Building Robust Data Preprocessing Pipelines for Single-Cell Foundation Model Training

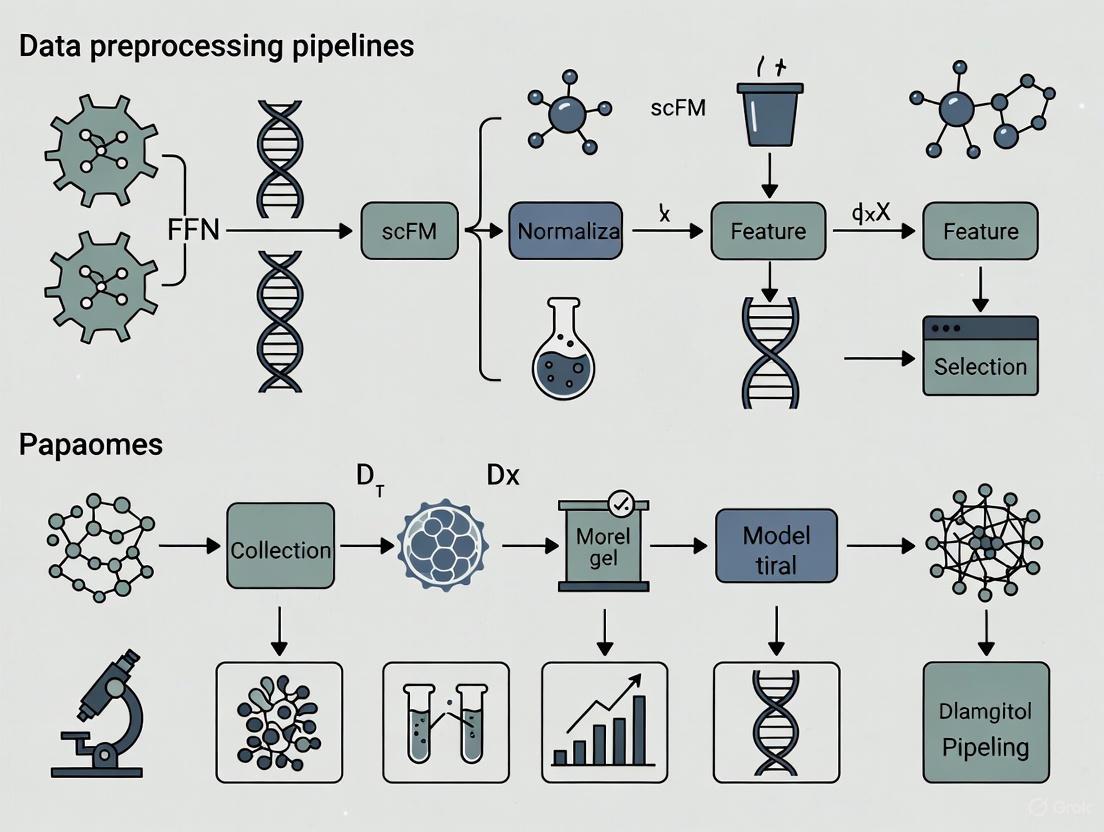

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on constructing effective data preprocessing pipelines for single-cell Foundation Model (scFM) training.

Building Robust Data Preprocessing Pipelines for Single-Cell Foundation Model Training

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on constructing effective data preprocessing pipelines for single-cell Foundation Model (scFM) training. It covers foundational concepts, practical methodologies, critical optimization strategies, and robust validation techniques. The content addresses key challenges such as data heterogeneity, tokenization strategies, and bias mitigation, emphasizing how high-quality, well-structured preprocessing is crucial for developing generalizable and powerful models that can advance drug discovery and biomedical research.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Data Challenges in scFM Preprocessing

Understanding the Single-Cell Foundation Model (scFM) Ecosystem and its Data Demands

Single-cell Foundation Models (scFMs) are large-scale artificial intelligence models, pre-trained on vast datasets of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, designed to learn universal biological representations that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks [1]. These models, inspired by the success of large language models, treat individual cells as "sentences" and genes or genomic features as "words" or "tokens" [1]. Their development is driven by the rapid expansion of public single-cell data repositories, which now encompass tens of millions of cells profiling diverse cell types, states, and conditions [1]. This technical support article guides researchers through the data preprocessing pipelines and experimental protocols essential for effective scFM training and application.

The scFM landscape features several prominent models with distinct architectures and pretraining strategies. The table below summarizes key models and their primary data characteristics.

Table 1: Key Single-Cell Foundation Models and Their Data Profiles

| Model Name | Core Architecture | Pretraining Data Scale | Key Specialization / Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT [2] [3] | Generative Pretrained Transformer (Decoder) | Over 33 million cells [3] | Multi-omic integration, perturbation prediction |

| Geneformer [4] [5] | Transformer | Not Specified in Results | Gene-network biology, leveraging rank-based input |

| scBERT [1] [2] | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) | 1.12 million human cells [3] | Cell type annotation |

| scFoundation [4] [2] | Transformer | Not Specified in Results | Gene-level tasks, uses value projection |

| GeneMamba [5] | State Space Model (BiMamba) | Scalable to over 50 million cells [5] | Computational efficiency, long-sequence modeling |

Data Prerequisites for Pretraining

A critical ingredient for any scFM is the compilation of large and diverse datasets. Successful pretraining requires:

- Data Volume and Diversity: Models are trained on massive, aggregated corpora from public archives like CZ CELLxGENE, the Human Cell Atlas, and NCBI GEO, which provide a broad coverage of cell types and states necessary for learning generalizable patterns [1].

- Data Quality Challenges: A significant challenge is managing inconsistent data quality, batch effects, technical noise, and varying processing steps across different studies and experiments [1]. Effective pretraining requires careful dataset selection, filtering of cells and genes, and quality control [1].

Section 2: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Preprocessing and Tokenization

Q: What is the best method to tokenize single-cell data for foundation models? My model performance is sub-optimal.

Single-cell data is not naturally sequential, unlike text, so tokenization strategies are critical. Incompatible tokenization can lead to poor model convergence and an inability to capture biological relationships.

A: The choice of tokenization strategy is a fundamental architectural decision. Below is a comparison of the primary methods.

Table 2: Comparison of scRNA-seq Data Tokenization Strategies

| Tokenization Strategy | How It Works | Advantages | Disadvantages | Used By |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank-based [5] | Genes are ranked by expression level within each cell; the sequence of gene IDs is the input. | Robust to batch effects and noise; captures relative expression. | Loses information on absolute expression magnitude. | Geneformer, GeneMamba |

| Bin-based [5] | Expression values are grouped into predefined, discrete bins (e.g., low, medium, high). | Preserves some information about expression level distribution. | Can introduce information loss; sensitive to binning parameters. | scBERT, scGPT |

| Value Projection [5] | Continuous expression values are projected into an embedding space via a linear layer. | Maintains full, continuous data resolution. | Diverges from standard NLP tokenization; impact not fully known. | scFoundation |

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Audit Your Data: If your data has significant technical variation, consider a rank-based approach for its inherent robustness [5].

- Define Your Goal: If predicting subtle shifts in expression is critical, a value projection method may be more appropriate [5].

- Consult the Literature: Use the tokenization method employed by the model you are building upon or fine-tuning (see Table 2).

This logical workflow for selecting and implementing a tokenization strategy can be visualized as follows:

Model Selection and Performance

Q: How do I choose the right scFM for my specific biological task, such as cell type annotation or perturbation prediction?

A: Model performance is highly task-dependent. A comprehensive 2025 benchmark study revealed that no single scFM consistently outperforms all others across diverse applications [4]. Use the following guidance:

Table 3: Model Selection Guide Based on Task and Resources

| Primary Task | Recommended Model Considerations | Computational Constraint Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Annotation | scBERT is specialized for this, but newer models like scGPT also show strong performance [1] [2]. | For limited resources, a simpler baseline model (e.g., on HVGs) may be more efficient for a single, specific dataset [4]. |

| Perturbation Prediction | scGPT has been successfully adapted for predicting outcomes to both genetic and novel chemical perturbations [3]. | Models like GeneMamba offer a more computationally efficient alternative to transformers for large-scale perturbation studies [5]. |

| Multi-batch Integration | scGPT, Geneformer, and GeneMamba have demonstrated strong capabilities in integrating datasets and removing batch effects [4] [5]. | |

| Gene-level Tasks | Geneformer and scFoundation have shown strong capabilities in tasks focused on gene relationships and function [4] [2]. |

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Clearly define your primary downstream task (e.g., annotation, integration, prediction).

- Assess your computational resources and dataset size. For smaller, focused studies, simpler non-foundation models may be sufficient and more efficient [4].

- Consult the "Scientist's Toolkit" below for key resources that can aid in model evaluation and selection, such as the BioLLM framework [2].

Computational Efficiency and Fine-tuning

Q: Training or fine-tuning an scFM is too computationally expensive. What are my options?

A: The quadratic complexity of the transformer architecture can indeed be a bottleneck. Consider these approaches:

- Alternative Architectures: Explore next-generation models designed for efficiency. For example, GeneMamba uses a State Space Model (SSM) architecture with linear computational complexity, significantly reducing training time and memory requirements while maintaining performance [5].

- Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT): Instead of updating all model parameters, use adapter-based methods. For instance, you can inject a small, trainable drug-conditional adapter layer to fine-tune a model for molecular perturbation prediction, training less than 1% of the original model's parameters [3]. This preserves the pre-trained knowledge and prevents overfitting on small datasets.

Section 3: The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details key resources and materials for researchers working with scFMs.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scFM Workflows

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BioLLM Framework [2] | A unified system with standardized APIs that simplifies the process of using, comparing, and benchmarking different scFMs. | Enables streamlined model switching and consistent evaluation. |

| Public Data Atlases [1] | Provide the large-scale, diverse, and annotated single-cell datasets required for pre-training and benchmarking scFMs. | CZ CELLxGENE, Human Cell Atlas, PanglaoDB. |

| Cell Ontology-Informed Metrics [4] | Novel evaluation metrics that assess whether a model's learned representations are consistent with established biological knowledge. | scGraph-OntoRWR, Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD). |

| Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) [3] | A set of techniques that allows adaptation of large models to new tasks by training only a small number of parameters, saving compute resources. | Includes adapter layers (e.g., scDCA) and prefix tuning. |

The relationships between these core components in a typical scFM research workflow are illustrated below:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary differences between CZ CELLxGENE Discover and the Human Cell Atlas (HCA) Data Portal? The core difference lies in their structure and access methods. CZ CELLxGENE Discover is a highly integrated and standardized corpus of data, accessible via a powerful graphical user interface and a programmable API (Census) for efficient data slicing [6] [7]. In contrast, the Human Cell Atlas (HCA) Data Portal is a vast, community-generated repository where you can access raw and processed data from numerous independent projects within the global HCA consortium [8] [9]. CZ CELLxGENE is often used for direct analysis of a curated collection, while the HCA provides a broader view of ongoing single-cell research efforts.

Q2: I need to download a specific subset of data for analysis in R or Python. Which resource is most suitable? For this purpose, the CZ CELLxGENE Census is specifically designed for programmatic data access [7]. It allows you to query and download precise slices of data based on cell or gene metadata. The data can be directly loaded into popular objects like AnnData (for Scanpy in Python), Seurat objects (for R), or SingleCellExperiment objects (for Bioconductor in R), which significantly streamlines your workflow [10] [7].

Q3: How can I ensure the scRNA-seq data I use from these repositories is reproducible and well-annotated? Repositories increasingly adhere to community standards like the Minimum Information about a Single-Cell Experiment (minSCe) guidelines [11]. When depositing or selecting data, check for complete metadata, including detailed protocols for cell isolation, library construction, and sequencing. The HCA Data Coordination Platform and CZ CELLxGENE work to standardize this information. For cell type annotations, which are often inferred computationally, ensure the analysis methods are reproducible and clearly documented [11].

Q4: My analysis requires a comprehensive, tissue-specific reference atlas. Where should I look? Both resources offer this. The HCA is actively building consensus tissue-specific atlases, such as the Human Lung Cell Atlas (HLCA), which integrates data from 486 individuals [12]. CZ CELLxGENE Discover also allows you to browse data by tissue and offers a "Cell Guide" that acts as an encyclopedia for cell types, providing definitions, marker genes, and relevant datasets [6]. For a multi-tissue, baseline reference from healthy donors, the Tabula Sapiens collection, available on CZ CELLxGENE, is an excellent resource [6] [12].

Q5: I am studying cancer. Are there specialized databases I should use alongside these general repositories? Yes, cancer-specific databases are highly valuable. Resources like TISCH and CancerSEA are tailored for cancer single-cell research [12]. TISCH provides detailed annotations of the tumor microenvironment across many cancer types, while CancerSEA focuses on decoding various functional states of cancer cells (e.g., invasion, stemness) [12]. You can use CZ CELLxGENE or the HCA to find original cancer datasets and then leverage these specialized portals for deeper, cancer-focused analysis.

Comparison of Major Single-Cell Data Repositories

The table below summarizes the key quantitative and qualitative features of major data sources to help you select the right one for your research needs.

| Repository | Scale (Cells) | Data Type | Primary Access Method | Key Features & Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZ CELLxGENE Discover [6] | 33M+ cells, 436 datasets [6] | Standardized, integrated scRNA-seq | Web UI, Census API (Python/R) | Differential Expression, Explorer, Cell Guide, Census for programmatic access [6] [7] |

| Human Cell Atlas (HCA) Data Portal [8] | 70.3M cells, 523 projects [8] | Community-generated, multi-omic | Web Portal, Data Browser | Raw & processed data from global consortium; organized by biological network [8] [9] |

| Single Cell Portal (Broad Institute) [12] | 654 datasets [12] | Individual study datasets | Web UI, Direct download | Interactive visualizations (t-SNE, UMAP), often includes study-specific analysis tools [10] [12] |

| Tabula Sapiens [12] | Data from 15 individuals, 24 tissues [12] | Integrated multi-tissue atlas | Web UI, CZ CELLxGENE | A reference of "healthy" or baseline cell states across the human body [12] |

| GEO / SRA [10] | 3,000+ scRNA-seq studies [11] | Raw sequencing data (FASTQ) & processed data | Web search, Direct download | Broad repository; often the original data source for other portals; requires significant preprocessing [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Data Utilization

Protocol 1: Accessing and Querying Data via CZ CELLxGENE Census API

This protocol is essential for researchers who need to programmatically extract specific data slices for large-scale analysis, such as training scFM models.

- Installation: Install the

cellxgene_censuspackage in your Python or R environment. - Connect to Census: Open a connection to the Census data. The package will handle the cloud-based data access.

- Query Data: Use the SOMA interface to specify query criteria based on cell metadata (e.g., tissue, cell type, disease) and/or gene metadata.

- Data Retrieval: Load the queried data directly into an AnnData (Python/Scanpy), Seurat (R), or SingleCellExperiment (R/Bioconductor) object [7].

- Local Analysis: Proceed with your standard preprocessing and analysis workflow on the in-memory object.

Key Consideration: The Census data may include both full-length and 3'/5' sequencing data. Use the metadata variable is_primary_data to filter out duplicate cells present across multiple datasets if needed [7].

Protocol 2: Building a Custom Consolidated Dataset from the HCA Data Portal

This protocol guides you through aggregating data from multiple projects on the HCA portal for a meta-analysis.

- Define Scope: Identify the biological question (e.g., T-cell states in lung cancer) to determine relevant tissues, diseases, and cell types.

- Browse and Filter: Use the HCA Data Portal's exploration tools to filter projects by organism, organ, or assay type [8].

- Select Projects: Manually curate a list of projects based on experimental design and metadata completeness, referring to minSCe guidelines [11].

- Data Download: Download the raw count matrices and associated metadata for each selected project.

- Harmonize and Integrate: This is the most critical and challenging step. Use batch correction tools like Harmony, BBKNN, or Seurat's CCA to integrate the datasets, ensuring that cell types are aligned across different studies [13] [12].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Data Handling

The table below lists essential computational "reagents" for working with public single-cell data repositories.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| CZ CELLxGENE Census [7] | Programmatic data access | Efficiently query and load specific data subsets from CZ CELLxGENE into Python/R. |

| Seurat [10] [13] | scRNA-seq analysis (R) | An all-in-one toolkit for QC, normalization, clustering, and integration of datasets. |

| Scanpy [13] | scRNA-seq analysis (Python) | A comprehensive Python-based toolkit for analyzing single-cell gene expression data. |

| SingleCellExperiment [10] | Data object (R/Bioconductor) | A standard S4 class for storing single-cell data; interoperable with many Bioconductor packages. |

| AnnData [7] | Data object (Python) | The standard Python object for single-cell data, used by Scanpy and CellxGene Census. |

| Harmony [12] | Data integration | Algorithm for integrating datasets to remove batch effects while preserving biological variation. |

Workflow Diagrams

Data Access Workflow for scFM Research

Single-Cell Data Ecosystem Overview

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core purpose of a preprocessing pipeline for single-cell foundation model (scFM) training?

The preprocessing pipeline transforms raw, unstructured single-cell data into a standardized, numerical format that a deep learning model can process. Its primary goal is to remove unwanted technical variation (e.g., from differences in sequencing depth) while preserving meaningful biological signals (e.g., cell type differences). This involves critical steps like normalization, which makes gene counts comparable between cells, and tokenization, which converts the normalized gene expression profiles into a sequence of discrete tokens that serve as the model's input [14] [1]. A robust pipeline is essential for building a model that generalizes well across diverse datasets and biological conditions.

FAQ 2: My dataset has an abundance of zeros. Is this a technical error I need to fix?

Not necessarily. A high abundance of zeros is an inherent feature of single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets, stemming from both biological factors (a gene being truly inactive in a cell) and technical factors (mRNA molecules not being captured or amplified during library preparation, often called "dropout") [14]. Your preprocessing strategy should account for this. While some imputation methods exist to address technical zeros, many successful scFMs are trained directly on the sparse, normalized count data without complex imputation, allowing the model to learn from the data's inherent structure [1].

FAQ 3: Why is tokenization necessary since I already have a gene expression matrix?

While a gene expression matrix is structured, it lacks the sequential nature that transformer-based models, the backbone of most foundation models, are designed to process. Tokenization standardizes this data into discrete input units, or "tokens," analogous to words in a sentence for a language model [1]. For scFMs, a "token" typically represents a gene (or a feature) along with its expression value. Since genes have no natural order, a crucial part of tokenization is defining a sequence, often by ranking genes by their expression level within each cell before feeding them to the model [1].

FAQ 4: How do I choose a normalization method for my scRNA-seq data?

There is no single best-performing normalization method, and the choice can impact downstream analysis like clustering [15]. The selection depends on your data's characteristics and your analysis goals. The table below summarizes some commonly used methods. It is considered good practice to test multiple methods and compare their results in cell clustering and embedding [14] [15].

Table 1: Common scRNA-seq Data Normalization Methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Scaling (e.g., LogNorm) | Divides counts by total per cell and log-transforms [15]. | Simple, fast, widely used. | May not effectively normalize high-abundance genes [15]. |

| SCTransform | Uses regularized negative binomial regression [15]. | Models technical noise, avoids overfitting, generates depth-independent residuals. | More computationally intensive than global scaling. |

| Scran | Pools cells to compute size factors [15]. | Robust for data with many zero counts. | Performance can depend on the pooling strategy. |

| BASiCS | Uses a Bayesian hierarchical model [15]. | Can integrate spike-in RNAs to quantify technical variation. | Requires spike-in genes or technical replicates. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance Due to Data Quality and Batch Effects

Problem: Your scFM fails to generalize or shows inconsistent performance across different datasets, likely due to unaddressed technical artifacts and batch effects.

Investigation & Resolution:

Audit Your Data Sources: The first step is to scrutinize the data used for pretraining. scFMs are trained on large, aggregated datasets from public repositories like CZ CELLxGENE, GEO, and SRA [1]. Check for consistency in:

- Cell Isolation Protocol: Was the data generated using microfluidics, droplets, or microplates? [14]

- Library Preparation: Was it a full-length or 3'/5' counting-based method? [14]

- Sequencing Depth: Are there vast differences in the number of reads per cell across studies?

- Solution: Implement rigorous quality control and filtering for cells and genes during the data compilation stage. The goal is to create a high-quality, non-redundant training corpus [1].

Evaluate Normalization Efficacy: Test if your normalization method has successfully removed the technical variation.

- Metric: Use the silhouette width to assess the clarity of cell clustering after normalization. Employ the K-nearest neighbor batch-effect test to check if cells from the same cell type but different batches mix well [14].

- Solution: If batches are not integrating well, try a method like SCTransform, which explicitly models the relationship between gene expression and sequencing depth, or explore batch-effect correction tools after normalization [14] [15].

Issue 2: Inefficient Tokenization and Input Representation

Problem: The model struggles with long sequences (memory issues) or fails to capture fine-grained, nucleotide-level information, often due to a suboptimal tokenization strategy.

Investigation & Resolution:

Diagnose the Tokenization Bottleneck: Standard tokenization that treats each gene as a token can lead to very long sequences, hitting the context window limits of transformer models [16].

- Solution - Adaptive Tokenization: For long sequences, consider a method like Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), which merges frequent character sequences into tokens, effectively shortening the sequence length. For tasks requiring fine-grained resolution (e.g., predicting single-nucleotide variants), nucleotide-level (NUC) tokenization is preferable, though more resource-intensive. Frameworks like BiRNA-BERT demonstrate that a dual-tokenization approach, dynamically selecting between BPE and NUC based on input length, can be highly effective [16].

Define a Robust Gene Ordering: Since genes lack a natural sequence, the model requires an arbitrary but deterministic order.

- Solution: A common and effective strategy is to rank genes by their expression values within each cell before creating the token sequence [1]. This creates a consistent input structure for the model to learn from. You can also enrich tokens with metadata, such as prepending a special token representing the cell's identity or adding modality indicators for multi-omics data [1].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from raw single-cell data to model-ready tokens, integrating the key troubleshooting points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Tools and Platforms for scFM Preprocessing

| Item / Tool | Function in the Preprocessing Pipeline |

|---|---|

| 10X Genomics Chromium | A widely used droplet-based platform for generating single-cell gene expression data. It incorporates cell barcodes and UMIs for accurate molecule counting [14]. |

| Spike-in RNAs (e.g., ERCC) | Exogenous RNA controls added to the sample before library prep. They create a standard curve to help distinguish technical noise from biological variation and are used by some normalization methods (e.g., BASiCS) [14] [15]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Random nucleotide sequences added during reverse transcription. UMIs allow bioinformatics tools to count individual mRNA molecules and correct for PCR amplification biases [14]. |

| CZ CELLxGENE | A platform providing unified access to millions of curated and annotated single-cell datasets, which is crucial for assembling the large, diverse pretraining corpora needed for scFMs [1]. |

| Seurat / Scanpy | Popular software toolkits for single-cell analysis. They provide built-in functions for common normalization methods (e.g., NormalizeData in Seurat) and subsequent steps like clustering and visualization [15]. |

| SentencePiece | A language-agnostic tokenization tool that can be applied to DNA or protein sequences, as it processes raw data without pre-defined boundaries, making it suitable for biological data [17]. |

For researchers in drug discovery and development, the generalizability of a machine learning model—its ability to perform accurately on new, unseen data—is a critical determinant of its real-world utility. A model that excels on its training data but fails in a different clinical context or with a new patient population offers little value. The foundation of model generalizability is not the algorithm itself, but the quality of the data it learns from. This technical support center outlines how a robust data preprocessing pipeline is the direct, non-negotiable link between raw, imperfect data and a generalizable model, particularly within the high-stakes context of single-chain Fragment variable (scFv) research and foundation model training.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is data preprocessing considered so critical for model generalizability in scientific research? Data preprocessing is crucial because real-world data is messy, inconsistent, and often incomplete. Statistical models and machine learning algorithms are mathematical constructs that assume clean, well-structured input. Feeding them raw data leads to the "garbage in, garbage out" phenomenon, where the model learns spurious patterns or noise instead of the true underlying biological signal. Preprocessing directly addresses this by resolving data quality issues, thereby enabling the model to learn robust, generalizable patterns rather than artifacts of a specific, messy dataset [18]. In regulated environments, the FDA's 2025 draft guidance emphasizes data quality and representativeness as foundational for establishing model credibility for a specific Context of Use (COU) [19].

2. What are the most common data quality issues that preprocessing must address? The most frequent challenges researchers encounter are detailed in the table below.

Table: Common Data Quality Issues and Their Impacts

| Data Issue | Description | Potential Impact on Model |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Values | Absent data points in a collection, common in experimental data. | Can lead to biased estimates, reduced statistical power, and errors if not handled properly [20] [18]. |

| Outliers | Data points that deviate significantly from other observations. | Can skew model training, leading to inaccurate representations of data trends [20]. |

| Data Imbalance | Unequal representation of different conditions or classes in the dataset. | Can cause fairness problems, where a model has high accuracy for majority conditions but poor performance for minority conditions [21]. |

| Inconsistent Scales | Features or variables measured on different numerical scales (e.g., age vs. salary). | Can cause algorithms that rely on distance calculations to be dominated by the feature with the largest scale [18]. |

| Non-Numerical Data | Categorical or text data that most algorithms cannot process directly. | Prevents model training, as algorithms typically require numerical input [18]. |

3. How does the "Context of Use" (COU) influence preprocessing decisions? The FDA's 2025 guidance stresses that AI/ML models must be built and validated for a precise Context of Use (COU)—the specific regulatory question the model informs [19]. The COU dictates every preprocessing choice. For instance:

- If the COU involves predicting drug efficacy across global populations, your preprocessing must include rigorous checks for dataset representativeness and bias mitigation across demographics [19].

- If the COU is for a diagnostic model, handling missing values from certain lab equipment or normalizing data from different sources becomes a critical preprocessing step to ensure consistent performance [20]. The COU defines what "high quality" means for your specific model.

4. What is the difference between data preprocessing and data augmentation? Data preprocessing is applied to the entire dataset (training, validation, and test sets) to make the data usable and improve quality. Its goal is to clean and prepare the base data. In contrast, data augmentation is a technique applied only to the training set to artificially increase its size and diversity by creating slightly modified copies of existing data [22]. This is common in image data (e.g., rotations, contrast changes) to improve model robustness, but it is a distinct step from core preprocessing tasks like handling missing values.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Performs Well in Training but Fails on New Experimental Data

Problem Description: Your model achieved high accuracy during training and validation on your initial dataset but shows significantly degraded performance when applied to new data from a different experiment, patient cohort, or laboratory.

Potential Causes & Solutions:

Cause: Data Drift and Non-Representative Training Data The training data was not representative of the real-world data the model encounters later. This is a fundamental failure of generalizability.

- Solution: Implement rigorous data provenance and representativeness analysis during preprocessing.

- Action: Before training, document the source and demographics of your training data. Use preprocessing steps to analyze feature distributions. If possible, incorporate diverse data sources from the start to create a more heterogeneous and representative training set [19].

- Preprocessing Technique: As part of your preprocessing pipeline, use tools to compare the distributions of key features between your training set and new, incoming data to detect "drift" [19].

- Solution: Implement rigorous data provenance and representativeness analysis during preprocessing.

Cause: Inconsistent Preprocessing Between Training and Inference Pipelines The data preprocessing steps applied to your training data were not identically applied to the new, incoming data.

- Solution: Standardize and version-control your preprocessing pipeline.

- Action: Package your preprocessing steps (imputation values, scaling parameters, encoding schemas) into a reusable pipeline or function. This ensures that every dataset fed to the model is transformed in exactly the same way [18]. Use data versioning tools (like lakeFS) to create immutable snapshots of both your raw data and the preprocessing code that acted upon it [18].

- Solution: Standardize and version-control your preprocessing pipeline.

Issue: Algorithm Fails to Converge or Training is Unstable

Problem Description: During the model training process, the algorithm's error does not consistently decrease, or the process is highly unstable.

Potential Causes & Solutions:

Cause: Improper Feature Scaling Many machine learning algorithms (e.g., SVMs, neural networks) are sensitive to the scale of input features. If features are on dramatically different scales, the model may struggle to converge.

- Solution: Apply feature scaling during preprocessing.

- Action: Normalize or standardize your numerical features. The choice of scaler depends on your data.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Split your data into training and test sets. Do not fit scalers on the entire dataset to avoid data leakage.

- Step 2: Fit the chosen scaler (e.g.,

StandardScalerfor Standardization,MinMaxScalerfor Normalization) on the training set only. - Step 3: Transform both the training and test sets using the parameters learned from the training set.

- Preprocessing Technique: The table below compares common scaling methods.

- Solution: Apply feature scaling during preprocessing.

Table: Common Feature Scaling Techniques

| Scaling Approach | Description | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Scaler | Centers data to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. | Data that is roughly normally distributed [18]. |

| Min-Max Scaler | Scales data to a fixed range, often [0, 1]. | Data that does not follow a normal distribution and where bounds are known [18]. |

| Robust Scaler | Scales using the interquartile range (IQR). It is robust to outliers. | Data containing significant outliers [18]. |

Cause: Presence of Outliers or Noisy Data Extreme values can dominate the model's loss function and prevent it from learning the central trends in the data.

- Solution: Identify and handle outliers during data cleaning.

- Action: Use statistical methods (e.g., IQR method, Z-scores) or visualization (e.g., box plots) to detect outliers.

- Preprocessing Technique: Decide whether to remove, cap, or transform outliers based on their presumed cause. If they are measurement errors, removal may be appropriate. If they are genuine but extreme biological responses, capping or using a Robust Scaler might be better [20].

- Solution: Identify and handle outliers during data cleaning.

The Data Preprocessing Workflow for Generalizable Models

The following diagram illustrates a robust, iterative preprocessing workflow that directly targets model generalizability, incorporating best practices from the cited literature.

Data Preprocessing Workflow for Generalizability

Workflow Stages:

- Data Audit & COU Definition: This is the foundational step. Precisely define the model's Context of Use and perform an initial audit of data sources, lineage, and representativeness against this COU [19].

- Data Cleaning: Address the common issues outlined in the troubleshooting guides: handle missing values (through imputation or removal), identify and treat outliers, and remove duplicate records [20] [18].

- Feature Engineering: Transform the data into a format suitable for modeling. This includes encoding categorical variables into numerical form, creating new features from existing ones, and scaling features to a uniform range [18].

- Data Splitting: Split the cleaned and engineered dataset into training, validation, and test sets. The test set must be held out and never used during training or preprocessing parameter tuning to provide an unbiased estimate of generalizability [18].

- Create Preprocessing Pipeline: Bundle all cleaning and transformation steps from steps 2 and 3 into a single, reusable pipeline. This ensures identical processing for training and future data, which is critical for generalizability [18].

- Train Model & Evaluate Generalizability: Train the model on the preprocessed training data and use the untouched test set for the final evaluation. Use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning. Monitor for performance drops that indicate overfitting or poor generalizability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for scFv Research and Development

| Research Reagent | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Single-chain Fragment variable (scFv) | The core recombinant antibody unit; a ~25 kDa polypeptide containing variable light (VL) and heavy (VH) chains connected by a flexible linker, serving as the primary antigen-binding element [23]. |

| Flexible Linker Peptide | A 15-20 amino acid peptide (often rich in glycine and serine) that connects the VL and VH domains, enabling proper folding and formation of the antigen-binding site [23]. |

| Phage Display Library | A key in vitro selection tool; a pooled library of scFvs displayed on bacteriophages used to screen for and select high-affinity binders without animal immunization [23]. |

| Bacterial Expression System | A standard, cost-effective system (e.g., E. coli) for producing scFvs. Requires strategies like periplasmic targeting or redox mutant strains for proper disulfide bond formation and solubility [23]. |

| Constant Domain Scaffold Vector | A plasmid vector used to convert a selected scFv back into a full-length monoclonal antibody by inserting the scFv's variable domains into the scaffold [23]. |

| Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) Vector | A genetic construct that fuses an scFv (for antigen recognition) to T-cell receptor signaling domains, used to create CAR-T cells for immunotherapy [23]. |

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to scFM Data Preprocessing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is tokenization in the context of single-cell genomics, and why is it a critical step? Tokenization is the process of converting raw, unstructured data into discrete units called "tokens" that a model can process. For single-cell data, this typically involves defining genes or genomic features as the fundamental tokens, and the combination of these tokens represents a single cell, analogous to words forming a sentence [1]. This step is critical because it standardizes the biological data into a structured format that deep learning architectures, particularly transformers, can understand and learn from. The chosen tokenization strategy directly impacts the model's ability to capture biological patterns, its scalability, and its performance on downstream tasks [24].

FAQ 2: My model is struggling with the non-sequential nature of gene expression data. What are the common strategies to impose an order? Unlike words in a sentence, genes in a cell have no inherent sequence. To apply sequence-based models like transformers, researchers use deterministic strategies to create an order. Common methods include:

- Ranking by Expression: Sorting genes within each cell by their expression levels (from highest to lowest) and using the ordered list of top genes as the input sequence [1] [2].

- Expression Binning: Partitioning genes into bins based on their expression values and using these bins to determine their position in the sequence [1].

- Fixed Gene Order: Some models forgo complex ranking and simply use a fixed, pre-defined order for all genes, relying on normalized counts [1].

FAQ 3: During fine-tuning, my model performs well on some tasks but fails on others that require broader sequence context. What could be the issue? This is a known challenge. Some tokenization strategies, particularly those using overlapping k-mers, may lead the model to learn the identity of individual tokens very well but struggle to capture larger sequence context [25]. If your fine-tuning task relies heavily on long-range dependencies within the data (e.g., understanding regulatory networks across the genome), the foundation model's tokenization might be a bottleneck. It is recommended to use benchmarking tasks that are independent of specific biology to evaluate the model's ability to learn sequence context, such as next-token prediction without overlaps [25].

FAQ 4: How can I enrich my token inputs to provide more biological context to the model? Beyond the raw gene identifier and expression value, you can incorporate additional biological metadata as special tokens or within the token embedding. This can include:

- Cell-level context tokens representing the cell's identity or metadata [1].

- Modality indicators for multi-omics models (e.g., scRNA-seq vs. scATAC-seq) [1].

- Gene metadata such as Gene Ontology terms or chromosomal location [1].

- Batch information to help the model account for technical variations [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Model Generalization Across Different Datasets

Symptoms: The model performs well on the training data or data from similar batches but shows significantly degraded performance on new datasets with different technical characteristics.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: High sensitivity to batch effects.

- Solution: Incorporate batch information directly into the tokenization process using special batch tokens [1]. This allows the model to explicitly learn and adjust for technical variations.

- Cause: Inadequate data diversity during pre-training.

- Solution: Ensure your pre-training corpus is assembled from high-quality, diverse datasets that span multiple biological conditions, tissues, and species. Leverage curated public archives like CZ CELLxGENE, the Human Cell Atlas, and GEO to maximize biological variation [1].

- Cause: Overfitting to the token sequence rather than learning biological context.

- Solution: Consider using a tokenization strategy that encourages learning of broader context. Interrogate your model's learning through tasks like non-overlapping next-token prediction to diagnose an over-reliance on token identity [25].

Problem 2: Inefficient Training or Out-of-Memory Errors

Symptoms: Training is prohibitively slow, or the process fails due to insufficient GPU memory, especially with long gene sequences.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overly long input sequences due to a large number of genes.

- Cause: Suboptimal tokenization strategy creating excessive tokens.

- Solution: Evaluate different tokenization methods. While treating every gene as a token is common, other strategies like non-overlapping k-mers or Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) can be more computationally efficient for certain architectures [24].

- Cause: Standard transformer self-attention mechanism has high computational complexity.

- Solution: Explore more efficient model architectures like HyenaDNA or Mamba, which are designed to handle very long sequences (up to 1 million tokens) more efficiently than standard transformers [24].

Problem 3: Low Interpretability of Model Results

Symptoms: The model makes accurate predictions, but it is difficult to understand which genes or features drove the decision, limiting biological insight.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The "black box" nature of deep learning models, particularly transformers.

- Solution: Leverage the model's attention mechanisms. Analyze the attention weights to identify which genes the model "attended to" most strongly when making a prediction. This can reveal important gene-gene relationships [1].

- Cause: Token embeddings are not biologically meaningful.

- Solution: Extract and analyze the contextualized token embeddings. Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can be used to assess whether the embeddings capture biological structure, such as grouping genes with similar functions [25].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Gene-Ranking Tokenization for scRNA-seq Data

This is a common method for preparing single-cell RNA sequencing data for transformer models.

- Input: A raw count matrix (cells x genes).

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells and genes with low expression across the dataset.

- Normalization: Normalize the count data (e.g., using log(CP10K+1)) to account for differences in sequencing depth.

- Gene Selection: Select the top 2,000-4,000 highly variable genes. Alternatively, for a per-cell approach, use all genes that are expressed in that cell.

- Ranking: For each individual cell, rank all selected genes by their normalized expression value from highest to lowest.

- Sequencing: Create the input sequence for the cell by using the ordered list of gene identifiers. The sequence length can be truncated to a fixed number (e.g., the top 1,000 genes) for uniformity [1] [2].

- Embedding: Each gene ID in the sequence is converted into a trainable embedding vector. The expression value can be incorporated as a separate value or integrated into the embedding.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Sequence Context Learning with Non-Overlapping Next-Token Prediction

This protocol provides a task-agnostic method to evaluate how well a foundation model learns sequence context beyond simple token identity [25].

- Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained DNA or single-cell foundation model to evaluate.

- Task Formulation: Fine-tune the selected model to predict the next k-mer in a sequence, where the k-mer does not overlap with the input context tokens.

- For example, given a sequence window, mask the next 3 nucleotides (a non-overlapping 3-mer) and train the model to predict it.

- Dataset: Prepare a held-out genomic or single-cell sequence dataset not seen during pre-training.

- Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the model on this next-token prediction task.

- Evaluation: Measure the prediction accuracy on a test set. A model that has learned meaningful sequence context will achieve accuracy significantly higher than random chance (e.g., >0.25 for a 4-mer, compared to a random baseline of 0.004). Poor performance indicates the model may be over-reliant on token identity and struggles with broader context [25].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Common Tokenization Techniques in Genomics

| Tokenization Method | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Example Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-Hot Encoding | Each nucleotide (A,C,G,T) is represented as a binary vector. | Simple, interpretable, no information loss. | Results in very long, sparse sequences; does not scale well to long sequences. | DeepBind, Basset, Enformer [24] |

| Non-overlapping k-mers | Sequence is broken into consecutive, non-overlapping blocks of k nucleotides. |

Reduces sequence length, can capture short motifs. | May break up biologically meaningful motifs that span across tokens. | Nucleotide Transformer [24] |

| Overlapping k-mers | Sequence is broken into blocks of k nucleotides that slide one nucleotide at a time. |

Preserves local context and mitigates motif splitting. | Creates a larger number of tokens, increasing computational cost; may limit learning of long-range context [25]. | DNABERT [24] [25] |

| Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) | A data compression algorithm adapted to find the most frequent "words" in a sequence. | Data-driven; can learn meaningful, recurring biological motifs. | Can be computationally intensive to train; learned tokens may not be biologically interpretable. | DNABERT-2 [24] |

| Gene-based Tokenization | Each gene or genomic feature is treated as a unique token. | Directly models gene-level interactions, ideal for scRNA-seq. | Requires imposing an artificial order on genes; loses nucleotide-level resolution. | scGPT, Geneformer [1] [2] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scFM Development

| Item | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|

| Curated Single-Cell Atlases (e.g., CZ CELLxGENE, Human Cell Atlas) | Provide large-scale, diverse, and often annotated datasets essential for pre-training robust foundation models [1]. |

| Unified Data Frameworks (e.g., BioLLM) | Offer standardized APIs and documentation to integrate, apply, and benchmark different scFMs, streamlining research and ensuring consistent evaluation [2]. |

| Deep Learning Libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) | Provide the core programming environment and tools for building, training, and fine-tuning complex model architectures like transformers [26]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources (GPUs/TPUs) | Necessary to handle the immense computational and memory demands of training and running large-scale foundation models on massive datasets [26]. |

Workflow Visualizations

Tokenization Workflow for scFMs

Troubleshooting Poor Generalization

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why do I get different gene lists when using different ranking criteria (like p-value vs. fold-change)?

Different criteria measure distinct aspects of differential expression. The p-value assesses the statistical significance of an observed difference, considering both the effect size and its variability. In contrast, the fold-change measures the magnitude of the difference in expression levels between conditions without accounting for variance. A gene with a small fold-change can have a very small p-value if its standard deviation is tiny, and a gene with a large fold-change can have a large p-value if its variance is high. These fundamental differences often lead to incompatible gene lists [27].

FAQ 2: What can I do if my gene ranking is unstable due to noisy data or small sample sizes?

Unstable rankings, where the estimated effect sizes or their standard deviations are noisy, are common with small or moderate sample sizes (e.g., less than 20 per group). To address this, consider using a hierarchical model that shares information across genes. This approach can stabilize estimates of variance and effect size, leading to more reliable and powerful rankings. For large datasets (e.g., over 10,000 genes), this is still practical using modern optimization techniques [28].

FAQ 3: How should I choose a color scale for visualizing my gene expression data?

The choice of color scale is critical for honest and effective communication. Follow these key principles:

- Use Perceptually Uniform Color Spaces: Employ color spaces like CIE Luv or CIE Lab, where a unit change in color corresponds to a uniform change in human perception [29].

- Map High Values to Darker Colors: For typical gene expression data with many zeros and a long tail of high values, map low expression to light colors and high expression to dark colors. This prevents the few high-expression data points from being visually washed out by the many low-expression points [30].

- Ensure Accessibility: Test your color scales for color deficiencies (e.g., Deuteranopia, Protanopia). Avoid red-green schemes and use tools to simulate how your visuals will appear [29] [31].

FAQ 4: My experiment has multiple factors (e.g., treatment and time). How can I create a single gene list that accounts for both?

Instead of generating separate gene lists for each factor, you can use multi-criteria layer ranking algorithms. Methods like point-admissible, line-admissible (convex), and Pareto ranking allow you to combine rankings from different statistical tests (e.g., for treatment effect and time effect) into a single, unified preference list. This helps prioritize genes that respond to multiple experimental factors simultaneously [27].

FAQ 5: Beyond simple ranking, how can I frame the problem of selecting genes for follow-up experiments?

Shift the framework from a binary "effect yes/no" decision (common with False Discovery Rate) to a ranking under cost constraints. Since follow-up experiments are resource-intensive, the goal is to prioritize genes where you have high confidence that something interesting is happening. One practical approach is to define a minimum biologically interesting effect size and then rank genes by their posterior probability of having an effect larger than this threshold [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Power and High False Discovery Rate in Ranking

Problem: Your differential expression analysis fails to detect known true positives (low power) or selects many false positives (high FDR), especially when detecting small fold-changes.

Solution: For experiments with small or moderate sample sizes, a two-dimensional convex layer ranking that jointly considers both p-value and fold-change can outperform standard p-value ranking. This method has been shown to achieve generally lower FDR and higher power under these conditions [27].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Layer Ranking

- Compute Univariate Rankings: For your dataset, calculate the fold-change (FC) and p-value (P-val) for each gene between two conditions.

- Apply a Layer Ranking Algorithm:

- Point-Admissible Ranking: Identifies genes that are top-ranked by at least one individual criterion.

- Convex (Line-Admissible) Ranking: Ranks genes based on their performance on a convex line combining the multiple criteria (e.g., p-value and fold-change).

- Pareto Ranking: Identifies genes that are non-dominated, meaning no other gene is better on all criteria.

- Generate a Unified List: The layer ranking algorithm provides a single, preference-ordered gene list that balances the multiple criteria [27].

The workflow below illustrates the process of creating a unified gene list from multiple ranking criteria.

Issue 2: Unstable Gene Ranking from Noisy Estimates

Problem: Rankings based on metrics like mean(case_vs_control) / sd(case_vs_control) are unstable because the standard deviation (sd) can be noisy, especially for low-expression genes.

Solution: Implement a hierarchical (multilevel) model that partially pools variance estimates across genes. This shrinkage produces more stable estimates of variability, leading to more reliable rankings. This Bayesian approach is feasible even for large-scale genomic data (e.g., >10k genes) using optimizers or approximate inference methods [28].

Experimental Protocol: Hierarchical Modeling for Stable Ranking

- Model Specification: Define a model where gene expression counts (e.g., for RNA-seq) are modeled with an appropriate likelihood (e.g., Negative Binomial). Place hierarchical priors on gene-specific parameters like log-fold-changes and dispersions.

- Incorporate Trends: A common domain-specific tweak is to model the trended relationship between a gene's mean expression and its dispersion.

- Model Fitting: Use statistical software (e.g.,

rstanarmin R) capable of fitting hierarchical models. For very large datasets, use an optimizer to find the posterior mode, or tools like ADVI or Pathfinder for faster approximation. - Extract Rankings: Rank genes based on the shrunken posterior estimates of the log-fold-change or by the posterior probability that the fold-change exceeds a meaningful threshold [28].

The following workflow contrasts the standard approach with the more stable hierarchical modeling method.

Data Presentation and Visualization

Table 1: Comparison of Gene Ranking Criteria and Their Properties

| Ranking Criterion | What It Measures | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold-Change (FC) | Magnitude of expression difference between two conditions [27] | Intuitive; easy to compute and interpret | Does not account for variability; genes with high variance can show large FC by chance [27] | Initial, quick screening of large effect sizes |

| P-value | Statistical significance of the observed difference (combining effect size and variance) [27] | Accounts for within-gene variability; well-established inference framework | Can select genes with very small, biologically irrelevant fold-changes if variance is tiny [27] | Identifying statistically significant changes when effect size variability is a key concern |

| Frequency of Selection (e.g., by SVM-RFE) | How often a gene is selected as a predictive feature during cross-validation [27] | Directly tied to predictive power for sample classification; robust against overfitting | Computationally intensive; may not select biologically relevant but weakly predictive genes | Building robust classifiers for phenotype prediction |

| Bayes Factor | Evidence for a model including a condition effect vs. a model without it [28] | Provides a continuous measure of evidence; allows for direct probability statements | Highly sensitive to the choice of prior distribution; can be computationally challenging [28] | Comparing well-specified models where prior information is available and justified |

| Posterior Probability of Effect | Probability that the absolute fold-change exceeds a pre-specified, biologically relevant threshold [28] | Directly addresses the question of practical significance; intuitive interpretation | Requires defining a meaningful effect size threshold | Prioritizing genes for follow-up studies where cost constraints are known |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Their Functions in Gene Ranking Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function / Role | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Differential Expression Analysis [28] | Industry-standard software packages for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. They use statistical models to test for significance and can provide shrunken estimates of fold-changes. |

| rstanarm | Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling [28] | An R package that provides an interface to the Stan probabilistic programming language. It allows fitting hierarchical models for genomic data to achieve more stable rankings. |

| HCL Wizard | Perceptually Uniform Color Scheme Generation [31] | An online tool for creating color scales in the Hue-Chroma-Luminance (HCL) color space, which is perceptually uniform. Essential for generating accessible and honest visualizations of gene expression. |

| PertEval-scFM | Benchmarking Framework for Single-Cell Foundation Models [32] | A standardized framework for evaluating how well single-cell foundation model (scFM) embeddings perform on tasks like perturbation effect prediction, providing a benchmark for model performance. |

| Layer Ranking Algorithms (Point-Admissible, Convex, Pareto) | Multi-Criteria Decision Making [27] | A class of algorithms designed to merge multiple ranked gene lists (e.g., from p-value, fold-change, etc.) into a single, unified preference list that balances all criteria. |

| Color Blindness Simulator (Coblis) | Accessibility Checking [31] | A tool to simulate how your chosen color scales will appear to individuals with various types of color vision deficiencies (e.g., Protanopia, Deuteranopia), ensuring your visuals are inclusive. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary purpose of tokenization in a single-cell Foundation Model (scFM)?

- A: Tokenization converts raw, unstructured omics data into a structured sequence of discrete units (tokens) that the model can understand and process. It standardizes diverse data types, like gene expression counts or chromatin accessibility peaks, into a common format, enabling the transformer architecture to learn the complex relationships between genes, cells, and modalities [1].

Q2: My data comes from different technologies (e.g., scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq). How can I represent them in a single model?

- A: You can incorporate special modality tokens at the beginning of each cell's sequence to indicate the data source (e.g.,

[RNA]or[ATAC]). This allows the model to learn both modality-specific and shared patterns across your datasets [1]. For example, the input sequence for a cell could be:[RNA] [CELL_ID] Gene_A Gene_B ...

- A: You can incorporate special modality tokens at the beginning of each cell's sequence to indicate the data source (e.g.,

Q3: How should I handle critical metadata, such as sample batch, donor, or treatment, in the tokenization process?

- A: Metadata can be added as special tokens to provide rich context. For instance, you can prepend a

[BATCH_1]or[TREATED]token to a cell's sequence. This helps the model condition its predictions on this information and can significantly aid in learning batch-invariant biological representations [1].

- A: Metadata can be added as special tokens to provide rich context. For instance, you can prepend a

Q4: Is there a standard way to order genes or features before tokenization?

- A: No, this is an active area of development. Since omics data has no inherent sequence, common strategies include ranking genes by their expression level within each cell, binning genes by expression values, or simply using a fixed, pre-defined order (e.g., alphabetical by gene symbol). Some models report robustness across different ordering schemes [1].

Q5: What are the consequences of poor tokenization on my scFM's performance?

- A: Ineffective tokenization can introduce noise and bias, leading to several downstream issues:

- Poor Generalization: The model may fail to perform well on new, unseen datasets.

- Failure to Integrate: The model might be unable to harmonize data from different modalities or batches.

- Reduced Interpretability: The latent representations learned by the model may not correspond to clear biological concepts [1] [33].

- A: Ineffective tokenization can introduce noise and bias, leading to several downstream issues:

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor cross-dataset performance | Inconsistent tokenization between pretraining and fine-tuning datasets; high batch effect. | Standardize gene identifier nomenclature (e.g., all ENSEMBL IDs). Incorporate batch information as a metadata token and use techniques like strategic data sourcing to ensure training data diversity [1]. |

| Model fails to distinguish data types | Missing or incorrect modality tokens for multi-omics data. | Explicitly prepend a modality-specific token (e.g., [ATAC], [PROTEIN]) to the input sequence of every cell. Verify that these tokens are correctly parsed during data loading [1]. |

| Training is unstable or slow | Highly variable sequence lengths due to a large number of features per cell. | Implement a consistent feature selection strategy. For example, use the top N highly variable genes or filter features by minimum expression. This creates uniform input dimensions and improves training efficiency [1]. |

| Model ignores metadata context | Metadata tokens are not properly leveraged during the self-supervised pretraining task. | Use a pretraining objective that forces the model to use metadata. Instead of only predicting masked genes, add a secondary task to classify or reconstruct the metadata token itself [1]. |

| Inability to reproduce published benchmarks | Differences in the tokenization pipeline (e.g., gene ordering, normalization, missing value handling). | Meticulously replicate the tokenization method described in the original paper. If details are missing, check for publicly released code. Consider using a unified platform like BioLLM or scGPT for a standardized starting point [33]. |

Experimental Protocols for Tokenization

Protocol 1: Basic Tokenization for scRNA-seq Data

This protocol outlines the steps to convert a single-cell RNA-seq count matrix into token sequences suitable for a transformer model.

- Input: A cell-by-gene count matrix.

- Quality Control & Filtering: Filter out low-quality cells (based on metrics like UMI counts, mitochondrial gene percentage) and genes not expressed in a sufficient number of cells.

- Normalization: Normalize the count data (e.g., using log1p transformation after library size normalization) to account for varying sequencing depths.

- Feature Selection: Select the top N highly variable genes to focus the model on the most informative features and reduce computational load.

- Gene Ordering: For each cell, create a sequence by ordering the selected genes based on a deterministic rule. A common method is to rank genes by their normalized expression value in descending order for that specific cell.

- Token Creation:

- Each gene in the sequence is represented as a token. The token can combine the gene's identifier (e.g.,

ENSG00000139618) and its normalized value, or the value can be added as a separate input embedding. - Prepend a special

[CLS]token to the sequence. The final hidden state corresponding to this token is often used as the aggregate representation for the entire cell [1].

- Each gene in the sequence is represented as a token. The token can combine the gene's identifier (e.g.,

Protocol 2: Advanced Tokenization for Multi-Modal Data

This protocol extends Protocol 1 to incorporate data from multiple omics layers.

- Input: Multiple cell-by-feature matrices (e.g., from scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, and protein abundance).

- Modality-Specific Preprocessing: Independently preprocess each modality using appropriate methods (e.g., term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) for scATAC-seq data).

- Feature Selection per Modality: Perform feature selection within each modality (e.g., highly variable genes for RNA, top accessible peaks for ATAC).

- Token Sequence Construction:

- For each cell, create a separate sequence for each modality.

- At the start of each modality's sequence, prepend a special modality token (e.g.,

[RNA],[ATAC],[ADT]). - Optionally, prepend a global metadata token for information like

[BATCH_A]or[DONOR_1]. - The final input sequence for a cell is constructed by concatenating these sequences. For example:

[BATCH_A] [RNA] Gene_XYZ Gene_ABC ... [ATAC] Peak_123 Peak_456 ...[1] [33].

- Positional Encoding: Apply standard transformer positional encodings to the entire concatenated sequence to inform the model about the order of tokens.

The following diagram illustrates this multi-modal tokenization workflow.

Quantitative Data on Tokenization and Model Performance

The table below summarizes key metrics from recent studies that highlight the impact of data scale and tokenization strategies on scFM performance.

Table 1: Impact of Training Scale and Tokenization on Model Performance

| Model / Study | Pretraining Corpus Size | Key Tokenization Strategy | Reported Outcome / Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT [33] | 33 million cells | Ranking genes by expression; use of special tokens for cell identity. | Exceptional cross-task generalization; enabled zero-shot cell type annotation and perturbation prediction. |

| Nicheformer [33] | 110 million cells | Not explicitly detailed, but uses graph transformers for spatial data. | Set record for processed dataset size; robust zero-shot capabilities in novel biological contexts. |

| scPlantFormer [33] | Not specified | Integration of phylogenetic constraints into the attention mechanism. | 92% cross-species cell annotation accuracy in plant systems. |

| General Finding [1] | Tens of millions of cells (across public archives) | Use of a dedicated cell-level token. | The final hidden state of this token serves as a powerful, aggregated representation for the entire cell. |

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for scFM Tokenization and Training

| Item / Resource | Function in the Tokenization & Training Pipeline |

|---|---|

| CZ CELLxGENE Discover [1] [33] | Provides unified access to tens of millions of curated, annotated single-cells; essential for sourcing diverse pretraining data. |

| scGPT / BioLLM [33] | Offers open-source frameworks and universal interfaces for benchmarking scFMs, providing reference implementations for tokenization. |

| Transformer Architecture [1] | The core neural network backbone that processes token sequences using self-attention to model relationships between all tokens. |

| Hugging Face Ecosystem [33] | A model-sharing platform; the review notes a need for a similar, sustainable infrastructure for sharing and versioning scFMs. |

| Standardized Gene Identifiers (e.g., ENSEMBL) | Crucial for aligning features across different datasets during the tokenization process to ensure consistent model input. |

The following diagram maps the logical relationship between data sources, tokenization steps, model training, and downstream applications, providing a high-level overview of a complete scFM pipeline.

Data Integration and Batch Correction Techniques for Diverse Datasets

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary goal of data integration in single-cell analysis for foundation model training?

The primary goal is to combine data from diverse sources, such as different experiments, technologies, or batches, into a unified and standardized format. This process is crucial for creating a high-quality training corpus for single-cell foundation models (scFMs), allowing them to learn universal biological patterns rather than dataset-specific technical artifacts. Effective integration mitigates batch effects—systematic non-biological variations that can compromise data reliability and obscure genuine biological signals [34] [35].

Q2: Why are batch effects particularly problematic for scRNA-seq data, and how can I detect them?

Batch effects are problematic because they can be on a similar scale, or even larger, than the biological differences of interest, severely reducing the statistical power to detect truly differentially expressed genes [36]. You can detect them through visualization techniques like UMAP plots; if cells cluster strongly by batch (e.g., by sequencing run or laboratory) rather than by biological cell type or condition, it indicates a significant batch effect that requires correction [37].

Q3: My scFM is performing poorly on a downstream task like cell type annotation. Could data preprocessing be the issue?

Yes, data preprocessing is a likely culprit. The performance of scFMs is highly dependent on the quality and consistency of the input data. Key issues to investigate include:

- Inadequate Batch Correction: Persistent batch effects can confuse the model. Consider using a more robust correction method like ComBat-ref, which has been shown to improve sensitivity in differential expression analysis [36].

- Inconsistent Tokenization: scFMs require genes to be represented as tokens. If your preprocessing pipeline uses a different gene ranking or normalization strategy than what the model was pretrained on, it can lead to suboptimal performance [35].

- Low Data Quality: High levels of ambient RNA or mitochondrial reads in your training data can obscure biological signals. Rigorous quality control is essential [34] [37].

Q4: When should I use a complex scFM versus a simpler baseline model for my analysis?

The choice depends on your specific task, dataset, and resources. Benchmarking studies reveal that:

- scFMs are robust and versatile tools for diverse applications, especially when you need to leverage knowledge learned from massive datasets. They excel in zero-shot learning and can be efficiently adapted with fine-tuning [34] [2].

- Simpler machine learning models (e.g., Seurat, Harmony, scVI) can be more adept at efficiently adapting to specific, smaller datasets, particularly under computational resource constraints [34]. Notably, no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, so selection should be tailored based on factors like dataset size and task complexity [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Data Integration After Applying Batch Correction

Symptoms:

- Cells in UMAP or t-SNE plots still cluster strongly by batch after correction.

- Poor mixing of cells from different datasets in the latent space of your scFM.

- Low accuracy in cross-dataset cell type annotation.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Check Data Quality and Normalization:

- Ensure that all datasets have undergone rigorous quality control (removing low-quality cells, doublets, and ambient RNA) and consistent normalization before attempting batch correction [37].

- Confirm that the same gene annotation (e.g., Ensembl IDs) is used across all datasets.

Re-evaluate Your Batch Correction Method:

- Some methods may be better suited for your specific data. Consider trying a method that uses a reference batch. For example, ComBat-ref selects the batch with the smallest dispersion as a reference and adjusts other batches towards it, which has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in RNA-seq data [36].

- For complex integrations (e.g., across different tissues or species), ensure your method is designed to handle such biological variation and not just technical noise.

Assess Model Selection:

- If using an scFM for integration, consult benchmark studies to choose a model strong for your task. For instance, some scFMs like scGPT show robust performance across various tasks, while others like Geneformer excel in gene-level tasks [2]. Frameworks like BioLLM can provide a standardized way to compare different models [2].

Issue 2: scFM Fails to Capture Biologically Meaningful Representations

Symptoms:

- The model's cell embeddings do not separate known cell types.

- Attention mechanisms do not highlight genes with known biological relevance to the cell state.

- Poor performance on a knowledge-based evaluation metric like scGraph-OntoRWR, which measures the consistency of captured cell-type relationships with established biological ontologies [34].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Verify Tokenization Strategy:

- scFMs convert gene expression data into tokens. A common challenge is that genes have no natural order. Most models impose one, such as ranking by expression level within each cell [35] [1]. Ensure your data preprocessing matches the tokenization strategy (e.g., gene ranking, value binning) used during the scFM's pretraining.

- Check if the model expects special tokens for cell metadata or batch information and include them if required [35].

Investigate Pretraining Data Mismatch:

- The scFM may not have been pretrained on data similar to yours. Check the model's documentation. If your cell type or tissue is underrepresented, consider fine-tuning the model on a relevant, high-quality dataset.

- The diversity of pretraining data is critical. Models trained on larger, more diverse atlases (e.g., from CELLxGENE) generally capture better biological representations [34] [35].

Evaluate with Biology-Driven Metrics:

- Move beyond standard accuracy metrics. Use evaluations like the Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD), which measures the ontological proximity between misclassified cell types, to ensure errors are biologically plausible [34].

- Analyze the "roughness" of the latent space; a smoother landscape often correlates with better task performance and can be a useful proxy for model selection [34].

Issue 3: High Computational Demand and Long Training Times

Symptoms:

- Fine-tuning an scFM on a new dataset takes prohibitively long.

- The model requires more GPU memory than is available.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Optimize Input Data:

Leverage Transfer Learning Efficiently:

- For specific tasks, start with the pretrained model's embeddings and train a simpler, task-specific classifier on top, rather than fine-tuning the entire massive model.

- Explore parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods if supported by the model.

Consider Alternative Models:

- If resources are extremely constrained, benchmark simpler baseline models (e.g., scVI, Seurat) against scFMs for your specific task. As noted in benchmarks, simpler models can sometimes outperform scFMs on specific datasets with far less computational overhead [34].

Quantitative Data and Method Comparisons

Performance of scFMs and Baseline Methods Across Key Tasks

The following table summarizes findings from a comprehensive benchmark study evaluating six scFMs against established baseline methods. Performance is a holistic ranking based on multiple metrics [34].

| Model Category | Example Models | Batch Integration | Cell Type Annotation | Gene-Level Tasks | Clinical Task (e.g., Drug Sensitivity) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Foundation Models (scFMs) | scGPT, Geneformer, scFoundation | Robust and versatile [34] | Strong in zero-shot [34] [35] | Geneformer, scFoundation excel [2] | Promising for clinical insight [34] | Captures universal biological knowledge; transferable to many tasks. |

| Generative Baseline | scVI | Effective for integration [34] | Good performance [34] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Probabilistic modeling of count data. |

| Clustering-Based Baseline | Harmony | Effective for integration [34] | Good performance [34] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Efficient for correcting embeddings. |

| Anchor-Based Baseline | Seurat | Effective for integration [34] | Good performance [34] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Widely adopted; strong community support. |

Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Methods for RNA-seq Data

This table compares the performance of various batch correction methods, based on a study that introduced ComBat-ref [36]. Performance was measured using True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR) in detecting differentially expressed genes after correction.

| Method | Underlying Model | Key Feature | Performance with High Batch Dispersion | Preserves Count Data? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-ref | Negative Binomial GLM | Selects lowest-dispersion batch as reference | High TPR, controlled FPR [36] | Yes [36] |

| ComBat-seq | Negative Binomial GLM | Uses an average dispersion for adjustment | Lower TPR vs. ComBat-ref [36] | Yes [36] |