Cell Type Annotation Validation: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Powered Solutions

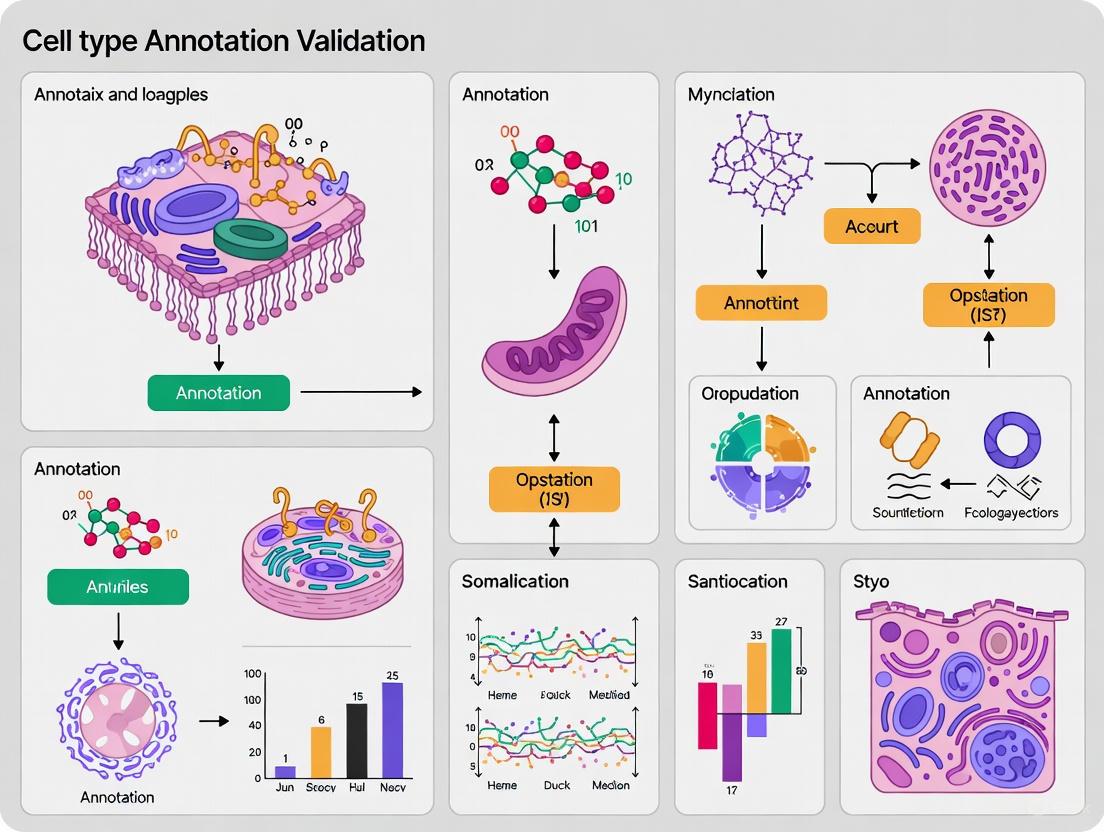

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cell type annotation validation, a critical step in single-cell RNA sequencing analysis.

Cell Type Annotation Validation: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Powered Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cell type annotation validation, a critical step in single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. It explores the transition from traditional manual annotation to advanced automated methods, including the transformative role of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Claude 3.5. We cover foundational principles, a diverse toolkit of methodologies, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous frameworks for comparative validation. Designed for researchers and bioinformaticians, this review synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to empower robust, reproducible, and accurate cell type identification, ultimately enhancing the reliability of downstream biological insights.

The What and Why of Cell Type Annotation: Core Concepts and Critical Challenges

The transition from morphological to molecular definitions of cell type identity represents a foundational shift in cellular biology. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized this process by enabling the classification of cells based on their complete transcriptomic profiles, moving beyond the limited protein markers used in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or morphological characteristics observed under a microscope [1]. This paradigm shift has uncovered unprecedented cellular heterogeneity within tissues previously considered uniform, revealing rare cell populations and continuous transitional states that challenge traditional classification systems [2]. Consequently, the computational annotation of cell types has emerged as both a critical step in scRNA-seq analysis and a significant challenge, sparking the development of numerous automated methods that vary in their underlying approaches, accuracy, and applicability [3].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the main cell type annotation methodologies, evaluating their performance against key metrics relevant to research and drug development applications. We present standardized experimental protocols and quantitative benchmarking data to help researchers select the most appropriate annotation strategy for their specific biological context, computational resources, and validation requirements. As the field progresses toward multi-modal cell identity definitions that integrate spatial, epigenetic, and proteomic data, understanding the strengths and limitations of current transcriptomics-based annotation approaches becomes increasingly crucial for ensuring reproducible and biologically meaningful results in both basic research and therapeutic discovery.

Methodological Approaches to Cell Type Annotation

Current computational methods for cell type annotation can be broadly categorized into several distinct paradigms, each with characteristic mechanisms and implementation considerations. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these primary approaches.

Table 1: Classification of Major Cell Type Annotation Methodologies

| Method Category | Underlying Mechanism | Key Examples | Typical Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Annotation | Cluster-based identification using known marker genes | Traditional expert-driven approach | Pre-defined marker gene lists, clustered scRNA-seq data |

| Reference-Based Correlation | Computes similarity to labeled reference datasets | SingleR, Azimuth, scmap, RCTD [4] | Reference scRNA-seq dataset with cell labels |

| Supervised Machine Learning | Trains classifiers on reference data | SVM, Random Forest, ACTINN [5] | Labeled training dataset, feature-selected genes |

| Deep Learning | Neural networks for pattern recognition | scTrans, scGPT, scBERT, ACTINN [6] | Large-scale training data, substantial computational resources |

| Graph Neural Networks | Models cell-cell relationships and gene networks | WCSGNet, scGraph, scPriorGraph [5] | Gene expression matrices, potentially prior biological networks |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Leverages biological knowledge embedded in language models | LICT, GPTCelltype, Cell2Sentence [7] [8] | Marker gene lists or expression patterns, API access |

Each methodological approach embodies a different strategy for addressing the fundamental challenge of cell type identification. Manual annotation represents the most traditional approach, relying on expert knowledge of established marker genes to label groups of cells after clustering [2]. While transparent and directly interpretable, this method faces challenges with subjectivity, scalability, and identification of novel cell types lacking established markers.

Reference-based methods such as SingleR and Azimuth offer a more systematic approach by comparing query datasets to extensively annotated reference atlases, calculating correlation metrics to transfer labels from the most similar reference cell types [4]. These methods benefit from the collective knowledge embedded in curated references but can struggle when query data contains cell types absent from reference collections or when technical batch effects create expression artifacts.

Deep learning approaches, including transformer-based models like scTrans and scGPT, utilize neural networks to learn complex patterns directly from gene expression data, often with minimal feature engineering [6]. These models typically demonstrate strong performance with large datasets but require substantial computational resources and careful handling of batch effects. A specialized category of deep learning, graph neural networks such as WCSGNet, further incorporates gene-gene interaction networks to model regulatory relationships, potentially capturing more biological context than expression patterns alone [5].

Most recently, large language models including GPT-4 and Claude 3 have been adapted for cell type annotation by leveraging the biological knowledge encoded in their training corpora [7] [8]. Tools like LICT (LLM-based Identifier for Cell Types) employ sophisticated multi-model integration strategies to annotate cell types based on marker gene lists, offering a reference-free alternative that can potentially identify cell populations not represented in existing scRNA-seq atlases.

Performance Benchmarking Across Platforms and Conditions

Independent benchmarking studies provide crucial empirical data for comparing the practical performance of annotation methods across diverse biological contexts. The following table synthesizes quantitative results from recent large-scale evaluations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cell Type Annotation Methods Across Experimental Conditions

| Method | Accuracy on PBMC Data | Accuracy on Low-Heterogeneity Data | Spatial Transcriptomics Performance | Scalability to Large Datasets | Handling of Novel Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SingleR | High (Reference: [4]) | Moderate | Best performing on Xenium platform [4] | High | Limited to reference content |

| Azimuth | High (Reference: [4]) | Moderate | Good performance on Xenium [4] | High | Limited to reference content |

| scTrans | High (91.4% on PBMC45k) [6] | High | Not specifically tested | Excellent (handles ~1M cells) [6] | Good generalization |

| WCSGNet | High (F1 score: 0.912) [5] | Excellent (F1 score: 0.898 on imbalanced data) [5] | Not specifically tested | High | Good with cell-specific networks |

| LLM-based (LICT) | High (90.3% match rate) [8] | Moderate (43.8-48.5% match rate) [8] | Not specifically tested | API-dependent | Excellent in theory, varies in practice |

| scmap | Moderate (Reference: [4]) | Moderate | Moderate performance on Xenium [4] | High | Limited to reference content |

| Manual Annotation | Variable (expert-dependent) | Variable (expert-dependent) | Considered gold standard but time-consuming | Low due to time constraints | Excellent in principle, requires expertise |

The benchmarking data reveals several key patterns in method performance. First, a clear trade-off emerges between reference-based and reference-free approaches. Methods like SingleR and Azimuth demonstrate strong performance on well-characterized cell types present in their reference atlases, with SingleR showing particularly strong results in spatial transcriptomics applications on Xenium platform data [4]. However, these methods inherently cannot identify novel cell types absent from their training data.

Deep learning approaches consistently achieve high accuracy across multiple tissue types, with scTrans maintaining 91.4% accuracy on PBMC45k data while efficiently scaling to datasets approaching one million cells [6]. The graph neural network method WCSGNet demonstrates particular strength in handling imbalanced datasets, achieving an F1 score of 0.898 in challenging scenarios with rare cell populations [5]. This represents a significant advantage for tissue contexts where certain cell types naturally occur at low frequencies.

LLM-based methods show promising but variable performance, with multi-model integration strategies significantly enhancing their reliability. The LICT framework increased match rates with manual annotations from 21.5% to 90.3% for PBMC data by leveraging five different LLMs (GPT-4, LLaMA-3, Claude 3, Gemini, and ERNIE) and implementing a "talk-to-machine" iterative refinement process [8]. However, performance dropped substantially for low-heterogeneity cell populations, with match rates of only 43.8-48.5% for embryonic and stromal cells, highlighting the continued challenge of annotating subtly differentiated cell states.

Spatial transcriptomics presents unique annotation challenges due to smaller gene panels and spatial autocorrelation effects. In a dedicated benchmarking study on 10x Xenium breast cancer data, reference-based methods generally showed strong performance, with SingleR producing results most closely aligned with manual pathology review while maintaining fast computation times and ease of use [4].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons between annotation methods, researchers have developed standardized evaluation protocols. The following diagram illustrates a consensus workflow for benchmarking cell type annotation performance:

This workflow begins with acquisition of publicly available scRNA-seq datasets with established cell type labels, typically from resources like the Human Cell Atlas, Tabula Muris, or Gene Expression Omnibus [3] [5]. Quality control steps filter out low-quality cells based on metrics including detected gene counts, total molecule counts, and mitochondrial gene expression percentages [3]. Reference datasets are then prepared through normalization, feature selection, and batch effect correction when integrating multiple sources.

Method execution follows standardized implementations with consistent parameter settings across tools. Performance evaluation occurs against ground truth labels established through manual annotation by domain experts, using metrics including accuracy, F1 score, adjusted Rand index, and visualization of cluster concordance. Cross-validation strategies assess generalization to novel datasets, with special attention to performance on rare cell populations and capacity to identify previously uncharacterized cell types.

LLM-Based Annotation Protocol

For large language model approaches, a specialized experimental protocol has been developed:

The LLM annotation protocol begins with clustering cells and identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each cluster. These DEGs are incorporated into structured prompts requesting cell type annotations, which are submitted to multiple LLMs in parallel [8]. The initial annotations undergo validation through a "talk-to-machine" process where the models suggest marker genes for their predicted cell types, which are then checked against expression patterns in the dataset. Annotations are considered reliable if more than four marker genes are expressed in at least 80% of cells within the cluster [8]. Failed validations trigger iterative refinement with additional DEG information until consistent annotations are achieved.

Spatial Transcriptomics Validation Protocol

For spatial transcriptomics platforms, validation incorporates orthogonal methodological approaches:

This validation approach processes serial sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples across multiple spatial transcriptomics platforms (e.g., Xenium, MERFISH, CosMx) [9]. Following platform-specific data processing and cell segmentation, reference-based annotation methods are applied alongside traditional pathology evaluation of H&E-stained sections and multiplex immunofluorescence for protein-level validation [9]. Bulk RNA-seq data from the same specimens provides expression concordance benchmarking. This multi-modal validation framework enables comprehensive assessment of annotation accuracy while accounting for platform-specific technical artifacts.

Successful cell type annotation requires both computational tools and high-quality biological data resources. The table below catalogues essential research reagents and databases referenced in method evaluations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Reference Databases for Cell Type Annotation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Application | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellMarker 2.0 | Marker Gene Database | Manual & supervised annotation | 467 human, 389 mouse cell types with markers | [3] |

| PanglaoDB | Marker Gene Database | Manual annotation | 155 human cell types with marker genes | [3] |

| Human Cell Atlas (HCA) | scRNA-seq Reference | Reference-based methods | Multi-organ datasets across 33 organs | [3] |

| Tabula Muris | scRNA-seq Reference | Cross-species validation | 20 mouse organs and tissues | [3] [5] |

| Allen Brain Atlas | Tissue-Specific Reference | Neural cell annotation | 69 neuronal cell types from human & mouse | [3] |

| 10x Genomics Xenium | Spatial Transcriptomics Platform | Spatial annotation benchmarking | Imaging-based, 100-500 gene panels | [4] [9] |

| CosMx Human Universal Panel | Spatial Transcriptomics Panel | Spatial annotation | 1,000-plex RNA panel for FFPE samples | [9] |

| MERFISH Immuno-Oncology Panel | Spatial Transcriptomics Panel | Tumor microenvironment | 500-plex RNA panel for immune cells | [9] |

These resources provide the foundational data necessary for both developing and validating cell type annotation methods. Marker gene databases like CellMarker 2.0 and PanglaoDB continue to play important roles in manual annotation and validation, despite limitations in coverage for rare or novel cell types [3]. Large-scale reference atlases including the Human Cell Atlas and Tabula Muris enable reference-based methods while facilitating cross-study comparisons. Specialized resources like the Allen Brain Atlas provide deep coverage of specific tissue contexts with particular cellular complexity.

For spatial transcriptomics applications, platform-specific gene panels represent critical reagents that directly impact annotation feasibility. Smaller gene panels (typically 100-500 genes) in platforms like Xenium and MERFISH create challenges for annotation, particularly when target genes perform poorly or when critical marker genes are absent from the panel [9]. The selection of appropriate gene panels matched to the biological context therefore represents a critical experimental design consideration preceding any computational annotation approach.

The comprehensive benchmarking of cell type annotation methods reveals a rapidly evolving landscape where methodological diversity reflects the complex challenges of cellular identity definition. No single approach currently dominates across all biological contexts, with optimal method selection depending on specific research goals, tissue types, and available computational resources. Reference-based methods like SingleR offer practical solutions for well-characterized tissues with established atlases, while deep learning approaches provide superior performance for large-scale datasets and identification of novel cell states. Emerging LLM-based strategies present intriguing opportunities for knowledge-driven annotation but require further refinement to achieve consistent performance across diverse cellular contexts.

Future methodological development will likely focus on multi-modal integration strategies that combine transcriptomic, epigenetic, proteomic, and spatial data to define cell identities more comprehensively. The systematic benchmarking frameworks and standardized validation protocols outlined in this guide provide foundational resources for these future developments, enabling rigorous evaluation of new methodologies against established benchmarks. As single-cell technologies continue to advance in scale and resolution, parallel progress in computational annotation approaches will remain essential for translating molecular measurements into biologically meaningful and therapeutically relevant cellular taxonomy.

In the rapidly advancing field of single-cell biology, accurate cell type annotation has emerged as a foundational step with profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and accelerating therapeutic development. This process of labeling individual cells based on their gene expression profiles enables researchers to decipher cellular heterogeneity, identify rare cell populations, and uncover novel disease biomarkers. The stakes for accuracy are exceptionally high; misannotation can lead researchers down unproductive therapeutic pathways, misinterpretation of disease biology, and ultimately, costly failures in drug development pipelines. As single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies generate increasingly massive datasets, the limitations of both manual expert annotation and early computational methods have become apparent. Manual approaches, while benefiting from expert knowledge, are inherently subjective and time-consuming, whereas many automated tools demonstrate limited generalizability due to their dependence on specific reference datasets [10].

The emergence of sophisticated artificial intelligence approaches, particularly those leveraging large language models (LLMs) and specialized deep learning architectures, promises to transform this landscape. These new methods aim to provide scalable, reproducible, and objective frameworks for cell type identification while minimizing the biases inherent in previous approaches. This comparison guide provides an objective evaluation of two cutting-edge cell type annotation tools—LICT, which employs a multi-LLM strategy, and scTrans, which utilizes a specialized transformer architecture—to help researchers select the most appropriate methodology for their specific research context, particularly as it relates to disease research and drug development applications.

Tool Comparison: LICT vs. scTrans

Performance Benchmarking Across Diverse Biological Contexts

The accuracy and reliability of cell type annotation tools vary significantly across different biological contexts, including normal physiology, developmental stages, and disease states. The following table summarizes the comparative performance of LICT and scTrans across multiple datasets and conditions:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of LICT and scTrans Across Diverse Biological Contexts

| Dataset Type | Specific Dataset | LICT Performance | scTrans Performance | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Heterogeneity | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Mismatch rate reduced to 9.7% (from 21.5% with GPTCelltype) [10] | Validated on PBMC45k, PBMC160k, and scBloodNL datasets [6] | Both tools perform well on highly heterogeneous cell populations |

| High Heterogeneity | Gastric Cancer | Mismatch rate reduced to 8.3% (from 11.1% with GPTCelltype) [10] | Strong performance on mouse brain and pancreas datasets [6] | LICT demonstrates significant improvement over previous LLM approaches |

| Low Heterogeneity | Human Embryos | Match rate increased to 48.5% [10] | Information not available in search results | LICT shows dramatic improvement but significant challenges remain |

| Low Heterogeneity | Stromal Cells (Mouse) | Match rate of 43.8% [10] | Accurate annotation on T cell and dendritic cell development datasets [6] | Both tools address low-heterogeneity challenges through different strategies |

| Large-Scale Atlas | Mouse Cell Atlas (31 tissues) | Information not available in search results | Efficient annotation of nearly million cells with limited computational resources [6] | scTrans demonstrates superior scalability for very large datasets |

| Novel Datasets | Cross-dataset validation | Credibility assessment via marker gene expression [10] | Strong generalization capabilities and high-quality latent representations [6] | Both tools designed specifically for generalizability to novel data |

Technical Approaches and Architectural Comparison

The fundamental architectural differences between LICT and scTrans lead to distinct strengths and limitations for specific research scenarios:

Table 2: Technical Architecture and Implementation Comparison

| Feature | LICT (LLM-Based Approach) | scTrans (Specialized Transformer) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Multi-LLM integration with "talk-to-machine" strategy [10] | Sparse attention mechanism focusing on non-zero genes [6] |

| Input Data Processing | Standardized prompts incorporating top marker genes [10] | Direct processing of all non-zero genes without HVG pre-filtering [6] |

| Reference Dependence | Reference-independent; leverages embedded biological knowledge [11] [10] | Pre-trained on large atlases (e.g., Mouse Cell Atlas) then fine-tuned [6] |

| Computational Requirements | Moderate (multiple API calls to LLMs) [10] | High efficiency; optimized for limited computational resources [6] |

| Key Innovation | Objective credibility evaluation through marker gene validation [10] | Minimized information loss while reducing dimensionality [6] |

| Interpretability | "Talk-to-machine" provides transparent validation process [10] | Attention weights identify functionally critical genes [6] |

| Batch Effect Mitigation | Not explicitly addressed | Strong robustness to batch effects through architecture design [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

LICT Methodology: Multi-Model Integration and Validation

The LICT framework employs a sophisticated multi-stage approach that combines the strengths of multiple large language models with iterative validation:

Model Selection and Initial Annotation: LICT begins by evaluating multiple LLMs (including GPT-4, LLaMA-3, Claude 3, Gemini, and ERNIE 4.0) on a benchmark PBMC dataset using standardized prompts containing the top ten marker genes for each cell subset. The system selects the best-performing models for integration [10].

Multi-Model Integration Strategy: Instead of conventional majority voting, LICT employs a complementary model approach that selects the best-performing results from five different LLMs. This strategy leverages the diverse strengths of each model to improve annotation accuracy and consistency, particularly for challenging low-heterogeneity cell populations [10].

"Talk-to-Machine" Iterative Validation: This human-computer interaction process represents LICT's core innovation for improving annotation precision:

- Marker Gene Retrieval: The LLM is queried to provide representative marker genes for each predicted cell type based on initial annotations.

- Expression Pattern Evaluation: The expression of these marker genes is assessed within corresponding clusters in the input dataset.

- Validation Criteria: An annotation is considered valid if more than four marker genes are expressed in at least 80% of cells within the cluster.

- Iterative Feedback: For failed validations, a structured feedback prompt containing expression validation results and additional differentially expressed genes is used to re-query the LLM for revised annotations [10].

Objective Credibility Evaluation: The final stage implements a framework to distinguish methodological discrepancies from intrinsic dataset limitations by assessing annotation credibility through marker gene expression patterns, providing researchers with reliability metrics for downstream analysis [10].

LICT Multi-Stage Annotation Workflow

scTrans Methodology: Sparse Attention Architecture

The scTrans framework employs a specialized transformer architecture designed specifically to address the challenges of high-dimensional, sparse single-cell data:

Pre-processing and Input Representation: Unlike methods that rely on highly variable gene (HVG) selection, scTrans processes all non-zero genes in the dataset. Each gene is mapped to a high-dimensional vector space, preserving information that might be lost through conventional filtering approaches [6].

Sparse Attention Mechanism: The core innovation of scTrans is its use of sparse attention within a transformer architecture. This mechanism focuses computational resources on non-zero gene expressions, effectively reducing dimensionality and computational complexity while minimizing information loss. This approach allows the model to maintain high performance even with limited computational resources [6].

Two-Stage Training Pipeline:

- Pre-training Phase: scTrans employs unsupervised contrastive learning on large-scale unlabeled data (e.g., Mouse Cell Atlas) to learn generalizable representations of cellular states without requiring extensive labeled datasets.

- Fine-tuning Phase: The pre-trained model is subsequently fine-tuned on labeled data specific to the target application, enabling adaptation to specific tissues, species, or experimental conditions [6].

Latent Representation Generation: Beyond cell type annotation, scTrans generates high-quality latent representations that are useful for additional downstream analyses, including clustering, trajectory inference, and visualization. These representations demonstrate strong robustness to batch effects and technical variations [6].

scTrans Two-Stage Training Architecture

Implications for Disease Research and Drug Development

Impact on Disease Mechanism Elucidation

Accurate cell type annotation serves as the critical foundation for understanding disease mechanisms at cellular resolution. In complex diseases like Alzheimer's disease, where drug development has faced significant challenges, single-cell technologies offer new avenues for target identification [12]. The ability to accurately identify and characterize rare cell populations—such as disease-specific microglial states in neurodegeneration or treatment-resistant clones in cancer—enables researchers to develop more targeted therapeutic approaches. LICT's objective credibility assessment is particularly valuable in this context, as it helps researchers distinguish between genuine biological phenomena and potential annotation artifacts that could misdirect research efforts [10].

The application of these tools extends to early disease detection through identification of subtle cellular alterations that precede clinical symptoms. In neurodegenerative disease research, biomarkers such as phosphorylated tau are being validated for early Alzheimer's pathology detection [13]. Accurate annotation of cell types expressing these early markers could significantly improve diagnostic timeframes and enable preventive interventions. scTrans's capability to maintain consistent performance across novel datasets makes it particularly suitable for multi-center studies that combine data from different institutions and platforms [6].

Accelerating Therapeutic Development Pipelines

The drug development landscape for complex diseases is undergoing transformation through technologies that depend on precise cellular characterization:

Table 3: Therapeutic Approaches Dependent on Accurate Cell Annotation

| Therapeutic Approach | Dependency on Accurate Annotation | Relevance to Annotation Tools |

|---|---|---|

| CAR-T Therapy | Requires precise identification of target cell populations and characterization of tumor microenvironment [13] | scTrans's ability to process large datasets enables comprehensive tumor ecosystem mapping |

| PROTACs | Understanding cell-type specific protein degradation pathways and potential off-target effects [13] | LICT's multi-model approach can identify cell-type specific E3 ligase expression patterns |

| Radiopharmaceutical Conjugates | Accurate quantification of target antigen expression across different cell types [13] | Both tools provide robust annotation of cell types expressing therapeutic targets |

| Microbiome-Targeted Therapies | Characterization of host cell responses to microbial interventions [13] | LICT's credibility assessment validates annotations in novel therapeutic contexts |

| CRISPR Therapies | Assessment of cell-type specific editing efficiency and off-target effects [13] | scTrans's latent representations help monitor cellular responses to gene editing |

The high failure rates in Alzheimer's disease drug development, where only drugs in late Phase 1 or later stages have a chance of approval by 2025, underscore the need for better target validation [12]. Accurate cell type annotation can improve this process by ensuring that therapeutic targets are appropriately expressed in relevant cell types and that animal models accurately reflect human cellular heterogeneity. Furthermore, the emergence of AI-powered clinical trial simulations and digital twin technologies depends on high-quality cellular data to create accurate in silico representations of disease processes [13].

Successful implementation of advanced cell type annotation methods requires specific computational resources and reference datasets:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Annotation Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Mouse Cell Atlas, Tabula Muris, Human Cell Atlas | Benchmarking and validation of annotation performance [6] |

| Computational Frameworks | Python, TensorFlow/PyTorch, R Single-Cell Ecosystem | Implementation of annotation algorithms and downstream analysis [10] [6] |

| Benchmarking Tools | scRNA-seq data from PBMCs, human embryos, gastric cancer, stromal cells | Performance validation across diverse biological contexts [10] |

| Validation Resources | Marker gene databases, curated cell type signatures | Objective credibility assessment and annotation verification [10] |

| Hardware Infrastructure | GPU clusters, high-memory computing nodes | Handling large-scale datasets and computationally intensive algorithms [6] |

The comparative analysis of LICT and scTrans reveals distinct strengths that recommend each tool for different research scenarios within disease research and drug development. LICT's multi-LLM approach offers significant advantages for researchers seeking to maximize annotation accuracy through an iterative, validated process that incorporates biological knowledge through marker gene validation. Its reference-independent nature makes it particularly valuable for exploratory studies involving novel cell types or poorly characterized disease states. The objective credibility assessment provides researchers with confidence metrics that are invaluable for prioritizing downstream experiments.

Conversely, scTrans's specialized architecture excels in large-scale applications where computational efficiency and batch effect mitigation are primary concerns. Its ability to process nearly a million cells with limited computational resources, while maintaining strong generalization across novel datasets, makes it ideal for consortium-level projects and industrial drug development pipelines that integrate data across multiple sources and platforms.

The strategic selection between these approaches should be guided by specific research objectives, computational resources, and the biological context under investigation. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve and generate increasingly complex datasets, the accurate annotation of cell types will remain a cornerstone of biomedical discovery, serving as the critical link between molecular measurements and biological insight with profound implications for understanding human disease and developing effective therapeutics.

The advent of single-cell and spatial genomics technologies has revolutionized our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity within complex biological systems. These platforms enable researchers to move beyond bulk tissue analysis, providing unprecedented resolution to characterize individual cells and their spatial context. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of three prominent technological approaches: droplet-based 10x Genomics Chromium, full-length plate-based Smart-seq2, and emerging spatial transcriptomics platforms. Understanding the technical capabilities, advantages, and limitations of each platform is essential for researchers designing experiments, particularly in the context of cell type annotation validation—a critical step in accurately interpreting single-cell and spatial data. Each platform embodies distinct methodological trade-offs between throughput, sensitivity, resolution, and cost, making informed platform selection fundamental to research success in drug development and basic biological research.

Platform Methodologies and Technical Specifications

The 10x Genomics Chromium system employs a droplet-based methodology that uses microfluidic partitioning to encapsulate individual cells in oil droplets with barcoded beads. This approach allows for simultaneous processing of thousands to millions of cells, making it ideal for large-scale profiling studies. The platform primarily captures the 3' or 5' ends of transcripts, providing digital counting of mRNA molecules through unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) that help account for amplification biases [14]. In contrast, Smart-seq2 is a plate-based, full-length RNA sequencing method that provides complete transcript coverage. This protocol utilizes optimized reverse transcription with template-switching oligonucleotides (TSOs) and locked nucleic acid (LNA) technology to achieve high sensitivity and detect more genes per cell, including alternatively spliced isoforms, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and allelic variants [15]. Spatial transcriptomics platforms represent a different paradigm, focusing on retaining the geographical context of gene expression. Sequencing-based approaches like 10x Visium capture whole transcriptome data from tissue sections at spot-level resolution (each containing multiple cells), while imaging-based platforms like 10x Xenium achieve subcellular resolution but are limited to targeted gene panels of several hundred genes [4] [16].

Comprehensive Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of these platforms based on direct comparative studies:

Table 1: Direct Performance Comparison of Single-Cell and Spatial Genomics Platforms

| Performance Metric | 10x Genomics Chromium | Smart-seq2 | 10x Visium (Spatial) | 10x Xenium (Spatial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (Cells) | High (thousands to millions) | Low to medium (96-384 per plate) | Spot-based (5,000 spots per slide) | High (millions of cells per slide) |

| Genes Detected per Cell | ~1,000-5,000 (depending on cell type) | ~4,000-9,000 (higher sensitivity) | ~3,000-5,000 per spot (whole transcriptome) | Targeted (~100-500 gene panel) |

| Transcript Coverage | 3' or 5' focused (UMI-based) | Full-length | Whole transcriptome (3' biased) | Targeted transcripts only |

| Spatial Resolution | No native spatial information | No native spatial information | Multi-cellular spots (55-100 μm) | Single-cell/subcellular |

| Detection of Splice Variants | Limited | Excellent | Limited | Limited |

| Detection of Non-coding RNAs | Higher proportion of lncRNAs [14] | Lower proportion of lncRNAs | Not well characterized | Dependent on panel design |

| Mitochondrial Gene Capture | Lower proportion | Higher proportion [14] | Standard | Dependent on panel design |

| Data Sparsity (Dropout Rate) | Higher, especially for low-expression genes [14] | Lower | Moderate | Low for targeted genes |

| Single-Nucleotide Variant Detection | Limited | Excellent [15] | Limited | Limited |

| Cell Type Annotation Method | Cluster-based with markers | Cluster-based with markers | Spot deconvolution required | Reference-based or marker-based |

Beyond these core platforms, methodological evolution continues with newer protocols like Smart-seq3, which incorporates UMIs while maintaining full-length coverage, and FLASH-seq, which offers a significantly faster one-day workflow with improved sensitivity and reproducibility compared to Smart-seq2 [15]. FLASH-seq's more processive reverse transcriptase provides better full-length coverage of longer transcripts and yields eight times more cDNA than Smart-seq protocols with the same number of PCR cycles, making it particularly suitable for cells with low RNA content [15].

Experimental Design and Data Analysis Considerations

Platform Selection for Specific Research Goals

The choice of sequencing platform should align directly with the primary research question. For comprehensive cell atlas construction and identification of rare cell populations, 10x Genomics Chromium provides the necessary throughput and cost-effectiveness to profile large numbers of cells. Studies have demonstrated that 10x-based data can detect rare cell types more effectively due to its ability to cover a large number of cells [14]. When the research goal involves alternative splicing analysis, detection of allelic expression, or comprehensive transcriptional characterization at the single-cell level, full-length methods like Smart-seq2 or FLASH-seq offer superior performance. Smart-seq2 detects more genes per cell, especially low-abundance transcripts and alternatively spliced isoforms, and its composite data more closely resembles bulk RNA-seq data [14]. For investigations requiring anatomical context, such as studying tissue microenvironments, cellular neighborhoods, and spatial localization of cell types, spatial transcriptomics platforms are indispensable. Each spatial technology presents trade-offs; 10x Visium provides whole transcriptome profiling but at multi-cellular resolution, while imaging-based platforms like 10x Xenium offer single-cell resolution but are restricted to predefined gene panels [4] [16].

Cell Type Annotation Strategies Across Platforms

Cell type annotation represents a critical analytical step that varies significantly across platforms. For 10x Genomics and Smart-seq2 data, annotation typically involves unsupervised clustering followed by marker-based identification using known cell type-specific genes. For spatial transcriptomics data, additional computational challenges emerge. Sequencing-based spatial data like 10x Visium requires deconvolution methods to infer cell type compositions within each spot, with top-performing tools including Cell2location, SpatialDWLS (in Giotto), and RCTD (in spacexr) [17] [18]. For imaging-based spatial data like 10x Xenium, reference-based annotation methods have shown excellent performance, with benchmarking studies identifying SingleR as the top-performing tool—being fast, accurate, and producing results closely matching manual annotation [4] [16]. Other effective methods for imaging-based spatial data include Azimuth, RCTD, scPred, and scmapCell, though their performance varies in accuracy and computational requirements [16].

Table 2: Optimal Cell Type Annotation Methods for Different Data Types

| Data Type | Recommended Annotation Methods | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Seurat clustering + marker identification | Cluster stability and marker specificity are crucial |

| Smart-seq2 | Seurat/SCANPY clustering + marker identification | Higher gene detection improves annotation resolution |

| 10x Visium (Spatial) | Cell2location, SpatialDWLS, RCTD | Account for spot composition and potential cell type mixtures |

| 10x Xenium (Spatial) | SingleR, Azimuth, scPred | Reference quality significantly impacts annotation accuracy |

Experimental Design and Protocol Considerations

When designing single-cell RNA sequencing experiments, researchers must consider several practical aspects. For plate-based methods like Smart-seq2, the protocol involves multiple steps including reverse transcription, template switching, and preamplification, typically requiring two days to process a 96-well plate [15]. Newer methods like FLASH-seq have streamlined this to a one-day workflow (approximately seven hours) by integrating reverse transcription and cDNA amplification into a single step [15]. For droplet-based methods like 10x Genomics Chromium, the wet-lab workflow is faster, but substantial computational resources are required for data processing. Spatial transcriptomics experiments require careful tissue preparation, optimization of permeabilization time, and morphological assessment. For imaging-based spatial technologies, panel design is critical and should be informed by prior single-cell RNA sequencing data or literature-based marker genes to ensure comprehensive cell type detection.

Integrated Analysis and Methodological Benchmarking

Integration of Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics Data

Integration methods that combine single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial transcriptomics data have emerged as powerful approaches to overcome the limitations of individual technologies. These integration methods serve two primary purposes: predicting the spatial distribution of undetected transcripts and deconvoluting cell type compositions in spots. Benchmarking studies evaluating 16 different integration methods on 45 paired datasets have identified Tangram, gimVI, and SpaGE as the top-performing methods for predicting spatial RNA distribution, while Cell2location, SpatialDWLS, and RCTD excel at spot deconvolution [17] [18]. The performance of these methods varies in their handling of data sparsity, accuracy of cell type mapping, and computational resource requirements. For instance, Seurat demonstrates advantages in computational efficiency for predicting spatial RNA distribution, while Tangram and Seurat show better performance for deconvolution tasks in terms of resource consumption [17].

Platform-Specific Data Characteristics and Analytical Implications

Each platform generates data with distinct characteristics that influence downstream analytical approaches. 10x Genomics data typically exhibits higher sparsity (dropout rates), particularly for genes with lower expression levels, which can impact the detection of subtle transcriptional differences [14]. Approximately 10-30% of all detected transcripts in 10x data are from non-coding genes, with long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) accounting for a higher proportion compared to Smart-seq2 [14]. Smart-seq2 data demonstrates higher sensitivity for gene detection and lower data sparsity but captures a higher proportion of mitochondrial genes, which can sometimes reflect cell stress or vary by cell type [14]. Spatial transcriptomics data introduces additional analytical considerations, including spatial autocorrelation, region-specific expression patterns, and technical artifacts related to tissue preparation. For sequencing-based spatial data, the multi-cellular nature of each spot requires specialized deconvolution approaches, while imaging-based spatial data, despite its single-cell resolution, faces challenges of limited gene panels that may not capture all cell types equally.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of single-cell and spatial genomics technologies relies on specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table outlines key solutions required for different stages of experimental workflow and data analysis:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell and Spatial Genomics

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium Next GEM Kits, SMART-Seq Single Cell Kit (Takara) | Generate barcoded sequencing libraries from single cells |

| Spatial Gene Expression Kits | 10x Visium Spatial Gene Expression, Xenium Gene Expression Kit | Preserve spatial information during library preparation |

| Cell Type Annotation Tools | SingleR, Azimuth, scPred, scmap | Automated cell type annotation using reference datasets |

| Spatial Deconvolution Tools | Cell2location, SpatialDWLS, RCTD | Infer cell type proportions in multi-cellular spots |

| Data Integration Tools | Tangram, gimVI, SpaGE | Integrate single-cell and spatial data for enhanced analysis |

| Reference Datasets | Human Cell Atlas, Mouse Cell Atlas, Tabula Sapiens | High-quality reference for cell type annotation |

| Analysis Platforms | Seurat, Scanpy, Giotto | Comprehensive analysis environment for single-cell and spatial data |

The rapidly evolving landscape of single-cell and spatial genomics technologies offers researchers multiple powerful options for exploring cellular heterogeneity. 10x Genomics Chromium provides unparalleled throughput for large-scale cell atlas projects, Smart-seq2 and its successors offer superior sensitivity for detailed molecular characterization of individual cells, and spatial transcriptomics platforms enable the crucial integration of geographical context. The optimal choice depends heavily on the specific research questions, with considerations including target cell numbers, required gene detection sensitivity, need for isoform-level information, and importance of spatial localization. As these technologies continue to mature, we anticipate further convergence of single-cell and spatial approaches, improved computational methods for data integration, and enhanced multiplexing capabilities that will provide even more comprehensive views of cellular biology. For cell type annotation validation research, a combined approach utilizing high-throughput screening followed by targeted deep characterization often provides the most robust validation strategy, leveraging the complementary strengths of these diverse technological platforms.

The Inherent Challenges of Manual Annotation

Cell type annotation is a foundational step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, crucial for elucidating cellular composition and function within complex tissues [19]. For years, the predominant approach has been manual annotation, a process where human experts assign cell type identities to cell clusters by comparing cluster-specific marker genes with prior knowledge of canonical cell type markers [20] [2]. While this method benefits from deep expert knowledge, it is fraught with significant challenges that create a central bottleneck in single-cell research pipelines.

Manual annotation is inherently labor-intensive and time-consuming, requiring the meticulous collection of canonical marker genes and careful comparison against differential gene expression data for each cell cluster [20]. This process is not only slow but also highly subjective, as the annotations are heavily dependent on the individual annotator's experience and prior knowledge [19]. This subjectivity introduces irreproducibility, as different research groups—or even the same researchers at different times—may assign different labels to identical cell populations based on similar data [21]. The problem is compounded by the fact that manual annotations often lack standardization, frequently not being based on standardized ontologies of cell labels, which further hinders reproducibility across different experiments and research groups [21].

Another critical limitation is the dependency on well-defined marker genes. This approach struggles when unique markers do not exist for specific cell types, which occurs frequently, forcing annotators to rely on combinations of markers or expression thresholds that further complicate the process and reduce objectivity [2]. Furthermore, as single-cell technologies advance, enabling the profiling of millions of cells and the discovery of increasingly subtle cell states, the scalability of manual annotation becomes a severe limitation, preventing fast and reproducible analysis of large-scale datasets [21].

Automated Cell Type Annotation: A Comparative Analysis

To address the limitations of manual annotation, numerous computational methods have been developed, broadly falling into three categories: marker-based, correlation-based, and model-based approaches [22] [23]. The performance of these methods varies significantly based on the dataset complexity, annotation level, and biological context. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of prominent annotation tools as established in benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Automated Cell Type Annotation Methods

| Method | Type | Reported Accuracy (Key Datasets) | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM [21] [24] | Model-based | Top performer in intra- and inter-dataset evaluations [21] | High accuracy & scalability; low unclassified cell rate [21] | Performance can decrease with complex, overlapping classes [21] |

| ScType [25] | Marker-based | 98.6% (6 datasets, 72/73 types) [25] | Ultra-fast; uses positive/negative marker combinations [25] | Dependent on marker database coverage [25] |

| scBERT [24] | Model-based | Top performer among deep learning methods [24] | Leverages deep learning on large datasets [23] | "Black-box" nature limits interpretability [23] |

| SingleR [21] | Correlation-based | Good performance in benchmark studies [21] | Does not require training a classifier [21] | Struggles with batch effects between reference/query [23] |

| scCATCH [22] [25] | Marker-based | High accuracy in multiple tissues [25] | Tissue-specific taxonomy & evidence-based scoring [22] | May be less accurate for rare or novel cell types [25] |

| GPT-4/GPTCelltype [20] [19] | LLM-based | >75% concordance with manual annotations [20] | No reference data needed; handles various tissues [20] | Performance can drop for low-heterogeneity cells [19] |

Recent evaluations, including one that tested 18 classification methods on an experimentally labeled immune cell-subtype dataset to avoid computational biases, confirmed that SVM, scBERT, and scDeepSort are among the best-performing supervised methods [24]. For marker-based approaches, ScType has demonstrated exceptional accuracy (98.6%) across six human and mouse tissue datasets, successfully re-annotating several cell types that were incorrectly labeled in original studies [25].

A groundbreaking development is the application of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4. Studies have shown that GPT-4 can automatically and accurately annotate cell types using marker gene information, exhibiting strong concordance with manual annotations across hundreds of tissue and cell types in both normal and cancer samples [20]. However, its performance, like that of other LLMs, can diminish when annotating less heterogeneous datasets [19].

Table 2: Performance in Annotating Different Cell Type Categories

| Cell Category | Example Cell Types | Annotation Challenge | Method Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Types | T cells, B cells, Macrophages [20] | Lower | High accuracy across most methods [20] |

| Cell Subtypes | CD4+ memory T, Naive B, DC subsets [20] | Higher | GPT-4 has significantly higher "fully match" for major types [20] |

| Low-Heterogeneity | Stromal cells, Embryonic cells [19] | Higher | All LLMs show significant discrepancy vs. manual annotation [19] |

| Malignant Cells | Cancer cells from tumors [20] | Context-dependent | GPT-4 identified them in colon/lung cancer but failed in BCL [20] |

Advanced Architectures and Integrated Solutions

To overcome the limitations of individual methods, researchers are developing more sophisticated architectures that integrate multiple data types and strategies.

Multi-Model and Interactive LLM Strategies

The tool LICT (Large Language Model-based Identifier for Cell Types) tackles LLM limitations through a multi-pronged approach. Its multi-model integration strategy leverages multiple LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Claude 3, Gemini) and selects the best-performing result, significantly reducing the mismatch rate compared to using a single model like GPTCelltype [19]. Furthermore, its "talk-to-machine" strategy creates an iterative feedback loop where the LLM's initial predictions are validated against the dataset's gene expression patterns. If validation fails, the LLM is queried again with the validation results and additional differentially expressed genes, leading to improved annotation accuracy for both high- and low-heterogeneity datasets [19].

Pathway-Informed Graph-Based Models

scMCGraph represents a significant architectural advance by integrating gene expression with pathway activity to construct a consensus cell-cell graph [23]. The model constructs multiple pathway-specific views of cellular relationships using various pathway databases. These views are then fused into a single consensus graph that captures a more robust representation of cellular interactions, which is subsequently used for cell type annotation. This approach has demonstrated exceptional robustness and accuracy in cross-platform, cross-time, and cross-sample evaluations, showing that introducing pathway information significantly enhances the learning of cell-cell graphs and improves predictive performance [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of this integrated, pathway-informed approach:

Diagram 1: Workflow of a pathway-informed graph-based model (e.g., scMCGraph) for cell type annotation.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Annotation Methods

Robust benchmarking is essential for evaluating the performance of various cell type annotation methods. The following protocols are commonly employed in the field, as detailed in the search results.

Intra-Dataset and Inter-Dataset Validation

Benchmarking typically involves two primary experimental setups [21]. Intra-dataset validation employs 5-fold cross-validation within a single dataset. The dataset is divided into five folds in a stratified manner to ensure each cell population is equally represented in each fold. The classifier is trained on four folds and predicts on the fifth, repeating until all folds have served as the test set. This provides an ideal scenario to evaluate classification performance without the confounding factor of technical variations [21] [24]. Inter-dataset validation is a more realistic and challenging setup where a classifier is trained on a reference dataset (e.g., an atlas) and then applied to predict cell identities in a completely separate query dataset. This tests the method's ability to handle technical and biological variations across studies and is a key indicator of practical utility [21].

Performance Metrics and Agreement Scoring

To quantify performance, supervised methods are typically evaluated using metrics such as Accuracy and the F1-score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall) [21] [24]. For unsupervised clustering, the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) is often used to measure the similarity between the computational clustering and the ground truth labels [24]. When comparing against manual annotations, a structured agreement score is frequently applied. A pair of manual and automatic annotations is classified as [20]:

- "Fully match": Same annotation term or Cell Ontology name (Score = 1).

- "Partially match": Same or subordinate broad cell type name (e.g., fibroblast vs. stromal cell) but different specific annotations (Score = 0.5).

- "Mismatch": Different broad cell type names (Score = 0).

The average agreement score across a dataset provides a standardized measure of concordance with manual labels [20].

Successful cell type annotation relies on a suite of computational tools and reference resources. The table below details key components of the modern annotation toolkit.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Type Annotation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CellMarker / CellMatch [22] [25] | Marker Database | Curated collection of cell-type-specific marker genes. | Provides prior knowledge for marker-based methods (ScType, scCATCH). |

| Cell Ontology (CL) [20] [26] | Ontology | Standardized vocabulary for cell types. | Enables consistent naming and reconciliation of annotations. |

| ACT (Annotation of Cell Types) [26] | Web Server | Knowledge-based annotation using hierarchically organized marker maps. | Allows input of upregulated genes for enrichment-based cell type assignment. |

| Azimuth [20] [22] | Reference-based Tool | Maps query data to a single-cell reference atlas. | Provides cell type predictions based on Seurat's reference datasets. |

| ScType Database [25] | Marker Database | Comprehensive database of positive and negative marker combinations. | Enables fully-automated, specific cell type identification. |

| Uber-anatomy Ontology [26] | Ontology | Standardized hierarchy for tissue names. | Helps standardize tissue context for marker genes. |

| GPTCelltype / LICT [20] [19] | Software Package | Interfaces with LLMs (GPT-4) for annotation. | Allows for reference-free annotation using marker gene lists. |

The field of cell type annotation is rapidly evolving beyond its manual origins. While manual annotation provides a valuable benchmark, its laborious, subjective, and non-scalable nature makes it a significant bottleneck in the era of large-scale single-cell genomics. Automated methods—including marker-based, correlation-based, and sophisticated model-based approaches—offer scalable, reproducible, and increasingly accurate alternatives. Benchmarking studies consistently highlight top performers like SVM, ScType, and scBERT, while emerging strategies such as multi-model LLM integration and pathway-informed graph models push the boundaries of accuracy, especially for complex or low-heterogeneity cell populations. The future of cell type annotation lies in leveraging these powerful, standardized computational tools to ensure reproducibility and accelerate biological discovery, while still incorporating expert knowledge for validation and the interpretation of novel cell states.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to probe cellular heterogeneity, yet key computational challenges impede progress in cell type annotation validation research. Data sparsity, where 80% or more of gene expression values are zero, complicates accurate cell-type identification [27] [28]. Batch effects introduce technical variations that can confound biological interpretations [29] [30], while the "long-tail" distribution of rare cell types remains difficult to identify and validate [3] [8]. This guide objectively compares computational strategies addressing these interconnected challenges, providing researchers with methodological frameworks and benchmarking data to enhance annotation reliability across diverse experimental contexts.

Cell type annotation serves as the critical foundation for interpreting single-cell RNA sequencing data, enabling researchers to decipher cellular composition, identify novel populations, and understand disease mechanisms [3] [2]. Despite technological advances, persistent computational challenges affect annotation accuracy and reliability. Data sparsity in scRNA-seq manifests as an excess of zero values, with approximately 80% of gene expression measurements reporting zero counts due to both biological absence of expression and technical "dropout" events where expressed genes fail to be detected [27] [28]. This sparsity distances between cells and complicates cell-type identification.

Batch effects represent systematic technical variations introduced when cells are processed in different laboratories, at different times, or using different sequencing platforms [29] [30]. These effects can profoundly confound biological interpretations, potentially leading to false discoveries of novel cell populations when technical artifacts are misinterpreted as biological signals [27]. The long-tail problem refers to the challenge of accurately identifying rare cell types that appear infrequently in datasets but often hold significant biological importance [3]. As annotation methods increasingly operate in "open-world" contexts where unknown cell types may be present, the ability to distinguish rare populations becomes increasingly critical for comprehensive tissue characterization [3].

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods

Methodologies for Addressing Data Sparsity

Data sparsity presents dual challenges of computational efficiency and information preservation. Traditional approaches employ dimensionality reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) or highly variable gene (HVG) selection to mitigate the curse of dimensionality [6]. However, these methods inevitably discard potentially biologically relevant information. Emerging deep learning frameworks address this limitation through specialized architectures designed to handle sparse inputs while maximizing information retention.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods Addressing Data Sparsity

| Method | Approach | Sparsity Handling | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scTrans | Transformer with sparse attention | Utilizes all non-zero genes with sparse attention | Minimizes information loss; strong generalization; provides interpretable attention weights | Computational complexity with extremely large datasets [6] |

| HVG-Based Methods | Selection of highly variable genes | Reduces dimensionality by focusing on high-variance genes | Computational efficiency; reduces noise | Potential loss of biologically relevant genes; batch-dependent HVG selection [6] |

| ZINB-WaVE | Zero-inflated negative binomial model | Statistical modeling of zero inflation | Accounts for technical zeros; provides observation weights | Performance deteriorates with very low sequencing depths [29] |

| scGPT | Generative pre-trained transformer | Whole-transcriptome modeling | Captures complex gene relationships; multiple downstream tasks | High computational resource requirements [6] |

The recently developed scTrans framework employs sparse attention mechanisms to efficiently process all non-zero gene expressions without requiring preliminary gene selection, thereby minimizing information loss while maintaining computational feasibility [6]. Benchmarking experiments across 31 tissues in the Mouse Cell Atlas demonstrated that scTrans achieves accurate annotation even with limited labeled cells and shows strong generalization to novel datasets [6]. When evaluating sparsity-handling methods, researchers should consider whether their experimental context requires whole-transcriptome analysis or whether targeted gene approaches suffice for their specific biological questions.

Batch Effect Correction Strategies

Batch effect correction methods aim to remove technical variations while preserving biological signals. These algorithms employ diverse mathematical frameworks, including mutual nearest neighbors (MNN), canonical correlation analysis (CCA), and deep learning approaches [31] [28] [30]. The performance of these methods varies significantly depending on batch effect strength, sequencing depth, and data sparsity [29].

Table 2: Benchmarking of Batch Effect Correction Methods

| Method | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Performance Notes | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fastMNN | Mutual nearest neighbors | Fast PCA-based implementation; identifies MNN pairs across batches | Superior performance for large datasets; preserves biological heterogeneity | Large-scale integrations; datasets with shared cell types [31] [30] |

| Harmony | Iterative clustering | Iteratively clusters cells while removing batch effects | Efficient integration; good visualization results | Datasets with clear cluster structure; routine integrations [28] |

| Seurat v3 | CCA + MNN | Projects data into correlated subspace; uses CCA and MNN | Robust to composition differences; established track record | Complex integrations with varying cell type compositions [28] |

| Scanorama | MNN in reduced space | Similarity-weighted approach using MNNs in dimensional space | High performance on complex data; returns corrected matrices | Diverse datasets with multiple batch effects [28] |

| scVI | Variational autoencoder | Probabilistic modeling of scRNA-seq data | Effective for complex batch structures; enables multiple downstream tasks | Deep learning pipelines; complex experimental designs [29] |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes | Adapts bulk RNA-seq correction method | Established methodology; familiar to many researchers | Smaller datasets; when traditional statistics preferred [29] |

A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluating 46 differential expression workflows revealed that batch effect strength and sequencing depth significantly impact correction performance [29]. For large batch effects, covariate modeling approaches (including batch as a covariate in statistical models) consistently outperformed methods that use pre-corrected data [29]. At very low sequencing depths (average of 4-10 non-zero counts per cell), traditional methods like Wilcoxon tests performed robustly, while zero-inflation models showed deteriorated performance [29].

Figure 1: Batch effect correction workflow with key validation metrics.

Approaches to the Long-Tail Problem of Rare Cell Types

The long-tail distribution of cell types presents particular challenges for annotation, as rare populations are often underrepresented in reference datasets yet may hold significant biological importance [3]. Traditional supervised learning approaches struggle with imbalanced class distributions, frequently misclassifying or overlooking rare cell types. Innovative computational strategies are emerging to address this fundamental limitation.

Multi-Model Integration and LLM-Based Approaches The recently developed LICT (Large Language Model-based Identifier for Cell Types) framework employs a multi-model integration strategy that leverages complementary strengths of multiple large language models, including GPT-4, Claude 3, and Gemini [8]. This approach demonstrates particular value for rare cell type identification, increasing match rates for low-heterogeneity datasets from approximately 30% with single models to 48.5% through model integration [8]. The system incorporates an objective credibility evaluation strategy that assesses annotation reliability based on marker gene expression patterns, providing researchers with confidence metrics for rare cell identifications.

Deep Learning and Open-World Recognition Advanced deep learning architectures are increasingly incorporating open-world recognition principles, enabling annotation systems to identify when cells do not match known reference types [3]. Transformer-based models like scTrans demonstrate enhanced capability to generalize to novel datasets and identify rare populations through their attention mechanisms that can highlight distinctive gene expression patterns even in sparse data [6]. These approaches show promise for addressing the long-tail problem by reducing dependence on pre-defined reference atlases.

Table 3: Performance Comparison on Rare Cell Type Identification

| Method | Rare Cell Type Detection Strategy | Validation Approach | Reported Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LICT | Multi-LLM integration with credibility assessment | Marker gene expression validation | 48.5% match rate on embryo data (vs. 39.4% for best single model) | Still >50% inconsistency for low-heterogeneity cells [8] |

| scTrans | Sparse attention on all non-zero genes | Cross-dataset generalization | Strong performance on novel datasets; high-quality latent representations | Computational demands for extremely large datasets [6] |

| Open-World Framework | Dynamic clustering with continual learning | Novel cell type recognition | Theoretical foundation for unknown type identification | Still in early development [3] |

| Covariate Modeling | Batch-aware statistical testing | Differential expression benchmarking | Improved rare cell DE detection in large batch effects | Benefit diminishes at very low sequencing depths [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Benchmarking Framework for Annotation Methods

Robust validation of annotation methods requires standardized benchmarking frameworks. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach derived from recent large-scale method comparisons:

Dataset Curation: Assemble diverse scRNA-seq datasets spanning multiple tissues, species, and experimental protocols. Include datasets with known ground truth annotations, such as the Mouse Cell Atlas [6] or human PBMC datasets [8].

Data Preprocessing: Apply consistent quality control metrics, including filters for mitochondrial gene percentage, minimum gene counts, and cell viability markers [31] [2]. Normalize data using standard methods such as library size normalization with log transformation.

Method Application: Implement annotation algorithms using standardized parameters. For reference-based methods, ensure consistent reference database usage. For unsupervised methods, maintain consistent clustering parameters.

Performance Quantification: Evaluate using multiple metrics including:

- Accuracy: Proportion of correctly annotated cells compared to ground truth

- F-score: Balance between precision and recall, particularly important for rare cell types

- Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR): Especially relevant for imbalanced cell type distributions [29]

- Consistency: Agreement with manual expert annotations [8]

Robustness Assessment: Test method performance across varying sequencing depths, batch effect strengths, and different levels of data sparsity [29].

Batch Effect Correction Evaluation Protocol

Rigorous evaluation of batch effect correction requires both visual and quantitative assessments:

Visual Inspection: Generate UMAP/t-SNE visualizations before and after correction, coloring cells by batch and cell type [31] [28]. Effective correction should show mixing of batches while maintaining distinct cell type separation.

Quantitative Metrics:

Biological Conservation Assessment:

- Differential expression testing between cell types pre- and post-correction

- Marker gene expression preservation analysis

- Cluster-specific marker identification post-integration

Credibility Assessment for Rare Cell Types

The LICT framework introduces a structured approach for evaluating annotation reliability, particularly valuable for rare cell types [8]:

Marker Gene Retrieval: For each predicted cell type, query the system to generate representative marker genes.

Expression Pattern Evaluation: Analyze expression of these marker genes within corresponding cell clusters in the input dataset.

Credibility Thresholding: Classify annotations as reliable if more than four marker genes are expressed in at least 80% of cells within the cluster.

Iterative Refinement: For annotations failing credibility thresholds, incorporate additional differentially expressed genes and re-query the system in an interactive "talk-to-machine" approach [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Critical computational tools and resources for addressing scRNA-seq challenges:

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for scRNA-seq Challenges

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CellMarker 2.0 | Marker gene database | Curated marker genes for human and mouse cell types | Manual annotation validation; rare cell type identification [3] |

| PanglaoDB | Marker gene database | Community-curated cell type markers with tissue specificity | Cross-tissue annotation; novel cell type discovery [3] |

| batchelor | R package | Batch correction using fastMNN and other algorithms | Integrating datasets with composition differences [31] |

| Seurat | R toolkit | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis including integration | End-to-end analysis pipelines; CCA-based integration [28] |

| Harmony | Algorithm | Iterative batch effect correction | Rapid integration of multiple datasets [28] |

| SCTrans | Python package | Transformer-based annotation with sparse attention | Handling extreme sparsity; rare cell type identification [6] |

| LICT | LLM-based tool | Multi-model cell type identification with credibility assessment | Objective reliability assessment; rare cell validation [8] |

| Scanorama | Python tool | Efficient batch correction using MNNs | Large-scale data integration; complex batch structures [28] |

Figure 2: Method selection guide based on primary data challenges.

Computational challenges of data sparsity, batch effects, and rare cell types represent interconnected obstacles in single-cell genomics that require coordinated methodological advances. Current benchmarking indicates that method performance is highly context-dependent, with no single approach optimally addressing all challenges. Sparsity-optimized transformers like scTrans show promise for minimizing information loss, while mutual nearest neighbor methods consistently demonstrate robust batch correction across diverse experimental conditions. For the persistent long-tail problem, emerging strategies combining multi-model integration with objective credibility assessments offer measurable improvements in rare cell type identification.

Future methodological development should prioritize open-world frameworks capable of recognizing novel cell types outside reference atlases, dynamic clustering approaches that adapt to evolving cellular taxonomies, and continual learning systems that accumulate knowledge across experiments [3]. Integration of multi-omics data at single-cell resolution presents another promising avenue for addressing current limitations in annotation reliability [3]. As computational strategies mature, rigorous benchmarking against standardized datasets and validation metrics remains essential for translating technical advances into biological insights with diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

The Annotation Toolkit: From Reference-Based Methods to AI and LLMs

Cell type annotation is a critical, foundational step in the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (data. Accurate annotation enables researchers to decipher cellular heterogeneity, understand cell-cell interactions, and identify rare cell populations, which is indispensable for both basic research and drug development. Reference-based annotation methods have emerged as powerful alternatives to manual marker-gene approaches, offering increased throughput, reproducibility, and reduced expert bias. Among these, SingleR, Seurat (and its integrated Azimuth tool), and other specialized algorithms have become traditional workhorses in the field. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and experimental protocols of these key tools, providing a structured overview for scientists engaged in cell type annotation validation research.

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Comparison

Independent benchmarking studies provide crucial insights into the practical performance of annotation tools. A 2025 systematic evaluation on 10x Xenium imaging-based spatial transcriptomics data offers a direct comparison of several reference-based methods against manual annotation [4].

Table 1: Performance Benchmark of Cell Type Annotation Tools on Xenium Data

| Tool | Reported Performance | Speed | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| SingleR | Best performing; results closely matched manual annotation [4]. | Fast [4]. | Accurate, fast, and easy to use [4]. |

| Azimuth | Evaluated in benchmark [4]. | Information Missing | Web app for easy use; integrated with Seurat [32] [33]. |

| RCTD | Evaluated in benchmark [4]. | Information Missing | Developed for sequencing-based spatial data [4]. |

| scPred | Evaluated in benchmark [4]. | Information Missing | Uses a classification algorithm for prediction [4]. |

| scmapCell | Evaluated in benchmark [4]. | Information Missing | Projects cells based on similarity [4]. |

Beyond tools specifically designed for annotation, the Seurat framework itself provides a versatile platform for data integration and analysis. Its IntegrateLayers function supports multiple integration methods (CCA, RPCA, Harmony, FastMNN, scVI), which is a critical pre-processing step that can improve downstream annotation accuracy by effectively merging datasets from different batches or experiments [34].

Performance can also vary with data type. A 2025 benchmarking study on machine learning models highlighted that while ensemble methods like XGBoost can achieve high accuracy (>95%) on single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data, performance can notably decline when the same models are applied to single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) data, underscoring the impact of transcriptome isolation techniques [35].

Experimental Protocols for Tool Evaluation

The reliability of performance benchmarks hinges on rigorous and reproducible experimental methodologies. The following summarizes key protocols from cited studies.

Benchmarking Protocol for Spatial Transcriptomics Data