Cross-Species Cell Annotation Foundation Models: A New Paradigm for Decoding Evolutionary Biology and Disease

Cross-species cell annotation foundation models represent a transformative advance in single-cell biology, enabling the deciphering of universal gene regulatory mechanisms across evolution. This article explores how AI models like GeneCompass, TranscriptFormer, and CAME leverage vast datasets from multiple species to accurately identify cell types, predict disease states, and simulate cellular behavior. We examine the foundational principles, methodological architectures, optimization strategies, and validation frameworks that underpin these tools. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides critical insights for applying these models to translate findings from model organisms to human biology, accelerating the discovery of disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets.

Cross-Species Cell Annotation Foundation Models: A New Paradigm for Decoding Evolutionary Biology and Disease

Abstract

Cross-species cell annotation foundation models represent a transformative advance in single-cell biology, enabling the deciphering of universal gene regulatory mechanisms across evolution. This article explores how AI models like GeneCompass, TranscriptFormer, and CAME leverage vast datasets from multiple species to accurately identify cell types, predict disease states, and simulate cellular behavior. We examine the foundational principles, methodological architectures, optimization strategies, and validation frameworks that underpin these tools. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides critical insights for applying these models to translate findings from model organisms to human biology, accelerating the discovery of disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets.

The Evolutionary Imperative: Why Cross-Species Cell Annotation is Revolutionizing Biology

Defining Cross-Species Cell Annotation Foundation Models

Cross-species cell annotation represents a computational frontier in evolutionary biology and translational research, enabling the transfer of cellular knowledge from model organisms to humans. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has generated massive cellular atlases across diverse species, creating an unprecedented opportunity to decipher conserved and divergent cellular programs [1] [2]. Foundation models (FMs), pre-trained on millions of cells through self-supervised learning, have emerged as powerful tools to address the fundamental challenge of cross-species annotation: reconciling genomic differences to identify homologous cell types across evolutionary distances [3] [4] [5]. These models transform single-cell transcriptomics by treating cells as "sentences" and genes as "words," learning deep biological representations that transcend species boundaries through sophisticated architectural innovations [4]. This protocol examines the defining architectures, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation of cross-species cell annotation foundation models, providing researchers with a framework for leveraging these transformative tools in evolutionary biology and drug development.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Model Performance

Comprehensive evaluation of cross-species annotation models reveals distinct performance advantages across different biological contexts and evolutionary distances. The table below synthesizes key quantitative findings from major benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Cross-Species Cell Annotation Methods

| Model | Core Approach | Test Scenarios | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAME [1] | Heterogeneous graph neural network | 54 scRNA-seq datasets across 7 species; 649 species pairs | Significant improvement in cell-type assignment across distant species; 6.26% average accuracy drop when excluding non-one-to-one homologies | Utilizes non-one-to-one homologous gene mapping; robust to sequencing depth inconsistencies |

| SATURN [2] | Protein language model (ESM-2) with macrogene space | Mammalian cell atlas (335k cells); frog-zebrafish embryogenesis | Effective annotation transfer across evolutionarily remote species; identification of misannotated cell populations | Discovers functionally related gene groups; enables cross-species differential expression analysis |

| Icebear [6] | Neural network decomposition of cell identity, species, and batch factors | Mouse-chicken-opossum brain/heart sci-RNA-seq3 | Accurate cross-species prediction of single-cell profiles; reveals X-chromosome upregulation evolutionary patterns | Enables single-cell resolution comparison without cell type matching; predicts missing biological contexts |

| Nicheformer [3] | Transformer trained on dissociated and spatial data (110M cells) | Spatial composition prediction; spatial label prediction | Outperforms Geneformer, scGPT, UCE, and CellPLM on spatial tasks | Integrates spatial context; transfers spatial information to dissociated data |

| scFMs (General) [5] | Various transformer architectures pretrained on large single-cell corpora | 5 datasets with diverse biological conditions; 7 cancer types | Robust and versatile across tasks; no single model dominates all scenarios | Captures biological insights into relational structure of genes and cells |

Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that foundation models exhibit particular strengths in capturing biological relationships. A comprehensive evaluation of six scFMs against traditional baselines revealed that while these models are robust and versatile tools for diverse applications, simpler machine learning models can be more efficient for specific datasets under resource constraints [5]. Notably, no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, emphasizing the importance of task-specific model selection.

Table 2: Performance Across Cell-Level Tasks in Realistic Conditions

| Task Category | Top Performing Models | Key Findings | Considerations for Cross-Species Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Annotation [5] | scGPT, Geneformer, UCE | >80-90% accuracy for major cell types; struggles with rare cell types | Model performance correlates with cell-property landscape roughness in latent space |

| Cross-Species Transfer [1] [2] | CAME, SATURN | Effective even for non-model species and evolutionarily remote pairs | Dependency on quality of homologous gene mapping or protein embeddings |

| Spatial Context Prediction [3] | Nicheformer | Systematically outperforms models trained only on dissociated data | Requires spatial transcriptomics data for training; enables tissue niche prediction |

| Clinical Prediction [5] | scGPT, scFoundation | Accurate cancer cell identification and drug sensitivity prediction in zero-shot settings | Potential for translating findings from model organisms to human clinical contexts |

Methodological Approaches for Cross-Species Annotation

Homology-Aware Graph Neural Networks (CAME)

The CAME framework employs a heterogeneous graph neural network architecture that explicitly incorporates both one-to-one and non-one-to-one homologous gene mappings, which is particularly crucial for distant species comparisons where up to 60-75% of highly informative genes may not have one-to-one homologs [1].

Experimental Protocol:

Input Processing:

- Prepare scRNA-seq count matrices from reference (labeled) and query (unlabeled) species

- Compile homologous gene mappings, including one-to-many and many-to-many relationships

- Construct single-cell networks using k-nearest-neighbors (KNN) within each species

Graph Construction:

- Create a heterogeneous graph with two node types (cells and genes)

- Establish cell-gene edges for non-zero expression relationships

- Create gene-gene edges based on homology mappings

- Incorporate precomputed cell-cell edges from KNN networks

Model Architecture:

- Implement parameter-sharing graph convolution layers for heterogeneous nodes and edges

- Employ heterogeneous graph attention mechanism for cell-type classification

- Utilize multi-label classification to handle hierarchical cell types and multiple correspondences

Training Protocol:

- Optimize combined multiclass and multilabel cross-entropy loss via backpropagation

- Train for 200-300 epochs until convergence

- Use Adjusted Mutual Information (AMI) with preclustered query cells to select checkpoints

Output Interpretation:

- Extract cell-type assignment probabilities for query cells

- Identify unresolved cell states through low-confidence assignments

- Generate aligned cell and gene embeddings for joint visualization

- Perform cross-species gene module extraction

Protein Language Model Integration (SATURN)

SATURN introduces a novel approach that couples gene expression with protein embeddings from large language models (e.g., ESM-2) to create universal cell embeddings that transcend genomic differences between species [2].

Experimental Protocol:

Input Preparation:

- Obtain scRNA-seq count matrices from multiple species

- Generate protein embeddings using ESM-2 for all genes

- Acquire initial within-species cell annotations (cell-type assignments or clustering results)

Macrogene Space Construction:

- Learn a shared macrogene space representing functionally related gene groups

- Define gene-to-macrogene importance weights based on protein embedding similarities

- Map cross-species datasets to this joint macrogene space

Model Pretraining:

- Initialize with autoencoder using Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) loss

- Regularize reconstruction to preserve protein embedding similarities

- Use gene-to-macrogene weights to maintain functional relationships

Weakly Supervised Training:

- Employ metric learning with two-component objective:

- Separate different cells within same dataset using weak supervision

- Align similar cells across datasets in unsupervised manner

- Calibrate embedding distances to reflect cell label similarity

- Employ metric learning with two-component objective:

Cross-Species Differential Expression:

- Perform differential expression analysis on macrogenes instead of individual genes

- Aggregate gene contributions using gene-macrogene neural network weights

- Interpret biological meaning through highest-weight genes per macrogene

Spatial-Aware Foundation Models (Nicheformer)

Nicheformer represents a paradigm shift by incorporating both dissociated single-cell and spatially resolved transcriptomics data during pretraining, enabling the transfer of spatial context across species [3].

Experimental Protocol:

Data Curation:

- Compile SpatialCorpus-110M with 57 million dissociated and 53 million spatial cells

- Include data from 73 human and mouse tissues across multiple technologies

- Define orthologous genes across species for shared vocabulary

Tokenization Strategy:

- Convert expression vectors to ranked gene token sequences

- Compute technology-specific nonzero mean vectors to address platform biases

- Add contextual tokens for species, modality, and technology

Model Architecture & Training:

- Implement transformer with 12 encoder layers, 16 attention heads

- Use 1,500-token context length and 512-dimensional embedding space

- Train on combined dissociated and spatial data to capture spatial variation

Spatial Downstream Tasks:

- Spatial composition prediction: Model local cellular neighborhoods

- Spatial label prediction: Transfer spatial annotations across species

- Niche identification: Discover conserved tissue microenvironments

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Cross-Species Annotation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | CZ CELLxGENE [4], Human Cell Atlas [4], Tabula Sapiens [7] [2], Tabula Muris [2] | Provide standardized, annotated single-cell datasets for multiple species | Data quality varies; requires careful selection and filtering for pretraining |

| Protein Language Models | ESM-2 [2] | Generate protein embeddings that capture functional similarity beyond sequence homology | Enable remote homology detection; computationally intensive |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Technologies | MERFISH, Xenium, CosMx, ISS [3] | Provide spatial context for model training; enable spatial annotation transfer | Targeted gene panels limit gene coverage; technology-specific biases exist |

| Homology Databases | Orthologous gene mappings [1] [3] | Define evolutionary relationships between genes across species | Non-one-to-one homologies are crucial for distant species comparisons |

| Benchmarking Datasets | Asian Immune Diversity Atlas (AIDA) v2 [8] [5] | Provide independent validation across diverse populations and cell types | Essential for evaluating model generalization and avoiding data leakage |

| Computational Infrastructure | GPU clusters, High-performance computing [8] [5] | Enable model pretraining on millions of cells | Significant resources required; barrier to entry for some research groups |

Implementation Considerations

Practical Deployment Guidelines

Successful implementation of cross-species annotation models requires careful consideration of several practical factors. Model selection should be guided by specific research questions, as no single foundation model consistently outperforms others across all tasks [5]. For well-established cell types in closely related species, traditional methods may offer computational efficiency, while for novel cell types or distant species comparisons, foundation models with protein language model integration or spatial awareness provide distinct advantages.

Data quality and preprocessing significantly impact model performance. Careful batch effect correction, quality control filtering, and normalization are essential, particularly when integrating datasets across different technologies and species [4]. For cross-species applications, the handling of homologous relationships is critical—methods that incorporate non-one-to-one homologies or protein embeddings generally outperform those restricted to one-to-one gene matches, especially for evolutionarily distant species [1] [2].

Validation and Interpretation Frameworks

Rigorous validation is essential for cross-species annotations. Biological validation should include examination of conserved marker gene expression, assessment of functional enrichment in predicted cell types, and comparison with orthogonal data modalities when available [2]. Computational validation metrics should extend beyond simple accuracy to include ontological similarity measures that capture hierarchical relationships between cell types [5].

Interpretation of model outputs requires special consideration in cross-species contexts. Low-confidence predictions may indicate species-specific cell states rather than annotation failures. Attention mechanisms and feature importance analyses can reveal the gene programs driving cross-species alignments, providing biological insights beyond simple cell type transfer [1] [2].

Future Directions

The field of cross-species cell annotation foundation models is rapidly evolving, with several promising research directions emerging. Multimodal integration that combines transcriptomic, epigenetic, proteomic, and spatial information will likely enhance annotation accuracy and biological relevance [4]. Few-shot and zero-shot learning approaches are being developed to handle rare cell types and poorly characterized species [5]. Additionally, methods that explicitly model evolutionary distances and phylogenetic relationships may improve annotation transfer across broader taxonomic ranges.

As these models mature, development of more sophisticated benchmarking frameworks and standardized evaluation metrics will be crucial for advancing the field. Community efforts to create comprehensive cross-species benchmark datasets and establish best practices for model reporting will enable more systematic comparisons and accelerate progress in this transformative area of computational biology.

Quantitative Foundations of Evolutionary Divergence and Technical Variation

The development of robust cross-species foundation models requires a clear quantitative understanding of the biological and technical variabilities involved. The table below summarizes key metrics and benchmarks essential for designing and evaluating such models.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Benchmarks in Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis

| Metric / Component | Description / Value | Biological Significance / Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Distance (Data) | Training on 12 species spanning 1.5 billion years of evolution [9] | Enables model generalization across vast evolutionary scales and OOD prediction. |

| Data Scale (Model Training) | Models pretrained on >100 million cells from diverse public archives [10] | Provides the foundational "knowledge base" for the model's understanding of cellular biology. |

| CCD Boundary Conservation (Human vs. Chimpanzee) | 71.2% of human CCD boundaries are shared with chimpanzees [11] | Provides a quantitative measure of 3D genome architecture conservation between close species. |

| Minimum Contrast Ratio (WCAG AA - Large Text) | At least 3:1 [12] [13] | Ensures accessibility and legibility for data visualization interfaces and published findings. |

| Enhanced Contrast Ratio (WCAG AAA - Body Text) | At least 7:1 [14] | A higher standard for legibility in critical displays and publications. |

Experimental Protocols for scFM Development and Benchmarking

Protocol: Assembling a Cross-Species Pretraining Corpus

Objective: To compile a large-scale, diverse, and high-quality single-cell dataset for pretraining a foundational model capable of cross-species generalization.

Materials:

- Public Data Archives: CZ CELLxGENE [10], Tabula Sapiens [9], NCBI GEO/SRA [10], EMBL-EBI Expression Atlas [10], PanglaoDB [10].

- Computing Infrastructure: High-performance computing cluster with substantial memory and storage.

Methodology:

- Data Aggregation: Download single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from multiple public archives and consortia (e.g., Human Cell Atlas).

- Curation & Filtering:

- Retain datasets with clear metadata on species, tissue, and cell source.

- Filter out low-quality cells based on standard QC metrics (e.g., gene counts, mitochondrial read percentage).

- Remove rarely expressed genes to reduce noise.

- Data Integration: Apply batch correction techniques (e.g., mutual nearest neighbors) to mitigate technical variations between different studies and platforms, while preserving robust biological signals [10].

- Non-Redundancy Assurance: Implement strategies to ensure a balanced representation of species, tissues, and cell states, preventing the model from being biased towards over-represented conditions [10].

Protocol: Model Pretraining with Tokenization and Transformer Architecture

Objective: To train a transformer-based model on the curated corpus using self-supervised learning, enabling it to learn fundamental principles of gene expression.

Materials:

- Processed Data Corpus: The output of Protocol 2.1.

- Software Frameworks: PyTorch or TensorFlow.

- Hardware: Multiple GPUs with high VRAM (e.g., NVIDIA A100/H100).

Methodology:

- Tokenization:

- Gene Selection: For each cell, select the top

khighly variable genes or all genes above an expression threshold. - Input Representation: Create a token for each gene that combines its unique identifier and normalized expression value. One common strategy is to rank genes by expression level to create a deterministic sequence [10].

- Special Tokens: Prepend a

[CELL]token to aggregate cell-level context and append modality tokens ([RNA],[ATAC]) for multi-omics models [10].

- Gene Selection: For each cell, select the top

- Model Architecture (Transformer):

- Configure a transformer encoder (e.g., BERT-like) or decoder (e.g., GPT-like) architecture. Encoder models with bidirectional attention are often used for classification and embedding tasks [10].

- Set model parameters: embedding dimensions, number of attention heads, number of layers, and feed-forward network dimensions, scaling according to available computational resources.

- Self-Supervised Pretraining:

- Masked Language Modeling (MLM): Randomly mask a portion (e.g., 15%) of the gene tokens in the input sequence. Train the model to predict the expression value or identity of the masked genes based on the context provided by the unmasked genes [10].

- Training Loop: Iterate over the entire corpus for multiple epochs, optimizing the model parameters to minimize the prediction loss.

Protocol: Cross-Species Cell Annotation and Benchmarking

Objective: To evaluate the model's ability to accurately transfer cell type labels from a well-annotated reference species to a target species, including out-of-distribution (OOD) species.

Materials:

- Pretrained scFM: The output of Protocol 2.2.

- Benchmark Datasets: Annotated single-cell data from target species (e.g., rhesus macaque, marmoset) not seen during pretraining [9].

Methodology:

- Embedding Generation: Pass the single-cell data from the target species through the pretrained model to obtain a contextual cell embedding for each cell.

- Label Transfer: Use a simple classifier (e.g., k-nearest neighbors) on the embedding space to predict cell type labels for the target species cells, using the labeled reference species data (e.g., human) as the source.

- Performance Benchmarking:

- Compare the model's predictions against held-out, manually annotated ground-truth labels for the target species.

- Calculate standard metrics: accuracy, F1-score, and adjusted Rand index (ARI).

- Benchmark against baseline models without pretraining or with alternative architectures to demonstrate the scFM's superior performance in OOD species classification [9].

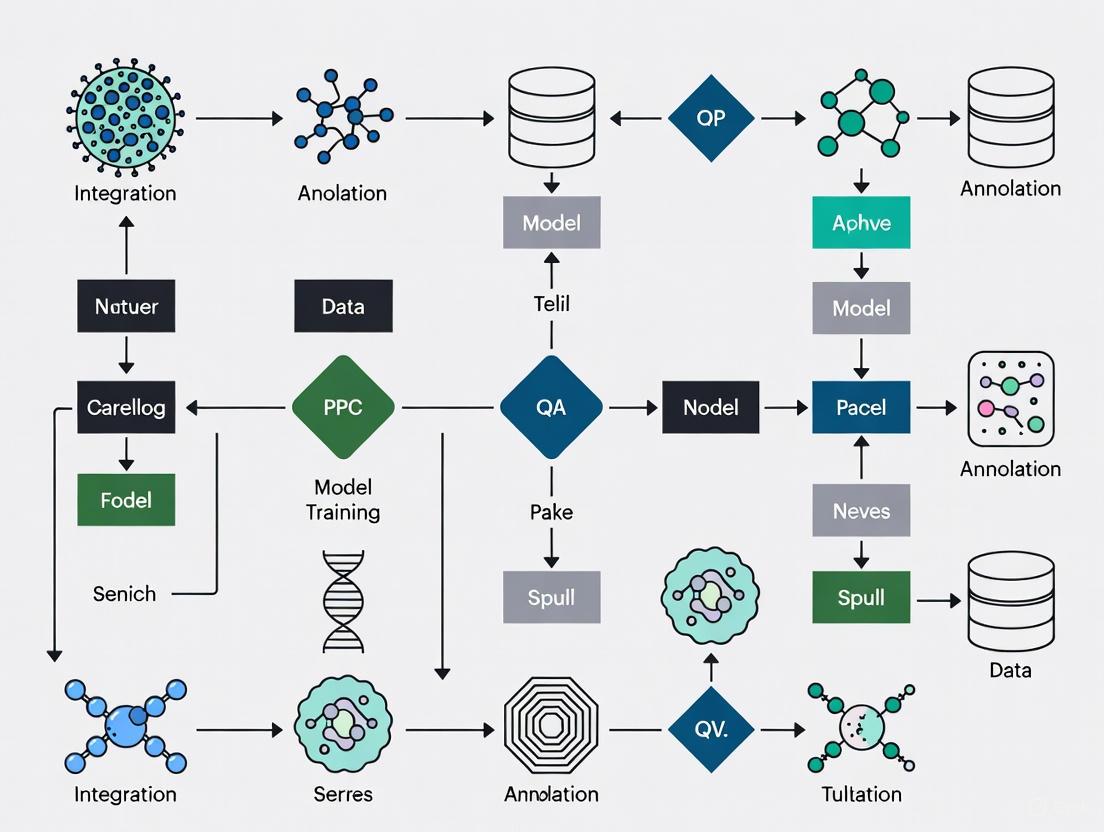

Visualization of Computational Workflows

scFM Pretraining and Application

Cross-Species Label Transfer Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Cross-Species Foundation Model Research

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated Data Platforms | Data Repository | Provides unified access to standardized, annotated single-cell datasets for model training. | CZ CELLxGENE [10], Tabula Sapiens [9] |

| Multi-Omics Data | Data Type | Enables training of models that can integrate gene expression with chromatin accessibility for a more comprehensive view. | scATAC-seq, Multiome Sequencing [10] |

| Pretrained Foundation Models | Software Model | Provides a starting point for transfer learning, saving computational resources and time. | TranscriptFormer [9], scGPT [10], scBERT [10] |

| Accessibility Evaluation Tools | Software Tool | Ensures that data visualization dashboards and UIs meet contrast standards for inclusive science. | axe DevTools [15], WebAIM Color Checker [12] |

Application Notes

Cross-species cell annotation foundation models represent a paradigm shift in biomedical research, enabling the transfer of biological knowledge across evolutionary distances. By leveraging large-scale single-cell transcriptomic data from multiple species, these models decipher conserved and species-specific cellular principles, accelerating discoveries from basic evolution to translational medicine [10] [9]. The following applications highlight their transformative potential.

Deciphering Cellular Phylogenies and Evolutionary Conservation

Objective: To identify evolutionarily conserved gene expression programs and cell-type relationships across species, providing insights into fundamental cellular mechanisms preserved over billions of years of evolution.

Background: A primary challenge in evolutionary biology is distinguishing conserved core biological processes from species-specific adaptations. Single-cell foundation models (scFMs), trained on diverse multi-species datasets, learn latent representations that encapsulate both universal cellular states and lineage-specific differences [9]. For instance, TranscriptFormer was pretrained on 112 million cells from 12 species, covering 1.5 billion years of evolutionary divergence, creating a model that intrinsically understands cellular homology and variation [9].

Key Findings:

- Conserved Cell Types: Models can identify orthologous cell types across vast evolutionary distances (e.g., from fish to primates) based on conserved gene expression signatures, aiding in the annotation of cell types in non-model organisms [9].

- Evolutionary Shifts in Gene Programs: Analysis of a cross-species retinal atlas revealed that while broad retinal cell types are conserved, photoreceptor cells, particularly rods, show significant evolutionary shifts. Opsin expression and associated transcriptional programs in cones and rods display species-specific patterns adapted to different ecological niches [16].

Quantitative Performance: The following table summarizes the cross-species cell type classification performance of a foundational model (TranscriptFormer) compared to baseline methods.

Table 1: Cross-Species Cell Type Classification Accuracy (%)

| Model / Species | Rhesus Macaque | Marmoset | Mouse | Zebrafish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TranscriptFormer | 92.5 | 89.7 | 85.1 | 78.3 |

| Baseline Model A | 88.1 | 84.3 | 79.5 | 70.2 |

| Baseline Model B | 90.2 | 86.5 | 81.8 | 72.9 |

Note: Accuracy reflects the model's ability to correctly annotate cell types in species not seen during training (out-of-distribution species). Results are aggregated from benchmark tasks detailed in the TranscriptFormer preprint [9].

Translating Disease Mechanisms and Identifying Therapeutic Targets

Objective: To leverage cross-species models to understand human disease pathophysiology, predict disease states from cellular transcriptomes, and improve the translational relevance of animal models.

Background: A significant obstacle in drug development is the failure of findings from animal models to translate to human patients. scFMs can identify conserved disease-associated gene networks and predict cellular responses to perturbation, thereby providing a more reliable bridge between model organisms and human biology [10] [9].

Key Findings:

- Disease State Prediction: TranscriptFormer demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in identifying SARS-CoV-2-infected cells from non-infected cells in lung tissue without requiring fine-tuning on labeled infection data. This indicates its ability to capture fundamental, conserved transcriptional shifts associated with disease states [9].

- Modeling Human Disorders: The cross-species retinal atlas facilitates the selection of appropriate animal models for studying human color vision disorders by clarifying the concordance and discordance in cone subtype transcription factors and metabolic pathways between species [16].

- Insight into Ageing: Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of the ageing human brain revealed a common downregulation of housekeeping genes involved in ribosomes, transport, and metabolism across most cell types, while neuron-specific genes remained stable. This provides a conserved transcriptomic signature of brain ageing [17].

Quantitative Performance: The table below compares the performance of foundational models in predicting disease states against baseline models.

Table 2: Disease State Prediction Performance (F1 Score)

| Model / Disease Task | SARS-CoV-2 Infection | Ageing Brain Classification | Cancer Cell Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| TranscriptFormer | 0.94 | N/A | N/A |

| scBERT | N/A | 0.89 | N/A |

| scGPT | N/A | N/A | 0.91 |

| Baseline Model A | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| Baseline Model B | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

Note: F1 score (0-1) is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. Higher scores indicate better performance. scBERT and scGPT are other prominent single-cell foundation models [10]. Ageing brain classification performance is derived from benchmarking on human prefrontal cortex snRNA-seq data [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Cross-Species Cell Type Annotation Using TranscriptFormer

Purpose: To annotate cell types in a target species (e.g., Marmoset) using a model trained on a source species (e.g., Human).

Principle: Foundation models like TranscriptFormer learn a shared latent space where analogous cell types from different species are positioned proximately based on conserved gene expression patterns, enabling knowledge transfer without explicit labels in the target species [9].

Materials:

- Query Dataset: Single-cell RNA-seq count matrix from the target species.

- Reference Model: Pretrained TranscriptFormer model.

- Computing Environment: High-performance computing node with GPU (e.g., NVIDIA A100, 40GB VRAM recommended).

- Software: Python (v3.9+), PyTorch (v1.12+), TranscriptFormer codebase.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: a. Gene Orthology Mapping: Map genes from the target species to their one-to-one orthologs in the human genome using a resource like Ensembl BioMart [18]. b. Count Normalization: Normalize raw counts for library size using a method like counts per million (CPM). Replace zero values with 1 and apply a log2 transformation [18]. c. Filtering: Filter out cells with an abnormally high mitochondrial gene percentage and genes expressed in fewer than a minimum number of cells (e.g., < 10).

- Model Inference: a. Embedding Generation: Feed the preprocessed query dataset into the TranscriptFormer model to generate a latent embedding for each cell. This embedding is a numerical vector representing the cell's state in the model's shared cross-species space [9].

- Cell Type Prediction: a. Nearest Neighbor Search: For each cell in the target species, find the k-nearest neighbors (e.g., k=5) in the reference embedding space (e.g., human cell atlas) based on cosine similarity. b. Label Transfer: Assign the most frequent cell type label from the k-nearest reference cells to the query cell.

- Validation: a. Differential Expression: Perform differential expression analysis between the newly annotated clusters to confirm they express expected marker genes for the assigned cell type [18]. b. Visualization: Use UMAP or t-SNE to visualize the joint embedding of reference and query cells, assessing whether cell types cluster by biological function rather than by species [9].

Protocol: Cross-Study and Cross-Species Normalization with CSN

Purpose: To harmonize two or more single-cell datasets from different studies and species, removing technical batch effects while preserving meaningful biological differences.

Principle: The Cross-Species Normalization (CSN) method is designed to explicitly reduce technical variance between datasets while conserving interspecies biological variation. It is based on an evaluation criterion that maximizes the removal of experimental artifacts and minimizes the loss of biological signal [18].

Materials:

- Datasets: Log2-transformed expression matrices from multiple studies/species (e.g., human dataset H and mouse dataset M).

- Orthologous Genes: A list of one-to-one orthologous genes between the species.

- Software: R or Python implementation of the CSN algorithm.

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: a. Merge the datasets into a combined expression matrix, including only the one-to-one orthologous genes. b. Generate a batch vector indicating the study/species of origin for each sample.

- Normalization: a. Apply the CSN algorithm to the combined matrix. The algorithm learns a transformation that aligns the distributions of the datasets in a lower-dimensional space. b. The output is a normalized expression matrix where technical differences between studies are minimized.

- Performance Evaluation: a. Technical Effect Reduction: Select two biologically similar conditions, C1 and C2, profiled in both experiments (H and M). After normalization, the within-condition variance (e.g., HC1 vs. MC1) should be significantly reduced. b. Biological Effect Preservation: Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) between conditions C1 and C2 in the normalized data. The method should preserve a high number of true biological DEGs. Compare the number of conserved DEGs before and after normalization using statistical tests (e.g., two-sample t-test, FDR correction) [18].

Visualization Diagrams

scFM Training and Application

Cross-Species Normalization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Cross-Species Analysis

| Item | Function & Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| CZ CELLxGENE | A curated data platform providing unified access to millions of annotated single-cells from diverse species and tissues. Used for model pre-training and validation [9]. | https://cellxgene.cziscience.com/ |

| Ensembl BioMart | A data mining tool to obtain lists of one-to-one orthologous genes between species (e.g., human and mouse). Critical for gene space alignment before cross-species analysis [18]. | http://www.ensembl.org/biomart/martview |

| TranscriptFormer Model | A generative, cross-species foundation model for single-cell transcriptomics. Used for out-of-distribution cell type annotation, disease prediction, and gene interaction modeling [9]. | Available via CZI's virtual cell platform. |

| Cross-Species Normalization (CSN) | A dedicated normalization algorithm for harmonizing datasets from different studies and species. Reduces technical effects while better preserving biological differences compared to EB, DWD, or XPN [18]. | R/Python implementation as described in [18]. |

| scPred Model | A classification model used to map and align cell types across species within a defined atlas, enabling the identification of conserved and variable cell types [16]. | R package 'scPred'. |

{ "abstract": "The analysis of biological systems has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from isolated single-species models to integrative multi-species frameworks. This evolution, driven by the recognition of complex ecological interactions and the advent of high-throughput single-cell genomics, is revolutionizing fields from conservation ecology to therapeutic development. This Application Note details the quantitative evidence supporting this paradigm shift, provides standardized protocols for implementing multi-species analysis, and visualizes the core workflows and reagent tools essential for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in cross-species investigation." }

The traditional approach to modeling biological systems has long been dominated by single-species models. In ecology, these models focused on the population dynamics of a single species in isolation [19]. Similarly, in early single-cell genomics, cell type annotation was often performed by analyzing one dataset or one species at a time, relying on manual curation and limited marker genes [20] [21]. These methods, while useful for initial insights, fundamentally ignored the complex web of biological interactions and shared evolutionary patterns that define real-world biological systems. The intrinsic limitations of this single-species approach—including an inability to accurately forecast population changes in ecological communities and a lack of robustness when annotating cell types across diverse datasets or species—created a pressing need for more sophisticated frameworks [19] [22].

The shift to multi-species analysis frameworks represents a response to these limitations, enabled by advances in computational power and the accumulation of large-scale datasets. In ecology, this means jointly modeling interacting species to produce superior forecasts [22]. In single-cell biology, it has given rise to cross-species foundation models like TranscriptFormer, which are pretrained on millions of cells from multiple species to learn conserved biological principles [10] [9]. These models leverage the transformative transformer architecture to interpret the "language" of cells across evolutionary distances, allowing for the prediction of cell types and disease states even in species not seen during training [10] [9]. This document details the experimental evidence, protocols, and tools that underpin this critical transition, providing a roadmap for researchers to implement multi-species analyses.

Quantitative Evidence: Comparing Single vs. Multi-Species Frameworks

Empirical evidence consistently demonstrates the superior performance of multi-species frameworks over their single-species predecessors. The tables below summarize key quantitative comparisons from ecological and single-cell genomic studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Ecological Forecasting Models

| Model Type | Key Features | Forecast Performance | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Species Model | Models species in isolation; ignores biotic interactions [19]. | Lower accuracy in hindcast and forecast vs. multi-species models [22]. | Rodent population dynamics over 25 years [22]. |

| Multi-Species Dynamic Model | Jointly models species with shared environmental responses & temporal dependencies [22]. | Superior hindcast and forecast performance; captures nonlinear, lagged effects [22]. | Nine rodent species in a semi-arid community [22]. |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Single-Cell Annotation Tools

| Method / Model | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Annotation | Expert curation of marker genes for each cluster [21]. | Considered the "gold standard"; allows for deep biological insight [21]. | [21] |

| Automated Tools (e.g., PCLDA) | Simple statistical pipelines (PCA, LDA) for classification [23]. | High interpretability, computational efficiency, and stability across protocols [23]. | [23] |

| Foundation Models (e.g., TranscriptFormer, scGPT) | Transformer-based AI pretrained on massive, multi-species atlases [10] [9]. | Cross-species cell type prediction; identification of disease states; predicts gene-gene interactions [9]. | [10] [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Species Analysis

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Cell Annotation with a Foundation Model

This protocol details the use of a pre-trained foundation model, such as TranscriptFormer, to annotate cell types in a query dataset from a species that was not necessarily part of the model's training data [9].

Input Data Preparation (Query Dataset)

- Format your single-cell data (e.g., scRNA-seq raw counts) into an

anndataobject and save it as an H5AD file [24]. - Ensure the object contains raw counts in

adata.X,adata.raw.X, or a specified layer. Perform initial quality control to filter out low-quality cells [24]. - The model will use standardized gene identifiers. Ensure your gene identifiers match the expected format (e.g., HGNC symbols for human) [21].

- Format your single-cell data (e.g., scRNA-seq raw counts) into an

Model Selection and Setup

- Download a pre-trained model suitable for your tissue of interest (e.g., a pan-tissue immune model or a lung model) [24].

- The first execution with a specific model will trigger an automatic download and local caching for future use [24].

- Install the required software environment. For example, for CZ CELLxGENE Annotate, installation can be done via pip:

pip install 'cellxgene[annotate]'within a Python 3.9+ environment [24].

Execution of Annotation

- Run the annotation command, specifying your input file, the model URL, and the output file path.

- Example command:

cellxgene annotate ./query_data.h5ad --model-url https://model-repository.org/model.zip --output-h5ad-file ./annotated_data.h5ad[24]. - The tool will generate a new H5AD file containing predicted cell type labels, confidence scores, and a UMAP projection of the query data into the reference embedding space [24].

Exploration and Validation

- Open the annotated H5AD file in an exploration tool like CELLxGENE:

cellxgene launch ./annotated_data.h5ad[24]. - Visually inspect the results by coloring cells by the predicted cell type (

cxg_cell_type_predicted) and the associated uncertainty score (cxg_cell_type_predicted_uncertainty) [24]. - Validate predictions by examining the expression of known marker genes for the assigned cell types. Use differential expression analysis between clusters to identify defining genes and refine annotations if necessary [24].

- Open the annotated H5AD file in an exploration tool like CELLxGENE:

Protocol 2: Building a Multi-Species Ecological Forecasting Model

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a dynamic generalized additive model (GAM) to forecast the population abundances of multiple interacting species, as validated in rodent communities [22].

Data Compilation and Preprocessing

- Gather time-series data on species abundances (e.g., monthly capture counts for all species of interest over multiple years) [22].

- Compile concurrent time-series data for relevant environmental drivers, such as temperature and vegetation greenness (e.g., NDVI) [22].

- Address data complexities like missing values, observation errors, and temporal autocorrelation within the abundance data [22].

Model Specification

- Define a state-space model structure where the observed counts are a function of a latent (true) abundance state.

- For the latent state process, specify a multivariate model that includes:

- Nonlinear environmental effects: Model the effect of drivers (e.g., temperature) using smooth functions (splines) within the GAM framework, potentially over multiple temporal lags [22].

- Multi-species dependencies: Incorporate lagged abundances of other species as predictors to account for biotic interactions like competition or predation [22].

- Unobserved temporal autocorrelation: Include latent autoregressive terms to capture intrinsic population dynamics not explained by the covariates [22].

Model Fitting and Inference

- Fit the model using a statistical framework capable of handling the complexity of state-space GAMs, such as those implemented in Stan [22].

- Perform model comparison against simplified single-species models (which omit multi-species dependencies) using hindcast predictive accuracy [22].

- Analyze the model outputs to identify key drivers, the strength and nature of species interactions, and the form of environmental responses (e.g., nonlinearities, critical lags) [22].

Forecast Generation and Evaluation

- Generate near-term (e.g., up to 12 months) forecasts of species abundances from the fitted multi-species model.

- Rigorously evaluate forecast performance against held-out future data and compare the accuracy to forecasts generated from the single-species benchmarks [22].

Visualizing Workflows and Logical Frameworks

The Evolution of Single-Cell Annotation

Multi-Species Ecological Forecasting Model

Successful implementation of multi-species frameworks relies on a suite of computational tools and curated data resources.

Table 3: Key Resources for Multi-Species Single-Cell Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Relevant Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CZ CELLxGENE | Data Platform / Tool | Provides unified access to millions of annotated single-cells; hosts automated annotation pipeline [24]. | [24] [9] |

| ACT (Annotation of Cell Types) | Web Server | Provides a knowledge-based platform for cell type enrichment using a hierarchically organized marker map [21]. | [21] |

| TranscriptFormer | Foundation Model | A generative, multi-species model for predicting cell types, disease states, and gene interactions across evolution [9]. | [9] |

| scGPT / scBERT | Foundation Model | Transformer-based models for single-cell biology, pretrained on large corpora for various downstream tasks [10]. | [10] |

| PCLDA | Annotation Algorithm | A simple, interpretable, and robust pipeline for cell annotation based on PCA and LDA [23]. | [23] |

| Hierarchical Marker Map | Curated Knowledgebase | A collection of canonical markers and differentially expressed genes organized by tissue and cell type, used for enrichment testing [21]. | [21] |

The transition from single-species to multi-species analysis frameworks is a cornerstone of modern biology, enabling more accurate predictions and a deeper, more unified understanding of complex systems. In ecology, multi-species models are proving essential for reliable forecasting and informed conservation [22]. In single-cell genomics, foundation models like TranscriptFormer are breaking down species barriers, creating a powerful new paradigm for discovering conserved cellular functions and disease mechanisms [9]. The protocols, tools, and visualizations provided in this Application Note offer a practical foundation for researchers to integrate these advanced multi-species approaches into their work, ultimately accelerating progress in both fundamental biology and therapeutic development.

Architectural Blueprints: How Leading Foundation Models Decipher Cellular Language Across Species

The transformer architecture, originally designed for natural language processing (NLP), has catalyzed a revolution in computational biology. Its core mechanism, self-attention, allows models to dynamically weigh the importance of different elements in a sequence, whether words in a sentence or genes in a cell [25]. This capability to capture complex, long-range dependencies makes it uniquely suited for biological data. In single-cell transcriptomics, this has led to the emergence of single-cell Foundation Models (scFMs)—large-scale deep learning models pretrained on vast datasets that can be adapted for diverse downstream tasks like cell type annotation and gene regulatory network inference [10] [4]. These models treat a cell's transcriptome as a "sentence" and individual genes as "words," thereby learning the fundamental language of cellular biology from millions of cells across diverse tissues and species [10].

Application Notes: Key Use Cases and Performance

Transformer-based models are delivering state-of-the-art performance across a wide spectrum of biological applications. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of several prominent models on key tasks.

Table 1: Performance of Transformer-Based Models in Biological Applications

| Model Name | Primary Application | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| scGREAT [26] | Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) Inference | Average AUROC (Cell-type-specific ChIP-seq) | 90.5% (range 81.4% - 95.0%) |

| scGREAT (vs. other methods) [26] | GRN Inference | Performance improvement in AUROC vs. GENELink, GNE, CNNC | +6.3%, +15.5%, +23.9% respectively |

| Delphi-2M [27] | Disease Trajectory Prediction | Average AUC (across disease spectrum) | ~0.76 |

| scTab [28] | Cross-tissue Cell Type Annotation | Scaling performance | Performance scales with model size & training data size |

| TranscriptFormer [9] | Cross-species Cell Type Annotation | Cell type classification in unseen species | State-of-the-art (outperforms comparable models) |

Cross-Species Cell Annotation

A premier application of scFMs is cross-species cell annotation. TranscriptFormer, a generative multi-species model trained on 112 million cells from 12 species, demonstrates a remarkable ability to identify cell types in species not included in its training data (e.g., rhesus macaque and marmoset) [9]. This capability to translate gene expression patterns across vast evolutionary distances is crucial for biomedical research, as it helps predict whether findings in model organisms are likely to translate to humans.

Gene Regulatory Network Inference

Inferring the complex regulatory interactions between transcription factors and their target genes is a fundamental challenge in biology. scGREAT leverages a transformer backbone to infer GRNs from single-cell transcriptomics data. Its superior performance, outperforming other contemporary methods on seven benchmark datasets, highlights the transformer's ability to capture the intricate, non-linear relationships within gene regulatory systems [26].

Predicting Disease Trajectories

Beyond single-cell analysis, transformers are being adapted to model human health. Delphi-2M uses a modified GPT architecture to learn patterns of disease progression from population-scale health records [27]. It can predict future rates of over 1,000 diseases conditional on an individual's past medical history, providing meaningful estimates of potential disease burden for up to 20 years and enabling a new paradigm in personalized health risk assessment.

Protocols for Model Implementation and Experimentation

Protocol: Building a Single-Cell Foundation Model

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a transformer-based model for single-cell transcriptomics, synthesizing methodologies from models like scGPT, scBERT, and TranscriptFormer [10] [4].

1. Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Data Aggregation: Collect a large and diverse corpus of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from public repositories like CELLxGENE, which hosts over 100 million unique cells [10] [4].

- Quality Control: Filter cells and genes to remove low-quality data. Perform standard normalization to account for varying sequencing depth.

- Batch Effect Consideration: Decide on a strategy for handling technical batch effects. Some models incorporate batch information as special tokens, while others report robustness without them [10].

2. Tokenization and Input Representation

- Gene Token Definition: Define each gene as a distinct token. The input for a single cell is its expression profile across these gene tokens.

- Sequential Ordering: Impose an order on the non-sequential gene expression data. Common strategies include:

- Embedding: Create an embedding vector for each gene token that combines a learned representation of the gene's identity with its expression value in the current cell. Add positional encodings to inform the model of the gene's rank or position in the sequence [25] [10].

3. Model Architecture and Pretraining

- Architecture Selection: Choose a transformer variant. Bidirectional encoder architectures (e.g., BERT-style) are common for classification tasks, while decoder architectures (e.g., GPT-style) are used for generation [10].

- Self-Supervised Pretraining: Train the model on a pretext task that does not require labeled data. A standard task is masked language modeling, where a random subset of gene tokens is masked, and the model is trained to predict them based on the context of the remaining genes [10] [4].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Follow empirical scaling laws, optimizing parameters like embedding dimensionality and the number of layers/heads based on available data [27].

4. Downstream Task Fine-Tuning

- Adapt the pretrained model to specific tasks (e.g., cell type annotation, disease state prediction) using smaller, task-specific labeled datasets. This transfer learning step leverages the general biological knowledge the model acquired during pretraining.

Diagram: Single-Cell Foundation Model Workflow

Protocol: Cross-Species Cell Annotation with TranscriptFormer

This protocol details the application of a pretrained model like TranscriptFormer for annotating cell types in a new, unlabeled dataset from a novel species [9].

1. Model Acquisition and Input Preparation

- Obtain the pretrained TranscriptFormer model.

- Preprocess your target scRNA-seq dataset (from the novel species) to match the model's expected input format, including gene filtering and normalization.

2. Generation of Cell Embeddings

- Feed the preprocessed gene expression matrix from the target dataset through the TranscriptFormer model.

- Extract the contextualized cell embeddings from the model's output. These are dense vector representations that encode the cell's state based on its gene expression profile, as understood in the context of the model's multi-species training.

3. Cell Type Prediction

- Similarity-Based Annotation: Compare the embeddings of the unlabeled target cells to the embeddings of a reference set of well-annotated cells from a related species. Assign the cell type label of the most similar reference cell(s).

- Classifier-Based Annotation: Train a simple classifier (e.g., a linear model) on the reference cell embeddings and their known labels. Use this classifier to predict labels for the target cell embeddings.

4. Validation and Interpretation

- Validate the predictions using known marker genes or other orthogonal biological knowledge.

- Use the model's attention mechanisms to gain insight into which genes were most influential in the classification decision.

Diagram: Cross-Species Annotation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and application of biological transformer models rely on a suite of computational "reagents" and resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for scFM Development

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | CZ CELLxGENE [9], Human Cell Atlas [10], GEO/SRA [10], PanglaoDB [10] | Provide large-scale, curated single-cell datasets essential for pretraining foundational models. |

| Model Architectures | Transformer Encoder (BERT-style) [10], Transformer Decoder (GPT-style) [27] [10], Hybrid Architectures | Serve as the core computational engine for building attention-based models. |

| Pretraining Tasks | Masked Language Modeling [10] [4] | Enables self-supervised learning on unlabeled data, forcing the model to learn meaningful biological context. |

| Benchmarking Platforms | BEELINE [26] | Provides standardized datasets and evaluation frameworks to fairly compare model performance. |

| Ontologies | Cell Ontology (CL) [28] | Provides a structured, hierarchical vocabulary for cell types, critical for standardizing model outputs and evaluations. |

Transformer architectures have successfully bridged the gap between natural language and the language of biology, enabling the creation of powerful foundation models for single-cell transcriptomics. These models, trained on millions of cells across diverse species and conditions, are revolutionizing biological discovery. They excel at cross-species cell annotation, gene regulatory network inference, and disease trajectory prediction, providing scalable and accurate tools for researchers and drug developers. As data corpora continue to expand and model architectures are refined, these AI-powered virtual cells promise to deepen our understanding of cellular function and accelerate the development of new therapeutics.

The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to study cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. However, a significant challenge remains in comparing and annotating cell types across different species, which is crucial for understanding evolutionary biology and translating findings from model organisms to humans. Cross-species cell annotation foundation models address this challenge by leveraging large-scale single-cell transcriptomic data from multiple organisms to learn universal representations of cellular states [10]. These models typically employ transformer-based architectures, originally developed for natural language processing, to decipher the "language" of gene regulation by treating individual cells as sentences and genes or genomic features as words [10] [5].

The fundamental paradigm involves pre-training on massive, diverse single-cell datasets through self-supervised learning objectives, enabling the models to capture core biological principles of gene regulation and cell identity that are conserved across evolutionary distances [29] [9]. This pre-training phase allows the models to develop a foundational understanding of cellular biology that can then be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks such as cell type classification, disease state identification, and gene regulatory network inference [10] [5]. By integrating data from multiple species, these models can decipher universal gene regulatory mechanisms and facilitate knowledge transfer between organisms, accelerating the discovery of critical cell fate regulators and candidate drug targets [29] [30].

Model Specifications and Architectural Comparison

Table 1: Key specifications of cross-species cell annotation foundation models

| Model | Training Data Scale | Species Coverage | Architecture | Parameters | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GeneCompass | 101.7M cells after processing [29] | Human, Mouse [29] | 12-layer transformer [29] | Not specified | Integrates 4 types of prior biological knowledge [29] |

| TranscriptFormer | 112M cells [9] | 12 species across 1.5B years of evolution [9] | Transformer encoder, 12 layers, 16 attention heads [31] | 368-542 million [31] | Expression-aware attention; ESM-2 protein embeddings [31] |

| Icebear | Not specified | Mouse, Opossum, Chicken [6] | Neural network framework [6] | Not specified | Decomposes single-cell measurements into cell identity, species, and batch factors [6] |

| CAME | Not explicitly detailed in search results | Information not available in search results | Information not available in search results | Information not available in search results | Information not available in search results |

The architectural implementations of these models reflect their specialized approaches to cross-species analysis. GeneCompass employs a knowledge-informed framework that incorporates four types of prior biological knowledge during pre-training: gene regulatory networks, promoter sequences, gene family annotations, and gene co-expression relationships [29]. It uses a masked language modeling strategy where 15% of gene inputs are randomly masked in each cell, with the model trained to recover both gene IDs and expression values simultaneously [29]. This approach enhances the model's ability to capture intricate gene relationships in a context-aware manner.

TranscriptFormer introduces a novel expression-aware attention mechanism where expression counts are incorporated as a log-count bias term in the attention matrix, avoiding explicit token duplication [31]. It utilizes ESM-2 protein embeddings for gene representation and includes an assay token to capture sequencing platform metadata [31]. The model is trained autoregressively for both gene identities and their counts, and employs strategic shuffling to randomly permute expressed genes each batch to remove positional bias [31].

Icebear employs a fundamentally different approach by designing a neural network framework that decomposes single-cell measurements into separable factors representing cell identity, species, and batch effects [6]. This factorization enables the model to perform cross-species prediction of gene expression profiles by swapping the species factor corresponding to each cell, facilitating direct comparison of expression profiles across species at single-cell resolution without relying on external cell type annotations [6].

Figure 1: Architectural overview of cross-species foundation models showing shared inputs and diverse application outputs

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarking

Model Training and Evaluation Protocols

The training methodologies for these foundation models involve sophisticated pre-training strategies on massive single-cell datasets. GeneCompass was trained on over 120 million human and mouse single-cell transcriptomes (with 101.7 million cells retained after quality control) using a self-supervised learning approach [29] [30]. The model incorporates homologous gene mapping between species, with 17,465 homologous genes out of 36,092 total genes in its token dictionary [29]. For each cell, the top 2048 genes are selected to construct the context after normalizing and ranking gene expression values, then absolute gene expression values are concatenated with corresponding gene IDs for stronger supervision constraints [29].

TranscriptFormer employs a multi-species training approach with balanced sampling across evolutionary diverse organisms. The model up-weights low-resource species to balance against human and mouse data dominance [31]. It was trained using the AdamW optimizer with linear warm-up followed by cosine decay, with a global batch size of approximately 4-5 million tokens [31]. The training processed approximately 3.5 trillion tokens over up to 15 epochs using mixed-precision floating point (fp16/bf16) on H100 GPU clusters with Distributed Data Parallel (DDP) [31].

Icebear's training protocol involves a unique decompositional approach where the model learns to separate species factors from cell identity factors [6]. This enables the model to perform cross-species imputation by swapping species factors while preserving cell identity factors. The framework demonstrates particular utility for predicting single-cell profiles in missing cell types across species and facilitates direct comparison of expression profiles for conserved genes that have undergone chromosomal repositioning during evolution [6].

Table 2: Performance benchmarking across key biological tasks

| Model | Cross-Species Cell Type Classification (Macro F1) | Disease State Identification | Gene Regulatory Inference | Evolutionary Distance Generalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GeneCompass | Superior to SOTA for single species [29] | Demonstrated for cell fate transition [29] | Validated via in silico gene deletion [29] | Captures homology across human and mouse [29] |

| TranscriptFormer | F1 > 0.7 for species separated by ~600+ million years [31] | F1 ~0.85-0.86 for COVID-19 infected vs. healthy [31] | Predicts cell type-specific TF interactions [9] | Covers 1.5B years of evolution across 12 species [9] |

| Icebear | Enables single-cell resolution comparison [6] | Predicts human Alzheimer's disease from mouse models [6] | Reveals evolutionary expression patterns [6] | Applied to eutherians, metatherians, and birds [6] |

Benchmarking Results and Comparative Performance

Comprehensive benchmarking reveals the distinct strengths and specializations of each model. A recent systematic evaluation of six single-cell foundation models against established baselines using 12 metrics across diverse biological tasks provides insights into their relative performance characteristics [5]. The study found that no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, emphasizing the need for tailored model selection based on factors such as dataset size, task complexity, and computational resources [5].

TranscriptFormer demonstrates remarkable cross-species generalization capabilities, maintaining F1 scores above 0.7 for species separated by approximately 600+ million years of evolution, such as stony coral [31]. For human-specific tasks, it achieves macro F1 scores up to 0.91+ on the Tabula Sapiens v2 dataset and approximately 0.85-0.86 in distinguishing SARS-CoV-2 infected versus non-infected cells in human lung tissue [31].

GeneCompass has been experimentally validated for its ability to capture biological meaningfulness through in silico gene deletion studies [29]. When the model performed in silico deletion of GATA4 or TBX5 (genes with known roles in congenital heart disease) in human fetal cardiomyocytes, it correctly identified greater impact on their direct target genes compared to indirect targets, housekeeping genes, and other congenital heart disease-related genes, with statistically significant differences (p-value < 0.05 by t-test) [29]. This demonstrates that the pre-trained model effectively learned genuine gene regulatory relationships.

Icebear has been applied to study evolutionary biology questions, particularly regarding X-chromosome upregulation (XCU) in mammals [6]. By predicting and comparing gene expression changes across eutherian mammals (mouse), metatherian mammals (opossum), and birds (chicken), Icebear revealed gene expression pattern shifts that support the existence of mammalian XCU and suggest the extent and molecular mechanisms of XCU vary among mammalian species and among X-linked genes with distinct evolutionary origins [6].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for developing and validating cross-species foundation models

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational resources for cross-species foundation model research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | CZ CELLxGENE [9] [31] | Curated single-cell data with standardized annotations | Provides >100M unique cells; essential for pre-training |

| Tabula Sapiens [31] | Human scRNA-seq reference cell atlas | Used for evaluation with multiple donor IDs | |

| ZebraHub, GEO Accessions [31] | Species-specific single-cell data | Critical for cross-species generalization tests | |

| Computational Infrastructure | H100/A100 GPU Clusters [31] | Model training and inference | Memory-intensive; A100 40GB recommended for inference |

| DDP Training Framework [31] | Distributed training across multiple GPUs | Enables processing of trillion-token datasets | |

| Gene Reference Databases | ESM-2 Protein Embeddings [31] | Protein sequence-based gene representations | Provides biological context beyond expression |

| Homology Mapping Resources [29] | Orthologous gene identification across species | Critical for cross-species model integration | |

| Evaluation Benchmarks | scGraph-OntoRWR [5] | Cell ontology-informed metric | Measures biological relevance of embeddings |

| COVID-19 Lung Atlas [31] | Disease state classification benchmark | Tests infection response identification | |

| Multi-species Spermatogenesis Data [31] | Cross-species cell type annotation | Evaluates transfer learning across evolutionary distances |

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

The translational potential of cross-species foundation models extends significantly into drug development and biomedical research. These models enable more accurate translation of findings from model organisms to humans, which has historically been a major bottleneck in preclinical drug development [29] [6]. By identifying conserved cellular responses and pathways across species, researchers can prioritize drug targets with higher likelihood of translational success.

GeneCompass has demonstrated practical utility in identifying key factors associated with cell fate transitions, with experimental validation showing that predicted candidate genes could successfully induce the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into gonadal fate [29] [30]. This capability opens new avenues for regenerative medicine and cellular therapy development by accelerating the discovery of critical cell fate regulators.

TranscriptFormer's ability to identify disease states without fine-tuning presents significant opportunities for drug discovery [9] [31]. The model surpassed baseline models at identifying SARS-CoV-2-infected cells from non-infected cells in the COVID Lung atlas, demonstrating utility for predicting cellular infection states in datasets where infection status is unknown or difficult to determine experimentally [31]. This capability can help identify novel mechanisms of pathogenesis and cellular defense responses that serve as potential therapeutic targets.

Icebear facilitates drug development by enabling prediction of human disease responses from mouse models [6]. The framework has been shown to accurately predict transcriptomic alterations in human Alzheimer's disease versus control samples based on mouse data, enabling transfer of knowledge from single-cell profiles in mouse disease models to human contexts [6]. This approach can significantly reduce the time and cost of preliminary drug validation studies.

Benchmarking studies indicate that foundation models serve as robust plug-and-play modules for various downstream tasks in biomedical research [5]. Their zero-shot embeddings capture biological insights into the relational structure of genes and cells, which provides a foundation for tasks ranging from cancer cell identification to drug sensitivity prediction across multiple cancer types and therapeutic compounds [5].

Future Directions and Implementation Guidelines

The field of cross-species foundation models is rapidly evolving, with several important directions emerging for future development. A critical challenge is improving model interpretability to build trust in predictions and facilitate biological discovery [10] [5]. While current models demonstrate impressive performance, understanding the biological reasoning behind their predictions remains challenging. Future iterations may incorporate more explicit biological knowledge representation and mechanism-based reasoning.

Another important direction is the integration of multimodal data beyond transcriptomics [10] [31]. While current models primarily focus on single-cell RNA sequencing data, incorporating information from epigenomics (scATAC-seq), proteomics, spatial transcriptomics, and imaging would provide a more comprehensive understanding of cellular states and functions. TranscriptFormer's developers have indicated plans to iterate and develop new models that combine multiple modalities [9].

For researchers selecting and implementing these models, benchmarking studies provide crucial guidance [5]. The performance of foundation models is highly task-dependent, with no single model consistently outperforming others across all applications. Researchers should consider factors including dataset size, task complexity, biological interpretability requirements, and available computational resources when selecting a model [5].

Practical implementation requires careful attention to technical specifications. TranscriptFormer, for instance, recommends A100 40GB GPUs for efficient inference, though can operate on GPUs with as little as 16GB VRAM by reducing batch size [31]. The model variants are specialized for different use cases: TF-Metazoa for broad cross-species generalization, TF-Exemplar for human and major model organisms, and TF-Sapiens for human-only tasks [31].

As these models continue to evolve, they represent significant steps toward the ambitious goal of building comprehensive virtual cell models that can simulate cellular behavior across scales, time frames, and scientific modalities [9]. This capability would dramatically accelerate biomedical research by enabling computational experimentation and hypothesis testing prior to wet-lab validation, ultimately bringing scientists closer to curing, preventing, and managing human diseases.

This document details application notes and protocols for developing foundation models for cross-species cell annotation, focusing on self-supervised learning strategies applied to multi-species single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) corpora. The primary goal is to create models that learn fundamental biological principles conserved across evolution, enabling robust cell type identification and functional prediction across diverse species, including those not seen during training.

Table 1: Representative Models in Cross-Species Cell Annotation

| Model Name | Architecture | Training Corpus Scale | Number of Species | Key Demonstrated Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TranscriptFormer [9] | Transformer | 112 million cells [9] | 12 [9] | Cross-species cell type classification, disease state prediction, gene-gene interaction prompting |

| scTab [28] | Feature Attention Network | 22.2 million cells [28] | Human (cross-tissue) [28] | Scaling of performance with data and model size, cross-tissue annotation using data augmentation |

| Genomic Language Models (gLMs) [32] | Transformer-based | Varies (genome sequences) | Multiple [32] | Functional constraint prediction, sequence design, transfer learning |

Table 2: Key Performance Highlights from Featured Models

| Model / Experiment | Task | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|

| TranscriptFormer [9] | Cell type classification in out-of-distribution species (e.g., rhesus macaque, marmoset) | Able to identify cell types in species not included in its pre-training data [9] |

| TranscriptFormer [9] | Identification of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells | Surpassed baseline models at identifying infected from non-infected cells without fine-tuning [9] |

| scTab [28] | Cross-tissue cell type classification in human | Demonstrated that non-linear models outperform linear counterparts when trained at large scale [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Self-Supervised Pre-training of a Cross-Species Model

Objective: To train a transformer model on a large, evolutionarily diverse corpus of single-cell transcriptomics data to learn a foundational representation of cell states.

Materials:

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with multiple GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100 or H100).

- Software: Python 3.8+, PyTorch or JAX, Deep Graph Library (DGL) or PyTorch Geometric, Hugging Face Transformers library.

- Data: Curated multi-species single-cell data from resources like CZ CELLxGENE [9], Tabula Sapiens [9], and other public repositories.

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Harmonization:

- Collect scRNA-seq datasets from multiple species, covering a broad evolutionary distance (e.g., over 1.5 billion years) [9].

- Perform cross-species gene ortholog mapping to align gene features across different species' genomes. This creates a unified feature space for the model.

- Apply standard scRNA-seq preprocessing steps (quality control, normalization, and log-transformation) to the mapped count data.

Masked Language Model (MLM) Pre-training:

- The core self-supervised task is to train the model to predict randomly masked portions of a cell's gene expression vector [32] [9].

- For each cell in a training batch, randomly mask a subset (e.g., 15%) of the gene expression values.

- Feed the corrupted gene expression vector into the transformer encoder.

- The model's objective is to reconstruct the original, uncorrupted expression values for the masked genes.

- Use a loss function like Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the predicted and actual expression values.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Utilize a standard Transformer encoder architecture [9]. The input is the gene expression vector, and the model outputs a reconstructed vector.

- Train the model using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate schedule (e.g., cosine decay) for a large number of steps (e.g., hundreds of thousands).

- Implement gradient checkpointing and mixed-precision training to manage memory usage and accelerate training on large corpora.

Protocol: Zero-Shot Cross-Species Cell Type Annotation

Objective: To leverage a pre-trained model to annotate cell types in a species that was not part of the training set, without any further fine-tuning.

Materials:

- A model pre-trained using Protocol 2.1 (e.g., TranscriptFormer) [9].

- Query dataset of scRNA-seq profiles from a new species with unknown cell labels.

Procedure:

- Data Projection:

- Process the query dataset through the pre-trained model to generate an embedding (a numerical representation) for each cell.

Reference-Based Annotation:

- Identify a curated reference atlas from a phylogenetically related species that has well-annotated cell types.

- Generate embeddings for all cells in this reference atlas using the same pre-trained model.

- For each cell in the query dataset, find the k-nearest neighbors (e.g., using cosine similarity) among the reference cell embeddings.

- Transfer the cell type label from the majority vote of the nearest neighbors in the reference to the query cell.

Validation:

- If a manually annotated version of the query dataset exists, use it to calculate metrics like accuracy to benchmark the model's zero-shot performance.

Protocol: In-silico Gene Perturbation via Prompting

Objective: To use the pre-trained generative model to simulate the transcriptomic outcome of a gene knockout or overexpression.

Materials:

- A pre-trained generative model like TranscriptFormer [9].

Procedure:

- Model Prompting:

- Input a cell's gene expression vector into the model.

- To simulate a knockout, mask the expression value of the target gene.

- To simulate overexpression, artificially elevate the input value of the target gene.

- Prediction and Analysis:

- Allow the model to generate the predicted full gene expression profile of the cell given the perturbation.

- Compare the predicted profile to the original, unperturbed profile.

- Analyze the differentially expressed genes to hypothesize the downstream effects and functional consequences of the perturbation.

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Cross-Species Cell Atlas Research

| Resource / Solution | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|