Beyond the Monolayer: How 3D Cell Culture Reshapes Gene Expression for More Predictive Disease Models

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of gene expression profiles in 2D versus 3D cell culture models, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Beyond the Monolayer: How 3D Cell Culture Reshapes Gene Expression for More Predictive Disease Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of gene expression profiles in 2D versus 3D cell culture models, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of how spatial architecture influences genomic regulation, details methodological approaches for establishing 3D cultures, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and validates the superior physiological relevance of 3D models through comparative analysis with in vivo data. The synthesis of current evidence underscores that 3D cultures more accurately recapitulate in vivo-like gene expression, offering transformative potential for drug discovery, personalized medicine, and reducing preclinical attrition rates.

The Genomic Shift: Uncovering the Fundamental Impact of 3D Architecture on Gene Expression

The cellular microenvironment encompasses all the physical, chemical, and biological cues that surround a cell, fundamentally governing its behavior and function. This includes interactions with neighboring cells, signaling molecules, mechanical forces, and the three-dimensional extracellular matrix (ECM) [1] [2]. In vitro modeling of this complex milieu is crucial for advancing our understanding of cell biology, particularly in cancer research and drug development. For decades, traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture has been the standard workhorse in biological research due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness [3] [4]. However, the scientific community increasingly recognizes that cells grown in flat, rigid monolayers exhibit altered morphology, polarity, and gene expression, limiting their physiological relevance [2].

This recognition has driven the shift toward three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models, which aim to bridge the gap between conventional 2D cultures and in vivo conditions [1] [5]. By allowing cells to grow and interact in all three dimensions, these models better recapitulate the architectural and functional complexities of living tissues [4]. The transition from 2D to 3D is not merely a technical improvement but a paradigm shift that more accurately mimics the dynamic cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions within the native tumor microenvironment (TME), thereby offering more predictive insights for clinical translation [5]. This guide provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparison of these two systems, with a particular focus on their implications for gene expression research.

Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D Culture Systems

The core distinction between these models lies in their spatial geometry, which fundamentally shapes the cellular experience. In 2D cultures, cells are forced to adopt unnatural, flattened morphologies as they adhere to a rigid plastic or glass surface [4]. This disrupts normal cell polarity and creates uniform, often unlimited, access to nutrients, oxygen, and therapeutic agents [6] [2]. In contrast, 3D cultures enable cells to assemble into tissue-like structures, such as spheroids or organoids, restoring natural cell-ECM interactions and establishing physiochemical gradients (e.g., of oxygen, nutrients, and pH) that are characteristic of real tissues [3] [6].

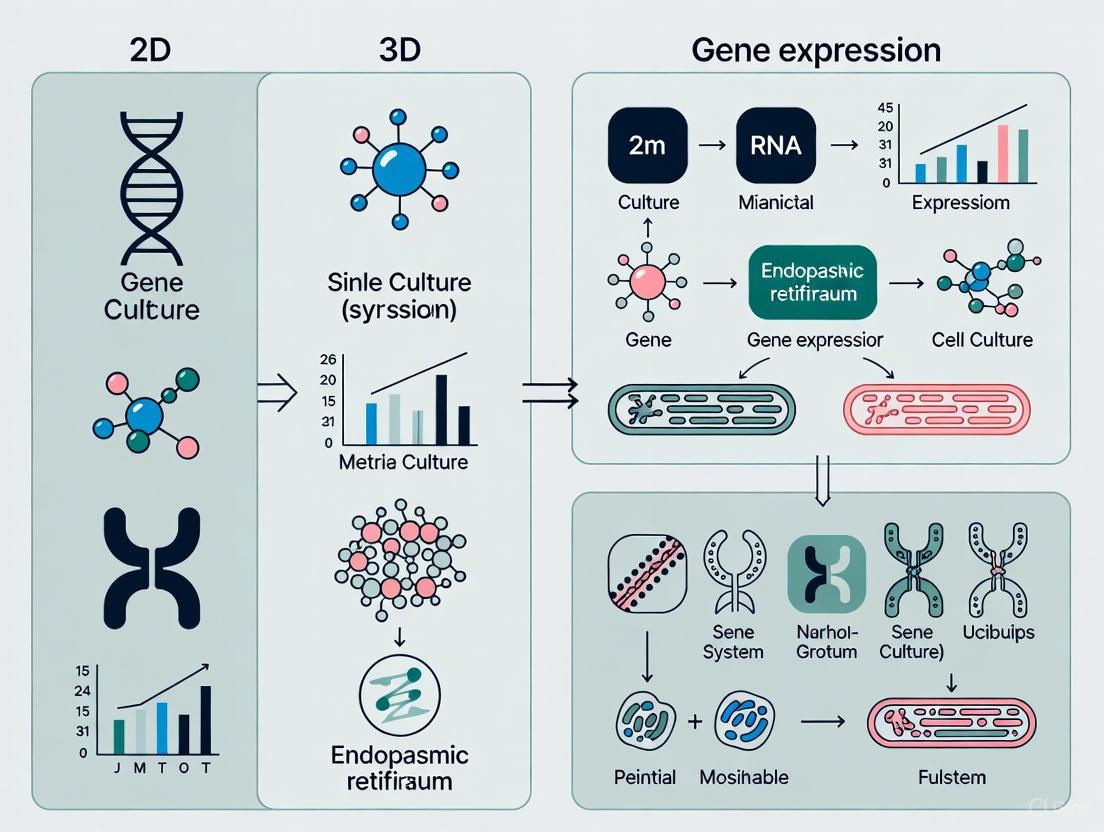

The following diagram illustrates the key architectural and microenvironmental differences that arise from these fundamental design principles.

Architectural and Microenvironmental Differences Between 2D and 3D Cultures

These structural differences have profound functional consequences. The table below summarizes the core characteristics that distinguish these two models.

| Parameter | 2D Cell Culture | 3D Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Flat monolayer on a rigid surface [2] [4] | Three-dimensional, tissue-like structures (e.g., spheroids, organoids) [5] [4] |

| Cell Morphology & Polarity | Altered, spread-out morphology; loss of natural polarity [2] [4] | Preserved native morphology and polarity [2] |

| Cell-Cell & Cell-ECM Interactions | Limited and unnatural interactions [2] [4] | Complex, physiologically relevant interactions [1] [5] |

| Access to Nutrients/Oxygen | Uniform and unlimited access [6] [2] | Creates physiological gradients (e.g., hypoxic cores) [3] [6] |

| Proliferation | Rapid, uniform proliferation [1] | Heterogeneous proliferation with quiescent zones [1] [6] |

| Gene Expression Profile | Altered, does not reflect in vivo conditions well [1] [4] | Closer mimicry of in vivo gene expression [1] [4] |

| Drug Penetration & Response | Direct exposure, often overestimating efficacy [3] [7] | Mimics in vivo drug penetration barriers, more predictive response [1] [7] |

Experimental Data: A Quantitative Comparison

Empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that the choice of culture model significantly impacts experimental outcomes, from basic cell growth to responses to chemotherapeutic agents.

Cell Growth and Viability

A 2023 study on colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines reported that cells grown in 3D cultures displayed a significant (p < 0.01) difference in their pattern of cell proliferation over time compared to 2D cultures [1]. Furthermore, the cell death phase profile was also markedly different [1]. Research using glioblastoma (U251-MG) and lung adenocarcinoma (A549) cell lines has quantified this, showing that while 2D cultures exhibit rapid, exponential growth, proliferation rates in 3D models are significantly reduced. This is likely due to the limited diffusion of nutrients and oxygen within the 3D structure, which more closely mimics the growth constraints of a solid tumor [6].

Drug Response and Resistance

Perhaps one of the most critical comparisons lies in drug sensitivity. In the CRC study, cells in 3D cultures showed a different responsiveness to standard chemotherapeutics like 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and doxorubicin compared to their 2D counterparts [1]. This finding is supported by earlier research on B16 F10 murine melanoma and 4T1 murine breast cancer cells, which demonstrated that cells grown in all tested 3D models showed an increased resistance to dacarbazine and cisplatin compared to the 2D system [7]. This increased resistance in 3D models is a critical finding, as it more accurately reflects the challenging reality of treating solid tumors in patients, where drug penetration and microenvironment-mediated resistance are major hurdles.

Metabolic Differences

Metabolic profiling reveals further key distinctions. A 2025 tumor-on-chip study found that 3D cultures have distinct metabolic profiles, including elevated glutamine consumption under glucose restriction and higher lactate production, indicating an enhanced Warburg effect [6]. The same study highlighted increased per-cell glucose consumption in 3D models, suggesting the presence of fewer but more metabolically active cells than in 2D cultures [6]. This metabolic rewiring is a hallmark of cancer that is poorly captured in 2D systems.

The table below consolidates these key quantitative findings from recent studies.

| Experimental Measure | Key Findings in 2D vs. 3D | Significance / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Proliferation | Significant (p < 0.01) difference in proliferation patterns over time; reduced proliferation rates in 3D [1] [6]. | 3D models better mimic the constrained growth of in vivo tumors, including quiescent cell populations. |

| Response to Chemotherapy | Altered responsiveness in 3D to 5-FU, cisplatin, doxorubicin [1]; Increased resistance to dacarbazine, cisplatin in 3D [7]. | 3D models predict clinical drug resistance more accurately, preventing overestimation of drug efficacy. |

| Metabolic Activity (Lactate Production) | Higher lactate production in 3D cultures, indicating an enhanced Warburg effect [6]. | 3D models more faithfully replicate the altered metabolic phenotype of cancer cells. |

| Glucose Consumption | Increased per-cell glucose consumption in 3D models [6]. | Suggests 3D cultures contain a population of highly metabolically active cells, reflecting tumor heterogeneity. |

| Gene Expression (Transcriptomics) | Significant (p-adj < 0.05) dissimilarity involving thousands of up/down-regulated genes in multiple pathways [1]. | 3D cultures provide a more physiologically relevant gene expression profile for studying molecular mechanisms. |

Methodologies for Comparative Studies

To generate the robust data shown above, specific and reliable experimental protocols are required. Below is a detailed workflow for a standard comparative study, from culture establishment to downstream analysis. The accompanying diagram visualizes this multi-stage process.

General Workflow for Comparative 2D vs. 3D Studies

Establishing 2D and 3D Cultures

- Cell Lines: Studies typically use established cancer cell lines (e.g., HCT-116, Caco-2, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231) or patient-derived cells [1] [5]. These are routinely maintained in standard culture flasks with appropriate media (e.g., DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C [1] [5].

- 2D Culture Protocol: For experiments, cells are harvested using trypsin-EDTA and seeded into standard multi-well plates or Petri dishes at a desired density (e.g., 5 × 10³ cells/well in a 96-well plate) and allowed to adhere as a monolayer [1].

- 3D Spheroid Culture Protocol (Scaffold-Free): A common method involves using U-bottom, ultra-low attachment (ULA) 96-well microplates [1] [5]. After harvesting, an aliquot of cell suspension (e.g., 200 µL containing 5 × 10³ cells) is added into individual wells. The ULA coating and U-bottom geometry prevent cell adhesion and force self-assembly through gravity. Spheroids are maintained in a complete medium (37°C, 5% CO2) with periodic medium changes. Spheroid formation and growth are typically monitored over 72 hours [1] or longer using phase-contrast microscopy.

Key Assays for Comparison

- Proliferation Assay: The CellTiter 96 AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS assay) is widely used [1]. At designated time points, the MTS/PMS mixture is added to the wells and incubated for several hours. Metabolically active cells bio-reduce MTS into a soluble formazan product, which is quantified by measuring absorbance at 490 nm using a plate reader [1].

- Apoptosis Analysis: Apoptotic status is frequently assessed using the FITC Annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) staining kit and flow cytometry [1]. Cells are harvested, stained with FITC-Annexin V and PI, and analyzed. This distinguishes live (Annexin-/PI-), early apoptotic (Annexin+/PI-), late apoptotic (Annexin+/PI+), and dead (PI+) cell populations [1].

- Gene Expression Analysis (RNA sequencing): Total RNA is extracted from both 2D and 3D samples [1]. Following quality control, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is performed. The resulting data undergoes thorough bioinformatic analysis for differential gene expression, pathway analysis (e.g., KEGG, GO enrichment), and other transcriptomic variations [1].

The Impact on Gene Expression: A Core Focus

Transcriptomic analyses provide the most compelling evidence for the superior biological relevance of 3D models. A comprehensive 2023 study on colorectal cancer cell lines employed RNA sequencing and bioinformatic analyses to reveal significant (p-adj < 0.05) dissimilarity in the gene expression profile between 2D and 3D cultures [1]. This dissimilarity involved thousands of up- and down-regulated genes affecting multiple pathways for each cell line tested [1].

Research in breast cancer models reinforces this. Studies on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 spheroids showed notable differences in the expression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers, key receptors (ERs, EGFR, IGF1R), and critical extracellular matrix molecules (syndecans, matrix metalloproteinases) compared to 2D cultures [5]. These molecular changes underpin the observed functional differences in drug response and metabolism. Epigenetically, 3D cultures also more closely resemble in vivo conditions. The CRC study found that 3D cultures and patient-derived Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) samples shared similar methylation patterns and microRNA expression, whereas 2D cells showed an elevated methylation rate and altered microRNA expression [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of 2D versus 3D comparative studies relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their applications.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Application in 2D/3D Studies |

|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates | U-bottom, ULA 96-well plates are essential for scaffold-free spheroid formation. Their coating prevents cell attachment, forcing cells to self-assemble into 3D spheroids [1] [5]. |

| CellTiter 96 AQueous MTS Assay | A colorimetric assay used to quantify cell proliferation and viability in both 2D and 3D formats by measuring the metabolic activity of cells [1]. |

| FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Kit | Used in conjunction with flow cytometry to distinguish and quantify live, early/late apoptotic, and necrotic cell populations following experimental treatments [1]. |

| Matrigel / ECM Hydrogels | A reconstituted basement membrane extract used for scaffold-based 3D cultures. It provides a biologically active matrix that supports complex 3D tissue morphogenesis [5]. |

| Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Scaffolds | Fully synthetic, biodegradable scaffolds (e.g., electrospun membranes) that offer a reproducible and cost-effective alternative for 3D cell growth in drug screening [7]. |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Essential for obtaining high-quality RNA from 2D monolayers and 3D spheroids for subsequent transcriptomic analysis via RNA-seq or qPCR [1]. |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | A standard basal cell culture medium, typically supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), used for routine maintenance and experiments of many cell lines [1] [5]. |

| Trypsin-EDTA Solution | A proteolytic enzyme solution used to detach adherent cells from the culture surface for subculturing and preparing cell suspensions for assays [1] [5]. |

The collective evidence from morphological, functional, and deep molecular profiling unequivocally demonstrates that 3D cell culture models offer a more physiologically relevant platform than traditional 2D monolayers. While 2D cultures remain valuable for high-throughput screening and basic mechanistic studies due to their simplicity and low cost [3], their limitations in predicting in vivo responses are clear. The enhanced complexity of 3D models—recapitulating critical aspects of the tumor microenvironment like gradients, cell-ECM interactions, and spatial organization—leads to more accurate data on gene expression, drug resistance, and cellular metabolism [1] [5] [6].

The future of biomedical research lies not in a binary choice between 2D and 3D, but in strategic, tiered workflows that leverage the strengths of each. A common approach is to use 2D for initial high-volume screening and 3D for predictive validation and deep mechanistic investigation [3]. As 3D technologies continue to advance and integrate with other innovations like microfluidics, bioreactors, and AI-driven analytics, they are poised to dramatically improve the efficiency and success rate of drug development and the fidelity of our basic understanding of cell biology within a tissue context.

The transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture represents more than a technical advancement—it constitutes a fundamental shift in how cells perceive their microenvironment. This dimensional shift profoundly influences cellular identity, function, and metabolic programming. While 2D cultures have served as workhorses for decades due to their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with high-throughput screening [3], they impose artificial physical constraints that disrupt natural cell-ECM interactions, polarity, and spatial organization [2]. The growing recognition that 3D models self-assemble into structures that mimic natural tissues with proper cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions has positioned them as essential tools for understanding the intricate relationships between dimensionality, gene expression, and metabolic function [2].

This guide objectively compares how dimensional context alters fundamental biological processes, with particular emphasis on metabolic pathways and genes governing cell identity. We present supporting experimental data and methodologies to help researchers select appropriate models for specific research applications, especially in drug development and disease modeling where dimensional accuracy significantly impacts translational relevance [3] [8].

Comparative Analysis: 2D vs. 3D Culture Systems

Fundamental Differences in Microenvironment and Cellular Responses

Table 1: Core Characteristics of 2D and 3D Cell Culture Systems

| Feature | 2D Culture | 3D Culture | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Pattern | Monolayer; flat, adherent growth [2] | Multi-layered; expands in all directions [3] | 3D architecture mimics natural tissue organization [2] |

| Cell-ECM Interactions | Limited; disrupted by artificial substrate [2] | Physiologically relevant; dynamic ECM engagement [3] | ECM interactions regulate signaling, differentiation, and survival [2] |

| Spatial Gradients | Uniform nutrient and oxygen access [2] | Natural oxygen, nutrient, and pH gradients form [3] | Gradients create microenvironments similar to in vivo conditions [3] |

| Gene Expression Profiles | Altered; does not mimic in vivo patterns [2] | More accurate; resembles in vivo expression [3] | Better predicts drug responses and disease mechanisms [3] |

| Drug Sensitivity Assessment | Often overestimates efficacy [3] | More predictive of clinical response [3] | Critical for preclinical drug development [3] |

| Cost & Technical Demand | Low cost, simple protocols [3] [2] | More expensive, technically challenging [2] | Infrastructure requirements higher for 3D systems [2] |

Experimental Evidence: Quantitative Impact of Dimensionality

Table 2: Experimentally Observed Differences Between 2D and 3D Cultures

| Parameter | 2D Culture Observations | 3D Culture Observations | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation Rate | Higher proliferation rates [8] | Reduced proliferation; more in vivo-like [8] | Ovarian cancer cell line (PEO4) [8] |

| Drug Response | Increased sensitivity to chemotherapeutics [3] [8] | Enhanced drug resistance; mimics tumor resistance [3] | Cisplatin and paclitaxel testing [8] |

| Gene Expression | 228 differentially expressed genes identified in metabolism [9] | More accurate gene expression fidelity [3] | Preterm birth placenta analysis [9] |

| Metabolic Pathway Activation | Altered arachidonic acid and glutathione metabolism [9] | Physiological pathway regulation [9] | Bioinformatics analysis of placental tissue [9] |

| Tumor Modeling | Homogeneous cancer cell growth [2] | Heterogeneous layers with hypoxic cores [3] | Multicellular tumor spheroids [3] |

Dimensionality-Induced Alterations in Metabolic Pathways

Key Metabolic Genes Regulated by Dimensional Context

Research comparing dimensional influences on gene expression has identified specific metabolic genes that show differential regulation between 2D and 3D environments. In a study investigating spontaneous preterm birth, which integrated bioinformatics analysis and machine learning algorithms, three key metabolism-related hub genes were identified: ANPEP, CKMT1B, and PLA2G4A [9] [10]. These genes demonstrated significant alterations in expression patterns when analyzed in a dimensional context relevant to tissue physiology.

The functional enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes in dimensional comparisons have repeatedly highlighted disruptions in arachidonic acid metabolism and glutathione metabolism pathways [9]. These pathways play crucial roles in cellular signaling, inflammation, and oxidative stress response—processes known to be dimension-sensitive. The identification of these specific pathway alterations underscores how dimensional context can influence fundamental metabolic processes relevant to both development and disease pathogenesis.

Cancer Metabolism and Dimensionality

Comprehensive analyses of metabolic gene alterations across 32 human cancers have revealed that genes involved in lipid metabolism are the most frequently altered, followed by those involved in carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism [11]. This pattern of metabolic reprogramming is more accurately captured in 3D culture systems, which preserve the tissue architecture and microenvironmental gradients essential for proper metabolic function.

Notably, cancers with higher frequencies of metabolic gene alterations (HM supertype) demonstrate significantly worse clinical outcomes compared to those with lower alteration frequencies (LM supertype), with median overall survival of 68.9 months versus 116.2 months, respectively [11]. This clinical correlation highlights the critical importance of using physiologically relevant models that accurately capture metabolic heterogeneity when studying cancer biology and therapeutic responses.

Experimental Protocols for Dimensional Comparison Studies

3D Culture Techniques and Methodologies

Suspension Cultures on Non-Adherent Plates

Protocol: Single cells are seeded on non-adherent plates with medium; 3D structures typically form within 3 days of culture [2]. Applications: Simple, rapid formation of spheroids; suitable for high-throughput screening approaches. Technical Considerations: Some strongly adherent cell lines may require specialized plates coated with polystyrene or covalently bound hydrogel to prevent attachment [2].

Cultures in Gel-Like Substances

Protocol: Cells are embedded in Matrigel or agarose-based hydrogels. For agarose: dissolved low-melting agarose with cell medium is poured on a plate and incubated until solidified to create a base layer, followed by a top layer containing cells [2]. Applications: Ideal for studying tissue-like structure formation, invasion, and metastasis. Technical Considerations: Matrigel contains endogenous bioactive ingredients that may influence structure formation; recovery of cells for analysis can be challenging [2].

Scaffold-Based Cultures

Protocol: Cells migrate among and attach to biodegradable scaffolds made of materials such as silk, collagen, laminin, or alginate, filling the inter-fiber spaces [2]. Applications: Excellent for tissue engineering applications; compatible with standard molecular biology kits for DNA/RNA and protein isolation. Technical Considerations: Scaffold topography and material composition can significantly influence cell behavior and experimental outcomes [2].

Protocol for Comparative Proliferation Analysis in 2D vs. 3D Systems

Cell Line: PEO4 (high-grade serous ovarian cancer) [8] 2D Proliferation Assessment:

- Seed 10,000 cells/well in 96-well plates

- After 24 hours, administer treatment (e.g., cisplatin: 50-0.4 μM; paclitaxel: 50-0.4 nM)

- Incubate for 72 hours

- Add MTT solution (2 mg/ml) and incubate for 3 hours

- Solubilize formazan crystals in DMSO

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm [8]

3D Proliferation Assessment:

- Print 3,000 PEO4 cells/well as "Imaging model" using PEG-based hydrogels with RGD functionalization

- Allow 7 days for spheroid establishment

- Administer treatments identical to 2D system

- After 72 hours, measure viability using CellTiter-Glo 3D assay [8]

Data Normalization: Normalize all data to untreated controls; correct for background signal from matrix devoid of cells [8].

Visualization of Dimensionality Effects on Cellular Processes

Experimental Workflow for 2D-3D Comparative Studies

Experimental Workflow for Dimensional Comparison

Metabolic Pathways Sensitive to Dimensional Context

Metabolic Pathways Altered by Dimensionality

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for 2D and 3D Cell Culture Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Dimensional Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, collagen I, agarose [2] | Provides 3D scaffolding for cell growth and organization | Essential for 3D culture; not used in 2D |

| Specialized Plates | Ultra-low attachment plates [3] | Prevents cell adhesion; promotes spheroid formation | Critical for scaffold-free 3D cultures |

| Bio-printing Systems | Rastrum 3D bioprinter [8] | Enables precise 3D structure fabrication | Advanced 3D model creation |

| Hydrogel Systems | PEG-based hydrogels with RGD [8] | Synthetic 3D microenvironment with controlled properties | Tunable 3D culture platforms |

| Viability Assays | CellTiter-Glo 3D [8], MTT [8] | Quantifies cell viability and proliferation | Assay optimization required for 3D penetration |

| Molecular Analysis Kits | RNA/DNA isolation kits compatible with 3D [2] | Nucleic acid extraction from complex 3D structures | Must accommodate ECM components |

The evidence presented demonstrates that dimensional context exerts profound influences on gene expression, metabolic pathway regulation, and ultimately cellular identity. The comparative data reveals that 3D culture systems provide superior pathophysiological relevance for studying metabolic processes, drug responses, and disease mechanisms, while 2D systems retain value for high-throughput screening and basic mechanistic studies [3].

The emergence of standardized protocols and specialized reagents for 3D culture has addressed earlier technical barriers, making these systems increasingly accessible for routine research [2]. The research community is moving toward integrated model systems that strategically employ both 2D and 3D approaches at different stages of the research pipeline [3]. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of each system while acknowledging their limitations, ultimately accelerating the translation of basic research findings to clinical applications.

For researchers investigating metabolic pathways and cell identity, the selection of an appropriate dimensional context should be guided by the specific research question, with 3D models providing essential physiological relevance for studies requiring accurate tissue modeling, drug penetration assessment, and metabolic pathway analysis [3] [8].

The transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research. This guide objectively compares the transcriptomic landscapes of cells cultured in these systems, synthesizing current experimental data to demonstrate that 3D cultures consistently restore gene expression profiles that more closely mimic in vivo conditions. We present quantitative evidence from multiple cancer types and stem cells, highlighting significant differences in pathway activation, drug response, and morphological characteristics. The compiled data underscore the superior physiological relevance of 3D models, providing researchers with a critical resource for selecting appropriate culture systems based on empirical molecular evidence.

For decades, two-dimensional (2D) cell culture has been a cornerstone of biological research, yet it presents significant limitations in mimicking the in vivo microenvironment. Cells cultured in 2D monolayers lack three-dimensional architecture, resulting in altered cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions that fundamentally change their biological behavior [2]. These limitations manifest molecularly as distorted gene expression patterns, aberrant splicing events, and altered topology that diverge substantially from native tissue states [2]. Consequently, data generated from 2D models often poorly predict human physiological responses, contributing to high failure rates in drug development where approximately 90% of discovered drugs that reach clinical trials fail to obtain FDA approval [1].

Three-dimensional (3D) culture systems have emerged as a transformative approach that bridges the gap between conventional 2D cultures and in vivo models. By restoring spatial organization, gradient dynamics, and mechanical cues, 3D cultures re-establish tissue-relevant transcriptional programs that more accurately reflect human biology [12]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of 2D versus 3D culture systems through detailed experimental data and transcriptomic evidence, offering researchers a scientific foundation for model system selection.

Results: Comparative Transcriptomic and Functional Analyses

Multi-Cancer Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Widespread Differences

Multiple studies across different cancer types have consistently demonstrated substantial transcriptomic differences between 2D and 3D culture systems through RNA sequencing analyses.

Table 1: Transcriptomic Differences Between 2D and 3D Cultures Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Upregulated Pathways in 3D | Key Downregulated Pathways in 3D | Significant DEGs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | Tumorgenicity-related genes, ECM organization | Cell cycle progression | Thousands of genes (up/down-regulated) | [1] |

| Cervical Cancer (SiHa cells) | Immune activation, inflammation, angiogenesis, tissue remodeling | Tissue development, cell differentiation | 79 significant DEGs independent of HPV effects | [13] [14] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Glycolysis, nutrient metabolism | Ribosome biogenesis, cell cycle progression | Distinct metabolic and transcriptional profiles | [15] |

In colorectal cancer research, a comprehensive comparative study found "significant (p-adj < 0.05) dissimilarity in gene expression profile between 2D and 3D cultures involving thousands of genes (up/down-regulated) of multiple pathways for each cell line" [1]. The study further demonstrated that compared to 2D cultures, cells in 3D formats displayed significant differences in the pattern of cell proliferation over time, cell death phase profile, and responsiveness to chemotherapeutic agents including 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and doxorubicin [1].

In cervical cancer models, transcriptomic analysis of SiHa cells revealed upregulation of genes associated with immune activation, inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling in 3D cultures compared to their 2D counterparts [13]. Notably, HPV16 viral gene expression (E1, E2, E6, and E7) was significantly higher in 3D cultures, more closely mimicking the in vivo viral activity observed in actual tumors [14].

Drug Response and Resistance Profiles

The physiological differences between 2D and 3D cultures significantly impact drug response profiles, with 3D systems demonstrating enhanced predictive value for clinical outcomes.

Table 2: Comparative Drug Response in 2D vs. 3D Culture Systems

| Parameter | 2D Culture | 3D Culture | Physiological Relevance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug sensitivity | Enhanced sensitivity to chemotherapeutics | Increased resistance mimicking in vivo tumors | 3D models more accurately predict clinical drug resistance | [1] [12] |

| Diffusion gradients | Uniform drug distribution | Heterogeneous distribution creating nutrient and oxygen gradients | Recapitulates avascular tumor nodules | [13] [12] |

| Proliferation status | Predominantly uniform proliferation | Mixed proliferating and quiescent cell populations | Mimics tumor heterogeneity | [1] [16] |

| Metabolic activity | Homogeneous metabolic profile | Distinct metabolic adaptations including increased glycolysis | Better reflects tumor metabolism | [15] |

3D cultures accommodate "surface-lying and deeply buried cells, proliferating and non-proliferating regions, oxygen-deprived hypoxic cells, and a well-oxygenated outer layer of cells" [1]. This architectural complexity creates diffusion barriers that lead to spatial heterogeneity in nutrient and oxygen levels, regions of quiescence and hypoxia, and metabolic heterogeneity - all of which better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment (TME) of solid tumors compared to conventional 2D monolayer cultures [13]. These attributes confer enhanced resistance to many anti-cancer drugs compared to 2D monolayer cultures, thus allowing for more clinically predictive studies of drug response [13].

Epigenetic and Chromosomal Architecture Differences

Beyond transcriptomic changes, 3D cultures also better replicate in vivo epigenetic patterns and higher-order genomic structures. In colorectal cancer models, researchers found that "epigenetically, 3D cultures and FFPE [Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded patient samples] shared the same methylation pattern and microRNA expression, while 2D cells showed elevation in methylation rate and altered microRNA expression" [1].

A study investigating the effects of spatial constraints on chromosome conformation in mouse hepatocytes revealed "significant differences in higher-order genomic interactions, notably in compartment identity and strength as well as in topologically associating domain (TAD)–TAD interactions" between 2D and 3D cultures [17]. These structural genomic differences were associated with up-regulated expression of genes involved in physiological hepatocyte functions in the 3D-cultured cells, suggesting that differences in genomic structure are critically important for transcriptional regulation [17].

Diagram 1: Fundamental architectural differences between 2D and 3D culture systems that drive transcriptomic variations.

Methods: Experimental Protocols for 2D/3D Comparative Studies

Establishing 3D Culture Models

The methodology for creating 3D cultures varies depending on the specific model system, but several well-established approaches are commonly used in comparative transcriptomic studies:

Spheroid Formation Using U-bottom Plates: For cervical cancer transcriptomic studies, researchers seeded "5,000 cells in each well of a 96-well Nunclon Sphera, U-bottom plate (ThermoFisher), then centrifuged at 70 × g for 5 min before placing in the incubator" [13]. Media replacement was performed every 2-3 days, with spheroid formation monitored for 7-9 days before analysis [13]. This method creates scaffold-free 3D structures through forced aggregation.

Hydrogel-Based 3D Cultures: For modeling tumor invasion, researchers culture "breast cancer cell-derived and patient-derived organoids in a 3D Matrigel/Hydrogel overlay system with calibrated elastic moduli ranging from 150-320Pa present in normal human breast tissues to 1100-5700Pa observed in some stiff breast tumors" [18]. This approach allows researchers to study how extracellular matrix stiffness controls tumor invasion.

Scaffold-Based Systems: Novel platforms like Bio-Blocks—a hydrogel-based culture system—are designed to "replicate in vivo-like environments while addressing the challenges of traditional culture systems" [19]. These systems feature unique micro-/macro-architecture that circumvents diffusional constraints and reduces cellular stress.

Transcriptomic Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Standard workflow for comparative transcriptomic analysis of 2D and 3D culture systems.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: In comparative studies, total RNA is typically extracted using commercial kits such as the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (ThermoFisher) with on-column DNase treatment [13]. RNA purity and concentration are assessed using spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop ND-1000), and quality verification is performed using methods such as the MycoStrip detection kit for mycoplasma contamination [13].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: For transcriptomic analysis, libraries are prepared from high-quality RNA and sequenced using platforms such as the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with 150 bp paired-end reads [13]. This generates comprehensive data for subsequent bioinformatic analysis.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline: A standard analytical workflow includes:

- Quality Control: Raw sequencing reads are evaluated using FastQC for adapter content, read length distribution, and per-base sequence quality scores [13].

- Alignment: Reads are aligned to appropriate reference genomes using aligners such as STAR v2.7.10b [13].

- Quantification: Transcript/gene-level expression abundance is quantified from aligned reads using tools like RSEM v1.3.3 [13].

- Differential Expression: Statistical analysis identifies differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with appropriate multiple testing corrections.

- Pathway Analysis: Enrichment analysis reveals biological pathways and processes differentially active between culture conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 2D/3D Comparative Transcriptomic Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Example Products | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment Plates | Facilitate spheroid formation by preventing cell adhesion | Nunclon Sphera U-bottom 96-well plates | Enables scaffold-free 3D spheroid formation [1] [13] |

| Extracellular Matrix Substitutes | Provide biomimetic scaffold for 3D growth | Corning Matrigel matrix, hydrogels | Tunable mechanical properties to mimic different tissue types [18] [19] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | High-quality RNA isolation from 3D structures | PureLink RNA Mini Kit | Includes DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination [13] |

| Cell Viability Assays | Assess metabolic activity in 3D structures | CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS) | Adapted for 3D culture formats [1] |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits | Quantify cell death mechanisms | FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit | Requires extraction of cells from 3D matrices [1] |

| Next-Generation Sequencers | Transcriptome profiling | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | 150 bp paired-end reads recommended for comprehensive coverage [13] |

The comprehensive transcriptomic evidence presented in this guide demonstrates unequivocally that 3D cell culture systems restore in vivo-like expression profiles across multiple cell types and disease models. The data reveal substantial differences in pathway activation, chromosomal architecture, drug response, and cellular heterogeneity that favor 3D models as more physiologically relevant platforms for biomedical research. While 2D cultures remain valuable for specific applications, their documented transcriptomic limitations necessitate a strategic transition to 3D systems for studies requiring physiological predictive value. As the field advances, standardizing 3D culture protocols and analytical pipelines will be essential for maximizing the translational potential of these biologically superior models.

The Role of the Extracellular Matrix in Mechanotransduction and Genomic Regulation

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is far more than a passive structural scaffold for tissues; it is a dynamic, signaling-active entity that continuously provides cells with mechanical and biochemical cues. Through mechanotransduction—the process by which cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals—the ECM directly influences genomic regulation and cell fate decisions [20] [21]. This interplay is fundamental to physiological processes from embryonic development to tissue homeostasis, and its dysregulation is implicated in diseases ranging from fibrosis to cancer [22] [21]. The study of these mechanisms, however, is profoundly affected by the choice of experimental model. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture on rigid plastic surfaces presents an oversimplified mechanical environment that fails to recapitulate the complex three-dimensional (3D) context in which cells reside in vivo [20] [23]. This guide objectively compares 2D and 3D culture models, focusing on their performance in elucidating the role of the ECM in mechanotransduction and genomic regulation, to inform the experimental design of researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D Microenvironments

The microenvironment created by the culture system directly dictates the nature of cell-ECM interactions. The table below summarizes the core differences between these two models.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of 2D vs. 3D Cell Culture Models

| Feature | 2D Cell Culture | 3D Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Pattern | Single layer on a flat, rigid surface [3] | Multi-layered, expanding in all directions to form spheroids or organoids [3] |

| Cell-ECM Interaction | Primarily basal; unnatural, forced adhesion [23] | Natural, omnidirectional engagement with the ECM [20] [23] |

| Spatial Architecture | Lacks tissue-like organization [3] | Exhibits tissue-like structure with surface-lying and buried cells [1] |

| Mechanical Cues | Uniform stiffness (often very high); limited mechanical confinement [20] | Complex mechanics including stiffness, viscoelasticity, and confinement [20] |

| Microenvironment | Homogeneous distribution of oxygen, nutrients, and pH [3] | Creates natural gradients of oxygen (hypoxic cores), nutrients, and waste products [1] [3] |

The mechanical properties of the ECM—including its stiffness, viscoelasticity, and topography—are critical regulators of cell behavior. In a 3D context, the ECM exhibits complex mechanical properties such as non-linear elasticity (strain-stiffening) and stress relaxation, which are often absent or simplified in 2D models [20]. Furthermore, cells in 3D environments are mechanically confined by the surrounding matrix, which restricts changes in cell volume and shape, forcing cells to employ different strategies for migration and force generation compared to 2D [20]. This fundamental difference in mechanical engagement underlies the stark contrasts observed in cellular phenotypes and signaling outputs between the two models.

Impact on Cellular Phenotype and Experimental Outcomes

The choice of culture model has a profound impact on observable cellular behaviors, from basic morphology to responses relevant to drug discovery. The following table compares key phenotypic outcomes.

Table 2: Phenotypic and Functional Outcomes in 2D vs. 3D Cultures

| Outcome Measure | 2D Cell Culture Findings | 3D Cell Culture Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Morphology | Artificial, flattened, and stretched morphology [7] [23] | In vivo-like morphology; formation of spheroids and organoids [7] [1] |

| Proliferation Rate | Typically high and uniform proliferation [1] | Heterogeneous proliferation; slower growth rates, mimicking in vivo tumors [1] |

| Gene Expression Profile | Does not closely match in vivo tumor profiles; altered epigenetic patterns [1] | Greater fidelity to in vivo tumors; more physiological expression and methylation patterns [1] |

| Drug Resistance | Often overestimates drug efficacy [7] [3] | Increased resistance to chemotherapeutics (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, doxorubicin) [7] [24] [1] |

| Apoptosis Profile | Higher baseline of apoptotic cells [1] | Lower levels of apoptosis, resembling in vivo tumors [1] |

These divergent outcomes highlight a critical limitation of 2D models: their poor predictive power for in vivo responses. For instance, cells in 3D cultures show increased resistance to chemotherapeutic agents like cisplatin and doxorubicin, a phenomenon attributed to factors like limited drug penetration, the presence of quiescent cells, and altered survival signaling [7] [24] [1]. This makes 3D models, such as multicellular tumor spheroids, indispensable for realistic pre-clinical drug screening.

Molecular Mechanisms of Mechanotransduction: A 3D Perspective

In 3D microenvironments, mechanotransduction occurs through distinct pathways that converge to regulate genomic output. The following diagram synthesizes the key mechanisms by which ECM-derived mechanical cues in a 3D setting influence nuclear activity and gene expression.

Diagram 1: 3D Mechanotransduction to Gene Expression

Key Molecular Players and Pathways

- Integrin-Mediated Sensing: In 3D, integrins such as α2β1 and α3β1 bind to ECM components like collagen I and fibrin, initiating the formation of focal adhesions [20]. The maturation of these adhesions is sensitive to 3D matrix stiffness and degradability, triggering intracellular signaling cascades involving kinases like Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) [20] [25].

- YAP/TAZ Translocation: The Hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ are central mechanotransducers. In stiff 2D environments or upon increased actomyosin contractility in 3D, they translocate to the nucleus and act as transcriptional co-regulators, driving the expression of proliferative and pro-fibrotic genes [25] [21]. Their regulation is a key point of divergence between 2D and 3D models.

- Ion Channel Activation: Mechanosensitive ion channels, such as Piezo1, are critical for sensing 3D confinement and hydrostatic pressure [20] [21]. Their activation leads to calcium influx, which in turn can modulate various signaling pathways, including those that regulate the actin-binding protein cofilin and the transcriptional regulator MRTF-A, impacting serum response factor (SRF)-mediated transcription [25].

- Nuclear Mechanotransduction: Forces are transmitted to the nucleus via the LINC complex, which connects the cytoskeleton to the nuclear lamina [25]. This can result in nuclear deformation, changes in chromatin architecture, and direct mechanical regulation of transcription, for instance through the action of nuclear actin and myosin [25].

Experimental Support: Comparative Data from Key Studies

Robust experimental evidence underscores the superior physiological relevance of 3D models. The following table quantifies performance differences between 2D and 3D cultures in published experiments.

Table 3: Experimental Data from Comparative 2D vs. 3D Studies

| Experimental Metric | Cell Line / Model | 2D Culture Results | 3D Culture Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Resistance (Cisplatin) | B16 F10 murine melanoma & 4T1 murine breast cancer | Higher sensitivity | Increased resistance observed across all 3D models | [7] [24] |

| Drug Resistance (5-Fluorouracil) | Colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines (Caco-2, HCT-116, etc.) | Higher sensitivity | Increased resistance in 3D spheroid models | [1] |

| Gene Expression Fidelity | Colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines vs. patient FFPE samples | Altered methylation & miRNA profiles; poor match to in vivo | Methylation & miRNA patterns more closely matched patient FFPE samples | [1] |

| Transcriptomic Profile | Colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines (RNA-seq) | Significant dissimilarity to in vivo | Thousands of genes differentially expressed; profiles more physiological | [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Generating 3D Spheroids for Mechanotransduction Studies

The following is a standardized protocol for establishing 3D spheroid cultures, as utilized in the cited studies [7] [1]:

- Cell Seeding: Prepare a single-cell suspension. Seed an aliquot of 200 μL of cell suspension (at a density of 5 × 10³ cells) into individual wells of a Nunclon Sphera super-low attachment U-bottom 96-well microplate. This plate prevents cell adhesion to the plastic, forcing cells to aggregate and form spheroids.

- Spheroid Culture: Maintain the spheroids in a complete cell culture medium (e.g., DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS) under a standard humidified atmosphere of 5% CO₂ at 37°C.

- Medium Maintenance: Perform three consecutive 75% medium changes every 24 hours to ensure adequate nutrient supply and waste removal without disrupting the forming spheroids.

- Harvesting and Analysis: Spheroids are typically ready for experimentation after 72 hours of culture. They can be harvested for various downstream analyses, including:

- RNA Extraction for transcriptomic studies (e.g., RNA sequencing).

- Cell Viability and Apoptosis Assays using kits like FITC Annexin V.

- Immunofluorescence to visualize protein localization (e.g., YAP/TAZ nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio).

- Drug Treatment by adding chemotherapeutic agents directly to the culture medium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Selecting the appropriate tools is critical for successfully modeling ECM-mediated mechanotransduction. The table below lists key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 2D/3D Mechanotransduction Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nunclon Sphera U-bottom Plates | Scaffold-free 3D culture; promotes spheroid formation via ultra-low attachment surface | Generating uniform multicellular tumor spheroids (MCTS) for drug testing [1] |

| Reconstituted Basement Membrane (rBM) | Scaffold-based 3D culture; provides a biologically active, nanoporous ECM environment | Culturing epithelial cells to maintain polarized, organotypic structures [20] |

| Reconstituted Collagen-I Gels | Tunable 3D scaffold; allows control over stiffness and density to study matrix mechanics | Investigating fibroblast migration and cancer cell invasion in a defined 3D matrix [20] |

| CellTiter 96 AQueous Assay (MTS) | Colorimetric measurement of cell proliferation and metabolic activity | Quantifying cell growth and drug response in both 2D and 3D formats [1] |

| FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Kit | Flow cytometry-based detection of apoptotic and dead cell populations | Comparing apoptosis profiles between 2D monolayers and 3D spheroids [1] |

| Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Scaffolds | Synthetic, reproducible scaffolds for 3D cell culture (e.g., electrospun membranes) | Providing a cost-effective and defined alternative to natural ECM scaffolds [7] |

The evidence demonstrates that 3D cell culture models provide a functionally superior system for studying the role of the ECM in mechanotransduction and genomic regulation. By more accurately replicating the mechanical constraints, architectural complexity, and biochemical gradients of native tissues, 3D models yield data on gene expression, drug resistance, and cellular phenotype that are more predictive of in vivo outcomes. While 2D cultures remain useful for high-throughput initial screening due to their simplicity and low cost, the future of mechanistic research and predictive drug development lies in the adoption of advanced 3D models. The field is moving towards integrated, multi-model workflows that combine the speed of 2D with the physiological depth of 3D systems and patient-derived organoids, all enhanced by AI-driven analysis of complex mechanobiological data [3]. For researchers aiming to translate in vitro findings into clinical success, embracing these sophisticated 3D microenvironments is no longer an option but a necessity.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing 3D Models for Gene Expression Studies

The transition from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, particularly in studies investigating gene expression. Traditional 2D culture systems, where cells grow in a single layer on flat plastic surfaces, have been the standard for decades due to their simplicity, low cost, and protocol standardization [3]. However, these systems fail to accurately recapitulate the complex architecture and cellular interactions found in living tissues, leading to altered cell morphology, proliferation, and gene expression profiles that poorly translate to in vivo conditions [3] [16]. This limitation is especially critical in cancer research, where the tumor microenvironment significantly influences disease progression and treatment response.

Scaffold-based 3D culture techniques provide a solution by creating an artificial extracellular matrix (ECM) that allows cells to grow in all directions, mimicking their natural environment more closely [16]. These advanced systems facilitate proper cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions, generate natural gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and pH, and ultimately yield more physiologically relevant gene expression data [3] [26]. Among the various scaffold options available, hydrogels, Matrigel, and synthetic polymers have emerged as leading platforms, each offering distinct advantages and limitations for specific research applications. The growing importance of these technologies is reflected in the scientific literature, with publications on 3D cell cultures showing a marked increase over recent years [16].

This guide objectively compares the performance of these scaffold-based techniques within the context of gene expression studies, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to inform their model selection for more predictive and translationally relevant outcomes.

Technical Comparison of Scaffold-Based Techniques

Composition and Properties

Hydrogels: Three-dimensional (3D) polymer networks formed by chemical or physical crosslinking of polymers rich in hydrophilic groups, capable of absorbing large quantities of water while maintaining structural integrity [27] [28]. They can be derived from natural sources (e.g., collagen, chitosan, alginate, hyaluronic acid) or synthetic polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol (PEG), polylactic acid (PLA), poly(vinyl acetate) (PVA)), or created as hybrid systems combining both approaches [27] [16]. Their key characteristics include high water content, tunable mechanical properties, and excellent biocompatibility, closely mimicking the native ECM [28].

Matrigel: A commercially available basement membrane matrix extracted from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma tumor, composed of laminin, collagen IV, entactin, and various growth factors [16]. This complex, biologically active composition provides an environment that supports cell differentiation and tissue-specific organization, making it particularly valuable for organoid culture and angiogenesis studies.

Synthetic Polymers: Artificially engineered materials (including PEG, PLA, poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA), and PNIPAAm) that offer precise control over physical and chemical properties such as stiffness, degradation rate, and porosity [27] [16]. These scaffolds are characterized by their high reproducibility, mechanical strength, and customizable functionality, though they may lack inherent bioactivity without additional modification [27].

Comparative Performance in Gene Expression Studies

Table 1: Comparative analysis of scaffold-based 3D culture techniques

| Feature | Hydrogels | Matrigel | Synthetic Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | High [28] | High [16] | Variable (can be optimized) [27] |

| Biodegradability | Tunable [27] | High (enzyme-dependent) [16] | Controllable [27] |

| Mechanical Properties | Adjustable (soft to stiff) [27] | Limited adjustability (soft) [16] | Highly tunable [27] [16] |

| Bioactive Signals | Present in natural variants [27] | Rich and complex [16] | Limited (requires functionalization) [27] |

| Reproducibility | Moderate to high [27] | Low (batch variability) [28] | High [27] |

| Cost | Moderate [27] | High [16] | Low to moderate [27] |

| Key Advantages | Mimic native ECM; Tunable properties [27] [28] | Biologically active; Supports complex morphogenesis [16] | Highly reproducible; Customizable architecture [27] [16] |

| Key Limitations | Potential batch variability (natural); Complexity in synthesis [27] | Tumor-derived; Variable composition; Limited stiffness control [16] | May lack bioactivity; Potential cytotoxicity concerns [27] |

Table 2: Impact on gene expression profiles in 3D vs 2D culture systems

| Gene Category | 2D Culture Expression | 3D Culture Expression | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stemness Markers (CD133, Nestin, Oct4, Sox2, Nanog) | Lower [26] | Upregulated [26] | Enhanced stem-like properties |

| Cell Cycle Regulators (CCNA, CCNB, CCND, CCNE) | Variable [26] | Upregulated [26] | Altered proliferation patterns |

| Apoptosis-related (p21, p27) | Higher [26] | Downregulated [26] | Enhanced survival signaling |

| EMT Markers | Lower [26] | Upregulated [26] | Increased invasive potential |

| Cytokine Secretion (IL-6) | Lower [29] | Significantly higher [29] | Enhanced pro-tumorigenic signaling |

Experimental evidence demonstrates that 3D scaffold environments significantly alter gene expression patterns compared to traditional 2D cultures. A comprehensive study investigating glioma cells (U87, U251, and HS683) cultured in 3D collagen scaffolds revealed upregulation of genes associated with stemness (CD133, Nestin, Oct4, Sox2, Nanog), cell cycle progression (CCNA, CCNB, CCND, CCNE), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), migration, and invasion compared to 2D cultured cells [26]. These expression changes corresponded with enhanced functional malignancy, suggesting that 3D environments better recapitulate the aggressive phenotype of in vivo tumors.

Similarly, research using patient-derived scaffolds (PDS) from breast tumor tissue demonstrated that breast cancer cells (MCF-7) cultured on tumor PDS showed significant overexpression of invasiveness hub genes (CAV1, CXCR4, CNN3, MYB, and TGFB1) and secreted higher levels of IL-6 (122.91 vs. 30.23 pg/10⁶ cells) compared to those cultured on normal PDS [29]. These findings underscore how tumor-specific ECM components drive more aggressive gene expression profiles, highlighting the critical importance of scaffold composition in disease modeling.

Experimental Protocols for Gene Expression Analysis

3D Culture in Collagen Scaffolds

Scaffold Preparation:

- Prepare collagen scaffolds using commercially available collagen solutions (e.g., rat tail collagen type I) according to manufacturer specifications [26].

- Adjust collagen concentration to achieve desired mechanical stiffness (typically 2-5 mg/mL).

- For pore size control, subdivide scaffolds into different categories (e.g., Scaffold A: 30-50 µm; Scaffold B: 70-100 µm) [26].

- Sterilize scaffolds using ethylene oxide gas or UV irradiation.

- Equilibrate scaffolds in cell culture medium for 24 hours at 37°C before cell seeding [26].

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Prepare single-cell suspensions at appropriate density (e.g., 1×10⁵ cells in 20 µL medium per scaffold) [26].

- Slowly pipette cell suspension onto pre-hydrated scaffolds.

- Maintain scaffolds at 37°C for 4 hours to allow cell attachment.

- Transfer each scaffold to a well of a 12-well cell culture plate containing 2 mL complete medium.

- Replace culture medium every 2 days [26].

Cell Harvesting for Gene Expression Analysis:

- Wash scaffolds with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) three times.

- Submerge in 0.25% trypsin at 37°C for 10 minutes, gently pipetting 2-3 times during digestion to dissociate cells [26].

- Terminate digestion with complete medium containing serum.

- Repeat digestion process once to maximize cell yield.

- Collect combined digested fluid and centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Proceed with RNA extraction from cell pellet using standard methods (e.g., TRIzol reagent) [26].

Patient-Derived Scaffold (PDS) Technique

Tissue Decellularization:

- Obtain patient tumor and normal tissue samples through surgical resection with appropriate ethical approvals [29].

- Process tissues using an SDS-based decellularization protocol to remove cellular components while preserving ECM structure and composition.

- Validate complete decellularization through H&E staining (absence of cell nuclei), DNA quantification (<50 ng/mg tissue), and ECM composition analysis (collagen, glycosaminoglycans) [29].

Scaffold Characterization:

- Assess ECM preservation through histological staining (trichrome, PAS, Sirius red, alcian blue) [29].

- Quantify key ECM components: collagen content via hydroxyproline assay, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) via dimethylmethylene blue assay [29].

- Evaluate mechanical properties through tensile testing to determine Young's modulus [29].

- Analyze microstructure and porosity using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [29].

3D Cell Culture on PDS:

- Seed MCF-7 breast cancer cells (or other relevant cell lines) onto characterized PDS.

- Culture for 7-15 days, assessing cell viability and proliferation at designated time points using MTT assay [29].

- Quantify cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-6) in culture media using ELISA [29].

- Harvest cells for gene expression analysis of invasiveness markers (CAV1, CXCR4, CNN3, MYB, TGFB1) using RT-qPCR [29].

Signaling Pathways in 3D Microenvironments

The altered gene expression observed in 3D scaffold cultures is regulated through multiple signaling pathways that respond to biomechanical and biochemical cues from the extracellular microenvironment. Research indicates that apoptotic pathways, along with the Wnt, Sonic Hedgehog, and Notch signaling pathways, may be involved in mediating these transcriptional changes [26]. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways implicated in the response of cancer cells to 3D microenvironments:

Signaling Pathways in 3D Microenvironments

These pathway activations result from the unique biomechanical properties, architectural constraints, and biochemical signaling present in 3D scaffold environments compared to traditional 2D cultures. The increased stiffness of tumor-derived ECM has been shown to activate mechanosensitive signaling pathways that promote invasive gene expression [29]. Additionally, the spatial organization in 3D cultures creates nutrient and oxygen gradients that mimic the in vivo tumor microenvironment, further influencing transcriptional programs through hypoxia-inducible factors and metabolic stress pathways [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents for scaffold-based 3D culture experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Hydrogels | Collagen (Type I), Fibrinogen, Hyaluronic acid, Chitosan, Alginate, Gelatin [16] | Mimic native ECM composition; Support cell adhesion and proliferation |

| Synthetic Polymers | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Polylactic acid (PLA), Poly(vinyl acetate) (PVA), PNIPAAm [27] [16] | Provide tunable mechanical properties; High reproducibility |

| Basement Membrane Matrix | Matrigel, Geltrex [16] | Organoid culture; Angiogenesis studies; Differentiation assays |

| Decellularized Scaffolds | Patient-derived scaffolds (PDS) [29] | Patient-specific ECM modeling; Tumor microenvironment studies |

| Crosslinking Agents | Genipin, Glutaraldehyde, EDAC, NHS [27] | Modify hydrogel mechanical properties; Control degradation rate |

| Characterization Kits | MTT assay, DNA quantification, Hydroxyproline assay, GAG assay [26] [29] | Assess cell viability; Validate decellularization; Quantify ECM components |

| Gene Expression Analysis | TRIzol reagent, RT-qPCR kits, Primers for stemness/EMT/invasion markers [26] [29] | Quantify transcriptional changes; Validate functional phenotypes |

This toolkit represents essential materials required for implementing scaffold-based 3D culture techniques and analyzing resulting gene expression changes. Selection of specific reagents should be guided by research objectives, with natural hydrogels preferred for physiological relevance, synthetic polymers for controlled reductionist studies, and patient-derived scaffolds for translational cancer research [27] [16] [29].

Scaffold-based 3D culture techniques represent a significant advancement over traditional 2D systems for gene expression research, particularly in cancer biology and drug development. The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that hydrogels, Matrigel, and synthetic polymers each provide unique microenvironments that profoundly influence cellular transcription patterns, yielding data more reflective of in vivo conditions. While each scaffold type has distinct advantages and limitations, their collective value lies in enabling researchers to ask more physiologically relevant questions about cellular behavior, drug responses, and disease mechanisms.

The future of scaffold-based research points toward increasingly sophisticated systems, including patient-derived scaffolds that capture individual-specific microenvironments [29], hybrid hydrogels combining the benefits of natural and synthetic materials [27], and advanced fabrication techniques such as 4D bioprinting that introduce dynamic, time-responsive elements into scaffold design [28]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will further bridge the gap between in vitro models and in vivo physiology, accelerating the development of more effective therapeutics and personalized medicine approaches.

Cell culture systems are indispensable tools in basic and clinical in vitro research. For decades, the classically preferred model has been the static dish culture system, which generates adherent two-dimensional (2D) cell monolayers [30]. However, these 2D systems do not reflect the in vivo reality, where cells grow within a complex three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment within a vascular network [30]. This limitation has significant consequences for research outcomes, particularly in gene expression studies and drug development.

The transition to 3D cell culture represents a paradigm shift toward more physiologically relevant models. Among 3D approaches, scaffold-free methods have emerged as powerful techniques that allow cells to self-assemble into structures that closely mimic natural tissues. Unlike scaffold-based systems that use external matrices, scaffold-free techniques rely on the innate ability of cells to organize themselves, promoting direct cell-cell interactions and forming complex architectures that recapitulate key aspects of in vivo conditions [31] [32]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the primary scaffold-free methods—spheroids, organoids, and hanging drop cultures—within the context of their impact on gene expression and cellular behavior compared to traditional 2D systems.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Distinguishing Scaffold-Free 3D Models

Scaffold-free 3D culture systems are defined by their reliance on cellular self-organization without synthetic or natural supporting matrices. The nomenclature in this field is sometimes misunderstood, and clear distinctions exist between the main model types [31]:

- Spheroids: Simple, spherical clusters of cells that form through self-aggregation in a scaffold-free environment. They typically contain one or multiple cell types and model basic cellular processes but lack the organizational complexity of specific organs [31].

- Organoids: More complex structures with the ability to self-differentiate and exhibit organ-specific characteristics and functions. They demonstrate higher-level organization that more closely mimics human organs, making them ideal for investigating disease mechanisms and developing personalized medicine approaches [31].

- Hanging Drop Cultures: A specific technical approach for generating spheroids and organoids by suspending cells in inverted droplets of medium, using gravity and surface tension to promote aggregation without external scaffolds [32].

The Formation Process of Scaffold-Free Structures

The formation of scaffold-free structures follows a defined sequence of phases [31]:

- Aggregation: Dispersed cells initially form loose aggregates through transmembrane receptors (integrins) that facilitate cell-cell adhesion.

- Compaction: The aggregates become more densely packed, assuming a spherical shape through continued cellular reorganization.

- Growth: The compacted structures continue to develop, potentially forming internal organization, nutrient gradients, and complex cytoarchitecture that more closely mimics the in vivo microenvironment.

This self-organization process fundamentally alters the cellular microenvironment compared to 2D culture, leading to the development of chemical gradients and distinct structural zones within the 3D structures [31].

Methodological Comparison of Scaffold-Free Techniques

Technical Approaches and Protocols

Scaffold-free methods encompass several established techniques, each with specific protocols and applications:

Hanging Drop Method

- Protocol: Cells are suspended in small droplets (typically 10-30 µL) of culture medium on the underside of a culture dish lid. The lid is then inverted over a reservoir containing PBS or medium to maintain humidity. Gravity causes cells to settle at the liquid-air interface, promoting aggregation into spheroids within 24-72 hours [32] [33].

- Experimental Considerations: The hanging drop method is straightforward and requires no specialized equipment beyond standard tissue culture materials. However, droplet volume limits spheroid size, and the method can be labor-intensive for large-scale studies due to the need for manual handling of individual droplets [31].

Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates

- Protocol: Specialized plates with covalently bonded hydrogel coatings that prevent cell attachment. Cells are seeded into these plates, where the inability to adhere to the surface forces them to aggregate and form spheroids [34] [33].

- Experimental Considerations: ULA plates are compatible with high-throughput screening and automated liquid handling systems. They provide excellent reproducibility and minimize handling compared to hanging drop methods but involve higher consumable costs [34].

Magnetic Levitation and Nanoparticle Assembly

- Protocol: Cells are incubated with magnetic nanoparticles and then exposed to magnetic fields using specialized devices that draw cells together to form spheroids [35]. This method enables consistent incorporation of multiple cell types from the initial formation stages.

- Experimental Considerations: This approach provides excellent control over spheroid composition and size, with the magnetic field facilitating consistent structure formation. The need for nanoparticle labeling introduces an additional step and potential variable [35].

Comparative Analysis of Scaffold-Free Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Scaffold-Free 3D Culture Techniques

| Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Cases | Throughput Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Drop | Low cost; simple setup; no specialized equipment required; suitable for hypoxia gradient studies [31] [36] | Difficult handling and media exchange; limited droplet volume restricts spheroid size; labor-intensive for large-scale studies [34] [31] | Initial drug screening; fundamental research on cell-cell interactions; studies requiring precise control over initial cell numbers [36] | Low to medium [31] |

| ULA Plates | High reproducibility; compatible with high-throughput screening; minimal handling required; suitable for long-term culture [34] [37] | Higher consumable costs; limited ability to control initial spheroid size beyond seeding density; potential batch-to-batch variability in plates [34] | High-throughput drug screening; long-term toxicity studies; production of uniform spheroid populations [34] [37] | High [34] |

| Magnetic Levitation | Precise control over spheroid composition and size; enables consistent incorporation of multiple cell types; rapid assembly [35] | Requires nanoparticle labeling; specialized equipment needed; additional variable of nanoparticle effects to consider [35] | Complex co-culture models; immune-tumor interaction studies; applications requiring precise spatial control [35] | Medium to high [35] |

Gene Expression Differences: 2D vs. 3D Scaffold-Free Cultures

Transcriptomic Reprogramming in 3D Environments

The transition from 2D to 3D scaffold-free culture systems induces significant changes in gene expression patterns that underlie functional differences observed in 3D models. Research comparing human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSCs) cultured in 3D scaffolds versus 2D films revealed that substrate structure alone had stronger effects on gene expression than substrate polymer composition [38]. Pathway analysis demonstrated that 3D cultures and osteogenic supplements regulated similar ontological pathways, with particularly strong enrichment for TGF-β and cell-adhesion/ECM-receptor pathways in 3D environments [38].

A recent study on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) cultured using the hanging drop method revealed extensive transcriptome reprogramming [32]. RNA-Seq analysis showed that 3D MSCs upregulated receptors and cytokine production while downregulating proteolysis-, cytoskeletal-, extracellular matrix-, and adhesion-related genes compared to their 2D counterparts [32]. This transcriptional reshaping enhanced the cells' response capabilities to incoming signals, fundamentally altering their functional profile.

Cancer-Relevant Gene Expression Alterations

In cancer research, 3D spheroid models demonstrate gene expression profiles that more closely match those of real tumors compared to 2D cultures [34]. Studies using HeLa cell spheroids have shown increased drug resistance associated with cytoskeletal reorganization and overexpression of specific genes (SLC2A1, ALDOC, and PFKFB4) [36]. These expression changes in 3D models reflect adaptations to the tumor microenvironment that cannot be replicated in 2D systems, including hypoxia response, metabolic reprogramming, and altered cell-cell communication pathways.

Side-by-side CRISPR knockout screens performed on tumor cells cultured as 3D spheroids versus 2D monolayers revealed that 3D spheroids identified more cancer-relevant hits from driver pathways known to be essential for tumor growth, including p53, TGF-β, and hypoxia signaling [35]. This demonstrates how gene essentiality itself differs between 2D and 3D contexts, with 3D models providing more clinically relevant insights.

Quantitative Gene Expression Data

Table 2: Gene Expression Differences Between 2D and 3D Scaffold-Free Cultures

| Gene Category/Pathway | Expression Change in 3D | Functional Implications | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Markers (Oct4, Sox2, Nanog) | Upregulated [32] | Enhanced stemness and regenerative capacity [32] | Mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) [32] |

| Cytoskeletal & ECM Genes | Downregulated [32] | Reduced cell stiffness; modified cell-matrix interactions [32] | Mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) [32] |

| Drug Resistance Genes (SLC2A1, ALDOC, PFKFB4) | Upregulated [36] | Increased chemoresistance; altered metabolic activity [36] | HeLa cell spheroids [36] |

| TGF-β Signaling Pathway | Enriched [38] | Enhanced differentiation potential; tissue development [38] | Human bone marrow stromal cells [38] |

| Cell-Adhesion/ECM-Receptor Pathways | Strongly enriched [38] | Modified cell-cell communication; tissue organization [38] | Human bone marrow stromal cells [38] |

| Chemokine Receptors (CXCR4) | Upregulated [32] | Enhanced homing capability; improved recruitment to target tissues [32] | Mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) [32] |

Experimental Workflows and Key Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Establishing Scaffold-Free Cultures

The following diagram illustrates the general experimental workflow for establishing and analyzing scaffold-free 3D cultures, integrating common steps across different methods:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for scaffold-free 3D culture establishment and analysis

Signaling Pathways Activated in 3D Microenvironments

The transition to 3D culture activates specific signaling pathways that drive the functional differences observed between 2D and 3D systems:

Diagram 2: Signaling pathways activated in 3D microenvironments

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Scaffold-Free 3D Culture

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment Plates | Prevents cell adhesion, forcing aggregation into spheroids [34] | High-throughput drug screening; long-term spheroid culture [34] [37] | Coating consistency affects reproducibility; well geometry influences spheroid formation [34] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Labels cells for magnetic assembly of spheroids [35] | Complex co-culture models; consistent incorporation of multiple cell types [35] | Nanoparticle concentration optimization required; potential effects on cell physiology [35] |

| CellTiter-Glo 3D Assay | Measures ATP content as viability indicator in 3D structures [37] [35] | Drug efficacy studies; metabolic activity monitoring in spheroids [37] | Optimized for penetration into 3D structures; more accurate than standard viability assays [37] |

| Extracellular Matrix Proteins (Collagen I, Matrigel) | Optional supplementation to enhance spheroid compaction [34] | Modeling invasive phenotypes; enhancing structural integrity in loose aggregates [34] [33] | Concentration-dependent effects on morphology; Matrigel has batch-to-batch variability [34] |

| Live-Cell Imaging Systems (Incucyte) | Monitors spheroid growth and morphology in real-time [34] | Kinetic studies of spheroid development; migration and invasion assays [34] | Requires specialized equipment; enables longitudinal analysis without sample destruction [34] |

Applications in Drug Development and Disease Modeling

Enhanced Predictive Power in Drug Screening