Decoding Cell Therapy Mechanisms of Action: From Biological Principles to Clinical Application and Regulatory Strategy

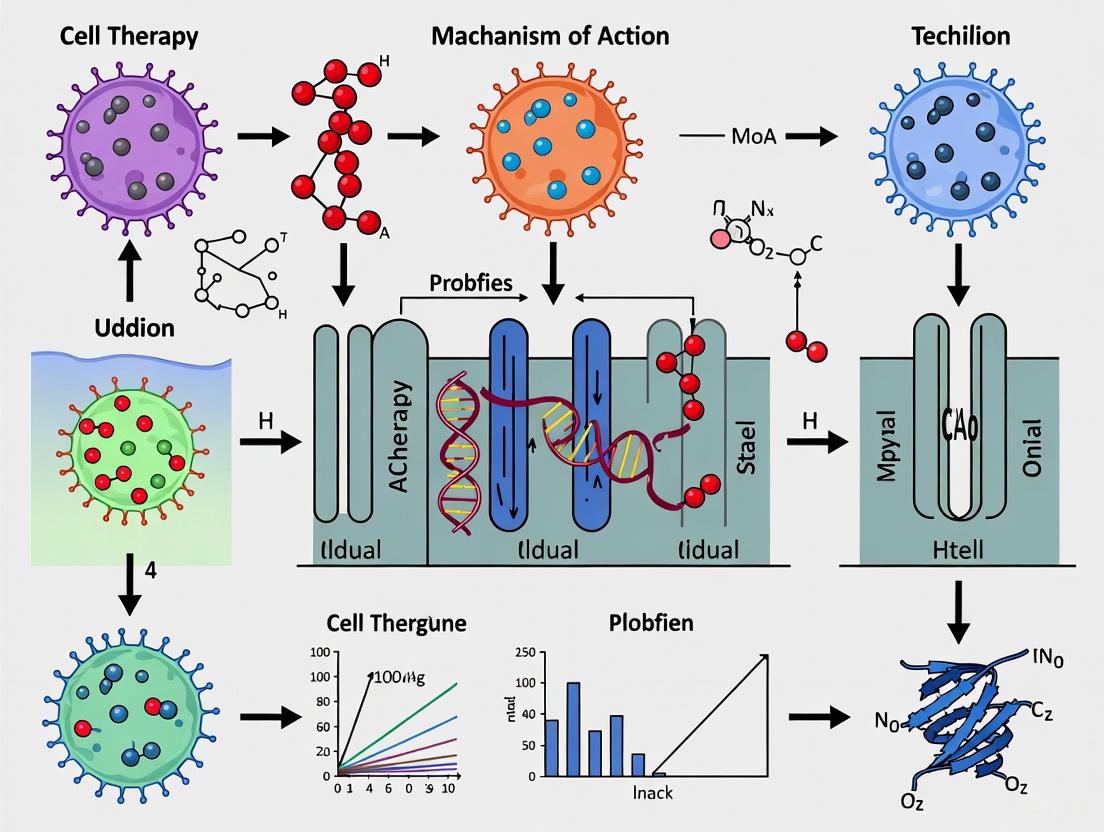

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cell therapy mechanisms of action (MoA) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Decoding Cell Therapy Mechanisms of Action: From Biological Principles to Clinical Application and Regulatory Strategy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cell therapy mechanisms of action (MoA) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology of diverse cell modalities, including CAR-T, TCR-T, TIL, and emerging NK cell therapies, detailing their distinct functional principles. The content delves into methodological frameworks for MoA-aligned analytical development and potency testing, addressing common challenges in clinical translation and manufacturing. It further examines troubleshooting strategies for optimization and the critical role of MoA validation in regulatory success, incorporating insights from recent FDA approvals and global regulatory landscapes. This resource synthesizes current scientific understanding with practical development considerations to advance effective and compliant cell therapy programs.

The Cellular Arsenal: Deconstructing Fundamental Mechanisms of Action in Modern Therapies

Defining Mechanism of Action (MoA) in the Context of Complex Cell Therapy Products

For researchers and drug development professionals in the cell therapy space, defining a product's Mechanism of Action (MoA) represents both a scientific necessity and a regulatory requirement. Unlike small molecule drugs with well-defined target engagement, cell therapies exhibit complex, often multifaceted biological activities that present unique characterization challenges. The MoA specifically refers to "the specific process, often pharmacologic, through which a product produces its intended effect" [1]. Understanding MoA is particularly crucial for Complex Cell Therapy Products such as CAR-Ts, TCR-Ts, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), where the biological activity cannot be fully described by a single parameter.

Regulatory agencies consider potency—the attribute that enables a product to achieve its intended MoA—a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) that must be measured for each lot to ensure the therapy will have its intended clinical effect [2]. This review examines current approaches to MoA determination for cell therapies, compares methodologies across different product types, and provides practical experimental frameworks to advance product characterization.

The MoA-Potency-Efficacy Framework in Cell Therapies

Conceptual Distinctions and Relationships

A fundamental challenge in cell therapy development lies in properly distinguishing between three interconnected concepts: MoA, potency, and efficacy. According to regulatory guidelines and metrological principles [1]:

- Mechanism of Action (MoA): The specific biological process through which a product produces its intended therapeutic effect

- Potency: The attribute of a product that enables it to achieve its intended MoA (a laboratory-measured CQA)

- Efficacy: The ability of the product to have the desired effect in patients (a clinical outcome)

These relationships can be visualized through the following potency and efficacy process charts adapted from regulatory science frameworks [1]:

Regulatory Significance of MoA Determination

For the 27 FDA-approved cell therapy products (as of February 2024), the relationship between MoA and potency assays shows considerable variability [1]. Regulatory documentation reveals that:

- For Provenge, Gintuit, MACI and Amtagvi, the MoA is explicitly stated as not known

- For Kymriah, regulators noted difficulty correlating potency test results with efficacy

- For Rethymic and Lantidra, documentation uses tentative language ("proposed," "believed") when discussing MoA

This uncertainty underscores the challenge in definitively establishing MoA for complex cell products. Despite this, regulators require potency tests based on the proposed or theoretical MoA, recognizing that complete understanding may evolve as clinical experience accumulates.

Comparative MoA Analysis Across Cell Therapy Modalities

Established vs. Emerging Cell Therapy Modalities

The global cell therapy landscape encompasses both established and emerging modalities with varying levels of MoA understanding. According to BCG's 2025 analysis of new drug modalities [3]:

Table 1: Growth Trends and MoA Understanding Across Cell Therapy Modalities

| Modality | Growth Trend | Level of MoA Understanding | Primary Therapeutic Applications | Key Challenges in MoA Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR-T Therapies | Robust growth | Moderate | Hematologic malignancies, expanding to autoimmune diseases | Cytokine release dynamics, long-term persistence mechanisms |

| TCR-T Therapies | Emerging (first approval in 2024) | Low-Moderate | Solid tumors (e.g., synovial sarcoma) | MHC-restricted recognition, tumor microenvironment interactions |

| TIL Therapies | Emerging (first approval in 2024) | Low | Solid tumors | Polyclonal specificity, migration and infiltration mechanisms |

| Stem Cell Therapies | Mixed results | Low | GVHD, regenerative applications | Differentiation cascades, paracrine signaling mechanisms |

| CAR-NK Therapies | Declining interest | Low | Hematologic malignancies | Multiple killing mechanisms, limited persistence |

MoA-Based Classification of Approved Cell Therapies

Analysis of regulatory documentation for approved cell therapies reveals distinct patterns in MoA characterization [1]:

Table 2: MoA Characterization Patterns in FDA-Approved Cell Therapies

| MoA Characterization Pattern | Representative Products | Regulatory Language | Implications for Potency Assay Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicitly Unknown MoA | Provenge, Gintuit, MACI, Amtagvi | "Mechanism of action is not known" | Focus on descriptive potency assays measuring outputs rather than mechanistic understanding |

| Proposed/ Theoretical MoA | Rethymic, Lantidra | "MOA is believed to involve...", "Proposed mechanism..." | Mechanism-informed potency assays with acknowledgment of uncertainty |

| Partially Characterized MoA | Kymriah, Yescarta | Description of specific pathways with noted limitations | Multi-parametric potency assays addressing known mechanisms |

| Correlation Challenges | Multiple CAR-T products | "Difficult to correlate potency test with efficacy" | Development of biomarker matrices rather than single potency measures |

Experimental Approaches for MoA Determination

Integrated Workflow for MoA Establishment

Establishing MoA for cell therapies requires an iterative approach spanning nonclinical and clinical development stages. The following workflow outlines key experimental components:

Methodological Details for Key MoA Experiments

Cytokine Secretion Profiling (CAR-T Example)

Objective: Quantify effector function through cytokine release upon target engagement [1] [2].

Protocol:

- Co-culture Establishment: Plate target cells (tumor cell lines or artificial antigen-presenting cells) at optimized density

- Effector Cell Addition: Add CAR-T cells at predetermined effector:target ratios (typically 1:1 to 10:1)

- Incubation: Culture for 16-24 hours under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂)

- Supernatant Collection: Remove culture supernatant without disturbing cells

- Multiplex Cytokine Analysis: Quantify IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, Granzyme B using Luminex or ELISA

- Data Normalization: Express results as cytokine release per cell or per co-culture unit

Key Controls:

- Effector cells alone (background secretion)

- Target cells alone (baseline cytokine production)

- Positive control (PMA/ionomycin stimulation)

- Negative control (non-specific target cells)

Target Cell Killing Assays

Objective: Measure direct cytotoxic capacity through real-time and endpoint measurements [2].

Protocol Options:

- Real-time Cytotoxicity: Incubate effector and target cells in ratio-dependent manner with continuous monitoring of cell viability using impedance-based systems (xCELLigence)

- Flow Cytometry-Based Killing: Use dye-labeled target cells (CFSE, CellTrace) with viability dyes (propidium iodide, 7-AAD) to quantify specific killing

- Luciferase-Reporter Assays: Employ engineered target cells expressing luciferase; measure luminescence decrease as indicator of killing

Critical Parameters:

- Effector:Target ratio optimization

- Timing of measurement (early vs. late timepoints)

- Assay linearity and dynamic range

Research Reagent Solutions for MoA Studies

Essential Tools for Cell Therapy MoA Characterization

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MoA Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Considerations for Assay Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Target Cells | Custom cell mimics (e.g., TruCytes), Engineered cell lines | Provide consistent antigen presentation for potency assays | Documented lineage, genetic stability, antigen expression consistency |

| Cytokine Detection Kits | Multiplex Luminex panels, ELISA kits, ELISpot kits | Quantify effector function and immune modulation | Standard curve performance, sensitivity, dynamic range, cross-reactivity |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays | Real-time impedance systems, flow cytometry with viability dyes, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release | Measure direct target cell killing | Linearity with cell number, compatibility with cell types, interference from media components |

| Cell Tracking Reagents | CFSE, CellTrace dyes, luciferase/GFP reporters | Monitor cell proliferation, persistence, and trafficking | Dye transfer concerns, effects on cell function, signal stability |

| Magnetic Selection Kits | CD3/CD28 beads, cell separation kits | Standardize cell populations for consistent starting material | Purity, recovery, and functional effects on selected cells |

Case Studies: MoA Challenges and Solutions

Kymriah (Tisagenlecleucel): Correlation Challenges

The first FDA-approved CAR-T therapy exemplifies the challenge of correlating potency measurements with clinical outcomes. Kymriah's potency is defined as the ability of CAR T-cells to secrete interferon-γ (IFN-γ) following exposure to CD19-expressing target cells [1]. However, FDA documentation states: "In the clinical trials, IFN-γ production varied greatly from lot-to-lot, making it difficult to correlate IFN-γ production in vitro with tisagenlecleucel safety or efficacy" [1].

Analysis of clinical data revealed:

- Correlation with remission but significant overlap between responders and non-responders

- Multi-parametric assessment needed beyond single cytokine measurement

- Patient-specific factors influence potency-efficacy relationship

Emerging Solutions: Multi-Assay Potency Matrices

For products with complex or incompletely understood MoAs, the field is moving toward multi-parametric potency matrices rather than single-parameter tests. The case of Iovance's TIL therapy (lifileucel) demonstrates this approach [2]:

- Initial setback: FDA requested additional potency data beyond single-assay approach

- Solution implemented: Multi-assay matrix including functional co-culture assays

- Outcome: After multi-year delay, comprehensive potency strategy supported approval

This case underscores that regulators increasingly expect mechanism-relevant potency assays that collectively reflect the complex biological activity of cell therapies, even when complete MoA understanding remains elusive.

Defining Mechanism of Action for complex cell therapy products remains challenging yet essential for product characterization and regulatory approval. The evolving landscape suggests several strategic imperatives for researchers and developers:

- Embrace Mechanistic Complexity: Recognize that cell therapies may function through multiple parallel mechanisms rather than single pathways

- Invest Early in Potency Assay Development: Begin MoA-informed potency assessment during preclinical development to avoid delays later [2]

- Implement Multi-Parametric Approaches: Develop potency matrices that collectively reflect biological activity when single-parameter tests are insufficient

- Leverage Advanced Analytical Tools: Utilize omics technologies, single-cell analysis, and computational modeling to deconvolute complex mechanisms

As the field advances from hematologic malignancies to solid tumors and autoimmune diseases, understanding MoA will grow in importance for designing safer, more effective cell therapies. The frameworks, methodologies, and comparative analyses presented here provide a foundation for advancing MoA research in this rapidly evolving field.

The field of cancer immunotherapy has been revolutionized by strategies that redirect the patient's own T cells to recognize and eliminate tumor cells. Among the most advanced of these are Chimeric Antigen Receptor T (CAR-T) cells and T-cell Engagers (TCEs). Although both modalities share the ultimate goal of achieving potent, targeted tumor cell killing, they represent fundamentally different technological approaches. CAR-T therapy involves the ex vivo genetic engineering of a patient's T cells to express synthetic receptors that target tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), effectively creating a "living drug" [4] [5]. In contrast, TCEs are typically bispecific antibody-derived molecules that act as a physical bridge between a T cell (via CD3) and a tumor cell (via a TAA), redirecting existing T cell cytotoxicity without requiring genetic modification [6] [7] [8]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of their mechanisms of action, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to cell therapy research and development.

Mechanism of Action: A Comparative Analysis

CAR-T Cell Mechanism: Genetically Engineered Living Drugs

CAR-T cells are generated by genetically modifying patient-derived T cells to express a chimeric antigen receptor. The canonical CAR is a synthetic receptor comprising an extracellular antigen-recognition domain (often a single-chain variable fragment, or scFv, derived from a monoclonal antibody), a hinge region, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain [4] [5]. Upon binding to a surface antigen on a tumor cell, the CAR initiates T cell activation independently of the native T cell receptor (TCR) and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation, a key differentiator from physiological T cell activation [9].

The signaling cascade leads to:

- Cytolytic Granule Release: Perforin and granzymes are released at the immune synapse, inducing apoptosis in the target tumor cell [4] [8].

- Cytokine Production: Inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 are secreted, amplifying the immune response [5].

- T cell Proliferation and Clonal Expansion: The activated CAR-T cell undergoes rapid division, increasing the number of effector cells [4].

A critical limitation of first-generation CARs was suboptimal persistence. This was addressed in subsequent generations by incorporating costimulatory domains (e.g., CD28 or 4-1BB) alongside the CD3ζ activation domain, which enhance T cell survival, proliferation, and sustained antitumor activity [4] [5].

Figure 1: CAR-T Cell Activation Pathway. Antigen binding initiates a synergistic signaling cascade leading to full T-cell activation.

T-cell Engager Mechanism: Bispecific Bridging Molecules

TCEs are engineered proteins, most often bispecific antibodies, designed to simultaneously bind to the CD3ε subunit of the TCR complex on T cells and a TAA on cancer cells [6] [7]. This forced proximity creates an immunological synapse that triggers T cell activation and cytotoxic killing of the bound tumor cell, entirely independently of the T cell's intrinsic TCR specificity [8].

Key functional characteristics of TCEs are dictated by their structural design:

- Format: They range from small, fragment-based constructs like Bispecific T-cell Engagers (BiTEs) to full-length IgG-like antibodies that may include an Fc region [6] [7].

- Fc Domain Impact: The presence of an Fc region can confer a longer half-life but may also limit tissue penetration and contribute to adverse events via Fc receptor interactions [6] [8].

- Avidity Engineering: Newer formats like "2+1" TCEs (two tumor-binding domains, one CD3-binding domain) leverage avidity to improve selectivity for tumor cells with high antigen density, potentially reducing on-target, off-tumor toxicity [7].

A significant advantage of TCEs is their ability to recruit any available T cell, irrespective of its native specificity, making them an "off-the-shelf" therapeutic that does not require complex personalization [5].

Figure 2: T-cell Engager Bispecific Bridging. The TCE physically links a T cell and a tumor cell, inducing targeted cytotoxicity.

Direct Comparison of Functional Performance

Understanding the functional differences between these two modalities is critical for research and clinical development. The table below synthesizes key characteristics based on the literature.

Table 1: Functional and Operational Comparison of CAR-T Cells and T-cell Engagers

| Feature | CAR-T Cells | T-cell Engagers (TCEs) |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Type | Living, genetically engineered cells | Bispecific antibody molecules |

| Mechanism | Endogenous expression of synthetic antigen receptor | Extracellular bridge between CD3 and TAA |

| MHC Restriction | No [4] | No [8] |

| Antigen Recognition | Surface antigens only [4] | Primarily surface antigens; TCR-based formats can target peptide-MHC [6] |

| Requirement for Costimulation | Incorporated into CAR design (2nd gen+) [5] | Generally not required [8] |

| Pharmacokinetics | Single infusion, potential for long-term persistence | Short half-life (fragment-based); longer with Fc/HSA binding [6] [7] |

| Manufacturing | Complex, patient-specific, ex vivo process; time-intensive [5] | Off-the-shelf, industrial biologics production; simpler scale-up [5] |

A critical functional difference lies in their response to varying levels of antigen exposure. A 2022 study directly comparing CD20-targeting CAR-T cells and engineered TCR (eTCR) T cells (a modality with similarities to TCEs in being TCR-dependent) revealed divergent performance under high antigenic pressure [10].

Table 2: Performance as a Function of Antigen Exposure (Based on Ref [10])

| Performance Metric | CAR-T Cells | eTCR T Cells (TCR-Dependent) |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Term Potency | Higher cytotoxicity and cytokine production | Lower cytotoxicity and cytokine production |

| Expansion under High Antigen | Significantly impaired | Robust |

| Phenotype under High Antigen | Elevated exhaustion markers (e.g., coinhibitory molecules), effector differentiation | Lower exhaustion markers, maintenance of early differentiation phenotype |

| Long-Term Tumor Clearance | Compromised by exhaustion | Comparable, sustained clearance |

This data suggests that while CAR-T cells can initiate a more potent immediate response, their activation signaling—which differs from physiological TCR signaling—may predispose them to exhaustion in environments with high tumor burden [10] [9]. In contrast, TCR-dependent mechanisms appear to support better long-term expansion and persistence under the same conditions.

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Studies

For scientists dissecting the MoA of these therapies, the following core experimental methodologies are foundational.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

This assay quantitatively measures the ability of CAR-T cells or TCEs to kill specific target cells.

Protocol Outline:

- Effector and Target Cell Preparation: Prepare CAR-T cells or unmodified T cells (for TCE testing) as effector cells. Harvest tumor cells expressing the target antigen as target cells.

- Target Cell Labeling: Label target cells with a fluorescent dye such as calcein-AM or a membrane-labeling dye (e.g., PKH67). Alternatively, use tumor cells engineered to express a luciferase or GFP reporter.

- Co-culture Setup: Plate target cells in a multi-well plate and add effector cells at varying Effector:Target (E:T) ratios. For TCE testing, add the bispecific molecule at a range of concentrations to wells containing T cells and target cells. Include controls for spontaneous and maximum target cell lysis.

- Incubation: Incubate for a predetermined period (e.g., 4-24 hours) at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Lysis Measurement:

- For calcein-AM: Measure fluorescence in the supernatant (released from lysed cells).

- For luciferase: Lyse all cells and measure luminescence; specific lysis is inversely proportional to signal.

- For flow cytometry: Use a viability dye or count residual target cells via specific markers.

- Data Analysis: Calculate percent-specific lysis:

% Lysis = (Experimental - Spontaneous) / (Maximum - Spontaneous) * 100[5].

Cytokine Release Analysis

This protocol assesses T cell activation by quantifying secreted cytokines, which is also a key safety biomarker for Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS).

Protocol Outline:

- Stimulation: Co-culture effector cells (CAR-T or unmodified T cells) with antigen-positive target cells in the presence or absence of TCEs, as appropriate.

- Supernatant Collection: Collect cell culture supernatant at various time points post-stimulation (e.g., 6, 24, 48 hours).

- Cytokine Quantification:

- ELISA: The traditional method for quantifying specific cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, IL-6) using paired antibodies. Provides absolute concentration.

- Multiplex Bead Array (e.g., Luminex): Allows simultaneous quantification of dozens of cytokines from a small sample volume. This is efficient for profiling.

- Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS) with Flow Cytometry: Can identify which specific T cell subsets are producing cytokines by using protein transport inhibitors to accumulate cytokines intracellularly, followed by staining and flow analysis [5] [11].

Immune Synapse Characterization

Advanced microscopy techniques are used to visualize and quantify the structure of the immune synapse formed during CAR- or TCE-mediated engagement.

Protocol Outline:

- Synapse Formation: Allow effector and target cells to interact in the presence of the engaging molecule on a coated surface (e.g., poly-L-lysine) for a short period (minutes).

- Fixation and Staining: Fix cells with paraformaldehyde, permeabilize if needed, and stain with fluorescently labeled antibodies.

- Key Staining Targets: CAR or TCR (if applicable), CD3, the target antigen, actin cytoskeleton (phalloidin), and key signaling molecules (e.g., phosphorylated proteins).

- High-Resolution Imaging: Acquire images using Confocal Microscopy or Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) Microscopy. TIRF is particularly useful for visualizing events at the cell membrane contact zone.

- Image Analysis: Analyze images for synaptic characteristics:

- Synapse Architecture: Assess the organization of key molecules into canonical structures like the central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC). CAR synapses are often noted to be more disorganized than TCR synapses [9].

- Molecular Polarization: Quantify the recruitment of cytotoxic granules and signaling proteins to the contact site.

- Synapse Stability: Measure the duration of the cell-cell contact [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CAR-T and TCE Mechanism of Action Research

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3 Antibodies | T cell activation and validation | Positive control for TCE assays; component of T cell culture [5] |

| Recombinant TCE Molecules | Bispecific engagement | In vitro and in vivo proof-of-concept studies; potency assays [7] |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Stable gene delivery | Standard tool for engineering CAR expression in T cells [4] [5] |

| Cell Trace Proliferation Dyes | Tracking cell division | Monitoring CAR-T or engaged T cell proliferation (e.g., CFSE, CellTrace Violet) [11] |

| Multiplex Cytokine Assays | Profiling immune secretion | Assessing T cell activation potency and safety (CRS potential) [11] |

| pMHC Multimers | Identifying antigen-specific T cells | Validating TCR-based therapeutics and monitoring responses [12] |

CAR-T cells and T-cell Engagers are two powerful pillars of redirected T cell immunotherapy with distinct and complementary profiles. CAR-T cells offer the potential for a single-administration, living therapy capable of long-term persistence and surveillance, making them highly effective in certain hematologic malignancies. However, their complex, personalized manufacturing and propensity for exhaustion in high-burden environments remain significant challenges. TCEs, as off-the-shelf biologics, offer immediate logistical and economic advantages and can effectively recruit diverse T cell populations without prior activation. Their main challenges include managing toxicities like CRS and optimizing pharmacokinetics. The choice between these modalities, or their potential sequential or combined use, will depend on the specific clinical context, tumor type, and antigen landscape. Future research will focus on engineering next-generation products that enhance efficacy, safety, and applicability to solid tumors.

The challenge of treating solid tumors has catalyzed the development of advanced cellular immunotherapies, with Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) and T-cell receptor-engineered T-cell (TCR-T) therapies emerging as two prominent strategies. While both approaches harness the cytotoxic potential of T lymphocytes to eliminate cancer cells, they fundamentally differ in their recognition mechanisms—TILs utilize naturally selected native receptors, whereas TCR-T cells employ genetically engineered receptors for enhanced specificity [13] [14]. This distinction profoundly impacts their antigen recognition breadth, manufacturing complexity, and clinical application. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals optimizing cell therapy mechanisms of action. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these platforms, focusing on their recognition mechanisms, experimental data, and methodological protocols to inform therapeutic development decisions.

Mechanisms of Action: Native Polyclonality vs. Engineered Precision

TIL Therapy: Native Recognition of Tumor Neoantigens

TIL therapy leverages the body's natural immune response by isolating T cells that have already infiltrated a patient's tumor [15] [16]. These cells are expanded ex vivo and reinfused to enhance anti-tumor immunity. The therapeutic efficacy of TILs stems from their native T cell receptors (TCRs), which naturally recognize tumor-specific neoantigens—abnormal proteins resulting from somatic mutations in tumor cells [15].

- Polyclonal Recognition: TIL products contain multiple T-cell clones with diverse TCRs capable of recognizing a broad array of tumor antigens simultaneously, effectively addressing tumor heterogeneity [15] [14].

- Neoantigen Targeting: The native TCRs in TILs predominantly target mutation-derived neoepitopes, which are uniquely expressed on tumor cells, minimizing off-tumor toxicity [15] [17].

- Mechanism of Action: TILs recognize intracellular and surface antigens processed and presented as peptides by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on tumor cells [13]. This recognition initiates cytotoxic killing through perforin/granzyme release and cytokine secretion [18].

TCR-T Therapy: Engineered Recognition for Enhanced Specificity

TCR-T therapy involves genetically modifying a patient's peripheral blood T cells to express synthetic TCRs specifically selected for their high affinity against predefined tumor antigens [13] [19]. Unlike TILs, TCR-T cells are monoclonal or oligoclonal, targeting a limited set of carefully selected antigens.

- Precision Engineering: TCR-T cells are engineered to recognize specific intracellular antigens, such as viral oncoproteins or cancer-testis antigens, presented by MHC molecules [13] [19].

- MHC-Dependent Recognition: Like TILs, TCR-T cells require MHC presentation for antigen recognition, enabling targeting of intracellular proteins not accessible to other modalities like CAR-T [20].

- Enhanced Specificity Protocols: Advanced screening platforms identify high-affinity TCRs against defined neoantigens, with genetic screening approaches demonstrating superior sensitivity compared to conventional flow cytometry-based methods [17].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in the recognition pathways for TIL and TCR-T therapies:

Comparative Clinical Performance and Experimental Data

Clinical data demonstrate distinct response patterns for TIL and TCR-T therapies across different solid tumor indications. The following table summarizes key efficacy metrics from recent studies and trials.

Table 1: Clinical Response Comparison for TIL and TCR-T Therapies

| Therapy | Cancer Indications | Response Rates | Response Durability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIL Therapy [15] [16] [21] | Melanoma | 31.5%-41% ORR (Objective Response Rate) | 43.5% maintained remission >12 months; Decade-long remissions reported | Limited to immunogenic tumors; Labor-intensive manufacturing |

| Cervical Cancer | 30-35% ORR | Durable responses observed | Requires high TMB (Tumor Mutational Burden) | |

| NSCLC (Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer) | 20-30% ORR | Ongoing responses >2 years | Heterogeneous response across patients | |

| TCR-T Therapy [21] [19] | HPV-associated Cancers (Phase 2 trial) | 60% ORR (6/10 patients; 2 CR, 4 PR) | Ongoing CR (Complete Response) at 12-14 months | HLA restriction limited to specific alleles |

| Solid Tumors (Preclinical) | Target-dependent variability | Requires persistent antigen exposure | Off-target toxicity concerns |

Analysis of Clinical Performance Patterns

TIL therapy demonstrates broader applicability across multiple solid tumor types, with particularly robust response rates in immunologically "hot" tumors like melanoma and cervical cancer [15] [16]. The polyclonal nature of TILs enables targeting of multiple neoantigens simultaneously, potentially overcoming tumor heterogeneity [14]. Notably, decade-long complete remissions have been reported in metastatic cervical cancer patients, suggesting the potential for curative outcomes in selected cases [21].

TCR-T therapy shows remarkable precision in defined patient populations, as evidenced by the 60% objective response rate in HPV-associated cancers [21] [19]. The complete responses observed in this trial, ongoing at 12 and 14 months, demonstrate the potential of engineered receptors to mediate durable anti-tumor activity. However, this approach requires careful patient selection based on HLA haplotypes and specific antigen expression [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Approaches

TIL Therapy Manufacturing and Expansion Protocols

TIL therapy relies on complex manufacturing processes to expand tumor-derived T cells while maintaining their anti-tumor reactivity.

Standard TIL Protocol [15] [16]:

- Tumor Resection: Surgical removal of tumor tissue (1-2 cm³)

- TIL Extraction: Mechanical and enzymatic digestion to dissociate tissue and isolate lymphocytes

- Rapid Expansion: Culture with IL-2 (6000 IU/mL) for 2-3 weeks

- REP (Rapid Expansion Protocol): Stimulation with anti-CD3 antibody and irradiated feeder cells

- Lymphodepletion: Patient preconditioning with cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg/d × 2d) and fludarabine (25 mg/m²/d × 5d)

- TIL Infusion: Administration of expanded cells (10¹⁰ to 10¹¹ cells)

- IL-2 Support: Post-infusion IL-2 administration (720,000 IU/kg every 8-12 hours)

Young TIL Protocol [15]: This modified approach reduces manufacturing time to approximately 20 days by omitting the initial tumor reactivity screening. Young TILs exhibit superior characteristics including longer telomeres and increased CD27/CD28 expression, correlating with improved persistence post-infusion.

TCR-T Discovery and Engineering Platforms

Advanced screening technologies enable identification of high-affinity TCRs for therapeutic engineering.

High-Throughput TCR Discovery Platform [17]:

- Tumor Sequencing: Whole exome and RNA sequencing of tumor biopsies to identify mutations

- Neoantigen Prediction: In silico prediction of HLA-binding neoantigen peptides

- Library Construction: Synthesis of tandem minigene (TMG) libraries encoding 12 neoantigens flanked by LAMP1 sequences for enhanced MHC class II presentation

- Combinatorial TCR Library: Assembly of all possible TCRα and TCRβ chain combinations from TIL sequencing data

- Functional Screening: Pooled TCR library transduction into Jurkat reporter T cells followed by co-culture with autologous antigen-presenting cells (APCs)

- Activation-Based Sorting: Isolation of CD69-high T cells via FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting)

- TCR Identification: Next-generation sequencing of enriched TCR sequences

Optimized Antigen Presentation System [17]: The platform utilizes immortalized autologous B cells as APCs, engineered to express BCL-6/BCL-xL for expansion and CD40L for enhanced antigen presentation. This system supports both HLA class I and II restricted antigen presentation, enabling comprehensive TCR screening.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key methodological differences between TIL and TCR-T development:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of TIL and TCR-T research requires specialized reagents and platforms. The following table details essential research tools for investigating these cellular therapies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for TIL and TCR-T Investigations

| Research Tool | Application | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 (Interleukin-2) [15] [16] | TIL Expansion | T cell growth and activation | Culture at 6000 IU/mL for 2-3 weeks |

| Anti-CD3 Antibody [15] | TIL REP (Rapid Expansion Protocol) | TCR stimulation for rapid proliferation | Used with irradiated feeder cells |

| Lymphodepletion Agents [15] [21] | Patient Preconditioning | Create immune space for infused cells | Cyclophosphamide + fludarabine regimen |

| Tandem Minigene (TMG) Libraries [17] | TCR Discovery | Express neoantigen panels for screening | TMG12 design with LAMP1 sequences |

| Immortalized B Cells [17] | Antigen Presentation | Autologous APCs for TCR screening | Engineered with BCL-6/BCL-xL and CD40L |

| Jurkat Reporter Cells [17] | TCR Functional Screening | Monitor TCR activation via CD69 expression | CD8+ TCR KO Jurkat with NFAT-GFP |

| Oxford Nanopore Sequencing [17] | TCR Identification | Characterize paired TCRαβ chains from libraries | PCR/ONT sequencing with optimized filtering |

| G-Rex Flasks [15] | Large-Scale TIL Expansion | Gas-permeable culture vessels | Enable 2310-fold cell expansion |

| Microbubble Technology [20] | T Cell Separation | Gentle, buoyancy-based cell isolation | Akadeum's BACS for T cell enrichment |

TIL and TCR-T therapies represent complementary approaches in the solid tumor immunotherapy landscape, each with distinct advantages for specific research and clinical contexts. TIL therapy offers a polyclonal, native recognition system capable of targeting multiple tumor antigens simultaneously, making it particularly suitable for immunologically "hot" tumors with high mutational burden [15] [16]. The decade-long complete remissions observed in metastatic cervical cancer patients highlight its potential for achieving durable responses [21]. Conversely, TCR-T therapy provides a precision medicine approach with defined antigen specificity, demonstrating remarkable efficacy in virally-associated cancers and situations where target antigens are well-characterized [21] [19].

The choice between these platforms depends on multiple factors including tumor immunogenicity, antigen availability, manufacturing capabilities, and desired specificity. For research applications focused on discovering novel tumor antigens or targeting heterogeneous malignancies, TIL-based approaches provide a comprehensive discovery platform. For targeted intervention against defined oncogenic drivers, TCR-T platforms offer precise engineering solutions. As both fields advance, convergence of these technologies—such as applying TCR engineering principles to enhance TIL specificity—may yield next-generation therapies with optimized recognition capabilities for solid tumor treatment.

Natural Killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes of the innate immune system that play a critical role in rapidly recognizing and eliminating abnormal, virally infected, and tumor cells without prior sensitization [22]. Their unique biological properties position them as compelling candidates for cell therapy, particularly due to mechanisms of action (MoA) that diverge significantly from T-cell-based approaches. Unlike T-cell activation, which is governed by antigen-specific T-cell receptors requiring major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation, NK cell stimulation is regulated by a complex balance of activating and inhibitory receptors that operate independently of antigen processing or presentation [22]. This innate recognition capability, coupled with their capacity to modulate immunity through cytokine secretion, underscores their pivotal role in orchestrating immune responses within tumor microenvironments (TME) [22]. The therapeutic application of NK cells represents a paradigm shift in cell therapy MoA research, leveraging innate immunity's speed and flexibility while overcoming limitations of adaptive immunity approaches.

Biological Mechanisms: Innate Recognition and Cytotoxic Pathways

Fundamental NK Cell Biology

NK cells exert their primary cytotoxic functions through several distinct biological mechanisms that operate in concert. Their defining feature is the ability to detect and eliminate target cells through integrated signaling from multiple surface receptors [23]. The "missing-self" hypothesis, proposed in 1986, explains one fundamental NK cell MoA: the recognition and elimination of cells that have lost MHC class I expression, a common occurrence in cancerous or virally infected cells attempting to evade T-cell immunity [23]. This capability provides a complementary mechanism to T-cell responses, targeting pathological cells that might otherwise escape adaptive immune surveillance.

NK cells perform target cell killing primarily through the release of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes [22] [23]. Perforin forms pores (~16 nm inner diameter) in the target cell membrane, facilitating the delivery of proteolytic granzymes that activate caspase-mediated apoptosis [23]. Additionally, NK cells express death receptors such as FasL and TRAIL, which can induce programmed cell death through extrinsic apoptosis pathways [23]. A third key mechanism is antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), mediated through CD16 (FcγRIII) receptors that recognize antibody-coated target cells [23]. This versatile arsenal enables NK cells to rapidly eliminate diverse threats through multiple parallel pathways.

Receptor Signaling and Activation Dynamics

NK cell activity is governed by a sophisticated integration of signals from activating and inhibitory receptors. Major activating receptors include NKG2D (binds to MICA, MICB, ULBP), natural cytotoxicity receptors (NKp30, NKp44, NKp46), and DNAM-1 [23]. Inhibitory receptors, primarily killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) and NKG2A, recognize MHC class I molecules on healthy cells, providing a crucial "off" signal that prevents autoimmunity [23]. The transition from inhibition to activation occurs when activating signals overwhelm inhibitory inputs, typically when target cells display stress-induced ligands while downregulating MHC class I.

Table 1: Key NK Cell Receptors and Their Functions in Tumor Immunity

| Receptor | Type | Ligand(s) | Signaling Pathway | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NKG2D | Activating | MICA, MICB, ULBP, Rae-1 | DAP10 | Recognizes stress-induced ligands on tumor cells |

| NKp30 | Activating | B7-H6, BAT3 | CD3ζ, FcεRIγ | Natural cytotoxicity against transformed cells |

| NKp46 | Activating | Complement factors, viral hemagglutinins | CD3ζ, FcεRIγ | Primary natural cytotoxicity receptor |

| KIRs | Inhibitory | MHC class I | ITIM domains | Prevents killing of healthy self-cells |

| NKG2A | Inhibitory | HLA-E | ITIM domains | Inhibits cytotoxicity against MHC-expressing cells |

| CD16 | Activating | IgG Fc region | CD3ζ, FcεRIγ | Mediates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathways governing NK cell activation and cytotoxicity:

Comparative Advantages: NK Cells vs. T Cells in Therapeutic Applications

Mechanism of Action Differences

The fundamental MoA differences between NK cells and T cells create distinct therapeutic profiles with complementary strengths. While T cells require antigen presentation via MHC and generate memory responses, NK cells operate through germline-encoded receptors that provide immediate reactivity without prior exposure [22]. This innate recognition capability enables NK cells to target a broader spectrum of abnormal cells, including those that have downregulated MHC to evade T-cell surveillance—a common immune escape mechanism in cancer [22]. Additionally, NK cells exhibit a lower risk of inducing cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity, severe side effects often associated with CAR-T therapies [22] [24].

Clinical evidence demonstrates that CAR-NK cell therapy causes fewer immune-related adverse events than CAR-T cell approaches. A Phase I/II trial of cord blood-derived CD19-targeted CAR-NK therapy reported no cases of cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, or graft-versus-host disease, despite achieving a 48.6% response rate and one-year overall survival of 68% in patients with CD19-positive B-cell malignancies [24]. This improved safety profile is attributed to differences in cytokine secretion patterns and activation kinetics between NK and T cells [22].

"Off-the-Shelf" Potential and Manufacturing Considerations

A transformative advantage of NK cell therapies is their capacity for allogeneic "off-the-shelf" applications without triggering significant graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [25] [24]. While most CAR-T cell therapies are autologous, requiring weeks for custom manufacturing for each patient, NK cells can be sourced from healthy donors, cord blood banks, or stem cell lines and manufactured in advance for immediate use [24]. This approach addresses critical limitations of current cell therapies, including manufacturing bottlenecks, high costs, and treatment delays that exclude patients with rapidly progressive diseases [25].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of CAR-NK vs. CAR-T Cell Therapies

| Parameter | CAR-NK Cells | CAR-T Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Allogeneic (healthy donors, iPSCs, cord blood) | Primarily autologous (patient's own cells) |

| Manufacturing Time | Pre-manufactured, immediate availability | 3-5 weeks custom manufacturing |

| MHC Restriction | No MHC restriction, target recognition is MHC-independent | MHC-dependent antigen presentation required |

| Toxicity Profile | Low incidence of CRS, neurotoxicity, and GvHD | Significant risk of CRS, neurotoxicity, and GvHD |

| Killing Mechanisms | CAR-dependent + natural cytotoxicity receptors | Primarily CAR-dependent |

| Persistence | Shorter persistence in vivo | Long-term persistence possible |

| Target Spectrum | Broad, can target heterogeneous tumors | Narrow, requires uniform antigen expression |

| Cost | Lower potential cost (off-the-shelf) | Higher cost (patient-specific manufacturing) |

Engineering advances are further enhancing the "off-the-shelf" potential of NK cell therapies. Recent research from MIT and Harvard Medical School has demonstrated that NK cells can be modified to evade host immune rejection by downregulating HLA class I proteins using siRNA, while simultaneously incorporating protective proteins like PD-L1 or single-chain HLA-E [26]. In murine models with humanized immune systems, these engineered CAR-NK cells persisted for at least three weeks and nearly eliminated lymphoma, while unmodified NK cells were rejected within two weeks [26].

Clinical Trial Landscape and Experimental Evidence

Hematological Malignancies: Efficacy and Safety Data

Clinical trials investigating NK cell therapies, particularly against hematological malignancies, are demonstrating compelling efficacy with favorable safety profiles. An interim analysis from the phase I SENTI-202-101 clinical trial presented at AACR 2025 reported complete remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated with SENTI-202, a logic-gated CAR-NK cell therapy [25]. Among seven evaluable patients, four achieved complete remission with no evidence of measurable residual disease, and all responses were ongoing with maximum follow-up exceeding eight months [25]. Notably, no dose-limiting toxicities were observed, and the maximum tolerated dose was not reached, supporting the favorable safety profile of NK cell approaches [25].

The innovative design of SENTI-202 incorporates logic-gating technology to enhance specificity. The CAR-NK cells recognize two different AML targets (CD33 and FLT3) to address tumor heterogeneity, while containing an inhibitory receptor that prevents killing of healthy cells co-expressing EMCN, a protein found on normal hematopoietic stem cells [25]. This sophisticated targeting strategy demonstrates how engineered NK cells can overcome fundamental challenges in cancer therapy that have limited more conventional approaches.

Solid Tumors: Challenges and Emerging Strategies

While NK cell therapies show promise in hematological malignancies, their application against solid tumors presents unique challenges. A comprehensive analysis of the global clinical landscape for NK cell therapies in solid tumors identified 141 relevant trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov as of December 2024 [27]. The geographical distribution shows China leading with 62 trials (44.0%), followed by the United States with 45 trials (31.9%), while no relevant trials were conducted in Africa or South America, highlighting significant global disparities in cell therapy research [27].

Most clinical investigations for solid tumors remain in early development phases, with Phase I trials constituting the largest proportion (39.7%), followed by Phase I/II trials (30.5%) [27]. No Phase III or IV clinical trials have been initiated, indicating the field is still establishing foundational safety and efficacy data [27]. Lung cancer is the most frequently targeted solid tumor (14.2% of trials), with a substantial portion of trials (29.1%) focusing on solid tumors generally rather than specific cancer types [27].

Table 3: Global Clinical Trial Landscape for NK Cell Therapies in Solid Tumors

| Parameter | Distribution | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical Distribution | China | 62 | 44.0% |

| United States | 45 | 31.9% | |

| Spain | 4 | 2.8% | |

| Other countries | 30 | 21.3% | |

| Trial Phase | Phase I | 56 | 39.7% |

| Phase I/II | 43 | 30.5% | |

| Phase II | 28 | 19.9% | |

| Not specified | 14 | 9.9% | |

| Tumor Types | Lung cancer | 20 | 14.2% |

| Breast cancer | 12 | 8.5% | |

| Colorectal cancer | 10 | 7.1% | |

| Ovarian cancer | 9 | 6.4% | |

| Glioblastoma | 8 | 5.7% | |

| Various/unspecified | 41 | 29.1% |

Major barriers to NK cell efficacy in solid tumors include the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), physical barriers formed by dense extracellular matrix, and tumor heterogeneity [27]. The TME contains various cell populations, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), that secrete factors suppressing NK cell function [22]. Strategies to overcome these limitations include engineering CAR-NK cells to target solid tumor antigens, armoring with cytokines to enhance persistence, and combining with checkpoint inhibitors to reverse NK cell exhaustion [24] [27].

Engineering Innovations and Experimental Approaches

Advanced Engineering Strategies

The engineering landscape for NK cells is rapidly evolving beyond first-generation CAR constructs to incorporate sophisticated control systems and enhanced functionality. Logic-gating approaches, such as those employed in the SENTI-202 therapy, represent a significant advancement in precision targeting [25]. These systems require recognition of multiple antigens before initiating cytotoxic responses, reducing off-target effects against healthy tissues that express only single targets. The incorporation of inhibitory receptors that recognize "self" markers provides an additional layer of selectivity, potentially expanding the therapeutic window for targeting antigens expressed at varying levels on both malignant and healthy cells.

Other innovative engineering strategies include cytokine armoring to enhance persistence and functionality. At MD Anderson Cancer Center, researchers are developing IL-21 engineered NK cells for glioblastoma treatment, with preclinical models demonstrating superior safety, metabolic fitness, and anti-tumor activity compared to IL-15 engineered counterparts [24]. Alternative approaches include engineering NK cells with T-cell receptors (TCRs) to recognize intracellular targets, significantly expanding the repertoire of targetable antigens [24]. Additionally, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived NK cells offer advantages in homogeneity, genetic engineering flexibility, and scalable manufacturing [27].

Experimental Protocols for NK Cell Engineering

A representative experimental protocol for generating engineered CAR-NK cells involves several critical stages. The following methodology synthesizes approaches from recent high-impact studies:

NK Cell Isolation and Activation:

- Source NK cells from peripheral blood, cord blood, or iPSCs using density gradient centrifugation

- Isolate pure NK cell populations using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with CD56 or CD3 depletion/CD56 positive selection

- Activate cells with IL-2 (100-200 IU/mL) + IL-15 (10-20 ng/mL) for 24-48 hours to enhance transduction efficiency

Genetic Modification:

- Employ lentiviral or retroviral transduction with CAR constructs, typically achieving 30-60% transduction efficiency

- Alternative approach: Use electroporation for mRNA-based transient CAR expression (higher safety profile)

- Advanced engineering: Incorporate siRNA to downregulate HLA class I proteins, preventing host immune rejection [26]

CAR Construct Design:

- Second-generation CARs typically include: extracellular scFv targeting domain, hinge region, transmembrane domain, and intracellular signaling domains (CD3ζ plus co-stimulatory domains such as 4-1BB or CD28)

- Incorporate suicide genes (iCasp9) or elimination tags for safety control

- Logic-gate constructs: Include multiple antigen recognition domains with AND/NOT logic capabilities [25]

Expansion and Quality Control:

- Expand engineered NK cells using feeder cells (e.g., K562-based artificial antigen-presenting cells) or cytokine-only methods

- Culture for 14-21 days to achieve clinical-scale cell numbers (1-5×10^9 cells)

- Validate CAR expression by flow cytometry, cytotoxic function against target cells, and cytokine production profile

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for generating engineered "off-the-shelf" CAR-NK cells:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for NK Cell Therapy Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | CD56 MicroBeads, CD3 Depletion Kits | NK cell purification from PBMCs | Positive/negative selection for pure NK populations |

| Cytokines | IL-2, IL-15, IL-21, IL-12, IL-18 | NK cell activation and expansion | Enhance cytotoxicity, persistence, and metabolic fitness |

| Activation Reagents | K562-based aAPCs, Fc-coated beads | Large-scale NK cell expansion | Provide co-stimulatory signals for proliferation |

| CAR Constructs | Lentiviral/retroviral vectors, mRNA | Genetic modification of NK cells | Introduce tumor-targeting specificity |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD56, CD16, NKG2D, NKp46 | Phenotypic characterization | Identify NK subsets and activation status |

| Functional Assays | Degranulation (CD107a), Cytotoxicity | Functional validation | Measure target cell killing capacity |

| Cell Lines | NK-92, NKL, K562, 721.221 | In vitro studies | Provide standardized models for experimentation |

NK cell therapies represent a transformative approach in the cell therapy landscape, distinguished by their unique innate immune mechanisms and compelling "off-the-shelf" potential. Their capacity for rapid, MHC-unrestricted target recognition, coupled with favorable safety profiles and reduced manufacturing constraints, positions them as powerful complements to established T-cell therapies. Current clinical evidence demonstrates particular promise in hematological malignancies, with ongoing engineering innovations addressing the challenges of solid tumors and therapeutic precision.

The future trajectory of NK cell therapy development will likely focus on enhancing persistence and functionality within suppressive tumor microenvironments, refining logic-gated control systems for improved safety profiles, and establishing scalable manufacturing platforms for widespread clinical accessibility. As the field advances toward later-stage clinical trials and potential regulatory approvals, NK cell therapies are poised to expand the armamentarium of cell-based immunotherapies, ultimately increasing treatment options for patients with diverse malignancies. Continued investigation into the fundamental biology of NK cells will undoubtedly reveal new opportunities for engineering refinement and therapeutic application across a broadening spectrum of diseases.

The therapeutic application of stem cells, particularly Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), is a cornerstone of modern regenerative medicine. For researchers and drug development professionals, a critical understanding of the two primary proposed mechanisms of action (MoA)—direct differentiation and paracrine signaling—is essential for designing effective therapies. Initially, the field was dominated by the paradigm of direct differentiation, where stem cells were thought to engraft and replace damaged tissues. However, emerging clinical and preclinical evidence now strongly suggests that the primary MoA is the secretion of bioactive molecules, a phenomenon known as paracrine signaling [28] [29]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these mechanisms, supported by experimental data and methodologies, to inform strategic decisions in cell therapy research.

Direct Differentiation: The Engraftment and Replacement Hypothesis

The direct differentiation mechanism posits that administered stem cells migrate to the site of injury, engraft into the host tissue, and subsequently differentiate into specific functional cell types to replace those that are damaged or lost.

Supporting Experimental Evidence and Protocols

Evidence for this mechanism often comes from in vitro differentiation assays and in vivo lineage tracing.

In Vitro Trilineage Differentiation: This is a foundational protocol per the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) criteria for defining MSCs [29]. The methodology involves culturing MSCs under specific conditions to induce differentiation.

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Culture MSCs in medium supplemented with dexamethasone, ascorbic acid, and β-glycerophosphate for 2-3 weeks. Differentiated osteoblasts are confirmed by staining for mineral deposits with Alizarin Red S [29].

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet cultures of MSCs are maintained in a medium containing TGF-β3 and dexamethasone for 3-4 weeks. Chondrogenesis is verified by staining for proteoglycans with Alizarin Blue or immunohistochemistry for collagen type II [29].

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Culture MSCs with dexamethasone, indomethacin, and insulin. Differentiated adipocytes are identified by the presence of lipid vacuoles stained with Oil Red O [29].

In Vivo Lineage Tracing: Advanced genetic fate-mapping in animal models is used to track the persistence and differentiation of transplanted donor cells. However, these studies frequently show low engraftment efficiency, with most donor cells being cleared within days to weeks [28].

Quantitative Data on Direct Differentiation

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings related to the direct differentiation mechanism:

Table 1: Experimental Data Supporting Direct Differentiation

| Evidence Type | Experimental Model | Key Finding | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Differentiation | Human MSCs | Capacity to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages (ISCT criteria). | [29] |

| In Vivo Engraftment | Murine Models | Low engraftment efficiency; donor cells are often transient. | [28] |

| Functional Improvement | Clinical Trials (e.g., Stroke) | Improvement in NIHSS, BI, and mRS scores observed over 6-12 months. | [30] |

Paracrine Signaling: The Bioactive Secretome as the Primary Driver

The paracrine signaling mechanism suggests that the therapeutic benefits of stem cells are mediated predominantly through their secretome—a complex mixture of growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs). These factors modulate the local microenvironment, reduce inflammation, promote angiogenesis, and activate endogenous repair pathways.

Molecular Mechanisms and Key Signaling Pathways

The paracrine effects are coordinated through several key signaling pathways that can be pharmacologically modulated to enhance therapeutic efficacy [31].

Figure 1: Key paracrine signaling pathways activated by the MSC secretome and their primary therapeutic effects.

Supporting Experimental Evidence and Protocols

- Secretome Analysis: The critical step is profiling the MSC-conditioned medium.

- Protocol: Serum-starve confluent MSCs and collect conditioned medium after 24-48 hours. Analyze the composition using proteomics (e.g., mass spectrometry for growth factors like VEGF, HGF), cytokine arrays, and techniques for characterizing extracellular vesicles (e.g., nanoparticle tracking analysis, electron microscopy) [32] [29].

- Functional In Vitro Assays:

- Angiogenesis Assay: Treat human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with MSC-conditioned medium. The formation of tube-like structures on a Matrigel substrate is quantified, demonstrating the pro-angiogenic effect of the secretome [32].

- Immune Modulation Assay: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and stimulate them with a mitogen like concanavalin A. Co-culture with MSCs or their conditioned medium, and measure T-cell proliferation via 3H-thymidine incorporation or CFSE staining, confirming immunomodulatory capacity [29].

- In Vivo Validation with Cell-Free Therapies: The therapeutic efficacy of the secretome alone can be tested.

- Protocol: In a rodent myocardial infarction model, administer MSC-derived exosomes or concentrated conditioned medium versus a control. Evaluate outcomes through histology (reduction in infarct size), echocardiography (improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction), and immunohistochemistry (increased capillary density) [32] [28].

Quantitative Data on Paracrine Signaling

The table below consolidates quantitative evidence highlighting the significance of the paracrine mechanism.

Table 2: Experimental Data Supporting Paracrine Signaling

| Evidence Type | Experimental Model | Key Finding | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Survival Post-Transplant | Coronary MSC Delivery | MSC survival rate < 5-10% within 72 hours, yet functional improvement is observed. | [32] [28] |

| Exosome/Secretome Efficacy | Rodent Myocardial Infarction | MSC-derived exosomes improve cardiac function, reduce fibrosis, and enhance vessel density. | [32] [28] |

| Clinical Safety & Efficacy | Stroke Clinical Trials | Significant functional recovery (NIHSS, BI) without correlation to long-term engraftment. | [30] |

| Specific Molecule Action | In Vitro/In Vivo Models | MSC exosomes carry miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a) that regulate apoptosis and fibrosis. | [32] [29] |

Direct Comparison: Paracrine Signaling vs. Direct Differentiation

A head-to-head comparison of these mechanisms reveals distinct characteristics, with the paracrine effect offering several translational advantages.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Primary Therapeutic Mechanisms

| Feature | Direct Differentiation | Paracrine Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| Primary MoA | Cell replacement and structural integration. | Modification of the host microenvironment via secreted factors. |

| Therapeutic Speed | Slow (requires engraftment and maturation). | Relatively fast (immediate bioactivity of molecules). |

| Engraftment Requirement | Absolutely critical; a major technical hurdle. | Not required; effects are elicited transiently. |

| Key Evidence | In vitro trilineage differentiation; early histology. | Functional recovery despite low cell survival; efficacy of conditioned medium/exosomes. |

| Major Challenges | Extremely low efficiency; poor cell survival; risk of ectopic tissue formation. | Standardizing the secretome; manufacturing reproducible cell-free products. |

| Clinical Translation | Challenging due to engraftment barriers. | Highly promising; facilitates "off-the-shelf" and cell-free products. |

The following diagram synthesizes the experimental workflow for elucidating the dominant mechanism of action in a therapeutic context.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for determining the primary mechanism of action (MoA).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Advancing research in this field requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for studying stem cell mechanisms.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Stem Cell MoA

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function and Application | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits | Defined media supplements for in vitro induction of osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages. | Validating multipotency of MSC batches per ISCT criteria [29]. |

| Cell Tracking Dyes (e.g., CFSE, PKH26) | Fluorescent labels for tracking the migration, persistence, and fate of administered cells in vivo. | Quantifying MSC engraftment and distribution in animal disease models [28]. |

| Exosome Isolation Kits | Polymer-based precipitation or size-exclusion chromatography for purifying extracellular vesicles from conditioned medium. | Isposing MSC-derived exosomes for functional cell-free therapy studies [32] [29]. |

| Cytokine & Growth Factor Arrays | Multiplexed immunoassays for simultaneous quantification of dozens of secreted proteins in conditioned medium. | Profiling the MSC secretome under different priming conditions (e.g., hypoxia) [29]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene-editing tool for knocking out (KO) specific genes in MSCs to study their functional role in the secretome. | Creating TGF-β1 KO MSCs to test the pathway's necessity for immunomodulation [31]. |

| SMAD & β-catenin Inhibitors | Small molecule inhibitors (e.g., SB431542 for TGF-β, IWR-1 for Wnt) to block specific signaling pathways. | Pharmacologically dissecting the contribution of pathways to MSC therapeutic effects [31]. |

The accumulated evidence from both preclinical models and clinical trials strongly positions paracrine signaling as the dominant mechanism of action for most MSC-based therapies. The observed functional recoveries in conditions like stroke and myocardial infarction, despite minimal long-term engraftment, are difficult to attribute to direct differentiation [30] [32] [28]. This paradigm shift has significant implications for drug development, redirecting focus towards optimizing the secretome, developing potent cell-free therapeutics, and utilizing pharmacological strategies to enhance endogenous stem cell function [31]. Future research will concentrate on standardizing secretome-based products, engineering MSCs to overexpress beneficial factors, and leveraging pharmacological modulators to precisely control stem cell fate and function, thereby ushering in a new era of safe and effective regenerative medicines.

For researchers and drug development professionals in the cell and gene therapy space, demonstrating a product's mechanism of action (MoA) and quantitatively measuring its biological activity through potency assays represents one of the most significant development challenges. Regulatory agencies worldwide recognize potency as a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) that must be measured for each product lot to ensure the therapy will achieve its intended clinical effect [2] [33]. The fundamental relationship between these concepts can be visualized as a continuous chain: a therapy's MoA defines its functional attributes (potency), which must be measurable through biological assays, and successful execution of this mechanism in patients manifests as clinical efficacy [1].

The development path requires connecting laboratory measurements to clinical outcomes. As noted in analyses of FDA-approved cell therapy products (CTPs), "potency is laboratory whereas efficacy is clinical; and the two are tied together by the MOA" [1]. This perspective examines this critical link, exploring how MoA understanding directly shapes potency assay development, the challenges in correlating these assays with clinical outcomes, and emerging solutions for researchers developing advanced therapies.

MoA as the Foundation for Potency Assessment

Defining the Framework

Clear conceptual distinctions between mechanism of action, potency, and efficacy are essential for effective assay development and regulatory communication. According to recent frameworks published in the Journal of Translational Medicine, these key terms can be defined as follows [1]:

- Mechanism of Action (MoA): The specific process, often pharmacologic, through which a product produces its intended effect

- Potency: The attribute of a product that enables it to achieve its intended mechanism of action

- Potency Test: A test that measures the attribute of a product that enables it to achieve its intended mechanism of action

- Efficacy: The ability of the product to have the desired effect in patients

- Efficacy Endpoint: Attributes related to how a patient feels, functions, or survives

This framework highlights that potency and efficacy, while related, exist in different domains - with potency being a product attribute measurable in the laboratory, and efficacy being the clinical manifestation of that attribute in patients.

Current Landscape of Approved Therapies

Analysis of the 27 FDA-approved cell therapy products (as of February 2024) reveals significant challenges in connecting MoA, potency, and clinical efficacy. For many products, including Provenge, Gintuit, MACI, and Amtagvi, regulatory documentation indicates that the MoA is not fully known [1]. For other therapies like Kymriah, the first approved CAR-T cell therapy, regulators have noted difficulty correlating potency test results with efficacy, despite the product demonstrating clinical benefit [1].

Table 1: MoA and Potency Assessment in Approved Cell Therapies

| Product Name | Therapy Type | Indication | Reported MoA Understanding | Potency Test Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kymriah | CAR-T Cell | Leukemia | Targeted cell destruction | Difficult to correlate IFN-γ production with efficacy |

| Provenge | Autologous Cellular | Prostate Cancer | Not known | Based on CD54 upregulation |

| MACI | Tissue-Engineered | Cartilage Defects | Not known | Cell viability and morphology |

| Gintuit | Allogeneic Cellular | Mucosal Tissue | Not known | Cell viability and identity |

| Amtagvi | Autologous T Cell | Melanoma | Not known | T cell activation and phenotype |

| Rethymic | Allogeneic Cellular | Congenital Athymia | Proposed | T cell population composition |

| Lantidra | Allogeneic Islet Cell | Type 1 Diabetes | Believed | Insulin secretion and mitochondrial function |

MoA-Based Potency Assay Development: Methodologies and Case Studies

CAR T-Cell Therapy: Multi-Functional Assessment

For CAR T-cell therapies, the MoA involves a multi-step process beginning with antigen recognition, followed by T-cell activation, proliferation, cytokine release, and ultimately target cell destruction [11]. This complex mechanism necessitates a matrix of potency assays that capture these different functional dimensions:

- Immediate Effector Function: Measured through cytotoxicity assays, cytokine release (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2), and degranulation markers (e.g., LAMP1 expression)

- Expansion Capacity: Assessed through cell proliferation and viability measurements

- Persistence Potential: Evaluated through phenotypic characterization, in vivo tracking, and CAR transgene expression monitoring [11]

The potency of FDA-approved CAR T-cell products is primarily assessed by measuring IFN-γ release in response to target cells, alongside other factors including cell viability and CAR expression levels [11]. However, recent advances in multi-omics approaches are revealing additional product characteristics that correlate with clinical function, suggesting future potency assays may need greater sophistication.

Table 2: CAR T-Cell Potency Assay Matrix Based on MoA Components

| MoA Component | Assay Type | Measured Parameters | Technology Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen Recognition | Binding Assay | CAR surface expression, binding affinity | Flow cytometry, SPR |

| T-cell Activation | Functional Assay | Activation markers, early signaling | CD69/CD137 detection, phospho-flow |

| Effector Function | Co-culture Assay | Cytotoxicity, cytokine secretion | Incucyte, ELISA, Luminex |

| Expansion Capacity | Proliferation Assay | Cell division, population doubling | CFSE dilution, cell counting |

| Persistence Potential | Phenotypic Assay | Memory markers, exhaustion markers | scRNA-seq, flow cytometry |

CD34+ Cell Therapy: Pro-angiogenic Secretion

For ProtheraCytes (expanded autologous CD34+ cells) used in myocardial regeneration, the MoA involves revascularizing damaged myocardial tissue through secretion of pro-angiogenic factors, particularly vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [34]. This understanding directly informed the development of a potency assay based on VEGF quantification during CD34+ cell expansion.

Experimental Protocol: VEGF Potency Assay Validation

- Cell Culture: CD34+ cells from AMI patients expanded for 9 days in StemFeed medium

- Sample Collection: Supernatants collected after expansion period

- Analysis Platform: Automated ELLA immunoassay system with VEGF cartridge

- Validation Parameters: Specificity, linearity (20-2800 pg/mL), precision (CV ≤10% repeatability, ≤20% intermediate precision), accuracy (85-105% recovery) [34]

The validated assay demonstrated significant VEGF secretion (596.2 ± 242.3 pg/mL in AMI patients, comparable to healthy donors) while negative controls (culture medium alone) showed minimal VEGF (2.8 ± 0.2 pg/mL) [34]. This MoA-based approach provided a quantitative, reproducible potency measure that regulatory agencies deemed acceptable for clinical batch release.

Gene Therapy: Functional Transgene Assessment

For gene therapies like voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna), an AAV2 vector expressing RPE65 for retinal disease, the MoA involves successful transduction of target cells and functional transgene expression producing biologically active protein [35]. This informed development of a cell-based relative potency assay measuring both transduction efficiency and enzymatic activity.

Experimental Protocol: Luxturna Potency Assay

- Cell Line: HEK293 cells

- Transduction: AAV2-hRPE65v2 vector

- Functional Readout: RPE65 enzymatic conversion of all-trans-retinol to 11-cis-retinol

- Quantification Method: Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Validation Range: 50%-150% of reference standard potency [35]

This approach successfully supported regulatory approval by demonstrating lot-to-lot consistency and biological activity aligned with the therapy's MoA, representing the first validated in vitro cell-based relative potency assay for an AAV vector [35].

Advanced Technologies and Methodologies

Multi-Omics Approaches in Potency Assessment

Advanced profiling technologies are expanding our understanding of CAR T-cell products at multiple molecular levels, revealing new potential potency correlates:

- Genomic Profiles: Vector copy number (VCN), integration sites, TCR repertoire diversity

- Epigenomic Profiles: DNA methylation patterns, chromatin accessibility associated with persistence

- Transcriptomic Profiles: Gene expression signatures, T-cell differentiation states

- Proteomic Profiles: Protein expression, activation markers, cytokine secretion

- Metabolomic Profiles: Metabolic fitness, energy pathways [11]

These approaches are particularly valuable for identifying correlates of clinical response. For example, DNA methylation analysis of 114 CD19 CAR T-cell products identified 18 distinct epigenetic loci associated with complete response, event-free survival, and overall survival [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MoA-Based Potency Assays

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Potency Assessment | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Immunoassay Systems (e.g., ELLA) | Quantitative protein detection | VEGF measurement in CD34+ cell supernatants [34] |

| Custom Cell Mimics (e.g., TruCytes) | Standardized target cells for functional assays | CAR T-cell activation and cytokine response [2] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Transcriptional profiling at single-cell resolution | T-cell differentiation states, exhaustion signatures [11] |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute quantification of vector copy number | CAR transgene quantification for lot-release [11] |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Quantitative analysis of enzymatic products | RPE65 enzymatic activity in gene therapy [35] |

| Flow Cytometry Panels | Multiparameter cell surface and intracellular staining | Immunophenotyping, activation markers, memory subsets |

Visualizing the MoA-Potency-Efficacy Relationship

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and experimental workflow connecting MoA understanding to potency assay development and clinical efficacy assessment:

MoA to Efficacy Assessment Pathway - This diagram maps the logical relationships from mechanism of action understanding through potency measurement to clinical efficacy evaluation.

The experimental workflow for developing and validating MoA-based potency assays follows a systematic process:

Potency Assay Development Workflow - This chart outlines the staged process from initial MoA research through to validated assay implementation for product lot release.

Challenges and Future Directions

Correlation with Clinical Outcomes

A fundamental challenge in potency assay development remains demonstrating correlation between in vitro potency measurements and clinical efficacy. Analysis of the Kymriah clinical program revealed that while IFNγ production (the potency measure) showed some correlation with remission, there was significant overlap between responders and non-responders [1]. FDA documentation noted that "IFN-γ production varied greatly from lot-to-lot, making it difficult to correlate IFN-γ production in vitro with tisagenlecleucel safety or efficacy" [1].

This challenge is compounded when MoA is incompletely understood. As noted in analyses of approved products, "for many of the 27 US FDA-approved CTPs, the relationships between the potency tests and proposed MOAs are unclear" [1]. This reality necessitates a pragmatic approach where products may receive regulatory approval based on demonstrated clinical efficacy and acceptable risk-benefit profile, even when the potency test doesn't fully correlate with efficacy endpoint test results [1].

Emerging Solutions and Strategies

Several strategies are emerging to address these challenges:

- Early Potency Planning: Initiating potency assay development during preclinical stages helps guide process decisions and prevent late-stage delays [2] [36]

- Assay Matrices: For complex therapies with multifaceted MoAs, a matrix of complementary potency assays may better capture biological activity than any single assay [11]