Cell Death in Culture: Mechanisms, Detection, and Strategies for Bioprocess Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with mammalian cell cultures.

Cell Death in Culture: Mechanisms, Detection, and Strategies for Bioprocess Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with mammalian cell cultures. It explores the fundamental molecular mechanisms of regulated cell death—including apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis—and their critical impact on biopharmaceutical production and research outcomes. The scope extends from foundational knowledge to advanced methodological applications, detailing current and emerging biomarkers and detection techniques such as flow cytometry and ELISA. The content further offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to inhibit cell death in bioreactors, such as genetic engineering with anti-apoptotic genes and media supplementation. Finally, it addresses the validation and comparative analysis of cell death modalities, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for improving yield in bioprocessing and therapeutic development.

Understanding Cell Death: Fundamental Mechanisms and Morphological Hallmarks

Foundational Concepts: What is Regulated Cell Death?

What is the fundamental difference between Accidental Cell Death (ACD) and Regulated Cell Death (RCD)?

ACD is an uncontrollable, instantaneous process caused by extreme physical, chemical, or mechanical insults, such as ischemia or freeze-thaw cycles, leading to uncontrolled cell destruction [1]. In contrast, RCD is a finely tuned process activated by specific signal transduction pathways and is controllable by genetic or pharmacological intervention [2] [1]. This controllability makes RCD a key target for therapeutic development.

How does Programmed Cell Death (PCD) relate to RCD?

PCD is a subtype of RCD that occurs during embryonic development and tissue homeostasis, a physiological form of death not directly linked to external disturbances [1]. RCD is a broader term that also includes pathways activated in response to stress or perturbations of the cellular environment, such as during infection or toxin exposure [2] [1].

What are the key morphological features distinguishing different RCD pathways?

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the most well-studied RCD pathways.

| RCD Pathway | Morphological Hallmarks | Core Mediators/Executioners | Immunological Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis [2] [3] | Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, membrane blebbing, formation of apoptotic bodies [4]. | Caspase-3, -7 (executioners); Caspase-8, -9 (initiators); BCL-2 family proteins [2] [3]. | Immunologically silent; no inflammation [2] [4]. |

| Pyroptosis [2] [4] | Rapid plasma membrane rupture, cytoplasmic swelling, release of proinflammatory intracellular contents [4]. | Gasdermin D (GSDMD) pore formation; Caspase-1, -4, -5, -11 [2]. | Inflammatory; releases potent inflammatory mediators [2]. |

| Necroptosis [2] [4] | Cytoplasmic swelling (oncosis), organelle dilation, plasma membrane rupture [4]. | RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL pore formation [2] [4]. | Inflammatory; releases alarmins and other proinflammatory signals [4]. |

| Ferroptosis [2] | Accompanied by iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation [2]. | Molecular executioners not fully defined; characterized by iron-dependent phospholipid peroxide accumulation [2] [5]. | Inflammatory [2]. |

What is PANoptosis?

PANoptosis is a unified, multifaceted cell death pathway that integrates components from pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis [2]. It is characterized by the simultaneous activation of biochemical markers from these three pathways in response to specific triggers, such as viral or bacterial infection [2]. The combined loss of key regulators from all three pathways is required to prevent this cell death, which is not achievable by targeting any single pathway alone [2].

Detection and Methodologies

What are the primary assays for detecting apoptosis in my cell cultures?

Apoptosis detection requires multiple assays to capture its multi-stage complexity [3]. The table below organizes key methodologies based on their detection target.

| Detection Target | Assay/Method | Key Reagents & Kits | Technical Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Changes (Early Apoptosis) | Annexin V / Propidium Iodide (PI) staining [3]. | Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (e.g., Thermo Fisher Scientific) [6]. | Distinguishes early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) cells [3]. |

| DNA Fragmentation (Late Apoptosis) | TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling) assay [3]. | Commercial TUNEL assay kits. | Labels 3'-OH ends of fragmented DNA; detectable by flow cytometry or microscopy [3]. |

| Caspase Activation | Fluorogenic substrate cleavage or fluorescent inhibitor binding [3]. | Caspase-3, -8, -9 activity assay kits. | Measures activity of initiator and executioner caspases [3]. |

| Mitochondrial Alterations | Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) loss [3]. | JC-1, TMRM, TMRE dyes [3]. | Shift in JC-1 fluorescence from red (aggregates) to green (monomers) indicates ΔΨm loss [3]. |

| Cytomorphological Changes | Fluorescence microscopy with DNA-binding dyes [3]. | DAPI, Hoechst stains [3]. | Visualizes chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation [3]. |

Could you provide a detailed protocol for flow cytometry-based apoptosis detection using Annexin V/PI?

This protocol is a cornerstone for quantifying cell death in culture.

- 1. Cell Preparation: Harvest adherent cells using a gentle, non-enzymatic dissociation buffer (e.g., EDTA-based) to preserve phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet. Wash cells once with cold PBS.

- 2. Staining: Resuspend ~1x10^5 cells in 100 µL of 1X Annexin V Binding Buffer. Add Annexin V-fluorochrome conjugate (e.g., FITC) and incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature (25°C) in the dark [3].

- 3. Propidium Iodide Addition: Add PI to the staining mixture immediately before analysis. Note: Some protocols recommend adding PI simultaneously with Annexin V.

- 4. Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze cells on a flow cytometer within 1 hour. Use appropriate lasers and filters for your chosen fluorochromes.

- Data Interpretation:

- Annexin V-/PI-: Viable, healthy cells.

- Annexin V+/PI-: Early apoptotic cells.

- Annexin V+/PI+: Late apoptotic or necrotic cells.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

My primary cells are dying unexpectedly in culture. What are the common culprits?

Unexpected cell death is often linked to culture technique, incubation conditions, and media [7].

- Technique: Uneven handling, insufficient mixing of the cell inoculum, or excessive pipetting can create foam or bubbles that hinder cell attachment and growth [7]. Static electricity in low-humidity environments can also disrupt cell attachment to plastic vessels [7].

- Incubation: Repeatedly opening the incubator causes temperature fluctuations and evaporation, which severely affect growth rate and viability [7]. Ensure water reservoirs are full to maintain humidity. Vibration from loose incubator fans or external sources can cause unusual, concentric cell growth patterns [7].

- Media: Media defects are not always visible. Test by comparing your current media with a batch from a different manufacturer. Issues can arise from insufficient reagent quality, incorrect pH buffering, or inadequate filtration [7].

My apoptosis assay shows high background necrosis. How can I mitigate this?

High necrosis often indicates excessive cellular stress during the experiment.

- Optimize Handling: Use gentle cell harvesting techniques. Avoid trypsinization for extended periods; use enzyme-free cell dissociation buffers instead.

- Confirm Treatment Specificity: Ensure your death-inducing agent is not causing overwhelming, nonspecific toxicity. Perform a dose-response curve to find a concentration that reliably induces regulated death without causing accidental lysis.

- Timing is Critical: Analyze your cells at the appropriate time point after inducing death. If you wait too long, apoptotic cells will undergo secondary necrosis, confounding your results [4].

I am detecting markers for multiple RCD pathways. Is this possible?

Yes. Mounting genetic and biochemical evidence shows remarkable flexibility and crosstalk among RCD pathways [2]. This interconnectedness is the basis for the concept of PANoptosis [2]. For example, Caspase-8 is a crucial molecular switch that can promote apoptosis or, when its activity is inhibited, shift the cell toward necroptosis [4]. Detecting overlapping markers suggests a complex, integrated cell death response, which may be the intended physiological outcome in response to specific triggers like viral infection [2].

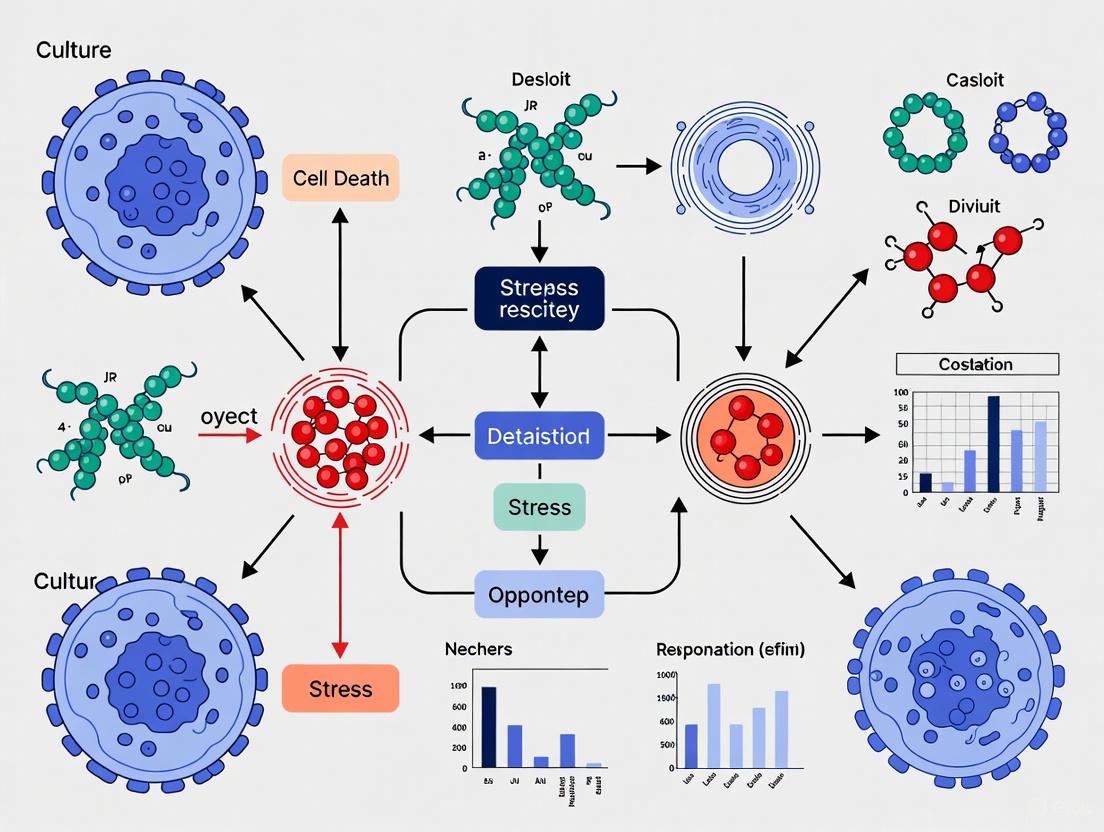

Core Signaling Pathways in Regulated Cell Death

The following diagrams illustrate the core molecular machinery of key RCD pathways, highlighting potential points of crosstalk.

Apoptosis Signaling Pathways

PANoptosis: An Integrated Cell Death Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential reagents and kits for studying RCD, a market projected to grow significantly in North America [6].

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Annexin V Assay Kits | Detects phosphatidylserine externalization on the outer leaflet of the cell membrane [3]. | Flow cytometric or microscopic identification of early apoptotic cells [6] [3]. |

| Caspase Activity Assays | Fluorogenic or luminescent measurement of caspase enzyme activity [3]. | Determining the specific initiator or executioner caspase involved in a death pathway [3]. |

| TUNEL Assay Kits | Labels fragmented DNA in late-stage apoptotic cells [3]. | Histological or flow cytometric detection of apoptosis in fixed cells or tissue sections [3]. |

| Anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 Antibodies | Detects the activated (cleaved) form of the key executioner caspase [3]. | Western blot or immunofluorescence confirmation of apoptotic commitment [3]. |

| Gasdermin D Antibodies | Detects full-length and cleaved (active) forms of GSDMD [2]. | Western blot confirmation of pyroptosis induction. |

| Phospho-MLKL Antibodies | Detects the phosphorylated, active form of MLKL [2] [4]. | Immunofluorescence or Western blot confirmation of necroptotic signaling. |

| Ferroptosis Inducers/Inhibitors | Compounds like Erastin (inducer) or Ferrostatin-1 (inhibitor) to modulate the pathway [2]. | Investigating the role of ferroptosis in a specific disease model or treatment context. |

Core Concepts: The Two Main Pathways to Apoptosis

What are the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of apoptosis?

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is triggered through two primary signaling cascades: the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Both pathways are crucial for development, tissue homeostasis, and immune function, and both culminate in the activation of caspases that execute cell death [8] [9].

- Extrinsic Pathway (Death Receptor Pathway): This pathway is initiated outside the cell when extracellular death ligands bind to cell surface death receptors. This binding leads to the formation of a Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC), which activates initiator caspase-8. Caspase-8 can then directly activate executioner caspases (like caspase-3) or amplify the death signal via the intrinsic pathway [8] [10].

- Intrinsic Pathway (Mitochondrial Pathway): This pathway begins from within the cell in response to severe internal stress, such as DNA damage, oxidative stress, or growth factor deprivation. These stresses trigger mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), leading to the release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors. Cytochrome c, together with Apaf-1, forms the apoptosome, which activates initiator caspase-9, subsequently activating executioner caspases [8] [9] [11].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these two pathways:

| Feature | Extrinsic Pathway | Intrinsic Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation | External death ligands (e.g., FasL, TNF-α) bind to death receptors [8] [11] | Internal cellular stress (e.g., DNA damage, hypoxia) [8] [9] |

| Key Initiator Caspase | Caspase-8 [8] [12] | Caspase-9 [8] [12] |

| Key Regulatory Proteins | Death Receptors (Fas, TNFR1), FADD, c-FLIP [8] | Bcl-2 family proteins (Bax, Bak, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL), p53 [8] [9] |

| Central Signaling Complex | Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) [8] [13] | Apoptosome [8] [11] |

| Mitochondrial Involvement | Can be involved via caspase-8 cleavage of Bid (crosstalk) [8] [10] | Central; defined by MOMP and cytochrome c release [8] [14] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My TUNEL assay is positive, but I do not detect other apoptotic markers. Is my cell death truly apoptotic?

A positive TUNEL assay alone is not conclusive evidence of apoptosis. While TUNEL detects DNA fragmentation, a hallmark of late apoptosis, this can also occur during necrotic cell death [9]. To confirm apoptosis, you should use a multi-parameter approach:

- Combine with Morphological Analysis: Apoptotic cells display characteristic morphology—cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and formation of small, round apoptotic bodies. Necrotic cells, in contrast, show cell and organelle swelling and membrane rupture [11].

- Measure Additional Apoptotic Markers:

- Caspase Activation: Detect cleaved, active forms of executioner caspases (e.g., caspase-3) via western blot or flow cytometry using activation-specific antibodies [9].

- Phosphatidylserine Exposure: Use Annexin V staining in combination with a viability dye (e.g., Propidium Iodide) to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) from late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) cells [9].

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm): Use dyes like TMRE to detect the loss of ΔΨm, an early event in the intrinsic pathway. Remember that this can also occur in necrosis and requires validation with other markers [9].

FAQ 2: I am not observing caspase activation in my cell death model, despite clear signs of cell demise. What could be happening?

The absence of caspase activation suggests your cells may be undergoing a form of non-apoptotic, programmed cell death. Caspase-independent death is a well-documented phenomenon [13] [12].

- Investigate Alternative Death Pathways:

- Necroptosis: This caspase-independent pathway can be activated by death receptors when caspase-8 is inhibited. Key markers include phosphorylation of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL [13] [12].

- Caspase-Indicated Apoptosis: The intrinsic pathway can sometimes release factors like Apoptosis-Inducing Factor (AIF) and Endonuclease G (EndoG), which can trigger chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation without caspase activity [8] [11].

- Experimental Validation:

- Use pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK) to see if cell death is suppressed. If death proceeds unabated, it is likely caspase-independent.

- Employ genetic models, such as cells deficient in key apoptotic components (e.g., Apaf-1⁻/⁻ or Bax⁻/⁻Bak⁻/⁻), where residual death often indicates alternative pathways [13].

FAQ 3: My background cell death is high in my optogenetic apoptosis induction system. How can I reduce it?

High background (light-independent) death is a common challenge in optogenetic systems like OptoBAX, where Cry2/CIB dimerization is used to activate BAX at the mitochondria [14].

- Utilize Improved Constructs: Newer generations of optogenetic switches have been engineered to reduce dark-state interactions. For example, using longer Cry2 variants (e.g., Cry2(1-531)) or incorporating point mutations (e.g., L348F) can significantly decrease background cytotoxicity while maintaining light-dependent efficacy [14].

- Optimize Expression Levels: High levels of pro-apoptotic component expression can lead to spontaneous activation. Titrate your transfection conditions to use the lowest effective concentration of your optogenetic construct.

- Verify Control Conditions: Always include cells expressing the optogenetic construct without light stimulation as a critical control to quantify and account for background death levels [14].

Essential Methodologies for Apoptosis Research

Protocol 1: Differentiating Apoptosis from Necroptosis using Genetic and Pharmacological Inhibitors

This protocol is essential for characterizing cell death pathways when caspase activity is absent [13] [12].

Materials:

- Pan-caspase inhibitor: Z-VAD-FMK

- Necroptosis inhibitor: Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1, targets RIPK1)

- Wild-type (WT) and relevant knockout cells (e.g., RIPK3 KO, Caspase-8 KO)

Method:

- Seed cells in culture plates and pre-treat for 1-2 hours with the following:

- DMSO (vehicle control)

- Z-VAD-FMK (e.g., 20 µM)

- Nec-1 (e.g., 10 µM)

- Z-VAD-FMK + Nec-1

- Apply your death-inducing stimulus.

- After an appropriate incubation period (e.g., 6-24 hours), quantify cell death using a method that distinguishes death mechanisms, such as:

- Flow Cytometry: Annexin V/PI staining to identify apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) and necroptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) populations.

- Viability Assay: Measure ATP levels or metabolic activity.

- Interpretation:

- Death suppressed by Z-VAD-FMK → Apoptosis.

- Death suppressed by Nec-1 but not Z-VAD-FMK → Necroptosis.

- In genetic models, increased cell survival in RIPK3/Caspase-8 DKO versus single knockouts indicates coordinated roles for both extrinsic apoptosis and necroptosis [13].

Protocol 2: Timelapse Imaging of Early Apoptotic Events using Fluorescent Reporters

This protocol leverages live-cell imaging to establish a kinetic timeline of early apoptosis following a defined trigger, such as optogenetic BAX activation [14].

Materials:

- Cells expressing your apoptosis inducer (e.g., OptoBAX 2.0 system) [14].

- Fluorescent reporters:

- Caspase activity sensor: e.g., a FRET-based reporter or a bright-to-dark GFP mutant containing a caspase-3 cleavage site (DEVD) [15].

- Actin dynamics: LifeAct-GFP or similar.

- Membrane integrity dye: Propidium Iodide (PI).

- Mitochondrial potential dye: TMRE.

Method:

- Plate cells expressing the inducer and relevant reporters in an imaging-appropriate dish.

- Place the dish on a live-cell imaging system with environmental control (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Acquire baseline images for all channels.

- Initiate apoptosis (e.g., deliver a pulse of blue light for OptoBAX).

- Continuously or intermittently acquire images over several hours.

- Analyze the sequence of events. A typical timeline in HEK293T cells after MOMP might be [14]:

- 0-30 min: Loss of TMRE fluorescence (ΔΨm collapse).

- ~1-2 hours: Caspase-3 reporter cleavage/activation.

- ~2 hours: Actin cytoskeleton redistribution and collapse.

- >2 hours: Plasma membrane permeabilization (PI uptake).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Apoptosis Research

The following table lists essential reagents for studying apoptosis, along with their primary applications.

| Research Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Annexin V Conjugates | Detects phosphatidylserine exposure on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, a marker of early apoptosis. Used in flow cytometry and microscopy [9]. |

| Caspase Activity Assays | Measure the activation of initiator and executioner caspases. Includes fluorogenic substrates, antibodies against cleaved caspases (e.g., cleaved caspase-3), and FRET-based live-cell reporters [9] [15]. |

| TUNEL Assay Kits | Labels the 3'-OH ends of fragmented DNA, identifying cells in late-stage apoptosis. Can be used for fluorescence microscopy, IHC, and flow cytometry [9]. |

| BCL-2 Family Antibodies | Detect expression and localization of pro- and anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins (e.g., Bax, Bak, Bim, Bcl-2). Critical for studying the intrinsic pathway [9] [10]. |

| Mitochondrial Dyes (e.g., TMRE, JC-1) | Assess mitochondrial health and function. The loss of fluorescence indicates a collapse in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), an early event in intrinsic apoptosis [9]. |

| Death Receptor Ligands (e.g., FasL, TRAIL) | Recombinant proteins used to specifically activate the extrinsic apoptosis pathway by engaging their cognate death receptors on the cell surface [8] [10]. |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | Tools to dissect death pathways. Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor), Necrostatin-1 (RIPK1 inhibitor for necroptosis), and BH3 mimetics (e.g., Venetoclax to inhibit Bcl-2) [9] [12]. |

| Optogenetic Systems (e.g., OptoBAX) | Allows precise, light-controlled initiation of apoptosis via specific pathways (e.g., mitochondrial membrane permeabilization), enabling high-resolution kinetic studies [14]. |

For researchers in cell culture and drug development, the classical view of cell death centered on apoptosis has significantly expanded. It is now clear that cells can undergo several other regulated cell death (RCD) pathways, including autophagy, necroptosis, and mitotic catastrophe, each with distinct morphological and biochemical characteristics [16] [17]. Understanding these pathways is crucial for interpreting experimental results, especially in cancer research where therapeutic agents often trigger multiple death mechanisms. This technical support center provides essential troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you accurately identify, distinguish, and investigate these complex cell death processes in your experimental models.

Defining the Pathways: Morphology and Key Biomarkers

Accurately identifying a specific cell death pathway requires correlating distinct morphological features with definitive biochemical biomarkers. The table below serves as a quick-reference guide for the essential characteristics of each process.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Non-Apoptotic Cell Death Pathways

| Cell Death Pathway | Morphological Features | Key Biomarkers | Primary Triggers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autophagy | Extensive cytoplasmic vacuolization, formation of double-membraned autophagosomes, no chromatin condensation early stages [16] [17] | LC3-I to LC3-II conversion, degradation of p62/SQSTM1, increased autophagic flux [18] | Nutrient deprivation, energy depletion, mTOR suppression, rapamycin [19] [17] |

| Necroptosis | Cellular & organellar swelling, plasma membrane rupture, no apoptotic body formation, no chromatin condensation [16] [17] | Phosphorylation of RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL; caspase-independent; inhibited by Necrostatin-1s [18] | Death receptor ligation, caspase inhibition (e.g., zVAD-fmk), TNF-α + BV6 + zVAD [18] |

| Mitotic Catastrophe | Formation of giant cells with multi- and/or micronucleation (>4N DNA content) [18] [20] [21] | Unscheduled activation of cyclin B1-CDK1, caspase-2 activation, mitotic arrest [19] | DNA-damaging agents (doxorubicin), anti-mitotic drugs (microtubule poisons like paclitaxel, colcemid) [22] [23] [21] |

Critical FAQ: The Status of Mitotic Catastrophe

Q: Is mitotic catastrophe a standalone form of regulated cell death?

A: No. According to the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death (NCCD), mitotic catastrophe is not classified as a separate form of RCD. Instead, it is an oncosuppressive mechanism that serves as a preliminary stage or process that precedes and primes cells for death via other pathways, such as apoptosis, necrosis, or senescence [16] [24]. It is a defensive process that senses mitotic failure and guides the cell toward an irreversible fate.

Pathway Interplay and Experimental Decision Points

A central challenge in cell death research is the extensive crosstalk between pathways. Your experimental conditions, such as genetic background or pharmacological inhibition, can determine the dominant death mechanism.

Key Crosstalk and Switching Mechanisms

- Mitotic Catastrophe as a Decision Platform: When mitotic catastrophe is induced, the cell's fate depends on its molecular profile. The balance between mitochondrial anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-xL, Mcl-1) can dictate whether the outcome is apoptosis or autophagy [22]. Furthermore, when apoptosis is suppressed (e.g., with the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk), cells with mitotic catastrophe hallmarks can switch to necroptosis [18].

- Autophagy's Dual Role: Autophagy can serve as a pro-survival mechanism, degrading damaged components and promoting recovery. However, it can also contribute to cell death. Inhibiting autophagy in cells undergoing mitotic catastrophe (e.g., with Bafilomycin A1 or ATG13 knockout) can upregulate RIP1 phosphorylation and promote a shift to necroptosis [18].

- The Apoptosis-Necroptosis Switch: The Ripoptosome complex (containing caspase-8, RIP1, and FADD) acts as a key switch. Active caspase-8 promotes apoptosis, but when its activity is inhibited, the balance shifts towards RIP1/RIP3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis [18].

The diagram below illustrates how mitotic catastrophe acts as a central hub, directing cell fate toward apoptosis, autophagy, or necroptosis based on specific experimental and cellular contexts.

Figure 1: Cell Fate Decisions Following Mitotic Catastrophe. Mitotic catastrophe serves as a pre-stage, with final death mode determined by specific inhibitors and protein expressions.

Troubleshooting Guides: Resolving Experimental Ambiguities

Guide 1: Differentiating Apoptosis from Necroptosis

Problem: Cell death is occurring, but classic apoptosis markers are negative, and the morphology appears necrotic.

Investigation Flow:

- Check Caspase Activity: If cleaved caspase-3/8 and PARP are not detected, apoptosis is unlikely.

- Test Inhibitors: Pre-treat cells with Necrostatin-1s (RIP1 inhibitor). If cell death is significantly suppressed, it indicates RIP1-dependent necroptosis.

- Confirm with Phospho-MLKL: Use immunofluorescence or Western blot to detect phosphorylated MLKL, the executioner of necroptosis [18].

- Control Experiment: Use a known necroptosis inducer (e.g., TNF-α + BV6 + zVAD-fmk) as a positive control for phospho-MLKL staining [18].

Guide 2: Determining the Role of Autophagy in Cell Death

Problem: It is unclear whether autophagy is contributing to cell death or acting as a pro-survival mechanism in your model.

Investigation Flow:

- Monitor Autophagic Flux: Do not rely on a single time point. Measure:

- LC3-II accumulation (Western blot) in the presence and absence of lysosomal inhibitors (Bafilomycin A1 or Chloroquine). An increase in LC3-II with inhibition indicates functional flux.

- p62/SQSTM1 degradation: A decrease in p62 levels suggests active autophagic degradation [18].

- Functional Inhibition: Use multiple approaches to inhibit autophagy:

- Assess Cell Viability: If inhibiting autophagy increases cell death, autophagy is likely pro-survival. If inhibiting autophagy decreases cell death, it is likely contributing to the death mechanism itself [18] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Cell Death Research

The following table lists key reagents used to study and modulate these cell death pathways, as cited in the literature.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Death Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| zVAD-fmk | Pan-caspase inhibitor | Used to inhibit apoptosis and unmask alternative death pathways like necroptosis following mitotic catastrophe [18]. |

| Necrostatin-1s | RIP1 kinase inhibitor | Specific inhibitor to confirm RIP1-dependent necroptosis; prevents phosphorylation of RIP1 and MLKL [18]. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor (blocks autophagy flux) | Inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion; used to measure autophagic flux and study autophagy's functional role [18] [20]. |

| 3-Methyladenine (3-MA) | Class III PI3K inhibitor (blocks autophagy initiation) | Inhibits early-stage autophagosome formation [20]. |

| Doxorubicin | DNA-damaging agent | Used at sub-lethal doses (e.g., 600 nM) to induce mitotic catastrophe in various carcinoma cell lines [22] [18]. |

| Colcemid | Microtubule polymerization inhibitor | Anti-mitotic agent used to arrest cells in metaphase and induce mitotic catastrophe [22]. |

| Podophyllotoxin (PPT) | Microtubule-targeting agent | Induces mitotic catastrophe and subsequent apoptosis in cancer cell models [21]. |

| Antibody: Phospho-MLKL | Detects active necroptosis executor | Key biomarker for confirming necroptosis via immunofluorescence or Western blot [18]. |

| Antibody: LC3B | Detects lipidated LC3 (LC3-II) | Standard marker for visualizing autophagosome formation and monitoring autophagy [18]. |

Advanced Considerations: Immunological Consequences

Beyond identifying the death mechanism, understanding its immunological impact is critical for cancer research. The mode of cell death can significantly influence anti-tumor immune responses.

- Mitotic Catastrophe and Immunogenicity: Cells undergoing mitotic catastrophe are characterized by multi/micronucleation. These micronuclei can activate the cGAS-STING pathway, a key sensor of cytosolic DNA that drives type I interferon production and enhances anti-tumor immunity [20]. This links chemotherapy-induced mitotic catastrophe to potentially improved responses to immunotherapy.

- Autophagy as an Immune Rheostat: Autophagy can degrade components of the anticancer immune response. For example, it can selectively degrade MHC-I molecules, thereby reducing antigen presentation and promoting immune evasion. Inhibiting autophagy in this context can enhance immune recognition of tumor cells [20].

The diagram below summarizes how a chemotherapeutic agent inducing mitotic catastrophe can lead to opposing outcomes on cancer immunity, regulated by autophagy.

Figure 2: Autophagy determines the immune outcome of mitotic catastrophe. While mitotic catastrophe can stimulate immunity via cGAS-STING, concomitant autophagy can dampen this response, suggesting a therapeutic benefit for autophagy inhibition in combination therapy.

FAQs: Cell Death Phenotypes in Research

Q1: What are the key morphological features that distinguish different types of regulated cell death?

A1: Different types of regulated cell death (RCD) exhibit distinct morphological characteristics under microscopy. The table below summarizes the hallmarks of major cell death types based on current classifications [25].

Table 1: Morphological Hallmarks of Major Cell Death Types

| Cell Death Type | Key Morphological Features |

|---|---|

| Apoptosis | Cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, chromatin condensation (pyknosis), nuclear fragmentation (karyorrhexis), formation of apoptotic bodies. |

| Autophagic Cell Death | Appearance of double-membrane autophagic vacuoles in the cytoplasm, degradation of cytoplasmic contents without immediate nuclear collapse. |

| Necroptosis | Cellular and organelle swelling (oncosis), plasma membrane rupture, release of intracellular contents, minimal chromatin condensation. |

| Pyroptosis | Cell swelling, formation of large pores in the plasma membrane, pro-inflammatory release of cytokines. |

| Ferroptosis | Shrunken mitochondria with increased membrane density, loss of mitochondrial cristae, but an absence of classic apoptotic or necrotic nuclear changes. |

Q2: Why might my Cell Painting assay fail to detect specific cell death phenotypes reliably?

A2: This is a common challenge. The timing of phenotype assessment is critical. A 2025 study indicates that shorter incubation periods (e.g., 6 hours for some cell lines) can better capture primary cellular alterations caused by a treatment, providing a more immediate and specific depiction of its action. Longer incubation times (e.g., 48 hours) can lead to an overwhelming of the assay by downstream secondary changes and disintegrated cells, masking the primary phenotype [26]. Furthermore, ensure your staining panel is optimized. For instance, an assay using dyes for actin, mitochondria, Golgi, ER, and nucleus provides compartment-specific information that is crucial for distinguishing death modalities [27].

Q3: How can I determine if a resistant phenotype in my cancer cell line is driven by genetic mutations or non-genetic plasticity?

A3 This requires a multi-faceted approach. The "genes-first" pathway is characterized by the acquisition of specific resistance mutations (e.g., BTK C481S mutations in CLL patients on ibrutinib). To investigate this, use DNA sequencing. In contrast, the "phenotypes-first" pathway involves non-heritable, dynamic transcriptional states and epigenetic reprogramming that allow cells to survive treatment without underlying genetic mutations. To probe this, employ single-cell RNA sequencing to reveal a continuum of transcriptional states, or use functional assays that test for drug sensitivity reversibility upon drug withdrawal [28].

Q4: My single-cell morphology data is inconsistent across experimental batches. How can I improve generalizability?

A4: Generalizability is a significant hurdle in single-cell phenotype prediction. Focus on robust, reproducible feature sets. One analysis found that nuclear AreaShape features (e.g., area, eccentricity, perimeter) were more resilient to dataset-specific biases than intensity-based features when models were applied to new data. Implement a rigorous leave-one-image-out (LOIO) cross-validation strategy to truly stress-test your model's performance on unseen data, as standard train-test splits can give a false sense of accuracy [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Weak or Non-Specific Signal in Optical Pooled Screening

Problem: You are conducting a genome-wide morphological screen (e.g., using PERISCOPE or a similar platform) but are getting weak phenotypic signals or cannot confidently assign phenotypes to genetic perturbations [27].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Optical Pooled Screening

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background noise in phenotypic images | Non-specific antibody binding or fluorescent dye precipitation. | - Titrate all antibodies and dyes.- Include blocking steps with serum from the secondary antibody host.- Filter sterile fluorescent dyes. |

| Poor correlation between optical and NGS barcode counts | Inefficient in situ sequencing (ISS) or barcode cross-talk. | - Optimize the TCEP destaining step to fully liberate fluorophores before ISS [27].- Validate that the Levenshtein distance between sgRNA barcodes is sufficient for error detection [27]. |

| Inability to detect compartment-specific phenotypes (e.g., mitochondrial defects) | Suboptimal staining or image analysis. | - Use a validated antibody for the compartment (e.g., anti-TOMM20 for mitochondria) [27].- Ensure your image analysis pipeline (e.g., in CellProfiler) is specifically tuned to extract features from the correct subcellular compartments. |

Issue: Differentiating Apoptosis from Other Death Mechanisms

Problem: Your viability assay indicates cell death, but you are unsure if it is apoptosis or another mechanism like ferroptosis or necroptosis.

Solution: Implement a multi-parameter assessment.

- Morphology: Use high-content imaging (as in Table 1) to look for classic features like membrane blebbing (apoptosis) vs. cell swelling (necroptosis) [25].

- Biochemical Probes: Use specific small-molecule inhibitors and activators.

- To rule in/out apoptosis: Use a pan-caspase inhibitor like Z-VAD-FMK. If death is inhibited, it is likely apoptosis.

- To rule in/out necroptosis: Use Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1), an inhibitor of RIPK1 [30].

- To rule in/out ferroptosis: Use Ferrostatin-1 or Liproxstatin-1, which inhibit lipid peroxidation. Conversely, compounds like erastin or RSL3 can be used as specific inducers to see if they replicate the phenotype [30].

- Pathway Analysis: Validate findings by checking for key biochemical events, such as the cleavage of caspase-3 (apoptosis) or the accumulation of lipid peroxides (ferroptosis) [25] [30].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Cell Painting for Cell Death Morphology Profiling

This protocol is adapted from the PERISCOPE pipeline for generating high-dimensional morphological profiles [27].

Principle: Simultaneously label multiple organelles to create a comprehensive morphological fingerprint of the cell, which can be used to classify different death phenotypes.

Reagents:

- Fixative: 4% Formaldehyde in PBS.

- Permeabilization Solution: 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS.

- Blocking Solution: 1-3% BSA in PBS.

- Staining Panel (destainable, via disulfide linkers recommended):

- Actin: Phalloidin conjugated to a fluorophore (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488).

- Mitochondria: Anti-TOMM20 antibody, followed by a fluorescent secondary.

- Golgi and Plasma Membrane: Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) conjugated to a fluorophore.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum: Concanavalin A (ConA) conjugated to a fluorophore.

- Nucleus: 4',6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DAPI).

- Destaining Solution: Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP).

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Perturbation: Seed cells in an appropriate multi-well plate (e.g., 96-well). Treat with compounds or perform genetic perturbations to induce cell death.

- Fixation: Aspirate media and add 4% formaldehyde for 15-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization and Blocking: Wash with PBS, then permeabilize and block with blocking solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30-60 minutes.

- Staining: Incubate with the pre-mixed staining panel in blocking solution for 1-2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Protect from light.

- Imaging: Acquire high-content images using a fluorescent microscope with the appropriate filter sets for each dye.

- Destaining (if performing subsequent ISS): Treat cells with TCEP to cleave the disulfide-linked fluorophores and remove the phenotypic stain [27].

- Image Analysis: Use open-source software like CellProfiler to segment cells and identify subcellular compartments. Then, use Pycytominer to process and normalize the extracted single-cell features for downstream analysis [27] [29].

Protocol: Chemical Biology Screening for Non-Apoptotic Cell Death

This protocol outlines the use of specific chemical tools to discover and characterize non-apoptotic cell death pathways like ferroptosis [30].

Principle: Use selective small-molecule inducers and inhibitors to trigger and probe a specific cell death pathway in an agnostic phenotypic screen.

Reagents:

- Inducers:

- Erastin: Inhibits system xc-, depleting glutathione.

- RSL3, ML162, ML210: Direct inhibitors of GPX4.

- Inhibitors:

- Ferrostatin-1, Liproxstatin-1: Potent inhibitors of ferroptosis that scavenge lipid radicals.

- Deferoxamine (DFO): An iron chelator.

Procedure:

- Phenotypic Screening: Seed cells in 384-well plates. Treat with a library of small molecules alongside known inducers (e.g., Erastin) and controls.

- Viability Readout: After 24-72 hours, measure cell viability using a metabolism-based assay (e.g., ATP content). Crucially, do not use an assay specific only for apoptosis.

- Hit Validation: Re-test hits for dose-dependent lethality.

- Mechanism Elucidation:

- Specificity Test: Co-treat hit compounds with Ferrostatin-1 or Liproxstatin-1. If cell death is rescued, the compound likely induces ferroptosis.

- Biochemical Confirmation: Measure downstream events like glutathione depletion, lipid peroxidation (e.g., with BODIPY 581/591 C11 probe), or GPX4 activity.

- Target Identification: Use techniques like chemoproteomics or chemical genetic analysis to identify the molecular target of the hit compound [30].

Signaling Pathway & Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Core Apoptotic Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Core Apoptotic Signaling Pathways.

PERISCOPE Screening Workflow

Diagram 2: Genome-Wide Morphology Screening Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cell Death Morphology Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Application in Cell Death Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Libraries (e.g., CROP-seq vector) | Targeted gene knockout at scale. | Enables genome-wide screening for genes whose knockout alters cell morphology or induces specific death phenotypes [27]. |

| Cell Painting Panel (Phalloidin, TOMM20, WGA, ConA, DAPI) | Multiplexed staining of actin, mitochondria, Golgi/ membrane, ER, and nucleus. | Generates high-dimensional morphological profiles to classify and distinguish different cell death mechanisms [27] [26]. |

| Chemical Biology Probes (e.g., Erastin, RSL3, Nec-1, Fer-1) | Specific inducers and inhibitors of non-apoptotic death pathways (e.g., ferroptosis, necroptosis). | Used as tool compounds to trigger or inhibit specific death pathways for phenotypic characterization and target validation [30]. |

| CellProfiler | Open-source software for image analysis and feature extraction. | Segments cells and quantifies thousands of morphological features from microscopy images for objective phenotype classification [27] [29]. |

| Pycytominer | Data processing package for morphological profiles. | Normalizes, aggregates, and annotates single-cell data from CellProfiler, preparing it for downstream machine learning analysis [27] [29]. |

Scientific Foundations of Cell Death in Culture

In cell culture research, cell death is not merely an endpoint but a critical, dynamic process that must be carefully monitored and managed. Understanding the different forms of cell death is essential for interpreting experimental results and maintaining the integrity of your research models.

Forms of Cell Death in Experimental Systems

Cell death in culture can be broadly categorized into several distinct forms, each with unique morphological and biochemical characteristics:

Apoptosis: A highly regulated, programmed cell death process characterized by cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and formation of apoptotic bodies. It is typically non-inflammatory and crucial for eliminating damaged or unnecessary cells. Key executors are caspases, which are activated through either the extrinsic (death receptor) or intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways [31] [32].

Necroptosis: A form of programmed necrosis that is inflammatory in nature. It depends on receptor-interacting protein kinases (RIPK1 and RIPK3) and culminates in plasma membrane rupture [33] [34].

Pyroptosis: An inflammatory lytic cell death mediated by gasdermin proteins, which form pores in the plasma membrane. It often occurs in response to pathogenic infections and involves inflammasome activation [33] [34].

Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of cell death driven by excessive lipid peroxidation of cell membranes. It is characterized by mitochondrial shrinkage and is regulated by cellular redox balance and iron metabolism [33] [34] [35].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these cell death pathways:

| Cell Death Type | Key Regulators/Mediators | Morphological Features | Inflammatory Response | Primary Triggers in Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | Caspases, BCL-2 family, Cytochrome c [31] | Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, apoptotic bodies [31] | No | Serum withdrawal, UV irradiation, DNA damage [31] |

| Necroptosis | RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL [33] | Cellular swelling, plasma membrane rupture | Yes | TNFα signaling, caspase inhibition [33] |

| Pyroptosis | Gasdermins, Inflammasomes, Caspase-1/4/5 [34] | Pore formation, cell lysis, IL-1β release | Yes | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [34] |

| Ferroptosis | Lipid peroxides, Iron, GPX4, FSP1 [33] [35] | Mitochondrial shrinkage, loss of cristae | Variable | Glutathione depletion, GPX4 inhibition, FSP1 inhibition [35] |

The Homeostatic Imperative in Culture Systems

In a healthy organism, approximately one million cells die every second to maintain tissue homeostasis [33]. This delicate balance is replicated in vitro, where the equilibrium between cell proliferation, adaptation, and death determines the health of your culture. Disruption of this balance—through excessive or insufficient cell death—leads to experimental artifacts and unreliable data [33] [31].

Excessive cell death in culture can manifest in inflammatory and degenerative phenotypes, mirroring pathologies such as neurodegenerative diseases. Conversely, insufficient cell death, often resulting from the silencing of pro-death genes or activation of survival pathways, creates models of cancer where cells evade normal turnover mechanisms [33].

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My cultured cells are dying rapidly after passaging. What could be the cause? Rapid cell death post-passaging often results from enzymatic over-digestion during detachment. Over-exposure to trypsin/EDTA degrades cell surface proteins and activates cell death pathways [36] [37]. Solution: Optimize dissociation time and consider milder enzyme mixtures like Accutase for sensitive cells [38]. Always neutralize enzymatic activity promptly with serum-containing medium.

Q2: How can I determine if cell death in my experiment is apoptotic versus necrotic? Use multiparameter assessment combining morphology and specific markers:

- Apoptosis: Look for cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and caspase activation (detectable with fluorogenic substrates). Annexin V staining (for phosphatidylserine exposure) combined with a viability dye is a standard assay [31].

- Necrosis/Necroptosis: Characterized by cellular swelling and plasma membrane rupture. Measure release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the culture medium. Specific necroptosis can be inhibited by necrostatin-1 (RIPK1 inhibitor) [31].

Q3: My cancer cell lines are not responding to pro-apoptotic stimuli. How can I overcome this? Many cancer cells develop resistance to apoptosis by upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins like BCL-2 [31]. Strategy: Consider inducing alternative death pathways. Research shows that triggering ferroptosis using FSP1 inhibitors can effectively eliminate apoptosis-resistant melanoma and lung cancer cells in vivo [35]. This approach exploits the specific metabolic dependencies of cancer cells.

Q4: What are the consequences of using high-passage cell lines? High-passage cell lines undergo phenotypic and genotypic changes (genetic drift), which can alter their response to stimuli. For example, transfection efficiency may increase or decrease, and sensitivity to cell death inducers can shift dramatically [36]. Best Practice: Authenticate cell lines regularly and use low-passage stocks for critical experiments. Maintain detailed records of population doubling levels (PDLs) rather than just passage numbers [36].

Q5: How does serum starvation induce cell death and is it a good model? Serum withdrawal primarily activates the intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptosis pathway due to deprivation of survival signals. While a common model for stress-induced apoptosis, be aware that the response is cell-type specific and may not fully replicate in vivo death contexts [31].

Advanced Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Cell Death Pathway Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected cell clustering and death in suspension | Release of DNA from dead cells increases medium viscosity; Cell stress [37] | Add low concentrations of DNase I to the medium; Optimize seeding density and agitation | Apoptosis, Secondary Necrosis |

| Poor attachment and anoikis | Inappropriate surface coating; Lack of essential survival signals [38] | Pre-coat with ECM proteins (e.g., collagen, fibronectin); Use conditioned medium or Rho-kinase (ROCK) inhibitor for sensitive cells | Anoikis (a form of apoptosis) |

| Failure to induce ferroptosis despite using known inducers | Redundant antioxidant systems (e.g., FSP1, GSH); Inadequate iron availability [35] | Combine GPX4 inhibition with FSP1 inhibitors; Ensure medium contains transferrin or other iron sources | Ferroptosis |

| Inconsistent death responses in 3D vs 2D culture | Poor penetrance of inducers; Differential microenvironments [38] | Optimize inducer concentration and exposure time; Validate death markers specific to 3D context (e.g., core vs. periphery) | Varies (often Apoptosis) |

| Cell line contamination with mycoplasma | Alters metabolism and sensitizes cells to death; masks genuine experimental effects [38] [37] | Implement routine mycoplasma testing using PCR-based kits; quarantine new cell lines; use antibiotics specifically effective against mycoplasma | Variable (often increases baseline apoptosis) |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Apoptosis via Annexin V/Propidium Iodide Staining

Principle: This flow cytometry-based assay distinguishes live cells (Annexin V-/PI-), early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic cells (Annexin V-/PI+).

Procedure:

- Harvest cells: Gently collect adherent cells using non-enzymatic dissociation buffer to prevent degradation of phosphatidylserine [38].

- Wash: Pellet cells (300 x g for 5 min) and resuspend in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Stain: Resuspend 1x10^5 cells in 100 μL of binding buffer containing Annexin V-fluorochrome conjugate (as per manufacturer's recommendation) and incubate for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature.

- Add PI: Add propidium iodide (final concentration 1 μg/mL) to the cell suspension immediately before analysis.

- Analyze: Acquire data on a flow cytometer within 1 hour. Use unstained and single-color controls for compensation [31].

Protocol: Inducing and Validating Ferroptosis

Principle: Ferroptosis is triggered by glutathione depletion or direct GPX4 inhibition, leading to accumulation of lipid peroxides.

Procedure:

- Induction:

- Validation:

- Viability Assay: Measure cell viability using a resazurin-based assay.

- Lipid Peroxidation: Detect using C11-BODIPY 581/591 fluorescent probe (5 μM, 30 min incubation) by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

- Inhibition Test: Confirm ferroptosis specificity by co-treating with 100 nM Ferrostatin-1 (lipophilic antioxidant) or 1 μM Liproxstatin-1 [35].

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram Title: TNF Signaling to Apoptosis or Necroptosis

Diagram Title: Core Ferroptosis Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin/EDTA [39] [36] | Proteolytic enzyme mixture for dissociating adherent cells. | Routine passaging of adherent cell lines. |

| Milder Dissociation Agents (Accutase, Accumax) [38] | Enzyme blends less damaging to surface proteins than trypsin. | Passaging sensitive cells; when surface protein integrity is crucial for downstream assays. |

| Annexin V Conjugates [31] | Binds to phosphatidylserine exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. | Flow cytometric detection of early apoptosis. |

| Caspase Inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK) [31] | Broad-spectrum, cell-permeable irreversible caspase inhibitor. | To confirm caspase-dependent apoptosis or to shift death to necroptosis. |

| Ferroptosis Inhibitors (Ferrostatin-1, Liproxstatin-1) [35] | Potent, specific inhibitors of ferroptosis that reduce lipid peroxidation. | To confirm ferroptotic cell death in experimental settings. |

| FSP1 Inhibitors [35] | Small molecules targeting the ferroptosis suppressor protein 1. | To induce ferroptosis in cancer models, especially those resistant to apoptosis. |

| Gasdermin Inhibitors | Compounds that inhibit gasdermin pore formation. | To specifically inhibit pyroptosis in models of infection or inflammation. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Inhibits Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase. | Reduces anoikis in primary cells and stem cells after passaging. |

Detecting Cell Death: A Guide to Biomarkers and Analytical Techniques

FAQs: Biomarkers for Cell Death Detection and Troubleshooting

1. What are the key differences between biomarkers for apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy?

Biomarkers detect distinct morphological and biochemical events in each cell death pathway. The table below summarizes the primary biomarkers used to differentiate these processes.

Table 1: Key Biomarkers for Major Cell Death Pathways

| Cell Death Pathway | Key Biomarkers | Detection Methods | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | Activated caspases (e.g., Caspase-3), caspase-cleaved substrates (e.g., CK18), phosphatidylserine externalization, DNA fragmentation [40] [41] | TUNEL assay, Annexin V staining, ELISA (M30), IHC for cleaved caspases [40] | Caspase-dependent, regulated process, no inflammatory response [40] |

| Necrosis/Necroptosis | Release of intracellular contents (e.g., HMGB1), plasma membrane rupture, RIP1/RIP3 kinase activation [41] | Trypan blue uptake, LDH release assay [42] | Accidental or regulated, inflammatory, loss of membrane integrity [42] |

| Autophagy | LC3-I to LC3-II conversion, autophagosome formation, p62 degradation [41] | Western blot (LC3-II/p62), fluorescence microscopy (GFP-LC3) [41] | Formation of double-membrane vesicles, role in cell survival and death [41] |

2. My cell culture is showing high mortality. How can I determine if apoptosis is the primary cause and which biomarker should I use?

First, perform careful microscopic examination for classic morphological features of apoptosis, such as cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and the presence of cell "ghosts" or debris [42]. For confirmation, follow these steps:

- Initial, Accessible Assay: Use a trypan blue exclusion assay to quickly assess the percentage of cells with compromised plasma membranes, a late feature of apoptosis [42].

- Specific Apoptosis Detection: To specifically confirm apoptosis, use an Annexin V staining assay, which detects the externalization of phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, an early apoptotic event. This is often used in conjunction with propidium iodide (PI) to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) from late apoptotic or necrotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+) [40].

- For High-Specificity and Quantification: Implement an ELISA-based assay such as the M30 Apoptosense ELISA, which detects a caspase-cleaved neo-epitope of cytokeratin 18 (CK18). This provides a highly specific, quantitative measure of epithelial cell apoptosis in plasma or culture supernatant and can be correlated with tumor burden or treatment response [43].

3. The M30 and M65 ELISAs both measure cytokeratin-18. What is the difference, and when should I use each?

The M30 and M65 assays detect different forms of Cytokeratin-18 (CK18) and provide complementary information on the type and extent of cell death.

- M65 Assay: Measures both intact and caspase-cleaved CK18. It is a biomarker of overall epithelial cell death, capturing death through both caspase-dependent (apoptosis) and caspase-independent pathways [43].

- M30 Assay: Detects only a specific neo-epitope on CK18 exposed after caspase cleavage at amino acids 387-396. It is considered a specific biomarker for epithelial apoptosis [43].

You should use these assays in tandem to gain a deeper understanding of your cell death mechanism. A high M30 value indicates significant apoptosis, while a high M65 value with a low M30 value suggests cell death is occurring primarily through non-apoptotic pathways (e.g., necrosis) [43].

4. What are the most promising emerging biomarkers in cell death research?

The field is rapidly moving beyond traditional markers towards highly sensitive, non-invasive biomarkers that can provide real-time insights.

- Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA): Fragments of DNA released by tumor cells into the bloodstream. It shows great promise for early cancer detection and monitoring treatment response through liquid biopsies [44].

- Non-Coding RNAs (ncRNAs): This class includes:

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): Small RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. Aberrant miRNA expression is linked to tumor progression and treatment response [45].

- Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and Circular RNAs (circRNAs): These can act as "molecular sponges" for miRNAs or interact with proteins to modulate key signaling pathways like apoptosis [40] [45].

- Exosomes: Small extracellular vesicles that carry proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (including ncRNAs). They are emerging as crucial mediators of intercellular communication in the tumor microenvironment and are a rich source of biomarkers [44].

5. How can machine learning (ML) aid in biomarker discovery for complex diseases like cancer and atherosclerosis?

Machine learning is transformative for analyzing high-dimensional data from omics technologies (e.g., metabolomics, transcriptomics). Key applications include:

- Handling Complex Data: ML algorithms can identify subtle patterns in large, complex datasets where traditional statistics fail, integrating clinical and molecular data for a holistic view [46].

- Feature Selection: ML methods like LASSO regression, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machines (SVM) can identify the most predictive features from thousands of candidates, refining biomarker panels for accuracy and clinical utility [46] [47].

- Improved Diagnostic Models: Studies have demonstrated that ML models can integrate clinical risk factors (e.g., smoking, BMI) with metabolite profiles to predict diseases like large-artery atherosclerosis with high accuracy (AUC > 0.90) [46].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting Epithelial Cell Death via M30 and M65 ELISAs

This protocol is adapted from research evaluating circulating CK18 as a biomarker of drug-induced apoptosis [43].

1. Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect blood samples in heparin-coated tubes.

- Centrifuge samples at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C to isolate plasma.

- Aliquot plasma and store immediately at -70°C until analysis.

2. M30 and M65 ELISA Procedure:

- Add 25 µL of each standard, control, or plasma sample to the pre-coated 96-well plate.

- Add 75 µL of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated detection antibody to each well.

- Add 4 µL of a heterophilic antibody blocking reagent (e.g., HBR) to prevent false-positive signals.

- Incubate the plate at room temperature for 2 hours (M65 assay) or 4 hours (M30 assay).

- Wash the plate to remove unbound conjugate.

- Add 200 µL of TMB substrate and incubate for 20 minutes in the dark.

- Stop the reaction by adding 50 µL of 1.0 M sulphuric acid.

- Read the absorbance at 540 nm. Calculate the concentration of antigen (U/L) based on the standard curve. Values below 20 U/L are typically considered at the limit of detection.

Protocol 2: Profiling Non-Coding RNA Expression via RNA Sequencing

This outline describes a standard workflow for investigating ncRNAs as biomarkers [45].

1. RNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Extract total RNA from cells, tissue, or biofluids (e.g., plasma) using a method that preserves small RNAs.

- Assess RNA integrity and concentration using an instrument like a Bioanalyzer.

2. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- For miRNA sequencing, use a protocol that includes size selection to enrich for small RNAs.

- For lncRNA and circRNA analysis, use ribosomal RNA depletion to remove abundant ribosomal RNAs.

- Prepare sequencing libraries and perform high-throughput sequencing on a platform such as Illumina.

3. Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align sequencing reads to the reference genome.

- Use specialized tools to quantify expression levels of known miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs, and to discover novel transcripts.

- Perform differential expression analysis to identify ncRNAs associated with your experimental condition (e.g., treated vs. control).

- Conduct pathway analysis to predict the biological functions and pathways regulated by the differentially expressed ncRNAs.

Key Signaling Pathways

The Intrinsic Apoptosis Pathway and Regulatory Networks

This diagram illustrates the core intrinsic apoptosis pathway and its regulation by Bcl-2 family proteins and non-coding RNAs, a key mechanism often investigated in cell death research.

Experimental Workflow for Biomarker Discovery and Validation

This diagram outlines a modern, integrated workflow for discovering and validating novel cell death biomarkers, incorporating machine learning and multi-modal data.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Cell Death Biomarker Research

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| M30 Apoptosense ELISA | Quantifies caspase-cleaved CK18 (Asp396) | Specific detection of epithelial apoptosis in plasma/supernatant [43] |

| M65 ELISA | Quantifies total CK18 (intact and cleaved) | Measuring overall epithelial cell death [43] |

| Annexin V Staining Kits | Detects phosphatidylserine externalization | Flow cytometry or microscopy to identify early apoptotic cells [40] |

| Absolute IDQ p180 Kit | Targeted metabolomics profiling | Quantifying 194 metabolites from 5 classes for biomarker discovery [46] |

| LC3 Antibody | Detects LC3-I to LC3-II conversion | Western blot or immunofluorescence to monitor autophagy [41] |

| TUNEL Assay Kits | Labels DNA strand breaks | Detecting late-stage apoptosis in fixed cells or tissues [40] |

| Heterophilic Antibody Blocking Reagent (HBR) | Blocks interfering antibodies | Improving specificity in immunoassays like M30/M65 ELISA [43] |

Within the critical field of cell death research, accurately distinguishing between different mechanisms of death, such as apoptosis and necrosis, is paramount. Flow cytometry serves as a powerful tool for this purpose, allowing researchers to quantitatively analyze key biochemical events including DNA fragmentation and loss of membrane integrity. However, the accuracy of this data is highly dependent on optimized protocols and careful troubleshooting. This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges and provides detailed methodologies to ensure the reliability of your flow cytometry data in cell death studies.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal for DNA Stain | - Incorrect flow rate [48]- Insufficient staining [48]- Inadequate fixation/permeabilization [48] | - Use the lowest flow rate setting [48]- Ensure sufficient incubation time with DNA dye (e.g., PI/RNase for ≥10 min) [48]- Confirm fixation/permeabilization protocol is appropriate for DNA staining (e.g., ice-cold methanol) [48] |

| High Background in Membrane Integrity Staining | - Presence of dead cells [48] [49]- Non-specific antibody binding [48] [49]- Insufficient washing [48] | - Use a viability dye to gate out dead cells during live cell surface staining [48]- Block cells with BSA or Fc receptor blocking reagents prior to staining [48] [49]- Increase the number of washes after antibody incubation steps [48] [49] |

| Poor Resolution of Cell Cycle Phases | - High flow rate [48]- Insufficient cell number or dye concentration [50]- Presence of cellular aggregates [50] | - Run samples at the lowest flow rate setting [48]- Optimize cell number and dye concentration; ensure incubation time and temperature are correct [50]- Use doublet discrimination gates in analysis to exclude aggregates [50] |

| Abnormal Scatter Profile | - Clogged flow cell [48]- Cell sample is lysed or contains debris [49]- Bacterial contamination [50] | - Unclog the instrument per manufacturer's instructions (e.g., run 10% bleach followed by dH₂O) [48]- Ensure gentle sample preparation; avoid high-speed centrifugation/vortexing; filter cells to remove debris [49]- Check sample for contamination [50] |

| Excessive Fluorescence Signal | - Antibody concentration too high [49]- Insufficient blocking [49]- Fluorophore too bright for antigen density [49] | - Titrate the antibody to find the optimal concentration [49]- Increase concentration of blocking agent and/or blocking incubation time [49]- Pair a dim fluorochrome (e.g., FITC) with a high-density target [48] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Experimental Setup

Q1: What are the essential controls for a flow cytometry experiment analyzing cell death? For reliable data, include the following controls:

- Unstained cells: To assess cellular autofluorescence [48].

- Untreated/Unstimulated cells: To establish a baseline signal.

- Single-stained controls: Critical for compensation when using multiple fluorochromes [50].

- Viability dye control: To properly gate out dead cells and reduce background [48].

- FMO (Fluorescence Minus One) controls: For accurate gating when setting up multicolor panels, as they help distinguish positive from negative populations better than unstained cells alone [50].

Q2: My antibody works in other applications (e.g., immunofluorescence) but not in flow cytometry. What could be wrong? An antibody's performance is application-specific. First, check the manufacturer's data sheet to confirm it is validated for flow cytometry [48]. If it is only approved for immunofluorescence, you may need to perform a titration series to determine the optimal concentration for flow [48]. The experimental conditions, including fixation and permeabilization, can significantly impact antibody binding and require optimization.

Sample Preparation and Staining

Q3: How should I prepare adherent cells for Annexin V staining to avoid artifactual results? Treating adherent cells with trypsin or other detachment reagents can damage the cell membrane and cause false-positive Annexin V staining. After detachment, allow your cells to recover for 30-45 minutes in culture medium in the incubator, gently swirling periodically to prevent re-attachment. After this recovery period, you can proceed with Annexin V labeling and analysis [50].

Q4: Why is it critical to differentiate between assays for "viability," "cell death," and "apoptosis"? These terms represent distinct biological claims and require different experimental evidence [51].

- Viability is a broad term for the number of living cells, often measured by metabolic activity (e.g., MTT, resazurin assays) or total protein content.

- Cell Death specifically requires evidence of dying cells, measured by assays for death-related alterations like loss of membrane integrity (e.g., PI uptake, LDH release).

- Apoptosis is a specific, programmed form of cell death that requires evidence of its characteristic features, such as phosphatidylserine externalization (Annexin V), caspase activation, or DNA fragmentation (TUNEL assay).

Using a single assay, like a tetrazolium reduction test, to support multiple distinct claims is a common misinterpretation that can lead to incorrect conclusions [51].

Instrumentation and Analysis

Q5: I am detecting a very high event rate. What should I check? A high event rate can be caused by several factors [50]:

- An air bubble in the flow cell.

- A sample threshold set too low.

- The photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltage for the threshold parameter being set too high.

- A sample that is too concentrated.

- Bacterial contamination in the sample. Systematically check these parameters, starting with sample concentration and instrument threshold settings.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analyzing DNA Fragmentation for Apoptosis

Principle: This protocol detects the internucleosomal cleavage of DNA, a hallmark of apoptosis, by using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. The enzyme TdT incorporates fluorescently-labeled dUTP at the free 3'-OH ends of fragmented DNA, which can be quantified by flow cytometry.

Reagents:

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% methanol-free formaldehyde [48])

- Permeabilization Buffer (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100 in citrate buffer or ice-cold 70% ethanol [48])

- TUNEL Assay Kit (containing TdT enzyme and fluorescent-dUTP)

- Propidium Iodide/RNase Staining Buffer (optional for cell cycle correlation)

Procedure:

- Prepare Single-Cell Suspension: Harvest and wash cells in PBS. Adjust concentration to 1-5 x 10^6 cells/mL.

- Fix Cells: Fix cells in 4% formaldehyde for 15-30 minutes at room temperature. Critical: Use methanol-free formaldehyde to prevent loss of intracellular proteins and preserve TUNEL reactivity [48].

- Permeabilize Cells: Pellet cells and permeabilize with ice-cold 70% ethanol or 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15-30 minutes on ice. Note: For ethanol permeabilization, chill cells on ice first and add ethanol drop-wise while vortexing to prevent hypotonic shock [48].

- Wash: Wash cells twice with PBS to remove residual fixative and permeabilization buffer.

- Label DNA Strand Breaks: Resuspend the cell pellet in the TUNEL reaction mixture according to the manufacturer's instructions. Incubate for 60 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Wash and Analyze: Wash cells twice with PBS and resuspend in PBS for flow cytometry analysis. If performing dual staining, resuspend in PI/RNase solution and incubate for at least 10 minutes before analysis [48].

- Flow Cytometry: Acquire data using a low flow rate to improve resolution and reduce coefficient of variation (CV) [48].

Protocol 2: Assessing Plasma Membrane Integrity

Principle: This protocol distinguishes between intact and compromised plasma membranes, a key differentiator between early apoptotic (intact membrane) and necrotic (compromised membrane) cells. It utilizes Annexin V, which binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) exposed on the outer leaflet of the membrane in apoptotic cells, and a viability dye like Propidium Iodide (PI) that is excluded by live cells but enters dead cells.

Reagents:

- Annexin V Binding Buffer

- Fluorescently-conjugated Annexin V

- Viability Stain (e.g., Propidium Iodide (PI) or 7-AAD)

- PBS

Procedure:

- Harvest Cells Gently: For adherent cells, use gentle enzymatic (e.g., non-trypsin) or mechanical dissociation to avoid artifactual membrane damage. Allow cells to recover post-detachment for 30-45 minutes [50].

- Wash: Wash cells once with cold PBS.

- Resuspend in Binding Buffer: Resuspend cell pellet (approximately 10^5 - 10^6 cells) in Annexin V Binding Buffer.

- Stain: Add fluorescently-conjugated Annexin V and viability dye (PI/7-AAD) to the cell suspension. Incubate for 15-20 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Analyze: Without washing, analyze the cells by flow cytometry within 1 hour. Note: Since Annexin V binding is calcium-dependent, the binding buffer must contain Ca²⁺.

Data Interpretation:

- Annexin V-/ PI-: Viable, healthy cells.

- Annexin V+/ PI-: Early apoptotic cells (PS externalized, membrane intact).

- Annexin V+/ PI+: Late apoptotic or necrotic cells (membrane integrity lost).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Cell Death Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Stains | Propidium Iodide (PI) [48], DAPI [48], DRAQ5 [48] | DNA intercalating dyes used for cell cycle analysis and, when combined with RNase, to distinguish apoptotic sub-G1 peaks. PI is also used as a viability dye to assess membrane integrity. |

| Viability Dyes | 7-AAD [48], Fixable Viability Dyes (e.g., eFluor) [48], LIVE/DEAD Fixable Stains [50] | Used to identify and gate out dead cells from analysis, which is crucial as dead cells can bind antibodies non-specifically and increase background [48]. |

| Apoptosis Markers | Annexin V conjugates [50], Caspase Activity Assays, TUNEL Assay Kits | Annexin V binds to externalized phosphatidylserine, an early marker of apoptosis. Caspase assays detect enzyme activity, and TUNEL kits label fragmented DNA. |

| Fixation & Permeabilization Reagents | Formaldehyde (4%, methanol-free) [48], Methanol (90%, ice-cold) [48], Triton X-100 [48], Saponin [48] | Fixation stabilizes cells and prevents degradation. Permeabilization allows intracellular access for antibodies or DNA dyes. The choice depends on the target antigen and application. |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [48], Normal Serum [48], Fc Receptor Blocking Reagents [48] [49] | Reduce non-specific antibody binding by blocking reactive sites on cells and Fc receptors, thereby lowering background signal. |

Core Principles and Application to Cell Death Research

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a powerful plate-based technique widely used for detecting and quantifying peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones within complex biological samples. [52] [53] Its principle relies on immobilizing a target antigen to a solid surface, complexing it with a specific antibody linked to an enzyme, and then measuring the conjugated enzyme's activity via incubation with a substrate to produce a quantifiable product. [52] [53] In the context of cell death research, such as apoptosis, ELISA provides a reliable method to quantify specific circulating biomarkers like activated caspases or other released intracellular proteins. For instance, apoptosis can be monitored by detecting mono- and oligonucleosomes released into the cell culture media using a specialized Cell Death Detection ELISA. [54]

ELISA Formats and Their Utility in Biomarker Detection

Several ELISA formats can be employed based on the research goal, each with distinct advantages for detecting cell death biomarkers:

- Sandwich ELISA: This method is highly specific and ideal for quantifying biomarkers like cytokines or activated caspases in complex samples such as cell culture supernatants or patient serum. It uses two antibodies specific to different epitopes on the target antigen, enhancing specificity and sensitivity without requiring sample purification. [52]

- Competitive ELISA: Often used to measure small molecules or antibodies, this format is based on the competition between a sample antigen and an enzyme-labeled antigen for a limited number of antibody-binding sites. [52] [53]

- Direct ELISA: A simpler, faster format where the antigen is directly immobilized and detected by an enzyme-labeled primary antibody. [52]

- Indirect ELISA: Similar to direct ELISA but uses an unlabeled primary antibody followed by an enzyme-labeled secondary antibody, offering signal amplification. [52]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common ELISA Challenges and Solutions

Researchers often encounter specific issues during ELISA experiments. The following tables outline common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Signal and Background Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal [55] [56] | Reagents not at room temperature | Allow all reagents to sit for 15-20 minutes before starting the assay. [55] |

| Incorrect reagent storage or expired reagents | Double-check storage conditions (typically 2-8°C) and confirm all reagents are within their expiration dates. [55] | |

| Insufficient or improper antibody binding | Ensure you are using an ELISA plate (not a tissue culture plate) and confirm correct antibody concentrations and incubation times. [55] [56] | |

| Plate read at incorrect wavelength | Verify the recommended wavelength for the substrate being used (commonly 450 nm) and set the plate reader accurately. [55] | |

| Wells scratched during pipetting or washing | Use caution when dispensing and aspirating; calibrate automated washers so tips don't touch the well bottom. [55] | |

| High Background [55] [56] | Insufficient washing | Follow appropriate washing procedures, including soak steps. Invert the plate on absorbent tissue and tap forcefully to remove residual fluid. [55] |

| Substrate exposed to light | Store substrate in the dark and limit exposure to light during the assay. [55] | |

| Contaminated buffers | Prepare fresh buffers. [56] | |

| Plate sealers reused | Use a fresh plate sealer for each incubation step to prevent cross-contamination. [55] | |

| Too Much Signal [55] [56] | Insufficient washing | Ensure thorough washing to remove unbound enzyme conjugate. [55] [56] |

| Incubation times longer than recommended | Adhere strictly to the protocol's specified incubation times. [55] | |

| Too much detection reagent | Check the dilution of enzyme-conjugated antibodies (e.g., streptavidin-HRP) and titrate if necessary. [56] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Data Quality and Reproducibility

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Replicate Data (Poor Duplicates) [55] [56] | Insufficient or uneven washing | Ensure consistent and thorough washing across all wells. If using an automatic washer, check that all ports are clean and unobstructed. [56] |

| Inconsistent pipetting | Check pipetting technique and calibrate pipettes regularly. [55] | |

| Plate sealers not used or reused | Always use a fresh plate sealer during incubations to prevent well-to-well contamination and evaporation. [55] [56] | |