Cross-Contamination of Cell Lines: Causes, Consequences, and Cutting-Edge Solutions for Reliable Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cell line cross-contamination, a critical and persistent issue that compromises the validity of biomedical research and drug development.

Cross-Contamination of Cell Lines: Causes, Consequences, and Cutting-Edge Solutions for Reliable Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cell line cross-contamination, a critical and persistent issue that compromises the validity of biomedical research and drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental causes and far-reaching consequences of contamination, including invalidated research, financial losses, and risks to therapeutic product safety. The content delivers actionable methodological guidance for authentication techniques like STR profiling, outlines robust troubleshooting and optimization strategies for laboratory practices, and establishes a framework for validation and compliance with growing journal and funding agency requirements. By synthesizing current data and best practices, this article serves as an essential resource for safeguarding research integrity.

The Silent Scourge: Understanding the Causes and Alarming Impact of Cell Line Contamination

Defining Cell Line Cross-Contamination and Accidental Co-culture

Cell line cross-contamination and accidental co-culture represent a pervasive and persistent challenge in biomedical research, with potentially devastating consequences for data validity, therapeutic development, and scientific reproducibility. This phenomenon occurs when a cell culture is inadvertently contaminated with another cell line, leading to the overgrowth and replacement of the original culture, or when multiple distinct cell types grow together unintentionally in a shared medium [1]. Despite being a recognized problem since the 1950s, cross-contamination remains a significant issue in research laboratories worldwide, with estimates suggesting that 15-20% of cell lines currently in use may not be what they are documented to be [2]. The implications extend beyond mere inconvenience, as compromised cell lines can invalidate research findings, undermine the comparison of results across different laboratories, and diminish the utility of cell culture for medical applications [1]. Within the broader context of research on cross-contamination causes, understanding the mechanisms, consequences, and prevention of cell line cross-contamination is fundamental to ensuring scientific integrity and advancing reliable drug development.

Defining the Problem: Scope and Consequences

What is Cell Line Cross-Contamination?

Cell line cross-contamination refers to the accidental introduction of an exogenous cell line into a culture of another cell line. This typically occurs through procedural errors in the laboratory, such as accidental inoculation with another cell suspension, mislabeling of culture vessels, thawing of incorrect frozen stocks, or simultaneous handling of multiple cell lines within the same workspace [1] [2]. The problem is particularly insidious because, unlike microbial contamination, cross-contamination is not readily detectable through visual inspection alone [1]. Faster-growing contaminant cells can gradually displace the original cell population, eventually completely overtaking the culture without obvious signs of abnormality to the untrained eye.

What Constitutes Accidental Co-culture?

Accidental co-culture describes the unintended growth of more than one distinct cell type together in a culture medium [1]. While intentional co-culture systems are valuable experimental tools for studying cell-cell interactions, accidental co-culture is problematic because it can compromise the genotypic and phenotypic stability of the desired cell line and seriously undermine experimental results [1]. In stem cell research specifically, accidental co-culture poses substantial risks, as the engraftment of undifferentiated or incorrectly differentiated cells has been associated with tumorigenic or immunogenic risks in recipients [1].

Quantifying the Problem: Prevalence and Impact

The scale of cell line cross-contamination is substantial, with the International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC) maintaining a register of misidentified cell lines that contained 576 entries as of June 2021 [3]. Historical data reveal the persistent nature of this issue, with one early study finding that 30% of human cell lines were incorrectly designated and 14% were of the wrong species [1].

Table 1: Most Frequent Cell Line Contaminants Based on ICLAC Data

| Contaminating Cell Line | Number of Affected Cell Lines | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| HeLa | 113 | Human cervical adenocarcinoma |

| T-24 | 18 | Human bladder carcinoma |

| HT-29 | 12 | Human colon carcinoma |

| CCRF-CEM | 9 | Human acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| K-562 | 9 | Human chronic myeloid leukemia |

| U-937 | 8 | Human lymphoma |

| OCI/AML2 | 8 | Human acute myeloid leukemia |

| Hcu-10 | 7 | Human esophageal carcinoma |

| M14 | 7 | Human melanoma |

The consequences of undetected cross-contamination are far-reaching. Scientifically, it compromises experimental results and leads to publication of irreproducible data. Financially, the costs are substantial, with one estimate suggesting that HeLa cell contamination alone causes financial losses of approximately $10 million annually [1]. Ethically, the use of misidentified cell lines represents a significant waste of research resources and can potentially misdirect clinical research pathways.

Mechanisms and Causes of Cross-Contamination

Common Pathways for Contamination

Cross-contamination typically occurs through several well-established pathways in the laboratory setting. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing effective prevention strategies.

Direct Inoculation: The accidental introduction of even a minute quantity of another cell suspension (as little as a single drop) or the accidental reuse of a pipette for different cell lines can introduce contaminants that may eventually completely displace the original culture [1].

Mislabeling and Misidentification: Errors in labeling culture vessels or misreading labels can lead to confusion about the identity of cell lines [1]. This is particularly problematic when retrieving frozen stocks from storage, as thawing an incorrect vial can introduce an entirely different cell line into the laboratory workflow.

Simultaneous Handling of Multiple Cell Lines: Working with more than one cell line in a biological safety cabinet at the same time and using the same equipment (media reservoirs, pipettes, etc.) for different cell lines dramatically increases the risk of cross-contamination [1] [4].

Improper Cell Banking Practices: Inadequate documentation of frozen stocks, improper labeling of vials, and failure to maintain accurate inventory records can all contribute to cross-contamination events [2].

The Special Case of HeLa Contamination

The HeLa cell line, derived from cervical cancer cells in 1951, deserves particular attention due to its remarkable propensity for cross-contaminating other cultures. HeLa cells are characterized by their vigorous growth, immortality, and ability to readily adapt to different culture conditions, making them particularly effective at overtaking slower-growing cell lines [1] [2]. The first recognized case of cross-contamination involved HeLa cells, and they remain the most common contaminant today, affecting approximately 24% of compromised cell lines in the ICLAC database [1]. The video mentioned in the search results demonstrates how a single HeLa cell is sufficient to take over another cell line in culture [2].

Detection and Authentication Methods

A multi-faceted approach to cell line authentication is essential for detecting cross-contamination. Various methods with different strengths and applications are available to researchers.

Table 2: Cell Line Authentication Methods

| Method | Principle | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling | Analysis of highly polymorphic microsatellite regions using multiplex PCR | Gold standard for human cell line authentication; distinguishes between individuals | Primarily for intra-species identification; requires reference databases |

| Karyotyping | Examination of stained chromosomes for number and structure | Detects interspecies contamination; reveals gross genetic abnormalities | Labor-intensive; requires expertise in chromosome analysis |

| Isoenzyme Analysis | Electrophoretic separation of species-specific enzyme isoforms | Rapid species verification; robust and easily performed | Low reproducibility; limited discriminatory power |

| DNA Barcoding (COI Analysis) | Sequencing of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene | Species identification across diverse taxa | Less common for routine cell authentication |

| Morphological Analysis | Visual assessment of cell shape and growth characteristics | Simple, rapid preliminary assessment; requires expertise | Subjective; insufficient for definitive authentication |

| Mass Spectrometry with ANN | Analysis of global cellular patterns coupled with artificial neural networks | Can quantify contamination levels; provides phenotypic information | Emerging technology; requires specialized equipment |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

STR Profiling Methodology

STR profiling has emerged as the gold standard for human cell line authentication. The standard protocol involves:

DNA Extraction: High-quality genomic DNA is extracted from cell pellets using commercial kits, ensuring minimal degradation and sufficient quantity (typically 1-10 ng/μL).

Multiplex PCR Amplification: Simultaneous amplification of multiple STR loci (typically 8-17 regions) plus the amelogenin gene for gender identification using commercially available kits such as the Promega PowerPlex 18D system.

Capillary Electrophoresis: Separation of amplified fragments by size using capillary electrophoresis instruments.

Data Analysis: Fragment analysis software (e.g., ThermoFisher Scientific GeneMapper ID-X) determines allele sizes by comparison with internal size standards.

Profile Comparison: The resulting STR profile is compared against reference databases such as the ATCC STR database or the cell line's known STR profile. A match of at least 80% is generally required to confirm identity [5] [6].

Innovative Detection Approaches

Recent technological advances have introduced novel approaches for detecting cross-contamination:

Mass Spectrometric Fingerprinting with Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) This innovative method uses intact cell MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to generate global protein profiles of cells, which are then analyzed using artificial neural networks for pattern recognition [7]. The experimental workflow involves:

Sample Preparation: Cell pellets are washed with ammonium bicarbonate and mixed with sinapinic acid matrix solution.

MS Data Acquisition: Mass spectra are acquired in linear positive mode across an appropriate m/z range (e.g., 2,000-20,000 Da).

Calibration Mixtures: Two-component cell mixtures are prepared in known ratios to create training data for the ANN.

ANN Training: The neural network is trained using mass spectra databases of known calibration mixtures.

Quantitative Prediction: The trained ANN can then predict contamination levels in test samples, with demonstrated accuracy in quantifying mixtures of human embryonic stem cells with mouse embryonic stem cells or mouse embryonic fibroblasts [7].

Artificial Intelligence-Based Morphological Analysis Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) represent a promising approach for live cell identification based on morphological features [6]. The methodology includes:

Image Acquisition: Phase-contrast microscopy images are collected at consistent magnification (e.g., 50×).

Data Preprocessing: Gauss filtering and gray normalization for brightness balance and contrast enhancement.

Data Augmentation: Image scaling and gamma correction to teach the network size and illumination invariance.

Model Training: Using architectures such as bilinear CNN (BCNN) for fine-grained identification, trained on millions of image patches.

Validation: External validation of model specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy, with reported performance of 99.5% accuracy in identifying pure cell lines and 86.3% accuracy for detecting cross-contamination [6].

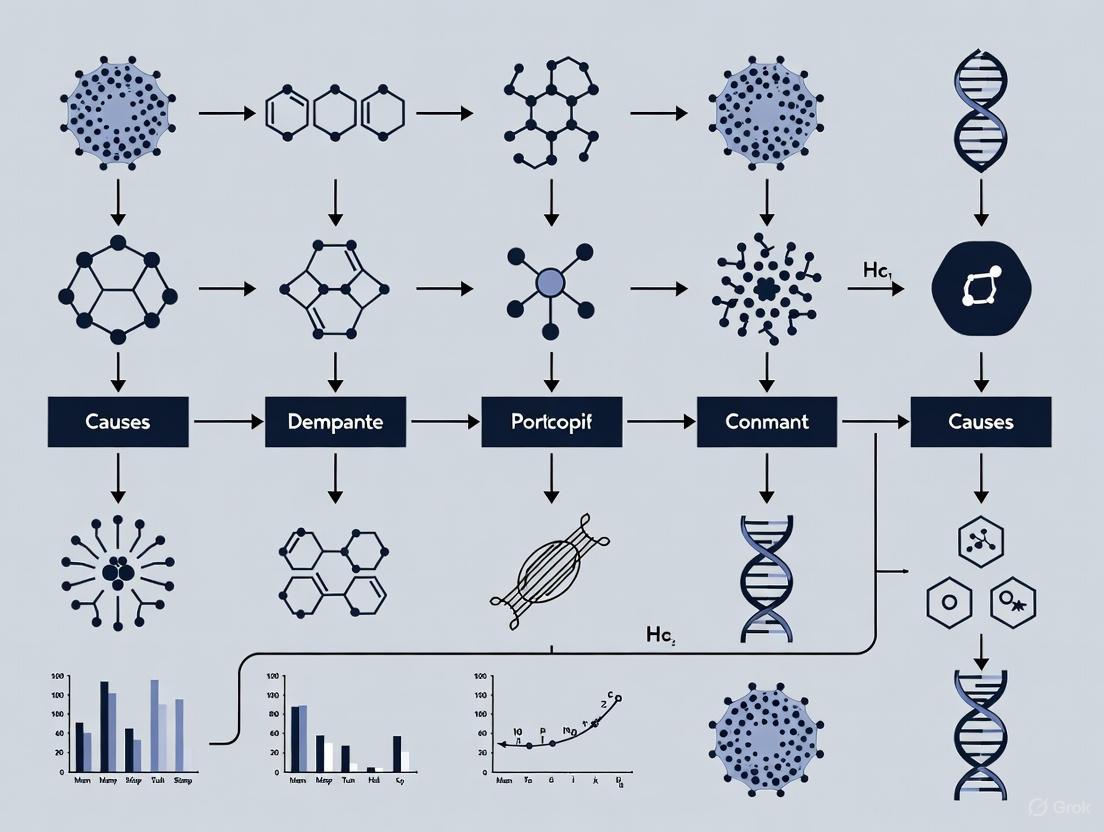

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for detecting cell line cross-contamination, from initial suspicion to final resolution:

Prevention Strategies and Best Practices

Preventing cell line cross-contamination requires a systematic approach encompassing technical practices, quality control measures, and laboratory management strategies.

Good Cell Culture Practice (GCCP)

Aseptic Technique: Maintain strict aseptic technique at all times, including proper use of biosafety cabinets, regular cleaning of work surfaces, and appropriate personal protective equipment [8] [4].

Sequential Handling of Cell Lines: Work with only one cell line at a time in the biosafety cabinet and thoroughly clean the workspace between different cell lines [4].

Dedicated Reagents and Equipment: Use separate media, sera, and other reagents for different cell lines whenever possible, with clear labeling for each specific cell line [4].

Proper Labeling: Clearly and indelibly label all culture vessels and frozen stocks with the cell line name, passage number, and date, using labels suitable for low-temperature storage [2].

Cell Banking and Authentication Protocols

Regular Authentication Testing: Implement a scheduled authentication program using STR profiling or other appropriate methods, particularly for new cell lines, before beginning critical experiments, and at regular intervals during extended culture [2] [5].

Systematic Cell Banking: Establish well-documented master and working cell banks, freeze stocks regularly at low passage numbers, and maintain accurate inventory records in multiple locations [4].

Passage Number Monitoring: Record and monitor passage numbers, establishing predetermined ranges for experimental use to avoid genetic drift associated with high passage numbers [5].

Source Verification: Obtain cell lines from reputable cell banks such as ATCC or ECACC whenever possible, and verify the identity of cell lines received from other laboratories [2] [4].

The following diagram outlines the key elements of a comprehensive cross-contamination prevention strategy:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Contamination Prevention

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| STR Profiling Kits (e.g., Promega PowerPlex 18D) | Multiplex PCR amplification of polymorphic STR markers | Gold standard for human cell line authentication; requires capillary electrophoresis instrumentation |

| Isoenzyme Analysis Kits | Electrophoretic separation of species-specific enzyme isoforms | Rapid species verification; useful for detecting interspecies contamination |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kits | Detection of mycoplasma contamination via PCR, ELISA, or fluorescent staining | Essential for comprehensive quality control; mycoplasma can affect cell behavior without visible signs |

| Cell Culture Antibiotics/Antimycotics | Suppression of bacterial and fungal growth | Should be used sparingly to avoid masking low-level contamination; not recommended for long-term culture |

| Authentication Services (e.g., ATCC, Abm) | Third-party cell line authentication | Provides independent verification; useful for laboratories without specialized equipment |

| Reference Databases (e.g., ATCC STR Database, ICLAC Register) | Comparison of authentication results | Essential for interpreting STR profiles; ICLAC maintains list of misidentified lines |

| Cryopreservation Media | Long-term storage of authenticated cell stocks | Enables creation of secure cell banks; should include controlled-rate freezing |

Cell line cross-contamination and accidental co-culture remain significant challenges that compromise research integrity and therapeutic development. The persistence of this problem decades after its initial identification underscores the need for continued vigilance and systematic approaches to cell culture management. Through a combination of robust authentication methods, adherence to good cell culture practices, proper cell banking procedures, and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and mass spectrometry, researchers can significantly reduce the risk of cross-contamination. As the scientific community increasingly recognizes the importance of cell line authentication, with growing requirements from journals and funding agencies, implementation of these practices becomes essential not only for research quality but for the very credibility of biomedical science. Within the broader context of research on cross-contamination causes, addressing cell line misidentification represents a fundamental prerequisite for generating reliable, reproducible scientific knowledge.

Cell line cross-contamination and misidentification represent a critical, persistent challenge in biomedical research, compromising data validity, jeopardizing drug development pipelines, and wasting invaluable scientific resources. Despite being a known issue for decades, the problem remains widespread, with ongoing research and publications relying on compromised cell lines. This whitepaper provides a technical overview of the most common contaminating cell lines—the "usual suspects"—and their documented prevalence within the research community. It further outlines standardized experimental protocols for cell authentication and provides a toolkit of resources to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in safeguarding their work against these pervasive contaminants, thereby upholding the integrity of scientific findings.

The Landscape of Contamination

Cross-contamination occurs when a foreign cell line is inadvertently introduced into and overtakes a culture of the intended cell line. The first cases were reported in the 1950s, and the issue has persisted despite increasing awareness [9] [1]. The consequences are severe: research on endothelium- or megakaryocyte-specific functions using the contaminated ECV-304 or DAMI cell lines, for instance, has in reality been conducted on bladder carcinoma and erythroleukemia cells, respectively, rendering the conclusions invalid [10].

The scale of the problem is significant. The International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC), a key body monitoring this issue, maintains a registry of known misidentified cell lines. As of April 2024, this registry listed 593 misidentified or cross-contaminated cell lines [11] [12]. A 2017 study investigating 278 tumor cell lines from 28 institutes in China found a staggering 46.0% (128/278) rate of cross-contamination or misidentification [13] [14]. This suggests that a substantial portion of the scientific literature may be built upon unreliable cellular models.

Prevalence of Major Contaminants

Quantitative data from multiple studies reveal a consistent pattern of contamination, with a small number of prolific cell lines responsible for the majority of incidents. The table below summarizes the most frequently reported contaminants.

Table 1: The Most Prevalent Contaminating Cell Lines

| Contaminating Cell Line | Actual Cell Type | Key Prevalence Data | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | Cervical adenocarcinoma | #1 most common contaminant; 113 entries (24%) in ICLAC database; caused 46.9% of cross-contamination in a 2017 study [1] [14]. | [10] [1] [14] |

| T-24 | Bladder carcinoma | Second most frequent contaminant; 18 entries in ICLAC database [1]. | [10] [1] |

| HT-29 | Colon carcinoma | Third most frequent contaminant; 12 entries in ICLAC database [1]. | [10] [1] |

| CCRF-CEM | T cell leukemia | Among common contaminants; 9 entries in ICLAC database [1]. | [10] [1] |

| K-562 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | Among common contaminants; 9 entries in ICLAC database [1]. | [10] [1] |

Quantitative Impact on Research

The contamination problem is not confined to historical cell lines. Recent analyses indicate that newly established cell lines, particularly those from certain geographical regions, may carry an even higher risk. The 2017 study highlighted a dramatic difference in contamination rates between cell lines established in China versus those from international sources.

Table 2: Contamination Statistics from a 2017 Study of 278 Cell Lines

| Category of Cell Lines | Number of Instances Tested | Misidentification/Cross-Contamination Rate | Most Common Contaminant (Percentage of Contaminated Lines) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Cell Lines | 278 | 46.0% (128/278) | HeLa (46.9%) [14] |

| Non-Chinese Model | 193 | 33.2% (64/193) | HeLa (39.1%) [14] |

| Chinese Model | 71 | 73.2% (52/71) | HeLa (67.3%) [13] [14] |

The pervasive nature of HeLa contamination is particularly noteworthy. The study identified HeLa as the contaminant in 67.3% (35/52) of the misidentified cell lines that were originally established in Chinese laboratories [13]. This underscores the aggressive nature of HeLa cells and the critical need for authentication regardless of a cell line's purported origin.

Mechanisms and Methodologies for Authentication

Understanding how contamination occurs and how to detect it is fundamental to prevention. Contamination can happen during routine handling through the accidental reuse of a pipette or by keeping multiple cell lines open in the safety cabinet simultaneously. More seriously, a cell line can be contaminated at its source during establishment, meaning it never actually existed as a genuine entity—these are classified as "virtual" cell lines [10] [1].

Standard Authentication Protocol: Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling

STR profiling is considered the gold standard method for cell line authentication. This technique analyzes the length of specific microsatellite loci that are highly variable between individuals, creating a unique genetic fingerprint for each cell line [13] [14].

Detailed Experimental Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: High-quality genomic DNA is isolated from the cell line in question using standard purification kits. The DNA concentration and purity (e.g., A260/A280 ratio) are quantified.

- PCR Amplification: Fluorescently labeled primers are used to amplify multiple (commonly 9 to 21) core STR loci in a multiplex PCR reaction. The number of loci used is critical; a 2017 study showed that a 9-loci comparison between HCCC-9810 and Calu-6 cells showed an 88.9% match, suggesting a common origin. However, a 21-loci comparison dropped the match to 48.2%, correctly indicating they were different cell lines [13].

- Capillary Electrophoresis: The amplified PCR products are separated by size using capillary electrophoresis. An internal size standard is run with each sample for precise fragment sizing.

- Data Analysis: The resulting electropherogram peaks are analyzed to determine the allele sizes at each locus, generating a unique STR profile for the sample.

- Comparison with Reference Databases: The generated STR profile is compared against reference databases from major cell banks like the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) or the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ). A match of 80% or higher is often used as a benchmark for authentication, though the use of more loci increases confidence [13] [14].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the STR profiling workflow.

Supplementary and Legacy Methods

While STR profiling is the current standard, other methods have been or are still used for authentication and detection of contamination:

- Karyotyping/Giemsa Staining: This classical cytogenetic technique was used by Walter Nelson-Rees to first expose the widespread contamination of cell lines by HeLa. HeLa cells have distinctive chromosome aberrations that are visible under a light microscope [10]. This method is useful for identifying gross chromosomal abnormalities and specific contaminants but lacks the specificity of STR profiling.

- Isoenzyme Analysis: This method exploits interspecies differences in the electrophoretic mobility of enzymes (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase). It is effective for detecting inter-species contamination but is less reliable for distinguishing between cell lines from the same species [1].

- DNA Barcoding (CO1 Assay): This method, used by some testing services like BioReliance, sequences a segment of the cytochrome c oxidase I (CO1) gene to identify species. It is particularly effective for detecting inter-species contamination [1].

Combating cell line misidentification requires a proactive approach. The following table outlines essential reagents, tools, and resources that should be part of every cell culture laboratory's standard operating procedures.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Resources

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| STR Profiling Service | Authentication Service | Provides the gold-standard method for confirming cell line identity. Often offered by specialized commercial providers or core facilities. |

| ICLAC Database | Informational Resource | The definitive registry of known misidentified cell lines. A crucial first check before acquiring or using a new cell line [11] [12]. |

| Cellosaurus | Informational Resource | A knowledge resource on cell lines that includes data on misidentified and contaminated lines, dynamically updated [10] [11]. |

| Reputable Cell Banks (e.g., ATCC, DSMZ) | Cell Source | Obtain cell lines from certified repositories that provide authentication data and passage numbers. Avoid using informal, non-authenticated stocks from other labs [8] [1]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Contamination Control | Regular testing is essential, as mycoplasma contamination is common and can alter cell behavior without causing turbidity. |

| Aseptic Technique | Laboratory Practice | The first line of defense. Includes using dedicated media per cell line, not handling multiple lines simultaneously, and regular decontamination of cabinets and incubators [8] [1]. |

A cornerstone of prevention is the consistent application of Good Cell Culture Practice (GCCP). This includes maintaining detailed records, using low passage numbers, cryopreserving stocks, and implementing routine authentication testing at the beginning of a project, upon receiving a new cell line, and at regular intervals during ongoing culture [3]. Journals and funding agencies are increasingly mandating such practices, making them an essential component of rigorous scientific research [11] [12].

Contamination in the laboratory represents a critical failure point that can compromise research integrity, invalidate experimental data, and lead to significant financial losses. This technical guide examines the primary pathways through which contamination occurs, focusing specifically on cell line cross-contamination as a pervasive problem in biomedical research. With studies suggesting that 15–20% of cell lines currently in use may be misidentified or cross-contaminated, the scientific community faces substantial reproducibility challenges [15]. This whitepaper details the common errors leading to contamination, provides methodologies for detection and authentication, and presents a comprehensive framework for implementing robust contamination prevention protocols in research and drug development settings.

The Scope of the Problem: Quantifying Laboratory Contamination

Contamination prevalence varies across laboratory types and processes, but available data reveals a concerning landscape of potential error sources.

Table 1: Prevalence of Laboratory Contamination and Error Types

| Contamination Type | Estimated Frequency | Primary Impacts | Common Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Misidentification | 15-20% of cell lines [15] | Invalid research data, literature pollution, wasted funding | STR profiling, karyotyping, isoenzyme analysis [15] |

| Pre-analytical Errors (Clinical Labs) | 46-68% of total lab errors [16] | Misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment, patient harm | Process control, audit trails |

| Particulate Contamination (GMP Manufacturing) | Batch-dependent; regulatory compliance failure | Batch rejection, financial losses, regulatory actions [17] | Environmental monitoring, USP 788 testing [17] |

| Microbial Contamination (Cell Culture) | Most common cell culture setback [8] | Culture loss, experimental variability, time delays | Microscopy, microbial culture, PCR [8] |

The persistence of cell line cross-contamination represents a particularly stubborn problem, with the International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC) listing 576 misidentified or cross-contaminated cell lines in its latest register [3]. The HeLa cell line, known for its vigorous growth, has been a frequent contaminant since the 1950s, with one analysis of 40 human thyroid cancer cell lines revealing only 23 unique profiles—many cross-contaminated with cell lines of non-thyroid origin [15].

Common Errors Leading to Cell Line Cross-Contamination

Procedural Lapses During Routine Cell Culture

Basic cell culture practices, when improperly executed, create multiple pathways for contamination:

Improper labeling and identification: Mislabeling flasks, misreading labels, and thawing incorrect frozen stocks directly introduce the wrong cell lines into experiments [18]. Accurate records of frozen cell banks must be maintained, with labels suitable for low-temperature storage to prevent detachment [15].

Inadequate spatial separation: Storing multiple cell lines together in safety cabinets or using one medium reservoir for multiple cell lines simultaneously creates opportunity for accidental cross-contact [18].

Shared equipment and reagents: Using the same pipettes, tools, or media between different cell lines without proper decontamination spreads contamination throughout the laboratory workflow [18].

Poor technique during manipulation: Accidentally inoculating one cell line with another or transferring cells to stock bottles represents a direct contamination vector that can go unnoticed [18].

System-Level Failures in Laboratory Management

Beyond individual technique, broader organizational practices contribute significantly to contamination risk:

Insufficient authentication protocols: Utilizing cell samples that have not been thoroughly tested and authenticated before use introduces unknown variables into research [18]. A 2004 survey revealed that more than one-third of researchers obtained cell lines from other laboratories, and almost half did not perform identity testing [15].

Inadequate training and oversight: Lack of proper training in aseptic technique combined with insufficient supervision allows minor errors to become systematic problems [17].

Poor documentation practices: Inaccurate records of cell line provenance, passage number, and culture conditions make it difficult to trace contamination sources once discovered [15].

Failure to implement regular quality control: Without routine screening for contaminants like mycoplasma and bacteria, low-level contamination can persist undetected through multiple experiments [3].

Biological Contaminants

Biological contaminants represent the most diverse and challenging category of laboratory contamination.

Table 2: Biological Contamination Types and Characteristics

| Contaminant Type | Visual Indicators | Impact on Cultures | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Cloudy/turbid media, sudden pH drops, tiny moving granules under microscopy [8] | Rapid culture death, metabolic alterations | Visual inspection, microbial testing, pH monitoring [8] |

| Mycoplasma | No visible signs; may show altered growth rates, morphological changes [17] | Altered gene expression, metabolism, and cellular function [17] | PCR, fluorescence staining, ELISA [17] |

| Fungi/Yeast | Fungal filaments or ovoid/spherical particles; pH usually stable initially then increases [8] | Culture overgrowth, nutrient depletion, metabolic waste | Microscopy, microbial culture [8] |

| Viruses | Typically no visible signs [8] | Altered cellular metabolism, safety concerns for lab personnel | Electron microscopy, immunostaining, ELISA, PCR [8] |

| Cross-Contamination | Unusual morphology or growth characteristics [15] | Misidentification, invalid experimental outcomes | STR profiling, karyotyping, isoenzyme analysis [15] |

Chemical and Physical Contaminants

Chemical contamination: Endotoxins, plasticizers, detergent residues, and impurities in media, sera, and water can alter cellular responses without visible signs [8]. These contaminants may originate from improperly cleaned glassware or extractables from plastic consumables [17].

Particulate contamination: Particularly critical in GMP manufacturing, particles can originate from bioreactor components, tubing degradation, or air filtration systems, potentially affecting product safety and quality [17].

Detection Methodologies and Authentication Protocols

Cell Line Authentication Techniques

Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling STR profiling has become the standard method for intra-species identity testing of human cell lines, operating on the same principle as forensic DNA fingerprinting [15].

Experimental Protocol: STR Profiling

- Extract genomic DNA from cell samples using standard phenol-chloroform or commercial extraction kits

- Amplify multiple polymorphic STR loci simultaneously via PCR using commercial STR profiling kits

- Separate amplified fragments by capillary electrophoresis

- Analyze fragment sizes to determine the number of repeats at each locus

- Compare the resulting profile to reference databases such as the ANSI free-to-use online database containing STR profiles of almost 2,700 human cell lines [15]

- Establish a unique DNA fingerprint for the cell line or identify cross-contamination by profile mismatches

Isoenzyme Analysis This traditional method uses band patterns from the separation of proteins by electrophoresis to detect species-specific differences in enzyme structure and mobility [15].

Experimental Protocol: Isoenzyme Analysis

- Prepare cell lysates from cultured cells using non-denaturing detergents

- Separate intracellular enzymes by electrophoresis on agarose or polyacrylamide gels

- Stain for specific enzyme activities (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, lactate dehydrogenase)

- Analyze banding patterns for species-specific isoforms

- Compare mobility patterns to reference standards for species identification

Karyotyping Cytogenetic analysis examines stained chromosomes to determine genotype stability and identify interspecies contamination [15].

Experimental Protocol: Karyotyping

- Treat exponentially growing cells with colcemid to arrest cells in metaphase

- Harvest cells and subject to hypotonic solution to swell cells and separate chromosomes

- Fix cells in methanol:acetic acid solution

- Drop cell suspension onto slides and stain with Giemsa or other chromosome-specific stains

- Analyze chromosome number, size, and banding patterns under microscopy

- Document any aneuploidy or structural abnormalities characteristic of transformation or cross-contamination

Microbial Contamination Detection

Mycoplasma Detection Protocol

- Culture cells in antibiotic-free medium for at least 3-5 days before testing

- For PCR-based detection: Extract DNA from both cell culture supernatant and cell pellet

- Amplify mycoplasma-specific 16S rRNA gene sequences using genus-specific primers

- Include positive and negative controls in each run

- Alternatively, use fluorescence staining with DNA-binding dyes (e.g., Hoechst 33258) to detect extranuclear DNA in infected cultures

- For cultural methods, inoculate samples into both liquid and solid mycoplasma media

- Incubate for up to 4 weeks with periodic subculturing

- Confirm positive results by PCR or staining if turbidity indicators appear in liquid media [8] [3]

Diagram 1: Laboratory Contamination Pathways from Source to Detection. This workflow illustrates the relationship between contamination sources, types, and appropriate detection methodologies.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Prevention

Implementing a robust contamination control strategy requires specific reagents and materials designed to prevent, detect, and eliminate laboratory contaminants.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Contamination Control

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Notes | Quality Control Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Cell Culture Media | Cell growth and maintenance | Select based on cell type; avoid antibiotics for routine culture | Endotoxin testing, sterility validation, performance qualification [8] |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kits | PCR or fluorescence-based detection | Test every 3-4 weeks; use multiple methods for confirmation | Include positive and negative controls; verify sensitivity [3] |

| STR Profiling Kits | Cell line authentication | Authenticate upon acquisition, before freezing, and every 10 passages | Compare to reference databases; document profiles [15] |

| Sterile Single-Use Consumables | Prevention of cross-contamination | Use pre-sterilized pipettes, flasks, and containers | Certificate of sterilization; particulate testing (GMP) [17] |

| HEPA-Filtered Biosafety Cabinets | Environmental control | Certify every 6-12 months; monitor pressure differentials | Particle counting, airflow velocity testing [19] |

| Validated Cell Banking Systems | Secure cell line preservation | Use controlled-rate freezing; maintain detailed inventory | Viability testing, identity confirmation post-thaw [15] |

Contamination in laboratory settings, particularly cell line cross-contamination, remains a persistent challenge with far-reaching consequences for research integrity and drug development. The errors and lapses that enable contamination span from technical mistakes in basic cell culture practice to systematic failures in laboratory quality management. Implementation of rigorous authentication protocols like STR profiling, routine contaminant screening, and adherence to good cell culture practices represents a minimal standard for credible research. As the scientific community increasingly recognizes these challenges, authentication is becoming conditional for grant funding and publication in leading journals [15]. By understanding how contamination happens and implementing the detection and prevention strategies outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly reduce contamination risks, enhance data reproducibility, and advance more reliable scientific discovery.

Cross-contamination of cell lines is a critical and persistent challenge in biomedical research and biopharmaceutical manufacturing. This issue, which includes the misidentification of cell lines and contamination with microorganisms, compromises the very foundation of scientific inquiry. The consequences extend far beyond the laboratory, affecting the validity of published research, imposing massive financial losses, and ultimately hindering the development of safe and effective patient therapies [20] [17]. This whitepaper details the scientific, financial, and therapeutic repercussions of cell line cross-contamination and outlines essential mitigation strategies for the research community.

Scientific Consequences: Compromised Data and Lost Reproducibility

The use of contaminated or misidentified cell lines fundamentally undermines scientific integrity, leading to publication of irreproducible data and misleading conclusions.

Misidentified and Cross-Contaminated Cell Lines

Cell line misidentification occurs when a culture is inadvertently replaced by or mixed with another, more aggressive cell line. Studies estimate that between 18% and 36% of cell lines are contaminated or misidentified [20]. The pervasive nature of this problem is staggering; an analysis suggests that up to 20% of published papers could be invalid due to the use of misidentified or cross-contaminated cell lines [21]. This invalidates entire bodies of literature, wasting scientific effort and misdirecting future research.

Microbial and Viral Contamination

Beyond cross-contamination with other cell lines, microbial adversaries present a constant threat. These contaminants can overtly destroy cultures or, more insidiously, alter cell behavior without obvious signs.

- Mycoplasma: This bacterium lacks a cell wall and is not detected by routine microscopy. It alters gene expression, metabolism, and cellular function, leading to misleading experimental results [17].

- Viruses: Viral contamination can be introduced through contaminated raw materials like serum or the host cell lines themselves. Viruses such as Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) and Ovine Herpesvirus 2 (OvHV-2) can reside latently in cells, posing a risk to both research integrity and the safety of biological products [22]. Notably, Mycoplasma and certain viruses are small and flexible enough to penetrate the 0.2 micron filters traditionally used to sterilize cell culture media, necessitating more stringent 0.1 micron filtration [23].

Table 1: Common Types of Cell Culture Contamination and Their Impacts

| Contaminant Type | Common Examples | Key Effects on Cell Culture | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Contaminated Cell Lines | HeLa, HEK293 overgrowth | Misidentified culture genotype/phenotype; non-representative data [17] | STR Profiling [21] |

| Mycoplasma | A. laidlawii, numerous other species | Altered metabolism, gene expression, and cell function; no turbidity [17] | PCR, fluorescence assays, bioluminescence [17] [21] |

| Viral | Vesivirus 2117, Mouse Minute Virus (MMV), EBV, OvHV-2 | Altered cellular metabolism; cytopathic effects (cell rounding, lysis); product safety risk [22] [24] | PCR, infectivity assays, in vitro/vivo tests [22] [24] |

| Bacterial & Fungal | Various bacteria, yeast, mold | Rapid pH shifts, turbid media, cell death; visible filaments [17] | Microscopy, microbial culture |

Financial Consequences: The Multimillion-Dollar Toll

Cross-contamination incidents inflict severe economic losses across the research and development pipeline, from academic grants to commercial biomanufacturing.

Impact on Research and Development

The use of contaminated cell lines wastes scarce research resources. It leads to futile experiments, invalidates pre-clinical data, and requires costly repetition of work. The cumulative cost of published research that is later invalidated has been estimated in the billions of dollars globally when factoring in grants, personnel time, and materials [20].

Impact on Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing

In commercial production, the financial impact is even more acute. A single viral contamination event in a large-scale bioreactor can halt production for months, resulting in:

- Direct Losses: Loss of the product batch, costs of decontamination, and facility downtime [23] [24].

- Indirect Costs: Stock devaluations, regulatory fines, and costly product recalls [24]. For context, the FDA issues an average of 1,279 drug recalls annually, many due to contamination issues [25]. The 2009 contamination of Genzyme's mammalian cell culture bioreactors with Vesivirus 2117 is a landmark case. It led to a plant shutdown, critical drug shortages, and an estimated $300 million in lost revenue, starkly illustrating the massive financial risk [24].

Table 2: Financial and Therapeutic Impacts of Major Contamination Events

| Event / Contaminant | Financial Impact | Therapeutic Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Vesivirus 2117 in CHO Cells [24] | ~$300 million in lost revenue; plant shutdown | Shortages of life-saving drugs (e.g., enzyme replacements for genetic disorders) |

| Mycoplasma Contamination [23] | Major costs from batch loss, decontamination, and production delays | Compromised quality and safety of biologics; risk of contaminated products reaching patients |

| Particle Contamination (GMP) [17] | Batch rejection, regulatory action, and product recalls | Risk of immune reactions or emboli in patients receiving injectable biologics |

Therapeutic Consequences: The Ultimate Patient Impact

When research data is flawed or manufacturing is compromised, the development and supply of patient therapies are directly threatened.

Delays in Drug Development and Diminished Efficacy

Invalid pre-clinical research misdirects drug development programs. Therapies that show promise in contaminated or misidentified cell models may fail in later, more costly animal or human trials, delaying the arrival of effective treatments to patients by years [20]. Furthermore, contaminants like mycoplasma can alter a cell's response to a drug candidate, leading to false negatives or false positives in screening assays [17].

Direct Risks to Patient Safety

The most severe consequence is the direct risk to patient safety.

- Adverse Events: Contaminated pharmaceutical products can cause serious adverse reactions, treatment failures, or allergic responses [25] [26]. Adverse drug events cause approximately 1.3 million emergency department visits annually in the U.S. [25].

- Product Recalls and Shortages: Contamination events trigger recalls, depriving patients of essential medicines. The Genzyme virus contamination caused severe shortages of drugs for patients with genetic disorders like Gaucher's and Fabry's diseases, creating a public health crisis [24].

Mitigation Strategies: A Scientist's Toolkit

Preventing cross-contamination requires a multi-faceted approach combining rigorous protocols, advanced technologies, and a culture of quality.

Figure 1: A workflow for maintaining cell line integrity, from initial acquisition to ongoing culture.

Essential Research Reagents and Protocols

The following tools and methods are critical for ensuring cell line authenticity and sterility.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Methods for Contamination Prevention

| Tool / Method | Function | Key Protocol Details |

|---|---|---|

| STR Profiling [21] | Cell line authentication via DNA fingerprinting. | Amplify 10+ short tandem repeat loci by PCR; compare resulting profile to reference database. A mismatch indicates misidentification. |

| Mycoplasma Detection [17] [21] | Detects viable mycoplasma contamination. | PCR: Amplifies mycoplasma DNA. Bioluminescence Assay: Detects mycoplasma enzyme activity (converts ADP to ATP, measured via luciferase). |

| Viral Screening [22] [24] | Identifies latent or active viral infections. | Use PCR with virus-specific primers. Also, in vitro infectivity assays on permissive cell lines to detect cytopathic effects. |

| 0.1 Micron Filtration [23] | Removes mycoplasma & small viruses from media. | Filter cell culture media through 0.1µ membrane instead of standard 0.2µ to retain small, flexible contaminants. |

| Closed Bioprocessing Systems [17] | Single-use equipment to prevent carry-over contamination. | Use disposable bioreactor bags, tubing, and connectors to eliminate cleaning validation and cross-contact between batches. |

A Proactive Culture of Prevention

Ultimately, technical solutions must be supported by institutional commitment.

- Training and Adherence to Aseptic Technique: Comprehensive training for all personnel is the first line of defense [17] [27].

- Cell Line Authentication: Journals and funding agencies increasingly require STR profiling of human cell lines prior to publication or grant approval [21].

- Routine Quality Control: Implement scheduled, periodic testing for mycoplasma and other contaminants [17].

- Facility Design: Employ closed processing systems, HEPA-filtered cleanrooms, and strict gowning procedures to control the environment [17] [27].

Figure 2: The cascading consequences of cell line cross-contamination, showing how a single laboratory issue leads to broad societal impacts.

The real-world cost of cell line cross-contamination is unacceptably high, manifesting as scientific fallacies, immense financial waste, and tangible patient harm. The tools and methodologies to prevent these consequences—STR profiling, rigorous microbial testing, and quality-controlled culture practices—are readily available. The scientific community must universally adopt these practices as a non-negotiable standard. By doing so, researchers and manufacturers can protect the integrity of their work, safeguard public health, and ensure that resources are dedicated to developing genuine therapeutic breakthroughs.

Authenticating Your Cells: A Practical Guide to Methods and Techniques

The Critical Problem of Cell Line Misidentification in Biomedical Research

The use of misidentified and cross-contaminated cell lines represents a pervasive threat to scientific reproducibility and research integrity. Interspecies and intraspecies cross-contamination among cultured cell lines is a persistent problem, with reported frequencies ranging from 6% to as high as 100% in some collections [28]. Current analyses reveal that at least 5% of human cell lines used in manuscripts submitted for peer review are misidentified, leading to approximately 4% of manuscripts being rejected for severe cell line problems [29]. The financial impact is staggering: estimates indicate roughly $990 million were spent to publish 9,894 manuscripts using just two known HeLa-contaminated cell lines (HEp-2 and Intestine 407) [29]. With 531 misidentified cell lines currently documented in the International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC) register, the total economic damage likely amounts to billions of research dollars worldwide [29].

The historical roots of this problem trace back to 1968, when Stanley Gartler demonstrated that 18 extensively used cell lines were actually derived from HeLa cells [28]. Today, the Cellosaurus database lists at least 209 misidentified cell lines that have been shown to be HeLa [28]. More recent studies continue to uncover cross-contaminated cell lines purportedly representing various cancers, including breast, prostate, thyroid, and esophagus malignancies [28]. This widespread misidentification persists primarily due to mishandling and inattention to best practices in tissue culture, compounded by the fact that less than half of researchers regularly verify their cell lines using standard authentication techniques [28] [30].

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Cell Line Misidentification

| Aspect of Impact | Documented Evidence | Scale/Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 5% of submitted manuscripts contain misidentified lines [29] | 4% manuscript rejection rate for severe cell line problems [29] |

| Financial Cost | Studies on two HeLa-contaminated lines [29] | ~$990 million on 9,894 papers [29] |

| Historical Context | 209 cell lines in Cellosaurus misidentified as HeLa [28] | First documented in 1968; persists despite awareness [28] |

| Geographic Variation | Cell lines established in China [29] | 85.5% misidentification rate (59 of 69 lines) [29] |

Fundamentals of STR Genotyping Technology

Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling, also known as DNA fingerprinting, has emerged as the international reference standard for human cell line authentication [29]. STRs are short DNA sequences of 1-6 base pairs that are repeated in tandem and distributed throughout the human genome [28]. These hypervariable regions constitute approximately 3% of the human genome and serve as hotspots for homologous recombination events that maintain their variability [28] [31]. The core innovation of STR profiling lies in its ability to create a unique genetic profile for each human cell line derived from a single donor by examining the length variations at multiple STR loci [28].

The technology leverages the fact that STR loci contain highly polymorphic regions with many different sequence variants in human populations [28]. The most commonly used human STR loci consist of tetranucleotide repeats (e.g., GATA), though some kits include pentanucleotide repeats [28]. The resulting PCR products typically differ by units of four base pair repeats, with alleles simply designated by whole numbers representing the number of repeats [28]. Microvariants containing partial repeats due to insertions or deletions are designated with decimal notations (e.g., 8.1, 8.2, 8.3) [28].

The exceptional discriminatory power of STR profiling stems from examining multiple loci simultaneously. Early systems utilized 8 STR loci, but current standards recommend 13-26 different STR loci for authentication [28] [32]. The probability of two unrelated individuals having identical profiles at 10 STR loci is exceptionally low, with random match probabilities reaching 1 in 2.92 × 10⁹ [30]. This high discrimination power, combined with standardization and reproducibility, has established STR profiling as the "gold standard" for cell line authentication [29] [32].

Standardized STR Profiling Methodologies and Protocols

The STR genotyping process follows a well-established workflow that begins with DNA extraction from cell line samples. The ANSI/ATCC ASN-0002 standard, recently revised in 2022, provides comprehensive guidance on DNA extraction, STR profiling, data analysis, quality control, and interpretation of STR results [33] [32]. This standard recommends profiling be performed more frequently than every three years and whenever phenotypic changes are noted in culture [32].

The core methodology involves several critical steps. First, PCR primers are designed to amplify each selected STR locus so alleles are distinguishable by size, with one primer of each pair labeled with a fluorescent dye [28]. Multiplex PCR allows simultaneous amplification of multiple STR loci (typically 16-26) in a single reaction by using different fluorescent dyes and designing amplicon size ranges so they don't overlap [28]. Modern capillary instruments can separate up to eight different dyes spectrographically, allowing analysis of 3-5 STR loci per dye [28].

Following amplification, capillary electrophoresis enables length determination of STR PCR products with approximately 0.5 nucleotide accuracy by comparison with an internal size standard [28]. Comparing STR allele length to an allelic ladder allows for accurate allele call determination based on the actual number of repeats [28]. The ANSI/ATCC standard specifically recommends 13 core autosomal STR loci as a minimum standard for authentication: CSF1PO, D3S1358, D5S818, D7S820, D8S1179, D13S317, D16S539, D18S51, D21S11, FGA, TH01, TPOX, and vWA [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Commercial STR Profiling Systems

| Specification | GlobalFiler PCR Amplification Kit | Identifiler Plus PCR Amplification Kit | PowerPlex 1.2 System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Markers | 24 (21 autosomal + 3 sex determination) | 16 (15 autosomal + amelogenin) | 8 STR loci + amelogenin |

| Dye Chemistry | 6-dye (FAM, VIC, NED, TAZ, LIZ, SID) | 5-dye (FAM, VIC, NED, PET, LIZ) | Not specified |

| Amplicon Size Range | ≤400 bp (SE33 <450 bp) | ≤360 bp | Not specified |

| Amplification Time | <90 minutes | 2.5-3 hours | Not specified |

| Random Match Probability | Not specified | Not specified | 1 in 2.92 × 10⁹ [30] |

For data interpretation, two main algorithms are commonly employed. The Tanabe algorithm considers profiles related with 90-100% similarity, ambiguous at 80-90%, and unrelated below 80% [34]. The Masters algorithm is slightly more lenient, considering profiles related at ≥80% similarity, mixed/uncertain at 60-80%, and unrelated below 60% [34]. These differences stem from their distinct calculation methods: Tanabe multiplies shared alleles by two then divides by the total alleles in both profiles, while Masters divides shared alleles by the total alleles in the query profile only [34].

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methodological Innovations

STR profiling technology continues to evolve with applications extending beyond basic cell line authentication. Recent research demonstrates the innovative use of forensic STR markers containing 23 loci for authenticating human cell lines stored over 34 years, confirming the efficacy of long-term cryopreservation and genetic stability [34]. This approach represents one of the most extensive single-laboratory investigations into cell line preservation using forensic-grade tools [34].

Methodological advancements are addressing persistent challenges in STR analysis, particularly for low-template DNA (LT-DNA) or low copy number (LCN) DNA samples. Traditional STR analysis of limited DNA templates faces issues including higher stutter rates and heterozygous imbalance due to stochastic effects during sampling and PCR amplification [35]. Novel approaches like abasic-site-mediated semi-linear preamplification (abSLA PCR) significantly enhance allele recovery from trace DNA by minimizing error accumulation through strategic modification of amplification patterns [35].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms offer promising alternatives for STR profiling, though technical challenges remain. STRs sequenced with PCR-free protocols demonstrate up to ninefold fewer errors than those sequenced with PCR-containing protocols [31]. Bioinformatics tools like STR-FM (Short Tandem Repeat profiling using Flank-based Mapping) can detect the full spectrum of STR alleles from short-read data and adapt to emerging read-mapping algorithms [31]. This pipeline is particularly valuable for heterogeneous genetic samples such as tumors, viruses, and organelle genomes [31].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for STR Profiling

Successful implementation of STR profiling requires specific research reagents and materials. Commercial STR profiling kits provide standardized, optimized solutions for cell line authentication. The Promega PowerPlex systems (including PowerPlex 1.2 and PowerPlex 18D) have become gold standard tools used by cell culture facilities worldwide [30] [5]. These systems typically include reagents for multiplex PCR amplification of STR loci, with the Cell ID System simultaneously amplifying ten loci (nine STR loci plus amelogenin for gender identification) [30].

Thermo Fisher Scientific offers multiple STR kit options, including the GlobalFiler PCR Amplification Kit (24 loci), Identifiler Plus PCR Amplification Kit (16 loci), and Identifiler Direct PCR Amplification Kit [32]. These kits vary in their marker sets, dye chemistries, amplification times, and sample input requirements, allowing researchers to select based on their specific needs [32].

Specialized reagents address particular methodological challenges. The SiFaSTR 23-plex system incorporates 21 autosomal STRs and two sex-related polymorphisms, providing forensic-level discrimination power for research applications [34]. For low-template DNA, specialized polymerases and amplification strategies like the abSLA PCR method enhance sensitivity while maintaining accuracy [35].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for STR Profiling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial STR Kits | Promega PowerPlex systems, Thermo Fisher Identifiler and GlobalFiler kits [30] [32] | Standardized multiplex PCR amplification of STR loci with fluorescent detection |

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [34], QIAamp DNA Investigator kit [35] | High-quality DNA extraction from cell line samples |

| Specialized Systems | SiFaSTR 23-plex system [34] | Forensic-grade STR profiling with expanded marker sets |

| Enhanced Polymerases | Phusion Plus DNA Polymerase, PrimeSTAR GXL DNA Polymerase [35] | Improved amplification efficiency, especially for challenging templates |

| Analysis Software | GeneMapper Software, microsatellite analysis (MSA) software [32] | STR fragment analysis and allele calling |

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices for Research Laboratories

Effective cell line authentication requires integrating STR profiling into routine laboratory practice. Leading repositories like ATCC recommend comprehensive testing regimens that include morphology checks, growth curve analysis, species verification, mycoplasma detection, and STR-based identity verification [5]. STR profiling should be performed upon receipt of new cell lines, at regular intervals during maintenance (more frequently than every three years), before freezing down stocks, and when phenotypic changes are observed [32] [5].

Best practices emphasize using low-passage cell lines to minimize genetic drift and phenotypic changes associated with excessive subculturing [5]. Researchers should record passage numbers and establish predetermined ranges for experimental use [5]. When publishing research, the materials and methods section should include the cell line designation, repository catalog number (if applicable), and passage numbers under which experiments were conducted [5].

Database resources are crucial for effective authentication. The Cellosaurus database provides information on more than 102,000 human cell lines and contains STR profiles for more than 8,000 distinct human cell lines [29]. The CLASTR (Cellosaurus STR similarity search tool) enables researchers to compare obtained STR profiles with those in the Cellosaurus database [29]. These resources, combined with the ICLAC register of misidentified cell lines, provide essential reference data for proper authentication [29].

The scientific community increasingly mandates authentication, with many journals now requiring STR profiling data for manuscripts reporting cell line research [29] [32]. Funding agencies also increasingly expect verification of cell line identity in grant applications [30]. This multi-layered approach—combining regular laboratory testing, database consultation, and journal requirements—represents the most effective strategy for addressing the persistent problem of cell line misidentification and ensuring research reproducibility and reliability [29].

Cell culture serves as a cornerstone for advancements in biomedical research, drug discovery, and biotherapeutic production. However, the integrity of this research is fundamentally threatened by the persistent challenge of cell line cross-contamination and misidentification. It is estimated that 18-36% of all actively growing cell line cultures are misidentified or cross-contaminated, leading to invalid data, wasted resources, and irreproducible findings [36]. The International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC) registry currently lists nearly 600 misidentified or contaminated cell lines, a figure that underscores the scale of this problem [11]. Within this context of safeguarding research integrity, traditional tools like isoenzyme analysis and karyotyping have played, and continue to play, critical roles in cell line authentication and quality control. These techniques provide essential frontline defense by confirming species origin and detecting gross genomic abnormalities, thereby ensuring that experimental results are derived from the intended biological system.

The Critical Problem of Cell Line Cross-Contamination

Cell line cross-contamination occurs when an unintended cell line is introduced into a culture, often through laboratory handling errors or the use of shared reagents. Once introduced, fast-growing cell lines can overtake a slower-growing culture in just a few passages [37]. The most infamous example is HeLa cell contamination; due to its prolific growth, HeLa has contaminated numerous cell lines purportedly representing other tissues, such as liver, stomach, and lung [11]. A comprehensive screen of the ICLAC registry identified 21 misidentified "liver cell lines" and 14 misidentified "stomach cell lines," with lines like QGY-7703, BGC-823, and L-02 all being revealed as HeLa derivatives [11]. A literature search for just five of these misidentified liver cell lines identified almost 6,000 publications that have potentially used contaminated cells, illustrating the ripple effect of invalidated data [11].

The consequences are profound. Research built on misidentified cells generates misleading evidence on disease mechanisms, drug responses, and gene regulation, which in turn compromises evidence-based conclusions and drug development pipelines. Journals and funding agencies are increasingly mandating authentication practices, yet a survey found that only 33% of researchers authenticate their cell lines, and 35% obtain lines from other laboratories rather than certified repositories, perpetuating the risk [36].

Isoenzyme Analysis: A Robust Method for Species Authentication

Isoenzyme analysis is a traditional, yet robust, technique primarily used for verifying the species origin of cell lines and detecting interspecies cross-contamination. Its technical simplicity, reliability, and speed have made it a staple in cell bank characterization and quality control.

Principles and Methodology

The method exploits the fact that the structure and electrophoretic mobility of intracellular enzymes (isoenzymes) vary between species. By comparing the banding patterns of specific enzymes from a test cell extract against known standards, the species of origin can be accurately determined [37]. The process for a typical isoenzyme analysis experiment using a commercial kit involves several key steps, which are visualized in the workflow below.

A standard assay evaluates a panel of enzymes, which typically includes [37]:

- Nucleoside phosphorylase (NP)

- Malate dehydrogenase (MD)

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LD)

- Peptidase B (PepB)

- Aspartate amino transferase (AST)

- Mannose 6-phosphate isomerase (MPI)

For the assay to be considered valid, the corrected migration distance for the system suitability control (e.g., HeLa extract) must not deviate by more than 2 mm from the expected distance provided by the kit manufacturer [37].

Application in Detecting Cross-Contamination

Isoenzyme analysis is particularly effective for identifying interspecies contamination. Its sensitivity allows for detection when a contaminating cell line represents about 10% of the total cell population [37]. The choice of enzyme is critical for detecting specific contaminant pairs, as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Optimal Enzyme Selection for Detecting Specific Cross-Contaminations via Isoenzyme Analysis

| Contaminating Cell Mixture | Most Discriminatory Enzyme(s) |

|---|---|

| Chinese Hamster & Mouse | Peptidase B (PepB) |

| Human & Cercopithecus Monkey | Aspartate Amino Transferase (AST) |

| Chinese Hamster & Human | Lactate Dehydrogenase (LD) |

For instance, while Lactate Dehydrogenase (LD) is useful for detecting human and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell mixtures, it is not reliable for distinguishing between mouse and Chinese hamster cells; for that specific pair, PepB is the definitive enzyme [37]. The technique has successfully identified real-world contaminations, such as a slow-growing human diploid cell line (MRC-5) contaminated with fast-growing Vero cells (cercopithecus monkey), which was apparent from an additional band on the AST gel [37].

Karyotyping: Visualizing Genomic Integrity

Karyotyping is a cytogenetic technique that provides a visual map of the chromosomes within a cell. It is used to confirm the identity of a cell line at the chromosomal level and to detect gross genetic abnormalities that may arise during long-term culture.

Principles and Traditional G-Banding Protocol

The classical method for karyotyping is chromosome G-banding (Giemsa banding). This technique involves staining condensed chromosomes during the metaphase stage of cell division to produce a unique pattern of light and dark bands for each chromosome type. These patterns allow for the identification of numerical abnormalities (e.g., aneuploidy) and structural aberrations, such as translocations, deletions, and inversions [38] [39]. The standard protocol for G-banding karyotype analysis is a multi-day process, as detailed below.

For peripheral blood lymphocytes, a common starting material, the process begins with a 72-hour culture in the presence of a mitogen like phytohemagglutinin to stimulate division [40]. A critical step is the addition of colchicine (or Colcemid) to the culture, which inhibits mitotic spindle formation and arrests cells in metaphase, the stage where chromosomes are most condensed and visible [38] [40]. Subsequent hypotonic treatment (e.g., with 0.075M KCl) swells the cells, spreading the chromosomes apart. Cells are then fixed, typically with a methanol-acetic acid solution, and dropped onto slides [38] [40]. The slides are treated with trypsin and stained with Giemsa to produce the characteristic banding patterns before being analyzed under a microscope to count chromosomes and assess their structure [38] [40].

Capabilities and Limitations of Traditional Karyotyping

Traditional G-banding karyotyping is a powerful whole-genome technique that can detect balanced and unbalanced chromosomal abnormalities. It has been instrumental in clinical diagnostics, such as characterizing chromosomal disorders like Turner syndrome, where it can differentiate between X monosomy (45,X) and mosaic or structural X abnormalities [41]. However, its resolution is limited to 5-10 Megabases (Mb), meaning it can only detect relatively large-scale genetic changes [39]. Furthermore, it is a low-throughput, time-consuming technique that requires skilled technicians and can take 3-4 weeks from culture to result [39].

Comparative Analysis: Techniques and Applications

While both isoenzyme analysis and karyotyping are traditional authentication tools, their applications, strengths, and weaknesses are distinct. The following table provides a direct comparison of these two techniques with a modern authentication method.

Table 2: Comparison of Cell Line Authentication and Characterization Techniques

| Feature | Isoenzyme Analysis | Karyotyping (G-Banding) | Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Species authentication | Detection of gross chromosomal abnormalities | Intraspecies human cell line identification |

| Key Advantage | Rapid, cost-effective, technically simple | Detects balanced structural rearrangements | High precision, "fingerprint" unique to donor |

| Principal Limitation | Cannot differentiate between cell lines of the same species | Low resolution (5-10 Mb), time-consuming | Not suitable for non-human cells or detecting species cross-contamination |

| Typical Turnaround Time | Hours to a day [37] | 3-4 weeks [39] | Days to a week |

| Detection Sensitivity for Contaminants | ~10% of total population [37] | Varies; generally low for mosaicism | Very high (sensitive to low-level contaminants) |

This comparison highlights the complementary nature of these tools. Isoenzyme analysis is a first-line defense for ensuring species purity, while karyotyping monitors genomic stability. For the definitive authentication of human cell lines, STR profiling is now considered the gold standard, as it can uniquely identify a specific cell line based on the donor's genetic profile, much like a DNA fingerprint [36].

Modern Context and Evolving Methodologies

The principles of isoenzyme analysis and karyotyping remain relevant, but the technologies have evolved. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) has been explored as an automated alternative for rapid isoenzyme profiling [42]. In karyotyping, traditional G-banding has been supplemented or replaced by higher-resolution molecular techniques.

Table 3: Evolution of Karyotyping Methodologies

| Method | Resolution | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-Banding | 5-10 Mb [39] | Low cost; detects balanced rearrangements | Low resolution; requires metaphase cells |

| Array-Based Karyotyping | 1-2 Mb [39] | Automated; whole-genome coverage | Cannot detect balanced abnormalities |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | 1 base pair [39] | Extremely high resolution | High cost; complex data analysis |

| Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) | Targeted hotspots [39] | High sensitivity and precision for specific targets | Not a whole-genome screen |

These advanced methods, such as array-based karyotyping and ddPCR, offer improved resolution and throughput for detecting sub-chromosomal abnormalities common in cultured cells, such as the 20q11.21 amplification found in over 20% of human pluripotent stem cell lines [39].

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful authentication strategy relies on specific reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential solutions for implementing these traditional and modern techniques.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Line Authentication

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AuthentiKit System | Isoenzyme analysis for species ID | Speciation and detection of interspecies cross-contamination in cell banks [37]. |

| KaryoMAX Colcemid | Mitotic inhibitor for karyotyping | Arresting cells in metaphase for chromosome preparation [40]. |

| Giemsa Stain | Chromosome banding for G-banding | Creating unique banding patterns for chromosome identification [38] [40]. |

| STR Profiling Kits | Human cell line authentication | Generating a unique DNA fingerprint to confirm cell line identity against reference databases [36]. |

| PCR/KaryoStat+ Array | Array-based karyotyping | Detecting copy number variations in cell banks with >1 Mb resolution [39]. |

Isoenzyme analysis and karyotyping remain foundational tools in the rigorous quality control of cell cultures. Isoenzyme analysis provides a swift and reliable method for confirming species identity and flagging interspecies contamination, while karyotyping offers a cytogenetic window into the genomic stability of a cell line. Although modern techniques like STR profiling and array-based karyotyping offer greater resolution and precision for specific tasks, the traditional methods provide a critical first line of defense. In an era where an estimated tens of thousands of studies may be based on misidentified cells, integrating these tools into a routine authentication protocol—using available resources like ICLAC and Cellosaurus—is not just best practice but an ethical imperative for ensuring the validity and reproducibility of biomedical research [11].

Navigating Authentication Services and Reference Databases

Cross-contamination and misidentification of cell lines constitute a pervasive and persistent challenge in biomedical research, with significant consequences for data integrity and scientific reproducibility. It is estimated that 15–20% of cell lines currently in use may not be what they are documented and reported to be, a problem that has persisted for more than six decades since the first observations of vigorous lines like HeLa overgrowing slower-growing cultures [43]. The seriousness of this issue is underscored by analyses revealing that many cell lines used in specific fields, such as thyroid cancer research, have been cross-contaminated with lines from other tissues and used for decades prior to discovery [43]. This widespread problem jeopardizes research outcomes, wastes valuable resources, and undermines the validity of scientific publications, necessitating robust authentication services and reference databases as essential components of rigorous scientific practice.

Cell Line Authentication Methods

Established Authentication Techniques

Several analytical techniques have been developed and refined for verifying cell line identity, each with distinct applications, advantages, and limitations:

Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling: This method has emerged as the international gold standard for intra-species authentication of human cell lines [43] [44]. STR profiling measures the exact number of repeating nucleotides at specific loci in the genome, creating a unique genetic fingerprint for each cell line. The technique works on the same principle as forensic DNA fingerprinting but has evolved from labor-intensive Southern blotting to rapid, higher-throughput PCR-based methods that simultaneously amplify multiple polymorphic STR loci [43]. The probability of two unrelated cell lines sharing an identical STR profile is exceptionally low, with random match probabilities approximately 1 in 1.83×10^17 when using 15 autosomal loci [45].

Isoenzyme Analysis: One of the earlier methods developed, isoenzyme analysis uses band patterns from electrophoretic separation to detect species-specific differences in the structure and mobility of intracellular enzymes [43]. While easily performed, robust, and returning rapid results, this technique can be subject to low reproducibility compared to DNA-based methods [43].

Karyotyping: This traditional cytogenetic approach involves the examination of stained chromosomes to determine whether the genotype of a cell line is stable [43]. Some cell repositories still perform karyotyping routinely, as it can reveal significant genetic alterations that may occur during extended culture periods.