Demonstrating Comparability for Biological Products: A 2025 Guide to Regulatory Strategy, Analytical Methods, and Lifecycle Management

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on demonstrating comparability for biological products.

Demonstrating Comparability for Biological Products: A 2025 Guide to Regulatory Strategy, Analytical Methods, and Lifecycle Management

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on demonstrating comparability for biological products. Covering foundational principles from ICH Q5E to the latest 2025 regulatory updates from the FDA and EMA, it details a risk-based methodology for analytical, non-clinical, and clinical assessments. The content explores troubleshooting for expedited programs and complex changes, alongside a comparative analysis of biosimilar pathways and global regulatory convergence. By synthesizing current guidelines and expert consensus, this resource aims to equip scientists with the strategies needed to efficiently manage manufacturing changes and biosimilar development, accelerating patient access to vital therapies.

The Foundations of Comparability: From ICH Q5E Principles to the 2025 Regulatory Paradigm Shift

The development and manufacturing of biotechnological/biological products are inherently dynamic, often necessitating process changes throughout the product lifecycle. ICH Q5E provides the foundational framework for assessing the comparability of a product before and after such manufacturing changes, introducing the crucial concept of "highly similar" as the standard for successful demonstration. This whitepaper delves into the technical and regulatory nuances of this standard, explaining that it does not imply identity but rather demands a comprehensive analytical and scientific evaluation to ensure that differences have no adverse impact on the product's quality, safety, or efficacy. Framed within the broader context of demonstrating comparability for biological products research, this guide provides drug development professionals with a detailed examination of the regulatory expectations, a strategic framework for risk-based study design, and specific methodological protocols for key analytical experiments. By synthesizing the principles of ICH Q5E with contemporary industry practices, this document aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design robust, defensible comparability exercises that facilitate continuous process improvement while ensuring patient safety and regulatory compliance.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q5E guideline, titled "Comparability of Biotechnological/Biological Products Subject to Changes in Their Manufacturing Process," is the definitive regulatory document governing how manufacturers should evaluate changes to the manufacturing process of biological products [1] [2]. Its primary objective is to assist in the collection of relevant technical information that serves as evidence that a manufacturing process change will not adversely impact the quality, safety, and efficacy of the drug product [3]. The guideline emphasizes that the focus of the assessment should be primarily on quality aspects, and it does not prescribe a one-size-fits-all analytical, nonclinical, or clinical strategy [2].

Central to the ICH Q5E philosophy is the concept of "highly similar." This is a critical distinction from "identical," acknowledging the inherent complexity and natural variability of biological products. A biotechnological product is considered "highly similar" to its pre-change counterpart when the observed differences in quality attributes are thoroughly evaluated and scientifically justified as having no adverse impact on safety or efficacy [4]. This means that the product's safety, identification, purity, and activity should be highly similar and fully predictable based on existing knowledge [5]. The goal of the comparability exercise is therefore not to prove that the two products are exactly the same, but to ascertain that they are sufficiently comparable to ensure that the existing data on safety and efficacy remains valid for the post-change product [6] [4]. When a thorough analytical comparison can robustly demonstrate this "highly similar" state and link it to the clinical experience, additional non-clinical or clinical studies may be unnecessary [7].

The Scientific and Regulatory Foundation of "Highly Similar"

The Role of Product and Process Understanding

Demonstrating that a product is "highly similar" after a manufacturing change is fundamentally predicated on a deep and comprehensive understanding of the product and its manufacturing process. Biotechnological products are highly complex and are defined by their manufacturing process, a concept often summarized as "the product is the process" [6]. This complexity means that any process change has the potential to affect the product. A well-designed comparability exercise should therefore be capable of detecting discrete differences in selected quality attributes. Regulators expect that some differences will be revealed through modern, sensitive analytical techniques; the key scientific question is not whether any difference exists, but whether the observed differences are meaningful and could negatively impact safety or efficacy [6].

The foundation for this assessment is a well-defined list of Product Quality Attributes (PQAs), which are physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties or characteristics that should be within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality [6]. Among these, Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) are those PQAs that have a direct link to safety and efficacy. A robust risk-management process, as outlined in ICH Q9, is used to determine the criticality of each attribute [6] [4]. This product knowledge, accumulated throughout development, is essential for designing a focused and effective comparability study, as it allows the development team to predict which attributes are most likely to be affected by a specific process change.

The Hierarchy of Evidence and Regulatory Flexibility

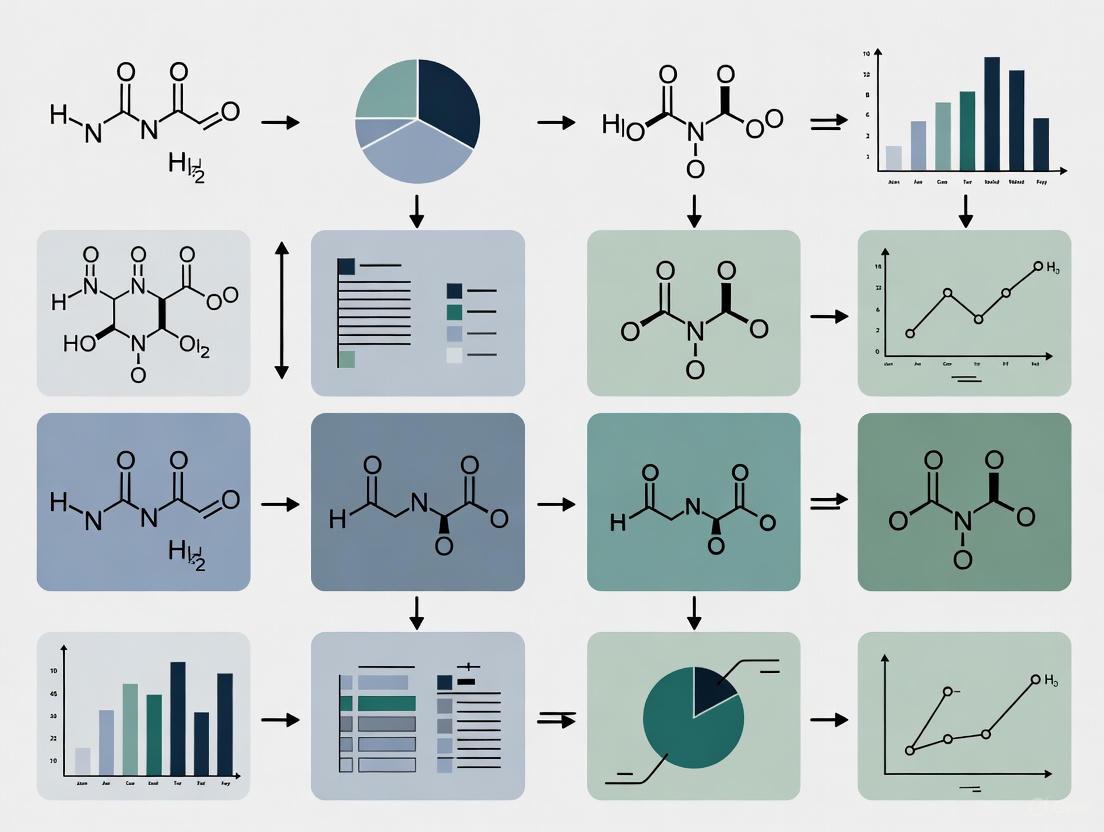

ICH Q5E establishes a hierarchical approach to demonstrating comparability, with analytical studies forming the cornerstone of the assessment [4]. The guideline envisions a stepwise progression of evidence gathering, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: The hierarchical, stepwise approach to demonstrating comparability, starting with analytical studies, as endorsed by ICH Q5E.

As shown, a comprehensive analytical comparability exercise is always the first and most critical step. If this analytical demonstration is successful in proving the products are "highly similar," then the comparability exercise can be considered complete without further non-clinical or clinical studies [7] [4]. However, if uncertainty remains after the analytical comparison, or if a difference with potential clinical impact is identified, the manufacturer may need to progress to non-clinical or clinical bridging studies to resolve the uncertainty and establish a link to the existing safety and efficacy data [6] [5]. The level of evidence required is also phase-appropriate; the extent of the comparability exercise should align with the stage of product development, with more comprehensive data expected for products in or near the marketing application stage compared to those in early clinical development [4].

Designing a Risk-Based Comparability Study

The Comparability Protocol: A Prospectively Written Plan

A cornerstone of a successful comparability exercise is the Comparability Protocol (CP), known in the EU as a Post-Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP) [7]. This is a comprehensive, prospectively written plan that outlines how the effect of a proposed change will be assessed [7]. Drafting the protocol should be initiated approximately six months before the manufacture of the post-change batch(es) and must be finalized before testing begins [6]. Submitting a CP for regulatory feedback prior to execution can de-risk the entire process, as it ensures alignment with regulatory authorities on the study design, analytical methods, and acceptance criteria. A key advantage is that meeting all predefined criteria in an approved protocol can allow for faster implementation of the change post-approval [7] [4].

A well-structured Comparability Protocol typically includes the following elements [6]:

- A detailed description and rationale for the process change(s).

- A risk-based impact assessment identifying potentially affected Product Quality Attributes (PQAs).

- A detailed analytical testing plan, including specified methods and sample types.

- Predefined acceptance criteria for the comparability study.

- A plan for stability studies, if required.

- A description of all available supportive historical data.

Risk Assessment and Impact Analysis

A critical early step in designing the study is to conduct a systematic risk assessment to identify which product quality attributes are most likely to be impacted by the specific manufacturing change. This involves a cross-functional team with representatives from analytical, process development, non-clinical, and regulatory affairs [6]. The team uses a structured template to link each process change to potentially affected PQAs, providing a scientific rationale for the potential impact.

Table 1: Risk Assessment Template for Linking Process Changes to Quality Attributes

| Process Change | Potentially Affected PQA | Rationale for Potential Impact | Recommended Analytical Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream Scale-Up | Glycosylation Profile | Alterations in cell culture conditions (shear stress, nutrient gradients) can affect glycosylation. | Oligosaccharide profiling (HPLC/UPLC) |

| Purification Resin Change | Charge Variants | Differences in ligand chemistry and separation mechanism may selectively remove certain charge species. | cIEF or CEX-HPLC |

| Cell Line Change | Primary Structure | A new clone may have different sequence variants or post-translational modification tendencies. | Peptide Mapping (LC-MS) |

| Drug Product Formulation Change | Higher-Order Structure & Aggregation | Changes in excipients or pH can destabilize the protein structure. | SEC-HPLC, DSC, CD Spectroscopy |

This risk assessment directly informs the scope and depth of the analytical testing plan, ensuring that resources are focused on monitoring the attributes that matter most for the specific change, thereby making the study both efficient and scientifically defensible [6] [4].

Batch Selection and Study Design

The number of batches selected for a comparability study depends on the product's development stage and the magnitude of the change. For major changes to marketed products, ≥3 batches of commercial-scale post-change material are generally recommended [5]. These are compared against historical data from multiple pre-change batches. An optimized study design leverages routine lot release and stability testing data generated for the post-change batches and compares them statistically to the historical data of all pre-change batches, rather than retesting a limited number of pre-change batches side-by-side [7]. This approach compares the post-change product against the manufacturer's entire experience with the pre-change process, providing a more robust assessment.

The following workflow outlines the key stages of a comparability exercise, from initial preparation to final reporting.

Diagram 2: The key stages of a comparability exercise, from foundational preparation through to final reporting.

Quantitative Standards and Analytical Methodologies

Defining Acceptance Criteria

A fundamental principle of ICH Q5E is the establishment of prospective acceptance criteria [6]. These criteria, defined before testing the post-change batches, are the objective standards against which comparability will be judged. It is important to note that these acceptance criteria are not necessarily the same as the routine quality standards for batch release. They should be set based on historical data from the pre-change process, taking into account the variability of the analytical methods and the observed range of the quality attributes [7] [5]. The criteria can be quantitative (e.g., a statistical range for a potency assay) or qualitative (e.g., comparable peak shapes in a chromatogram) [5].

Table 2: Examples of Acceptance Criteria for Common Analytical Tests

| Test Type | Specific Analysis | Example Acceptance Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Routine Release | SEC-HPLC for Aggregates | Meets release criteria; percentage of main peak (monomer) within a statistical range (e.g., ETTI) based on historical data; comparable elution profiles. |

| Peptide Map | Meets release criteria; comparable peak shapes based on retention time and relative intensity; no new or lost peaks. | |

| Cell-Based Potency Assay | Meets release criteria; relative potency within a predefined statistical acceptance range based on historical data. | |

| Extended Characterization | Intact Mass (LC-MS) | Molecular weight within the instrument's accuracy range; same species detected. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) | No significant qualitative differences in the spectra; quantitative analysis shows comparable conformational ratios. | |

| Stability | Real-time Stability | Degradation rates for key attributes (e.g., potency, purity) are equivalent to or slower than the historical average of pre-change batches. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Analytical Techniques for Demonstrating "Highly Similar"

A multi-tiered analytical strategy is employed, leveraging methods from routine release, extended characterization, and stability testing. The following table details key reagent solutions and analytical methodologies essential for a comprehensive comparability study.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Analytical Methods for Comparability

| Analytical Category | Technique / Reagent | Primary Function in Comparability |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Structure | Peptide Mapping (LC-MS) with Trypsin | Confirms amino acid sequence and identifies post-translational modifications (e.g., oxidations, deamidations) by comparing peptide fingerprints. |

| Intact and Reduced Mass Spectrometry | Verifies correct molecular weight and detects mass variants. | |

| Higher-Order Structure | Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy | Probes secondary (far-UV) and tertiary (near-UV) structure to ensure conformational integrity. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measures thermal stability and unfolding profiles, indicating overall structural robustness. | |

| Charge Variants | capillary Isoelectric Focusing (cIEF) / Cation-Exchange Chromatography (CEX-HPLC) | Separates and quantifies charge variants (e.g., acidic and basic species) which can impact activity and stability. |

| Purity & Impurities | Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC-HPLC) | Quantifies soluble aggregates and fragments. |

| CE-SDS (reduced and non-reduced) | Provides high-resolution separation and quantification of size variants, including fragments and non-glycosylated heavy chain. | |

| Glycosylation | Oligosaccharide Profiling (HPLC/UPLC) | Characterizes the glycan distribution, a CQA for many biologics that can affect efficacy (e.g., ADCC) and safety. |

| Functionality | Cell-Based Bioassays | Measures the biological potency of the product by assessing its mechanism-of-action (MoA)-relevant activity. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Quantifies binding affinity (KD) to relevant targets and receptors. | |

| Process-Related Impurities | ELISA Kits (HCP, Protein A) | Quantifies residual host cell proteins and leached Protein A from chromatography resins. |

The strategy should prioritize quantitative methods and employ orthogonal methods (multiple methods that measure the same attribute through different physical principles) for quality attributes that are closely linked to function, such as higher-order structure and glycosylation [6]. The methods must be fit-for-purpose, meaning they have been shown to be capable of reliably detecting differences that might be expected from the specific manufacturing change [7].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analytical Methods

Protocol for Peptide Mapping with LC-MS for Primary Structure Analysis

Objective: To confirm the amino acid sequence and identify post-translational modifications (PTMs) in the post-change product compared to the pre-change reference.

Methodology:

- Denaturation, Reduction, and Alkylation: Dilute the protein sample to a target concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in a denaturing buffer (e.g., 6 M Guanidine HCl). Reduce disulfide bonds using dithiothreitol (DTT) or tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Alkylate the free thiols with iodoacetamide or iodoacetic acid to prevent reformation.

- Digestion: Desalt the protein using a buffer exchange cartridge or dialysis into a digestion-compatible buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). Add a proteolytic enzyme, typically trypsin, at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:20 to 1:50 (w/w). Incubate at 37°C for 4-18 hours.

- LC-MS Analysis: Separate the resulting peptides using reversed-phase U/HPLC on a C18 column with a water-acetonitrile gradient (0.1% Formic Acid as modifier). Couple the HPLC system to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap).

- Data Processing and Comparison: Use software to deconvolute the MS data and identify peptides based on their measured mass and MS/MS fragmentation patterns. Compare the resulting peptide maps of the pre- and post-change samples. Key comparability endpoints include:

- Retention Time and Peak Area: The chromatographic profile should be highly similar.

- Sequence Coverage: Should be ≥95% and identical between samples.

- PTM Identification and Quantification: The type and level of PTMs (e.g., oxidation of Met, deamidation of Asn/Gln) should be within the historical range or predefined acceptance criteria.

Protocol for Monitoring Higher-Order Structure by Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

Objective: To assess the secondary and tertiary structure of the protein and ensure no significant conformational changes have occurred due to the process change.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze or dilute the protein into a CD-compatible buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer). Avoid buffers with high absorbance in the far-UV region (e.g., citrate, Tris). Determine the exact protein concentration using a UV spectrophotometer (A280 measurement).

- Far-UV CD (Secondary Structure): Load the sample into a quartz cuvette with a short path length (e.g., 0.1 cm). Record the spectrum from 180-260 nm. Perform multiple scans and average them to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Subtract the buffer blank spectrum.

- Near-UV CD (Tertiary Structure): Use a higher protein concentration and a cuvette with a longer path length (e.g., 1 cm). Record the spectrum from 250-350 nm.

- Data Analysis and Comparability Assessment: Visually overlay the spectra of the pre- and post-change samples. For a more quantitative assessment, use algorithms to deconvolute the far-UV spectrum and estimate the percentages of α-helix, β-sheet, and random coil. The conclusion of "highly similar" is supported by:

- No significant shifts in the peak positions (wavelength) for both far- and near-UV spectra.

- Comparable mean residue ellipticity values at key peaks and troughs.

- A comparable calculated secondary structure composition.

Protocol for Stability Study Comparison

Objective: To demonstrate that the degradation pathways and kinetics of the post-change product are comparable to the pre-change product.

Methodology:

- Study Design: Place a minimum of three post-change batches and, if available for side-by-side testing, three pre-change batches on stability under recommended storage conditions (e.g., 5°C ± 3°C) and accelerated conditions (e.g., 25°C/60%RH). For supportive data, forced degradation studies (e.g., exposure to elevated temperature, light, oxidants) can be performed.

- Testing Time Points: Test at initial (T=0), 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months for real-time studies. Accelerated studies may have more frequent time points (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 6 months).

- Test Attributes: Monitor CQAs that are known to be stability-indicating, such as:

- Purity: SEC-HPLC (aggregates), CE-SDS (fragmentation), CEX/cIEF (charge variants).

- Potency: Cell-based bioassay.

- Activity: Binding affinity assays.

- Data Evaluation: Plot the degradation trends for each attribute over time. Statistically compare the degradation rates (slopes) of the post-change batches to the historical data from pre-change batches. The products are considered comparable in stability if:

- The degradation pathways are the same (no new degradation products appear).

- The degradation rates for key attributes are statistically equivalent to or slower than those of the pre-change product.

The "highly similar" standard articulated in ICH Q5E represents a pragmatic and scientifically rigorous framework for managing the inevitable evolution of biological manufacturing processes. It acknowledges the complexity of these products while demanding a level of evidence sufficient to ensure that process changes do not adversely affect patient safety or product efficacy. Successfully navigating this standard requires more than just routine testing; it demands a deep, proactive product and process understanding, a risk-based strategy for study design, and the skillful application of a broad panel of sophisticated analytical techniques. By embracing the principles outlined in this whitepaper—developing a comprehensive comparability protocol, conducting a systematic risk assessment, setting scientifically justified acceptance criteria, and employing fit-for-purpose analytical methods—drug development professionals can build robust, defensible comparability packages. This approach not only fulfills regulatory expectations but also fosters a culture of continuous improvement, ultimately enabling the delivery of high-quality, innovative biological therapies to patients in an efficient and reliable manner.

The 1996 FDA Guidance, "Demonstration of Comparability of Human Biological Products, Including Therapeutic Biotechnology-derived Products," established the foundational principle that biological products could be scientifically evaluated after manufacturing changes without necessarily repeating clinical efficacy studies [8]. This document represented a significant shift in regulatory philosophy, acknowledging that as characterization methods improved, biological products could be increasingly defined by their specific attributes rather than solely by their manufacturing process. The guidance provided a structured framework for demonstrating that pre-change and post-change products remained comparable in safety, identity, purity, and potency through rigorous analytical, functional, and sometimes preclinical testing [8]. This evolution from a purely process-based definition to an attribute-based understanding of biological products has enabled manufacturers to implement important improvements in product quality, yield, and manufacturing efficiency while maintaining regulatory compliance.

Over the past three decades, this conceptual framework has evolved substantially through international harmonization and adaptation to novel therapeutic modalities. The comparability concept has expanded from addressing relatively straightforward manufacturing changes to encompassing complex scenarios including the demonstration of biosimilarity and the evaluation of innovative platform technologies for personalized therapies. This article examines the trajectory of regulatory thinking from the seminal 1996 guidance through the recent updates and novel pathways announced in 2025, providing researchers and drug development professionals with both historical context and practical methodologies for navigating the current regulatory landscape for biological products.

The 1996 Guidance: A Foundational Framework

Core Principles and Regulatory Context

Issued in April 1996, the FDA's guidance on comparability represented a pivotal moment in the regulation of biological products. Historically, these products were regarded as complex mixtures that were difficult to characterize as individual entities, leading to a regulatory framework where the manufacturing process itself defined the product [8]. This perspective was reflected in the establishment license application (ELA) requirement for biologics, which acknowledged that changes in manufacturing could fundamentally alter the product itself. The 1996 guidance acknowledged that scientific advancements in production methods, process controls, and characterization techniques had evolved sufficiently to allow for a more nuanced approach [8]. It explicitly stated that manufacturers could implement manufacturing changes without additional clinical studies if they could demonstrate "product comparability" between the pre-change and post-change product through rigorous analytical and functional testing.

The guidance established that FDA would determine comparability based on whether manufacturing changes affected the safety, identity, purity, or potency of the biological product [8]. This represented a significant regulatory flexibility initiative, allowing manufacturers to bring improved products to market more efficiently while maintaining appropriate safeguards for product quality. The document emphasized that this approach applied to both products regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and therapeutic biotechnology-derived products regulated by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) [8]. Importantly, the guidance clarified that it represented the FDA's current thinking on demonstration of product comparability but did not set forth binding requirements, allowing for alternative approaches with prior FDA discussion.

Structured Approach to Comparability Testing

The 1996 guidance outlined a comprehensive, scientifically-grounded approach to comparability assessment that emphasized knowledge of the manufacturing process as integral to designing an appropriate testing program [8]. The recommended testing strategy typically progressed from analytical characterization to biological assays, and when necessary, to preclinical and clinical evaluation, though the approach was not strictly hierarchical. The guidance recognized that different tests often provided complementary information, and that understanding the extent of manufacturing changes and their stage of implementation was crucial for designing an appropriate assessment program [8].

Manufacturers were advised to provide extensive side-by-side analyses of the pre-change and post-change products, using well-characterized reference standards when available [8]. The testing strategy incorporated both routine release assays and additional tests specifically designed to evaluate the impact of the particular manufacturing change. The guidance specifically highlighted several categories of critical assessment methods:

- Analytical Testing: Comprehensive chemical and physical characterization to identify similarities and differences between products [8]

- Bioassays: In vitro or in vivo assessments of biological activity that reflect the product's mechanism of action [8]

- Preclinical Animal Studies: Evaluations of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and potential toxicity in relevant animal models [8]

- Clinical Studies: Assessments of human pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and efficacy when needed [8]

The guidance emphasized that the most important consideration was whether any observed differences would translate into significant changes in clinical safety or efficacy, with the overall goal of determining whether additional clinical studies were necessary [8].

The Evolution to ICH Q5E: International Harmonization

Refinement of Scientific Principles

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q5E guideline, issued in June 2005, represented the next major evolution in comparability thinking by providing an internationally harmonized framework for assessing comparability of biotechnological/biological products after manufacturing changes [2]. Building upon the foundation established in the 1996 FDA guidance, Q5E more explicitly articulated the scientific principles underlying comparability assessment and provided greater detail on the technical considerations for demonstrating that manufacturing changes do not adversely affect product quality, safety, and efficacy. The guideline emphasized that the overall goal of comparability exercise is to ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of drug product produced by a changed manufacturing process, through collection and assessment of relevant data [2].

A significant advancement in Q5E was its more detailed discussion of the risk-based approach to comparability assessment, considering factors such as the extent of the manufacturing change, the stage of product development, and the relationship between quality attributes and safety and efficacy. The guideline also provided more specific guidance on the types of analytical studies needed, including assessments of product quality attributes such as physicochemical properties, biological activity, immunochemical properties, purity, and impurities [2]. While the 1996 FDA guidance had established the basic framework for comparability assessment, Q5E refined these concepts through international scientific consensus and reflected the accumulated experience with implementing comparability assessments across a range of biotechnology products.

Continued Relevance in Modern Context

Despite being issued nearly two decades ago, the ICH Q5E guideline remains the primary international standard for comparability assessment of biotechnology products, demonstrating the enduring relevance of its scientific principles [2]. The guideline's flexible, risk-based approach has proven adaptable to increasingly complex products and manufacturing technologies. Q5E established the important principle that comparability does not necessarily mean that the pre-change and post-change products are identical, but rather that they are highly similar and that any observed differences have no adverse impact on quality, safety, or efficacy [2].

The guideline also acknowledged that the amount and type of data needed to demonstrate comparability depends on the stage of product development, the scope of the manufacturing change, and the understanding of the product and its relationship to clinical outcomes. This nuanced approach has allowed the Q5E framework to remain applicable even as product complexity has increased, including for advanced therapy medicinal products such as cell and gene therapies. The enduring implementation of Q5E principles in regulatory practice worldwide demonstrates the success of this harmonized approach to maintaining product quality while enabling manufacturing innovation and improvement.

The 2025 Landscape: Novel Pathways and Updated Frameworks

The "Plausible Mechanism" Pathway for Personalized Therapies

A landmark development in 2025 has been the proposal of a novel regulatory approach termed the "plausible mechanism" (PM) pathway by FDA Commissioner Martin Makary and CBER Director Vinay Prasad [9]. This pathway aims to address unique challenges in the development of bespoke, personalized therapies, particularly in cases where traditional randomized trials are not feasible or practical. The PM pathway is structured as a phased operational model that begins with treating consecutive patients with personalized therapies, with the potential to progress toward marketing authorization after demonstrating success across several patients [9].

The FDA has outlined five key characteristics defining eligibility for the PM pathway:

- Identification of specific abnormality: A known and clear molecular or cellular abnormality with a direct causal link to the disease [9]

- Targeting underlying alteration: Interventions that directly target the proximate biological alteration rather than acting broadly on affected systems [9]

- Use of natural history data: Well-characterized natural history data for the disease in untreated populations [9]

- Evidence of target engagement: Confirmatory evidence showing successful targeting or editing of the intended biological target [9]

- Demonstration of clinical improvement: Evidence of durable improvements in clinical outcomes consistent with disease biology [9]

This pathway represents a significant regulatory innovation specifically designed for personalized therapies, particularly in the rare disease space where traditional development pathways face substantial practical and ethical challenges [9].

2025 Guidance Agenda and Policy Updates

The FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) has released an ambitious 2025 guidance agenda that includes multiple documents addressing contemporary challenges in biological product development [10]. The agenda reflects continued regulatory evolution across several key product areas, with particular emphasis on cell and gene therapies and advanced blood products. Notable planned guidances include:

Table: Selected 2025 CBER Guidance Agenda Items

| Product Category | Guidance Title | Focus Area | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Products | Potency Assurance for Cellular and Gene Therapy Products | Quality assessment for advanced therapies | New in 2025 |

| Therapeutic Products | Post Approval Methods to Capture Safety and Efficacy Data for Cell and Gene Therapy Products | Post-market evidence generation | New in 2025 |

| Blood and Blood Components | Recommendations for Evaluation of Devices Using Non-DEHP Materials | Safety of alternative materials | New in 2025 |

| Other | Recommendations for Validation and Implementation of Alternative Microbial Methods | Modernized testing approaches | New in 2025 |

Additionally, the FDA has been active in 2025 with safety communications and regulatory actions reflecting the ongoing lifecycle management of biological products [11] [12]. These include investigations into adverse events associated with specific products, new boxed warnings, and labeling changes based on emerging post-market safety data [12]. These actions demonstrate the continued emphasis on post-market surveillance and the application of a lifecycle approach to biological product regulation, consistent with the principles established in the original 1996 comparability guidance but adapted to contemporary products and risks.

Comparative Analysis: Evolution of Key Concepts

Changing Standards for Evidence

The evolution from the 1996 comparability guidance to the 2025 regulatory landscape reveals significant shifts in the types of evidence accepted for regulatory decision-making. The 1996 guidance established a primarily quality-focused approach to comparability, with progression to clinical studies only when analytical and preclinical data were insufficient to demonstrate comparability [8]. The 2005 ICH Q5E guideline reinforced this approach while providing greater international harmonization and detail on quality attribute assessment [2]. In contrast, the 2025 "plausible mechanism" pathway introduces greater flexibility in the evidence requirements for initial authorization, particularly for personalized therapies targeting rare diseases with high unmet need [9].

This evolution reflects a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between evidence types and regulatory decision-making contexts. While the fundamental principle of using the least burdensome approach to generate necessary evidence remains constant, the specific applications have expanded to address new product categories and development challenges. The table below illustrates key comparative aspects:

Table: Evolution of Key Regulatory Concepts from 1996 to 2025

| Aspect | 1996 Guidance | ICH Q5E (2005) | 2025 Updates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Manufacturing changes for established biologicals | Manufacturing changes for biotechnological products | Personalized therapies, rare diseases |

| Evidence Hierarchy | Analytical → Biological → Preclinical → Clinical | Quality → Nonclinical → Clinical (when needed) | Natural history → Target engagement → Clinical improvement |

| Clinical Data Requirements | Possibly waived with sufficient analytical data | Based on risk and product knowledge | May leverage real-world evidence and expanded access data |

| Post-Marketing Evidence | Not explicitly addressed | Mentioned for unresolved questions | Explicit requirement for ongoing data collection |

| Applicable Products | Human biologicals, therapeutic biotechnology products | Biotechnological/biological products | Cell and gene therapies, personalized interventions |

Adaptation to Novel Product Categories

The regulatory framework has demonstrated remarkable adaptability to new technologies over the past three decades. The 1996 guidance primarily addressed traditional biological products and therapeutic biotechnology-derived products [8], while the 2025 regulatory agenda explicitly encompasses cell and gene therapies, personalized treatments, and novel vaccine technologies [9] [10]. This expansion has required evolving approaches to fundamental concepts such as product characterization, potency assessment, and comparability demonstration.

For particularly challenging product categories such as cell-based therapies where full analytical characterization may be limited, the regulatory approach has evolved to incorporate additional elements such as functional potency assays, process validation, and in some cases, clinical data as part of the comparability assessment [10]. The 2025 guidance agenda includes specific documents addressing "Potency Assurance for Cellular and Gene Therapy Products" and "Post Approval Methods to Capture Safety and Efficacy Data for Cell and Gene Therapy Products," reflecting the continued evolution of regulatory thinking for these advanced modalities [10].

Practical Implementation: Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Design for Comparability Studies

Designing appropriate comparability studies requires careful consideration of the manufacturing change, product understanding, and relationship of quality attributes to clinical performance. The foundational approach from the 1996 guidance remains relevant: manufacturers should conduct side-by-side analyses of multiple pre-change and post-change lots using orthogonal analytical methods [8]. The experimental design should adequately power studies to detect clinically relevant differences, with statistical approaches appropriate for the analytical methodology being used.

For analytical comparability, a tiered approach is often employed where quality attributes are categorized based on their potential impact on safety and efficacy. Critical quality attributes that potentially impact clinical performance warrant more rigorous assessment with predefined acceptance criteria [8] [2]. The 1996 guidance emphasized that tests should include those routinely used for product release plus additional methods specifically designed to evaluate the impact of the specific manufacturing change, particularly focusing on manufacturing steps most likely affected by the change [8].

Advanced Methodologies for Novel Products

For complex biological products including cell and gene therapies, demonstrating comparability often requires specialized methodologies beyond conventional analytical approaches. The 2025 guidance agenda indicates continued attention to "Potency Assurance for Cellular and Gene Therapy Products," recognizing the unique challenges these products present [10]. Methodologies may include:

- Multi-parameter flow cytometry for cell surface marker characterization

- Next-generation sequencing approaches to evaluate genetic stability or vector integration sites

- Functional potency assays that measure biologically relevant responses

- Molecular characterization techniques to assess critical quality attributes

For products following the "plausible mechanism" pathway, methodologies to demonstrate target engagement become particularly important, potentially including biopsy assessments, molecular imaging, or biomarker evaluations [9]. The evidence of successful target editing or engagement may come from animal models, non-animal models, or clinical biopsies, with FDA potentially accepting evidence from a subset of patients or even the first-in-class subject dosed in certain cases [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing comparability assessments for biological products requires specialized reagents and materials that enable comprehensive characterization. The following table details key research solutions and their applications in comparability studies:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Comparability Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Function in Comparability Assessment | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Serve as benchmarks for side-by-side comparison of pre- and post-change products [8] | Quality attribute testing, bioassay normalization, method qualification |

| Characterized Cell Lines | Enable performance of relevant bioassays that reflect mechanism of action [8] | Potency assays, receptor binding studies, functional activity assessments |

| Quality-Characterized Antibodies | Facilitate specific detection and quantification of product and process-related impurities [8] | Immunoassays, Western blotting, impurity detection, host cell protein assays |

| Validated Assay Kits | Provide standardized approaches for critical quality attribute assessment | Glycan analysis, residual DNA quantification, endotoxin testing |

| Process-Related Impurity Standards | Allow detection and quantification of manufacturing process residuals | Host cell protein standards, chromatography resin leachables, antibiotic residues |

Regulatory Workflows: From Traditional Comparability to Novel Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the evolution of regulatory decision-making from the traditional comparability assessment to the novel plausible mechanism pathway:

The evolution of regulatory thinking from the 1996 comparability guidance to the 2025 updates demonstrates a consistent trajectory toward more nuanced, science-based approaches that balance innovation with appropriate regulatory oversight. The fundamental principle established in 1996—that manufacturing changes could be assessed through rigorous scientific evaluation without necessarily requiring additional clinical studies—has proven remarkably durable and adaptable [8]. This framework has expanded through international harmonization in ICH Q5E [2] and continues to evolve to address novel product categories and development challenges.

The 2025 regulatory landscape introduces important innovations, particularly the "plausible mechanism" pathway for personalized therapies [9] and updated guidance addressing contemporary challenges in cell and gene therapy development [10]. These developments reflect both continuity with established principles and adaptation to new scientific opportunities. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this evolutionary trajectory provides valuable context for navigating current regulatory expectations and anticipating future directions. The consistent theme across this nearly 30-year evolution is the commitment to scientific rigor coupled with appropriate regulatory flexibility, enabling continued innovation in biological products while maintaining standards for quality, safety, and efficacy.

The development and manufacturing of complex biological drugs operate on a fundamental principle distinct from traditional pharmaceuticals: the manufacturing process defines the product's inherent characteristics. For biologic drugs, which are large, complex molecules produced by living cells, the production process is inextricably linked to the final product's quality, efficacy, and safety. This whitepaper explores the scientific and regulatory foundations of this principle, detailing how process control, advanced analytics, and rigorous comparability exercises ensure that biologic products, including biosimilars, consistently meet their critical quality profiles.

Biological drugs, or biologics, represent a revolutionary class of therapeutics derived from living organisms. Unlike small-molecule drugs—which are simple, chemically synthesized compounds with well-defined structures—biologics are large, complex molecules, such as monoclonal antibodies, fusion proteins, and antibody-drug conjugates [13] [14]. A single monoclonal antibody can consist of over 25,000 atoms, making it orders of magnitude more complex than a drug like aspirin, which comprises only 21 atoms [14].

This structural complexity leads to an intrinsic challenge: inherent variability. Because biologics are produced by living cells in a multistep manufacturing process, they are impossible to replicate identically, even between batches of the same originator product [13] [14]. The living cell expression system imprints distinct post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as glycosylation, phosphorylation, and deamidation, which can generate millions of molecular variants of a single biologic [13]. These PTMs are not merely structural details; they can directly impact the biologic's clinical properties, including its potency, stability, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity [13]. Consequently, the biological activity of a therapeutic protein is defined not only by its amino acid sequence but also by the cell-based manufacturing process used to produce it [13].

The Scientific Foundation: How Process Defines Product

Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs)

The "process defines the product" paradigm is operationalized through the framework of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs).

- CQAs are physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that must be controlled within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality. They are the characteristics that have a direct impact on the product's efficacy or safety [13]. For a monoclonal antibody, dozens of CQAs may exist.

- CPPs are process parameters whose variability impacts CQAs and therefore must be monitored or controlled to ensure the process produces the desired product quality [15] [16].

The relationship is direct: controlling CPPs within predefined ranges ensures that CQAs remain within their specified limits. Table 1 summarizes key CQAs for a monoclonal antibody and their potential clinical impact.

Table 1: Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) of a Monoclonal Antibody and Their Clinical Impact

| Attribute Category | Specific CQA | Potential Impact on Efficacy/Safety |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | High-order structure, Disulfide bonds, Aggregates | Impacts potency; higher aggregates can lead to immunogenicity [13] |

| Charge Heterogeneity | Acidic/Basic forms, Deamidation, Oxidation | Can negatively impact potency [13] |

| Glycosylation Profile | Fucosylation, Mannosylation, Sialylation, Galactosylation | Alters effector functions (e.g., ADCC), pharmacokinetics (half-life), and can elicit immunogenic response [13] |

| Biological Activity | Binding to Fcγ receptors, FcRn affinity, ADCC, CDC | Directly impacts mechanism of action and pharmacokinetics [13] |

| Process Impurities | Host cell proteins, Protein A leachate, Host cell DNA | Can be toxic or elicit immunogenic response [13] |

The manufacturing process for biologics is a primary source of variability, influencing CQAs in two key areas:

- Upstream Process (Cell Culture): The conditions in the bioreactor—such as temperature, pH, nutrient levels, and dissolved gases—can significantly impact cell health and the PTMs of the expressed protein [13] [16]. For instance, subtle changes can induce protein aggregation or alter glycosylation patterns, which in turn affect safety and efficacy [13].

- Downstream Process (Purification and Formulation): Unit operations like Ultrafiltration/Diafiltration (UF/DF) are critical for concentrating the protein and exchanging it into the final formulation buffer. Inadequate control here can lead to inconsistencies in protein concentration or excipient levels, impacting the final drug substance [17].

The following diagram illustrates how the manufacturing process flow determines the final product quality through its impact on CQAs.

Diagram 1: The process-to-product relationship, showing how manufacturing steps influence CPPs, which in turn control CQAs to define final product quality.

Analytical and Experimental Methodologies for Process Control

Demonstrating control over the process requires a suite of advanced analytical technologies. The following experimental protocols and tools are essential for characterizing CQAs and monitoring CPPs.

Protocol 1: In-line Monitoring of Downstream UF/DF Using PAT

Objective: To monitor in real-time the concentration of the therapeutic protein and key excipients (e.g., trehalose) during the critical Ultrafiltration/Diafiltration (UF/DF) step [17].

Methodology:

- Technology: Implement a mid-infrared (MIR) spectroscopy-based Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tool (e.g., Monipa, Irubis GmbH) in-line on the UF/DF system.

- Principle: MIR spectroscopy detects the interaction of molecular bonds with light in the mid-infrared range (400–4000 cm⁻¹). Proteins absorb at 1600–1700 cm⁻¹ (amide I) and 1450–1580 cm⁻¹ (amide II), while excipients like trehalose absorb at 950–1100 cm⁻¹ [17].

- Procedure:

- The PAT probe is installed directly in the process stream.

- During the UF/DF process, the system continuously collects MIR spectra.

- The ultrafiltration (UF1) phase concentrates the protein, tracked via the amide I/II peaks.

- The diafiltration (DF) phase exchanges the buffer; the removal of original buffers and introduction of new excipients (e.g., trehalose) is tracked via their specific spectral fingerprints.

- A final ultrafiltration (UF2) phase concentrates the protein to its target drug substance concentration, which is verified in real-time.

- Validation: The real-time concentration data is validated against a reference method (e.g., SoloVPE), typically achieving an error margin of <5% for protein and <+1% for excipients like trehalose [17].

Protocol 2: Advanced Cell Health Monitoring in Upstream Processing

Objective: To move beyond basic viability measurements and detect early-stage apoptosis and cell aggregation to optimize bioreactor conditions [16].

Methodology:

- Technology: Use a dynamic imaging analyzer (e.g., Canty Dynamic Imaging System, DIA) coupled with an automated sampler (e.g., SegFlow).

- Principle: The DIA is a flow-through microscope that captures images of cells directly from the bioreactor. It uses a Support Vector Machines (SVM) algorithm trained on known cell images to classify cells based on 42 morphological features into categories: viable, necrotic, aggregated, and apoptotic [16].

- Procedure:

- An automated sampler draws a sample from the bioreactor and performs real-time dilution.

- The sample flows through the DIA, which captures high-resolution images of thousands of cells.

- The SVM model analyzes each cell's morphology to determine its health status.

- This allows for the detection of early apoptosis before the cell membrane is compromised—a stage invisible to traditional trypan blue exclusion methods [16].

- Advantage: Early detection of stress enables timely intervention (e.g., nutrient feeding, temperature shift) to prevent cell death and maintain productivity [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the above protocols requires specific tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| PAT Probe (MIR Spectroscopy) | Enables real-time, in-line monitoring of product and excipient concentrations during downstream processing by detecting molecule-specific infrared absorption [17]. |

| Dynamic Imaging Analyzer (DIA) | Provides high-resolution, flow-through imaging of cells for advanced morphological analysis, enabling early detection of apoptosis and cell aggregation [16]. |

| Automated Bioreactor Sampler | Automatically draws and dilutes samples from the bioreactor, ensuring consistent delivery to analytical instruments like the DIA while preserving fragile cell aggregates [16]. |

| Capacitance Probe | An in-line PAT tool that measures viable cell density and viable cell volume in the bioreactor by polarizing the culture and measuring charge retained by cells with intact membranes [16]. |

| Formulation Buffer Components | Excipients (e.g., histidine, trehalose) that stabilize the final drug substance. Their consistent concentration, achieved through controlled UF/DF, is a key CQA [17]. |

| SVM Algorithm Training Set | A pre-classified set of cell images (viable, necrotic, apoptotic) used to train the supervised learning model that powers the DIA's cell classification capabilities [16]. |

The Regulatory and Comparability Framework

The "process defines the product" principle is the cornerstone of the global regulatory framework for biologics, particularly for comparability assessments and biosimilar development.

Demonstrating Comparability After a Process Change

When a manufacturer changes the process for an approved biologic, it must demonstrate that the pre-change and post-change products are comparable. The foundation of this assessment is analytical comparability [18]. The goal is to show that the products are so similar in their CQAs that their clinical properties will be indistinguishable; clinical studies are seldom required [18]. This relies on:

- Orthogonal Analytical Methods: Using multiple, sensitive techniques (e.g., mass spectrometry plus chromatography) to cross-verify CQAs [18].

- Risk-based Weighting: Attributing more importance to CQAs with a direct known impact on clinical outcomes (e.g., primary structure must be identical, while minor glycoform variation may be acceptable) [18].

The Biosimilarity Exercise

A biosimilar is a biologic developed to be highly similar to an already licensed reference product. Its development is a focused, reverse-engineered comparability exercise [13] [14]. The following diagram outlines the step-wise approach to establishing biosimilarity, which places primary emphasis on analytical and functional comparisons.

Diagram 2: The step-wise biosimilar development pathway, demonstrating that analytical similarity is the foundation for approval.

The biosimilar developer must match the originator's "fingerprint" of CQAs as closely as possible using analytical tools that are more sensitive than clinical trials in detecting meaningful differences [13] [18]. Clinical studies for biosimilars are not designed to re-establish efficacy and safety from scratch, but to confirm sufficient likeness predicted by the analytical data [18] [14].

For complex biologics, the manufacturing process is not merely a production sequence—it is an intrinsic determinant of the product's identity. The principle that "the process defines the product" is driven by the inherent variability of molecules produced in living systems and the profound impact that process parameters have on Critical Quality Attributes. Maintaining consistent product quality requires a deep process understanding achieved through advanced Process Analytical Technologies, robust control strategies, and a rigorous risk-based approach to comparability. As the biologics and biosimilars market continues to evolve, adherence to this core principle, supported by convergent global regulatory standards, remains paramount for ensuring that patients receive medicines that are consistently safe, pure, and potent.

For researchers and drug development professionals working with biological products, the demonstration of comparability represents a fundamental scientific and regulatory requirement. The concept of comparability provides a structured framework for evaluating whether two versions of a biologic—whether the same product before and after a manufacturing change, or a biosimilar and its reference product—are sufficiently similar to ensure equivalent safety and efficacy profiles [18]. While both scenarios utilize the same foundational scientific principles of analytical and functional comparison, they differ significantly in their underlying context, knowledge base, and regulatory expectations [19].

This technical guide examines the critical distinctions between these two applications of comparability assessment, providing a detailed framework for designing appropriate studies within the context of biological products research. Understanding these distinctions is essential for efficiently allocating resources, designing scientifically valid studies, and meeting regulatory expectations for both innovator and biosimilar development programs.

Fundamental Conceptual Distinctions

Knowledge Base and Starting Points

The most fundamental distinction between these scenarios lies in the available knowledge about the manufacturing process and product understanding.

Manufacturing Process Changes: Occur within a single, controlled knowledge environment where the manufacturer possesses complete understanding of and historical data on the original manufacturing process, cell line, and product characteristics [19]. The manufacturer has established extensive knowledge of critical quality attributes (CQAs) and their acceptable ranges based on clinical experience with the original product.

Biosimilar Development: Begins with a significant knowledge gap regarding the reference product's proprietary manufacturing process [19] [20]. The biosimilar developer must reverse-engineer the reference product's critical attributes without access to the originator's manufacturing details, cell line, or process parameters, relying instead on extensive analytical characterization of the final product.

Regulatory Philosophies and Standards

The regulatory approaches for these two scenarios, while sharing scientific principles, differ in their fundamental questions and evidence requirements:

Manufacturing Process Changes: The central regulatory question is whether the change has adversely impacted the already approved product's safety, purity, and potency [8]. The burden of proof is demonstrating that differences, if any, have no adverse impact on the product's established clinical profile.

Biosimilar Development: The central question is whether the biosimilar candidate is highly similar to the reference product despite minor differences in clinically inactive components, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, and potency [19] [20]. The burden of proof is demonstrating similarity to a reference product with established efficacy and safety.

Table 1: Fundamental Conceptual Differences Between Scenarios

| Parameter | Manufacturing Process Change | Biosimilar Development |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Base | Complete process knowledge | Limited to public domain and analytical data |

| Cell Line | Same parental cell line | Different cell line |

| Starting Point | Well-characterized original product | Reference product characterization |

| Regulatory Standard | No adverse impact | High similarity |

| Evidence Threshold | Often analytical data sufficient | Totality of evidence across multiple study types |

Regulatory Frameworks and Guidelines

The comparability exercise for both scenarios operates within well-established regulatory frameworks that have evolved significantly since the 1990s [18].

Manufacturing Process Changes

For manufacturing changes, the ICH Q5E guideline provides the primary international framework for assessing comparability [2] [1]. This guideline outlines a risk-based approach where the scope of the manufacturing change dictates the extent of analytical studies required [19]. The FDA's 1996 guidance "Demonstration of Comparability of Human Biological Products" established the initial foundation, allowing manufacturers to implement changes without additional clinical studies when comparability could be demonstrated through analytical and functional testing [8].

The FDA's current approach for CMC changes to approved biological applications is detailed in the 2021 guidance "Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls Changes to an Approved Application: Certain Biological Products" [21]. This guidance employs a tiered-reporting system based on the potential impact of the change, ranging from prior-approval supplements to changes-being-effected supplements to annual reportable changes.

Biosimilar Development

The biosimilar pathway was established more recently, with the EU approving the first biosimilar (Omnitrope) in 2006 and the US following with the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 [18]. The FDA's comprehensive guidance "Development of Therapeutic Protein Biosimilars: Comparative Analytical Assessment and Other Quality-Related Considerations" outlines a stepwise approach to biosimilar development [20] [22].

This approach begins with extensive analytical characterization, moves through non-clinical assessments, and culminates in targeted clinical studies [20]. The "totality of the evidence" from these cumulative studies supports a demonstration of biosimilarity, with the analytical data forming the foundation of this assessment [22].

Methodological Approaches: Analytical and Statistical Assessment

Analytical Characterization Strategies

Both scenarios require extensive analytical characterization, but the breadth and depth differ significantly:

Manufacturing Process Changes: Analytical comparison focuses specifically on attributes potentially affected by the particular process change, utilizing historically qualified methods and established acceptance criteria based on prior knowledge and experience with the product [8].

Biosimilar Development: Requires comprehensive side-by-side analysis using orthogonal analytical techniques to compare structural, physicochemical, and functional attributes [20] [18]. This includes detailed assessment of primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure; post-translational modifications (particularly glycosylation); biological activity; impurities; and immunochemical properties [22].

Statistical Approaches for Comparability

A risk-based, tiered statistical approach is recommended for comparability assessments, particularly for biosimilars [23]. This framework classifies quality attributes based on their potential impact on safety and efficacy:

Table 2: Tiered Statistical Approaches for Comparability Assessment

| Tier | Application | Statistical Method | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) | Equivalence testing (TOST) or K-sigma comparison | Pre-defined equivalence margins (e.g., ±1.5σ) based on risk assessment |

| Tier 2 | Less critical quality attributes, in-process controls | Range testing | High percentage (85-95%) of biosimilar measurements within reference distribution limits |

| Tier 3 | Monitored parameters, qualitative assessments | Graphical comparison | Visual assessment for similar patterns and trends |

For Tier 1 CQAs, the equivalence test using two one-sided t-tests (TOST) is often employed to demonstrate that the mean difference between products falls within a pre-specified equivalence margin [23]. The K-sigma approach provides an alternative method where the absolute difference in means divided by the reference standard deviation must not exceed an acceptance limit (typically 1.5) [23].

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive comparability assessment workflow for both scenarios:

Experimental Design and Study Requirements

Study Scope and Clinical Data Requirements

The evidence requirements for both scenarios reflect their different knowledge bases and regulatory standards:

Manufacturing Process Changes: For many changes, especially those with limited scope, analytical studies alone may be sufficient to demonstrate comparability [19] [8]. Comparative clinical studies are typically required only for major changes that could potentially impact clinical performance, such as cell line changes [19].

Biosimilar Development: Requires a stepwise approach incorporating comparative analytical, non-clinical, and clinical studies [20]. Clinical comparisons typically begin with pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) studies, progressing to comparative clinical efficacy and safety trials in patients when necessary [20].

Risk Assessment and Weight of Evidence

A critical distinction lies in how evidence is weighted and interpreted:

Manufacturing Process Changes: The assessment employs prior knowledge of the product's characterization and clinical experience to focus on specific attributes potentially affected by the change [8]. The manufacturer can leverage historical data to establish meaningful acceptance criteria.

Biosimilar Development: Uses a risk-based system for weighting analytical data according to its relevance to clinical properties [18]. For the most critical attributes (e.g., primary protein structure), identicality is typically required, while wider variances may be acceptable for lower-weighted attributes [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful comparability assessment requires carefully selected reagents and methodologies. The following table outlines essential materials and their applications in comparability studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Comparability Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application in Comparability Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Benchmark for analytical comparisons | Quality control for both scenarios; primary comparator for biosimilars |

| Characterized Cell Banks | Production of biologic material | Same cell line for process changes; new but similar cell line for biosimilars |

| Chromatography Systems | Separation and analysis of product variants | Purity analysis, impurity profiling, charge variant assessment |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Structural characterization | Sequence confirmation, post-translational modification analysis |

| Biological Assay Reagents | Functional activity assessment | Cell-based assays, binding assays, enzyme activity measurements |

| Immunogenicity Assay Components | Detection of immune responses | Assessment of potential differences in immunogenic profiles |

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the critical distinctions between comparability assessment for manufacturing changes versus biosimilar development is essential for designing efficient, scientifically sound, and regulatory-compliant development programs. While both scenarios utilize the same advanced analytical technologies and statistical approaches, they differ fundamentally in their knowledge base, regulatory standards, and evidence requirements.

Manufacturing process changes benefit from complete process knowledge and historical data, often allowing demonstration of comparability through focused analytical studies. In contrast, biosimilar development must address significant knowledge gaps through comprehensive structural and functional characterization, employing a totality-of-the-evidence approach to demonstrate high similarity to the reference product.

As analytical technologies continue to advance, the sensitivity and reliability of comparability assessments will further improve, potentially reducing regulatory requirements for clinical data in both scenarios. However, the fundamental distinction between demonstrating "no adverse impact" for process changes and "high similarity" for biosimilars will continue to shape study design and regulatory expectations for biological products.

The totality of evidence approach represents a foundational paradigm in the development and evaluation of biological products, serving as a scientific bridge that connects analytical characterization with clinical performance. This systematic framework requires sponsors to develop a comprehensive body of evidence that convincingly demonstrates product comparability following manufacturing changes or establishes biosimilarity to a reference product. Unlike small-molecule drugs, biological products exhibit inherent complexity due to their large size, heterogeneous molecular structures, and sensitivity to manufacturing processes. Even minor alterations in production can potentially impact critical quality attributes (CQAs) that influence safety, purity, and potency [24]. The totality approach acknowledges this complexity by integrating data from multiple evidence streams—analytical studies, functional assays, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) evaluations, and comparative clinical studies—to form a conclusive scientific narrative about product similarity [24].

Regulatory agencies worldwide, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), recognize that biological products cannot be fully characterized by analytical methods alone. The totality of evidence approach provides a structured methodology for addressing residual uncertainty about product performance when a stepwise evaluation reveals no meaningful differences between the proposed product and its reference. This framework has evolved significantly over the past decade, with regulators gaining substantial experience in evaluating integrated data packages for biosimilar development and manufacturing changes [25] [26]. The approach continues to adapt to scientific advancements, particularly as analytical technologies become increasingly sensitive at detecting structural and functional characteristics [25].

Regulatory Framework and Evolution

Foundational Principles and Guidelines

The regulatory foundation for the totality of evidence approach stems from key guidance documents that outline scientific considerations for demonstrating biosimilarity and comparability. The ICH Q5E guideline establishes principles for assessing comparability of biotechnological/biological products after manufacturing changes, focusing on the collection of technical information that provides evidence that process changes do not adversely impact quality, safety, or efficacy [1]. This guideline emphasizes that comparability does not necessarily mean identical quality attributes but rather that the existing knowledge base adequately justifies the conclusion that no adverse impact occurs.

Similarly, FDA's "Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product" guidance, initially finalized in 2015 and updated in 2025, outlines a stepwise approach to biosimilar development that culminates in a totality-of-evidence assessment [25] [26]. The 2015 guidance recommended comparative efficacy studies (CES) if residual uncertainty remained after analytical, toxicity, PK, and immunogenicity assessments. However, the 2025 draft guidance represents a significant evolution in regulatory thinking, suggesting that for many therapeutic protein products (TPPs), CES may not be necessary when modern analytical technologies can provide sufficient characterization [25].

Recent Regulatory Developments

Recent regulatory updates reflect the FDA's growing confidence in advanced analytical methods as reliable tools for establishing biosimilarity and comparability. The October 2025 draft guidance marks a substantial shift by proposing that comparative efficacy studies may be unnecessary for certain well-characterized biological products when sufficient analytical and pharmacokinetic data exist [26]. This streamlined approach applies specifically to therapeutic protein products that meet three key conditions:

- The biosimilar and reference product are manufactured from clonal cell lines, are highly purified, and can be well-characterized analytically

- The relationship between quality attributes and clinical efficacy is well understood and can be evaluated by validated assays

- An appropriately designed human pharmacokinetic similarity study and immunogenicity assessment can address residual uncertainty [25] [26]

This evolution signals the FDA's recognition that comparative analytical assessments are often more sensitive than comparative efficacy studies for detecting clinically meaningful differences between products [25] [26]. The guidance reflects over a decade of regulatory experience evaluating biosimilar applications and acknowledges that analytical technologies can now structurally characterize highly purified therapeutic proteins and model in vivo functional effects with a high degree of specificity and sensitivity [25].

Table 1: Evolution of FDA's Approach to Evidence Requirements for Biosimilars

| Aspect | 2015 Guidance Approach | 2025 Draft Guidance Updates |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Data | Foundation, but often insufficient alone | May be sufficient with robust modern analytical techniques |

| Comparative Efficacy Studies | Generally expected unless scientifically unnecessary | May be unnecessary for well-characterized TPPs |

| Primary Evidence Source | Clinical studies | Comparative analytical assessment (CAA) |

| Residual Uncertainty | Addressed through clinical studies | Addressed through PK studies and immunogenicity assessment |

| Regulatory Mindset | Prove why CES isn't needed | Default to no CES when conditions met |

Core Components of the Totality of Evidence

Analytical Characterization

Comparative analytical assessment forms the cornerstone of the totality of evidence approach, providing the most sensitive tool for detecting structural and functional differences between biological products. The FDA's guidance "Development of Therapeutic Protein Biosimilars: Comparative Analytical Assessment and Other Quality-Related Considerations" emphasizes that analytical studies should comprehensively evaluate critical quality attributes (CQAs) that may impact safety, purity, and potency [22]. These attributes include primary structure (amino acid sequence), higher-order structure (folding), post-translational modifications (glycosylation patterns), biological activity, purity, and impurities [24].

The analytical comparability exercise must demonstrate that the proposed biosimilar or changed product is highly similar to the reference product notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive components [24]. Manufacturers must employ state-of-the-art analytical technologies—including mass spectrometry, chromatography, capillary electrophoresis, nuclear magnetic resonance, and various spectroscopic methods—to characterize both products extensively. The depth of analytical characterization required depends on product complexity, the understanding of structure-function relationships, and the capability of analytical methods to detect clinically relevant differences [22].

Functional and Nonclinical Studies

Functional assays provide critical evidence about biological activity and mechanism of action, serving as a bridge between analytical characterization and clinical performance. These in vitro studies evaluate the binding and functional properties of the product, including receptor binding affinity, signal transduction, effector functions, and other mechanism-relevant activities [24]. The assay validation is crucial, with sponsors expected to demonstrate that the methods are sufficiently sensitive to detect potential differences in functional activities that might impact clinical performance [22].

In some cases, animal studies may be necessary to address specific questions about toxicity, pharmacokinetics, or pharmacodynamics that cannot be adequately evaluated through in vitro methods alone [24]. However, the 2025 draft guidance indicates that for many well-characterized TPPs, the need for animal studies may be reduced when analytical and functional data provide sufficient evidence of similarity [25]. The determination of necessary nonclinical studies should be based on residual uncertainty after comprehensive analytical and functional assessment.

Clinical Studies

While the recent FDA draft guidance reduces the emphasis on comparative efficacy studies for certain products, clinical evaluation remains an essential component of the totality of evidence in many circumstances [25] [26]. The clinical development program typically includes:

- Pharmacokinetic studies comparing exposure metrics (AUC, Cmax) between the proposed and reference products

- Pharmacodynamic studies comparing biomarker responses when relevant PD markers exist

- Immunogenicity assessment evaluating potential differences in immune response

- Comparative efficacy and safety studies when residual uncertainty remains after other assessments [24]

The design of clinical studies should focus on sensitive populations and endpoints capable of detecting potential differences between products. For biosimilars, the clinical study goal is not to re-establish benefit-risk profile but to confirm similarity to the reference product [24]. When analytical and functional data are highly conclusive, clinical studies may be streamlined to focus primarily on pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity [25].

Table 2: Key Evidence Components in a Totality of Evidence Approach