves genetic disruption of the T-cell receptor (TCR). Since the TCRαβ complex is the primary mediator of alloreactivity, its elimination prevents donor T cells from recognizing host antigens while preserving CAR-mediated antitumor activity [7] [8]. The most efficient approach involves knocking out the T cell receptor Alpha Constant (TRAC) gene using genome-editing technologies like CRISPR/Cas9 or TALENs [7] [8]. This is often combined with magnetic bead depletion to remove any residual TCRαβ+ cells, further reducing alloreactive potential [8]. Alternative approaches include using virus-specific T cells or inherently alloreactive cell types like CAR-NK cells or double-negative T cells (DNTs; CD3+ CD4- CD8-), which have demonstrated potent graft-versus-leukemia effects with minimal GvHD in clinical studies [8].

To address HVGR, strategies include matching donor and recipient HLA profiles and additional genetic engineering of donor cells to reduce their immunogenicity, such as knocking out HLA class I and II molecules [8]. However, these modifications must be balanced against potential impacts on cell persistence and function, as complete TCR ablation has been associated with diminished T cell survival and functional exhaustion upon repeated antigen stimulation [8].

Pharmacological and Cellular Approaches

Pharmacological prophylaxis remains a cornerstone for GvHD prevention, particularly in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The standard backbone includes calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus) combined with methotrexate [11]. Newer agents like the selective T cell co-stimulation modulator Abatacept have also been approved for aGvHD prophylaxis [11]. For established GvHD, high-dose corticosteroids are first-line treatment, though 40% of patients develop steroid-refractory disease with a poor prognosis [11]. Novel therapeutic options for steroid-refractory GvHD include ruxolitinib (JAK1/2 inhibitor), ibrutinib (BTK inhibitor), and belumosudil (ROCK2 inhibitor) [11].

Advanced cellular therapies are also emerging as promising interventions. Decidua stromal cells (DSCs) have shown improved effectiveness over mesenchymal stromal cells in severe aGvHD, with one study reporting a one-year survival rate of 76% in albumin-supplemented DSC-treated patients compared to 20% in the control group [11].

Clinical Trial Outcomes: Autologous vs. Allogeneic

Table 4: Comparative Clinical Outcomes of Autologous and Allogeneic CAR-T Therapies

| Therapy Characteristic | Autologous CAR-T | Allogeneic CAR-T |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Time | Several weeks, leading to treatment delays [7] [4] | Immediate availability ("off-the-shelf"); median 2 days from enrollment to treatment [9] |

| GvHD Risk | Minimal to none (self-tolerance maintained) [4] | Significant risk without mitigation; effectively prevented with TCR knockout [7] [9] |

| Persistence | Potential for long-term persistence (months to years) [7] [4] | May be limited by host immune rejection (HVGR) [8] |

| Clinical Efficacy (LBCL) | High ORR and CR rates in R/R disease [7] | Comparable ORR (67%) and CR (58%) with selected regimen; durable responses observed (median DOR 23.1 months in CR patients) [9] |

| Key Limitations | Product variability, manufacturing failures, T cell exhaustion [7] [8] | Requires genetic engineering, risk of HVGR, potential functional exhaustion with complete TCR ablation [7] [8] |

Recent clinical trials of allogeneic CAR-T products demonstrate promising efficacy and safety. The ALPHA/ALPHA2 trials of cemacabtagene ansegedleucel (cema-cel), an allogeneic anti-CD19 CAR-T product, reported no GvHD across 87 treated patients, confirming the efficacy of TCR knockout strategies [9]. The overall response and complete response rates of 67% and 58%, respectively, with a median duration of response of 23.1 months in complete responders, demonstrate that allogeneic CAR-T cells can induce durable remissions comparable to approved autologous products [9].

The immunological divide between autologous and allogeneic cell therapies is fundamentally defined by the reciprocal threats of GvHD and HVGR. Allogeneic therapies offer substantial practical advantages in scalability and immediate availability but require sophisticated engineering to overcome immunological barriers. Autologous therapies provide a more physiologically compatible option but face limitations in manufacturing and reliability.

Current evidence suggests that genetic engineering approaches, particularly TCR knockout, effectively mitigate GvHD risk in allogeneic products, enabling efficacy comparable to autologous therapies. The emerging clinical data, demonstrating durable responses without GvHD in allogeneic CAR-T trials, signals a promising future for "off-the-shelf" cell therapies. Further research addressing HVGR and enhancing the persistence of allogeneic cells will be crucial to fully realizing the potential of universally accessible cell-based immunotherapies.

The choice of cell source is a foundational decision in biomedical research and therapy development, with significant implications for experimental outcomes and therapeutic efficacy. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three critical cell sources: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs), Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB), and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs). Framed within the broader context of autologous (patient-specific) versus allogeneic (donor-derived) therapy models, this comparison synthesizes collection methodologies, expansion capabilities, and key performance data to inform selection for research and drug development applications.

The distinction between autologous and allogeneic therapies is a central thesis in modern cell therapy research. Autologous therapies use a patient's own cells, minimizing risks of immune rejection but often involving complex, personalized manufacturing processes [4] [1]. Allogeneic therapies use cells from a healthy donor, enabling "off-the-shelf" availability but requiring careful donor-recipient matching and often immunosuppression to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [4] [14].

Within this framework, PBMCs are typically used in an autologous context, UCB is an allogeneic source, and iPSCs can be leveraged for both autologous and allogeneic applications [4] [15]. The following sections provide a detailed, data-driven comparison to guide their use.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each cell source, providing a high-level overview for researchers.

| Feature | PBMCs (Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells) | Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source & Collection | Collected from peripheral blood via apheresis; minimally invasive [16]. | Collected from umbilical vein post-delivery; non-invasive for donor [17]. | Reprogrammed from somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts, urinary epithelial cells) [18] [15]. |

| Primary Cell Types | Lymphocytes (T-cells, B-cells, NK cells), Monocytes [16]. | Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Endothelial Progenitors [17]. | Pluripotent cells capable of differentiation into any somatic cell type [15]. |

| Proliferation & Expansion Potential | Limited ex vivo expansion; short half-life [4] [16]. | High proliferative capacity; UCB HSCs expand significantly better than PB HSCs [16] [17]. | Virtually unlimited self-renewal capacity [18] [15]. |

| Key Advantages | Readily available from adults; ideal for immunology studies [16]. | Immunologically immature (less stringent HLA matching); high angiogenic potential [17]. | Unlimited source; enables autologous therapies; models human diseases in vitro [18] [15]. |

| Major Challenges | Cellular senescence in culture; donor health/age affects quality [4]. | Limited cell volume per unit; finite resource requiring banking [17]. | Risk of genomic instability during reprogramming; complex differentiation protocols [18] [15]. |

Quantitative Performance Data in Applied Research

The selection of a cell source directly impacts experimental outcomes. The following table consolidates quantitative data from key studies comparing these sources in specific applications, such as hematopoietic differentiation and stem cell therapy.

| Performance Metric | PBMCs | Umbilical Cord Blood | iPSCs | Experimental Context & Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSC Proliferation | Baseline (Reference) | Significantly higher (P < 0.0001) | Not Applicable | Expansion of isolated hematopoietic stem cells in vitro [16]. |

| Megakaryocyte Differentiation (CD42b+/CD41+) | 44% ± 9% | 76% ± 11% (P < 0.0001) | Not Applicable | Differentiation efficiency from HSCs to megakaryocytes [16]. |

| Platelet Production Yield | 7.4 PLP*/input cell | 4.2 PLP*/input cell (P = 0.02) | Not Applicable | Yield of platelet-like particles (PLP) under shear flow conditions [16]. |

| Therapeutic Persistence | Limited (Autologous) | Limited (Allogeneic) | High (Maintained characteristics at passage 15) | Long-term culture stability; iPSC-derived MSCs maintained markers vs. UCB-MSCs which started to lose them [18]. |

| Wound Healing/Migration | Variable | Lower | Superior | Migration assay of iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) vs. UCB-MSCs [18]. |

| Immunogenicity Risk | Low (Autologous) | Moderate (Allogeneic, but immune-privileged) | Low (if autologous) to Moderate (if allogeneic) | Risk of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) or immune rejection [4]. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

iPSC Generation and Differentiation into MSCs

This protocol, adapted from a 2021 study, details the non-viral generation of iPSCs from urinary epithelial cells and their subsequent differentiation into mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (iMSCs) [18].

- Cell Source and Culture: Urinary epithelial (UE) cells are isolated from 150-200 mL of human urine via centrifugation. The cell pellet is cultured in DMEM complete medium with 15% FBS [18].

- Non-Viral Reprogramming: At ~80% confluence, UE cells are transfected with mRNA encoding the reprogramming factors (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, KLF4, MYC, LIN28) along with a cocktail of microRNAs using a lipofection agent. This process is repeated for 10 days [18].

- iPSC Colony Selection: From day 9, granulated iPSC colonies appear. Colonies are selected based on TRA1-60 live staining, manually picked, and expanded on Matrigel-coated plates in NutriStem (NS) medium [18].

- Differentiation into iMSCs: Established iPSCs are directed to differentiate into iMSCs using specific culture conditions. The resulting iMSCs are characterized by:

- Trilineage Differentiation: Capacity to form osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes is confirmed.

- Surface Marker Expression: High expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105 is verified via qRT-PCR and Western blot [18].

Haematopoietic Stem Cell Isolation and Megakaryocyte Culture

This protocol, used for comparing UCB and PB-derived HSCs, focuses on in vitro platelet production [16].

- HSC Isolation:

- UCB: CD34+ cells are isolated using immunomagnetic cell sorting. Red blood cells are first lysed, and mononuclear cells are separated via density-gradient centrifugation with ficoll before the magnetic selection [16].

- PB (Buffy Coats): Buffy coats from donated blood are pooled. A similar immunomagnetic sorting is used, but with adjusted bead-to-cell ratios and additional washing steps due to the lower frequency of HSCs in peripheral blood [16].

- Cell Culture and Differentiation:

- Isolated CD34+ cells are cultured in HP01 medium supplemented with thrombopoietin (TPO), stem cell factor (SCF), and interleukin-3 (IL-3) for 6 days for expansion.

- On day 7, cells are switched to a differentiation medium containing TPO and SCF to direct them towards megakaryocytes.

- On day 12, megakaryocytes are harvested and separated from small particles via a BSA gradient centrifugation [16].

- In Vitro Platelet Production:

- Differentiated megakaryocytes are perfused through custom-built microfluidic flow chambers coated with von Willebrand factor (VWF) under controlled shear stress to mimic physiological platelet release [16].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

iPSC Generation and Differentiation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the key steps involved in creating and differentiating iPSCs, as described in the experimental protocol.

Autologous vs. Allogeneic Cell Therapy Pathways

This diagram outlines the fundamental logistical differences between autologous and allogeneic therapy development, highlighting where PBMCs, UCB, and iPSCs are utilized.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and their functions for working with these cell sources, based on the cited methodologies [18] [16].

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Cell Source Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque | Density gradient medium for isolation of mononuclear cells (PBMCs, UCB-MNCs) from whole blood or cord blood. | PBMCs, UCB [16] |

| Immunomagnetic CD34+ Beads | Positive selection and isolation of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from heterogeneous cell populations. | UCB, PB (from Buffy Coats) [16] |

| Reprogramming Factor mRNAs | Non-viral induction of pluripotency in somatic cells (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC). | iPSCs [18] |

| Lipofectamine Transfection Agent | Delivery of mRNA reprogramming factors into somatic cells. | iPSCs [18] |

| Thrombopoietin (TPO) & Stem Cell Factor (SCF) | Critical cytokines for the expansion and differentiation of HSCs into megakaryocytes. | UCB, PBMCs (for Platelet Production) [16] |

| Matrigel / iMatrix | Basement membrane matrix for coating culture vessels to support pluripotent stem cell attachment and growth. | iPSCs [18] |

| NutriStem (NS) Medium | Xeno-free, defined culture medium optimized for the maintenance of pluripotent stem cells. | iPSCs [18] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD34, CD42b, CD41, CD73, CD90, CD105) | Characterization of cell surface markers to identify, quantify, and purify specific cell populations. | All (for HSCs, Megakaryocytes, MSCs) [18] [16] |

The field of advanced therapeutics is increasingly defined by a fundamental distinction between two cellular sourcing strategies: autologous and allogeneic cell therapies. Autologous cell therapy involves the extraction, manipulation, and reinfusion of a patient's own cells, creating a perfectly matched biological product [1] [4]. This approach forms the foundation of current CAR-T (Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell) treatments for hematological malignancies, where a patient's T-cells are genetically engineered to target cancer cells [1] [2]. In contrast, allogeneic cell therapy utilizes cells from a healthy donor,

which can be manufactured in large batches, cryopreserved, and made readily available as an "off-the-shelf" treatment for multiple patients [1] [19] [20]. This paradigm encompasses a range of platforms, including donor-derived CAR-T cells, CAR-NK (Natural Killer) cells from cord blood or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapies [3] [20].

The choice between these models represents a critical strategic decision in therapy development, balancing the personalized immunological safety of autologous products against the scalable, accessible nature of allogeneic therapies. This comparison guide examines the inherent advantages of each approach within the broader context of efficacy research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed, data-driven analysis to inform platform selection and development pathways.

Comparative Advantage Analysis: Core Characteristics

The following analysis synthesizes key performance indicators and characteristics of autologous versus allogeneic cell therapies, drawing from current clinical trends and manufacturing data.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Performance Indicators of Autologous vs. Allogeneic Cell Therapies

| Characteristic | Autologous Therapy | Allogeneic Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | Patient's own cells [1] [4] | Healthy donor (related or unrelated) [1] [20] |

| Immunological Compatibility | Inherently compatible; minimal rejection risk [1] [2] | Requires HLA matching/engineering; risk of GvHD and immune-mediated clearance [1] [4] [21] |

| Typical Manufacturing Time | Several weeks [2] [21] | Batch-produced in advance; "off-the-shelf" [19] [20] |

| Scalability | Limited; scale-out for individual patients [1] | High; scale-up for mass production [1] [19] |

| Cost Structure | High-cost, service-based model [1] [4] | Potential for lower cost per dose due to economies of scale [1] [19] |

| Product Consistency | Variable; depends on patient's cell health and prior treatments [19] [4] [21] | High; standardized batches from healthy donors [19] [21] |

| Clinical Trial Dominance (China 2014-2024) | T cells: 51.4% of 206 trials [22] | Emerging area within the T-cell and stem cell trial landscape [3] [22] |

Table 2: Analysis of Key Therapeutic Applications and Targets (Based on Clinical Trial Data from China, 2014-2024)

| Therapy/Disease Area | Prominent Cell Types | Common Targets | Trial Phase Distribution (n=206) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphoma (Top Indication) | T cells (e.g., CAR-T) [22] | CD19 (54.9% of targeted trials) [22] | Phase I: 64.1% (132 trials) [22] |

| Leukemia | T cells, Hematopoietic Stem Cells [22] [20] | CD19, BCMA (9.9%) [22] | Phase II: 32.5% (67 trials) [22] |

| Inflammatory/Autoimmune Diseases | Stem Cells (e.g., MSCs) [22] [20] | N/A (Immunomodulatory) | Phase III: 3.4% (7 trials) [22] |

The Autologous Advantage: Personalized Immunological Safety

Mechanism of Immunological Compatibility

The principal advantage of autologous cell therapy lies in its inherent immunological safety profile. Because the therapeutic cells are derived from the patient's own body, they express the patient's unique human leukocyte antigen (HLA) profile [2]. This self-recognition prevents the host immune system from identifying the infused cells as foreign, thereby eliminating the risk of immune rejection and the life-threatening complications of Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) [1] [4] [2]. In GvHD, immune cells from the donor (the graft) mount an attack on the patient's (the host) tissues, which can manifest as acute or chronic inflammatory conditions affecting the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract [4]. The autologous framework naturally circumvents this risk, creating a biologically closed system.

Consequently, patients receiving autologous therapies typically do not require concurrent immunosuppressive regimens [4] [2]. This is a significant clinical advantage, as immunosuppressive drugs carry their own risks, including increased susceptibility to infections, kidney and liver toxicity, metabolic disturbances, and hypertension [4]. The absence of this pharmacological burden allows the engineered cells to proliferate and persist in the patient's body for months or even years, potentially eliciting durable long-term therapeutic responses, which is a hallmark of successful CAR-T therapies in hematological malignancies [4].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol for Autologous CAR-T Generation

The production of autologous cell therapies is a complex, patient-specific workflow that demands rigorous chain-of-identity management and precision. The following diagram and protocol detail the standard methodology for generating autologous CAR-T cells, a cornerstone of the approach.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Autologous CAR-T Cell Manufacturing

Leukapheresis and Shipment: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are collected from the cancer patient via leukapheresis. The apheresis material is shipped cryopreserved or fresh under strict temperature-controlled conditions (typically 4-10°C) to a centralized Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) facility [1].

T-cell Activation: Upon receipt, T-cells are isolated from the PBMCs using density gradient centrifugation or magnetic bead-based separation (e.g., CD3/CD28 bead selection). The isolated T-cells are then activated ex vivo using antibodies against CD3 and CD28, often conjugated to the magnetic beads, in the presence of specific cytokines like IL-2 [21].

Genetic Modification via Viral Transduction: The activated T-cells are genetically engineered to express the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). This is most commonly achieved through lentiviral or retroviral vector transduction [22]. The viral vector, containing the CAR transgene, is introduced to the activated T-cells in the presence of enhancers like polybrene or protamine sulfate to increase transduction efficiency. The CAR construct is typically designed to target a specific tumor antigen (e.g., CD19, BCMA) and contains intracellular signaling domains (e.g., CD3ζ, 4-1BB, CD28) for T-cell activation [22] [21].

Ex Vivo Expansion: The transduced T-cells are cultured in a bioreactor system for a period of 7-10 days to expand their numbers to a clinically relevant dose (often in the range of 10^8 to 10^9 cells). This is performed in xeno-free, serum-free cell culture media formulated to support T-cell growth and maintain a favorable phenotype (e.g., less differentiated, memory-like T-cells which are associated with better persistence in vivo) [21]. The use of closed-system bioreactors minimizes contamination risk and supports reproducibility [19] [21].

Formulation, Cryopreservation, and Release Testing: The expanded CAR-T cell product is washed, formulated in a final infusion bag with cryoprotectant (e.g., DMSO), and cryopreserved in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen. A sample is taken for rigorous Quality Control (QC) release testing, which includes assessments of sterility (bacterial/fungal culture, mycoplasma), viability, cell count and identity, CAR expression (e.g., by flow cytometry), vector copy number, and potency (e.g., in vitro tumor cell killing assay) [1].

Patient Infusion and Monitoring: The cryopreserved product is shipped back to the treatment center, thawed, and infused into the patient after a brief course of lymphodepleting chemotherapy (e.g., fludarabine/cyclophosphamide). Patients are closely monitored for both efficacy and acute toxicities, primarily Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) and Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS) [2].

The Allogeneic Advantage: Off-the-Shelf Scalability

Mechanisms for Scalable and Accessible Therapeutics

The allogeneic model transforms cell therapy from a bespoke service into a standardized, distributable drug product. Its scalability advantage is multi-faceted, rooted in manufacturing, logistics, and economic principles. By sourcing cells from a single, healthy donor, manufacturers can create a master cell bank (MCB) that serves as a renewable, consistent starting material for thousands of therapeutic doses [19] [20]. This enables mass production in large-scale bioreactors, moving away from the single-patient lots that characterize autologous production [1] [19]. This scale-up strategy, akin to the production of monoclonal antibodies, leverages economies of scale to significantly reduce the cost per dose, making the therapy more financially sustainable for healthcare systems [1] [19].

The "off-the-shelf" nature of these products is perhaps their most transformative characteristic. Unlike autologous therapies, which involve a weeks-long "vein-to-vein" time, allogeneic products are cryopreserved and stored until needed, allowing for immediate treatment upon diagnosis [19] [4]. This is particularly critical for patients with aggressive diseases who cannot endure the wait associated with personalized manufacturing. Furthermore, this model decouples production from the patient, enabling centralized manufacturing hubs to supply a global network of treatment centers, thereby dramatically improving geographic accessibility and helping to overcome "CGT deserts" where advanced therapies are unavailable [19] [23].

Genetic Engineering Workflow for Universal Allogeneic Cells

A key technological enabler for allogeneic therapies is advanced gene editing, which is used to overcome the inherent immunological hurdles of using donor cells. The following diagram and protocol describe the creation of "universal" allogeneic CAR-T cells, a leading platform in the field.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Generating Universal Allogeneic CAR-T Cells

Donor Screening and T-cell Collection: A healthy donor undergoes rigorous screening for pathogens and communicable diseases. T-cells are collected via leukapheresis. These cells, being treatment-naive and robust, often demonstrate superior expansion and engineering potential compared to cells from pre-treated patients [19] [21].

Gene Editing to Ablate Endogenous T-cell Receptor (TCR): A critical step to prevent GvHD is the knockout of the endogenous αβ T-cell receptor (TCR). This is achieved using gene-editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 or TALEN [19] [21]. Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes of Cas9 protein and guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the constant regions of the TCRα or TCRβ chain are delivered into the donor T-cells via electroporation. This disruption prevents the donor T-cells from recognizing and attacking the recipient's healthy tissues.

Gene Editing to Evade Host Immune Rejection: To mitigate the risk of the recipient's immune system rejecting the donor cells, HLA class I molecules are often knocked out using similar gene-editing techniques [20]. This makes the donor cells "invisible" to the host's CD8+ T-cells. Some strategies also target HLA class II to avoid CD4+ T-cell mediated rejection. An emerging alternative is the engineering of "hypoimmune" cells from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are genetically modified to modulate immune recognition pathways [24] [2].

Introduction of the Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR): The gene-edited T-cells are then engineered to express the CAR, typically via lentiviral vector transduction [3]. This step is analogous to the autologous process but is performed on a much larger scale, using bioreactors capable of producing a single batch for hundreds of patients [19].

Purification and Expansion: Following gene editing and CAR transduction, a purification step (e.g., using magnetic bead-based selection for the CAR+ population) is often employed to remove any remaining unedited or non-transduced cells, ensuring a pure and safe final product [21]. The purified CAR-T cells undergo large-scale expansion in bioreactors to generate a master cell bank, which is then used to create working cell banks for clinical production.

Quality Control, Cryopreservation, and Distribution: The final universal CAR-T cell product undergoes comprehensive QC testing, including checks for editing efficiency (e.g., via next-generation sequencing to confirm TCR knockout), CAR expression, sterility, and potency. The product is then cryopreserved in individual patient doses, creating an inventory of "off-the-shelf" therapies that can be distributed globally and administered on demand [19] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and manufacturing of both autologous and allogeneic cell therapies rely on a sophisticated suite of reagents, instruments, and platforms. The table below details key solutions essential for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Therapy Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Serum-Free Cell Culture Media | Formulated for ex vivo T-cell/NK cell expansion [21]. | Xeno-free composition critical for regulatory compliance; formulations impact T-cell phenotype and yield [21]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 or TALEN Systems | Gene-editing tools for TCR and HLA knockout in allogeneic therapies [19] [21]. | High editing efficiency and specificity; delivery via electroporation (RNP complexes preferred) [21]. |

| Lentiviral/Viral Vectors | Delivery of CAR transgene into target cells [22]. | High titer and transduction efficiency; safety testing for replication-competent viruses [22]. |

| Magnetic Bead Separation Kits | Isolation of specific immune cells (e.g., CD3+ T-cells); purification of CAR+ populations [21]. | Closed-system automation compatibility; high purity and cell viability post-selection [1] [21]. |

| Closed-System Bioreactors | Automated, scalable expansion of cells [19] [21]. | Minimizes contamination risk; enables process control and monitoring; essential for scale-up [19] [21]. |

| iPSC Lines | Source for deriving "off-the-shelf" NK cells, T-cells, and other therapeutic cell types [3] [24]. | Clonal origin ensures consistency; requires robust differentiation protocols [24]. |

The dichotomy between autologous and allogeneic cell therapies presents the field with two powerful, yet fundamentally different, paths forward. The autologous approach leverages the body's own biological machinery to create a perfectly matched therapy, prioritizing personalized immunological safety and demonstrating remarkable efficacy, particularly in oncology, without the need for immunosuppression [1] [2]. Conversely, the allogeneic model embraces industrialization, utilizing advanced gene editing and manufacturing technologies to create standardized, off-the-shelf products that promise greater scalability, accessibility, and potential cost-effectiveness [3] [19].

The future of cell therapy will not be dominated by one approach over the other, but rather will see the coexistence and refinement of both paradigms. Autologous therapies will likely remain the gold standard for certain indications where cell quality from pre-treated patients is less concerning or where long-term persistence is paramount. Allogeneic therapies are poised to expand the reach of cell therapy to larger patient populations and into new disease areas, including autoimmune disorders and solid tumors, provided the challenges of immune rejection and long-term engraftment are fully overcome [3] [23]. For researchers and drug developers, the strategic choice between these platforms will continue to depend on a balanced consideration of the target disease, patient population, manufacturing capabilities, and the ultimate goal of delivering transformative treatments to those in need.

From Bench to Bedside: Clinical Platforms and Therapeutic Applications

The field of cellular immunotherapy has been fundamentally shaped by the distinction between autologous (patient-derived) and allogeneic (donor-derived) approaches. Autologous therapies, such as most approved CAR-T cells, leverage the patient's own cells, minimizing risks of immune rejection and graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [2] [4]. However, they face challenges related to manufacturing complexity, high costs, and variable cell quality due to a patient's disease state or prior treatments, which can lead to significant treatment delays [2] [4]. In contrast, allogeneic therapies, derived from healthy donors, offer the potential for "off-the-shelf" availability, shorter manufacturing times, lower costs, and more consistent product quality [3] [25] [26]. Their primary challenges include the risk of host immune rejection and GvHD, which are being addressed through genetic engineering strategies like TCR knockout [4] [26]. This framework of autologous versus allogeneic sourcing is a critical lens for evaluating the performance, applications, and future development of CAR-T, CAR-NK, TCR-T, and Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) therapy platforms.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Clinical Platforms

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Leading Cellular Immunotherapy Platforms

| Therapy Platform | Key Mechanism of Action | Primary Clinical Applications | Autologous vs. Allogeneic Feasibility | Key Advantages | Major Challenges & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR-T | Engineered T cells target surface antigens independently of MHC [27] [28]. | Hematological malignancies (B-cell lymphomas, leukemias) [25] [28]. | Primarily Autologous; Allogeneic in development [2] [26]. | High efficacy in B-cell malignancies; potential for long-term persistence [25] [4]. | CRS/ICANS toxicity; antigen escape; limited efficacy in solid tumors [27] [28]. |

| CAR-NK | Engineered NK cells target antigens, leveraging innate cytotoxicity [28] [5]. | Hematological malignancies, emerging data in autoimmunity (e.g., SLE) [5] [26]. | Primarily Allogeneic ("off-the-shelf") [5] [26]. | Favorable safety profile (low CRS/ICANS, no GvHD); "off-the-shelf" availability [25] [5]. | Shorter in vivo persistence; complex large-scale manufacturing [28] [26]. |

| TCR-T | Engineered T cells target intracellular antigens via MHC presentation [27]. | Solid tumors, viral-associated cancers (limited data in results). | Primarily Autologous. | Can target a broader range of antigens, including intracellular targets. | MHC-restricted; requires high-affinity TCR identification; risk of on-target/off-tumor toxicity. |

| CAR-MSC | Combines CAR targeting with MSC's immunomodulatory & tropic functions [27]. | Cancer (e.g., GBM, sarcoma), GvHD, inflammatory disorders [27]. | Primarily Allogeneic [27] [29]. | Dual targeting/immunomodulation; low immunogenicity; tissue homing [27] [30]. | Heterogeneous cell sources; limited persistence; scalability and manufacturing hurdles [27] [29]. |

Table 2: Summary of Key Efficacy and Safety Outcomes from Clinical Studies

| Therapy Platform | Disease Context | Best Overall Response Rate (ORR) | Best Complete Response Rate (CRR) | Key Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allogeneic CAR-T & CAR-NK [25] [26] | Relapsed/Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma (LBCL) | 52.5% (95% CI, 41.0-63.9) [25] [26] | 32.8% (95% CI, 24.2-42.0) [25] [26] | Very low severe CRS (0.04%) & ICANS (0.64%); only one GvHD case in 334 patients [25] [26]. |

| Allogeneic CD19 CAR-NK [5] | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | 6 of 9 (67%) patients achieved remission at >12 months [5]. | Not Applicable | Only 1 of 18 patients had grade 1 CRS; no neurotoxicity or severe adverse events [5]. |

| CAR-T (CD123-targeted) [28] | Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | Complete Remission (CR) rates of 50-66% [28]. | Not Specified | Manageable Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Manufacturing of Allogeneic "Off-the-Shelf" CAR-NK Cells

This protocol outlines the production of allogeneic CAR-NK cells from cord blood, a common source for clinical applications [26].

- Cell Sourcing and Isolation: Obtain umbilical cord blood units from healthy donors under informed consent. Isolate mononuclear cells using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque). NK cells are then positively selected using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with anti-CD56 beads [26].

- Genetic Modification (CAR Transduction): Activate isolated NK cells with IL-2 and IL-15. Transduce the cells with a replication-incompetent lentiviral vector encoding the CAR construct (e.g., anti-CD19 scFv, CD8 hinge/transmembrane, and 4-1BB/CD3ζ signaling domains). A critical enhancement is the inclusion of a gene for autocrine IL-15 in the vector to support cell survival and persistence in vivo [26].

- In Vitro Expansion: Culture the transduced cells in a GMP-compliant bioreactor system using a medium supplemented with cytokines. Monitor cell density, viability, and CAR expression percentage over 2-3 weeks.

- Quality Control and Formulation: Perform rigorous quality control assays, including flow cytometry for CAR expression and CD56+ purity, sterility testing (mycoplasma, endotoxin), and potency assays (e.g., cytotoxicity against target cell lines). The final product is cryopreserved in infusion bags, creating an "off-the-shelf" inventory [26].

Protocol 2: Clinical Workflow for Allogeneic CAR Therapy in Lymphoma

This protocol describes the patient journey in a clinical trial for allogeneic CAR-T or CAR-NK therapy for relapsed/refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma [25] [26].

- Patient Lymphodepletion: The patient receives a lymphodepleting conditioning regimen, typically consisting of fludarabine (25 mg/m² per day) and cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m² per day), administered daily for three days (e.g., from days -5 to -3 relative to infusion) [5] [26]. This step is crucial to create a favorable environment for the engraftment and expansion of the donor cells.

- Product Thaw and Infusion: On the designated treatment day (Day 0), a cryopreserved vial of the allogeneic CAR-T or CAR-NK cell product is thawed at the patient's bedside. The cells are administered via intravenous infusion without further manipulation [26].

- Toxicity Monitoring and Management: Patients are closely monitored for adverse events, primarily Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) and Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS), using standardized grading systems (ASTCT criteria). Supportive care, including the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab for CRS, is administered as needed [25].

- Efficacy Assessment: Response to treatment is evaluated according to the Lugano classification. Tumor burden is assessed via PET-CT scans at predefined intervals (e.g., at 1, 3, and 6 months post-infusion) to determine objective response rates (ORR) and complete response rates (CRR) [25] [26].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

CAR-T Cell Activation and Intracellular Signaling

Diagram 1: CAR-T cell activation signaling pathway. This diagram illustrates the intracellular signaling cascade following CAR engagement with its target antigen, leading to T-cell activation, proliferation, and execution of cytotoxic functions [28].

Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Mediated Immunomodulation

Diagram 2: MSC immunomodulation and CAR-MSC targeting. This diagram shows how MSCs modulate the immune environment via paracrine factors and how engineering them with CARs (creating CAR-MSCs) directs this activity to specific disease sites like tumors [27] [29] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Cell Therapy Research

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation & Selection | Anti-CD3/CD28 beads (T cells), Anti-CD56 beads (NK cells), Ficoll-Paque [26]. | Isolation and activation of specific immune cell subsets from donor apheresis or tissue samples. |

| Genetic Engineering | Lentiviral / Retroviral vectors, CRISPR-Cas9 systems, mRNA for transient expression [27] [28] [26]. | Stable or transient introduction of CAR constructs or genetic modifications (e.g., TCR knockout). |

| Cell Culture & Expansion | GMP-grade IL-2, IL-15, serum-free media, large-scale bioreactors [26]. | Ex vivo expansion of engineered cells to clinical doses while maintaining phenotype and function. |

| Characterization & QC | Flow cytometry antibodies (CD3, CD56, CD105, CD73, CD90), cytotoxicity assays (Incucyte, LDH) [29] [30]. | Confirmation of cell identity, purity, CAR expression, and pre-infusion potency. |

| In Vivo Modeling | NSG (NOD-scid-gamma) mice, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models [27]. | Preclinical evaluation of therapy efficacy, persistence, and safety in an in vivo system. |

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies. By genetically engineering a patient's or donor's T cells to express a synthetic receptor targeting CD19—a surface antigen consistently expressed on B-cell lymphomas and leukemias—this modality redirects the immune system to eradicate malignant cells. The therapeutic landscape is divided into two primary manufacturing approaches: autologous CAR-Ts, which use a patient's own T cells, and allogeneic CAR-Ts, which use T cells from healthy donors to create "off-the-shelf" products. Autologous CD19-targeting CAR-Ts like axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel have demonstrated remarkable efficacy, establishing a new standard of care. However, challenges including manufacturing delays, product variability, and access limitations have spurred the development of allogeneic alternatives. This guide provides a systematic, data-driven comparison of the efficacy, safety, and underlying experimental data for these platforms, contextualized within the broader thesis of autologous versus allogeneic therapy research.

Efficacy and Safety: A Comparative Data Analysis

Direct comparisons of autologous and allogeneic CD19 CAR-T therapies reveal distinct efficacy and safety profiles, influenced by product design and patient factors. The data below summarize key clinical outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of CD19-Targeted CAR-T Therapies

| CAR-T Product / Type | Malignancy | Complete Response (CR) Rate | Overall Survival (OS) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous hCART19 | R/R B-ALL | 93.1% (CR/CRi, n=54/58) | Median OS: 21.5 months | [31] |

| Autologous CD19 CART | R/R DLBCL | Used as study comparator | Inferior median OS vs. dual-target | [32] |

| Dual-Target CD19/20 CART (Prizlon-cel) | R/R DLBCL | Significantly higher CR rate at 3 months | Median OS: 31.8 months longer than CD19 CART | [32] |

| Dual-Target CD19/22 CART | R/R B-ALL & NHL | High CR rates in B-ALL | Improved outcomes in high-risk patients | [33] |

Table 2: Comparative Safety Profile of CD19-Targeted CAR-T Therapies

| Adverse Event | Autologous CD19 CART | Dual-Target CD19/20 CART | Allogeneic CAR-T Considerations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) | Baseline incidence | Significantly higher incidence | Risk varies with gene-editing strategy | [32] |

| Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS) | Reported | Not significantly different | -- | [32] |

| Hematological Toxicity | Reported | Higher incidence | -- | [32] |

| Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) | Not applicable | Not applicable | A key risk requiring TCR ablation | [34] [8] |

| Infections | -- | Higher incidence | -- | [32] |

Key Insights from Clinical Data

- Superiority of Dual-Targeting Strategies: A single-center retrospective analysis of 70 patients with R/R DLBCL demonstrated that dual-target CD19/20 CAR-T (C-CAR039) achieved significantly superior 3-month complete response rates and extended median overall survival by 31.8 months compared to single-target CD19 CAR-T therapy [32].

- Impact of Humanization: A clinical trial with 58 R/R B-ALL patients showed that humanized CD19-targeted CAR-T (hCART19) achieved a 93.1% complete remission rate and was associated with longer event-free survival and B-cell aplasia (up to 616 days) compared to murine-based CAR-Ts, indicating enhanced persistence [31].

- The Allogeneic Challenge: The primary risks for allogeneic "off-the-shelf" products are Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) and host-versus-graft rejection. Mitigation relies on gene-editing technologies (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9, TALEN) to disrupt the T-cell receptor (TCR) complex (e.g., TRAC locus) and sometimes HLA class I molecules [34] [35] [8].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Evaluating CAR-Ts

Clinical Trial Design for Efficacy and Safety

The protocols for evaluating CAR-T therapies in human trials are standardized to ensure rigorous assessment of efficacy and safety.

- Lymphodepletion: Patients uniformly receive a lymphodepleting chemotherapy regimen, typically fludarabine (25 mg/m²/day) and cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m²/day) for three days prior to CAR-T infusion [32] [31].

- Cell Infusion: CAR-T cells are administered intravenously at a dose ranging from 1-5 × 10⁶ cells per kilogram of patient weight [32].

- Response Assessment: Treatment response is evaluated using the Lugano classification (2014) for lymphomas, which relies on PET-CT and CT scans to categorize outcomes as Complete Response (CR), Partial Response (PR), Stable Disease (SD), or Progressive Disease (PD). Response is typically assessed at one and three months post-infusion [32] [36].

- Safety Monitoring: The occurrence and severity of adverse events like CRS and ICANS are graded according to the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) consensus guidelines [32] [37].

- Endpoint Definitions: Key endpoints include Overall Survival (OS), Progression-Free Survival (PFS), and Duration of Response (DOR), calculated from the time of CAR-T cell infusion [32].

In Vitro and In Vivo Preclinical Assessment

Preclinical models are crucial for establishing the potency and anti-tumor activity of novel CAR-T constructs.

- Cytotoxicity Assays: Target cancer cells (e.g., AML cell lines like MOLM-13) are co-cultured with CAR-T cells at various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios. After 24-48 hours, cytotoxicity is calculated based on the percentage of live tumor cells remaining compared to control cultures without effector cells [38].

- In Vivo Xenograft Models: Immunodeficient NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) mice are injected intravenously with patient-derived xenograft (PDX) cells or luciferase-expressing cancer cell lines to establish tumors. CAR-T cells are then administered intravenously, and tumor burden is tracked over time using bioluminescence imaging (Xenogen IVIS system) and analysis software (Living Image) [38].

Signaling Pathways and Engineering Logic

The core architecture of a second-generation CAR, which forms the basis of most approved therapies, integrates multiple signaling domains to achieve robust T-cell activation. The following diagram illustrates the structure and activation logic of a CD19-targeting CAR.

Diagram 1: CD19 CAR-T Activation Logic

The CAR construct is a synthetic protein with three main domains. The extracellular domain contains a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from an anti-CD19 antibody, which is responsible for antigen recognition. This is fused to a transmembrane domain that anchors the receptor to the T-cell membrane. The intracellular signaling domain is typically a second-generation design, combining a primary costimulatory domain (such as CD28 or 4-1BB) with the CD3ζ chain, which contains Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Activation Motifs (ITAMs). Upon binding to CD19, the CAR initiates coordinated signaling through both CD3ζ and the costimulatory domain, leading to full T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytotoxic killing of the target B-cell [39] [33].

Manufacturing Workflows: Autologous vs. Allogeneic

The fundamental difference between autologous and allogeneic CAR-T therapies lies in their manufacturing pipelines and the requisite genetic engineering steps, as illustrated below.

Diagram 2: CAR-T Manufacturing Workflow Comparison

The autologous pathway (yellow nodes) begins with leukapheresis of the patient's own T cells. These cells are then activated, transduced with a viral vector (e.g., lentivirus) encoding the CAR, and expanded ex vivo before being infused back into the patient. This process is patient-specific, minimizes the risk of immunogenic rejection, but is time-consuming and can be hampered by the poor quality of patient-derived T cells [34] [35].

The allogeneic pathway (green nodes) starts with T cells collected from a healthy donor. A critical, additional step (red node) is the use of gene-editing technologies (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9) to knock out the T-cell receptor (TCR) alpha constant (TRAC) locus. This prevents the donor T cells from recognizing the patient's tissues as foreign, thereby mitigating the risk of GvHD. These edited cells are then transduced, expanded, and cryopreserved to create an "off-the-shelf" product that is readily available for multiple patients [34] [35] [8].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CAR-T Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function in CAR-T Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery of CAR transgene into T-cell genome | Stable expression of CD19-targeting CAR in primary T cells [31] |

| Anti-CD3/CD28 Magnetic Beads | Ex vivo T-cell activation and expansion | Stimulating T cells prior to transduction [31] |

| Cytokine ELISA Kits | Quantification of cytokine levels (e.g., IL-6, IFN-γ) | Monitoring CRS potential in CAR-T co-culture supernatants [31] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Analysis of CAR expression and immune phenotyping | Detecting CD19 CAR transduction efficiency via tag detection [38] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Gene editing for allogeneic CAR-T development | Knocking out TRAC to prevent GvHD [34] [8] |

| NSG (NOD-Scid-Gamma) Mice | In vivo assessment of CAR-T efficacy and persistence | Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of AML [38] |

The field of adoptive cell therapy is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from patient-specific autologous treatments towards universally available allogeneic "off-the-shelf" products. While autologous Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapies have demonstrated remarkable success in hematological malignancies, their application in solid tumors and autoimmune diseases faces substantial biological and logistical barriers [40]. Allogeneic approaches, utilizing cells from healthy donors, are emerging as promising alternatives that overcome challenges such as high costs, labor-intensive manufacturing, and lengthy production times [3]. This evolution is particularly critical for solid tumors, which constitute approximately 90% of all human cancers and present unique therapeutic challenges including heterogeneous antigen expression, immunosuppressive microenvironments, and physical barriers to T-cell infiltration [40]. Simultaneously, researchers are exploring engineered cellular therapies for autoimmune conditions, representing a frontier expansion for this technology beyond oncology.

The fundamental distinction between autologous and allogeneic approaches lies in their source material and manufacturing implications. Autologous therapies use the patient's own cells, minimizing immunogenic risks but creating complex logistical challenges and production delays [4]. Allogeneic therapies leverage healthy donor cells, enabling standardized, large-scale manufacturing and immediate product availability [41] [42]. This review systematically compares the performance of these competing platforms in solid tumors and autoimmune diseases, analyzing clinical outcomes, experimental methodologies, and technological innovations that are shaping the future of cellular therapeutics.

Comparative Clinical Trial Outcomes: Solid Tumors

Current Clinical Landscape

Clinical development of allogeneic CAR-T therapies for solid tumors remains in earlier stages compared to hematological malignancies, though promising early-phase trials are establishing proof-of-concept. NKG2D CAR-T cells targeting stress ligands (MICA/B, ULBP1–6) represent one of the most advanced allogeneic platforms, recognizing antigens expressed on over 80% of diverse solid tumors including pancreatic and ovarian cancers [41]. Preliminary clinical data demonstrate encouraging signals of biological activity despite the formidable barriers presented by the solid tumor microenvironment.

The table below summarizes key clinical findings from allogeneic CAR-T trials in solid tumors:

Table 1: Clinical Outcomes of Allogeneic CAR-T Cell Therapy in Solid Tumors

| CAR Target | Tumor Types | Clinical Efficacy | Safety Profile | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NKG2D [41] | Pancreatic, ovarian, and other solid malignancies | Early evidence of antitumor activity in phase I trials | Manageable toxicity profile; Risks of off-target effects from gene editing | Recognizes stress ligands on >80% of solid tumors; CRISPR-edited to prevent GvHD |

| B7-H3 [40] | Various solid tumors | Preclinical evidence of efficacy | Under evaluation in early clinical trials | An immunomodulatory molecule overexpressed on many solid tumors |

| Mesothelin [40] | Mesothelioma, pancreatic, ovarian | Early clinical development | On-target, off-tumor toxicity concerns | Often combined with safety switches |

Autologous vs. Allogeneic Comparison in Solid Tumors

Direct comparisons between autologous and allogeneic CAR-T approaches in solid tumors are limited by the early stage of clinical development. However, distinct patterns are emerging regarding their respective advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Autologous vs. Allogeneic CAR-T Approaches for Solid Tumors

| Parameter | Autologous CAR-T | Allogeneic CAR-T |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Time | 3+ weeks [42] | Immediate availability from cryopreserved stocks [41] |

| Starting Cell Quality | Often compromised by prior therapies [42] | Optimal from healthy donors [4] |

| T-cell Fitness | Variable; may exhibit exhaustion [42] | Consistent; robust proliferative capacity [41] |

| GvHD Risk | Minimal (self-derived) [4] | Requires TCR disruption via gene editing [41] |