Evaluating Zero-Shot Single-Cell Foundation Model Embeddings: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Single-cell Foundation Models (scFMs) promise to revolutionize biological discovery by providing powerful, pre-trained representations of single-cell RNA sequencing data.

Evaluating Zero-Shot Single-Cell Foundation Model Embeddings: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

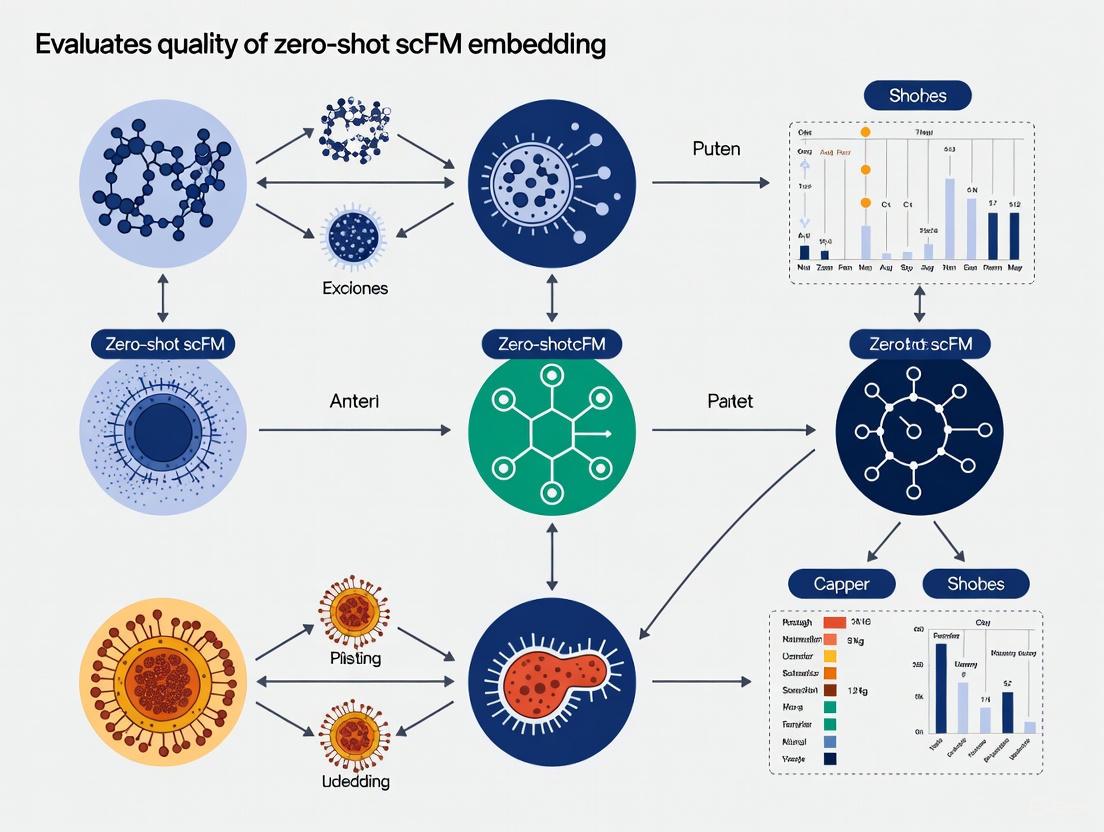

Single-cell Foundation Models (scFMs) promise to revolutionize biological discovery by providing powerful, pre-trained representations of single-cell RNA sequencing data. However, their real-world utility, particularly in zero-shot settings where no task-specific fine-tuning is possible, remains a critical and debated topic. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate the quality of zero-shot scFM embeddings. We synthesize the latest benchmarking studies to explore the foundational principles of zero-shot evaluation, detail methodological approaches for applying these embeddings to key tasks like cell type annotation and batch integration, offer troubleshooting strategies for overcoming common performance limitations, and present a rigorous framework for the comparative validation of different models against established baselines. Our goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively leverage scFMs for exploratory biological research and clinical translation.

The Promise and Reality of Zero-Shot Learning in Single-Cell Biology

Zero-shot evaluation, the process of assessing a foundation model's performance on downstream tasks without any task-specific fine-tuning, has emerged as a critical methodology for validating the true biological understanding and utility of single-cell foundation models (scFMs). In exploratory research settings where predefined labels are absent and biological composition is unknown, the ability to leverage pretrained knowledge zero-shot is paramount. Recent benchmarking studies reveal that while scFMs show promise, their zero-shot performance often fails to consistently outperform simpler, established methods across key tasks like cell type annotation and batch integration. This guide provides an objective comparison of current scFM performance, details essential experimental protocols for rigorous evaluation, and equips researchers with the tools needed to critically assess embedding quality for their exploratory biological research.

In single-cell biology, many research scenarios are fundamentally exploratory, where researchers aim to discover novel cell states, identify rare populations, or characterize previously unannotated tissues. In these contexts, predefined classification labels are unavailable, making supervised fine-tuning of specialized models impossible. Zero-shot evaluation directly addresses this challenge by testing whether models have acquired a general, transferable understanding of biology during pretraining that can be applied to novel datasets and problems without additional training [1].

The significance of this evaluation paradigm is profound. It moves beyond simply measuring performance on standardized benchmarks to assessing whether foundation models can genuinely accelerate discovery in realistic research settings. As noted in recent critical assessments, "Understanding the performance of models in zero-shot settings is critical to applications that exclude the ability to fine-tune, such as discovery settings where labels are unknown" [2] [1]. This makes zero-shot evaluation not merely an academic exercise, but an essential validation step for deploying scFMs in practical research workflows, particularly in drug development and clinical applications where biological ground truth may be partially unknown.

Comparative Performance of Single-Cell Foundation Models

Zero-Shot Capabilities Across Biological Tasks

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have evaluated multiple scFMs against traditional baselines using standardized metrics. The performance landscape reveals significant variation across models and tasks, with no single model consistently dominating across all applications. The following table summarizes key findings from large-scale benchmarks evaluating six prominent scFMs (Geneformer, scGPT, UCE, scFoundation, LangCell, and scCello) against established baselines like Highly Variable Genes (HVG), Seurat, Harmony, and scVI [3].

Table 1: Zero-Shot Performance Comparison Across Cell-Level Tasks

| Model | Cell Type Annotation (AvgBIO Score) | Batch Integration (iLISI Score) | Cancer Cell Identification (F1 Score) | Drug Sensitivity Prediction (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.42 |

| Geneformer | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.38 |

| scFoundation | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.45 |

| HVG Baseline | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.47 |

| Harmony Baseline | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.43 |

| scVI Baseline | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.46 |

Recent focused evaluations specifically testing scGPT and Geneformer in zero-shot settings found that "both models perform worse than selecting highly variable genes (HVG) and using more established methods such as Harmony and scVI in cell type clustering, as measured by average BIO (AvgBio) score" [1]. This underperformance relative to simpler methods raises important questions about the current state of foundation models in single-cell biology.

Performance in Perturbation Prediction

Prediction of cellular responses to genetic perturbations represents a particularly challenging task that tests models' causal understanding of biology. A recent benchmark termed PertEval-scFM systematically evaluated scFMs for perturbation effect prediction against deliberately simple baselines [4]. The results were striking: "Our results show that scFM embeddings offer limited improvement over simple baseline models in the zero-shot setting, particularly under distribution shift" [4].

Table 2: Perturbation Effect Prediction Performance (L2 Distance)

| Model | Double Perturbation Prediction | Unseen Perturbation Generalization | Genetic Interaction Detection (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.61 |

| scFoundation | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.65 |

| Geneformer* | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.58 |

| Additive Baseline | 0.82 | 0.85 | N/A |

| No Change Baseline | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.59 |

*Note: Models marked with * were repurposed with linear decoders as they weren't specifically designed for this task [5]. The L2 distance metric measures the difference between predicted and observed expression values, with lower values indicating better performance.

Perhaps most notably, a comprehensive study published in Nature Methods concluded that "deep-learning-based gene perturbation effect prediction does not yet outperform simple linear baselines" [5]. This finding challenges claims that scFMs have internalized sufficient biological knowledge to accurately predict outcomes of novel experiments.

Experimental Protocols for Zero-Shot Evaluation

Standardized Evaluation Framework

Rigorous zero-shot evaluation requires standardized protocols to ensure fair comparison across models. The BioLLM framework has emerged as a valuable tool for this purpose, providing "standardized APIs and comprehensive documentation" along with support for "zero-shot and fine-tuning support for benchmarking tasks" [6]. The typical evaluation workflow involves several critical stages, as illustrated below:

Key Evaluation Metrics and Methodologies

Benchmarking studies employ multiple metrics to evaluate different aspects of model performance. A comprehensive benchmark evaluating six scFMs against established baselines utilized "12 metrics spanning unsupervised, supervised, and knowledge-based approaches" [3]. Key methodologies include:

Cell Type Annotation: Evaluated using metrics like Average BIO Score (AvgBIO) and Average Silhouette Width (ASW) to measure clustering quality and separation of known cell types without using label information during embedding generation [3] [1].

Batch Integration: Assessed using batch mixing scores (iLISI) and principal component regression (PCR) to quantify the removal of technical artifacts while preserving biological variation [1]. Studies have found that "Geneformer's embeddings across all datasets show a higher proportion of variance explained by batch effects compared to the original data, indicating inadequate batch mixing" [1].

Biological Consistency: Novel metrics like scGraph-OntoRWR measure "the consistency of cell type relationships captured by scFMs with prior biological knowledge" by leveraging cell ontology information [3].

Perturbation Prediction: Evaluated using L2 distance between predicted and observed expression values, Pearson delta correlation, and genetic interaction detection capability [5].

The evaluation typically follows a zero-shot protocol where "the pretrained zero-shot scFM embeddings indeed capture biological insights into the relational structure of genes and cells" are extracted without any fine-tuning and directly used for downstream tasks [3].

Implementing rigorous zero-shot evaluation requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details key solutions available to researchers:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Zero-Shot Evaluation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioLLM Framework | Unified interface for scFM evaluation | Standardized APIs, model switching, consistent benchmarking | Open Source [6] |

| PertEval-scFM | Specialized perturbation prediction benchmark | Standardized framework, multiple baseline comparisons | GitHub [4] |

| CELLxGENE Census | Curated single-cell data repository | High-quality datasets, standardized processing | Registry [3] [7] |

| scGraph-OntoRWR | Biological consistency metric | Cell ontology-informed evaluation | Implementation Code [3] |

| AIDA v2 Dataset | Independent evaluation dataset | Asian immune diversity, unbiased validation | CellxGene [3] |

These resources collectively enable researchers to implement comprehensive zero-shot evaluation protocols, leveraging standardized metrics and datasets to ensure comparable results across different studies and models.

Interpretation of Zero-Shot Evaluation Results

Current Limitations and Challenges

The consistent underperformance of scFMs relative to simpler baselines in zero-shot settings points to fundamental challenges in current approaches. The masked language model pretraining framework used by many scFMs may not be optimally suited for learning biologically meaningful representations that transfer zero-shot to diverse tasks [1]. Additionally, there appears to be "an unclear relationship between the pretraining objective and cell type clustering" [1], suggesting that current pretraining tasks may not adequately capture the biological knowledge needed for exploratory research.

The performance variability across different dataset types and tissue contexts further complicates model selection. As noted in benchmarks, "no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, emphasizing the need for tailored model selection based on factors such as dataset size, task complexity, biological interpretability, and computational resources" [3].

Pathways for Improvement

Recent research suggests several promising directions for improving zero-shot capabilities in scFMs. The introduction of biological knowledge through metrics like LCAD (Lowest Common Ancestor Distance), which "measures the ontological proximity between misclassified cell types," provides a more nuanced evaluation framework [3]. Additionally, multimodal approaches that integrate transcriptomic data with textual annotations, such as CellWhisperer, show potential for enhancing model interpretability and biological grounding [7].

The relationship between pretraining data composition and zero-shot performance also merits further investigation. Evidence suggests that while pretraining provides clear benefits over randomly initialized models, "beyond a certain limit, larger and more diverse datasets may no longer confer additional benefits" [1]. More targeted pretraining strategies focusing on data quality rather than quantity may yield better zero-shot performance.

Zero-shot evaluation represents an essential methodology for assessing the true capabilities of single-cell foundation models in biologically realistic, exploratory research scenarios. Current evidence demonstrates that while scFMs show promising performance across various tasks, their zero-shot capabilities often fail to exceed simpler, established methods. This underscores the importance of rigorous benchmarking using standardized protocols before deploying these models in critical research applications, particularly in drug development and clinical settings where biological discovery is the primary goal. As the field advances, continued focus on biologically meaningful evaluation metrics and specialized model architectures will be essential for developing foundation models that genuinely enhance our ability to explore and understand cellular biology.

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) represent a revolutionary approach in computational biology, applying the transformer architecture—previously successful in natural language processing—to single-cell transcriptomics data [8]. These models are pretrained on millions of single cells, treating each cell as a "sentence" and genes as "words" to learn fundamental biological principles that can be generalized across diverse downstream tasks [9]. The promise of scFMs lies in their potential to overcome the significant challenges of single-cell RNA sequencing data, including high sparsity, high dimensionality, and low signal-to-noise ratio [3]. By leveraging self-supervised learning on massive datasets, scFMs aim to capture universal biological knowledge during pretraining, endowing them with emergent abilities for zero-shot learning and efficient adaptation to various applications without task-specific training [3].

The evaluation of zero-shot scFM embedding quality has become a critical research focus, as this capability is particularly valuable for exploratory biological research where labeled data may be scarce or unavailable [1]. Unlike fine-tuned applications where models are further trained on specific tasks, zero-shot evaluation tests the model's inherent biological understanding captured during pretraining, providing insights into the true knowledge representation capacity of these foundation models [1]. This overview examines the current scFM landscape, focusing on performance comparisons, methodological approaches, and practical considerations for researchers seeking to leverage these tools in biological and clinical investigations.

Model Architectures & Technical Approaches

Single-cell foundation models share a common conceptual foundation but diverge significantly in their architectural implementations and technical strategies. Most scFMs utilize transformer-based architectures, but with variations tailored to the unique characteristics of single-cell data [8]. The fundamental challenge these models address is the non-sequential nature of gene expression data—unlike words in a sentence, genes lack inherent ordering, requiring innovative tokenization and positional encoding strategies [8] [9].

Tokenization Strategies

Tokenization converts raw gene expression data into discrete units processable by transformer models. A common approach ranks genes within each cell by expression levels, treating the ordered list of top genes as the input sequence [8] [9]. Alternative methods include binning genes by expression values or using normalized counts directly [9]. Gene identifiers are typically represented through embedding layers, while expression values may be handled through value embeddings, value binning, or value projection approaches [3]. Special tokens may be added to represent cell identity, metadata, or multimodal information, enriching the contextual understanding of each cell [9].

Architectural Variations

The transformer architectures employed by scFMs generally fall into three categories: encoder-based, decoder-based, and encoder-decoder designs [8]. Encoder-based models like Geneformer use bidirectional attention mechanisms that consider all genes simultaneously, making them well-suited for classification and embedding tasks [3] [8]. Decoder-based models like scGPT employ unidirectional masked self-attention, iteratively predicting masked genes conditioned on known genes, which aligns well with generative tasks [8]. Hybrid encoder-decoder architectures attempt to balance both capabilities [3]. Currently, no single architecture has emerged as definitively superior, with each demonstrating strengths in different applications [8].

Table 1: Architectural Comparison of Prominent Single-Cell Foundation Models

| Model | Architecture Type | Parameters | Pretraining Dataset Size | Input Genes | Output Dimension | Value Embedding | Positional Embedding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer | Encoder | 40M | 30M cells | 2048 ranked genes | 256/512 | Ordering | ✓ |

| scGPT | Decoder | 50M | 33M cells | 1200 HVGs | 512 | Value binning | × |

| scFoundation | Encoder-Decoder | 100M | 50M cells | 19,264 genes | 3072 | Value projection | × |

| UCE | Encoder | 650M | 36M cells | 1024 sampled genes | 1280 | / | ✓ |

Pretraining Objectives

Most scFMs employ masked gene modeling (MGM) as their primary pretraining objective, where random subsets of genes are masked and the model must predict them based on remaining context [3] [8]. However, implementations vary—Geneformer uses categorical cross-entropy loss for gene identity prediction, scGPT employs mean squared error loss for expression value prediction, while UCE utilizes binary cross-entropy to predict whether genes are expressed [3]. These differing objectives shape what knowledge each model captures during pretraining and influences their performance across downstream tasks.

Diagram 1: Generalized Architecture of Single-Cell Foundation Models

Comprehensive Performance Benchmarking

Rigorous benchmarking studies have provided critical insights into the practical performance of scFMs across diverse biological tasks. A comprehensive 2025 benchmark evaluated six scFMs against established baselines using 12 metrics spanning unsupervised, supervised, and knowledge-based approaches [3]. The evaluation encompassed two gene-level and four cell-level tasks across datasets with diverse biological conditions, including clinically relevant applications across seven cancer types and four drugs [3].

Zero-Shot Embedding Quality

Zero-shot evaluation, which assesses model performance without task-specific fine-tuning, has revealed significant limitations in current scFMs. Studies demonstrate that in zero-shot settings, popular models like Geneformer and scGPT frequently underperform simpler methods such as Highly Variable Genes (HVG) selection and established integration tools like Harmony and scVI for cell type clustering [1]. Quantitative analysis shows that both Geneformer and scGPT produce cell embeddings with poorer separation of known cell types compared to these baselines across multiple datasets, as measured by average BIO (AvgBio) score and average silhouette width (ASW) metrics [1].

Table 2: Zero-Shot Performance Comparison Across Cell Type Clustering Tasks

| Model | Pancreas Dataset (AvgBIO) | PBMC Dataset (AvgBIO) | Immune Dataset (AvgBIO) | Tabula Sapiens (AvgBIO) | Overall Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVG Selection | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 1 |

| scVI | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 2 |

| Harmony | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 3 |

| scGPT | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 4 |

| Geneformer | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 5 |

Batch Integration Capabilities

Batch integration, which aims to remove technical artifacts while preserving biological variation, presents another challenge for scFMs. Qualitative assessment of the Pancreas benchmark dataset reveals that while Geneformer and scGPT can integrate data from experiments using the same technology, they generally fail to correct for batch effects between different techniques [1]. Geneformer's embeddings particularly struggle, often showing clustering primarily driven by batch effects rather than biological meaningfulness [1]. Quantitative evaluation with batch integration metrics confirms that Geneformer consistently underperforms relative to scGPT, Harmony, scVI, and HVG across most datasets [1].

Perturbation Prediction Performance

Perhaps the most striking benchmark results come from perturbation prediction tasks, where scFMs are evaluated on their ability to predict transcriptome changes after genetic perturbations. A 2025 study in Nature Methods compared five foundation models and two other deep learning models against deliberately simple baselines for predicting effects of single or double gene perturbations [5]. Surprisingly, none of the complex models outperformed simple additive baselines that predict the sum of individual logarithmic fold changes [5]. Furthermore, in predicting genetic interactions—where the phenotype of simultaneous perturbations differs from additive expectations—no model performed better than the "no change" baseline that always predicts control condition expression [5].

Experimental Protocols & Evaluation Methodologies

Robust evaluation of scFMs requires standardized protocols that reflect real-world biological applications. Benchmarking studies have developed sophisticated methodologies to assess model capabilities across diverse tasks and datasets.

Benchmarking Framework Design

The most comprehensive benchmarks employ a multi-faceted approach evaluating both gene-level and cell-level tasks under realistic conditions [3]. Gene-level tasks typically focus on gene function prediction and gene-gene relationship inference, while cell-level tasks include batch integration, cell type annotation, cancer cell identification, and drug sensitivity prediction [3]. To ensure biological relevance, benchmarks incorporate large and diverse datasets with high-quality labels and introduce independent, unbiased validation datasets like the Asian Immune Diversity Atlas (AIDA) v2 from CellxGene to mitigate data leakage concerns [3].

Novel Evaluation Metrics

Beyond standard performance metrics, researchers have developed innovative evaluation approaches specifically designed to assess the biological relevance of scFM embeddings. The scGraph-OntoRWR metric measures the consistency of cell type relationships captured by scFMs with prior biological knowledge encoded in cell ontologies [3]. Similarly, the Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD) metric assesses the ontological proximity between misclassified cell types, providing a biologically-informed measure of annotation error severity [3]. The Roughness Index (ROGI) quantitatively estimates how model performance correlates with cell-property landscape roughness in the pretrained latent space, verifying that performance improvements arise from smoother landscapes that reduce training difficulty for task-specific models [3].

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Evaluation Framework for scFM Benchmarking

Zero-Shot Evaluation Protocol

Zero-shot evaluation follows a specific protocol where pretrained model embeddings are used directly without any task-specific fine-tuning [1]. For cell type clustering tasks, embeddings are extracted and evaluated using clustering metrics like average silhouette width and BIO scores [1]. For batch integration, metrics assess both batch mixing effectiveness and biological conservation [1]. This approach tests the fundamental biological knowledge encoded during pretraining, separate from any benefits of transfer learning through fine-tuning [1].

Implementing and evaluating scFMs requires specific computational resources and research reagents. The table below details key components necessary for working with single-cell foundation models.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for scFM Research

| Category | Item | Specification/Description | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | CELLxGENE | >100 million unique standardized cells [8] | Primary data source for pretraining and benchmarking |

| Human Cell Atlas | Multiorgan atlases with broad cell type coverage [9] | Reference data for model evaluation | |

| GEO/SRA Repositories | Thousands of single-cell studies [9] | Supplementary data sources | |

| Benchmark Datasets | Pancreas Dataset | Data from five different sources [1] | Evaluation of batch integration capabilities |

| PBMC 12k Dataset | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells [1] | Immune cell profiling benchmarks | |

| Tabula Sapiens | Multiple tissues from the same donors [1] | Cross-tissue integration evaluation | |

| Norman et al. Perturbation Data | 100 single + 124 double gene perturbations [5] | Perturbation prediction benchmarking | |

| Computational Resources | GPU Memory | 16GB+ recommended for model fine-tuning | Handling large transformer models |

| System RAM | 32GB+ for processing large datasets | Efficient data loading and processing | |

| Storage | TB-scale for pretraining datasets | Storing millions of single-cell profiles |

Critical Analysis & Practical Recommendations

The benchmarking data reveals a nuanced landscape for single-cell foundation models. While scFMs show promise as versatile tools for diverse applications, they currently face significant limitations that researchers must consider when selecting computational approaches.

Context-Dependent Model Performance

A critical finding across multiple studies is that no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks [3]. Performance is highly dependent on the specific application, dataset characteristics, and available computational resources [3]. For example, while scGPT may excel in certain batch integration scenarios, particularly with complex biological batch effects, it may underperform simpler baselines in perturbation prediction [5] [1]. This context-dependence underscores the importance of task-specific model selection rather than seeking a universally superior solution.

When to Choose scFMs vs. Simpler Alternatives

Current evidence suggests that simpler machine learning models often outperform complex foundation models, particularly under resource constraints or for specific tasks like perturbation prediction [3] [5]. The decision to use scFMs should be guided by several factors: dataset size, task complexity, need for biological interpretability, and computational resources [3]. For large, diverse datasets where capturing complex biological relationships is paramount, scFMs may provide benefits. For more focused tasks with limited data, traditional methods may be preferable [3] [1].

Limitations and Future Directions

Significant challenges remain in the development and application of scFMs. The non-sequential nature of omics data continues to present architectural challenges, and current tokenization strategies remain somewhat arbitrary [8]. Data quality inconsistencies across studies and the computational intensity of training and fine-tuning pose practical barriers to widespread adoption [8]. Most importantly, interpreting the biological relevance of latent embeddings and model representations remains nontrivial [8]. Future directions likely include developing more biologically-grounded architectures, incorporating multimodal data, and improving evaluation methodologies to better assess true biological understanding rather than technical benchmarking performance [3] [8].

For researchers navigating this evolving landscape, practical recommendations include: (1) always benchmarking scFMs against simpler baselines for specific tasks of interest, (2) carefully considering whether zero-shot or fine-tuned approaches align with research goals, and (3) utilizing the roughness index (ROGI) as a proxy for model selection in dataset-dependent applications [3]. As the field matures, continued rigorous benchmarking and biological validation will be essential to realizing the potential of foundation models in single-cell genomics.

Masked Language Modeling (MLM) has emerged as a powerful self-supervised learning paradigm for biological sequences, enabling models to learn rich, contextual representations of DNA, RNA, proteins, and single-cell data without extensive labeled datasets. Originally developed for natural language processing, the MLM framework treats biological elements—nucleotides, amino acids, or genes—as tokens in a biological "language." During pre-training, the model learns to predict randomly masked elements based on their context, forcing it to internalize complex structural and functional relationships within biological sequences. This approach has proven particularly valuable in biology, where labeled experimental data is often scarce and expensive to produce, while unlabeled sequence data is abundantly available. The representations learned through MLM create a foundational understanding of biological grammar that can be efficiently adapted to diverse downstream predictive tasks through fine-tuning or zero-shot transfer, establishing MLM as a cornerstone of modern computational biology.

Core Mechanism of Masked Language Modeling

Fundamental Principles and Biological Adaptation

The MLM process operates on a simple but powerful premise: corrupt input sequences by masking random tokens and train the model to reconstruct the original sequence. In biological implementations, this involves several key steps:

Tokenization: Biological sequences are divided into meaningful units—single nucleotides or k-mers for DNA/RNA, amino acids for proteins, or gene identifiers for single-cell data. For example, DNABERT2 uses byte-pair encoding to create optimal vocabulary while Nucleotide Transformer employs non-overlapping k-mers [10].

Masking Strategy: Typically, 15-20% of input tokens are randomly selected for masking. Most are replaced with a special

[MASK]token, some with random tokens, and others left unchanged to encourage robust representation learning [10].Contextual Prediction: The model processes the entire corrupted sequence using transformer architectures, learning to predict original tokens based on bidirectional context rather than just preceding elements [11] [10].

This self-supervised objective forces the model to develop a sophisticated understanding of biological grammar—including structural constraints, evolutionary patterns, and functional motifs—without explicit human labeling. The model essentially learns the "language of life" by filling in biological blanks, developing representations that encode fundamental biological principles through exposure to millions of sequences.

Architectural Implementations Across Biological Domains

While the core MLM principle remains consistent, its architectural implementation varies across biological domains:

RNA Language Models: ERNIE-RNA modifies the standard BERT architecture with base-pairing-informed attention bias, enabling it to capture structural constraints during pre-training without relying on potentially inaccurate predicted structures [11].

Single-Cell Foundation Models: Models like scBERT and scGPT adapt the MLM framework to gene expression data, masking highly-variable genes and predicting their expression levels based on the cellular context [3].

Genomic Language Models: DNABERT2 implements efficient transformer variants with flash attention to handle extremely long genomic sequences, while HyenaDNA uses selective state-space models as an alternative to traditional attention mechanisms [10].

Chemical Language Models: BARTSmiles applies a BART-like denoising approach to SMILES strings, learning rich molecular representations that capture chemical properties and substructure relationships [12].

The following diagram illustrates the core MLM workflow for biological sequences:

Comparative Performance Across Biological Domains

RNA Structure and Function Prediction

MLM-based RNA models demonstrate remarkable capability in capturing structural information directly from sequence data. ERNIE-RNA exemplifies this advancement, having been pre-trained on 20.4 million RNA sequences from RNAcentral and achieving state-of-the-art performance across multiple benchmarks [11].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNA Language Models on Secondary Structure Prediction

| Model | Pre-training Data Size | Architecture | Zero-shot F1-score | Fine-tuned Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERNIE-RNA | 20.4M sequences | Structure-aware BERT | 0.55 (zero-shot) | SOTA across multiple tasks |

| RNA-FM | 23M sequences | Standard Transformer | N/A | Competitive performance |

| UNI-RNA | 1B sequences | Scaled Transformer | N/A | Strong generalist |

| UTR-LM | mRNA UTRs only | Structure-informed BERT | N/A | Specialized for UTRs |

ERNIE-RNA's distinctive innovation lies in its base-pairing-informed attention mechanism, which assigns attention biases according to canonical base-pairing rules (AU=2, CG=3, GU=0.8) [11]. This structural prior enables the model to develop attention maps that directly capture RNA secondary structure through zero-shot prediction, outperforming conventional thermodynamic methods like RNAfold. The model's 12-layer transformer architecture with 12 attention heads and ~86 million parameters effectively captures both local and global RNA features in its attention maps (L×L×156) and token embeddings (12×768×L) [11].

Single-Cell Data Representation

In single-cell transcriptomics, MLM-based foundation models (scFMs) face the unique challenge of representing unordered, high-dimensional gene expression data rather than sequential data. The benchmark evaluation of six prominent scFMs reveals nuanced performance across different task types [3].

Table 2: Single-Cell Foundation Model Performance Across Task Types

| Model | Cell Type Annotation | Batch Integration | Perturbation Response | Clinical Prediction | Biological Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer | Strong | Moderate | Variable | Moderate | High |

| scGPT | Strong | Strong | Strong | Strong | Medium |

| UCE | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| scFoundation | Strong | Strong | Variable | Strong | Medium |

| LangCell | Moderate | Strong | N/A | N/A | High |

| scCello | Variable | Moderate | N/A | N/A | Medium |

Notably, the benchmark introduced novel ontology-informed evaluation metrics including scGraph-OntoRWR (measuring consistency of captured cell type relationships with biological knowledge) and Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (measuring ontological proximity between misclassified cell types) [3]. A key finding was that no single scFM consistently outperformed others across all tasks, emphasizing that model selection must be tailored to specific applications based on dataset size, task complexity, and computational resources [3].

Genomic Sequence Modeling

For genomic DNA sequences, the representational power of MLM-based gLMs shows more mixed results. A comprehensive evaluation of pre-trained gLMs including Nucleotide Transformer, DNABERT2, and HyenaDNA assessed their performance on six regulatory genomics tasks without fine-tuning [10].

Table 3: Genomic Language Model Performance on Regulatory Prediction Tasks

| Model | Architecture | Tokenization | Pre-training Data | Performance vs. One-hot Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Transformer | BERT-style | k-mers | 850 species + human genomes | Comparable or slightly better |

| DNABERT2 | Efficient Transformer | Byte-pair | 850 species | Comparable |

| HyenaDNA | Selective State-Space | Single nucleotide | Human genome | Comparable |

| GPN | Dilated Convolution | Single nucleotide | A. thaliana + related species | Comparable |

Surprisingly, representations from pre-trained gLMs failed to provide substantial advantages over conventional supervised models using one-hot encoded sequences across tasks including predicting cell-type-specific regulatory activity from lentiMPRA data, chromatin profile prediction, and transcription factor binding prediction [10]. This suggests current gLMs may not adequately capture cell-type-specific functional elements during pre-training, highlighting a significant limitation in their application to regulatory genomics.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating MLM Representations

Zero-shot RNA Secondary Structure Prediction

ERNIE-RNA's structural capabilities were evaluated through a rigorous zero-shot prediction protocol [11]:

Attention Map Extraction: Compute attention maps from the first transformer layer (L×L×156 dimensions for sequence length L and 12 layers with 12 attention heads each).

Contact Map Derivation: Process raw attention weights through a ResNet-based post-processing network to convert them into base-pairing probabilities.

Performance Benchmarking: Compare predicted structures against experimentally derived structures using precision, recall, and F1-score metrics.

Comparative Methods: Evaluate against thermodynamic methods (RNAfold, RNAstructure) and other RNA language models without structural priors.

This protocol demonstrated that ERNIE-RNA's attention maps naturally capture RNA architecture without explicit structural supervision during training, achieving an F1-score up to 0.55 in zero-shot prediction [11].

Single-Cell Foundation Model Benchmarking

The evaluation framework for scFMs employed a comprehensive approach to assess biological relevance and practical utility [3]:

Task Selection: Two gene-level and four cell-level tasks including batch integration, cell type annotation, cancer cell identification, and drug sensitivity prediction.

Dataset Curation: Five datasets with diverse biological conditions and seven cancer types with four drugs for clinical relevance assessment.

Evaluation Metrics: Twelve metrics spanning unsupervised, supervised, and novel knowledge-based approaches including scGraph-OntoRWR and LCAD.

Baseline Comparison: Compare against traditional methods including HVG selection, Seurat, Harmony, and scVI.

Zero-shot Protocol: Evaluate pretrained embeddings without fine-tuning to assess inherent biological knowledge.

This multifaceted protocol revealed that while scFMs capture meaningful biological relationships, simpler models sometimes outperform them on specific tasks, particularly under resource constraints [3].

Visualization of MLM Applications in Biology

The application of MLM across biological domains involves specialized architectural adaptations. The following diagram illustrates three major implementations in RNA, single-cell, and genomic modeling:

Emerging Architectures and Future Directions

Beyond Transformer Architectures

While transformer-based architectures currently dominate biological MLM, emerging architectures show significant promise:

xLSTM Variants: The Bio-xLSTM suite adapts the recently proposed xLSTM architecture for biological sequences, offering linear runtime dependency on sequence length compared to transformers' quadratic scaling [13]. This enables handling of longer genomic contexts and more efficient in-context learning for protein and chemical sequences.

State-Space Models: Models like HyenaDNA and Mamba provide alternative sequence modeling approaches with improved computational efficiency for very long sequences [10] [13].

Hybrid Approaches: Architectures combining convolutional networks with recurrent components (CGRN) have demonstrated strong performance in resource-constrained settings, achieving 73.1% F1-score on secondary structure prediction and 84% on intrinsically disordered region prediction with fewer parameters [14].

Specialized Biological Priors

The most successful biological MLM implementations incorporate domain-specific knowledge:

Structural Priors: ERNIE-RNA demonstrates that incorporating base-pairing rules as attention biases significantly enhances structural awareness without compromising generalizability [11].

Evolutionary Context: Models like Nucleotide Transformer pre-trained on multiple species capture evolutionary constraints that improve functional prediction [10].

Multi-scale Modeling: Effective biological MLMs capture both local motifs and global sequence organization, often through hierarchical architectures or multi-head attention mechanisms that specialize in different granularities.

Essential Research Reagents for MLM in Biology

Table 4: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Biological MLM Research

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | RNAcentral, UniProt, NCBI Taxonomy | Pre-training data sources | Public |

| Benchmark Datasets | lentiMPRA, AIDA v2, CellxGene | Evaluation and validation | Public |

| Tokenization Tools | SentencePiece, Byte-pair encoding | Sequence preprocessing | Open source |

| Model Architectures | Transformer variants, xLSTM, SSMs | Model implementation | Open source |

| Evaluation Metrics | scGraph-OntoRWR, LCAD, F1-score | Performance assessment | Custom |

| Visualization Tools | Attention map visualization, UMAP | Interpretation and analysis | Mixed |

Masked Language Modeling has fundamentally transformed computational biology by enabling models to learn rich biological representations from unlabeled sequence data. The core MLM principle remains consistent across domains, but successful implementation requires careful adaptation to biological specifics—structural priors for RNA, expression patterns for single-cell data, and evolutionary context for genomics. Current evidence suggests that MLM-based models excel when they incorporate domain knowledge, as demonstrated by ERNIE-RNA's structural awareness and scFMs' capture of cell type relationships. However, limitations remain, particularly in genomic applications where simple one-hot encoding sometimes competes with sophisticated pre-trained representations. The emerging landscape of biological MLM is increasingly diverse, with transformer architectures being complemented by efficient alternatives like xLSTM and state-space models. Future progress will likely depend on developing better biological priors, more sophisticated evaluation methodologies, and architectures that can scale to handle the full complexity of biological systems while remaining computationally feasible for research laboratories.

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) represent a revolutionary approach in computational biology, designed to learn universal patterns from massive single-cell transcriptomics data. These models, including prominent examples like Geneformer, scGPT, and scFoundation, leverage transformer architectures pretrained on millions of cells with the goal of creating foundational biological knowledge that can be adapted to various downstream tasks [8]. The core premise is that through exposure to vast and diverse datasets, scFMs can learn the fundamental "language" of cells, where individual cells are treated analogously to sentences and genes or genomic features as words or tokens [8]. This approach promises to overcome the challenges of high sparsity, dimensionality, and noise inherent in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data [3].

However, a critical gap has emerged between the intended capabilities of these models during their design and pretraining phase and their actual performance on real-world biological tasks. While scFMs are theorized to excel in zero-shot settings—where pretrained embeddings are used directly without task-specific fine-tuning—rigorous benchmarking has revealed significant limitations in this paradigm [1]. Understanding this gap is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who seek to leverage these powerful tools for biological discovery and clinical applications, particularly in scenarios where labeled data for fine-tuning is unavailable or impractical to obtain.

Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Task Types

Cell-Type Clustering and Annotation

Cell-type identification represents a fundamental application in single-cell analysis where scFMs were expected to demonstrate strong performance. However, comprehensive benchmarking reveals that in zero-shot settings, foundation models frequently underperform simpler established methods. The following table summarizes performance comparisons across multiple datasets, measured by Average BIO (AvgBIO) score, where higher values indicate better performance:

| Model/Dataset | Pancreas | PBMC (12k) | Tabula Sapiens | Immune |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVG | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.67 |

| Harmony | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.64 |

| scVI | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.65 |

| scGPT | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.59 |

| Geneformer | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

Table 1: Cell-type clustering performance (AvgBIO score) across models and datasets. HVG (Highly Variable Genes) and established methods like Harmony and scVI consistently outperform scFMs in zero-shot settings [1].

Notably, the simple approach of selecting highly variable genes (HVG) outperformed both scGPT and Geneformer across all metrics and datasets [1]. While pretraining provides some benefit—with scGPT showing improvement over randomly initialized models—the performance gains are inconsistent and do not reliably surpass simpler alternatives, even when evaluation datasets were included in the pretraining corpus [1].

Batch Integration Performance

Batch integration, which aims to remove technical artifacts while preserving biological signal, is another critical task for single-cell analysis. The performance of scFMs in zero-shot batch integration has been systematically evaluated using metrics that balance batch mixing (iLISI) and biological conservation (cLISI):

| Model | Pancreas (iLISI) | PBMC (cLISI) | Tabula Sapiens (iLISI) | Immune (cLISI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVG | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| Harmony | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.87 |

| scVI | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| scGPT | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.80 |

| Geneformer | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.59 |

Table 2: Batch integration performance across models and datasets. Geneformer consistently underperforms, while scGPT shows variable results depending on dataset characteristics [1].

Qualitative assessment reveals that while Geneformer's embeddings primarily cluster by batch effects rather than cell type, scGPT offers some separation of cell types but still exhibits batch-driven structure in dimensionality reductions [1]. The superior performance of HVG highlights that complex foundation models do not necessarily capture more biologically meaningful representations than carefully selected gene subsets.

Perturbation Effect Prediction

Predicting cellular responses to genetic perturbations represents a particularly challenging task where scFMs were expected to demonstrate emergent capabilities. However, benchmarking studies reveal significant limitations:

| Model | Double Perturbation L2 Distance | Seen Perturbation Performance | Unseen Perturbation Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Baseline | 1.02 | 1.15 | 1.24 |

| No Change Baseline | 1.31 | 1.42 | 1.48 |

| scGPT | 1.85 | 1.91 | 2.02 |

| Geneformer* | 2.12 | 2.24 | 2.31 |

| scFoundation | 1.79 | 1.84 | 1.95 |

| UCE* | 1.96 | 2.08 | 2.17 |

Table 3: Perturbation effect prediction performance (lower L2 values indicate better performance). Models marked with * were repurposed with linear decoders as they weren't specifically designed for this task. Simple baselines outperform foundation models [15].

In predicting genetic interactions, none of the deep learning models outperformed the "no change" baseline, and all models predominantly predicted buffering interactions while rarely correctly identifying synergistic interactions [15]. Furthermore, a linear model using pretrained embeddings from scFoundation and scGPT performed as well or better than the full foundation models with their built-in decoders, suggesting that the learned representations provide limited additional value for this task [15].

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Methodologies

Zero-Shot Evaluation Framework

The critical evaluation of scFMs requires rigorous experimental protocols that assess their performance without fine-tuning, as this most accurately reflects many real-world discovery scenarios. The standard zero-shot evaluation protocol involves:

Embedding Extraction: Precomputed cell embeddings are generated from the frozen pretrained models without any parameter updates or fine-tuning [1]. This assesses the intrinsic quality of representations learned during pretraining.

Task-Specific Evaluation: The embeddings are used directly for downstream tasks including:

- Cell-type clustering: Evaluating separation of known cell types using metrics like Average BIO score and Average Silhouette Width (ASW) [1].

- Batch integration: Assessing removal of technical artifacts while preserving biological variation using metrics like iLISI and cLISI [1].

- Perturbation prediction: Measuring ability to predict transcriptomic changes after genetic perturbations using L2 distance between predicted and observed expression [15].

Baseline Comparison: Performance is compared against established methods including HVG selection, Harmony, and scVI, as well as simple mathematical baselines for perturbation prediction [1] [15].

This evaluation strategy has proven essential for revealing limitations not apparent in fine-tuned scenarios, providing a more realistic assessment of model capabilities for exploratory research where labels are unavailable [1].

Benchmarking Datasets and Quality Control

Robust benchmarking requires diverse, high-quality datasets with validated annotations. Key datasets used in scFM evaluation include:

- Pancreas Dataset: Combines data from five different sources with known batch effects [1].

- Tabula Sapiens: A comprehensive reference atlas with carefully annotated cell types across tissues [1].

- Immune Datasets: Including PBMC (Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell) datasets that capture immune cell diversity [1].

- Perturbation Datasets: CRISPR-based perturbation data from Norman et al. and Replogle et al. for evaluating perturbation prediction [15].

To mitigate the risk of data leakage and ensure fair evaluation, independent unbiased datasets like the Asian Immune Diversity Atlas (AIDA) v2 from CellxGene are increasingly used [3]. Additionally, the Pretraining Data Influence analysis examines performance on datasets that were either included or excluded from model pretraining to assess generalization versus memorization [1].

Diagram 1: ScFM evaluation workflow showing the performance gap between intended and actual use.

Architectural Foundations and Technical Implementation

Model Architectures and Pretraining Strategies

Current scFMs predominantly leverage transformer architectures, but with significant modifications to accommodate the unique characteristics of single-cell data:

| Model | Architecture Type | Pretraining Data Scale | Tokenization Strategy | Positional Encoding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer | Encoder | 30 million cells | Rank-based gene ordering | Yes |

| scGPT | Decoder | 33 million cells | Value binning + HVGs | No |

| UCE | Encoder | 36 million cells | Genomic position ordering | Yes |

| scFoundation | Encoder-Decoder | 50 million cells | Full gene set | No |

Table 4: Architectural variations across prominent single-cell foundation models [3].

Unlike natural language, gene expression data lacks inherent sequential ordering, necessitating specialized tokenization approaches. Common strategies include ranking genes by expression levels within each cell, binning expression values, or using normalized counts directly [8]. These approaches represent fundamental engineering decisions that significantly impact model performance and biological relevance.

Attention Mechanisms and Biological Interpretation

The attention mechanisms in transformer architectures theoretically enable scFMs to learn gene-gene interactions and regulatory relationships. However, interpreting these attention weights as direct biological pathways remains challenging [8]. The discrepancy between theoretical capability and practical interpretability represents a significant hurdle in bridging the intended-actual use gap.

Specialized evaluation metrics like scGraph-OntoRWR have been developed to quantitatively assess whether the relational structure of cell types captured by scFM embeddings aligns with established biological knowledge from cell ontologies [3]. Similarly, the Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD) metric measures the ontological proximity between misclassified cell types, providing a biologically grounded assessment of error severity [3].

Diagram 2: Architectural components and information flow in single-cell foundation models.

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in scFM Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | CELLxGENE, Human Cell Atlas, PanglaoDB, GEO/SRA | Provide standardized, annotated single-cell datasets for model pretraining and evaluation [8] |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | PertEval-scFM, scGraph-OntoRWR, LCAD metrics | Enable standardized evaluation of model performance across diverse biological tasks [3] [16] |

| Baseline Methods | HVG selection, Harmony, scVI, additive perturbation models | Provide critical performance comparisons to assess actual value of complex scFMs [1] [15] |

| Biological Ontologies | Cell Ontology, Gene Ontology, Protein-protein interaction networks | Offer prior biological knowledge for designing biologically meaningful evaluation metrics [3] |

| Computational Infrastructure | GPU clusters (A100), high-performance computing environments | Enable training and evaluation of large-scale models with millions of parameters and training examples [3] |

Table 5: Essential research resources for scFM development and evaluation.

The comprehensive benchmarking of single-cell foundation models reveals a significant gap between their intended capabilities during pretraining and their actual performance on real-world biological tasks. While scFMs represent a theoretically promising approach for learning universal biological representations, their zero-shot performance frequently fails to surpass simpler, established methods across critical tasks including cell-type annotation, batch integration, and perturbation prediction [1] [15].

This performance gap underscores several critical considerations for researchers and drug development professionals:

Task-Specific Model Selection: No single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, emphasizing the need for tailored model selection based on dataset size, task complexity, and available computational resources [3].

Practical Recommendations: For standard analyses like cell-type clustering and batch correction, established methods like Harmony and scVI currently provide more reliable performance. For perturbation prediction, simple linear baselines remain surprisingly competitive [1] [15].

Future Development Directions: Bridging the intention-reality gap will require innovations in pretraining objectives that better align with biological reasoning, improved evaluation metrics that capture biological relevance, and architectural refinements that more effectively model gene regulatory networks [3] [8].

As the field matures, rigorous zero-shot evaluation must become standard practice to accurately assess the true capabilities and limitations of these powerful models. By maintaining a critical perspective and grounding expectations in empirical evidence, the research community can progressively narrow the gap between the intended and actual utility of single-cell foundation models in biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) are large-scale deep learning models, typically based on transformer architectures, pretrained on millions of single-cell transcriptomes to learn the fundamental 'language' of cells [9] [8]. A core promise of these models is their potential for zero-shot learning—the ability to extract biologically meaningful insights from new data using only their pretrained representations, without any task-specific fine-tuning [3]. This capability is crucial for applications where labeled data is scarce, such as in the study of rare cell types or early-stage drug discovery. However, as the field rapidly advances, a critical question remains: do the latent embeddings generated by scFMs in a zero-shot setting truly capture meaningful biology, or are they merely sophisticated technical artifacts? This guide objectively compares the zero-shot performance of leading scFMs against traditional methods and simpler baselines, synthesizing evidence from recent comprehensive benchmarks to address this pivotal question.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Zero-Shot Performance

Independent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the zero-shot embeddings of scFMs across a range of biologically relevant tasks. The table below summarizes the performance of several prominent models against established baseline methods.

Table 1: Performance of scFMs and Baselines on Cell-Level Tasks (Summarized from [3])

| Model / Baseline | Batch Integration | Cell Type Annotation | Cancer Cell Identification | Drug Sensitivity Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | Robust | High Accuracy | Strong | Strong |

| Geneformer | Moderate | Moderate | Variable | Moderate |

| scFoundation | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong (Gene-level) |

| UCE | Variable | Variable | Not Top Performer | Not Top Performer |

| LangCell | Variable | Variable | Not Top Performer | Not Top Performer |

| scCello | Variable | Variable | Not Top Performer | Not Top Performer |

| Seurat (Baseline) | Effective | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Harmony (Baseline) | Effective | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| scVI (Baseline) | Effective | N/A | N/A | N/A |

A key finding across benchmarks is that no single scFM consistently outperforms all others across every task [3]. Model performance is highly dependent on the specific application, dataset size, and biological context. While top-performing scFMs like scGPT demonstrate robust and versatile capabilities, simpler machine learning models can be more efficient and equally effective for specific datasets, particularly under computational constraints [3].

Performance on Gene-Level and Perturbation Tasks

Benchmarks evaluating the prediction of gene-gene relationships and perturbation responses reveal critical limitations of current scFMs.

Table 2: Performance on Gene-Level and In Silico Perturbation Tasks

| Task | Top Performing Models | Key Finding | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double Perturbation Effect Prediction | Simple 'Additive' Baseline (Sum of LFCs) | No deep learning model outperformed the simple additive baseline. | [5] |

| Genetic Interaction Prediction | Simple 'No Change' Baseline | No model improved upon the 'no change' baseline for predicting genetic interactions. | [5] |

| Unseen Single Perturbation Prediction | Linear Model with Pretrained Embeddings | A simple linear model using embeddings from perturbation data outperformed foundation models. | [5] |

| Gene Function & Relationship Analysis | Geneformer, scFoundation | Effective for gene-level tasks, benefiting from pretraining. | [3] [6] |

Notably, a landmark study in Nature Methods concluded that for predicting transcriptome changes after genetic perturbations, "current foundation models did not perform better than deliberately simplistic linear prediction models," despite requiring significantly more computational resources for fine-tuning [5].

Evaluating Biological Relevance: Methodologies and Metrics

To determine if scFMs capture meaningful biology, researchers have moved beyond simple accuracy metrics to develop novel evaluation protocols that directly probe the biological coherence of model embeddings.

Core Experimental Protocols for Zero-Shot Evaluation

The following workflow outlines a standardized protocol for evaluating the biological relevance of zero-shot scFM embeddings, as employed in recent benchmarks [3].

Workflow for Zero-Shot Biological Evaluation

- Feature Extraction: The scFM processes a held-out single-cell dataset to generate latent embeddings for each cell and/or gene without any fine-tuning. The model's internal knowledge is thus probed in a zero-shot manner [3].

- Application to Downstream Tasks: These frozen embeddings are directly used for various cell-level and gene-level tasks, such as:

- Cell Type Annotation: Clustering the embeddings and assessing if known cell types group together.

- Batch Integration: Evaluating how well the embeddings mix cells from different technical batches while preserving biological separation.

- Clinically Relevant Predictions: Testing performance on tasks like cancer cell identification or drug sensitivity prediction [3].

- Quantitative Evaluation with Novel Metrics:

- scGraph-OntoRWR: This metric measures the consistency between the relational structure of cell types captured by the scFM embeddings and the known relationships in established biological ontologies (like the Cell Ontology). A high score indicates the model has learned biologically meaningful relationships between cell types [3].

- Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD): For cell type annotation errors, this metric assesses the severity of the error by measuring the ontological proximity between the misclassified cell type and the correct one. A smaller LCAD indicates a less severe, more biologically plausible error [3].

- Roughness Index (ROGI): This index quantifies the smoothness of the cell-property landscape in the latent space. A smoother landscape (lower roughness) suggests that the embeddings capture continuous biological transitions, making it easier for downstream models to learn and generalize [3].

Key Findings from Biological Evaluation

The application of these sophisticated metrics has yielded critical insights:

- Captured Biological Relationships: Zero-shot scFM embeddings demonstrably capture biologically meaningful insights into the relational structure of genes and cells. The scGraph-OntoRWR metric confirms that the relationships between cell types in the embedding space align with prior biological knowledge [3].

- Smoother Latent Landscapes: The performance improvement of scFMs in downstream tasks is linked to the creation of a smoother latent landscape. The ROGI metric verifies that this reduced complexity makes it less difficult for task-specific models to learn effectively [3].

- Limitations in Complex Prediction: Despite capturing biological relationships, scFMs struggle with the complex, nonlinear task of predicting genetic perturbation effects, often being outperformed by simple additive models of logarithmic fold changes [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key resources and computational tools essential for conducting rigorous evaluations of scFM biological relevance.

Table 3: Essential Resources for scFM Evaluation

| Resource / Reagent | Function in Evaluation | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Annotated Single-Cell Atlases | Provide high-quality, biologically diverse benchmark datasets with ground-truth labels. | CZ CELLxGENE Census [9] [7], Human Cell Atlas [9], Asian Immune Diversity Atlas (AIDA) v2 [3] |

| Perturbation Datasets | Enable benchmarking of in silico perturbation predictions against experimental data. | CRISPRa/i screens (e.g., from Replogle et al.) [5], Perturb-seq data [17] |

| Standardized Benchmarking Frameworks | Offer unified APIs and protocols for fair model comparison, mitigating effects of coding heterogeneity. | BioLLM framework [6] |

| Biological Ontologies | Provide the formal, hierarchical knowledge of gene/cell relationships required for novel metrics. | Cell Ontology, Gene Ontology [3] [5] |

| Visualization & Analysis Suites | Allow researchers to interactively explore embeddings and model predictions. | CELLxGENE Explorer [7], Integrated chat-based tools like CellWhisperer [7] |

The evidence from comprehensive benchmarks indicates that the answer to the critical question is nuanced. Yes, zero-shot scFMs do capture meaningful biology, as evidenced by their ability to encode biologically consistent cell-type relationships and create latent spaces that facilitate various downstream tasks [3]. However, this capability is not universal nor superior in all contexts. Specifically, their performance in predicting genetic perturbation effects is currently lagging and can be matched or exceeded by simpler, non-foundation model approaches [5].

The field is moving toward more biologically grounded evaluation. The introduction of ontology-informed metrics like scGraph-OntoRWR and LCAD represents a significant advance beyond purely technical benchmarks. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting an scFM requires careful consideration of the specific biological question, dataset size, and available resources. Tools like the BioLLM framework and the ROGI index can provide practical guidance for this model selection process [3] [6]. Future progress will likely depend on richer pretraining data that incorporates multimodal information and the development of more sophisticated model architectures designed to better capture causal biological mechanisms.

A Practical Framework for Applying Zero-Shot scFM Embeddings

In single-cell genomics, foundation models (scFMs) are trained on millions of cells to learn universal biological principles, treating individual cells as sentences and genes or genomic features as words or tokens [9] [8]. The latent representations, or embeddings, generated by these models serve as the foundational layer for a wide range of downstream analytical tasks. The evaluation of these zero-shot embeddings—those derived directly from pretrained models without task-specific fine-tuning—is crucial for assessing the intrinsic biological knowledge a model has captured. This guide provides a systematic framework for extracting and benchmarking embeddings from prominent single-cell foundation models, enabling researchers to quantitatively evaluate embedding quality within the broader context of zero-shot scFM research.

The field of single-cell foundation models has seen the rapid development of several architecturally distinct models. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of six prominent scFMs, which represent the current state-of-the-art and are the primary subjects of this embedding extraction guide.

Table 1: Key Single-Cell Foundation Models for Embedding Extraction

| Model Name | Omics Modalities | Model Parameters | Pretraining Dataset Scale | # Input Genes | # Output Dimension | Primary Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer [18] [3] | scRNA-seq | 40 M | 30 M cells | 2048 (ranked) | 256 / 512 | Transformer Encoder |

| scGPT [18] [3] | scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, CITE-seq, Spatial | 50 M | 33 M cells | 1200 HVGs | 512 | Transformer Encoder with attention mask |

| UCE [18] [3] | scRNA-seq | 650 M | 36 M cells | 1024 (sampled & ordered) | 1280 | Transformer Encoder |

| scFoundation [18] [3] | scRNA-seq | 100 M | 50 M cells | ~19,000 | 3072 | Asymmetric Encoder-Decoder |

| LangCell [3] | scRNA-seq | 40 M | 27.5 M scRNA-text pairs | 2048 (ranked) | 256 | Transformer Encoder |

| scCello [18] | scRNA-seq | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Core Architectural and Tokenization Concepts

A fundamental challenge in applying transformer architectures to single-cell data is the non-sequential nature of gene expression data. Unlike words in a sentence, genes in a cell have no inherent ordering [9] [8]. To overcome this, scFMs employ various tokenization strategies that define how a cell's genetic information is converted into a sequence of model inputs:

- Ranking by Expression: A common strategy is to rank genes within each cell by their expression levels and feed the ordered list of top genes as the 'sentence' (e.g., Geneformer, LangCell) [9] [8].

- Value Binning/Projection: Other models, like scGPT, partition gene expression values into bins or use projections to create the input tokens [3].

- Genomic Position: The UCE model uniquely orders sampled genes by their genomic positions [3].

The input layers of these scFMs typically combine gene embeddings (analogous to word embeddings), value embeddings (for expression levels), and sometimes positional embeddings to represent the imposed gene order [18] [3].

Quantitative Benchmarking of Zero-Shot Embedding Performance

A comprehensive benchmark evaluating the zero-shot embedding performance of the six scFMs against established baseline methods provides critical quantitative data for model selection [18] [3]. The evaluation encompassed two gene-level and four cell-level tasks, assessed using 12 metrics.

Performance on Gene-Level and Cell-Level Tasks

Table 2: Benchmarking Results of scFM Zero-Shot Embeddings Across Key Tasks

| Model | Gene Function Prediction (GO Terms) | Tissue Specificity Prediction | Batch Integration (Pre-clinical) | Cell Type Annotation | Cancer Cell Identification | Drug Sensitivity Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer | Moderate | Moderate | Good | Good | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| scGPT | Good | Good | Good | Good | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| UCE | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| scFoundation | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| LangCell | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| scCello | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Traditional Baseline (e.g., scVI, Seurat) | Simpler models can be more efficient and adaptive for specific, resource-constrained tasks. |

Key Benchmarking Findings: The study revealed that no single scFM consistently outperformed all others across every task, emphasizing that model selection must be tailored to the specific application [18] [3]. Pretrained zero-shot scFM embeddings were confirmed to capture meaningful biological insights into the relational structure of genes and cells, which benefits downstream tasks. The performance improvement was linked to a smoother cell-property landscape in the pretrained latent space, which reduces the difficulty of training task-specific models [18] [3].

Novel Biological Evaluation Metrics

To move beyond technical metrics, the benchmark introduced novel cell ontology-informed metrics to provide a biologically grounded perspective on embedding quality [18] [3]:

- scGraph-OntoRWR: Measures the consistency of cell type relationships captured by scFM embeddings with prior biological knowledge encoded in cell ontologies.

- Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD): Assesses the severity of errors in cell type annotation by measuring the ontological proximity between misclassified cell types and their true labels. A smaller LCAD indicates a less severe error (e.g., confusing two types of T cells vs. confusing a T cell with a neuron).

Step-by-Step Embedding Extraction Protocols

This section details the practical methodology for extracting zero-shot cell and gene embeddings from the featured scFMs, following a standardized workflow.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Extracting Embeddings from scFMs

Data Preprocessing and Tokenization

The first step involves preparing your raw single-cell RNA sequencing count matrix for model input. This typically includes normalization and log-transformation to make the data suitable for the model. Following preprocessing, the critical step of tokenization begins, where models differ significantly in their approach [18] [3]:

- For Geneformer/LangCell: For each cell, genes are ranked by their expression value. The top 2048 genes (or another specified number) are selected and input to the model in this rank order. The expression value is often incorporated via an ordering mechanism or a separate value embedding [18] [3] [9].

- For scGPT: The 1200 most highly variable genes (HVGs) across the dataset are selected. The expression values for these genes are then often transformed using a binning strategy before being fed into the model [3].

- For UCE: A unique two-step process is used: 1) 1024 non-unique genes are sampled with probability proportional to their expression, and 2) these genes are then ordered by their genomic positions to create the input sequence [3].

- For scFoundation: The model is designed to accept a comprehensive input of all ~19,000 human protein-encoding genes, using a value projection to handle the expression levels [3].

Model Inference and Embedding Extraction

After tokenization, a zero-shot forward pass is performed through the pretrained model. The extraction point for the embeddings varies by model architecture and intended use:

- Cell Embedding Extraction: Most models produce a dedicated embedding vector for the entire cell. This is often located at a special

[CLS]-type token prepended to the gene sequence, or is derived from the pooled (e.g., mean) output of all gene token embeddings for that cell [18] [9] [8]. - Gene Embedding Extraction: Gene embeddings can typically be extracted from the input embedding layer of the model or from the output of the first transformer layer. These embeddings represent the model's learned representation of individual genes, contextualized by the massive and diverse pretraining data [18].

The Researcher's Toolkit for scFM Embedding Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for scFM Embedding Evaluation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Evaluation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretrained scFM Weights | Software | Provides the core model for generating zero-shot embeddings. | Ensure model compatibility with your organism (e.g., human/mouse) and omics type. |

| CZ CELLxGENE / Cell Atlas [9] [8] | Data Resource | Provides standardized, high-quality datasets for benchmarking and external validation. | Crucial for mitigating data leakage risks and testing generalizability. |

| scGraph-OntoRWR Metric [18] [3] | Evaluation Metric | Quantifies biological consistency of embeddings using cell ontology. | Requires a well-structured reference ontology (e.g., Cell Ontology). |

| Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD) [18] [3] | Evaluation Metric | Measures semantic severity of cell type misannotation errors. | Provides a more biologically meaningful error analysis than simple accuracy. |

| Roughness Index (ROGI) [18] | Evaluation Metric | Acts as a proxy for downstream task performance by measuring landscape smoothness. | Can help with dataset-specific model selection without running full benchmarks. |

The extraction and evaluation of embeddings are fundamental to understanding and leveraging the power of single-cell foundation models. This guide has outlined the methodologies for obtaining these embeddings from key scFMs and has presented a framework for their rigorous, biologically grounded assessment. The benchmark data confirms that while scFMs are robust and versatile tools that capture profound biological insights, the choice of model is context-dependent. Researchers are encouraged to use the provided protocols and metrics—particularly the novel ontology-based measures—to guide their model selection based on specific task requirements, dataset size, and the critical need for biological interpretability. As the field progresses, future developments will likely focus on standardizing these evaluation practices and improving the interpretability of the latent spaces these powerful models create.

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) represent a paradigm shift in the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data. Trained on millions of single-cell transcriptomes, these models promise to learn universal biological principles that can be applied to diverse downstream tasks without task-specific training, an capability known as zero-shot learning [8]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the potential to accurately identify cell types and states in new datasets without manual annotation or fine-tuning could dramatically accelerate discoveries in cellular biology and therapeutic development. This guide provides an objective comparison of current scFMs, focusing specifically on their zero-shot performance for the core tasks of cell type clustering and annotation, synthesizing evidence from recent rigorous benchmarking studies to inform model selection and application.

Performance Comparison of Single-Cell Foundation Models

Recent comprehensive benchmarks reveal a nuanced landscape where no single scFM consistently outperforms all others across every task and dataset. Performance is highly dependent on factors such as dataset size, biological complexity, and the specific evaluation metric employed [3].

Table 1: Zero-Shot Performance Comparison of scFMs and Baselines on Core Tasks