Combating Cell Culture Microbial Contamination: From Foundational Knowledge to Cutting-Edge Detection Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing microbial contamination in cell culture.

Combating Cell Culture Microbial Contamination: From Foundational Knowledge to Cutting-Edge Detection Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing microbial contamination in cell culture. It covers the foundational knowledge of common contaminants like bacteria, mycoplasma, and viruses, explores traditional and novel detection methodologies including machine learning-aided UV spectroscopy and VOC analysis, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for both research and GMP environments. Furthermore, it discusses validation requirements and compares the efficacy of various detection techniques, concluding with future directions for ensuring the integrity and safety of cell-based products and research.

Understanding the Invisible Enemy: A Guide to Common Cell Culture Contaminants

Within the broader scope of research on microbial contamination in cell culture, bacterial contamination represents one of the most common and immediately detectable challenges. It can surreptitiously affect data quality, compromise experimental results, and lead to costly setbacks [1] [2]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the ability to rapidly identify bacterial contamination through visual cues like turbidity and pH shifts is a fundamental skill for maintaining culture integrity. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting support for recognizing and addressing these specific contamination indicators.

FAQ: Turbidity and pH Shifts in Cell Culture

Q1: What are the primary visual signs of bacterial contamination in my cell culture? The most immediate signs are increased turbidity (a cloudy or hazy appearance) and a sharp drop in the pH of the medium, often indicated by a color change to yellow [1] [3] [4]. This occurs because bacteria metabolize nutrients and produce acidic byproducts. Under a low-power microscope, you may observe tiny, shimmering granules moving between your cells [4].

Q2: Why does the pH of my culture medium drop suddenly? A sudden pH drop is a metabolic signature of bacterial contamination. Bacteria consume nutrients in the medium, such as glucose, and produce acidic waste products like lactic acid. Most cell culture media contain phenol red, a pH indicator that turns yellow under acidic conditions, providing a visible alert [3] [4].

Q3: I see turbidity, but my cells still look okay. Should I be concerned? Yes, you should treat this as a confirmed contamination. Bacterial growth can be incredibly rapid. Even if your cells appear unaffected initially, the bacteria will eventually outcompete them for nutrients, release toxic waste, and lead to cell death. It is recommended to discard the culture promptly to prevent spread [5] [4].

Q4: How can I distinguish bacterial contamination from other types, like yeast or fungi? While all can cause turbidity, the specifics differ. Yeast appears as individual ovoid or spherical particles that may bud off smaller particles, and pH may only increase with heavy contamination [5] [4]. Fungi present as thin, wispy filamentous mycelia or clumps of spores [5] [4]. Bacteria, in contrast, typically cause a rapid pH drop and under the microscope appear as tiny, moving rods or cocci [1] [4].

Q5: What are the most common sources of bacterial contamination? Contamination can originate from multiple sources, including lab personnel, unfiltered air, non-sterile reagents or media, humidified incubators, and unsterilized equipment like biosafety cabinets [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Data and Detection

Characteristic Signs of Common Contaminants

The table below summarizes the key characteristics to help differentiate between major types of biological contaminants.

Table 1: Identification Guide for Common Cell Culture Contaminants

| Contaminant | Visual Culture Appearance | Microscopic Observation (100–400x) | Typical pH Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Cloudy (turbid) medium; possibly a thin film on the surface [4] | Tiny, shimmering granules; rods or cocci may be observed [5] [4] | Sharp drop (acidic) [1] [5] |

| Yeast | Cloudy medium, especially in advanced stages [4] | Round or ovoid particles that bud off smaller particles [5] [4] | Stable initially, then may increase with heavy infection [5] [4] |

| Fungi/Mold | Cloudy medium; floating clumps [2] | Thin filamentous mycelia; sometimes clumps of spores [5] [4] | Changes sometimes; can be stable [5] |

| Mycoplasma | No turbidity; no obvious visual signs [3] [5] | Not detectable by routine microscopy; requires DNA staining (e.g., Hoechst) or PCR [1] [3] | No consistent change [5] |

A robust contamination control program employs a variety of detection methods, chosen based on the suspected contaminant.

Table 2: Overview of Microbial Contamination Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Primary Use | Brief Protocol Overview | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual & Microscopic Inspection | Routine monitoring for bacteria, yeast, fungi [2] | Daily observation of culture clarity and color. Examine under phase-contrast microscope for foreign particles or structures [3]. | Rapid, low-cost, first line of defense [6] |

| Microbial Culture | Detecting cultivable bacteria, yeast, and fungi [1] | Inoculate a sample of the cell culture into nutrient broth or agar and incubate for 1-3 days to observe for microbial growth [1]. | Confirms viability of contaminants |

| PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) | Detecting mycoplasma, viruses, and specific pathogens [1] [2] | Extract nucleic acids from the cell culture or supernatant and use target-specific primers to amplify unique microbial DNA/RNA sequences [1] [3]. | Highly sensitive and specific; detects non-cultivable organisms [1] |

| DNA Staining (e.g., Hoechst) | Detecting mycoplasma and viral plaques [1] [3] | Stain fixed cells with a fluorescent DNA-binding dye (e.g., Hoechst 33258) and examine under a fluorescence microscope for particulate or filamentous staining outside the cell nuclei [3] [5]. | Visual confirmation of mycoplasma DNA [5] |

| ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) | Detecting viral antigens or endotoxins [2] | Use antibodies immobilized on a plate to capture specific viral antigens or endotoxins from a sample, followed by detection with an enzyme-linked antibody and a colorimetric substrate [2]. | Can screen for specific viruses and toxins |

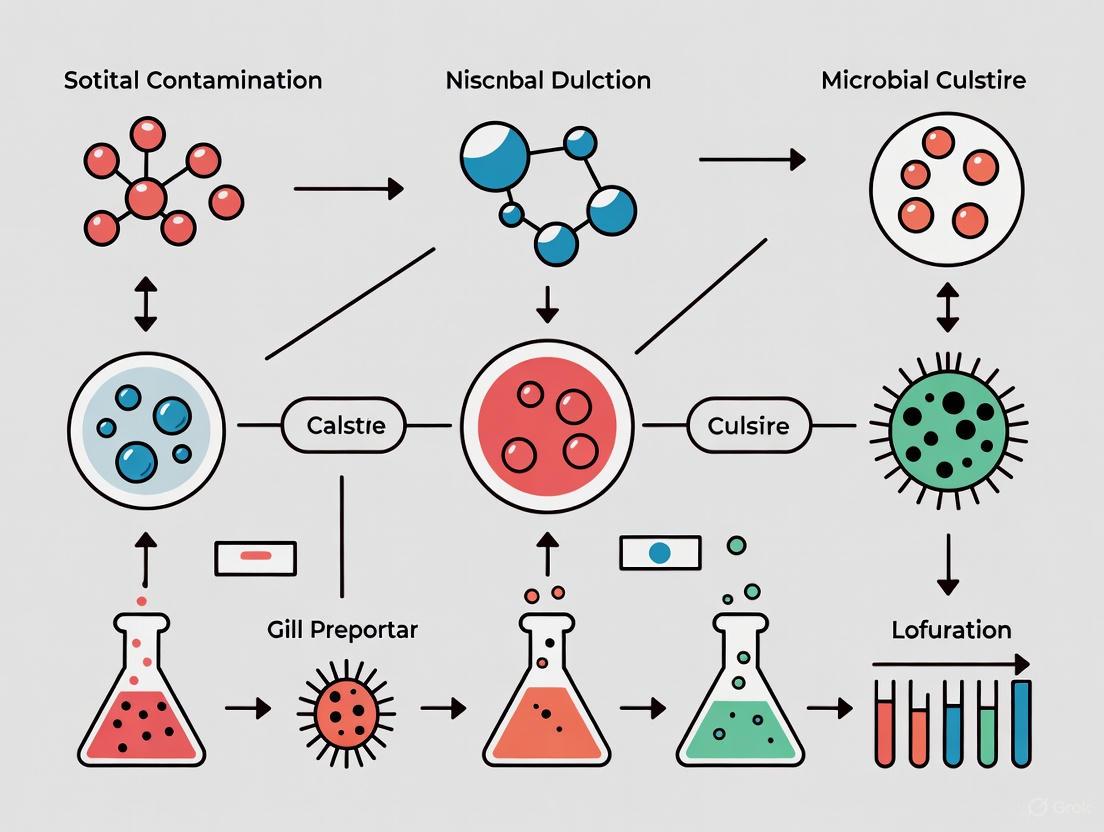

Visual Workflow: From Detection to Action

The following diagram outlines the logical decision-making process for addressing suspected bacterial contamination.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials critical for both preventing contamination and conducting detection experiments.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol | Surface and glove disinfection in the BSC and lab [1] [7] | Effective concentration for microbial kill; evaporates quickly without residue [7]. |

| Phenol Red Medium | Visual pH indicator for culture health [3] | Yellow color indicates acidic shift (potential bacterial growth); pink indicates alkaline shift [3] [4]. |

| Antibiotics/Antimycotics | Suppression of microbial growth (e.g., Penicillin/Streptomycin) [1] [4] | Use strategically, not routinely, to avoid masking low-level contamination and breeding resistance [2] [4]. |

| Sterile Filtration Units (0.22 µm) | Sterilization of heat-sensitive solutions [1] | Standard pore size for removing bacteria; not effective for mycoplasma (<0.1 µm required) [1] [3]. |

| Hoechst 33258 Stain | Fluorescent detection of mycoplasma DNA [1] [5] | Requires fluorescence microscopy; reveals mycoplasma as particulate or filamentous staining outside cell nuclei [3] [5]. |

| PCR Kits for Mycoplasma | Highly sensitive detection of mycoplasma DNA [1] [3] | More sensitive than staining; available as a service from many cell banks and testing companies [3] [6]. |

Proactive Prevention Strategy

Preventing contamination is far more efficient than dealing with its consequences. A multi-layered defense strategy is most effective.

The most critical element in combating all cell culture contamination, including bacterial, remains consistent and meticulous aseptic technique [1]. Those techniques—combined with the strategic use of antibiotics, proper cell repository management, and a robust contamination monitoring program—form the cornerstone of reliable and reproducible cell culture research [1].

Mycoplasma contamination represents one of the most significant yet frequently overlooked problems in cell culture laboratories worldwide. These stealthy contaminants are the smallest and simplest self-replicating prokaryotes, lacking a cell wall and possessing a minimal genome of approximately 580-1358 kb [8]. Their small size (0.3-0.8 μm in diameter) allows them to readily pass through standard 0.22 μm filters used for sterilizing cell culture media [9]. Unlike bacterial contamination that often causes turbidity in media, mycoplasma contamination typically doesn't trigger visible changes, meaning most contaminated cultures show no obvious signs of infection [10] [11]. This invisible nature, combined with their resistance to common antibiotics like penicillin and streptomycin, makes them a persistent threat to research integrity [9] [12].

The incidence of mycoplasma contamination in continuous cell cultures is alarmingly high, estimated to affect 15-35% of cell lines, with primary cell cultures exhibiting at least a 1% contamination rate [12]. More than 200 mycoplasma species have been identified, but only about 20 species of human, bovine, and porcine origin typically contaminate cell cultures [9] [12]. A mere eight species account for approximately 95% of all contamination incidents: M. arginini (bovine), M. fermentans (human), M. hominis (human), M. hyorhinis (porcine), M. orale (human), M. pirum (human), M. salivarium (human), and Acholeplasma laidlawii (bovine) [12].

Detection and Diagnosis: Identifying the Contaminant

Why Routine Detection is Challenging

Mycoplasma contamination rarely produces the dramatic visual changes associated with other microbial contaminants. However, careful observation can reveal subtle indicators that should trigger formal testing:

- Reduced cell proliferation rates due to competition for nutrients with mycoplasmas [10]

- Cell aggregation and morphological changes in previously uniform cultures [10]

- Poor transfection efficiencies in cells that previously showed high transfection rates [10]

- Interference with biochemical assays including MTT tetrazolium dye-based cytotoxicity assays [13]

Available Detection Methods

Multiple methods are available for mycoplasma detection, each with advantages and limitations. The table below summarizes the most commonly used techniques:

Table 1: Comparison of Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Time to Result | Sensitivity | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological Culture | Growth on selective agar/broth media | 4-5 weeks [12] | Moderate | Detects only cultivable mycoplasmas [8] | Long incubation period [8] |

| DNA Staining (DAPI/Hoechst) | Fluorescent dyes bind to mycoplasma DNA | 1-3 days [8] | Moderate to High | Visual confirmation possible | Requires indicator cells [8] |

| PCR-Based Methods | Amplification of mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences | Several hours [9] [14] | High (~10 CFU/mL) [14] | Rapid and sensitive | Detects DNA from non-viable organisms |

| Enzymatic Labeling | Incorporation of modified nucleotides into mycoplasma DNA | Several hours [8] | High | Does not intensely stain nuclear DNA [8] | Newer, less established method |

| RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a | Isothermal amplification with CRISPR-based detection | <1 hour [15] | Very High (0.1-10 copies/μL) [15] | Extreme sensitivity and speed | Requires specialized reagents |

Recommended PCR Protocol for Detection

For most laboratories, PCR-based methods offer the optimal balance of speed, sensitivity, and practicality. The following protocol adapted from current research provides reliable detection:

Sample Preparation:

- Transfer 200 μL of cell culture supernatant (after at least 12 hours of cell culture) to a sterile 1.5 mL tube

- Incubate at 95°C for 5 minutes to release DNA

- Samples can be stored at 2-8°C for up to one week or at -20°C for several months [9]

PCR Reaction Setup:

- Use universal primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene:

- Forward: 5'-GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGTATCCCT-3'

- Reverse: 5'-TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC-3' [9]

- Employ a touchdown PCR protocol to increase sensitivity and specificity

- Include appropriate positive and negative controls

Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes

- 35-40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 55-65°C for 30 seconds (temperature varies by protocol)

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

Result Analysis:

- Analyze PCR products by gel electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose-TAE gel

- Visualize with appropriate DNA staining

- Expected product size varies by species but typically ranges from 500-1000 bp

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My cell culture isn't showing visible contamination, but cell growth has slowed significantly and experiments are yielding inconsistent results. Could this be mycoplasma contamination?

A: Yes, these are classic signs of mycoplasma contamination. Unlike bacterial contamination that often causes turbidity or pH changes, mycoplasma contamination manifests through more subtle effects including reduced cell proliferation rates, changes in cellular metabolism, and inconsistent experimental results [10] [11]. We recommend implementing routine PCR-based testing every 2-4 weeks or whenever introducing new cell lines.

Q: I've confirmed mycoplasma contamination in my prized cell line that would be extremely difficult to replace. Is eradication possible?

A: While complete elimination is challenging, several approaches can be attempted for irreplaceable cell lines:

- Antibiotic treatments specifically targeting mycoplasma (different from standard penicillin/streptomycin)

- Mycoplasma removal agents available commercially

- Passage through mice for certain cell types

- Limiting dilution cloning to isolate uncontaminated subpopulations

However, prevention remains vastly superior to treatment, as eradication success rates vary and may alter cell characteristics [16] [11].

Q: How does mycoplasma contamination affect specialized techniques like ATAC-seq and RNA-seq?

A: Mycoplasma contamination significantly compromises epigenetic and transcriptomic studies:

- ATAC-seq results are particularly vulnerable as the method employs Tn5 transposase to detect chromatin accessibility on a genome-wide scale, which is substantially affected by mycoplasma DNA [9]

- RNA-seq samples can be partially protected through poly(A) enrichment of RNA, but contamination still poses significant risks [9]

- Gene expression profiles become unreliable as mycoplasma infection can dysregulate hundreds of host genes [9]

Q: What are the most common sources of mycoplasma contamination in research laboratories?

A: Primary contamination sources include:

- Contaminated cell lines received from other laboratories (most common)

- Laboratory personnel through poor aseptic technique

- Contaminated reagents of animal origin, particularly serum

- Contaminated equipment shared between cell lines

- Environmental sources in laboratories with inadequate airflow control [11] [12]

Mycoplasma Interference with Cellular Metabolism and Signaling

Mycoplasma contamination exerts profound effects on cellular functions through multiple mechanisms, primarily by competing for essential nutrients and altering metabolic pathways. The diagram below illustrates key metabolic pathways disrupted by mycoplasma contamination:

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC/MS)-based metabolomics studies have demonstrated that mycoplasma contamination induces significant metabolic changes in infected cells. Research using PANC-1 human pancreatic carcinoma cells identified 23 significantly altered metabolites involved in three primary pathways [13]:

Table 2: Metabolic Pathways Affected by Mycoplasma Contamination

| Affected Pathway | Specific Alterations | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Arginine Metabolism | Depletion of arginine, accumulation of ornithine and urea | Disruption of nitric oxide synthesis, polyamine metabolism, and protein synthesis [13] |

| Purine Metabolism | Changes in adenosine, inosine, hypoxanthine, and adenine levels | Alteration of DNA/RNA synthesis, energy transfer, and signaling pathways [13] |

| Energy Metabolism | Disruption of TCA cycle intermediates (succinate, fumarate, malate) | Compromised mitochondrial function and cellular energy production [13] |

| Choline Metabolism | Depletion of choline and phosphocholine | Impacts membrane integrity and cell signaling [13] |

These metabolic disruptions explain many observed phenotypic effects of mycoplasma contamination, including:

- Chromosomal aberrations and disruption of nucleic acid synthesis [12]

- Changes in membrane antigenicity and receptor expression [12]

- Inhibition of cell proliferation and metabolic activity [12]

- Altered response to chemotherapeutic agents in cancer cell lines [11]

- Modulation of immune cell functions including cytokine production and lymphocyte activation [8]

Prevention Protocols: Building a Contamination Defense System

Preventing mycoplasma contamination requires a systematic, multi-layered approach. The following evidence-based practices significantly reduce contamination risk:

Laboratory Practice Controls

- Strict aseptic technique: Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves and lab coat. Change lab coats at least weekly [9]

- Biosafety cabinet maintenance: Keep culture hoods clean and well-organized, ensuring unobstructed airflow. Disinfect all items with 75% alcohol before placing in hood [9]

- Proper container management: Ensure adequate covering of plates and bottles at all times [9]

- Spill management: Clean spills immediately to prevent aerosol contamination [9]

Cell Culture Management

- Quarantine all new cell lines: Isolate untested cell lines in a designated incubator until confirmed mycoplasma-free [9] [11]

- Implement cell banking: Adhere to the seed stock principle to ensure availability of fresh, uncontaminated stocks [12]

- Regular incubator maintenance: Disinfect incubators regularly with bleach, change water in humidifying pans weekly [9]

- Avoid antibiotic overuse: Recognize that standard antibiotics don't prevent mycoplasma contamination and may mask problems [12]

Quality Control Measures

- Routine testing schedule: Test cell lines every 2-4 weeks using PCR-based methods

- Reagent qualification: Use only mycoplasma-free media, sera, and reagents from qualified suppliers [12]

- Personnel training: Ensure all laboratory staff receive proper training in aseptic technique and contamination prevention

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Contamination Management

Table 3: Key Reagents for Mycoplasma Detection and Prevention

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Detection Kits | MycoSEQ Mycoplasma Detection Kits [14] | qPCR-based detection with TaqMan chemistry | Meets regulatory sensitivity requirements (10 CFU/mL) [14] |

| Culture Media | PPLO broth [8] | Selective cultivation of mycoplasmas | Requires supplementation with serum and specific nutrients [8] |

| DNA Staining Dyes | DAPI, Hoechst 33258 [8] [12] | Fluorescent staining of mycoplasma DNA | Often requires indicator cell lines for sufficient sensitivity [8] |

| Specialized Media Supplements | Horse serum, yeast extract, L-arginine [8] | Support mycoplasma growth in culture media | Essential for microbiological culture methods [8] |

| Antibiotic/Antimycotic Solutions | Zell Shield [9] | Prevention of bacterial and fungal contamination | Note: Most standard antibiotics are ineffective against mycoplasma [9] |

| Rapid Test Kits | MycoStrip [9] | Quick detection of mycoplasma contamination | Useful for regular screening without specialized equipment |

| Mycoplasma Removal Agents | Specific antibiotics targeting mycoplasma | Elimination of contamination from valuable cultures | Success rates vary; may alter cell characteristics |

Mycoplasma contamination remains a persistent, invisible threat that compromises cellular functions and jeopardizes research validity. The stealthy nature of these contaminants, combined with their profound effects on cellular metabolism, gene expression, and experimental outcomes, necessitates rigorous detection and prevention protocols. By implementing regular testing schedules, adhering to strict aseptic techniques, quarantining new cell lines, and maintaining proper laboratory hygiene, researchers can protect their valuable cell cultures and ensure the reliability of their scientific data. Remember: when it comes to mycoplasma contamination, vigilance is not optional—it's essential for research integrity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: How do I identify a fungal or yeast contamination in my cell culture?

Problem: Suspected microbial contamination causing cloudy media or unusual pH shifts in cell culture.

Solution: A combination of macroscopic observation, microscopic analysis, and advanced detection techniques can confirm and identify the contaminant.

Step-by-Step Identification Protocol:

Macroscopic Observation: Visually inspect the culture medium.

- Turbidity: Look for an increase in turbidity (cloudiness) in the medium. This is a common sign of microbial growth [17] [4].

- pH Changes: Note any changes in the color of the medium if it contains phenol red as a pH indicator. Bacterial contamination often causes a rapid yellow shift (acidification), while yeast contamination may show little to no color change in the initial stages, with the pH usually increasing only in advanced stages [17] [4].

Microscopic Analysis:

- Use an inverted phase-contrast microscope for examination [17].

- Magnification: Observe at 100x to 400x magnification [17].

- Visual Identification:

- Yeasts: Appear as single, ovoid, or spherical particles. You may observe them budding off smaller particles. They can exist as single cells or in chains [17] [4].

- Molds: Appear as thin, filamentous structures (hyphae). These may appear as wispy filaments or denser clumps of spores (mycelia) under the microscope [4].

Advanced and Rapid Detection Methods: For faster, more sensitive, or automated detection, consider these emerging technologies:

- UV Absorbance Spectroscopy with Machine Learning: A novel, label-free method that uses ultraviolet light absorbance patterns of cell culture fluids and machine learning to provide a definitive contamination assessment within 30 minutes [18].

- Electronic Nose (e-nose): A sensor-based device that can detect and identify fungal contamination by analyzing the profile of volatile organic compounds (MVOCs) released by microbes in the headspace of a sample [19].

- Microfluidic Systems: Integrated systems capable of enriching and detecting specific airborne fungal spores (e.g., Aspergillus niger) through immunofluorescence analysis within 2-3 hours [20].

Interpretation of Results: The table below summarizes the key characteristics to differentiate common contaminants.

Table 1: Identifying Common Biological Contaminants in Cell Culture

| Contaminant Type | Macroscopic Signs | Microscopic Morphology | Typical pH Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast [17] [4] | Cloudy (turbid) medium | Ovoid or spherical particles, often budding | Stable initially, increases later |

| Mold [4] | Cloudy medium, sometimes with floating films | Thin, wispy filaments (hyphae) | Stable initially, increases later |

| Bacteria [4] | Cloudy medium, thin surface film | Tiny, moving granules (rods, cocci) | Rapid decrease (acidification) |

Guide 2: What are the best practices to prevent airborne fungal and yeast contamination?

Problem: Recurring contamination incidents are compromising experimental results and cell line integrity.

Solution: Implement a rigorous aseptic technique protocol and maintain a clean laboratory environment.

Prevention and Contamination Control Protocol:

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and Aseptic Zone:

Proper Use of Cell Culture Hood:

- Wipe down all surfaces of the hood with 70% ethanol or IMS before and after every use [21].

- Do not block the front and rear grilles to ensure proper airflow [21].

- Work with all materials and containers within a clean, uncluttered workspace inside the hood, not near the edges [21].

- Use UV light to sterilize the hood when not in use [21].

Laboratory and Equipment Hygiene:

- Incubators: Clean and disinfect incubators regularly according to the manufacturer's protocol. Change the water in humidifying trays frequently and add a microbiostatic agent [21].

- Water Baths: Change the water in water baths used for warming media regularly and treat it to prevent microbial growth [21].

- Reagents and Labware: Use only sterile, certified reagents and materials. Aliquot reagents to avoid contaminating entire stocks. Sterilize labware via autoclaving where appropriate [21].

Antibiotic and Antimycotic Use:

- Note: Antibiotics and antimycotics should not be used routinely as a substitute for good aseptic technique. Their continuous use can lead to resistant strains and mask cryptic contaminants like mycoplasma [4].

- If used, they should be for short-term applications only, and antibiotic-free cultures should be maintained in parallel as a control [4].

Diagram: Contamination Prevention and Response Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My cell culture looks cloudy, but I see no bacteria or yeast under the microscope. What could it be? A1: Cloudy culture in the absence of visible bacteria or yeast can indicate contamination with mycoplasma [4]. These are very small bacteria that lack a cell wall and are extremely difficult to detect with standard microscopy. You should test your culture using specialized methods such as PCR, immunostaining, or commercial mycoplasma detection kits.

Q2: I've identified a contamination. Can I save my irreplaceable cell line with antibiotics? A2: It is possible to attempt decontamination, but success is not guaranteed and carries risks. The process involves [4]:

- Isolating the contaminated culture.

- Determining the toxicity level of a high-concentration antibiotic/antimycotic to your specific cell line.

- Treating the culture for 2-3 passages at a concentration just below the toxic level.

- Culturing the cells in antibiotic-free medium for several passages to verify the contamination has been eliminated. However, the use of antibiotics can induce cellular stress and alter cell physiology, potentially compromising future experimental results. Cryopreserving a clean stock is always preferable to decontamination.

Q3: What are the common sources of fungal and yeast contamination in a lab? A3: These contaminants are ubiquitous in the environment. Common sources include [19] [21]:

- Air: Unfiltered air handling systems or drafts can introduce spores.

- Personnel: Skin, hair, and clothing.

- Surfaces: Non-sterile workbenches, incubators, and water baths.

- Reagents: Non-sterile media, sera, or other supplements.

Q4: Are there any rapid, modern methods for detecting contamination beyond the microscope? A4: Yes, the field is advancing rapidly. Two promising methods are:

- Machine Learning with UV Spectroscopy: This method analyzes the UV light "fingerprint" of the cell culture fluid and can provide a yes/no contamination result in under 30 minutes, enabling early detection during manufacturing [18].

- Electronic Nose (e-nose): This device uses an array of gas sensors to detect volatile organic compounds (MVOCs) produced by microbes, allowing for early identification of fungal genus without lengthy culture steps [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Contamination Management

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phase-Contrast Microscope [17] | Visualization of live cells and contaminants (yeast, molds) without staining. | Essential for routine monitoring. Magnification of 100x-400x is sufficient for initial detection. |

| 70% Ethanol / IMS [21] | Surface and equipment decontamination within the cell culture hood and laboratory. | The water content in 70% solution increases efficacy against bacteria and viruses. |

| Antibiotic/Antimycotic Solutions [4] | Suppression of microbial growth in cell cultures. | Use as a last resort, not routinely. Determine optimal (non-toxic) concentration empirically for your cell line. |

| UV Absorbance Spectrometer [18] | Core component of a rapid, machine learning-based detection system for contamination. | Enables label-free, non-invasive, and real-time analysis of culture sterility. |

| Electronic Nose (MOS Gas Sensor Array) [19] | Early detection and identification of fungal contamination by analyzing MVOC profiles. | Useful for environmental monitoring of labs and incubators, as well as sample analysis. |

| Microfluidic Immunoassay System [20] | Rapid, high-throughput detection and enrichment of specific airborne pathogenic spores. | Provides targeted analysis; whole process can be completed in 2-3 hours. |

Viral contamination represents a unique and formidable challenge in cell culture. Unlike bacterial or fungal contamination, which often present visible signs, viral contaminants are silent, intracellular threats that can compromise research integrity and product safety without obvious warning [22] [23]. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers navigate these hidden risks.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Detection and Identification

Q: How can I detect a viral contaminant that isn't causing visible cell death? Many viruses, particularly retroviruses, establish chronic infections without cytopathic effects [11]. Detection requires specific methods beyond routine microscopy:

- PCR assays: Effective for known viruses like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [24]

- Broad-spectrum methods: In vitro virus assays using multiple detector cell lines can identify contaminants through cytopathic effects, hemadsorption, or immunofluorescence [25]

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS): Powerful for detecting unknown adventitious agents without prior selection of nucleic acids [25]

Q: What are the most common sources of viral contamination in cell culture? Contamination typically originates from three primary sources [22]:

- Original tissues/tumor material: Primary cultures may harbor latent viruses from the donor organism [26]

- Biological reagents: Animal-derived components like fetal bovine serum and trypsin are frequent contamination vectors [25] [26]

- Cross-contamination: Between cell lines or through laboratory personnel [27]

Q: Which viruses should I be most concerned about in my cell cultures? Risk profiles vary by cell type, but prevalent contaminants include:

- Minute Virus of Mice (MVM): Particularly problematic in CHO cell cultures, resistant to inactivation [25]

- Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV): Ubiquitous in human populations, potentially latent in human-derived cell lines [24]

- Retroviruses: Can silently integrate as proviruses into host genomes [22]

- Ovine Herpesvirus 2 (OvHV-2): Broad species tropism, concerning for laboratories using diverse animal models [24]

FAQ: Prevention and Risk Mitigation

Q: What is the most effective strategy for preventing viral contamination? A comprehensive, multi-layered approach is essential [25]:

- Rigorous sourcing: Obtain cell lines from reputable banks that provide viral testing certification

- Raw material control: Use gamma-irradiated serum and animal-free reagents when possible

- Process design: Implement multiple orthogonal viral clearance steps in downstream processing

Q: Can I use antibiotics to prevent viral contamination? No. Antibiotics are ineffective against viruses, though they may control bacterial and mycoplasma contaminants [23] [28].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Viral Detection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive strategy for detecting viral contaminants in cell cultures:

Essential Detection Methods

Table: Viral Detection Method Comparison

| Method | Principle | Applications | Sensitivity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR/RT-PCR | Amplification of viral nucleic acid sequences | Detection of specific known viruses (e.g., EBV, MVM) | High for targeted viruses | Only detects pre-defined targets; misses novel viruses |

| In Vitro Virus Assay | Inoculation onto multiple detector cell lines; observation for CPE, hemadsorption | Broad detection of viruses capable of growing in tissue culture | Variable; depends on virus and cell line permissivity | Not all viruses produce CPE; limited detector cell range |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Unbiased sequencing of all nucleic acids in sample | Detection of unknown adventitious agents; no prior selection | High with sufficient depth | Requires specialized resources and bioinformatics expertise |

| Electron Microscopy | Direct visualization of virus particles in samples | Detection of intracellular viruses; no amplification needed | ~10^6 particles/mL | Lower sensitivity; requires specialized equipment |

| In Vivo Assay | Injection into suckling mice, embryonated eggs | Detection of viruses that don't grow well in tissue culture | Variable | Ethical concerns; decreasing regulatory acceptance |

Viral Risk Mitigation Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the three complementary approaches to viral risk mitigation in bioprocessing:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Viral Contamination Management

| Reagent/Supply | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gamma-Irradiated Fetal Bovine Serum | Cell culture supplement | Viral inactivation through irradiation; superior to heat-inactivated only [27] |

| PCR/RT-PCR Kits | Viral nucleic acid detection | Target specific contaminants (e.g., EBV, MVM); validate sensitivity for your application [25] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Unbiased detection of adventitious agents | Comprehensive contaminant screening; requires bioinformatics support [25] |

| Viral Filtration Systems | Physical removal of viral particles | Nanofilters (≤20 nm) for parvovirus removal; validate for specific process [25] |

| Mycoplasma Testing Kits | Detection of common co-contaminants | PCR-based or Hoechst stain methods; mycoplasma increases vulnerability to viral infection [23] |

| Animal-Free Recombinant Trypsin | Cell passage and subculturing | Eliminates risk of animal-derived viral contaminants present in porcine trypsin [27] |

| Certified Cell Culture Media | Nutrient supply without contaminants | Low-endotoxin, certified composition reduces variable introduction [23] |

Troubleshooting Guides

How do I identify and address chemical contamination in my cell cultures?

Problem: Unexplained changes in cell health or erratic experimental results, potentially caused by non-biological contaminants.

Solution: Chemical contamination arises from non-living substances that interfere with cell processes. Common sources include impurities in water, media, sera, disinfectant residues, and plasticizers leaching from equipment [4] [29] [30].

Detection and Diagnosis:

- Observe Cell Behavior: Look for signs of acute toxicity, such as slow growth, vacuole appearance, sloughing, decrease in confluency, and cell rounding [4].

- Identify the Source: Systematically review and replace reagents like media, water, and serum one at a time to isolate the contaminated component [29].

- Test for Endotoxins: Use a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay to detect endotoxins, which can significantly affect cell metabolism. Always source media and sera from suppliers that provide endotoxin testing certification [29].

Corrective Action:

- Discard Contaminated Reagents: Immediately dispose of any suspected reagents [29].

- Use High-Quality Water: Always use laboratory-grade water for preparing buffers and media [29].

- Thoroughly Rinse Labware: Ensure all reusable glassware and equipment are thoroughly rinsed and air-dried to remove detergent or disinfectant residues, as autoclaving does not eliminate these chemicals [29].

My cell lines are not behaving as expected; could they be cross-contaminated?

Problem: Inconsistent experimental data or unexpected morphological changes in a cell culture, potentially due to misidentification or overgrowth by another cell line.

Solution: Cross-contamination is a serious, often undetected problem. One study found over 15% of cell culture studies use misidentified or cross-contaminated cell lines [31].

Detection and Diagnosis:

- Routine Authentication: Implement mandatory cell line authentication using methods like Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling, karyotype analysis, or isoenzyme analysis [4] [32].

- Monitor Morphology: Regularly check cells for unexpected changes in morphology or growth rate compared to established baselines [32].

Corrective and Preventive Action:

- Work with One Cell Line: Only handle one cell line at a time in the biosafety cabinet to prevent accidental mix-ups [5] [32].

- Use Dedicated Reagents: Assign separate bottles of media, reagents, and pipettes for each cell line [5].

- Label Meticulously: Clearly label all flasks and plates with the cell line name, passage number, and date [32].

- Source Authentically: Obtain cell lines only from reputable cell banks that provide authentication data [5] [4].

How can I detect and eradicate a mycoplasma contamination?

Problem: Mycoplasma contamination is common, affecting an estimated 5-30% of cell cultures, and is typically invisible to the naked eye without altering culture conditions [5] [29].

Solution: Due to their small size and lack of a cell wall, mycoplasma are resistant to common antibiotics and require specific detection and eradication methods [5] [29].

Detection Protocols:

- PCR-Based Testing: This is a highly sensitive and common method for detecting mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences [5] [32].

- Fluorescent Staining: Use DNA-binding dyes like Hoechst 33258 to stain a fixed cell monolayer. Under fluorescence microscopy, mycoplasma appear as tiny, bright particles on the cell surface or in intercellular spaces (see diagram below) [5] [29].

- Commercial Kits: Many companies offer specialized mycoplasma detection kits based on PCR, ELISA, or enzymatic reactions [32] [1].

Eradication Protocol (Use with Caution):

- Consider Discarding: The best practice for a contaminated culture is to autoclave it and discard it. Only attempt eradication if the cell line is irreplaceable [5] [30].

- Quarantine: Move the contaminated culture to an isolated hood, preferably in a separate room [5].

- Antibiotic Treatment: Treat with commercially available antibiotics effective against mycoplasma, such as quinolone derivatives (e.g., Mycoplasma Removal Agent), ciprofloxacin, or a combination of tiamulin and minocycline (BM-Cyclin). Always follow the supplier's instructions for concentration and duration [5].

- Post-Treatment Validation: After treatment, culture the cells in antibiotic-free medium for 4-6 passages and re-test for mycoplasma to confirm eradication [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The most overlooked sources are often procedural. These include using the same media bottle or pipettor for different cell lines, working with multiple cell lines simultaneously in the hood, and inadequate cleaning between handling different lines [5] [31] [32]. Aerosol generation during pipetting is another subtle risk, which can be mitigated by using filter tips [31].

Are antibiotics a reliable long-term solution for preventing biological contamination?

No, routine use of antibiotics is strongly discouraged. Their continuous use can promote the development of antibiotic-resistant strains, hide low-level contaminations (like mycoplasma), and can be toxic to cells or interfere with cellular processes under investigation [4] [29] [32]. Antibiotics should only be used as a last resort for short-term applications [4].

How can I prevent chemical contamination from my water source?

Always use laboratory-grade water for preparing all media and buffers [29]. Ensure water purification systems are well-maintained. For critical applications, consider using sterile, endotoxin-tested water from commercial suppliers to rule out water as a source of ions, endotoxins, or organic impurities [29].

My culture is contaminated with mold. What should I do?

Discard the contaminated culture immediately by autoclaving. Decontaminate the incubator and biosafety cabinet thoroughly, including shelves, door gaskets, and water trays, as fungal spores are airborne and persistent [32] [1]. Review your aseptic technique and ensure HEPA filters in your hood and incubator are functioning correctly [32].

Quantitative Data on Contamination

The tables below summarize the characteristics and detection methods for common contaminants to aid in identification and reporting.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Microbial Contaminants

| Contaminant Type | Visual/Microscopic Signs | Effect on Medium pH | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria [5] [4] [32] | Turbidity; tiny, moving granules between cells. | Sharp drop (acidic, yellow). | Very rapid. |

| Yeasts [5] [4] | Turbidity; ovoid or spherical particles that bud. | Little change initially, increases with heavy infection. | Rapid. |

| Molds/Fungi [5] [4] | Thin, filamentous mycelia; fuzzy structures. | Changes sometimes; usually increases with heavy infection. | Moderate to rapid. |

| Mycoplasma [5] [29] [32] | No turbidity; not visible under standard microscope. | No direct change. | Slow, often unnoticed. |

Table 2: Recommended Detection Methods for Contaminants

| Contaminant Type | Primary Detection Methods | Recommended Testing Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria, Fungi, Yeast [4] [29] | Visual inspection, microscopy, microbial culture. | Daily (microscopy), routine culture. |

| Mycoplasma [5] [29] [32] | PCR, fluorescent DNA staining (Hoechst), ELISA. | Every 1-2 months; for all new cell lines. |

| Viral [4] [29] [32] | PCR/RT-PCR, immunoassays (ELISA), electron microscopy. | Prior to use for bioproduction; as required for safety. |

| Cross-Contamination [4] [32] [1] | STR profiling, karyotype analysis, isoenzyme analysis. | Upon acquisition and every 6-12 months thereafter. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Routine Screening for Mycoplasma via PCR

Principle: This method amplifies mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences, offering high sensitivity and specificity [32].

- Sample Collection: Collect 0.5 - 1 mL of cell culture supernatant from a test culture that has been without antibiotics for at least 3-5 days.

- DNA Extraction: Extract total DNA from the sample using a commercial DNA extraction kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- PCR Setup: Prepare a PCR master mix containing primers specific for conserved mycoplasma genes (e.g., 16S rRNA). Include both positive (known mycoplasma DNA) and negative (nuclease-free water) controls.

- Amplification: Run the PCR using the recommended cycling conditions for your primer set.

- Analysis: Analyze the PCR products by gel electrophoresis. A positive result is indicated by a band of the expected size in the test sample and positive control, absent in the negative control.

Protocol 2: Cell Line Authentication by STR Profiling

Principle: STR profiling analyzes highly polymorphic short tandem repeat loci in the genome to create a unique DNA fingerprint for a cell line [32].

- DNA Sample Preparation: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from the cell line in question.

- Multiplex PCR: Amplify a standard set of STR loci (e.g., the 8-core loci used by ATCC) using fluorescently labeled primers.

- Capillary Electrophoresis: Separate the amplified fragments by size using capillary electrophoresis.

- Data Analysis: Software analyzes the fragment sizes to generate an allelic profile for each locus.

- Comparison: Compare this profile to reference profiles in a database (e.g., ATCC, DSMZ). A match confirms authenticity, while a mismatch indicates cross-contamination or misidentification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function & Importance | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma-Tested FBS [32] [1] | Provides essential growth factors for cells. | Source from suppliers that provide certification for being tested and free of mycoplasma and viruses. |

| Endotoxin-Tested Media [29] | The nutrient base for cell growth. | High levels of endotoxins can adversely affect cell metabolism and experimental outcomes. |

| Sterile, Filtered Pipette Tips [31] | Prevents aerosol contamination from entering pipettors, reducing cross-contamination risk. | Use filter tips as a standard practice for all cell culture work. |

| 70% Ethanol / IMS [21] [1] | Standard disinfectant for decontaminating gloves, work surfaces, and equipment outside the biosafety cabinet. | Effective concentration for killing bacteria; must be used liberally throughout the procedure. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit [5] [32] | Allows for routine in-house screening for mycoplasma contamination. | Kits are available based on PCR, fluorescence, or enzymatic methods. |

| STR Profiling Kit/Service [32] | The gold-standard method for authenticating cell lines and ruling out cross-contamination. | Can be performed as a service by core facilities or commercial cell banks. |

Modern Arsenal for Contamination Detection: From Traditional Tests to Rapid Tech

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Sterility Test Failures and Inconclusive Results

Problem: A sterility test conducted according to USP <71> has shown microbial growth (a positive result), or the results are questionable, potentially jeopardizing a product batch.

Solution: Follow this structured investigation flow to determine the root cause—whether it's a true product contamination or a false positive from laboratory error.

Investigation Workflow:

Actionable Steps:

- Confirm and Identify Growth: Sub-culture the organism from the positive test media to isolate it for identification [33].

- Compare with Environmental Isolates: Compare the identified microorganism against the environmental monitoring (EM) and personnel monitoring (PM) data from the day of testing. If a match is found, the test is considered invalid due to laboratory error and must be repeated [33].

- Review Aseptic Technique: If no EM match is found, conduct a thorough review of aseptic techniques. This includes checking records for media sterilization, equipment assembly, and technician gowning certification [33].

- Check Method Suitability: Verify that a valid Method Suitability Test (also known as Bacteriostasis and Fungistasis test) was conducted for the product. This test confirms that the product itself does not inhibit microbial growth, ensuring the test's validity [33] [34].

- Final Determination:

Guide 2: Addressing Undetected Contamination in Cell Cultures

Problem: Despite passing routine sterility checks, cell cultures exhibit unexplained issues like reduced growth rates, altered metabolism, or strange morphology, suggesting the presence of contaminants not detected by standard USP <71> methods.

Solution: USP <71> is designed for sterile products and may not detect all contaminants in a dynamic cell culture system. Implement a broader detection strategy targeting specific, hard-to-detect organisms.

Diagnosis and Resolution Workflow:

Actionable Steps:

- Expand Detection Methods:

- For Mycoplasma: Routinely use DNA staining (e.g., Hoechst stain) or PCR-based methods, as these contaminants are invisible to standard light microscopy and can pass through 0.22 µm filters [23] [6].

- For Viruses: Implement PCR, electron microscopy, or in vivo testing, as these are not detected by culture-based sterility tests [27] [23].

- Review Aseptic Technique: Reinforce strict aseptic practices. This includes working with one cell line at a time, proper use of biological safety cabinets, and routine cleaning with 70% alcohol and 10% bleach [27] [23].

- Source Control: Use gamma-irradiated serum and source cell lines from reputable banks that provide viral and mycoplasma testing certifications [27] [23].

- Containment and Elimination:

- Immediately quarantine any suspect cultures.

- Antibiotics or antimycotics can be attempted for bacterial or fungal contamination but use them cautiously as they can mask low-level contamination and lead to resistant strains [23].

- For valuable cultures contaminated with mycoplasma, specialized elimination kits or services may be an option [23]. Often, discarding the culture is the safest course of action to protect other cells in the laboratory.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How does USP <71> ensure its sterility testing methods are reliable?

USP <71> mandates two critical validation tests to ensure reliability [33] [34]:

- Growth Promotion Test (GPT): This test verifies that the culture media (FTM and TSB) can support the growth of a small number of representative microorganisms. It confirms that a "no growth" result is due to the product's sterility, not faulty media.

- Method Suitability Test (Bacteriostasis and Fungistasis): This test confirms that the product itself does not contain antimicrobial properties that would inhibit microbial growth during the test. The product is inoculated with a low level of specific microorganisms, and the method must be able to recover them. If inhibition occurs, the method is modified, for example, by adding neutralizers or increasing rinse volumes, to ensure accurate detection.

What are the primary limitations of USP <71> and other culture-based methods?

While considered the gold standard, these methods have inherent limitations:

- Lengthy Incubation Time: The mandatory 14-day incubation period can create significant delays in product release [33] [34].

- Inability to Detect All Contaminants: The method may not support the growth of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) organisms, certain fastidious bacteria, or viruses [35].

- Low Throughput and Manual Labor: The process is labor-intensive and not easily scalable for high-throughput needs [36].

- Potential for Human Error: As a manual process, it is susceptible to false positives due to accidental contamination during testing [33].

When are automated blood culture systems a suitable alternative to the compendial USP <71> method?

Automated systems like BacT/Alert can be suitable alternatives but require careful validation. A 2019 study found that the BacT/Alert system incubated at 32.5°C, when paired with a supplemental Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) plate, performed equivalently to the manual USP <71> method after extended incubation [36]. In contrast, the Bactec FX system was found to be suboptimal, particularly for detecting environmental molds, highlighting that not all automated systems are equally effective for product sterility testing [36].

What is the difference between a Sterility Test (USP <71>) and a Bioburden Test?

These are two distinct types of microbial control tests:

- Sterility Test (USP <71>): A qualitative, pass/fail test designed to demonstrate the absence of viable microorganisms in a stated portion of a sterile product batch. It is a release test for products labeled "sterile" [33] [37].

- Bioburden Test: A quantitative test used for non-sterile products or for in-process monitoring of sterile products. It estimates the total number of viable microorganisms present in or on a product before terminal sterilization. This is not a direct measure of sterility but a quality control metric [37].

Table 1. Performance Comparison of Sterility Testing Methods Against Compendial USP <71> [36]

| Testing Method | Sensitivity at <144 hrs (vs. USP <71>) | Sensitivity with Extended Incubation & Visual Inspection | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compendial USP <71> | 84.7% (Baseline) | 95.7% (Baseline) | Lengthy process (14 days), labor-intensive |

| BacT/Alert at 32.5°C | 78.8% (Not Significant) | 89.0% (Not Significant) | Requires supplemental SDA plate for optimal fungal detection |

| Bactec FX | 64.4% (Significantly Lower) | 71.2% (Significantly Lower) | Suboptimal for detecting environmental molds |

Table 2. Recovery Rates of Sampling Methods for Duodenoscope Surveillance [38]

| Organism | Modified ESGE Protocol (MEP) | Interim CDC Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | 80.3% ± 23.5 | 46.2% ± 12.6 |

| E. coli | 46.0% ± 13.0 | 25.6% ± 7.8 |

| K. pneumoniae | 66.0% ± 9.7 | 32.1% ± 3.2 |

| E. faecium | 67.2% ± 15.6 | 60.2% ± 4.2 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Materials for Sterility Testing and Contamination Control

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Supports growth of potential contaminants. | Fluid Thioglycollate Medium (FTM): For anaerobes and aerobes. Soybean-Casein Digest Medium (TSB): For aerobes and fungi [33]. |

| Membrane Filter | Traps microorganisms from filterable products. | 0.45 µm pore size filter, used in Membrane Filtration method [33]. |

| Neutralizing Agents | Counteracts antimicrobial properties in a product. | Added to rinse fluids or media during Method Suitability to ensure microbial recovery [33] [34]. |

| RODAC Plates | For environmental and personnel monitoring. | Agar plates used to sample surfaces and gloves to monitor aseptic processing areas [33]. |

| DNA Stains & PCR Kits | Detects non-culturable contaminants. | Hoechst Stain: For mycoplasma visualization [23]. PCR Kits: For specific, rapid detection of mycoplasma and viruses [23] [6]. |

| Disinfectants | Maintains sterile working environment. | Rotation of 70% alcohol, 10% bleach, and sporicidal agents is recommended [33] [27]. |

Within cell culture research and the development of advanced therapies, microbial contamination poses a significant risk to experimental integrity and patient safety. Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs) are advanced technologies designed to detect, identify, and quantify microorganisms faster and more accurately than traditional, labor-intensive culture-based methods [39]. This technical support center focuses on two automated microbial detection systems—BACTEC and BACT/ALERT 3D—within the broader context of a thesis on cell culture microbial contamination. These systems are critical for researchers and drug development professionals working with sensitive biological materials, including cell therapy products (CTPs), where timely contamination detection can be life-saving for critically ill patients awaiting treatment [18] [40].

Traditional sterility testing methods, based on microbiological culture, are labor-intensive and can require up to 14 days to detect contamination [18]. This delay is unacceptable for many advanced therapies with short shelf lives. RMMs address this need for speed, automation, and improved accuracy, directly supporting the contamination control strategies required in modern pharmaceutical manufacturing and biotechnological research [39] [41].

The BACT/ALERT 3D instrument is a state-of-the-art, automated microbial detection system. Its modular design, easy touch-screen operation, and flexible data management options make it suitable for laboratories of all sizes [42] [43].

Key Features, Benefits, and Technical Specifications

The system is primarily used for detecting microorganisms in blood and sterile body fluids [42]. It utilizes patented colorimetric sensor technology that changes color in response to carbon dioxide produced by microbial growth, allowing for early detection and immediate intervention [43].

Table 1: Key Features and Benefits of BACT/ALERT 3D

| Feature | Benefit for Research and Diagnostics |

|---|---|

| Modular, Scalable Design | Adapts to laboratory space and volume needs; the same footprint as smaller platforms with 2-3 times the bottle capacity [43]. |

| Easy-to-Use Touchscreen | Facilitates cross-training, reduces errors, and minimizes labor needs [42] [43]. |

| Plastic, Shatter-Resistant Bottles | Reduces biohazard exposure risk and offers cost-effective shipping and disposal [42] [43]. |

| Flexible Data Management | Options range from basic (Select) to advanced LIS connectivity (Signature), supporting compliance with data integrity regulations [42] [41]. |

| Rapid Response Time | Low false-positive rate and rapid time-to-detection enable researchers to do more in less time with greater accuracy [42]. |

Table 2: Technical Specifications for BACT/ALERT 3D Configurations

| Parameter | BACT/ALERT 3D 120 Combo | BACT/ALERT 3D 240 Incubator Module |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions (HxWxL) | 30.8 x 19.5 x 24.5 inches (77 x 48.8 x 61.2 cm) [43] | 36 x 19.5 x 24.3 inches (90 x 48.8 x 60.8 cm) [43] |

| Capacity | 120 cells (60 cells/drawer) [43] | 240 cells (60 cells/drawer) [43] |

| Weight (Loaded) | 216.5 lbs (98.3 kg) [43] | 233 lbs (105.8 kg) [43] |

| Power Consumption | 115 VAC, 640 Watts (typical) [43] | 115 VAC, 640 Watts (typical) [43] |

BACT/ALERT 3D Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard operational workflow for using the BACT/ALERT 3D system in a laboratory setting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of automated systems is highly dependent on the culture media used. The table below details key media bottles for the BACT/ALERT 3D system, which are designed to ensure the recovery of a wide variety of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria [42] [43].

Table 3: BACT/ALERT Culture Media Portfolio for Research

| Product Name | Media Type & Function | Specimen Type | Specimen Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| BACT/ALERT FA Plus [42] | Aerobic. FAN Plus media with Adsorbent Polymeric Beads (APB) to neutralize antimicrobials. | Blood or Sterile Body Fluids (SBF) | Up to 10 mL |

| BACT/ALERT FN Plus [42] | Anaerobic. FAN Plus media with APB for fastidious and anaerobic organisms. | Blood or SBF | Up to 10 mL |

| BACT/ALERT SA [42] | Standard Aerobic. For recovery and detection of aerobic microorganisms (bacteria and fungi). | Blood or SBF | Up to 10 mL |

| BACT/ALERT SN [42] | Standard Anaerobic. For recovery and detection of anaerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria. | Blood or SBF | Up to 10 mL |

| BACT/ALERT MP [42] | Mycobacteria. For recovery and detection of mycobacteria. | Digested or decontaminated specimens | 0.5 mL |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

This section addresses specific issues users might encounter during experiments with microbial detection systems.

Issue 1: Delayed or No Detection of Known Positives

- Potential Cause: Incorrect sample volume used, leading to a dilution effect that extends the time to detection (TTD).

- Solution: Verify that the recommended sample volume is used for the specific bottle type (e.g., up to 10 mL for FA/FN Plus bottles). Ensure samples are injected directly into the broth and not onto the sensor at the bottom [42].

Issue 2: High Rate of False-Positive Signals

- Potential Cause: Contamination during sample inoculation or bottle handling. Non-microbial gas production from certain sample types.

- Solution: Aseptically validate the sample collection and loading technique. Review the lot-specific quality control documentation for the media. For unique sample types, method suitability testing is recommended to establish a baseline TTD [42].

Issue 3: Instrument Does Not Recognize Loaded Bottles

- Potential Cause: Damaged or obsolete barcode labels on bottles. Malfunctioning barcode reader within the instrument drawer.

- Solution: Inspect bottle labels for integrity. Clean the barcode scanner window with a soft, lint-free cloth. If the problem persists, contact technical service for module diagnostics [43].

Issue 4: Communication Error with Laboratory Information System (LIS)

- Potential Cause: Incorrect data mapping or interface configuration between the BACT/ALERT 3D data management system (e.g., Signature) and the LIS.

- Solution: Verify the connectivity settings in the instrument software. Confirm that the data string format matches the LIS requirements. Consult with both the instrument and LIS support teams [42] [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does the detection technology in BACT/ALERT 3D work? The system uses a colorimetric sensor embedded in the bottom of each culture bottle. As microorganisms grow, they produce CO₂, which changes the color of the sensor. The instrument's optical system continuously monitors each bottle for this color change, signaling a positive result [42] [43].

Q2: What are the main advantages of using plastic culture bottles? Plastic bottles are shatter-resistant, which reduces the risk of biohazard exposure from broken glass. They are also lightweight, reducing shipping costs and making disposal easier and potentially more cost-efficient [42] [43].

Q3: Can the BACT/ALERT 3D system be used for sterility testing of cell therapy products (CTPs)? While the system is optimized for blood and sterile body fluids, its principle of automated, continuous monitoring aligns with the need for rapid sterility testing in CTP manufacturing. However, for final product release, the method must be validated according to regulatory standards for sterility testing [39]. Novel RMMs, such as UV spectroscopy with machine learning, are also emerging specifically for CTPs, offering results in under 30 minutes [18] [40].

Q4: What is the regulatory stance on using RMMs like BACT/ALERT 3D? Regulatory agencies (FDA, EMA) recognize RMMs as alternatives to conventional methods. The revised EU GMP Annex 1 explicitly encourages the use of modern technologies to improve contamination control [41]. However, implementing any RMM requires a validation process to demonstrate its equivalence or superiority to the pharmacopoeial method it is intended to replace [39] [41].

Q5: Our lab is considering implementing an RMM. What are the key challenges? The main challenges include the initial cost of investment, the need for technical expertise to operate and maintain the system, and the rigorous validation required for regulatory alignment. A successful implementation requires careful technology selection, feasibility studies, and change management [39] [41].

This technical support center provides essential guidance for implementing a novel method for detecting microbial contamination in cell cultures. This machine learning-aided UV absorbance spectroscopy technique represents a significant advancement over traditional sterility testing, reducing detection time from days to minutes while maintaining high sensitivity and specificity [18] [44]. The method is particularly valuable for cell therapy product (CTP) manufacturing, where timely administration of treatments can be life-saving for critically ill patients [40].

The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and experimental protocols will assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in successfully implementing this technology within their laboratories.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does machine learning-aided UV spectroscopy detect microbial contamination? This method combines ultraviolet light absorbance measurements with machine learning algorithms to identify contamination. Microorganisms in cell culture media alter the fluid's biochemical composition, which changes its UV absorbance spectrum. These spectral patterns serve as "fingerprints" that a trained one-class support vector machine (SVM) model recognizes as anomalous compared to sterile samples [44] [45]. The system provides a definitive yes/no contamination assessment within 30 minutes without requiring cell extraction or staining [40].

Q2: What are the key advantages over traditional sterility testing methods? Traditional sterility tests like USP <71> require 14 days for results, while rapid microbiological methods (RMMs) still need approximately 7 days [18]. This new approach offers:

- Speed: Results in <30 minutes [40]

- Sensitivity: Detection as low as 10 colony-forming units (CFUs) [44]

- Non-invasiveness: No cell extraction required [18]

- Label-free operation: No staining or tagging needed [44]

- Automation potential: Enables continuous culture monitoring [40]

Q3: What instrumentation is required to implement this method? The essential equipment includes:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer (standard commercial unit)

- Sample holder/cuvette with 10mm path length

- Computer system for machine learning analysis

- Optional: Automated sampling system for bioreactor integration [46] [45]

Q4: What microbial contaminants can this method detect? Research has successfully detected 7 microbial organisms spiked into mesenchymal stromal cell supernatants, though specific organisms beyond E. coli K-12 (ATCC 25404) aren't detailed in the available literature. Future research aims to broaden detection to a wider range of contaminants representative of cGMP environments [44] [40].

Q5: How does this method perform compared to USP <71> and BACT/ALERT 3D? The method detects E. coli contamination at 10 CFUs in approximately 21 hours, comparable to USP <71> (~24 hours) but longer than BACT/ALERT 3D (16 hours). However, it provides continuous monitoring capability and much faster analysis once samples are collected [44].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Contamination Detection Assay

Purpose: To detect microbial contamination in cell therapy products during manufacturing [44].

Materials:

- Cell culture supernatant samples (≤1 mL)

- UV-transparent cuvettes (10mm path length)

- Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Trained one-class SVM model

Procedure:

- Collect cell culture supernatant samples (1 mL volume) under aseptic conditions

- Transfer samples to UV-transparent cuvettes

- Measure absorbance spectra using UV-Vis spectrophotometer across appropriate wavelength range

- Input spectral data into trained one-class SVM model

- Record contamination prediction (yes/no output)

- For confirmed contamination, implement corrective actions and consider secondary confirmation with RMMs

Technical Notes:

- Sample preparation should be minimal with no additional reagents required

- Measurements should be performed in triplicate for statistical reliability

- The model should be trained on sterile samples from the specific cell type being monitored

Protocol 2: Model Training and Validation

Purpose: To develop and validate a machine learning model for contamination detection [44] [45].

Materials:

- Sterile cell culture media samples from multiple donors

- Selected microbial strains for spiking

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Machine learning environment (Python with scikit-learn recommended)

Procedure:

- Collect sterile cell culture media samples from various culture conditions

- Split samples into two groups: sterile control and experimental (spiked with microorganisms)

- Obtain UV absorbance spectra for all samples

- Use spectra from sterile samples exclusively to train a one-class SVM model

- Validate model performance using mixture of sterile and contaminated samples

- Calculate true positive and true negative rates to assess model accuracy

Technical Notes:

- Include samples from multiple donors to improve model robustness

- Test model across different cell types beyond those used in initial training

- Optimal performance achieved when excluding samples with anomalously high nicotinic acid content [44]

Performance Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Microbial Detection Methods

| Method | Detection Time | Sensitivity | Sample Volume | Labor Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional USP <71> | 14 days | ~10 CFUs | 1 mL | High [18] |

| Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs) | 7 days | ~10 CFUs | 1 mL | Moderate [18] |

| BACT/ALERT 3D | 16 hours | ~10 CFUs | 1 mL | Low [44] |

| ML-aided UV Spectroscopy | <30 minutes analysis | 10 CFUs | <1 mL | Low (automation compatible) [44] [40] |

Table 2: Detection Performance Across Donors

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mean True Positive Rate | 92.7% | All microorganisms tested [44] |

| Mean True Negative Rate | 77.7% | Across multiple donors [44] |

| Improved True Negative Rate | 92% | After excluding donor with high nicotinic acid [44] |

| Time to Detection (10 CFUs E. coli) | 21 hours | Comparable to USP <71> [44] |

Method Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagrams illustrate the experimental workflow and data analysis process for machine learning-aided UV absorbance spectroscopy.

Experimental workflow for contamination detection.

Data analysis pathway for contamination assessment.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Implementation

| Item | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Measures light absorption | Standard commercial unit, 220-700 nm range [46] |

| Cuvettes | Sample holder | Quartz or UV-transparent, 10mm path length [46] |

| Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Cultures | Demonstration model | Commercial donors, various sources [44] |

| Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS) | Control preparation | Standard formulation [44] |

| Microbial Strains | Method validation | 7 organisms including E. coli K-12 (ATCC 25404) [44] |

| Software | Machine learning analysis | Python with scikit-learn, custom algorithms [44] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Model Performance with High False Positive Rates

- Potential Cause: Spectral interference from compounds like nicotinic acid in certain donor samples [44]

- Solution: Pre-screen donors for anomalous metabolite levels or exclude problematic samples from training set

- Prevention: Include diverse donor samples in training to improve model robustness

Problem 2: Inconsistent Absorbance Measurements

- Potential Cause: Air bubbles or particulate matter in samples [46]

- Solution: Centrifuge samples before analysis or use filtration to remove debris

- Prevention: Ensure proper sample preparation techniques and cuvette handling

Problem 3: Limited Detection Range for Microbial Species

- Potential Cause: Model trained on insufficient variety of contaminants [40]

- Solution: Expand training set to include more microbial species common to cGMP environments

- Prevention: Continuously update model with new contamination data as available

Problem 4: Difficulty Integrating with Bioreactor Systems

- Potential Cause: Manual sampling introduces variability and contamination risk [45]

- Solution: Implement automated sampling systems for closed-loop operations

- Prevention: Design integrated sampling ports specifically for spectroscopic analysis

Future Directions

Ongoing research aims to expand this technology's capabilities by:

- Broadening detection to encompass more microbial contaminants representative of cGMP environments [40]

- Testing model robustness across diverse cell types beyond mesenchymal stromal cells [18]

- Developing complete automated monitoring systems integrated with bioreactors [45]

- Exploring applications beyond cell therapy, such as food and beverage quality control [40]

For additional technical support, researchers are encouraged to consult the primary literature and consider collaborative opportunities with developing institutions to further refine this promising technology.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Instrumental and Data Analysis Issues

Q1: My GC-IMS analysis shows poor separation of volatile compounds, resulting in overlapping peaks. What could be the cause and how can I resolve this?

A: Poor peak separation can often be attributed to issues with the chromatographic column or incorrect method parameters. First, ensure the GC column (e.g., MXT-5 or similar wide-bore column) is properly conditioned and not degraded [47]. Verify the carrier gas flow rate; nitrogen is typically used, and an unstable or incorrect flow can compromise separation [47]. Method parameters such as the column temperature and the ramp rate should be optimized for your specific analytes. Increasing the GC runtime can sometimes improve resolution, as a longer column (e.g., 15m) provides more theoretical plates for separation [47].

Q2: The signal intensity from my GC-IMS is weak or inconsistent when analyzing microbial cultures. What steps should I take?

A: Weak signals often stem from sampling procedure inefficiencies. Focus on the headspace sampling method. The sampling bottle should be sealed and incubated (e.g., at 60°C for 10 minutes) to allow sufficient accumulation of volatile metabolites in the headspace [47]. Ensure the injection volume (typically 1 mL of headspace gas) is correctly set [47]. For microbial cultures, using a direct method—where bacteria are cultured directly in the sampling bottle—significantly improves the accumulation and detection of mVOCs compared to transferring an aliquot of culture (indirect method) [47]. Also, confirm that the Ion Mobility Spectrometer's drift gas is pure and flowing correctly, as impurities can quench the signal.

Q3: How can I differentiate between specific microbial species in a mixed culture using GC-IMS data?

A: Identifying species in a mixed culture relies on pattern recognition and multivariate data analysis rather than a single unique marker. GC-IMS generates a unique volatile metabolite "fingerprint" for pure and mixed cultures [48] [47]. Follow this data analysis workflow:

- Acquire Reference Spectra: First, run pure cultures of the expected microorganisms (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa) to establish a library of known patterns [47].

- Conduct Pattern-Based Analysis: Use software like LAV (G.A.S.) to mark significant peaks and compare the overall 2D spectrum of your mixed sample against the reference library [47].

- Apply Statistical Models: Employ Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) to the GC-IMS data. These models can differentiate between microorganisms and even separate pure from mixed cultures with high accuracy based on the combined VOC profile [48].

Sample Preparation and Contamination

Q4: I am detecting unexpected volatile compounds in my chromatograms. What are potential sources of this contamination?

A: Unexpected peaks typically indicate contamination from the sample preparation process or the culture medium itself.

- Culture Medium: The growth medium (e.g., Thioglycolate medium) contains its own VOCs. Always run a blank sample of the sterile medium under identical conditions and subtract its background signal from your experimental data [47].

- Reagents and Labware: Impurities in solvents or VOCs leaching from plastic tubes and septa can contaminate the headspace. Use high-purity reagents and inert glassware whenever possible.

- Cross-Contamination: Ensure proper cleaning of sampling bottles and the automatic sampler needle between runs to prevent carryover [47].

Q5: What is the best way to prepare and introduce my cell culture sample into the GC-IMS to maximize detection of microbial VOCs (mVOCs)?

A: The sample introduction method is critical for sensitive detection of mVOCs.

- Recommended: Direct Method. Inoculate the culture medium directly in the headspace sampling vial and incubate it to allow the mVOCs to accumulate. This method concentrates the volatile metabolites and leads to a stronger, more representative signal [47].

- Alternative: Indirect Method. Transfer 1 mL of a pre-grown culture to the sampling vial. This method is less effective as mVOCs can be lost during transfer [47].