Cell Type Annotation in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Powered Methods

Cell type annotation is a fundamental yet challenging step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, bridging computational clustering results to biological meaning by identifying the cell types present in a...

Cell Type Annotation in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Powered Methods

Abstract

Cell type annotation is a fundamental yet challenging step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, bridging computational clustering results to biological meaning by identifying the cell types present in a dataset. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of why annotation is critical for interpreting cellular heterogeneity. We explore the full spectrum of annotation methodologies, from manual expert curation and reference-based algorithms to the latest AI and large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Claude 3.5. The guide also addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, optimization strategies for complex data, and a comparative analysis of tool performance and validation techniques to ensure biologically accurate and reproducible results.

What is Cell Type Annotation? Defining the Cornerstone of scRNA-seq Analysis

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) research, cell type annotation represents the critical, non-trivial step of assigning biological identities to computationally derived cell clusters. This process transforms abstract groupings of cells, based on gene expression similarity, into biologically meaningful categories such as "T-cells" or "neurons." The core challenge lies in ensuring that these computational labels accurately reflect true biological states, a task complicated by biological complexity, technical artifacts, and the limitations of analytical methods. As the field progresses toward constructing comprehensive cellular atlases and applying these techniques in clinical contexts, the reliability of cell type annotation becomes paramount for generating biologically valid and reproducible insights [1] [2].

The Foundational Steps: From Raw Data to Cell Clusters

Before biological meaning can be assigned, scRNA-seq data must undergo extensive preprocessing to ensure subsequent analysis works with high-quality, technically comparable data. This foundational phase establishes the computational clusters that will later require biological interpretation.

Quality Control and Data Filtering

The initial quality control (QC) stage focuses on distinguishing viable cells from artifacts using three key metrics: the number of counts per barcode (count depth), the number of genes per barcode, and the fraction of counts from mitochondrial genes per barcode. The distributions of these QC covariates are examined for outlier barcodes that are subsequently filtered out through thresholding. Barcodes with low count depth, few detected genes, and high mitochondrial fraction often indicate dying cells or cells with broken membranes, while those with unexpectedly high counts and gene numbers may represent multiple cells captured together (doublets or multiplets). These three QC covariates must be considered jointly, as considering them in isolation can lead to misinterpretation; for example, cells with high mitochondrial counts might be involved in respiratory processes rather than being low quality [3].

Normalization, Feature Selection, and Dimensionality Reduction

Following QC, the data undergoes normalization to remove technical biases, such as those arising from varying count depths between cells. This enables meaningful comparison of gene expression across cells. Feature selection then identifies highly variable genes that contribute most to biological heterogeneity, reducing noise from genes with minimal variation. Dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) further condense the data while preserving essential biological signals. These steps collectively produce a refined dataset ready for clustering [3].

Clustering: Identifying Computational Cell Groups

Clustering algorithms group cells based on similarity in their gene expression profiles, forming the computational clusters that require biological annotation. Popular methods include Leiden and Louvain clustering, which operate on a graph of cells and their nearest neighbors. The resulting clusters are often visualized using UMAP or t-SNE embeddings, providing an intuitive visual representation of the relationships between cell groups. At this stage, however, these clusters remain computational entities without biological labels—they represent patterns in the data, not yet understood biological cell types [3] [4].

Table 1: Key Steps in Generating Computational Clusters

| Processing Step | Key Methods/Tools | Primary Purpose | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | Metrics: count depth, genes detected, mitochondrial fraction | Filter out low-quality cells and technical artifacts | Distinguishing biological signals from technical artifacts |

| Normalization | Log transformation, SCTransform | Remove technical biases (e.g., sequencing depth) | Choosing method appropriate for data characteristics |

| Feature Selection | Identification of highly variable genes | Focus analysis on biologically relevant genes | Retaining rare but important cell population markers |

| Dimensionality Reduction | PCA, UMAP, t-SNE | Visualize and simplify complex data structure | Interpreting distances in reduced dimensions |

| Clustering | Leiden, Louvain | Group cells by expression profile similarity | Determining optimal resolution parameters |

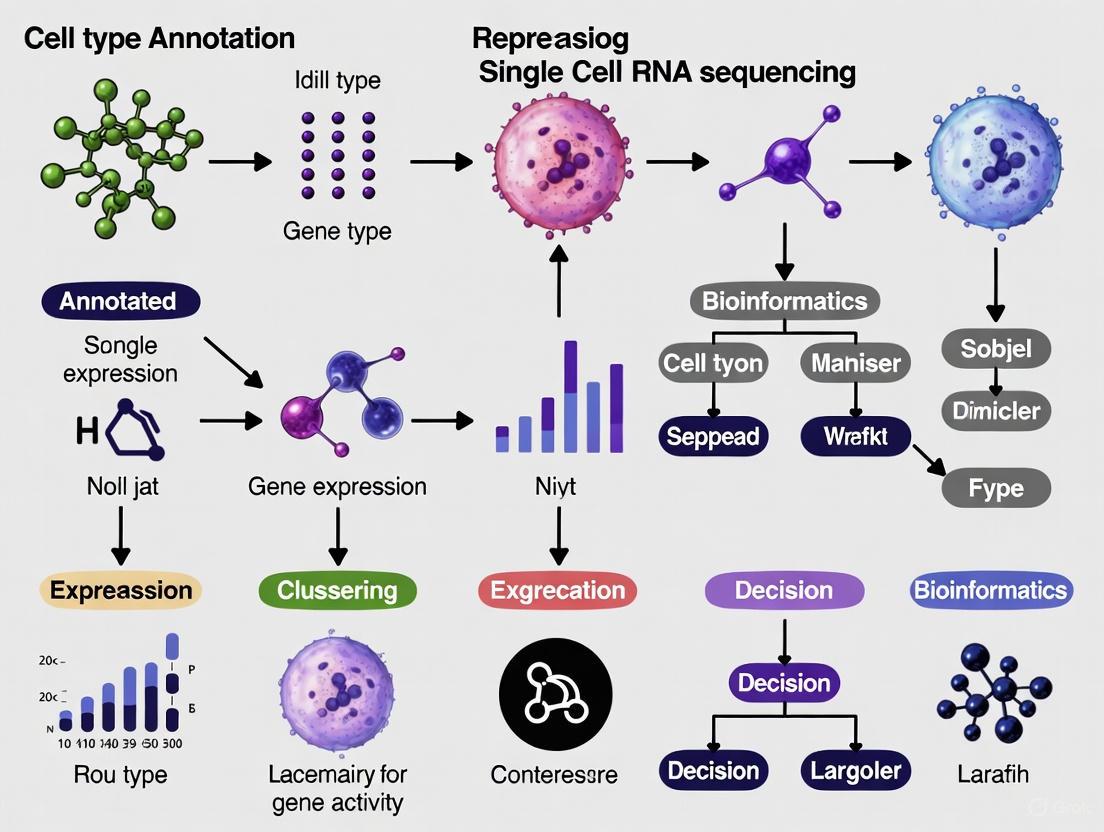

Figure 1: The Computational Workflow from Raw Data to Cell Clusters. This pipeline transforms raw sequencing data into computational groups that require biological annotation.

Methodological Frameworks for Cell Type Annotation

Reference-Based Annotation Approaches

Reference-based annotation leverages existing, well-annotated datasets as a ground truth to label new data. Tools such as SingleR and Azimuth perform this by comparing gene expression profiles between query cells and reference datasets, effectively transferring known labels from reference to query cells based on similarity. The Azimuth project provides annotations at different levels—from broad categories to detailed subtypes—allowing researchers to choose appropriate resolution. This approach works best when the reference data closely matches the biological context of the query data, though it may struggle with novel cell types not represented in the reference [2].

Marker Gene-Based Annotation

The traditional marker-based approach relies on known canonical marker genes to assign cell identities. Researchers examine differential expression between clusters and compare these patterns with established marker genes from literature (e.g., PECAM1 for endothelial cells). While intuitive, this method depends heavily on prior knowledge and curated marker databases, and can miss cell populations with unexpected marker combinations or novel cell types without established markers. It remains particularly valuable for validating and refining automated annotations [2].

Emerging AI-Driven Approaches

Recent advancements employ large language models (LLMs) to address annotation challenges. Tools like LICT (Large Language Model-based Identifier for Cell Types) leverage multiple LLMs in an integrated approach to improve annotation reliability. These systems utilize a "talk-to-machine" strategy where the model is queried with marker gene information, then provides annotations which are validated against expression patterns in the dataset. This iterative process enhances accuracy, particularly for challenging low-heterogeneity cell populations where traditional methods often struggle. A key innovation is the objective credibility evaluation, which assesses annotation reliability based on whether predicted marker genes are actually expressed in the annotated clusters, providing a reference-free validation mechanism [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Cell Type Annotation Methodologies

| Method | Key Tools/Platforms | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference-Based | SingleR, Azimuth | Standardized, efficient for known cell types | Limited for novel cell types; reference bias |

| Marker Gene-Based | Manual curation, literature mining | Biologically intuitive; good for validation | Depends on prior knowledge; incomplete coverage |

| AI-Driven | LICT, GPTCelltype | Adaptable; no reference needed; handles ambiguity | Complex implementation; training data dependencies |

| Hybrid Approaches | Combined use of multiple methods | Leverages complementary strengths | Time-consuming; requires expertise |

Practical Workflow: From Clusters to Biological Insight

An Integrated Annotation Pipeline

A robust annotation strategy typically combines multiple approaches. The process begins with reference-based annotation to establish preliminary labels, followed by marker gene validation to confirm or refine these assignments. For ambiguous clusters or populations that don't match known references, differential expression analysis identifies uniquely expressed genes that can be investigated further through literature searches and functional enrichment analysis. This multi-layered approach balances efficiency with biological plausibility, creating a safety net against the limitations of any single method [2].

Validation and Credibility Assessment

Regardless of the method used, validation is essential. The objective credibility evaluation strategy demonstrated by LICT provides a framework for assessing annotation reliability. In this approach, for each predicted cell type, representative marker genes are retrieved and their expression is analyzed in the corresponding clusters. An annotation is deemed reliable if more than four marker genes are expressed in at least 80% of cells within the cluster. This systematic validation helps distinguish robust annotations from uncertain ones, guiding researchers toward conclusions supported by their data [1].

Figure 2: Decision Workflow for Cell Type Annotation. This diagram outlines the logical process for moving from computational clusters to verified biological identities, incorporating multiple evidence sources and validation checkpoints.

Computational Platforms and Frameworks

Several integrated computational platforms form the backbone of modern scRNA-seq analysis. Seurat remains the R standard for versatility and integration, supporting multiple data modalities including spatial transcriptomics and CITE-seq data. Scanpy dominates large-scale scRNA-seq analysis in Python, with optimized architecture for handling millions of cells. The SingleCellExperiment ecosystem in Bioconductor provides a common format that underpins many specialized R tools, promoting reproducibility and method interoperability [5].

Reference Databases and Specialized Tools

Critical to annotation success are comprehensive reference databases and specialized tools. The Single Cell Expression Atlas offers a flexible pipeline and curated data. scRNASeqDB provides a database of human single-cell gene expression profiles. For specific analytical challenges, tools like Harmony efficiently correct batch effects; Velocyto enables RNA velocity analysis to infer cellular dynamics; and CellBender uses deep learning to remove ambient RNA contamination, cleaning data before annotation attempts [6] [7] [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Annotation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Platforms | Seurat, Scanpy, SingleCellExperiment | End-to-end analysis environments | General scRNA-seq analysis workflows |

| Reference Databases | Single Cell Expression Atlas, scRNASeqDB, Azimuth | Provide curated reference annotations | Reference-based annotation |

| Specialized Algorithms | Harmony, LICT, Velocyto, CellBender | Address specific analytical challenges | Batch correction, AI annotation, trajectory inference, noise reduction |

| Commercial Solutions | Trailmaker, BBrowserX, Partek Flow | User-friendly interfaces for non-bioinformaticians | Research settings with limited coding expertise |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of cell type annotation is rapidly evolving with several significant trends. Multi-model integration strategies are gaining traction, leveraging the complementary strengths of multiple LLMs to reduce uncertainty and increase annotation reliability. The "talk-to-machine" approach represents another advancement, iteratively enriching model input with contextual information to mitigate ambiguous or biased outputs. There is also increasing recognition of the need for objective credibility evaluation frameworks that assess annotation reliability based on marker gene expression within the input dataset, enabling reference-free, unbiased validation [1].

Spatial transcriptomics integration is becoming increasingly important, with tools like Squidpy enabling spatially informed single-cell analysis. This adds a crucial dimensional context to annotation decisions, helping resolve ambiguous cases where the same gene expression profile might have different meanings in different tissue locations. As these technologies mature, we can expect cell type annotation to move beyond purely transcriptomic definitions toward more integrated cellular identities incorporating spatial, epigenetic, and proteomic information [5].

Cell type annotation remains a core challenge in single-cell RNA sequencing research, serving as the critical bridge between computational patterns and biological meaning. Successful navigation of this challenge requires a multifaceted approach that combines computational rigor with biological expertise. No single method currently suffices for all scenarios—instead, researchers must strategically combine reference-based, marker-based, and emerging AI-driven approaches while implementing robust validation procedures.

The field continues to mature, with emerging trends pointing toward more integrated, spatially aware, and objectively validated annotation frameworks. What remains constant is the need for careful, critical assessment of cell type assignments—recognizing that these labels form the foundation for all subsequent biological interpretations and conclusions. By embracing a rigorous, multi-evidence approach to this fundamental task, researchers can ensure their computational clusters are faithfully translated into biologically meaningful identities that advance our understanding of cellular systems.

In the era of high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), automated cell type annotation tools have rapidly proliferated, offering the promise of rapid, reproducible cell classification. Despite these advances, manual annotation by domain experts continues to be regarded as the gold standard for identifying cell types and states in scRNA-seq data. This whitepaper examines the technical limitations of current computational methods and demonstrates how human expertise remains indispensable for interpreting complex biological contexts, identifying novel cell populations, and validating automated predictions. We present evidence from recent studies comparing annotation methodologies and provide a detailed framework for integrating expert knowledge with emerging computational tools to achieve the most biologically accurate results.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the profiling of gene expression at unprecedented resolution, revealing cellular heterogeneity and complex tissue organizations that were previously obscured in bulk sequencing approaches [8]. A fundamental step in interpreting scRNA-seq data is cell type annotation—the process of assigning identity labels to individual cells or clusters based on their transcriptomic profiles [9] [10].

The primary approaches to cell type annotation can be categorized into two paradigms: manual and automated methods. Manual annotation relies on expert knowledge to interpret differential gene expression patterns against established biological markers, while automated methods leverage computational algorithms to classify cells using reference datasets or marker databases [10] [11]. Despite the proliferation of automated tools, recent evaluations consistently reaffirm that "expert manual annotation is still considered the gold standard method for cell type assignment" [11]. This persistent preference stems from the nuanced understanding experts bring to interpreting complex gene expression patterns within specific biological contexts.

The Technical Limitations of Automated Annotation

Platform-Specific Biases and Data Quality Issues

Automated annotation methods face significant challenges related to technical variability across sequencing platforms. Different scRNA-seq technologies, such as 10x Genomics and Smart-seq, produce data with distinct characteristics due to their underlying sequencing principles [12]. The lower gene detection rate of high-throughput platforms like 10x Genomics may hinder the detection of key marker genes for rare cell types, while the higher sensitivity of full-length transcript methods like Smart-seq may reveal subpopulations that exceed the classification capacity of pre-trained models [12]. These technical differences exacerbate key challenges in scRNA-seq data, including sparsity, heterogeneity, and batch effects, which collectively compromise annotation consistency across platforms [12].

Challenges with Complex and Rare Cell Types

Automated methods particularly struggle with annotating closely related cell types and rare populations. As highlighted in evaluations of T cell phenotyping, while automated tools can differentiate major cell populations, "labelling T-cell subtypes remains problematic" [9]. This limitation becomes especially evident for unconventional T cells such as mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, natural killer T (NKT) cells, and γδ T cells, whose cellular profiles remain poorly understood and are often misclassified [9].

Table 1: Performance Challenges of Automated Annotation Methods

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Annotation Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Variability | Platform-specific biases in gene detection | Inconsistent marker gene detection across technologies |

| Data Quality Issues | High sparsity, dropout rates, batch effects | Reduced reliability in cross-study applications |

| Rare Cell Types | Limited representation in reference datasets | Frequent misclassification or complete oversight |

| Complex Lineages | Subtle transcriptional differences between subtypes | Inability to distinguish closely related cell states |

| Novel Populations | Dependence on existing classification schemas | Failure to identify previously uncharacterized cells |

Limitations of Reference Databases and Marker Genes

Automated methods heavily depend on the quality and comprehensiveness of reference databases and marker genes. Existing marker databases face significant limitations, including incomplete coverage, outdated data, and inconsistency across samples [12]. These limitations restrict their performance in handling novel cell types or rare cell populations. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of cellular phenotypes means that marker databases require continuous updating—a process that often lags behind biological discovery [12].

The Case for Manual Annotation: Precision Through Expert Knowledge

Interpretation of Complex Expression Patterns

Manual annotation leverages the pattern recognition capabilities and contextual knowledge of domain experts to interpret subtle expression patterns that automated methods frequently miss. Experts can integrate multi-layered biological information—including gradient expression changes, co-expression patterns, and biologically plausible cell state transitions—that extends beyond simple marker presence or absence [9] [11]. This nuanced interpretation is particularly valuable for distinguishing between closely related cell states and identifying transitional populations that don't fit neatly into predefined categories.

Identification of Novel Cell Types and States

A significant advantage of manual annotation is the capacity for discovery of novel cell types that are not represented in existing classification schemas or reference datasets. Unlike supervised automated methods that are constrained by their training data, human experts can recognize unusual expression patterns that may represent previously uncharacterized cell populations [11]. This discovery potential is especially important in exploratory research where the cellular landscape may be incompletely mapped.

Handling of Biological Context and Ambiguity

Expert annotators excel at incorporating tissue-specific context and recognizing biologically plausible cell type combinations. This contextual understanding enables appropriate interpretation of marker genes whose expression may vary across tissues or physiological states [11]. Furthermore, experts can recognize and appropriately handle ambiguous cases where cells exhibit mixed characteristics or exist in transitional states, avoiding the false precision that automated classification might impose [1].

Comparative Analysis: Manual vs. Automated Annotation

Recent systematic evaluations demonstrate the persistent performance gap between manual and automated annotation methods. In a comprehensive assessment of cell type annotation reliability, researchers found significant discrepancies between automated methods and manual annotations, particularly in less heterogeneous cell populations [1].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Annotation Approaches

| Annotation Method | Strengths | Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Annotation | High biological accuracy, context awareness, novel cell discovery | Time-intensive (20-40 hours for 30 clusters), subjective, requires expertise | Exploratory research, validation of automated results, complex cell types |

| Supervised Automated Methods (SingleR, CellTypist) | Fast, reproducible, handles large datasets | Limited to predefined cell types, requires high-quality reference data | Well-characterized tissues, initial screening of large datasets |

| Marker-Based Methods (scCATCH, SCSA) | Interpretable, uses established biological knowledge | Dependent on marker database quality, struggles with overlapping markers | Preliminary annotation when reference data is limited |

| LLM-Based Methods (GPT-4, LICT) | Broad knowledge base, no specialized training required | Unexplainable reasoning, potential for "AI hallucination" | Rapid initial assessment when expert unavailable |

Notably, a 2024 study evaluating GPT-4 for cell type annotation found that while it showed promise, it still required "validation of GPT-4's cell type annotations by human experts before proceeding with downstream analyses" due to concerns about reproducibility and potential for artificial intelligence hallucination [13]. Similarly, a 2025 study developing LICT (LLM-based Identifier for Cell Types) found that discrepancies between LLM-generated and manual annotations didn't necessarily indicate reduced reliability of manual methods, but rather highlighted cases where "manual annotations often exhibit inter-rater variability and systematic biases" [1].

Experimental Protocols for Manual Annotation

Standardized Workflow for Cluster-Based Annotation

The standard manual annotation workflow consists of a structured, iterative process that combines computational preprocessing with expert biological interpretation:

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control: Filter cells based on quality metrics (number of detected genes, total molecule count, mitochondrial gene percentage) to eliminate low-quality cells and technical artifacts [12].

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) followed by graph-based clustering (e.g., Seurat, Scanpy) to group cells with similar expression profiles [9] [14].

Differential Expression Analysis: Identify marker genes for each cluster using statistical tests (e.g., two-sided Wilcoxon test, Welch's t-test) comparing each cluster against all others [13] [11].

Expert Evaluation of Marker Genes: Systematically compare cluster-specific upregulated genes with canonical cell-type markers from literature and databases, prioritizing markers with known specificity and reliability [9] [11].

Contextual Validation: Assess the biological plausibility of preliminary annotations using spatial relationships (if available), trajectory inferences, and cross-referencing with established biological knowledge [11].

Iterative Refinement: Adjust annotations based on subclustering of heterogeneous populations and re-evaluation of ambiguous clusters [9].

Validation and Quality Assessment Protocols

To ensure annotation accuracy, experts employ multiple validation strategies:

- Multi-marker verification: Require concordant expression of multiple established marker genes rather than relying on single markers [9] [11]

- Cross-dataset validation: Compare annotations with independent datasets from similar tissues or conditions

- Negative marker assessment: Confirm absence of exclusion markers that define incompatible cell types

- Spatial validation: When available, verify that annotated cell types align with expected spatial distributions in tissue architecture [14]

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Type Annotation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker Gene Databases | CellMarker 2.0, PanglaoDB, CancerSEA | Provide curated lists of cell-type specific markers | Variable coverage across tissues; requires regular updating |

| Reference Atlases | Human Cell Atlas (HCA), Tabula Muris, Allen Brain Atlas | Offer comprehensive reference expression profiles | Platform-specific biases; limited rare cell representation |

| Analysis Platforms | Seurat, Scanpy, ACT (Annotation of Cell Types) | Enable data processing, visualization, and annotation | Different learning curves; varying algorithm implementations |

| Spatial Validation Tools | MERFISH, STARmap, seqFISH | Enable spatial confirmation of annotated cell types | Technical complexity; limited multiplexing capacity |

| Automated Annotation Tools | SingleR, CellTypist, scANVI | Provide rapid preliminary annotations | Require expert validation; variable performance across cell types |

Integrated Approaches: Combining Expert Knowledge with Computational Tools

The most effective annotation strategies leverage the complementary strengths of both manual and automated approaches through a structured integration:

The Hybrid Annotation Framework

Initial Automated Screening: Use supervised methods (SingleR, CellTypist) or LLM-based tools (GPT-4, LICT) to generate preliminary annotations [13] [10].

Expert-Led Refinement: Systematically review automated annotations, focusing on low-confidence predictions, rare populations, and biologically implausible assignments [9] [1].

Iterative Validation: Employ the "talk-to-machine" strategy where experts provide structured feedback to improve automated annotations through multiple cycles [1].

Objective Credibility Assessment: Implement quality metrics to evaluate annotation reliability, such as requiring expression of multiple marker genes in a high percentage of cells within clusters [1].

Emerging Best Practices

Current consensus recommends a "two-step annotation process" that involves "primary annotations of the gene expression clusters by automated algorithms, followed by expert-based manual interrogation of the cell populations" [9]. This hybrid approach balances efficiency with biological accuracy, ensuring that the final annotations are both reproducible and scientifically valid.

Manual annotation remains the gold standard for cell type identification in single-cell RNA sequencing research due to the irreplaceable role of expert knowledge in interpreting complex biological contexts, recognizing novel cell types, and validating automated predictions. While automated methods offer valuable scalability and reproducibility for initial screening, they cannot yet replicate the nuanced understanding that domain experts bring to annotation challenges. The most effective path forward lies in integrated approaches that leverage computational tools for efficiency while maintaining expert oversight for biological accuracy. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, the partnership between human expertise and computational power will be essential for unlocking the full potential of single-cell genomics in basic research and therapeutic development.

Cell type annotation is a fundamental and critical step in the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data. It is the process of assigning identity labels to individual cells based on their transcriptomic profiles, transforming clusters of computationally grouped cells into biologically meaningful categories [2]. This process is indispensable for understanding cellular composition and function within complex tissues, enabling researchers to decipher the cellular heterogeneity that underpins development, homeostasis, and disease [1] [15]. In the context of a broader thesis on scRNA-seq research, mastering cell type annotation is paramount, as accurate annotation forms the foundation upon which all subsequent biological interpretations and discoveries are built.

The core elements that enable this identification are marker genes, cellular heterogeneity, and transcriptomic profiles. Marker genes are genes that are uniquely or highly expressed in a specific cell type and serve as its molecular fingerprint. Cellular heterogeneity refers to the natural variation in gene expression between individual cells, even within a population that was once considered homogeneous. A cell's transcriptomic profile is the complete set of RNA molecules expressed from its genome at a specific point in time, providing a snapshot of its functional state [15]. Together, these concepts allow researchers to deconvolute complex tissues into their constituent cell types, identify novel cell states, and understand dynamic biological processes at an unprecedented resolution.

The Biological Foundation of Cell Identity

Defining Cell Types and States

Fundamentally, the concept of a "cell type" has evolved with technological advancements. Traditionally, biologists defined cell types based on morphology and physiology. The advent of antibody labeling introduced definition by cell surface markers, while RNA sequencing allowed for definition by gene expression profiles [2]. In the era of single-cell biology, cell identity is often context-dependent and can fall into several overlapping categories:

- Established Cell Types: These are well-characterized cells, such as osteocytes or endothelial cells, typically identified through reference datasets and distinct canonical markers (e.g., PECAM1 for endothelial cells) [2].

- Novel Cell Types: Biologically distinct clusters identified through differential expression that may represent previously undiscovered cell populations [2].

- Cell States: Transient, functional conditions of a cell, such as activation, stress, or a specific disease stage, which can be detected by scRNA-seq [2] [16].

- Developmental Stages: Cells captured along a continuum of differentiation, from progenitor to mature cell types, which can be ordered using trajectory inference algorithms [2].

The Central Role of Marker Genes

Marker genes are the practical tools used to assign these identities. A reliable marker gene exhibits consistently high expression in a target cell type and low expression in others. Their discovery and validation are central to annotation. For example, in a study of cervical cancer, single-cell transcriptomics identified distinct epithelial subpopulations based on their marker gene expression: one subpopulation was characterized by MMP1, SPRR1B, and KRT16, while another expressed immune-associated genes like CD74 and IL32 [17].

However, reliance on marker genes has limitations. Their expression can be dynamic, and no single marker is always perfectly specific. Therefore, annotation typically uses panels of marker genes rather than individual genes to improve confidence [2]. The scientific community has established several databases to catalog this knowledge, including CellMarker and PanglaoDB [12]. A key challenge is that these databases require continuous updating to incorporate new findings, a process that can be accelerated by deep learning models that help identify novel gene combinations characteristic of specific cell types [12].

Technical Workflow: From Raw Data to Annotation

The journey from a tissue sample to an annotated single-cell dataset is a multi-stage process involving both wet-lab and computational steps. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and the central role of annotation.

Experimental Protocols and Reagent Solutions

Generating high-quality single-cell data requires careful experimental planning and selection of appropriate platforms. The table below summarizes key commercial solutions for cell capture and library generation.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

| Commercial Solution | Capture Platform | Throughput (Cells/Run) | Capture Efficiency | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10× Genomics Chromium | Microfluidic oil partitioning | 500 – 20,000 | 70–95% | Industry standard; requires specific hardware [18]. |

| BD Rhapsody | Microwell partitioning | 100 – 20,000 | 50–80% | Compatible with both cells and nuclei [18]. |

| Parse Evercode | Multiwell-plate | 1,000 – 1M | >90% | Very low cost per cell; requires high cell input [18]. |

| Fluent/PIPseq (Illumina) | Vortex-based oil partitioning | 1,000 – 1M | >85% | No microfluidics hardware; flexible for large cell sizes [18]. |

The choice of platform depends on the research question, sample type, and desired throughput. For instance, droplet-based systems like 10× Genomics are ideal for profiling tens of thousands of cells, while plate-based systems like Parse BioScience offer a lower cost per cell for massive-scale projects [18]. A critical preliminary decision is whether to sequence single cells or single nuclei. Single cells provide greater mRNA content, generally yielding more robust gene expression data. Single nuclei are advantageous for difficult-to-dissociate tissues (e.g., neurons) and are compatible with multi-omics assays that also profile open chromatin (ATAC-seq) [18].

Computational Preprocessing Prior to Annotation

Before annotation can begin, raw sequencing data must be rigorously processed to ensure reliability. This preprocessing pipeline involves several standardized steps [19] [12]:

- Quality Control (QC): Cells are filtered based on metrics like the number of genes detected, total molecule count, and the proportion of mitochondrial gene expression. High mitochondrial content often indicates stressed or dying cells [19] [12].

- Doublet Detection: Algorithms like DoubletFinder or Scrublet are used to identify and remove droplets that contain two or more cells, which can appear as artificial cell types [19].

- Normalization: Technical variations in sequencing depth between cells are corrected to make their expression profiles comparable.

- Batch Effect Correction: When data is generated across multiple sequencing runs or platforms, tools like Harmony or ComBat are used to remove non-biological technical differences [2] [19].

- Clustering: Dimensionality reduction (e.g., UMAP, t-SNE) is performed, and cells are grouped into clusters based on the similarity of their transcriptomic profiles. These clusters represent putative cell types or states and are the direct input for the annotation process [2] [19].

Methodologies for Cell Type Annotation

Traditional and Reference-Based Approaches

The practical steps of cell type identification often involve a combinatorial approach that integrates automated methods with expert knowledge [2].

- Reference-Based Annotation: This method involves aligning the gene expression profiles of query cells against a pre-annotated reference atlas. Tools like SingleR and Azimuth calculate the correlation between a single cell's expression profile and the average profiles of known cell types in the reference, assigning the label of the best-matching type [2] [13]. The Azimuth project, for instance, provides annotations at different levels of resolution, from broad categories to detailed subtypes.

- Manual Refinement: Automated methods are not infallible. Manual refinement is a crucial step where biologists fine-tune annotations by verifying the expression patterns of canonical marker genes across clusters, performing differential gene expression analysis to find unique signatures, and consulting the scientific literature [2]. This process integrates deep biological expertise to correct misclassifications and identify novel populations.

The Emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs)

A recent and powerful advancement in annotation is the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4. These models do not rely on reference datasets; instead, they use their vast training on public text and data to annotate cell types directly from a list of marker genes provided by the researcher [1] [13].

The process is straightforward: a researcher inputs the top marker genes for a cluster (e.g., "CD3E, CD3D, CD2") into the LLM with a prompt, and the model returns a predicted cell type (e.g., "T cell") [13]. Studies have shown that GPT-4 generates annotations with strong concordance to manual expert annotations, considerably reducing the effort and expertise required [13]. To address limitations such as performance on low-heterogeneity datasets, next-generation tools like LICT (Large Language Model-based Identifier for Cell Types) have been developed. LICT employs sophisticated strategies:

- Multi-model integration: Leveraging several top-performing LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Claude 3) and selecting the best result to improve accuracy [1].

- "Talk-to-machine" strategy: An iterative process where the model is asked to provide marker genes for its prediction, which are then checked against the dataset. If the validation fails, the model is queried again with the new evidence, refining its annotation [1].

- Objective credibility evaluation: This strategy assesses the reliability of an annotation by checking if the model-predicted marker genes are actually expressed in the cluster, providing a reference-free measure of confidence [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Automated Cell Type Annotation Methods

| Method Category | Examples | Underlying Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker Gene-Based | Manual Curation | Matching DEGs to known markers from literature/databases. | Intuitive; high biological interpretability. | Labor-intensive; dependent on pre-existing knowledge [2]. |

| Reference-Based Correlation | SingleR, Azimuth | Calculating similarity to a labeled reference dataset. | Objective; fast for well-defined tissues. | Accuracy depends on reference quality and completeness [2] [13]. |

| Supervised Classification | Various ML classifiers | Training a model on reference data to predict labels. | Can be highly accurate if training data is good. | Poor generalization to cell types not in the training set [12]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | GPTCelltype, LICT | Using pre-trained knowledge to infer cell type from marker lists. | No reference needed; broad knowledge base; high accuracy [1] [13]. | "Black box" nature; potential for AI hallucination; requires validation [1] [13]. |

The following diagram illustrates the advanced, iterative workflow of the LICT tool, which represents the cutting edge in LLM-based annotation.

Interpreting Results and Advanced Applications

Resolving Discrepancies and Assessing Confidence

Discrepancies between automated annotations (including LLM-based ones) and manual expert labels do not automatically imply the automated method is wrong. Expert annotations can suffer from inter-rater variability and inherent biases [1]. The objective credibility evaluation strategy in LICT addresses this by providing a data-driven measure of reliability. For instance, in a stromal cell dataset, 29.6% of LLM-generated annotations were deemed credible based on marker gene evidence, whereas none of the manual annotations met the same credibility threshold, suggesting the LLM may have provided more accurate labels in these cases [1].

Applications in Disease Research: The Case of Cancer

Cell type annotation is powerful for unraveling the complexity of disease. In cervical cancer, annotation of scRNA-seq data revealed extensive heterogeneity within malignant epithelial cells, identifying subpopulations with distinct genomic and transcriptomic signatures, such as a hypoxic subpopulation and a proliferative subpopulation [17]. Similarly, in inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), annotation was key to characterizing it as an immunologically "cold" tumor, revealing a significant reduction in immune cells like CD45+ cells and a suppressed immune microenvironment, which informs potential immunotherapy strategies [16].

Cell type annotation, powered by the core concepts of marker genes, cellular heterogeneity, and transcriptomic profiles, is the linchpin of single-cell RNA sequencing research. The field is rapidly evolving, moving from purely manual curation to a hybrid of sophisticated computational methods. While reference-based and supervised methods remain highly valuable, the emergence of LLM-based tools like LICT offers a promising, reference-free alternative that leverages vast biological knowledge. Regardless of the method, a gold-standard principle remains: the most robust annotations are achieved by combining computational power with deep biological expertise and, where possible, orthogonal experimental validation. This integrated approach ensures that the names we assign to cells truly reflect their biological identity, enabling meaningful discoveries in health and disease.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biology by enabling the investigation of transcriptional programs at the ultimate level of resolution. However, the analytical potential of this technology is constrained by substantial data challenges, primarily sparsity, technical noise, and batch effects. These technical artifacts profoundly impact downstream analyses, including the crucial task of cell type annotation. This technical guide examines the nature, causes, and consequences of these data characteristics, providing structured methodologies and computational strategies to mitigate their effects. By framing these issues within the context of cell type annotation—the process of bridging observed cellular clusters with existing biological knowledge—we equip researchers with robust frameworks for generating biologically meaningful insights from complex single-cell datasets.

Single-cell RNA sequencing technology has emerged as a powerful method for characterizing gene expression profiles at the individual cell level, providing unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues [8]. Since its conceptual breakthrough in 2009, scRNA-seq has enabled the classification and characterization of cells at the transcriptome level, allowing identification of rare but functionally important cell populations [8]. The technology has evolved from processing few cells per experiment to hundreds of thousands of cells, with costs dramatically decreasing while automation and throughput have significantly increased [8].

Despite these advancements, scRNA-seq data present unique analytical challenges that distinguish them from bulk RNA sequencing approaches. Three characteristics particularly impact data quality and interpretation: (1) Sparsity - an excess of zero counts arising from both biological and technical factors; (2) Noise - high technical variability from minute starting material and amplification; and (3) Batch effects - systematic technical variations between experiments conducted at different times, by different operators, or with different protocols [20] [21]. These artifacts can confound biological variations of interest during data integration and may hamper downstream analyses, potentially making results inconclusive [20].

The process of cell type annotation—matching observed cell clusters to known biological identities—is particularly vulnerable to these data challenges. As the fundamental step in scRNA-seq analysis that bridges computational findings with biological meaning, accurate annotation requires careful consideration of data quality and appropriate application of correction methods [22]. This guide examines these data characteristics in depth and provides practical experimental and computational strategies to address them.

Understanding Core Data Characteristics

Data Sparsity: Causes and Consequences

Sparsity in scRNA-seq data manifests as an abundance of zero counts in the gene expression matrix, with approximately 80% of gene expression values typically being zero [23]. This sparsity arises from both biological factors (genuine absence of transcript expression) and technical factors (failure to detect expressed transcripts due to limited sensitivity). The distinction between these "biological zeros" and "technical zeros" (also known as dropout events) is methodologically challenging but crucial for accurate analysis.

The impact of sparsity on differential expression analysis is substantial. Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that data sparsity substantially impacts the performance of differential expression methods [24]. Sparsity reduces power to detect truly differentially expressed genes, particularly those with modest fold changes or low abundance. Studies comparing scRNA-seq with bulk RNA-seq found that clusters require 2,000 or more cells to identify the majority of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that show modest differences in bulk RNA-seq analysis [25]. Conversely, clusters with as few as 50-100 cells may be sufficient for identifying DEGs with extremely small p-values or high transcript abundance (>200 TPM) [25].

Table 1: Impact of Cell Number on DEG Detection in scRNA-seq

| Cell Number per Cluster | Recapitulation of Modest DEGs | Recapitulation of High-Abundance DEGs | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50-100 cells | <10% | >50% | Detection of high-abundance, strongly significant DEGs |

| 1,000 cells | ~40% | >70% | Moderate-powered DEG detection |

| 2,000+ cells | >50% | >80% | Comprehensive DEG detection including modest differences |

Technical Noise and Variability

Technical noise in scRNA-seq data originates from multiple sources throughout the experimental workflow. The minimal RNA quantity from individual cells creates substantial amplification bias during reverse transcription and cDNA amplification [8]. Two primary amplification strategies are employed: polymerase chain reaction (PCR-based) and in vitro transcription (IVT-based), each introducing distinct noise profiles [8]. PCR represents a non-linear amplification process that can preferentially amplify certain transcripts, while IVT provides linear amplification but requires an additional round of reverse transcription, potentially introducing 3' coverage biases [8].

Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were introduced to address amplification-associated biases, enabling quantitative correction by barcoding individual mRNA molecules during reverse transcription [8]. UMI incorporation improves the quantitative nature of scRNA-seq by effectively eliminating PCR amplification bias and enhancing reading accuracy. However, even with UMIs, substantial technical noise persists due to cell-to-cell variation in capture efficiency, amplification efficiency, and sequencing depth.

Additional noise sources include "artificial transcriptional stress responses" induced by tissue dissociation procedures. Studies have confirmed that protease dissociation at 37°C can induce expression of stress genes, introducing technical artifacts and causing inaccurate cell type identification [8]. Dissociation at 4°C or utilization of single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) has been suggested to minimize these isolation procedure-induced gene expression changes [8].

Batch effects represent consistent technical variations in gene expression patterns induced by differences in experimental conditions rather than biological differences [23]. These effects can originate from multiple sources including different sequencing platforms, timing, reagents, laboratory conditions, or operators [21] [23]. In large-scale projects where data generation across multiple batches is inevitable, these technical variations can mask underlying biology or introduce spurious structure, potentially leading to misleading conclusions [21].

Several visualization approaches help identify batch effects in scRNA-seq datasets. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of raw data can reveal batch effects through examination of top principal components, where sample separation reflects batch identity rather than biological sources [23]. Similarly, clustering analysis visualized on t-SNE or UMAP plots typically shows cells from different batches clustering separately rather than grouping by biological similarity when batch effects are present [23]. Quantitative metrics like normalized mutual information (NMI), adjusted rand index (ARI), and k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET) provide objective measures of batch effect strength and correction efficacy [23].

Table 2: Batch Effect Detection and Quantification Methods

| Method Category | Specific Approaches | Key Output | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visualization Methods | PCA, t-SNE, UMAP | Low-dimensional embeddings | Visual separation of batches indicates batch effects |

| Clustering-based Metrics | Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) | Numerical scores (0-1) | Higher values indicate better batch mixing |

| Neighborhood-based Tests | k-BET (k-nearest neighbor batch effect test) | p-values, rejection rates | Lower rejection rates indicate successful integration |

| Graph-based Metrics | Graph iLISI, PCR (batch) | Numerical scores | Higher scores indicate better integration quality |

Experimental Protocols for Data Quality Control

Single-Cell Isolation and Library Preparation

The single-cell isolation process represents a critical source of technical variation. The most common techniques include limiting dilution, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), magnetic-activated cell sorting, microfluidic systems, and laser microdissection [8]. The key outcome is that each single cell must be captured in an isolated reaction mixture where all transcripts from that cell are uniquely barcoded after conversion to complementary DNAs (cDNA) [8].

For tissues sensitive to dissociation stress, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides an alternative approach that minimizes artificial transcriptional responses. snRNA-seq has proven particularly useful for brain tissues, which are difficult to dissociate into intact cells, as well as muscle, heart, kidney, lung, pancreas, and various tumor tissues [8]. However, researchers should note that snRNA-seq only captures nuclear transcripts, potentially missing biological processes related to mRNA processing, RNA stability, and metabolism [8].

Following cell isolation, library preparation involves critical choices between amplification methods. PCR-based strategies include SMART technology (taking advantage of transferase and strand-switch activity of Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus reverse transcriptase) or alternative methods connecting the 5' end of cDNA with poly(A) or poly(C) to build common adaptors [8]. IVT-based approaches provide linear amplification but introduce additional procedural steps. The selection between these strategies should consider the specific biological questions, required throughput, and sensitivity requirements.

Quality Assessment Workflows

A robust quality assessment workflow should include both pre- and post-correction evaluation steps. Pre-correction assessment identifies potential batch effects and data quality issues, while post-correction validation ensures that correction methods have not introduced artifacts or removed biological signal.

Pre-correction Quality Assessment Protocol:

- Sequencing Depth Evaluation: Calculate the average reads per cell and distribution across cells. Exclude cells with extremely low sequencing depth (typically <500-1,000 reads per cell depending on protocol).

- Gene Detection Analysis: Assess the number of genes detected per cell. Filter cells with unusually low gene counts (potential empty droplets) or unusually high counts (potential multiplets).

- Mitochondrial Gene Content: Calculate the percentage of mitochondrial reads. High percentages (>10-20%) may indicate stressed or dying cells.

- Batch Effect Visualization: Generate PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP plots colored by batch identity to visually assess batch separation.

- Quantitative Batch Metrics: Compute batch effect metrics such as k-BET or ARI to quantitatively measure batch effect strength.

Post-correction Validation Protocol:

- Visual Inspection: Regenerate dimensionality reduction plots (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP) colored by batch to confirm batch mixing.

- Biological Preservation Tests: Verify that known biological signals (cell type markers, experimental conditions) remain distinct after correction.

- Quantitative Integration Metrics: Recompute batch effect metrics to quantify improvement in integration quality.

- Differential Expression Consistency: Check consistency of differential expression results before and after correction for known biological effects.

- Overcorrection Checks: Examine whether canonical cell type markers remain detectable and whether cluster-specific markers show expected patterns.

Diagram Title: scRNA-seq Quality Assessment Workflow

Computational Correction Strategies

Batch Effect Correction Algorithms

Multiple computational approaches have been developed to address batch effects in scRNA-seq data, each with distinct theoretical foundations and implementation considerations. These methods can be broadly categorized into several classes:

Nearest Neighbor-based Methods: Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) correction identifies pairs of cells from different batches that are mutually the most similar in expression space, assuming these represent the same cell type [21] [24]. The observed differences between MNN pairs provide an estimate of the batch effect, which is applied to correct the entire dataset. The MNN approach does not require identical population composition across batches and only needs a subset of shared cell types [21]. Related methods include Scanorama, which searches for MNNs in dimensionally reduced spaces and uses similarity-weighted approach for integration [24] [23].

Deep Learning Approaches: Methods like scGen employ variational autoencoders (VAEs) trained on reference data to correct batch effects in new datasets [20] [23]. Adversarial Information Factorization (AIF) uses a conditional variational autoencoder architecture combined with adversarial training to factorize batch effects from biological signals [20]. The encoder learns to separate biological information (in a latent vector) from batch information, while a discriminator ensures the latent representation is free of batch effects [20]. These methods have demonstrated strong performance in scenarios with low signal-to-noise ratio and batch-specific cell types [20].

Matrix Factorization Methods: LIGER (Linked Inference of Genomic Experimental Relationships) employs integrative non-negative matrix factorization to identify both batch-specific and shared factors [23]. The method establishes a shared factor neighborhood graph to connect cells with similar neighborhoods, then normalizes factor loading quantiles to a reference dataset to accomplish batch correction [23].

Other Statistical Approaches: Harmony utilizes PCA for dimensionality reduction, then iteratively removes batch effects by clustering similar cells across batches and calculating correction factors for each cell [23]. ComBat, originally developed for bulk RNA-seq, uses empirical Bayes shrinkage to stabilize batch effect estimates, sharing information across genes [24].

Table 3: Batch Effect Correction Method Comparison

| Method | Underlying Algorithm | Key Strength | Limitations | Output Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNN Correct | Mutual Nearest Neighbors | Does not require identical population composition | Computationally intensive for large datasets | Corrected expression matrix |

| Harmony | Iterative clustering with PCA | Efficient for large datasets | Primarily provides embeddings | Low-dimensional embeddings |

| Scanorama | Mutual Nearest Neighbors | Handles complex datasets well | May require parameter tuning | Corrected expression matrix and embeddings |

| scGen | Variational Autoencoder | Strong with batch-specific cell types | Requires reference dataset | Corrected expression matrix |

| LIGER | Non-negative Matrix Factorization | Identifies shared and dataset-specific factors | Complex implementation | Low-dimensional factors |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes | Stabilizes estimates with limited replicates | Assumes similar population composition | Corrected expression matrix |

| AIF | Adversarial Conditional VAE | Robust to noise and specific cell types | Complex training procedure | Corrected expression matrix |

Differential Expression Analysis with Batch Considerations

Benchmarking studies have evaluated 46 workflows for differential expression analysis of single-cell data with multiple batches, revealing that batch effects, sequencing depth, and data sparsity substantially impact performance [24]. Three primary integrative strategies exist for handling batch effects in differential expression analysis:

Batch Effect Corrected Data Analysis: Applying differential expression tests to data after batch effect correction. Studies show this approach rarely improves analysis for sparse data, with one exception being scVI-improved limmatrend [24].

Batch Covariate Modeling: Including batch as a covariate in statistical models while using uncorrected data. This approach overall improves methods like MAST, ZINB-WaVE-edgeR, DESeq2, and limmatrend for large batch effects, with MASTCov and ZWedgeR_Cov showing among the highest performances [24].

Meta-analysis Methods: Performing differential expression analysis separately for each batch then combining results using methods like weighted Fisher, fixed effects model, or random effects model. These approaches generally do not improve upon naïve DE methods in benchmarking studies [24].

For low-depth data, single-cell techniques based on zero-inflation models tend to deteriorate in performance, whereas analysis of uncorrected data using limmatrend, Wilcoxon test, and fixed effects model performs well [24]. As depth decreases, the relative performance of Wilcoxon test and fixed effects model for log-normalized data improves, while the benefit of covariate modeling diminishes for very low depths [24].

Diagram Title: DE Strategy Selection Based on Data Characteristics

Cell Type Annotation Despite Data Challenges

Cell type annotation represents the critical bridge between computational clustering results and biological interpretation, directly impacted by data quality issues. Recent advancements include the application of large language models like GPT-4, which can accurately annotate cell types using marker gene information, generating annotations with strong concordance with manual annotations [13]. When evaluated across hundreds of tissue and cell types, GPT-4's annotations fully or partially match manual annotations in over 75% of cell types in most studies and tissues [13].

However, annotation reliability depends heavily on data quality. Performance decreases with small cell populations (≤10 cells), likely due to limited information, and struggles with cell types lacking distinct gene sets, such as B lymphoma cells [13]. GPT-4 also tends to provide higher granularity than manual annotations in some cases, such as distinguishing fibroblasts and osteoblasts within stromal cell classifications [13].

Traditional automated methods like SingleR and ScType require additional processing of gene expression matrices and generally show lower agreement with manual annotations compared to GPT-4 approaches [13]. Regardless of the annotation method, validation by domain experts remains crucial, particularly given the potential for artificial intelligence "hallucination" and the undisclosed nature of GPT-4's training corpus [13].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Isolation Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium, DNBelab C4, SMART-seq | Isolate individual cells for sequencing | Throughput, cell viability, recovery efficiency |

| Library Preparation Kits | Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3', SMART-seq2, CEL-seq2 | Convert RNA to sequencing-ready libraries | Sensitivity, UMI incorporation, cost per cell |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Various sequences incorporated during RT | Barcode individual mRNA molecules | Enable quantitative correction for amplification bias |

| Cell Viability Assays | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), Trypan blue exclusion | Assess cell integrity before processing | Impact on gene expression, compatibility with platform |

| Batch Effect Correction Software | Seurat, Harmony, Scanorama, scVI, scGen | Computational removal of technical variations | Compatibility with data type, computational requirements |

| Cell Type Annotation Tools | GPTCelltype, SingleR, ScType, CellMarker2.0 | Automate cell type identification | Reference database comprehensiveness, accuracy |

| Differential Expression Packages | DESeq2, edgeR, MAST, limma, Wilcoxon test | Identify statistically significant expression changes | Sensitivity to sparsity, batch effect handling |

The characteristics of scRNA-seq data—sparsity, noise, and batch effects—present significant challenges that directly impact the reliability of biological interpretations, particularly for cell type annotation. These technical artifacts can obscure true biological signals, leading to inaccurate cell type identification and differential expression results. Through careful experimental design, appropriate computational correction, and rigorous validation, researchers can mitigate these issues. The field continues to evolve with novel approaches like adversarial deep learning for batch correction and large language models for annotation, offering promising directions for more robust analysis. As single-cell technologies become more widely adopted, including in underrepresented populations and resource-limited settings, addressing these fundamental data challenges becomes increasingly critical for generating biologically meaningful and reproducible insights.

From Manual Curation to AI Assistants: A Guide to Annotation Methods

Cell type annotation is a foundational step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, enabling researchers to determine the identity and function of individual cells within a complex tissue. This process transforms clusters of cells, identified computationally based on gene expression similarity, into biologically meaningful cell types and states [26]. Manual annotation, which leverages existing biological knowledge from marker gene databases and researcher expertise, is widely considered the gold standard against which automated methods are often benchmarked [1] [27]. While labor-intensive, this method provides critical, biologically grounded interpretations that are essential for understanding cellular composition, heterogeneity, and function in development, health, and disease [28] [26].

The fundamental challenge of cell type annotation arises from two biological realities: first, gene expression levels exist on a continuum, and second, transcriptional differences do not always equate to functional differences [28]. Manual annotation addresses this by integrating prior knowledge with dataset-specific evidence to assign cell identities, a process that remains indispensable for generating reliable biological insights from scRNA-seq data [27].

Foundational Concepts and Workflow

The process of manual cell type annotation relies on establishing connections between the gene expression patterns observed in scRNA-seq data clusters and previously documented cell type signatures. This typically follows a structured workflow that integrates computational outputs with biological knowledge.

The Manual Annotation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for manual cell type annotation, from data preparation to final annotation and validation.

Key Preparatory Steps

Before beginning manual annotation, specific computational preprocessing steps are essential:

- Clustering Analysis: Cells are grouped based on gene expression similarity using algorithms such as Louvain or Leiden [29]. These clusters form the basic units for annotation.

- Differential Expression Analysis: For each cluster, statistical tests identify genes that are significantly upregulated compared to all other cells. These potential marker genes are the primary evidence for cell identity [28].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like t-SNE or UMAP provide visual representations of cell relationships in two dimensions, helping annotators assess cluster quality and relationships [30].

Manual annotation relies heavily on curated databases that compile cell type-specific marker genes from published literature. The table below summarizes key resources available to researchers.

Table 1: Key Marker Gene Databases for Manual Cell Type Annotation

| Database Name | Key Features | Species Coverage | Update Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| singleCellBase | Manually curated; 9,158 entries; 1,221 cell types; 8,740 gene markers; hierarchical cell type structure [27] | 31 species across Animalia, Protista, Plantae [27] | 2023 |

| CellMarker 2.0 | Manually curated from >100k publications; user-friendly interface; includes pseudogenes and lncRNAs [28] | Human and mouse [28] | Last updated September 2022 [28] |

| PanglaoDB | Web server for exploration of mouse and human scRNA-seq data [27] | Human and mouse [27] | 2019 |

| MSigDB | Curated datasets C8 (human) and M8 (mouse); regularly updated by funded curators [28] | Human and mouse [28] | Regularly updated |

| Tabula Muris | Repository of scRNA-seq data from mouse; 20 different organs and tissues [28] | Mouse [28] | Highly cited resource |

These databases vary in scope and specialization. singleCellBase offers the broadest species coverage, while CellMarker 2.0 provides extensive curation from a large publication base. Selection should be guided by the organism and tissue type under investigation [28] [27].

Experimental and Methodological Framework

Step-by-Step Annotation Protocol

The manual annotation process follows a systematic approach to ensure accurate and reproducible results:

- Cluster Identification: Begin with well-defined cell clusters from computational analysis. High-quality clustering is essential, as poor separation can lead to ambiguous annotations [29].

- Marker Gene Extraction: Obtain the list of top differentially expressed genes for each cluster, typically ranked by statistical significance (adjusted p-value) and fold-change [28].

- Database Query: Cross-reference the top marker genes (typically 5-10 genes per cluster) against marker gene databases. For example, search "CD8A" in singleCellBase to confirm its association with CD8+ T cells in humans [27].

- Multi-Gene Validation: Avoid relying on a single marker gene. Instead, confirm that multiple known markers for a cell type are consistently expressed in the cluster. For instance, a plasma cell cluster should express both SDC1 (CD138) and MZB1 [28].

- Negative Marker Confirmation: Verify the absence of key markers for other cell types. A neuronal cluster should lack expression of immune cell markers like PTPRC (CD45) [28].

- Literature Correlation: Conduct targeted literature searches to confirm that the identified marker combination specifically identifies the proposed cell type in the relevant tissue context [28].

- Iterative Refinement: Revisit ambiguous annotations by examining additional markers or refining cluster resolution. Some cell subtypes may require subclustering for precise identification [28].

- Expert Consultation: Discuss challenging annotations with domain experts, particularly for specialized tissues or rare cell types [28].

- Experimental Validation: Where possible, confirm annotations using orthogonal methods such as fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) with antibody staining or in situ hybridization [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq and Annotation

| Reagent/Material | Function in scRNA-seq and Annotation |

|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Droplet-based single cell capture system for high-throughput scRNA-seq library preparation [26] |

| SMARTer Chemistry | For mRNA capture, reverse transcription, and cDNA amplification in scRNA-seq protocols [26] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short nucleotide barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules to correct for PCR amplification bias and enable accurate transcript counting [26] [30] |

| Fluorescent-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Instrument for isolating specific cell populations based on surface protein markers for validation studies [8] |

| Antibody Panels (Oligo-conjugated) | For CITE-seq and similar technologies that simultaneously measure surface protein expression and transcriptome in single cells [29] |

| Poly[T] Primers | Reverse transcription primers that specifically capture polyadenylated mRNA molecules, excluding ribosomal RNAs [26] |

Interpretation and Quality Assessment

Addressing Annotation Challenges

Even with rigorous methodology, manual annotation presents several challenges that require careful interpretation:

- Low-Heterogeneity Cell Populations: Cell types with similar transcriptional profiles (e.g., developmental intermediates, stromal subtypes) pose particular difficulties. In such cases, LLM-based tools like LICT have demonstrated higher annotation credibility compared to manual annotations in some benchmarks [1].

- Novel Cell Populations: Some clusters may not match known cell types, potentially representing novel cell states or types. These should be clearly labeled as "unknown" or given descriptive names based on their marker expression until further validation [28].

- Conflicting Evidence: Discrepancies between different database sources or between database information and dataset-specific expression patterns require resolution through additional literature review or experimental validation [28].

Credibility Assessment Framework

Recent advancements provide objective frameworks to evaluate annotation reliability. The LICT tool, for example, uses a credibility evaluation strategy where an annotation is considered reliable if more than four marker genes are expressed in at least 80% of cells within the cluster [1]. This quantitative approach can complement expert judgment, particularly for challenging annotations.

Manual annotation remains an essential methodology in single-cell genomics, providing biologically grounded cell identities that form the foundation for downstream analysis. While increasingly complemented by automated tools and AI-based approaches, the integration of marker gene databases and biological expertise continues to offer unparalleled interpretative power [1] [27]. As the field advances, the manual annotation process is evolving to incorporate more quantitative credibility assessments [1] while maintaining its core strength: the nuanced integration of established biological knowledge with dataset-specific evidence. This approach ensures that cell type annotations reflect genuine biological reality rather than computational artifacts, enabling more reliable discoveries in biomedical research and drug development.

Cell type annotation is a foundational step in the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data. This process involves classifying individual cells into specific biological categories based on their gene expression profiles, transforming complex molecular data into biologically meaningful insights. In traditional scRNA-seq analysis, researchers manually annotate cell clusters by comparing highly expressed genes with known cell type marker genes, a process that is both time-consuming and subjective, requiring significant expert knowledge. The emergence of spatial transcriptomics technologies, which add a spatial dimension to gene expression data, has further heightened the importance of accurate cell type identification. These technologies can be broadly categorized into sequencing-based platforms, such as 10x Visium and Slide-seq, which profile the whole transcriptome but typically at multi-cell resolution, and imaging-based platforms, including 10x Xenium and MERSCOPE, which achieve true single-cell resolution while measuring a targeted panel of several hundred genes [31] [32].

Reference-based cell type annotation methods automate this classification process by leveraging existing, expertly annotated datasets. These methods transfer cell type labels from a reference dataset (often a comprehensive scRNA-seq atlas) to a query dataset (new experimental data) based on similarity in gene expression patterns. This approach offers significant advantages over manual annotation by increasing throughput, standardization, and reproducibility, while effectively leveraging the knowledge embedded in well-curated reference datasets. Tools such as SingleR, Azimuth, RCTD, scPred, and scmap have been developed to perform this task, each implementing distinct computational strategies to achieve accurate cell type transfer [31] [32] [33].

Core Mechanisms of Reference-Based Annotation

The Fundamental Principles of Label Transfer

Reference-based annotation methods fundamentally operate by comparing the gene expression profile of each cell in a query dataset against profiles in a reference dataset. The core assumption is that cells of the same type will exhibit similar expression patterns across a defined set of genes, despite technical variations between experiments. This process involves several key steps: data preprocessing (normalization, gene matching), similarity calculation between query cells and reference data, and label assignment based on optimal matches. Performance depends critically on the quality and compatibility of the reference dataset, which should encompass the expected cell types in the query and be generated using a compatible technology platform. These methods are particularly valuable for annotating data from technologies with limited gene panels, such as imaging-based spatial transcriptomics, where manual annotation based on marker genes becomes exceptionally challenging [31] [32].

SingleR: Correlation-Based Cell-to-Cell Annotation

SingleR (Single-cell Recognition) employs a direct correlation-based approach for unbiased cell type recognition. Its algorithm operates through several stages. First, it performs pairwise marker detection across all labels in the reference dataset. For each label, it identifies genes upregulated compared to every other label, creating a union of marker genes that provide distinguishing power. Second, it calculates the Spearman correlation between each single query cell's expression and the reference expression profiles. Each query cell is independently compared to the reference, and the label from the most correlated reference cell is initially assigned. Finally, an optional fine-tuning step iteratively reassigns labels using a subset of markers specifically discriminatory between the top candidate types, thereby improving resolution for closely related cell subsets [34] [35].

Azimuth: Integrated Reference Mapping and Transfer Learning

Azimuth implements a more complex workflow centered around reference mapping and transfer learning. Rather than correlating individual cells, Azimuth first constructs a comprehensive reference model from an annotated scRNA-seq dataset. This model incorporates multiple components: a normalized expression matrix, a dimensionality reduction (typically PCA), and a neighborhood graph that captures transcriptional relationships between cells. When a query dataset is projected onto this reference, Azimuth utilizes a weighted voting scheme based on mutual nearest neighbors to determine the most likely cell type. This approach effectively maps query cells into a stable, pre-defined classification framework, making it particularly robust for standard cell types. Azimuth also provides confidence scores and can identify cells that do not confidently match any reference type [31] [32].

Performance Comparison of Annotation Tools

Benchmarking in Spatial Transcriptomics Applications