Ensuring Trust in Single-Cell Biology: A Comprehensive Framework for Cell Type Annotation Credibility Assessment

Accurate cell type annotation is the critical foundation for all downstream single-cell RNA sequencing analysis, yet ensuring its reliability remains a significant challenge.

Ensuring Trust in Single-Cell Biology: A Comprehensive Framework for Cell Type Annotation Credibility Assessment

Abstract

Accurate cell type annotation is the critical foundation for all downstream single-cell RNA sequencing analysis, yet ensuring its reliability remains a significant challenge. This article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for assessing annotation credibility, covering foundational principles, emerging methodologies like Large Language Models (LLMs), practical troubleshooting strategies, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest advancements in automated tools, reference-based methods, and objective credibility evaluation, we offer a actionable pathway to enhance reproducibility, identify novel cell types, and build confidence in cellular research findings for biomedical and clinical applications.

Why Cell Type Annotation Fails: Understanding the Core Challenges in Single-Cell Biology

Cell type annotation serves as the foundational step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, determining how we interpret cellular heterogeneity, function, and dysfunction in health and disease. The credibility of this initial annotation directly dictates the reliability of all subsequent biological conclusions, from identifying novel therapeutic targets to understanding disease mechanisms. Despite its critical importance, the field currently grapples with a significant challenge: the pervasive risk of annotation errors that systematically propagate through downstream analyses. Traditional annotation methods, whether manual expert curation or automated reference-based approaches, carry inherent limitations that compromise their reliability. Manual annotation suffers from subjective biases and inter-rater variability [1] [2], while automated tools often depend on constrained reference datasets that may not fully capture the biological complexity of new samples [3] [4]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning have introduced transformative solutions, yet simultaneously raised new questions about verification, reproducibility, and objective credibility assessment. This guide examines the high-stakes implications of annotation errors through a systematic comparison of emerging computational methods, providing researchers with experimental frameworks for implementing robust, credible annotation pipelines in their own work.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Annotation Methods

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Platforms

Comprehensive evaluation of cell type annotation tools requires standardized assessment across diverse biological contexts. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of major annotation approaches based on recent benchmarking studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cell Type Annotation Methods

| Method | Approach | Accuracy Range | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LICT | Multi-LLM integration with credibility evaluation | 90.3-97.2% (high heterogeneity) [1] | Reference-free; objective reliability scoring; handles multifaceted cell populations | Performance decreases with low-heterogeneity datasets (51.5-56.2% mismatch) [1] |

| STAMapper | Heterogeneous graph neural network | Best performance on 75/81 datasets [3] | Excellent with low gene counts (<200 genes); batch-insensitive | Requires paired scRNA-seq reference data [3] |

| GPTCelltype | Single LLM (GPT-4) | >75% full/partial match in most tissues [5] | Cost-efficient; integrates with existing pipelines; broad tissue applicability | Limited reproducibility (85% for identical inputs) [5] |

| NS-Forest | Random forest feature selection | N/A (marker discovery) | Identifies minimal marker combinations; enriches binary expression patterns | Not a direct annotation tool; requires downstream validation [6] |

| scMapNet | Vision transformer with treemap charts | Superior to 6 competing methods [7] | Batch insensitive; biologically interpretable; discovers novel biomarkers | Requires transformation of scRNA-seq to image-like data [7] |

| Reference-based (SingleR, ScType) | Correlation-based matching | Lower than GPT-4 based on agreement scores [5] | Leverages well-curated references; established workflows | Limited by reference quality; poor with novel cell types [4] [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

To ensure credible annotations, researchers should implement standardized validation protocols. The following experimental frameworks have been employed in recent methodological studies:

Benchmarking Protocol for Annotation Tools

- Dataset Curation: Collect diverse scRNA-seq datasets representing various biological contexts (normal physiology, development, disease states) and technological platforms (10X Genomics, Smart-seq2) [1] [4] [5]. Include datasets with manual annotations from domain experts as ground truth references.

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate using multiple metrics including accuracy, macro F1 score (for imbalanced cell type distributions), and weighted F1 score [3]. Calculate agreement scores between automated and manual annotations [5].

- Heterogeneity Assessment: Test methods across cell populations with varying heterogeneity levels, including high-heterogeneity (e.g., PBMCs) and low-heterogeneity (e.g., stromal cells, embryos) datasets [1].

- Robustness Testing: Evaluate performance under challenging conditions such as down-sampled gene counts, simulated noise contamination, and identification of rare cell types [3] [5].

- Credibility Validation: For LLM-based methods, implement objective credibility assessment through marker gene expression validation, where annotations are deemed reliable if >4 marker genes are expressed in ≥80% of cells within the cluster [1] [2].

LICT-Specific Validation Workflow

- Multi-Model Integration: Generate independent annotations from five top-performing LLMs (GPT-4, LLaMA-3, Claude 3, Gemini, ERNIE 4.0) and select the best-performing results [1].

- Talk-to-Machine Iteration: For discordant annotations, query LLMs for representative marker genes, validate expression patterns in the dataset, and provide structured feedback with additional differentially expressed genes for re-annotation [1] [2].

- Objective Credibility Evaluation: Assess final annotation reliability through marker gene retrieval and expression pattern evaluation independent of manual annotations [1].

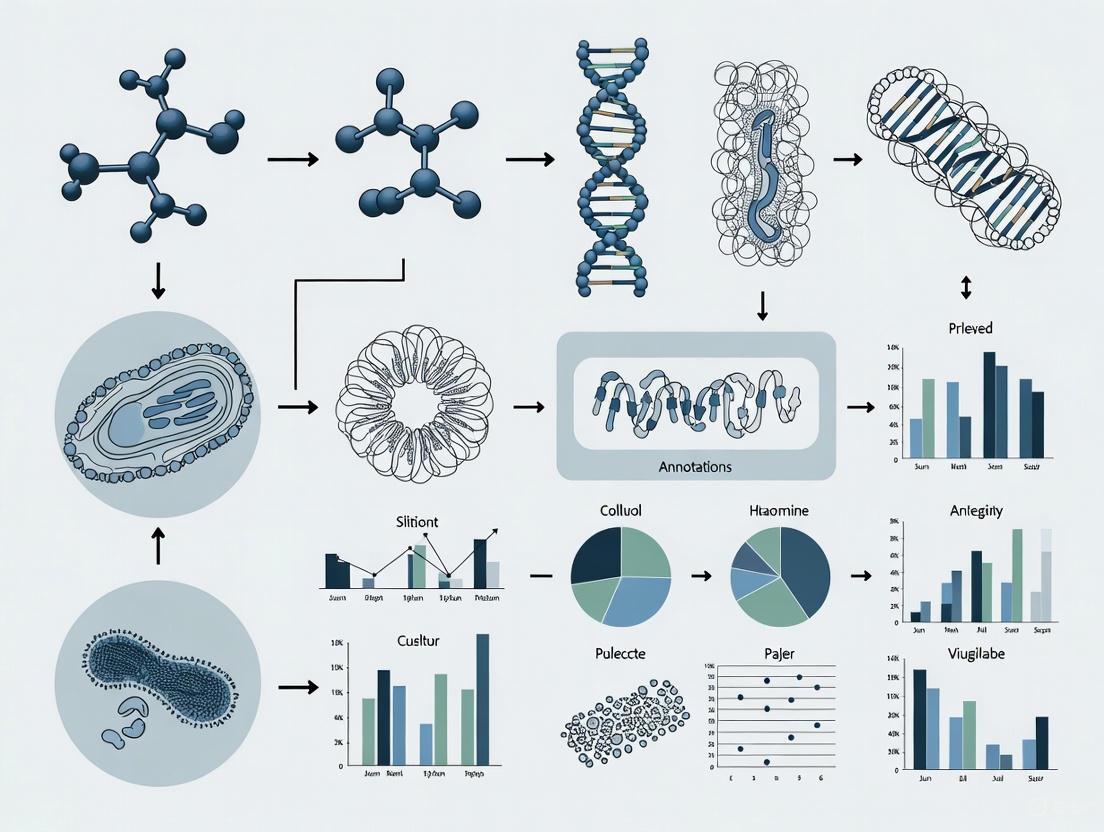

Figure 1: Cell Type Annotation Workflows and Error Propagation Pathways. This diagram illustrates three major annotation approaches (LLM-based, reference-based, and deep learning) and how errors at any stage propagate to downstream biological conclusions.

The Impact of Annotation Errors on Biological Interpretation

Case Studies in Error Propagation

Annotation inaccuracies systematically distort biological interpretation across multiple research contexts. In cancer research, misannotation of stromal cell subtypes has led to flawed understanding of tumor microenvironment composition. When manual annotations broadly classified cells as "stromal cells," GPT-4 provided more granular identification distinguishing fibroblasts and osteoblasts based on type I collagen gene expression versus chondrocytes expressing type II collagen genes [5]. This refinement revealed previously obscured cellular heterogeneity with significant implications for understanding stromal contributions to tumor progression.

In developmental biology studies, annotation errors particularly affect low-heterogeneity cell populations. Evaluation of LLM performance revealed significantly higher discrepancy rates in human embryo (39.4-48.5% consistency) and stromal cell datasets (33.3-43.8% consistency) compared to high-heterogeneity populations like PBMCs [1]. These inaccuracies in developmental systems can lead to fundamental misunderstandings of lineage specification and cellular differentiation pathways.

Spatial transcriptomics presents unique annotation challenges where traditional methods often fail at cluster boundaries. STAMapper demonstrated enhanced performance over manual annotations specifically at these problematic boundaries, enabling more accurate cell-type mapping in complex tissue architectures [3]. In neurological research, NS-Forest's identification of minimal marker combinations revealed the importance of cell signaling and noncoding RNAs in neuronal cell type identity, aspects frequently overlooked by conventional annotation approaches [6].

Systematic Consequences in Downstream Analysis

Table 2: Downstream Impacts of Annotation Errors

| Research Domain | Impact of Annotation Errors | Credible Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Cell Interaction | Mischaracterization of communication networks; false signaling pathways | Multi-model integration with objective credibility scoring [1] |

| Differential Expression | Incorrect cell-type specific markers; false therapeutic targets | Binary expression scoring with precision weighting [6] |

| Disease Mechanism | Erroneous cellular drivers of pathology; flawed disease subtyping | Graph neural networks with batch correction [3] |

| Developmental Trajectory | Inaccurate lineage reconstruction; misguided progenitor identification | Talk-to-machine iterative validation [1] [2] |

| Therapeutic Development | Misguided target identification; clinical trial failures | Marker-based validation with expression pattern evaluation [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Databases

Implementation of credible annotation pipelines requires leveraging curated biological knowledge bases and computational resources. The following table details essential research reagents for establishing robust annotation workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Credible Cell Type Annotation

| Resource | Type | Function in Annotation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CellMarker 2.0 [4] | Marker Gene Database | Provides canonical marker genes for manual and automated annotation | Cross-tissue validation; hypothesis generation |

| PanglaoDB [4] | Marker Gene Database | Curated resource for cell type signature genes | Reference-based annotation; method benchmarking |

| NS-Forest [6] | Algorithm | Discovers minimal marker gene combinations with binary expression | Optimal marker selection for experimental validation |

| Human Cell Atlas [4] | Reference Atlas | Comprehensive map of human cell types | Reference-based annotation; novel cell type detection |

| Tabula Muris [4] | Reference Atlas | Multi-organ mouse cell type reference | Cross-species validation; model organism studies |

| LICT [1] [2] | Annotation Tool | LLM-based identifier with credibility assessment | Reference-free annotation; objective reliability scoring |

| STAMapper [3] | Annotation Tool | Heterogeneous graph neural network for spatial data | Spatial transcriptomics; low gene count scenarios |

| GPTCelltype [5] | Annotation Tool | GPT-4 interface for automated annotation | Rapid prototyping; integration with Seurat pipelines |

The high stakes of cell type annotation demand rigorous methodological standards and credibility assessment frameworks. Through comparative analysis of emerging computational approaches, several principles for credible annotation practice emerge. First, multi-model integration strategies significantly enhance reliability by leveraging complementary strengths of diverse algorithms [1]. Second, iterative validation mechanisms like the "talk-to-machine" approach provide critical safeguards against annotation errors [1] [2]. Third, objective credibility evaluation independent of manual annotations offers essential quality control, particularly important given the documented limitations of expert-based curation [1]. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve toward increasingly complex multi-omics applications, establishing these credible annotation practices will become increasingly critical for ensuring the biological insights driving therapeutic development accurately reflect underlying cellular realities rather than methodological artifacts.

Cell type annotation is a critical step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis, bridging the gap between computational clustering and biological interpretation. For years, the field has relied primarily on two paradigms: manual expert annotation, which depends on an annotator's knowledge and prior experience but introduces subjectivity, and reference-based automated methods, which offer scalability but are constrained by the composition and quality of their training data [1] [8]. This dependence creates a significant challenge for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of cellular research, particularly when novel or rare cell types are present.

The core of the problem lies in the inherent limitations of these traditional approaches. Manual annotation is vulnerable to inter-rater variability and systematic biases [1], while reference-based tools can produce misleading predictions if the query data contains cell types not represented in the reference atlas—so-called "unseen" cell types [9]. These limitations underscore the need for objective frameworks to assess annotation credibility independently of potentially flawed ground truths. This guide evaluates emerging solutions that address these foundational challenges, focusing on their performance, methodologies, and practical utility for the research scientist.

Performance Benchmarking of Modern Annotation Tools

To objectively compare the capabilities of newer annotation strategies against traditional and contemporary alternatives, we benchmarked several tools across multiple datasets. The evaluation included LICT (Large language model-based Identifier for Cell Types), which employs a multi-LLM fusion and a "talk-to-machine" interactive approach [1]; mtANN (multiple-reference-based scRNA-seq data annotation), which integrates multiple references to identify unseen cell types [9]; and ScInfeR (Single Cell-type Inference toolkit using R), a hybrid graph-based method that combines information from both scRNA-seq references and marker sets [10]. These were assessed on their accuracy in annotating diverse biological contexts, including highly heterogeneous samples like Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) and lower-heterogeneity environments like stromal cells and embryonic datasets [1] [9].

Table 1: Overall Annotation Performance Across Diverse Tissue Types

| Tool | Underlying Strategy | PBMC Dataset (Match Rate) | Gastric Cancer Dataset (Match Rate) | Stromal Cell Dataset (Match Rate) | Unseen Cell Type Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LICT | Multi-LLM Integration & "Talk-to-Machine" [1] | 90.3% [1] | 91.7% [1] | 43.8% (Full Match) [1] | Not Explicitly Tested |

| mtANN | Multiple Reference & Ensemble Learning [9] | High (Precise rates dataset-dependent) [9] | High (Precise rates dataset-dependent) [9] | High (Precise rates dataset-dependent) [9] | Supported [9] |

| ScInfeR | Hybrid (Reference + Marker Graph) [10] | Superior in benchmark studies [10] | Superior in benchmark studies [10] | Superior in benchmark studies [10] | Supported via hybrid approach [10] |

| GPTCelltype | Single LLM (GPT-4) [1] | 78.5% [1] | 88.9% [1] | Low [1] | Not Supported |

The quantitative data reveals a clear efficiency gain for modern tools. LICT's multi-model strategy significantly reduced the mismatch rate in PBMC data from 21.5% (using a single LLM) to 9.7%, establishing its superiority over simpler LLM implementations like GPTCelltype [1]. Furthermore, its interactive "talk-to-machine" strategy boosted the full match rate for gastric cancer data to 69.4%, while reducing mismatches to 2.8% [1]. Although all tools perform well on heterogeneous data, the annotation of low-heterogeneity cell types (e.g., stromal cells and embryos) remains a challenge, with even the best tools showing considerable room for improvement [1].

Table 2: Performance on Low-Heterogeneity and Challenging Datasets

| Tool | Human Embryo Dataset (Match Rate) | Key Strength | Objective Reliability Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| LICT | 48.5% (Full Match) [1] | Objective credibility evaluation without reference data [1] | Yes (Via marker gene validation) [1] |

| mtANN | High (Precise rates dataset-dependent) [9] | Accurate identification of unseen cell types with multiple references [9] | No |

| ScInfeR | Superior in benchmark studies [10] | Versatility across scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, and spatial omics [10] | No |

| Manual Expert Annotation | Used as a benchmark, but shows low objective reliability scores [1] | Domain knowledge integration | No (Inherently subjective) [1] |

A critical finding from these benchmarks is that discrepancy from manual annotation does not necessarily indicate an error by the automated tool. In the stromal cell dataset, LICT's objective evaluation found that 29.6% of its own mismatched annotations were credible based on marker gene expression, whereas none of the conflicting manual annotations met the same credibility threshold [1]. This highlights the potential of objective, data-driven credibility assessment to overcome the subjectivity inherent in manual curation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

LICT: Multi-Model Integration and Interactive Validation

The LICT framework is built on three core strategies designed to enhance the reliability of LLMs for cell type annotation [1].

- Multi-Model Integration: Instead of relying on a single LLM, LICT leverages the complementary strengths of five top-performing models (GPT-4, LLaMA-3, Claude 3, Gemini, and ERNIE 4.0) selected from an initial evaluation of 77 candidates. For each cell cluster, the best-performing annotation from any of the five models is selected, creating a robust consensus that outperforms any single model [1].

- "Talk-to-Machine" Strategy: This is an iterative human-computer interaction process designed to refine annotations. The workflow starts with an initial annotation, then the LLM is queried for representative marker genes for the predicted cell type. The expression of these genes is evaluated in the input dataset. If the validation fails (fewer than four marker genes expressed in 80% of cells), the LLM is provided with the validation results and additional differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and is prompted to revise its annotation [1].

- Objective Credibility Evaluation: This final strategy provides a reference-free method to assess the reliability of any annotation, whether generated by an LLM or a human expert. It follows a similar process to the validation step above: retrieving marker genes for the annotated cell type and checking their expression in the dataset. An annotation is deemed reliable if the marker gene expression threshold is met, providing a quantitative measure of confidence independent of the original annotation method [1].

mtANN: Ensemble Learning for Unseen Cell Type Detection

The mtANN methodology addresses the critical issue of unseen cell types through a multi-reference, ensemble learning approach [9]. Its workflow can be divided into a training and a prediction process.

- Module I: Diverse Gene Selection. Eight different gene selection methods (DE, DV, DD, DP, BI, GC, Disp, Vst) are applied to each reference dataset to generate multiple subsets of informative genes. This increases data diversity and facilitates the detection of biologically important features for robust ensemble learning [9].

- Module II: Base Classifier Training. A collection of neural network-based deep classification models are trained on the various reference subsets generated in Module I. These base models learn complementary relationships between gene expression and cell types [9].

- Module III: Metaphase Annotation via Majority Voting. The trained base classifiers make predictions on the query data. A metaphase (interim) annotation for each cell is obtained by taking a majority vote from all the base model predictions [9].

- Module IV: Uncertainty Metric Formulation. A novel metric is computed to identify cells likely belonging to unseen types. This metric considers three complementary aspects of uncertainty: intra-model (average entropy of prediction probabilities from individual classifiers), inter-model (entropy of the averaged probabilities across all models), and inter-prediction (inconsistency among the discrete labels predicted by the base models) [9].

- Module V: Unseen Cell Identification. A Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) is fitted to the combined uncertainty metric from Module IV. Cells falling into the component with high predictive uncertainty are flagged as "unassigned," representing the potential unseen cell types [9].

ScInfeR: A Hybrid Graph-Based Framework

ScInfeR distinguishes itself by combining marker-based and reference-based approaches within a unified graph-based framework, enabling versatile annotation across multiple omics technologies [10].

- Dual Input and Marker Extraction. ScInfeR can accept user-defined marker sets, a scRNA-seq reference dataset, or both. When a reference is provided, it automatically extracts cell-type-specific marker genes by evaluating both global and local specificity of gene expression [10].

- Graph Construction and Initial Annotation. A cell-cell similarity graph is built based on gene expression profiles. In the first round of annotation, cell clusters are labeled by correlating cluster-specific markers with the provided cell-type-specific markers within this graph. The tool supports weighted positive and negative markers, allowing users to emphasize the importance of certain genes in the classification [10].

- Hierarchical Subtype Classification. A second, hierarchical round of annotation is performed to identify cell subtypes and resolve clusters containing multiple cell types. This step uses a framework adapted from message-passing layers in Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to annotate each cell individually, improving the resolution of closely related cell subtypes [10].

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the LICT tool, showcasing the synergy between its three core strategies.

LICT Integrated Workflow

The mtANN framework employs a sophisticated pipeline for identifying unseen cell types using multiple references, as detailed below.

mtANN Unseen Cell Identification

For researchers seeking to implement or benchmark these advanced annotation methods, the following table details key resources and computational tools referenced in the evaluated studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Type Annotation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Annotation | Relevant Tool(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC (GSE164378) [1] | scRNA-seq Dataset | A benchmark dataset of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells, widely used for evaluating annotation tools due to well-defined cell populations. | LICT, mtANN, ScInfeR |

| Tabula Sapiens Atlas [10] | scRNA-seq Reference Atlas | A comprehensive, multi-tissue scRNA-seq atlas providing high-quality ground truth annotations for benchmarking. | ScInfeR, mtANN |

| ScInfeRDB [10] | Marker Gene Database | An interactive database containing manually curated markers for 329 cell types, covering 28 human and plant tissues. | ScInfeR |

| Gastric Cancer Dataset [1] | scRNA-seq Dataset | A disease-state dataset used to validate annotation performance in a pathological context. | LICT |

| Human Embryo Dataset [1] | scRNA-seq Dataset | A developmental biology dataset representing a lower-heterogeneity cellular environment for challenging annotation tests. | LICT |

| Top-Performing LLMs (GPT-4, LLaMA-3, Claude 3) [1] | Computational Model | Large Language Models that provide foundational knowledge for marker gene interpretation and cell type prediction. | LICT |

The landscape of cell type annotation is rapidly evolving beyond the traditional dichotomy of manual expertise and rigid reference databases. Tools like LICT, mtANN, and ScInfeR represent a paradigm shift towards more objective, reliable, and self-assessing computational frameworks. LICT's multi-model LLM approach and objective credibility evaluation mitigate the subjectivity of manual annotation and the constraints of single-reference bias. mtANN's ensemble learning strategy directly addresses the critical problem of unseen cell types, reducing false predictions and facilitating novel discoveries. ScInfeR's hybrid model leverages the complementary strengths of reference and marker-based methods, offering versatility across diverse omics technologies.

For the modern researcher, the choice of tool should be guided by the specific experimental context and the paramount need for credibility assessment. When working with well-established cell types in a well-annotated system, multiple approaches may suffice. However, when venturing into novel tissues, disease states, or developmental stages—where cellular heterogeneity is not fully mapped—employing tools with built-in mechanisms for identifying uncertainty and validating annotations internally becomes crucial. The continued development and integration of such objective frameworks are essential for building a more reproducible and trustworthy foundation for single-cell biology.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling high-resolution analysis of cellular heterogeneity, profoundly impacting cancer research, immunology, and developmental biology [11]. However, this powerful technology introduces significant technical challenges that can compromise the credibility of research findings, particularly in cell type annotation—a fundamental step in single-cell analysis. The growing reliance on single-cell technologies for critical applications, including drug development and clinical diagnostics, makes rigorous assessment of these technical pitfalls an essential component of research methodology.

This guide examines three major technical factors affecting data quality and analytical outcomes: sequencing platform selection, data sparsity, and batch effects. We provide objective comparisons of experimental platforms and computational methods based on recent benchmarking studies, equipping researchers with the knowledge to assess and mitigate these challenges in their cell type annotation workflows. By understanding how these technical variables influence analytical outcomes, researchers can design more robust studies and critically evaluate single-cell research claims.

Sequencing Platform Performance: Technical Comparisons

Commercial Platform Specifications and Applications

Single-cell sequencing platforms employ distinct technological approaches that significantly impact data quality, cost, and applicability to different sample types. Understanding these differences is crucial for appropriate experimental design and credible cell type annotation.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Single-Cell Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Technology | Throughput (cells/run) | Cell Capture Efficiency | Key Strengths | Sample Compatibility | Species Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Droplet microfluidics | ~80,000 (8 channels) | ~65% | High throughput, strong reproducibility | Fresh, frozen, gradient-frozen, FFPE | Human, mouse, rat, other eukaryotes |

| 10x Genomics FLEX | Droplet microfluidics | Up to 1 million (multiplexed) | Similar to Chromium | FFPE compatibility, sample multiplexing | FFPE, PFA-fixed samples | Human, mouse, rat, other eukaryotes |

| BD Rhapsody | Microwell with magnetic beads | Customizable | Up to 70% | Protein+RNA profiling, lower viability tolerance (~65%) | Fresh, frozen, low-viability samples | Human, mouse, rat, other eukaryotes |

| MobiDrop | Droplet-based | Adjustable | Not specified | Cost-effective, automated workflow | Fresh, frozen, FFPE | Human, mouse, rat, other eukaryotes |

The 10x Genomics Chromium system remains the most widely adopted platform globally, often chosen by more than 80% of researchers for its balanced performance in throughput and reproducibility [11]. Its droplet-based microfluidics design enables robust cell partitioning and consistent library preparation. The newer FLEX variant extends these capabilities to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, unlocking valuable archival clinical material for single-cell analysis [11].

BD Rhapsody employs a distinctive microwell-based approach with 200,000 wells (50μm diameter) combined with 35μm magnetic barcoded beads. This technology provides approximately 70% cell capture efficiency—among the highest in the field—and tolerates cell viability as low as 65%, making it particularly suitable for challenging clinical samples [11]. A key advantage is its native compatibility with combined transcriptomic and proteomic profiling (CITE-seq, AbSeq), allowing simultaneous measurement of surface protein markers alongside gene expression.

MobiDrop emphasizes cost efficiency and workflow flexibility, offering lower per-cell reagent costs compared to other droplet-based systems. This platform integrates cell capture, library preparation, and nucleic acid extraction into a streamlined automated workflow, reducing technical variability [11].

Sequencing Instrument Performance

Beyond cell partitioning systems, the sequencing instruments themselves significantly impact data quality and cost. Recent benchmarking compares established platforms like Illumina with emerging technologies like Ultima Genomics, which promises substantial cost reductions.

Table 2: Sequencing Platform Performance for Single-Cell Applications

| Sequencing Platform | Application | Data Quality Findings | Compatibility | Cost Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X Plus | 10x 3' and 5' libraries | Reference standard | Native compatibility with 10x | Standard |

| Ultima Genomics UG 100 | 10x 3' and 5' libraries | Comparable sequencing depths after analysis; Lower Q scores not indicative of poorer data quality | Viable option after batch correction for 5' libraries | Potential for significant cost reduction |

A 2025 white paper evaluating Illumina NovaSeq X Plus and Ultima Genomics UG 100 for 10x Genomics single-cell RNA sequencing found that after Cell Ranger analysis, sequencing depths were comparable between platforms [12]. Although the UG 100 exhibited lower Q scores, these did not translate to poorer data quality in downstream analyses. For 3' gene expression libraries, cell clustering was consistent across platforms without batch correction. The 5' libraries required batch correction and adjusted filtering settings but ultimately produced comparable results [12]. These findings position Ultima Genomics as a cost-effective alternative for large-scale single-cell projects without substantial quality compromises.

Data Sparsity: The Zero-Inflation Challenge

Understanding the Nature of Zeros in Single-Cell Data

Single-cell RNA sequencing data is characterized by a high proportion of zero counts, presenting significant challenges for differential expression analysis and cell type annotation. The "curse of zeros" represents a fundamental challenge in scRNA-seq, as zero counts can arise from three distinct scenarios: (1) genuine biological zeros (the gene is not expressed), (2) sampled zeros (the gene is expressed at low levels), or (3) technical zeros (the gene is expressed but not captured) [13].

The prevailing assumption in the single-cell community has been that zeros primarily represent technical artifacts or "drop-outs." This has led to widespread use of pre-processing steps aimed at removing zero inflation, including aggressive gene filtering (requiring non-zero values in at least 10% of cells), zero imputation, and specialized zero-inflation models [13]. However, growing evidence suggests that cell-type heterogeneity is actually the major driver of zeros in 10x UMI data [13]. Consequently, standard zero-handling approaches may inadvertently discard biologically meaningful information, particularly for rare cell types where distinctive marker genes may be precisely those with high zero rates in other cell populations.

Impact of Normalization on Data Interpretation

Normalization procedures dramatically impact data distribution and can introduce artifacts that affect downstream cell type annotation. A 2025 study demonstrated that different normalization methods—CPM, sctransform VST, and Seurat CCA integration—profoundly alter both non-zero and zero count distributions [13].

For example, library size normalization methods like CPM (counts per million) convert UMI data from absolute to relative abundances, erasing biologically meaningful information about absolute RNA content differences between cell types. In one fallopian tube dataset, macrophages and secretory epithelial cells exhibited significantly higher RNA content than other cell types—a biologically meaningful difference that was eliminated by CPM normalization [13]. Similarly, variance-stabilizing transformation (sctransform) and batch integration methods transform zero counts to non-zero values, potentially obscuring true biological signals.

The generalized Poisson/Binomial mixed-effects model (GLIMES) framework has been proposed as an alternative approach that leverages UMI counts and zero proportions while accounting for batch effects and within-sample variation [13]. This method preserves absolute RNA expression information rather than converting to relative abundance, potentially improving sensitivity and reducing false discoveries in differential expression analysis.

Batch Effects: Integration Challenges and Solutions

The Batch Effect Problem in Single-Cell Studies

Batch effects—systematic technical variations between experiments—represent a major challenge for integrating single-cell datasets across samples, studies, and platforms. These effects can profoundly impact cell type annotation, particularly as the field moves toward large-scale atlas projects that combine diverse datasets [14].

The severity of batch effects varies considerably across experimental scenarios. While most integration methods perform adequately for batches processed similarly within a single laboratory, they struggle with substantial batch effects arising from different biological systems (e.g., species, organoids vs. primary tissue) or technologies (e.g., single-cell vs. single-nuclei RNA-seq) [14]. In such cases, the distance between samples of the same cell type from different systems can significantly exceed distances within systems, complicating integration.

Benchmarking Integration Methods

Deep Learning Approaches

Deep learning methods have emerged as powerful tools for single-cell data integration, with variational autoencoders (VAE) being particularly prominent. A 2025 benchmark evaluated 16 deep learning integration methods within a unified VAE framework, incorporating different loss functions for batch correction and biological conservation [15].

The benchmark revealed limitations in current evaluation metrics, particularly the single-cell integration benchmarking (scIB) index, which may not adequately capture preservation of intra-cell-type biological variation. To address this, researchers proposed scIB-E, an enhanced benchmarking framework with improved metrics for biological conservation [15]. They also introduced a correlation-based loss function that better preserves biological signals during integration.

Performance varies significantly across methods and application contexts. For standard integration tasks (e.g., within similar tissues), scVI provides a robust baseline. For more challenging integration scenarios involving substantial biological differences, scANVI incorporating some cell type annotations often improves performance. The newly proposed sysVI method, which combines VampPrior and cycle-consistency constraints, shows particular promise for integrating datasets with substantial batch effects while preserving biological signals [14].

Differential Expression Analysis with Batch Effects

Batch effects significantly impact differential expression analysis, a critical step for identifying marker genes used in cell type annotation. A comprehensive benchmark of 46 differential expression workflows for multi-batch single-cell data revealed that:

- The use of batch-corrected data rarely improves differential expression analysis for sparse data

- Batch covariate modeling improves analysis for substantial batch effects but may slightly deteriorate performance for minimal batch effects

- For low-depth data, single-cell techniques based on zero-inflation models deteriorate performance, whereas analysis of uncorrected data using limmatrend, Wilcoxon test, and fixed effects models performs well [16]

The performance of different strategies depends heavily on sequencing depth. For moderate depths (average nonzero count ~77), parametric methods (MAST, DESeq2, edgeR, limmatrend) and their covariate models generally perform well. For very low depths (average nonzero count ~4), the benefit of covariate modeling diminishes, and simpler approaches like Wilcoxon test on log-normalized data show enhanced relative performance [16].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Benchmarking Experimental Design

Rigorous benchmarking of computational methods requires carefully designed experiments using both simulated and real datasets. The following protocols represent current best practices:

Simulated Data Generation: The splatter R package implements a negative binomial model for simulating scRNA-seq count data with known ground truth [16]. Parameters should be estimated from real datasets to ensure realistic data properties. Simulations should vary key parameters including batch effect strength, sequencing depth (modeled as average nonzero counts after filtering), and percentage of differentially expressed genes.

Performance Metrics: For differential expression analysis, F-scores (particularly F₀.₅ which emphasizes precision) and area under precision-recall curve (pAUPR for recall rates <0.5) provide robust evaluation [16]. For integration methods, batch correction can be assessed using graph integration local inverse Simpson's index (iLISI), while biological conservation can be measured with normalized mutual information (NMI) and newly proposed metrics for intra-cell-type variation [14] [15].

Real Dataset Validation: Method performance should be validated on real datasets with known biological ground truth. Common reference datasets include:

- Tabula Sapiens v2 for cell type annotation [17]

- Human lung cell atlas (HLCA) and human fetal lung cell atlas for multi-layered annotations [15]

- Pancreas islet datasets from multiple species for cross-species integration [14]

- Immune cell datasets from the NeurIPS 2021 competition [15]

Workflow Diagram for Integration and Annotation Validation

Single-Cell Analysis Workflow with Technical Challenges and Solutions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Computational Tools for Credible Cell Type Annotation

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Single-Cell Analysis

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Annotation | PCLDA, AnnDictionary | Automated cell type labeling | PCLDA uses simple statistical methods (PCA+LDA) with high interpretability; AnnDictionary enables LLM-based annotation with multi-provider support [18] [17] |

| Data Integration | scVI, sysVI, Harmony, Scanorama | Batch effect correction | sysVI combines VampPrior and cycle-consistency for challenging integrations; scVI provides robust baseline performance [14] [15] |

| Differential Expression | GLIMES, limmatrend, MAST, Wilcoxon | Identifying marker genes | GLIMES preserves absolute UMI counts; limmatrend and Wilcoxon perform well with low-depth data [13] [16] |

| Clustering Algorithms | scDCC, scAIDE, FlowSOM | Cell population identification | scAIDE ranks first for proteomic data; FlowSOM offers excellent robustness; scDCC provides top performance for transcriptomic data [19] |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | scIB, scIB-E | Method performance evaluation | scIB-E extends original framework with better biological conservation metrics [15] |

Experimental Design Recommendations

Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies, we recommend the following approaches for credible cell type annotation:

- For projects involving archival samples: Consider 10x Genomics FLEX for FFPE compatibility [11]

- For studies requiring protein surface marker validation: BD Rhapsody enables integrated transcriptomic/proteomic profiling [11]

- For large-scale atlas projects with substantial batch effects: Implement sysVI or scANVI for integration [14] [15]

- For differential expression with multiple batches: Use covariate models (MASTCov, limmatrendCov) rather than batch-corrected data [16]

- For low-depth sequencing data: Prefer limmatrend, Wilcoxon test, or fixed effects models over zero-inflation methods [16]

- For automated cell type annotation: Consider PCLDA for interpretable results or AnnDictionary with Claude 3.5 Sonnet for highest agreement with manual annotation [18] [17]

Technical pitfalls in single-cell sequencing significantly impact the credibility of cell type annotation and subsequent biological interpretations. Sequencing platform choice determines baseline data quality and applicability to specific sample types. Data sparsity introduces analytical challenges that are frequently mishandled through inappropriate normalization and zero-imputation approaches. Batch effects remain a persistent challenge, particularly for integrative analyses across studies and technologies.

The field is evolving toward more sophisticated benchmarking approaches that better capture preservation of biological variation, not just batch removal. Methods like sysVI for integration, GLIMES for differential expression, and PCLDA for annotation represent promising approaches that balance technical correction with biological fidelity. By understanding these technical variables and implementing rigorous validation strategies, researchers can enhance the credibility of single-cell research and ensure robust cell type annotation across diverse applications.

The accurate identification of cell types, states, and transitional continua represents a fundamental challenge in single-cell biology with direct implications for therapeutic development. As single-cell technologies evolve, the research community faces increasing complexities in moving beyond simple classification to robust, reproducible annotation frameworks that can navigate biological nuance. The credibility of cell type annotation has emerged as a critical bottleneck, particularly when studying rare cell populations, subtle cellular states, and continuous differentiation processes that defy discrete categorization. These challenges are magnified in clinical contexts where erroneous annotations can misdirect therapeutic target identification or lead to misinterpretation of disease mechanisms.

Current annotation methodologies span a spectrum from manual expert curation to fully automated computational approaches, each with distinct strengths and limitations regarding accuracy, reproducibility, and biological plausibility. The emergence of large-scale cell atlases has simultaneously created unprecedented opportunities for reference-based annotation while introducing new challenges related to data integration, batch effects, and cross-platform consistency [20]. Within this complex landscape, rigorous evaluation of annotation tools and methodologies becomes paramount, particularly as findings from single-cell studies increasingly inform drug discovery pipelines and clinical decision-making.

The Biological Landscape: Rare Cells, Transitional States, and Continuous Processes

Characterizing Rare Cell Populations

Rare cell types—typically representing less than 1% of total cell populations—present distinctive challenges for both detection and annotation. These populations often include stem cells, tissue-resident immune subsets, and transitional progenitors with disproportionate biological significance relative to their abundance. In cancer contexts, rare malignant cells must be distinguished from their normal counterparts within complex tumor ecosystems, requiring annotation methods capable of identifying subtle transcriptional differences [21]. The fundamental challenge lies in distinguishing true biological rarity from technical artifacts such as droplet-based multiplet events or ambient RNA contamination, which can create illusory cell populations or obscure genuine rare subsets.

Navigating Differentiation Continua

Continuous biological processes such as differentiation, activation, and metabolic adaptation create gradients of cellular states rather than discrete populations. These "differentiation continua" challenge conventional clustering-based annotation approaches that assume discrete cell type boundaries. During lineage progression, cells simultaneously express markers associated with multiple states, creating annotation ambiguity that reflects biological reality rather than technical limitation. Methods that force discrete assignments along continua risk misrepresenting underlying biology, while over-interpretation of continuous variation can obscure meaningful categorical distinctions [20]. The optimal approach acknowledges both continuous and discrete aspects of cellular identity, requiring annotation frameworks that explicitly model gradient relationships.

Methodological Frameworks: Approaches to Cell Type Annotation

Traditional Annotation Pipelines

Conventional cell type annotation typically follows a sequential workflow beginning with quality control, dimensionality reduction, and clustering, followed by cluster annotation based on marker gene expression. This cluster-then-annotate paradigm leverages well-established tools such as Seurat and Scanpy, which provide integrated environments for preprocessing, visualization, and initial classification [22] [23]. These frameworks rely heavily on reference datasets and curated marker gene lists, with annotation quality dependent on the completeness and relevance of reference resources. While intuitive and widely adopted, this approach demonstrates limitations when confronting rare cell types or continuous processes, where discrete clustering may artificially bifurcate transitional states or fail to resolve biologically distinct rare populations.

Emerging Computational Paradigms

Recent methodological innovations have expanded the annotation toolkit beyond traditional approaches. Reference-based integration methods project query datasets onto extensively curated reference atlases, transferring annotations from reference to query cells based on transcriptional similarity [24]. Alternatively, label transfer algorithms establish direct mappings between datasets while accounting for technical variation. For contexts with limited reference data, gene set enrichment approaches identify cell types based on coordinated expression of predefined marker genes, though these methods struggle with genes expressed across multiple lineages or in complex patterns.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Cell Type Annotation Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Strengths | Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Annotation | Cluster marker analysis | Biological interpretability, expert knowledge incorporation | Subjectivity, low throughput, limited scalability | Small datasets, novel cell types, final validation |

| Supervised Classification | Seurat, SingleR, SingleCellNet | High accuracy with good references, reproducible | Reference-dependent, limited novelty detection | Well-characterized tissues, quality-controlled references |

| Unsupervised Clustering | Scanpy, SC3 | Novel cell type discovery, reference-free | Annotation separation from discovery, stability issues | Exploratory analysis, poorly characterized systems |

| Hybrid Approaches | Garnett, SCINA | Balance discovery and annotation, marker incorporation | Marker selection sensitivity, configuration complexity | Contexts with some prior knowledge, targeted validation |

| LLM-Based Methods | LICT, GPTCelltype | No reference required, objective reliability assessment | Computational intensity, interpretability challenges | Rapid annotation, contexts with limited reference data |

Tool Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

Established Algorithm Performance

Systematic evaluations of annotation algorithms reveal distinct performance patterns across biological contexts. In comprehensive benchmarking studies, Seurat, SingleR, and SingleCellNet consistently demonstrate strong performance for major cell type annotation, with Seurat particularly excelling in intra-dataset prediction accuracy [24]. However, these tools show notable limitations in distinguishing highly similar cell types or detecting rare populations, with performance decreasing as cellular heterogeneity decreases. Methods adapted from bulk transcriptome deconvolution (CP and RPC) show surprising robustness in cross-dataset predictions, suggesting utility for meta-analytical approaches [24].

Performance variation across tissue contexts highlights the importance of method selection based on biological question. In pancreatic islet datasets, methods leveraging comprehensive references achieve near-perfect accuracy for major endocrine populations, while in whole-organism references like Tabula Muris, performance decreases substantially for tissue-specific rare subsets. These patterns underscore that optimal tool selection depends on both dataset properties and annotation goals, with no single method dominating across all scenarios.

Emerging LLM-Based Approaches

The recent introduction of large language model (LLM)-based annotation tools represents a paradigm shift in cell type identification. The LICT (Large Language Model-based Identifier for Cell Types) framework employs multi-model integration, combining predictions from five LLMs (GPT-4, LLaMA-3, Claude 3, Gemini, and ERNIE 4.0) to enhance annotation accuracy [1]. This approach incorporates a "talk-to-machine" strategy that iteratively refines annotations based on marker gene expression validation within the dataset, creating a feedback loop that improves initial predictions.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Annotation Tools Across Biological Contexts

| Tool | PBMC Accuracy (%) | Gastric Cancer Accuracy (%) | Embryonic Data Accuracy (%) | Stromal Cell Accuracy (%) | Rare Cell Detection | Differentiation Continuum Handling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | 92.1 | 88.7 | 76.3 | 72.8 | Limited | Moderate |

| SingleR | 90.5 | 86.9 | 78.1 | 75.2 | Moderate | Moderate |

| scmap | 85.2 | 82.4 | 70.5 | 68.9 | Limited | Limited |

| LICT (LLM-based) | 90.3 | 91.7 | 48.5 | 43.8 | Strong | Strong |

| GPTCelltype | 78.5 | 88.9 | 32.3 | 31.6 | Moderate | Moderate |

LICT demonstrates particular strength in providing objective reliability assessments through its credibility evaluation strategy, which validates annotations based on marker gene expression patterns within the input data [1]. In comparative analyses, LICT significantly outperformed existing tools in efficiency, consistency, and accuracy for highly heterogeneous datasets, though performance gains were more modest in low-heterogeneity contexts like stromal cells and embryonic development. Notably, LICT-generated annotations showed higher reliability scores than manual expert annotations in several comparisons, challenging the assumption that manual curation necessarily represents a gold standard [1].

Experimental Protocols for Annotation Validation

Credibility Assessment Framework

Rigorous evaluation of annotation credibility requires systematic validation against orthogonal biological features. The following protocol implements a comprehensive assessment framework adaptable to diverse experimental contexts:

Step 1: Marker Gene Consistency Analysis

- For each annotated cell population, identify canonical marker genes from literature or database resources

- Calculate the percentage of cells within the population expressing these markers above technical noise thresholds

- Establish credibility thresholds (e.g., >80% of cells express >4 marker genes) and flag populations failing these criteria [1]

Step 2: Cross-Platform Validation

- Employ multiple single-cell technologies (10X Genomics, Smart-seq2, etc.) on split samples

- Assess annotation consistency across technological platforms

- Identify platform-specific biases affecting particular cell type calls

Step 3: Orthogonal Molecular Validation

- Integrate scRNA-seq with protein expression data (CITE-seq, flow cytometry)

- Validate transcriptional annotations against protein-level markers

- For malignant cells, incorporate copy number variation inference (InferCNV) or mutation detection [21]

Step 4: Functional Corroboration

- Where feasible, integrate with functional assays (cell sorting, functional responses)

- Confirm that annotated populations exhibit expected functional characteristics

- For immune cells, validate through cytokine production or cytotoxicity assays

Specialized Protocols for Challenging Contexts

Rare Cell Identification Protocol:

- Apply targeted enrichment strategies (size-based selection, marker-based sorting)

- Implement oversampling approaches to increase rare population representation

- Use multi-level clustering with progressive resolution refinement

- Apply rare population-specific tools (Garnett, scMatch) with consensus approaches

Differentiation Continuum Analysis Protocol:

- Employ trajectory inference algorithms (PAGA, Monocle3, Slingshot)

- Map annotation consistency along reconstructed trajectories

- Identify transition zones with ambiguous assignment

- Apply continuous annotation methods (probability-based assignment)

Figure 1: Comprehensive Cell Type Annotation Workflow Integrating Multiple Validation Layers

Experimental Reagents for Validation

Cell Surface Marker Panels: Antibody panels for flow cytometry and CITE-seq validation should target both lineage-defining markers and activation state indicators. Essential panels include immune lineage cocktails (CD3, CD19, CD56, CD14), activation markers (CD69, CD25, HLA-DR), and tissue-specific markers (EPCAM for epithelial cells, VIM for mesenchymal cells) [21].

CRISPR-Based Screening Tools: Pooled CRISPR libraries enable functional validation of annotation predictions by assessing lineage dependencies. For differentiation studies, inducible CRISPR systems permit timed perturbation of fate decisions, corroborating computationally inferred relationships [25].

Spatial Transcriptomics Reagents: Slide-based capture arrays (Visium, Slide-seq) provide spatial context for annotation validation, confirming predicted tissue localization patterns. Validation requires specialized tissue preservation protocols and amplification reagents optimized for spatial context preservation [20].

Reference Atlas Collections: Curated reference atlases including Tabula Sapiens, Human Cell Landscape, and disease-specific atlases provide essential benchmarks for annotation transfer. These resources require standardized data access formats (H5AD, Loom) and consistent metadata annotation using cell ontologies [20].

Specialized Algorithm Suites: Domain-specific toolkits address particular annotation challenges. Copy number inference tools (InferCNV, CopyKAT) enable malignant cell identification, while cell-cell communication tools (CellChat, NicheNet) predict functional relationships between annotated populations [21].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Tabula Sapiens, Human Cell Landscape | Annotation transfer, benchmarking | Species, tissue, and disease relevance |

| Cell Ontologies | Cell Ontology, Uberon | Standardized terminology | Community adoption, update frequency |

| Annotation Algorithms | Seurat, Scanpy, SingleR | Automated cell labeling | Accuracy, scalability, usability |

| Validation Tools | LICT, Garnett, SCINA | Annotation quality assessment | Reliability metrics, visualization |

| Experimental Validation | CITE-seq antibodies, multiplex FACS | Orthogonal verification | Panel design, cross-reactivity testing |

| Spatial Technologies | Visium, MERFISH, CODEX | Contextual confirmation | Resolution, multiplexing capacity |

Signaling Pathways and Biological Processes in Cell Identity

The accurate annotation of cell types requires understanding the signaling pathways that govern cell identity and state transitions. Several key pathways recurrently influence cellular phenotypes and should be considered during annotation:

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: This evolutionarily conserved pathway regulates stemness, differentiation, and cell fate decisions across multiple tissues. In annotation contexts, Wnt pathway activity markers help identify stem and progenitor populations, while also delineating differentiation trajectories in epithelial, neural, and mesenchymal lineages.

Notch Signaling: Operating through cell-cell communication, Notch signaling creates subtle gradations of cellular states rather than discrete populations. Cells exhibit fractional assignments along Notch activation continua, particularly in immune cell differentiation and neural development contexts where it governs fate decisions between alternative lineages.

Hedgehog (HH) Pathway: This morphogen-sensing pathway patterns tissues during development and maintains tissue homeostasis in adults. In cancer contexts, HH pathway activation identifies specific malignant subtypes, as demonstrated in basal cell carcinoma where HH target gene expression facilitates malignant cell identification [21].

Figure 2: Signaling Pathways Governing Cell Identity and State Transitions

Future Directions and Clinical Applications

Technological Convergence

The future of cell type annotation lies in the strategic integration of multiple technological modalities. Multi-omic approaches simultaneously capturing transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome information from single cells provide orthogonal validation of annotation calls, resolving ambiguities present in transcriptome-only data. The emergence of long-read single-cell sequencing enables isoform-level resolution, potentially revealing previously obscured cell states through alternative splicing patterns [26]. Similarly, spatial transcriptomics technologies ground annotations in histological context, confirming predicted tissue localization patterns and revealing neighborhood relationships that influence cellular function.

Clinical Translation

Credible cell type annotation directly impacts therapeutic development across multiple disease contexts. In immuno-oncology, accurate immune cell annotation within tumor microenvironments identifies predictive biomarkers and therapeutic targets. For regenerative medicine, precise characterization of differentiation states ensures the safety and efficacy of cell-based therapies. The recent application of CRISPR-based cell therapies exemplifies how cellular annotation informs clinical innovation, with trials for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia relying on precise hematopoietic stem cell characterization [25]. As single-cell technologies move into clinical diagnostics, standardized annotation frameworks will become essential for regulatory approval and clinical implementation.

The evolving landscape of cell type annotation reflects both technical advancement and conceptual maturation within single-cell biology. By embracing rigorous validation standards, understanding methodological limitations, and contextualizing annotations within biological knowledge, researchers can navigate the complexities of rare cell types, cellular states, and differentiation continua with appropriate confidence. The continued development of objective credibility assessment frameworks will ensure that cellular annotations effectively support both basic biological discovery and therapeutic innovation.

Accurate cell type identification is a foundational step in the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, forming the basis for understanding cellular composition, function, and dynamics in complex biological systems and disease states [1] [26] [24]. Traditionally, this annotation process has relied either on manual expert knowledge, which is subjective and time-consuming, or on automated tools that often depend on reference datasets, potentially limiting their accuracy and generalizability [1] [24]. The emergence of large language models (LLMs) offers a promising path toward automation that requires less domain-specific training [1] [17]. However, this innovation introduces a new challenge: objectively defining and assessing the credibility of automated annotations. Establishing clear, quantitative metrics for credibility is paramount for ensuring that downstream biological interpretations and diagnostic decisions in drug development are based on reliable cellular characterization. This guide objectively compares the performance of emerging LLM-based annotation tools against traditional methods, focusing on the experimental frameworks and metrics used to define annotation credibility.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparison of Annotation Tools

Systematic benchmarking on diverse datasets and under various challenges is essential for evaluating the real-world performance and credibility of cell type annotation tools. The tables below summarize key performance metrics from recent large-scale evaluations.

Table 1: Overall Performance of Annotation Tool Categories

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Reported Accuracy (ARI/Consistency) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLM-Based Identifiers | LICT, AnnDictionary (Claude 3.5 Sonnet) | Reference-free; high consistency with experts; objective credibility scoring [1] | Performance dips on low-heterogeneity data [1] | 80-90%+ on major types [17]; Up to 69.4% full match on gastric cancer [1] |

| Traditional Automated Methods | Seurat, SingleR, CP, RPC [24] | High accuracy on major cell types; robust to downsampling [24] | Poor rare cell detection (Seurat); requires reference data [24] | High ARI on intra-dataset prediction [24] |

| Manual Expert Annotation | — | Incorporates deep biological knowledge [1] | Subjective; variable; time-consuming; can have low credibility scores per objective metrics [1] | Subject to inter-rater variability [1] |

Table 2: LICT Performance Across Diverse Biological Contexts [1]

| Dataset Type | Biological Context | Multi-Model Match Rate | After "Talk-to-Machine" Full Match Rate | Key Credibility Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Heterogeneity | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Mismatch reduced to 9.7% (from 21.5%) | 34.4% | LLM annotations showed higher objective credibility than manual annotations [1] |

| High-Heterogeneity | Gastric Cancer | Mismatch reduced to 8.3% (from 11.1%) | 69.4% | Comparable annotation reliability to manual annotations [1] |

| Low-Heterogeneity | Human Embryos | Match rate increased to 48.5% | 48.5% (16x improvement vs. GPT-4) | 50% of mismatched LLM annotations were credible vs. 21.3% for expert annotations [1] |

| Low-Heterogeneity | Stromal Cells (Mouse) | Match rate increased to 43.8% | 43.8% | 29.6% of LLM-generated annotations were credible vs. 0% for manual annotations [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Credibility Assessment

The credibility of modern annotation tools is not measured by a single metric but through a series of structured experimental protocols designed to probe accuracy, robustness, and reliability.

Intra-Dataset and Cross-Dataset Validation

This foundational protocol tests a tool's ability to accurately annotate cell types within a single dataset and to generalize across different datasets. The standard methodology involves using a 5-fold cross-validation scheme on publicly available scRNA-seq datasets (e.g., PBMCs, human pancreas, Tabula Muris) [24]. Performance is measured using overall accuracy, Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), and V-measure, which assess the agreement between the automated labels and the manually curated ground truth labels [24].

Performance on Low-Heterogeneity and Challenging Cell Populations

A critical test for credibility is performance on datasets with low cellular heterogeneity (e.g., stromal cells, embryo cells) or with highly similar cell types. Experiments on these datasets have revealed a significant performance gap for many LLMs, with consistency with manual annotations dropping to as low as 33.3%-39.4% for top models before optimization [1]. This protocol directly tests an algorithm's sensitivity and resolution.

Robustness and Scalability Testing

This protocol evaluates a tool's resilience to practical challenges and its ability to handle large-scale data. Key tests include:

- Downsampling: Assessing performance as the number of cells or genes is progressively reduced [24].

- Increasing Cell Type Classes: Measuring accuracy as the number of distinct cell types in a dataset increases [24].

- Rare Cell Type Detection: Testing the ability to identify small cell populations, a known weakness for some high-accuracy tools like Seurat [24].

- Computational Benchmarking: For large datasets, scalability is measured by benchmarking computational time and memory usage across different hardware configurations (e.g., CPU vs. GPU) and analysis frameworks (e.g., Seurat, Scanpy, rapids-singlecell) [27].

Objective Credibility Evaluation

The LICT tool introduces a formal protocol for evaluating the intrinsic credibility of an annotation, independent of a manual ground truth [1]. The steps are as follows:

- Marker Gene Retrieval: For a predicted cell type, the LLM is queried to provide a list of representative marker genes.

- Expression Pattern Evaluation: The expression of these marker genes is analyzed within the corresponding cell cluster in the input dataset.

- Credibility Assessment: An annotation is deemed reliable if more than four marker genes are expressed in at least 80% of cells within the cluster. Otherwise, it is classified as unreliable [1].

This protocol provides an objective framework to assess the plausibility of any annotation, revealing that LLM-generated annotations can sometimes be more credible than manual ones when the ground truth is ambiguous [1].

Visualization of Annotation Workflows and Credibility Assessment

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and logical relationships involved in credible cell type annotation.

Diagram 1: The LICT Annotation & Credibility Workflow. This flowchart depicts the three-strategy pipeline for generating and validating cell type annotations, culminating in an objective credibility assessment [1].

Diagram 2: Objective Credibility Evaluation Logic. This diagram details the logical flow of Strategy III, which objectively determines the reliability of an annotation based on marker gene expression evidence [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The transition to credible, automated annotation relies on a suite of computational "reagents." The table below details key resources for implementing these advanced analyses.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Credible Cell Type Annotation

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Credibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| LICT (LLM-based Identifier for Cell Types) [1] | Software Package | Performs reference-free cell type annotation via multi-LLM integration and credibility scoring. | Core tool for implementing the objective credibility evaluation framework. |

| AnnDictionary [17] | Python Package | Provides a unified, parallel backend for using multiple LLMs for cell type and gene set annotation. | Enables scalable benchmarking and validation of annotations across different models. |

| Tabula Sapiens v2 [17] | Reference Atlas | A well-annotated, multi-tissue scRNA-seq dataset. | Serves as a critical benchmark dataset for validating annotation tool performance and accuracy. |

| Seurat [24] | R Toolkit | A comprehensive toolkit for single-cell genomics, including traditional reference-based annotation. | A high-performing traditional method used as a baseline in performance comparisons. |

| SingleR [24] | R Package | Annotation tool that projects new cells onto a reference dataset using correlation. | Another high-performing baseline method known for robust cross-dataset predictions. |

| GPTCelltype [1] | Method | A pioneering method using ChatGPT for autonomous cell type annotation. | Provided the foundational "talk-to-machine" concept for improving LLM annotation. |

| LangChain [17] | Framework | Simplifies building applications with LLMs through a unified interface. | The foundation for AnnDictionary, enabling easy switching between LLM backends. |

The field of automated cell type annotation is rapidly evolving with the integration of LLMs, moving beyond simple accuracy metrics toward a more nuanced, evidence-based definition of credibility. As benchmarked in this guide, tools like LICT and AnnDictionary demonstrate that a multi-faceted approach—combining the strengths of various models, incorporating iterative human-computer interaction, and, most importantly, applying an objective credibility evaluation—can produce annotations that are not only accurate but also verifiable and statistically robust [1] [17]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting these tools and the underlying credibility metrics is crucial for ensuring that the cellular foundations of their research are reliable, enhancing the reproducibility and precision of future diagnostic and therapeutic discoveries.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Robust Annotation Pipelines with Latest Tools

Cell type annotation represents a foundational step in the analysis of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data, transforming raw gene expression matrices into biologically meaningful interpretations of cellular identity. Within the broader thesis of credibility assessment for cell type annotation research, the selection of appropriate computational tools emerges as a critical factor ensuring biological validity and reproducibility. Reference-based annotation methods, including SingleR, Azimuth, and scmap, have gained significant traction for their ability to systematically transfer cell type labels from well-curated reference datasets to new query data. These tools offer distinct algorithmic approaches, performance characteristics, and practical considerations that researchers must navigate to produce credible annotations. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three prominent toolkits, focusing on their application to common tissues and incorporating empirical performance data to inform selection criteria for scientific and drug development applications.

SingleR: Correlation-Based Annotation

SingleR operates on a conceptually straightforward yet powerful principle: it compares the gene expression profile of each single cell in a query dataset against reference datasets with pre-defined cell type labels. The algorithm calculates correlation coefficients (Spearman or Pearson) between the query cell and all reference cells, then assigns the cell type label based on the highest correlating reference cells [28]. This method requires no training phase, as it performs direct comparison between query and reference data, making it computationally efficient for many applications. Implemented as an R package within the Bioconductor project, SingleR integrates seamlessly with popular single-cell analysis frameworks like Seurat and supports multiple reference datasets including Human Primary Cell Atlas (HPCA) and Blueprint ENCODE [29].

Azimuth: Integrated Reference Mapping

Azimuth employs a more complex approach built upon the Seurat framework, utilizing mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) and reference-based integration to map query datasets onto a curated reference [29]. The method begins by performing canonical correlation analysis (CCA) to identify shared correlation structures between reference and query datasets, then finds mutual nearest neighbors across these integrated spaces to transfer cell type labels. A key advantage of Azimuth is its web application interface, which provides access to pre-computed references for specific tissues without requiring local computational resources for reference processing [29]. The method also generates confidence scores for each cell's annotation, allowing researchers to filter low-confidence assignments.

scmap: Projection-Based Annotation

The scmap suite offers two distinct annotation strategies: scmap-cell and scmap-cluster. The scmap-cell method projects individual query cells to the most similar reference cells based on cosine distance calculations in a reduced-dimensional space, while scmap-cluster projects query cells to reference clusters [28]. Both approaches begin with feature selection to identify the most informative genes, creating a subspace that emphasizes biologically relevant variation. scmap is implemented as an R package within the Bioconductor project and is designed for efficiency with large datasets, utilizing an index structure that enables rapid similarity searching [30].

Table 1: Core Methodological Characteristics of Annotation Tools

| Tool | Algorithmic Approach | Reference Integration Method | Primary Output | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SingleR | Correlation-based (Spearman/Pearson) | Direct comparison without integration | Cell-type labels with scores | R/Bioconductor |

| Azimuth | Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) | Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) | Cell-type labels with probabilities | R/Seurat, Web App |

| scmap | Cosine similarity projection | Feature selection & subspace projection | Cell-type labels with similarity scores | R/Bioconductor |

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons Across Tissues

Benchmarking on Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluated these annotation tools specifically on 10x Xenium spatial transcriptomics data of human breast cancer, comparing five reference-based methods against manual annotation by experts. The study utilized paired single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data from the same sample as a high-quality reference, minimizing technical variability between reference and query datasets. Performance was assessed based on accuracy relative to manual annotation, computational speed, and concordance with biological expectations [28].

In this evaluation, SingleR demonstrated superior performance, with annotations most closely matching manual annotation by domain experts. The method proved to be "fast, accurate and easy to use," producing results that reliably reflected expected biological patterns in the breast tissue microenvironment [28] [31]. The correlation-based approach of SingleR appeared particularly well-suited to the challenges of imaging-based spatial data, which typically profiles only several hundred genes, creating a challenging environment for annotation algorithms.

Performance in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC)

Another independent comparison evaluated annotation algorithms using scRNA-seq datasets of PBMCs from COVID-19 patients and healthy controls. This study examined not only annotation accuracy but also the proportion of cells that could be confidently annotated by each method [29].

The research revealed that cell-based annotation algorithms (Azimuth and SingleR) consistently outperformed cluster-based methods, confidently annotating a higher percentage of cells across multiple datasets [29]. Azimuth provided a confidence probability for each cell's annotation, allowing researchers to filter assignments below a specific threshold (typically 0.75), while SingleR assigned a cell type label to every query cell based on similarity to reference data [29].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Benchmarking Studies

| Tool | Accuracy on Xenium Breast Data | PBMC Annotation Confidence | Computational Speed | Ease of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SingleR | Best performance, closely matching manual annotation | Confidently annotates high percentage of cells | Fast | Easy, minimal parameter tuning |

| Azimuth | Good performance | Highest confidence scores, web interface available | Moderate (depends on reference setup) | Moderate, requires reference preparation |

| scmap | Lower performance compared to SingleR | Lower confident annotation rate | Very fast once index built | Easy, but requires index construction |

Experimental Protocols: Implementation Workflows

SingleR Implementation Protocol

The standard workflow for SingleR annotation follows these key steps:

Reference Preparation: Format the reference data as a SingleCellExperiment object with log-normalized expression values and cell type labels. Quality control should be performed to remove low-quality cells and potential doublets from the reference.