Harnessing Self-Supervised Learning for scRNA-seq Data: From Foundational Models to Clinical Translation

Self-supervised learning (SSL) is revolutionizing the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data by enabling the extraction of meaningful biological representations from vast, unlabeled datasets.

Harnessing Self-Supervised Learning for scRNA-seq Data: From Foundational Models to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Self-supervised learning (SSL) is revolutionizing the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data by enabling the extraction of meaningful biological representations from vast, unlabeled datasets. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring how SSL frameworks like masked autoencoders and contrastive learning overcome key challenges such as data sparsity, batch effects, and limited annotations. We examine the foundational principles of SSL in single-cell genomics, detail cutting-edge methodological approaches and their applications in drug discovery and disease research, address critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world implementation, and present rigorous validation and comparative analyses against traditional methods. The integration of SSL into single-cell analysis pipelines promises to accelerate biomarker discovery, enhance drug response prediction, and advance precision medicine initiatives.

The SSL Revolution in Single-Cell Genomics: Core Concepts and Transformative Potential

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm in machine learning, enabling models to learn meaningful representations from vast, unlabeled datasets. While this approach has revolutionized natural language processing and computer vision, its application to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data is now advancing transcriptomic research. This technical guide explores the core concepts of SSL and its pivotal role in addressing computational challenges in scRNA-seq analysis, including data sparsity, batch effects, and the high cost of manual cell annotation. We provide a comprehensive overview of SSL frameworks adapted to biological data, benchmark performance across key downstream tasks, and detail experimental protocols for implementation. By integrating quantitative comparisons and visual workflows, this review serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals leveraging SSL for cellular transcriptomics.

Self-supervised learning is a machine learning technique that solves a fundamental challenge: how to learn effective data representations without relying on manually annotated labels. In SSL, the supervisory signal is generated directly from the structure and relationships within the input data itself, rather than from external annotations. This approach transforms unsupervised problems into supervised ones by creating pretext tasks where the model learns to predict hidden or transformed parts of the input from visible portions [1].

The fundamental SSL process involves two primary stages. In the pretext task phase (pre-training), the model learns intermediate data representations by solving an auxiliary task designed to capture underlying structural patterns. This is followed by the downstream task phase (fine-tuning), where the pre-trained model is adapted to specific practical applications, often with limited labeled data [1]. This paradigm has proven particularly powerful in data-rich domains where manual labeling is expensive or impractical.

In natural language processing, SSL has achieved remarkable success through models like BERT, which uses pretext tasks such as masked language modeling—predicting missing words in a sentence based on surrounding context [1]. Similarly, in computer vision, SSL methods employ pretext tasks including patch localization (predicting the relative position of image patches) and context-aware pixel prediction (reconstructing masked image regions) [1]. These approaches enable models to learn rich, generalized representations that transfer effectively to various downstream applications.

The transition of SSL from NLP and computer vision to cellular transcriptomics represents a natural evolution, as scRNA-seq data presents similar challenges of high dimensionality, technical noise, and limited annotations. By adapting SSL frameworks to biological data, researchers can leverage the vast quantities of unlabeled scRNA-seq data to learn fundamental representations of cellular states and functions, ultimately accelerating discoveries in basic biology and therapeutic development.

SSL Frameworks for scRNA-seq Data

The adaptation of self-supervised learning to single-cell genomics requires specialized frameworks that address the unique characteristics of transcriptomic data, including high dimensionality, significant sparsity, and complex biological noise patterns. Several SSL architectures have been developed specifically for scRNA-seq analysis, falling primarily into two categories: contrastive learning methods and masked autoencoders.

Contrastive Learning Methods

Contrastive learning frameworks operate by bringing representations of similar data points (positive pairs) closer together in the embedding space while pushing apart representations of dissimilar points (negative pairs). In scRNA-seq applications, positive pairs are typically created through data augmentation techniques that generate multiple views of the same cell while preserving its biological identity.

The CLEAR (Contrastive LEArning framework) methodology exemplifies this approach. CLEAR creates augmented cell profiles by applying various noise simulations, including Gaussian noise and simulated dropout events, to the original gene expression data. The framework then employs a contrastive loss function that forces the model to produce similar representations for the original and corresponding augmented profile (positive pairs), while producing distant representations for cells of different types (negative pairs) [2]. This approach enables the model to learn representations robust to technical noise while preserving biological signals.

Another contrastive approach, contrastive-sc, adapts self-supervised contrastive learning from computer vision to scRNA-seq data. This method creates two distinct augmented views of each cell by masking an arbitrary random set of genes in each view. The encoder model is trained to minimize the distance between these augmented copies in the representation space, learning to produce similar embeddings despite the masked genes [3]. This architecture has demonstrated strong performance in clustering analyses and maintains computational efficiency.

Masked Autoencoders

Masked autoencoders represent another prominent SSL approach adapted for single-cell data. These models learn to reconstruct randomly masked portions of the input data, forcing the encoder to develop meaningful representations that capture essential patterns and relationships in the data.

In SCG applications, researchers have developed multiple masking strategies with varying degrees of biological insight integration. Random masking applies minimal inductive bias by randomly selecting genes for reconstruction. More sophisticated gene program masking strategies leverage known biological relationships by masking functionally related gene sets. The most specialized approach, isolated masking, intensively utilizes known gene functions by masking isolated sets of genes with specific biological roles, such as transcription factors or pathway components [4].

The scRobust framework combines both contrastive learning and masked autoencoding in a unified Transformer-based architecture. For contrastive learning, scRobust employs a novel cell augmentation technique that generates diverse cell embeddings from random gene sets without dropout. Simultaneously, the model performs gene expression prediction, where the encoder predicts the expression of certain genes through the dot product between a local cell embedding and target gene embeddings [5]. This dual approach enables the model to effectively address scRNA-seq data sparsity while learning biologically meaningful representations.

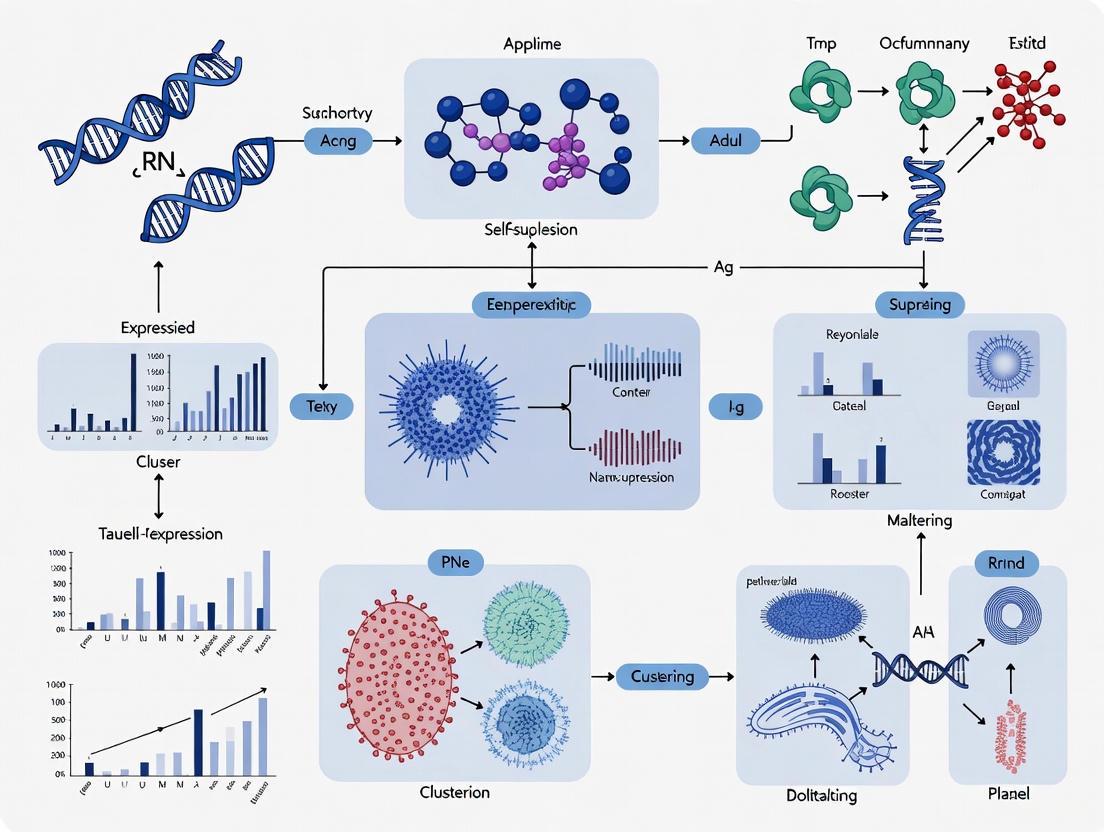

Figure 1: scRobust Framework combining contrastive learning and gene prediction. The model uses cell augmentation to generate multiple views, then learns embeddings through dual pretext tasks.

Benchmarking SSL Performance in scRNA-seq Analysis

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have quantified the performance benefits of SSL across various scRNA-seq analysis tasks. The results demonstrate that SSL approaches consistently outperform traditional supervised methods, particularly in transfer learning scenarios and when dealing with class imbalance.

Cell Type Annotation Performance

Cell type annotation represents a fundamental downstream task where SSL has demonstrated significant improvements. Studies evaluating SSL frameworks on multiple benchmark datasets with varying technologies and cell type complexities have revealed consistent performance gains.

As shown in Table 1, SSL methods achieve superior performance compared to traditional supervised approaches, with particularly notable improvements in identifying rare cell types. For instance, scRobust achieved the highest F1 scores in eight of nine benchmark datasets, demonstrating remarkable capability in classifying challenging cell populations such as CD4+ T Helper 2 cells and epsilon cells, where other methods performed poorly [5]. This enhanced performance with rare cell types highlights SSL's robustness to class imbalance, a common challenge in scRNA-seq analysis.

Table 1: Cell Type Annotation Performance of SSL Methods Across Benchmark Datasets

| Method | Architecture | Average Macro F1 | Performance with 30% Additional Dropout | Rare Cell Type Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scRobust | Transformer + Contrastive Learning | 0.892 | 0.865 | Superior (28% accuracy for CD4+ Th2 vs. <10% for others) |

| CLEAR | Contrastive Autoencoder | 0.847 | 0.801 | Moderate |

| contrastive-sc | Contrastive MLP | 0.832 | 0.785 | Moderate |

| Supervised Baseline | Fully Connected Network | 0.701 | 0.612 | Poor |

| Seurat (Traditional) | Graph-based Clustering | 0.815 | 0.723 | Limited |

The performance advantages of SSL become even more pronounced in challenging conditions with additional artificial dropout. scRobust maintained high performance even with 50% additional dropout, outperforming benchmark methods without additional dropout in several datasets including TM, Zheng sorted, Segerstolpe, and Baron Mouse [5]. This robustness to data sparsity is particularly valuable for analyzing scRNA-seq data from platforms with high dropout rates, such as 10X Genomics Chromium.

Transfer Learning Capabilities

SSL demonstrates particular strength in transfer learning settings, where models pre-trained on large-scale datasets are adapted to smaller, target datasets. Empirical analyses reveal that self-supervised pre-training on auxiliary data significantly boosts performance in both cell-type prediction and gene-expression reconstruction tasks.

For the Tabula Sapiens Atlas, self-supervised pre-training on additional scTab data improved macro F1 scores from 0.272 to 0.308, driven by enhanced classification of specific cell types—correctly classifying 6,881 of 7,717 type II pneumocytes instead of 2,441 [4]. Similarly, for PBMC datasets, SSL improved macro F1 from 0.701 to 0.747, with particularly pronounced benefits for underrepresented cell types [4].

The transfer learning performance gains are highly dependent on the richness of the pre-training dataset. SSL consistently outperforms supervised learning when pre-trained on data from a large number of donors, highlighting the importance of diverse pre-training data for capturing biological variability [4]. This capability enables effective knowledge transfer from large-scale reference atlases to smaller, targeted studies.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing SSL for scRNA-seq analysis requires careful attention to experimental design, data preprocessing, and model training protocols. This section details standardized methodologies for key SSL applications in transcriptomics.

Contrastive Learning Implementation

The contrastive-sc protocol provides a representative framework for implementing contrastive SSL with scRNA-seq data:

Data Preprocessing:

- Quality Filtering: Remove genes expressed in only one cell or less

- Normalization: Normalize expression counts by library size using the scanpy pipeline, dividing each cell by the sum of its counts then multiplying by the median of all cells' total expression values

- Transformation: Apply natural logarithm to normalized data

- Feature Selection: Select top 500 highly variable genes according to dispersion ranking

- Scaling: Scale data to zero mean and unit variance for each gene [3]

Representation Training:

- Data Augmentation: For each input cell, create two augmented views by applying neural network dropout to randomly mask different sets of genes in each view

- Encoder Architecture: Implement a 3-layer fully connected neural network with ReLU activations and batch normalization between layers

- Contrastive Loss: Use the normalized temperature-scaled cross entropy (NT-Xent) loss to minimize distance between augmented versions of the same cell while maximizing distance from other cells

- Training Parameters: Train with Adam optimizer, learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 128, for 500 epochs [3]

Clustering Phase:

- Embedding Extraction: Generate cell embeddings from the trained encoder's representation layer

- Cluster Algorithm: Apply K-means clustering when the number of expected clusters is known, or Leiden community detection otherwise

- Validation: Evaluate clustering quality using adjusted Rand index (ARI) and normalized mutual information (NMI) metrics against expert annotations

Federated SSL for Multi-Institutional Data

The FedSC framework enables collaborative model training across multiple institutions while preserving data privacy—a critical consideration for clinical data:

Federated Learning Setup:

- Local Training: Each participating institution trains a local SSL model on its private scRNA-seq data

- Model Aggregation: A central server periodically aggregates model parameters from local models using federated averaging

- Privacy Preservation: Raw data remains at local institutions; only model parameters are shared [6]

Benchmark Configuration:

- Datasets: Utilize PBMC and mouse bladder cell datasets under both IID (independently and identically distributed) and non-IID data partitions

- Evaluation: Assess clustering performance using ARI, NMI, and silhouette scores under both data distributions

- Comparative Analysis: Compare against centralized training and local-only training baselines [6]

This federated approach enables leveraging decentralized unlabeled scRNA-seq data from multiple sequencing platforms while maintaining data privacy, addressing both technical and ethical challenges in biomedical research.

Figure 2: Standard SSL workflow for scRNA-seq analysis. The approach involves self-supervised pre-training followed by task-specific fine-tuning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing SSL for scRNA-seq research requires both computational tools and biological resources. Table 2 summarizes essential components of the experimental pipeline and their functions in SSL-based transcriptomic analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for SSL in scRNA-seq

| Category | Item | Function in SSL Workflow | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | scTab Dataset | Large-scale pre-training data with ~20M cells across tissues | HLCA, Tabula Sapiens |

| Cell Line Databases | Bulk RNA-seq data for transfer learning | GDSC, CCLE | |

| Benchmark Datasets | Evaluation datasets with ground truth labels | Baron Human, Muraro, PBMC | |

| Computational Tools | scanpy | Standard scRNA-seq preprocessing and analysis | Seurat (R alternative) |

| CLEAR | Contrastive learning framework for clustering | contrastive-sc, scRobust | |

| scGPT | Foundation model for multiple downstream tasks | Geneformer, scBERT | |

| FedSC | Federated learning implementation for privacy | Custom implementations | |

| Biological Assays | 10X Genomics | High-throughput scRNA-seq platform | Smart-seq2 for deeper coverage |

| Cytometry by Time-of-Flight (CyTOF) | Protein expression validation | Imaging mass cytometry | |

| Drug Sensitivity Assays | Ground truth for response prediction | CellTiter-Glo, IncuCyte |

The integration of self-supervised learning with single-cell transcriptomics represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, enabling researchers to extract deeper biological insights from rapidly expanding scRNA-seq datasets. SSL methods have demonstrated superior performance across fundamental analysis tasks including cell type annotation, data integration, and drug response prediction while addressing critical challenges like data sparsity and batch effects.

Looking forward, several emerging trends will likely shape the next generation of SSL applications in transcriptomics. Foundation models pre-trained on massive, diverse cell atlases will enable zero-shot transfer to new biological contexts and species. Multimodal SSL approaches that jointly model transcriptomic, epigenetic, and proteomic data will provide more comprehensive views of cellular states. Federated learning frameworks will facilitate collaborative model development while addressing privacy concerns associated with clinical data [6]. Additionally, interpretable SSL methods like scKAN, which uses Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks to provide transparent gene-cell relationship modeling, will enhance the biological insights derived from these models [7].

As SSL continues to evolve, its impact will extend beyond basic research to therapeutic development. SSL-based drug response prediction models like scDEAL already demonstrate how transfer learning from bulk to single-cell data can identify heterogeneous treatment effects across cell subpopulations [8]. Similarly, SSL-powered target discovery frameworks are enabling repurposing of existing therapeutics for new indications based on cell-type-specific gene signatures [7].

In conclusion, self-supervised learning has fundamentally transformed the analysis of cellular transcriptomics, providing powerful frameworks to leverage the vast quantities of unlabeled scRNA-seq data being generated worldwide. By adapting and extending SSL principles from NLP and computer vision, researchers have developed specialized approaches that address the unique challenges of biological data. As these methods continue to mature and integrate with emerging experimental technologies, they will play an increasingly central role in unraveling cellular complexity and advancing precision medicine.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the measurement of gene expression at the resolution of individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity, identifying novel cell types, and illuminating developmental trajectories that are inaccessible to bulk sequencing approaches [9] [10]. However, the unique data characteristics of scRNA-seq—including high sparsity, significant technical noise, and inherent cellular heterogeneity—present substantial computational challenges for analysis. Simultaneously, self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a powerful machine learning paradigm that learns meaningful representations from unlabeled data by constructing pretext tasks that leverage the inherent structure of the data itself [4] [11]. This technical whitepaper demonstrates how the very characteristics that make scRNA-seq data challenging also make it exceptionally well-suited for SSL approaches.

SSL methods extract information directly from the structure of unlabeled data through pre-training, generating qualitative representations that can be fine-tuned for specific downstream predictive tasks [11]. This approach is particularly valuable in domains where labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain. In single-cell genomics, SSL has shown remarkable potential in addressing key challenges such as technical batch effects, data sparsity, and the integration of diverse datasets [4]. The convergence of scRNA-seq and SSL creates a powerful framework for uncovering biological insights from complex cellular data without relying exclusively on supervised approaches requiring extensive manual labeling.

Fundamental Characteristics of scRNA-seq Data

Data Sparsity and Zero-Inflation

A prominent feature of scRNA-seq data is its sparsity, characterized by a high proportion of zero read counts. This "zero inflation" arises from both biological and technical sources [9]. Biologically, genuine transient states or subpopulations where a gene is not expressed contribute to true zeros. Technically, "dropout" events occur when a transcript is expressed but not detected during sequencing due to limitations in capture efficiency or amplification [9] [12]. The minute amount of mRNA in a single cell must undergo reverse transcription and amplification before sequencing, making the process vulnerable to substantial stochastic molecular losses [12]. This sparsity fundamentally differentiates scRNA-seq from bulk RNA-seq and necessitates specialized computational approaches.

Cellular Heterogeneity

ScRNA-seq captures the natural diversity of cell states and types within seemingly homogeneous populations. While bulk RNA sequencing measures average gene expression across thousands of cells, masking cell-to-cell variation, scRNA-seq reveals this heterogeneity, enabling the identification of rare cell types and continuous transitional states [10]. This heterogeneity is biologically meaningful but presents analytical challenges for traditional methods that assume population homogeneity. Cellular heterogeneity manifests as multimodal distributions in gene expression that reflect distinct cellular identities and functions within tissues, tumors, and developmental systems.

Technical Noise and Batch Effects

Technical noise in scRNA-seq far exceeds that of bulk experiments due to the low starting material and complex workflow. Major sources include:

- Stochastic sampling during library preparation and sequencing

- Variable capture efficiency during reverse transcription

- Amplification biases from PCR or in vitro transcription

- Batch effects introduced by processing conditions across experiments [9] [13] [12]

These technical artifacts manifest as non-biological variability that can obscure genuine biological signals. External RNA spike-ins can help model this technical noise, but challenges remain in distinguishing biological from technical variability, especially for lowly expressed genes [12]. The high dimensionality of scRNA-seq data further exacerbates these issues through the "curse of dimensionality," where noise accumulates across features [13].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of scRNA-seq Data and Their Implications for SSL

| Data Characteristic | Description | Challenge for Analysis | Opportunity for SSL |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Sparsity | 50-90% zero values from biological and technical sources | Reduced statistical power, impedes correlation analysis | SSL pretext tasks can learn to impute missing values and denoise data |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Multimodal expression distributions from diverse cell states | Clustering instability, trajectory inference uncertainties | Rich, natural variation provides diverse self-supervision signals |

| Technical Noise | High variability from molecular sampling and amplification | Obscures biological signals, complicates differential expression | SSL can separate technical artifacts from biological signals in latent space |

| High Dimensionality | 20,000+ genes measured per cell, but correlated structures | Curse of dimensionality, computational burden | Dimensionality reduction via SSL preserves biological meaningful information |

| Batch Effects | Systematic technical differences between experiments | Limits dataset integration and reproducibility | SSL transfer learning enables cross-dataset generalization |

Self-Supervised Learning Approaches for scRNA-seq

Masked Autoencoders for Gene Expression Modeling

Masked autoencoders have emerged as particularly effective SSL approaches for scRNA-seq data, outperforming contrastive methods in many applications [4]. These models randomly mask a portion of the input gene expression features and train a neural network to reconstruct the missing values based on the observed context. This pretext task forces the model to learn the underlying gene-gene relationships and expression patterns that characterize cell states. Different masking strategies can be employed:

- Random masking: Selects genes randomly for masking, introducing minimal inductive bias

- Gene program masking: Masks biologically coherent gene sets (e.g., pathways, co-regulated modules)

- Targeted masking: Focuses on specific gene categories like transcription factors [4]

The model learns a rich representation space that captures essential biological relationships while being robust to the sparse nature of the data. After pre-training on large-scale unlabeled datasets, the encoder can be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks with limited labeled data, demonstrating exceptional transfer learning capabilities [4].

Contrastive Learning Methods

Contrastive SSL methods learn representations by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same cell while distinguishing them from other cells. Techniques like Bootstrap Your Own Latent (BYOL) and Barlow Twins, adapted from computer vision, have shown promise in scRNA-seq applications [4]. These approaches can incorporate domain-specific augmentations such as negative binomial noise and random masking to create meaningful positive pairs for comparison. By learning to identify which augmented views originate from the same cell, the model becomes invariant to technical noise while preserving biologically relevant variation.

Self-Supervised Pre-training for Transfer Learning

A powerful application of SSL in scRNA-seq involves pre-training on large-scale collections like the CELLxGENE census (containing over 20 million cells) followed by fine-tuning on smaller target datasets [4]. This approach leverages the diversity of cell types and experimental conditions in aggregate datasets to build a foundational understanding of gene expression patterns that transfers effectively to new contexts. Empirical analyses demonstrate that models pre-trained with SSL on auxiliary data significantly improve performance on cell-type prediction tasks in target datasets, with macro F1 scores increasing from 0.7013 to 0.7466 in PBMC data and from 0.2722 to 0.3085 in the Tabula Sapiens atlas [4]. This transfer learning capability is particularly valuable for rare cell type identification and in scenarios with limited labeled examples.

Experimental Evidence and Performance Benchmarks

SSL Performance on Cell Type Annotation

Comprehensive benchmarking across multiple datasets and technologies has quantified the benefits of SSL for cell type annotation. Studies evaluating over 1,600 active learning models across six datasets and three technologies demonstrate that SSL approaches significantly outperform random selection, particularly in the presence of cell type imbalance and variable similarity [14]. When combined with strategic cell selection methods, SSL improves annotation accuracy while reducing the manual labeling burden. The incorporation of prior knowledge about cell type markers further enhances these benefits, creating a powerful semi-supervised framework for cellular annotation.

Table 2: Performance of SSL Methods on scRNA-seq Downstream Tasks

| SSL Method | Pretext Task | Downstream Task | Performance Gain | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masked Autoencoder | Random gene masking | Cell-type prediction | +4.5-6.3% macro F1 [4] | Excellent transfer learning capabilities |

| Contrastive Learning (BYOL) | Augmentation invariance | Data integration | Improved batch mixing scores [4] | Robustness to technical variations |

| Self-training with Pseudo-labels | Iterative self-labeling | Rare cell identification | Enhanced recall of rare types [14] | Effective with class imbalance |

| Transfer Learning with SSL | Pre-training on auxiliary data | Cross-dataset annotation | +10-15% on challenging types [4] | Leverages large-scale atlases |

Technical Noise Reduction and Data Imputation

SSL methods have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in distinguishing biological signals from technical artifacts. RECODE, a high-dimensional statistics-based tool for technical noise reduction, leverages principles aligned with SSL to simultaneously address technical noise and batch effects while preserving full-dimensional data [13]. By modeling technical noise as a general probability distribution and applying eigenvalue modification theory rooted in high-dimensional statistics, RECODE effectively mitigates dropout events and sparsity. The upgraded iRECODE platform extends this approach to simultaneously reduce both technical and batch noise, improving relative error metrics by over 20% compared to raw data and by 10% compared to traditional denoising approaches [13].

Cross-Modality Prediction and Data Integration

SSL enables effective integration of scRNA-seq data across platforms, species, and experimental conditions. Methods based on masked autoencoders demonstrate strong zero-shot capabilities, where models pre-trained on large-scale datasets can be directly applied to new datasets without fine-tuning, achieving competitive performance on cell-type annotation [4]. This capability is particularly valuable for emerging datasets where comprehensive labeling is unavailable. Furthermore, SSL facilitates cross-modality prediction, enabling the translation of gene expression patterns across sequencing technologies or even to spatially-resolved transcriptomic data.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Masked Autoencoder Implementation for scRNA-seq

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize raw UMI counts using standard scRNA-seq pipelines (e.g., SCTransform), selecting highly variable genes for analysis while preserving the full gene set for specialized applications.

- Masking Strategy: Implement random masking of 15-30% of input genes following a Bernoulli distribution. For biologically-informed masking, identify gene programs using NMF or pathway databases.

- Architecture: Employ a fully connected encoder-decoder architecture with bottleneck dimensions between 64-512, depending on dataset complexity.

- Training: Optimize reconstruction loss using mean squared error or negative binomial loss for count-based data. Use Adam optimizer with learning rate warmup and decay.

- Fine-tuning: Transfer pre-trained encoder to downstream tasks by replacing decoder with task-specific heads, using reduced learning rates for the encoder weights.

Key Considerations:

- Maintain separate train/validation splits to monitor for overfitting

- Implement early stopping based on validation reconstruction loss

- For large-scale pre-training, leverage multiple GPU training with data parallelism

- Consider gradient checkpointing for memory-intensive full-gene-set models [4]

Contrastive Learning Protocol

Methodology:

- Augmentation Strategy: Generate positive pairs through random masking (10-20% of genes) and negative binomial noise injection.

- Architecture: Implement siamese network architecture with shared weight encoders and projectors mapping to normalized embedding space.

- Loss Function: Apply InfoNCE loss or BYOL's similarity-based loss without negative pairs.

- Training: Use symmetric loss calculation and momentum encoder updates for stability.

- Evaluation: Assess representation quality through linear probing and k-NN classification on held-out datasets. [4] [11]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SSL in scRNA-seq

| Tool/Category | Representative Examples | Function | Applicable SSL Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Preprocessing | SCTransform, Scanpy, Seurat | Normalization, QC, feature selection | Prepares data for SSL pretext tasks |

| Batch Correction | Harmony, MNN, Scanorama | Technical effect removal | Often integrated within SSL pipelines like iRECODE [13] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX | Model implementation | Flexible SSL implementation |

| SSL Libraries | SCARF, VIME, BYOL adaptations | Pre-trained models and methods | Transfer learning to new datasets [11] |

| Large-scale Atlas Resources | CELLxGENE, Tabula Sapiens, HCA | Pre-training data sources | Foundation model development [4] |

| Visualization Tools | UMAP, t-SNE, SCIM | Representation quality assessment | Evaluation of SSL latent spaces |

The unique characteristics of scRNA-seq data—including sparsity, heterogeneity, and technical noise—present challenges that align remarkably well with the strengths of self-supervised learning approaches. SSL methods effectively leverage the natural variation in scRNA-seq data to learn meaningful representations that capture biological signals while remaining robust to technical artifacts. Through techniques like masked autoencoding and contrastive learning, SSL enables accurate cell type annotation, effective data integration, and improved identification of rare cell populations. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve and dataset sizes grow exponentially, SSL provides a scalable framework for extracting biological insights while reducing dependence on costly manual labeling. The convergence of scRNA-seq and SSL represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, enabling more powerful, accurate, and generalizable analysis of cellular heterogeneity and function.

Diagrams

Diagram 1: SSL-scRNA-seq Synergy

Diagram 2: Masked Autoencoder Workflow

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative methodology in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis, enabling researchers to extract meaningful biological insights from vast, unlabeled genomic datasets. SSL methods learn effective data representations by formulating pretext tasks that do not require manual annotations, making them particularly valuable in single-cell genomics where labeled data is often scarce and expensive to obtain. Among the various SSL techniques, two dominant paradigms have risen to prominence: masked autoencoders and contrastive learning. These approaches differ fundamentally in their learning objectives and architectural implementations, yet both aim to overcome pervasive challenges in scRNA-seq data, including high dimensionality, significant sparsity due to dropout events, and technical artifacts such as batch effects. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of these core SSL paradigms, examining their theoretical foundations, methodological adaptations for single-cell data, and performance characteristics across key bioinformatics tasks.

Core Paradigms: Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Masked Autoencoders in Single-Cell Genomics

Masked autoencoders (MAE) belong to the category of generative self-supervised learning methods. Their fundamental principle involves corrupting input data by masking portions of it and training a model to reconstruct the original information from the corrupted version. In the context of scRNA-seq data, this approach has been specifically adapted to handle gene expression profiles.

The core architecture consists of an encoder that processes the non-masked portions of the input and a decoder that reconstructs the complete output. For single-cell data, the masking operation typically involves randomly setting a subset of gene expression values to zero, challenging the model to predict the original expressions based on contextual patterns and gene-gene correlations. This process forces the model to learn meaningful biological relationships within the data rather than merely memorizing patterns.

Several specialized implementations of masked autoencoders have been developed for single-cell genomics:

scMAE: Specifically designed for scRNA-seq clustering, scMAE introduces a masking predictor that captures relationships among genes by predicting whether gene expression values have been masked. The model learns robust cell representations by reconstructing original data from perturbed gene expressions, effectively capturing latent structures and dependencies [15].

Gene Programme Masking: An advanced masking strategy that goes beyond random masking by utilizing known biological relationships. This approach masks groups of functionally related genes (gene programmes) or specifically targets transcription factors, thereby incorporating biological inductive biases into the learning process [4].

The reconstruction objective in masked autoencoders is typically implemented using mean squared error or negative binomial loss functions, which are well-suited for modeling gene expression distributions. Through this process, the model learns a rich, contextualized representation of each cell's transcriptional state that captures complex gene-gene interactions.

Contrastive Learning in Single-Cell Genomics

Contrastive learning operates on a fundamentally different principle from masked autoencoders, falling under the category of discriminative self-supervised learning. Rather than reconstructing inputs, contrastive methods learn representations by comparing and contrasting data points. The core idea is to train models to recognize similarities and differences between samples, effectively mapping similar cells closer together in the embedding space while pushing dissimilar cells farther apart.

The contrastive learning framework relies on several key components:

Data Augmentation: Creating different "views" of the same cell through transformations that preserve biological identity while introducing variations. Common augmentations in scRNA-seq include random masking, Gaussian noise addition, and gene swapping between cells.

Positive and Negative Pairs: Defining which samples should be considered similar (positive pairs) and which should be considered different (negative pairs). Positive pairs are typically different augmented views of the same cell, while negative pairs are representations of different cells.

Contrastive Loss Function: Optimizing the embedding space using objectives like InfoNCE or NT-Xent that simultaneously attract positive pairs and repel negative pairs in the representation space.

Notable contrastive learning implementations for single-cell data include:

CLEAR: A comprehensive framework that employs various augmentation strategies including Gaussian noise, random masking, and a genetic algorithm-inspired crossover operation where "child" cells are created by recombining genes from two "parent" cells. CLEAR demonstrates strong performance across multiple downstream tasks including clustering, visualization, and batch effect correction [2].

scCM: A momentum contrastive learning method specifically designed for integrating large-scale central nervous system scRNA-seq data. scCM brings functionally related cells close together while pushing apart dissimilar cells by comparing gene expression variations, effectively revealing heterogeneous relationships within CNS cell types and subtypes [16].

contrastive-sc: An adaptation of self-supervised contrastive learning framework initially developed for computer vision. This method creates augmented cell views primarily by masking random sets of genes and employs a contrastive loss to minimize distance between augmented versions of the same cell while maximizing distance from other cells [3].

Comparative Analysis: Performance Across Downstream Tasks

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of SSL paradigms across key scRNA-seq tasks

| Task | Metric | Masked Autoencoder | Contrastive Learning | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-type Annotation | Macro F1 Score | 0.7466 (PBMC), 0.3085 (Tabula Sapiens) [4] | Top F1 scores in 8/9 datasets (scRobust) [5] | MAE excels in transfer learning; Contrastive better for rare cell types |

| Data Integration | Batch Correction | Moderate performance | Superior (scCM achieves best Acc, ARI, VMS) [16] | Contrastive learning more effective for multi-dataset integration |

| Clustering | ARI, NMI | Superior performance (scMAE) [15] | Substantially better than most methods (CLEAR) [2] | Both paradigms outperform traditional methods |

| Robustness to Sparsity | Performance with 50% added dropout | -- | Maintains high performance (scRobust) [5] | Contrastive learning shows exceptional noise robustness |

| Cross-modality Prediction | Weighted Explained Variance | Strong performance [4] | Varies by method | MAE shows particular promise for this emerging task |

Task-Specific Performance and Applications

Cell-type annotation represents one of the most fundamental applications in scRNA-seq analysis. Empirical evidence demonstrates that both SSL paradigms significantly improve annotation accuracy compared to supervised baselines, particularly in transfer learning scenarios where models pre-trained on large-scale datasets are fine-tuned on smaller target datasets. Masked autoencoders show remarkable improvements when leveraging auxiliary data, boosting macro F1 scores from 0.7013 to 0.7466 in PBMC datasets and from 0.2722 to 0.3085 in Tabula Sapiens datasets [4]. Contrastive methods like scRobust demonstrate exceptional capability in identifying rare cell types, achieving accuracy scores of 0.28 for CD4+ T Helper 2 cells where other methods scored below 0.10 [5].

For data integration and batch correction, contrastive learning approaches generally outperform masked autoencoders. The scCM method achieves top performance across multiple metrics (Accuracy, ARI, VMS) when integrating complex central nervous system datasets spanning multiple species and disease conditions [16]. This advantage stems from contrastive learning's inherent ability to explicitly model similarities and differences across datasets, effectively separating biological signals from technical variations.

In clustering applications, both paradigms show substantial improvements over traditional methods. scMAE, a masked autoencoder approach, demonstrates superior performance on 15 real scRNA-seq datasets across various clustering evaluation metrics [15]. Similarly, CLEAR, a contrastive method, achieves substantially better Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) scores than most comparison methods across 10 published datasets [2].

When considering robustness to data sparsity, contrastive learning methods exhibit exceptional capability to maintain performance under extreme dropout conditions. scRobust maintains high classification accuracy even with 50% additional artificially introduced dropout events, outperforming other methods that trained on much less sparse data [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementation Frameworks

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational resources for SSL in scRNA-seq

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Platform | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation Models | scGPT, scFoundation, TOSICA | Large-scale pre-training on million-cell datasets |

| Specialized Frameworks | scVI, CLEAR, scRobust, scMAE | Task-specific implementations of SSL paradigms |

| Data Sources | CELLxGENE Census, scTab, Human Cell Atlas | Large-scale reference datasets for pre-training |

| Evaluation Metrics | Macro F1, ARI, NMI, kBET | Standardized performance assessment |

| Augmentation Techniques | Random Masking, Gaussian Noise, Gene Swapping | Creating positive pairs for contrastive learning |

Detailed Methodological Workflows

Masked Autoencoder Implementation Protocol:

The standard workflow for implementing masked autoencoders in single-cell genomics begins with data preprocessing, including normalization by library size, log transformation, and selection of highly variable genes. For the masking strategy, researchers typically employ random masking with a probability between 15-30%, though gene programme masking can be incorporated when prior biological knowledge is available.

The model architecture generally consists of a fully connected encoder with multiple hidden layers (typically 3-5 layers), a bottleneck layer representing the embedded space, and a symmetrical decoder structure. Training proceeds by forward-passing the masked input through the encoder to obtain cell representations, then through the decoder to reconstruct the original expression values. The loss function computes the difference between reconstructed and original expressions, focusing only on masked positions.

For downstream tasks, the pre-trained encoder can be used in several configurations: (1) Zero-shot evaluation where the frozen encoder produces embeddings for clustering or visualization; (2) Fine-tuning where the encoder is further trained on specific annotated tasks; or (3) Transfer learning where knowledge from large-scale datasets is transferred to smaller target datasets.

Contrastive Learning Implementation Protocol:

Contrastive learning implementation begins with similar preprocessing steps but places greater emphasis on data augmentation strategies. The standard workflow involves creating two augmented views for each cell in every training batch using transformations such as random masking (with different masking patterns), Gaussian noise addition, or more sophisticated approaches like the genetic crossover operation in CLEAR.

The model architecture typically employs twin neural networks (either with shared or momentum-updated weights) that process the augmented views. These networks project the inputs into a representation space where a contrastive loss function is applied. Popular contrastive losses include InfoNCE, which maximizes agreement between positive pairs relative to negative pairs, and Barlow Twins, which minimizes redundancy between embedding components while preserving information.

Training involves sampling a minibatch of cells, generating augmented views for each cell, computing embeddings through the encoder networks, and optimizing the contrastive objective. A critical consideration is the handling of negative pairs—some methods explicitly use different cells as negatives, while negative-pair-free methods like BYOL and Barlow Twins avoid this requirement through architectural innovations.

Technical Considerations and Implementation Guidelines

Paradigm Selection Framework

The choice between masked autoencoders and contrastive learning depends on several factors, including dataset characteristics, computational resources, and specific analytical goals. The following decision framework provides guidance for selecting the appropriate SSL paradigm:

Choose MASKED AUTOENCODERS when:

- Working with very large-scale datasets (>1 million cells) for pre-training

- Primary tasks involve gene expression reconstruction or generation

- Transfer learning from auxiliary datasets is a key objective

- Computational resources for training are substantial

- Capturing gene-gene interactions and correlations is prioritized

Choose CONTRASTIVE LEARNING when:

- Data integration and batch correction are primary concerns

- Identifying rare cell types is critical

- Working with multi-modal data (e.g., CITE-seq with RNA and protein)

- Computational resources are limited (faster convergence in some cases)

- Data sparsity and dropout events are severe concerns

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Recent benchmarking studies reveal several important trends in SSL for single-cell genomics. The scSSL-Bench comprehensive evaluation of 19 SSL methods across nine datasets and three downstream tasks indicates that specialized single-cell frameworks (scVI, CLAIRE) and foundation models (scGPT) excel at uni-modal batch correction, while generic SSL methods (VICReg, SimCLR) demonstrate superior performance in cell typing and multi-modal data integration [17].

Notably, random masking emerges as the most effective augmentation technique across all tasks, surpassing more complex domain-specific augmentations. This finding challenges the assumption that biologically-inspired augmentations necessarily yield better representations and suggests that simplicity and scalability may be more important factors in designing effective SSL strategies for single-cell data.

Another significant finding is that neither domain-specific batch normalization nor retaining the projector during inference consistently improves results, contradicting some earlier recommendations from computer vision. This highlights the importance of empirically validating architectural decisions rather than directly transferring practices from other domains.

Visual Summaries of Core Methodologies

Masked Autoencoder Workflow

Masked Autoencoder Methodology: This workflow illustrates the reconstruction-based learning approach of masked autoencoders, where portions of input data are masked and the model is trained to recover the original values.

Contrastive Learning Framework

Contrastive Learning Methodology: This diagram shows the comparative learning approach of contrastive methods, where augmented views of the same cell are brought closer in embedding space while different cells are pushed apart.

The convergence of masked autoencoders and contrastive learning represents a significant advancement in self-supervised learning for single-cell genomics. While both paradigms demonstrate substantial improvements over traditional supervised and unsupervised approaches, they exhibit complementary strengths and applications. Masked autoencoders excel in scenarios requiring transfer learning from large-scale auxiliary datasets and tasks involving reconstruction of gene expression patterns. Contrastive learning methods show superior performance in data integration, batch correction, and identification of rare cell populations. The emerging consensus from comprehensive benchmarking indicates that the optimal choice between these paradigms depends heavily on specific analytical goals, dataset characteristics, and computational constraints. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve toward increasingly multimodal assays and larger-scale atlases, both SSL approaches will play crucial roles in unlocking the biological insights contained within these complex datasets. Future methodological developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of both paradigms while addressing emerging challenges in scalability, interpretability, and integration of multimodal cellular measurements.

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) represent a transformative advancement in computational biology, leveraging large-scale pretraining and transformer architectures to interpret single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data. These models, inspired by breakthroughs in natural language processing, are trained on millions of single-cell transcriptomes through self-supervised learning to learn fundamental biological principles. By capturing complex gene-gene interactions and cellular states, scFMs provide a unified framework for a diverse range of downstream tasks, including cell type annotation, perturbation prediction, and data integration. This technical guide explores the core concepts, architectures, and methodologies underpinning scFMs, frames their development within the broader thesis of self-supervised learning for scRNA-seq research, and provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this rapidly evolving field.

The exponential growth of single-cell genomics data, with public repositories now containing tens of millions of single-cell datasets, has created both unprecedented opportunities and significant analytical challenges [18]. Traditional computational methods often struggle with the inherent technical noise, batch effects, and high dimensionality of scRNA-seq data, typically requiring specialized tools for each distinct analytical task. The field has increasingly recognized the limitations of this fragmented approach and the need for unified frameworks capable of integrating and comprehensively analyzing rapidly expanding data repositories [18].

In parallel, foundation models—large-scale deep learning models pretrained on vast datasets—have revolutionized data interpretation in natural language processing and computer vision through self-supervised learning [18]. These models develop rich internal representations that can be adapted to various downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning. The convergence of these two trends has catalyzed the emergence of single-cell foundation models (scFMs), which extend transformer-based architectures to single-cell analysis [18] [19].

The core premise of scFMs is that by exposing a model to millions of cells encompassing diverse tissues and conditions, the model can learn fundamental principles of cellular biology that generalize to new datasets and analytical tasks [18]. In these models, individual cells are treated analogously to sentences, while genes and their expression values serve as words or tokens [18] [19]. This conceptual framework enables the application of sophisticated neural architectures originally developed for language to the complex domain of transcriptional biology.

Key Concepts and Architectures of Single-Cell Foundation Models

Foundational Principles and Biological Analogies

Single-cell foundation models build upon several core principles that enable their remarkable adaptability and performance. The concept of self-supervised learning is fundamental, where models are pretrained on vast, unlabeled datasets using objectives that require the model to learn meaningful representations without human-provided labels [18] [4]. This approach is particularly valuable in single-cell genomics, where obtaining consistent, high-quality annotations across diverse datasets remains challenging.

The biological analogy framing cells as "sentences" and genes as "words" provides a powerful conceptual framework for adapting natural language processing techniques to transcriptomic data [18]. However, unlike words in a sentence, genes have no inherent sequential ordering, presenting unique computational challenges. Various strategies have been developed to address this, including ranking genes by expression levels within each cell or partitioning genes into expression bins to create deterministic sequences for model input [18].

Transformer Architectures in scFMs

Most scFMs utilize some variant of the transformer architecture, which employs attention mechanisms to learn and weight relationships between all pairs of input tokens [18]. This allows the model to determine which genes in a cell are most informative of cellular identity or state, and how they co-vary across different cellular contexts.

Table: Common Architectural Paradigms in Single-Cell Foundation Models

| Architecture Type | Key Characteristics | Example Models | Primary Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-based | Uses bidirectional attention; learns from all genes simultaneously | scBERT [18] | Effective for classification tasks and embedding generation |

| Decoder-based | Employs unidirectional masked self-attention; predicts genes iteratively | scGPT [18] [19] | Strong generative capabilities |

| Hybrid Designs | Combines encoder and decoder components | Various emerging models | Balance between classification and generation |

| Value Projection | Directly predicts raw gene expression values | scFoundation, CellFM [19] | Preserves full resolution of expression data |

The attention mechanism in transformer architectures enables scFMs to capture long-range dependencies and complex gene-gene interactions that might be missed by traditional statistical approaches. As these models process gene tokens through multiple transformer layers, they gradually build up latent representations at both the gene and cell levels, capturing hierarchical biological relationships [18].

Tokenization Strategies for Single-Cell Data

Tokenization—the process of converting raw gene expression data into discrete input units—is a critical consideration in scFM development. Unlike natural language, where words have established meanings and relationships, gene expression data presents unique challenges:

- Non-sequential nature: Genes lack inherent ordering, requiring artificial sequencing strategies [18]

- Continuous values: Expression levels are continuous measurements rather than discrete tokens

- High dimensionality: The ~20,000 human genes far exceed typical vocabulary sizes in language models

Common tokenization approaches include:

- Expression-based ranking: Ordering genes by expression magnitude within each cell [18]

- Value binning: Categorizing continuous expression values into discrete "buckets" [18] [19]

- Direct value projection: Preserving continuous values through linear projection [19]

Many models incorporate special tokens to represent metadata such as cell type, batch information, or experimental conditions, enabling the model to learn context-dependent representations [18]. Positional encoding schemes are adapted to represent the relative order or rank of each gene in the cell-specific sequence.

Pretraining Strategies and Self-Supervised Learning

Self-Supervised Learning Objectives

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a powerful framework for pretraining scFMs, enabling models to learn meaningful representations from vast unlabeled datasets [4]. The core idea of SSL is to define pretext tasks that allow the model to learn data intrinsic structures without human-provided labels. In single-cell genomics, several SSL approaches have demonstrated particular effectiveness:

Masked Autoencoding involves randomly masking a portion of the input gene expression values and training the model to reconstruct the original values based on the remaining context [4]. This approach forces the model to learn the underlying relationships between genes and their coordinated expression patterns. Variants include:

- Random masking: Masking random genes across the transcriptome

- Gene program masking: Masking biologically coherent sets of genes

- Isolated masking: Targeting specific functional gene categories

Contrastive Learning aims to learn representations by pulling similar cells closer together in the embedding space while pushing dissimilar cells apart [4] [2]. Methods like Bootstrap Your Own Latent (BYOL) and Barlow Twins have been adapted for single-cell data, using data augmentation strategies such as adding noise or simulating dropout events to create positive pairs [4].

Gene Ranking Prediction frames the pretext task as predicting the relative ranking of genes by expression level within each cell [19]. This approach leverages the observation that the relative ordering of highly expressed genes carries meaningful biological information about cell state and identity.

Large-Scale Data Curation for Pretraining

The performance of scFMs is heavily dependent on the scale and diversity of pretraining data. Recent models have been trained on increasingly massive datasets compiled from public repositories:

Table: Evolution of Single-Cell Foundation Model Scale

| Model | Pretraining Dataset Size | Model Parameters | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer [19] | 30 million cells | Not specified | Rank-based gene embeddings |

| scGPT [19] | 33 million cells | Not specified | Value categorization with attention masking |

| UCE [19] | 36 million cells | 650 million | Cross-species integration using protein language models |

| scFoundation [19] | ~50 million cells | ~100 million | Direct value prediction using masked autoencoding |

| CellFM [19] | 100 million human cells | 800 million | Modified RetNet framework for efficiency |

Data curation for scFM pretraining typically involves aggregating datasets from multiple sources including CELLxGENE, GEO, SRA, and specialized atlases like the Human Cell Atlas [18] [19]. This process requires careful quality control, gene name standardization, and normalization to address batch effects and technical variability across studies [18] [19]. The resulting pretraining corpora aim to capture a comprehensive spectrum of biological variation across tissues, conditions, and experimental platforms.

Efficiency Considerations and Model Optimization

Training scFMs on hundreds of millions of cells requires sophisticated computational strategies to manage memory and processing requirements. Several approaches have emerged to address these challenges:

Linear Complexity Architectures: Models like CellFM employ modified transformer architectures such as RetNet that reduce the computational complexity from quadratic to linear with respect to sequence length, enabling more efficient processing of long gene sequences [19].

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA): This technique reduces the number of trainable parameters during fine-tuning by injecting trainable rank decomposition matrices into transformer layers, making adaptation to new tasks more computationally efficient [19].

Gradient Checkpointing and Mixed Precision: These standard deep learning optimization techniques are particularly valuable for scFMs, allowing larger models to fit within memory constraints while maintaining numerical stability [19].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating scFM performance across diverse biological applications. Recent studies have established comprehensive evaluation frameworks assessing models on multiple criteria [20]:

Data Property Estimation measures how well simulated data matches real experimental data across 13 distinct criteria including mean-variance relationships, dropout rates, and correlation structures [21].

Biological Signal Retention assesses the preservation of differentially expressed genes, differentially variable genes, and other meaningful biological patterns in model outputs [21].

Computational Scalability evaluates runtime and memory consumption with respect to dataset size, acknowledging the trade-offs between model complexity and practical utility [21].

Application-Specific Performance tests model capabilities on concrete biological tasks including cell type annotation, batch integration, perturbation prediction, and gene function analysis [20].

Performance Across Downstream Tasks

Comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal that no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, emphasizing the importance of task-specific model selection [20]. However, several general patterns have emerged:

Cell Type Annotation: scFMs demonstrate strong performance in cell type identification, particularly for rare cell populations and in transfer learning scenarios where models pretrained on large datasets are applied to smaller target datasets [4] [20]. The macro F1 score improvements from 0.7013 to 0.7466 in PBMC datasets and from 0.2722 to 0.3085 in Tabula Sapiens datasets highlight the value of large-scale pretraining [4].

Batch Integration: scFMs show remarkable capability in removing technical batch effects while preserving biological variation, outperforming traditional methods like Harmony and Seurat in challenging integration scenarios involving multiple tissues, species, and experimental platforms [20].

Perturbation Prediction: Models like Geneformer and scGPT demonstrate emergent capability in predicting cellular responses to genetic and chemical perturbations, with performance linked to the model's ability to capture gene-regulatory relationships during pretraining [19] [20].

Zero-Shot Learning: Several scFMs exhibit promising zero-shot capabilities, where models can perform tasks like cell type annotation without task-specific fine-tuning, suggesting that meaningful biological knowledge is encoded during pretraining [4] [20].

Novel Evaluation Metrics

Recent benchmarking efforts have introduced biologically-informed evaluation metrics that move beyond technical performance to assess how well models capture biological ground truth:

scGraph-OntoRWR measures the consistency of cell type relationships captured by scFMs with established biological knowledge encoded in cell ontologies, providing a knowledge-aware assessment of representation quality [20].

Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD) quantifies the ontological proximity between misclassified cell types, offering a biologically nuanced perspective on classification errors that acknowledges the severity of different error types [20].

Roughness Index (ROGI) evaluates the smoothness of the cell-property landscape in the latent space, with smoother landscapes correlating with better downstream task performance and easier model fine-tuning [20].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Foundation Model Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Platforms | Primary Function | Relevance to scFM Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | CELLxGENE [18], GEO [19], SRA [18], Human Cell Atlas [18] | Provide standardized, annotated single-cell datasets | Source of large-scale pretraining data and benchmark evaluation datasets |

| Processing Frameworks | Scanpy [22], Seurat [22], scvi-tools [22] | Data preprocessing, normalization, and basic analysis | Essential for data curation, quality control, and preprocessing before model training |

| Model Architectures | Transformer variants [18], RetNet [19], ERetNet [19] | Neural network backbones for foundation models | Core architectural components enabling efficient large-scale pretraining |

| Training Frameworks | PyTorch, MindSpore [19], TensorFlow | Deep learning development ecosystems | Provide optimized environments for distributed training and inference |

| Benchmarking Tools | SimBench [21], specialized evaluation pipelines [20] | Standardized performance assessment | Critical for rigorous comparison of different models and approaches |

| Visualization Platforms | CELLxGENE Explorer [23], integrated UMAP/t-SNE | Interactive data exploration and model output inspection | Enable interpretation of model representations and biological discovery |

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite rapid progress, several significant challenges remain in the development and application of single-cell foundation models. Interpretability of model predictions and representations continues to be a hurdle, with the biological relevance of latent embeddings often difficult to ascertain [18]. Computational intensity for training and fine-tuning these large models limits accessibility for researchers without substantial computational resources [18]. The non-sequential nature of omics data continues to pose architectural challenges, as transformers were originally designed for sequential data [18]. Additionally, issues of data quality inconsistency across studies and batch effects persist despite advances in integration methods [18].

Promising future directions include the development of multimodal foundation models that integrate transcriptomic, epigenetic, proteomic, and spatial data [23]. Approaches like CellWhisperer demonstrate the potential for natural language integration, enabling researchers to query data using biological concepts rather than computational syntax [23]. There is also growing interest in specialized efficient architectures that maintain performance while reducing computational requirements, and improved interpretation tools that bridge the gap between model representations and biological mechanism.

The trajectory of single-cell foundation models suggests a future where researchers can interact with complex biological data through intuitive interfaces, ask biologically meaningful questions in natural language, and receive insights grounded in comprehensive analysis of the entire research corpus. As these models continue to evolve, they hold the potential to dramatically accelerate biological discovery and therapeutic development.

SSL Versus Traditional Supervised and Unsupervised Methods in scRNA-seq Analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the profiling of gene expression at the level of individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity and complex biological processes that are often obscured in bulk sequencing approaches [24] [10]. The technology has rapidly evolved since its inception in 2009, generating increasingly large and complex datasets that present significant computational challenges for analysis and interpretation [24] [25]. The emergence of scRNA-seq as a big-data domain has shifted the analytical focus from interpreting isolated datasets to understanding data within the context of existing atlases comprising millions of cells [4].

Within this context, machine learning approaches have become indispensable tools for extracting meaningful biological insights from high-dimensional scRNA-seq data. Traditional supervised and unsupervised learning methods have established foundational capabilities for cell type classification and pattern discovery. More recently, self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative approach that leverages unlabeled data to learn rich representations, showing particular promise in scenarios with limited labeled data or requiring transfer learning across datasets [4]. This technical review examines the comparative advantages, limitations, and optimal application contexts of SSL relative to traditional supervised and unsupervised methods in scRNA-seq analysis, framed within the broader thesis that SSL represents a paradigm shift in computational biology for harnessing the full potential of large-scale genomic data.

Fundamentals of scRNA-seq and Machine Learning Approaches

scRNA-seq Technology and Data Characteristics

Single-cell RNA sequencing technology enables high-resolution dissection of transcriptional heterogeneity by capturing the transcriptome of individual cells. The core workflow involves single-cell isolation, cell lysis, reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA, amplification, and library preparation followed by sequencing [24] [26]. A critical advancement was the introduction of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) which tag individual mRNA molecules to mitigate amplification biases and enhance quantitative accuracy [24] [26].

Unlike bulk RNA sequencing that measures average gene expression across cell populations, scRNA-seq reveals the distinct transcriptional profiles of individual cells, enabling identification of rare cell types, developmental trajectories, and stochastic gene expression patterns [10]. However, this granularity comes with computational challenges including high dimensionality, technical noise, sparsity, and batch effects that complicate analysis [26] [25].

Machine Learning Paradigms in scRNA-seq Analysis

Table 1: Machine Learning Paradigms in scRNA-seq Analysis

| Learning Paradigm | Data Requirements | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Labeled data (e.g., cell type annotations) | Cell-type classification, Disease state prediction | High performance on specific tasks with sufficient labels | Direct optimization for predictive accuracy |

| Unsupervised Learning | Unlabeled data only | Clustering, Dimensionality reduction, Trajectory inference | Discovers novel patterns without prior knowledge | No need for expensive annotations |

| Self-Supervised Learning | Primarily unlabeled data with optional fine-tuning on labels | Representation learning, Transfer learning, Multi-task analysis | Leverages large unlabeled datasets, Generalizable representations | Excels in low-label environments |

Supervised learning approaches rely on labeled data to train models for prediction tasks such as cell-type classification. These methods typically require high-quality annotations which can be scarce or inconsistent across datasets [4] [25]. Traditional supervised methods include support vector machines (SVM) and random forests, with more recent deep learning architectures achieving state-of-the-art performance on well-annotated datasets [25].

Unsupervised learning methods operate without labeled data to discover intrinsic patterns in scRNA-seq data. Principal component analysis (PCA), t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) are widely used for dimensionality reduction and visualization, while clustering algorithms identify putative cell types and states [25]. These methods are invaluable for exploratory analysis but may not optimize representations for specific downstream tasks.

Self-supervised learning represents an intermediate approach that creates supervisory signals from the intrinsic structure of unlabeled data. Through pretext tasks such as masked autoencoding or contrastive learning, SSL models learn generalized representations that can be fine-tuned for various downstream applications with minimal labeled data [4]. This approach is particularly well-suited to scRNA-seq data due to the abundance of unlabeled datasets and the cost of expert annotation.

Self-Supervised Learning Approaches: Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

SSL Framework Architectures for scRNA-seq

Self-supervised learning frameworks for scRNA-seq typically employ a two-stage approach consisting of pre-training on large unlabeled datasets followed by optional fine-tuning on specific downstream tasks [4]. The pre-training stage employs pretext tasks that leverage the inherent structure of gene expression data to learn meaningful representations without manual labels.

Masked Autoencoders (MAEs) have demonstrated particularly strong performance in scRNA-seq applications [4]. These models randomly mask portions of the input gene expression vector and train the network to reconstruct the masked values based on the unmasked context. This approach forces the model to learn interdependencies and co-expression patterns among genes. Advanced masking strategies include:

- Random masking: Uniform random selection of genes to mask, introducing minimal inductive bias

- Gene programme masking: Masking biologically defined gene sets with coordinated functions

- Isolated masking: Targeting specific functional gene categories such as transcription factors

Contrastive learning methods such as Bootstrap Your Own Latent (BYOL) and Barlow Twins learn representations by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same cell while distinguishing it from other cells [4]. These approaches have shown value in scRNA-seq, though recent evidence suggests masked autoencoders may outperform them in genomic applications [4].

Figure 1: SSL Workflow for scRNA-seq Analysis. The diagram illustrates the two-stage self-supervised learning framework with pre-training on large unlabeled datasets followed by zero-shot evaluation or fine-tuning for specific downstream applications.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies have evaluated SSL performance across multiple scRNA-seq datasets and downstream tasks. A comprehensive study published in Nature Machine Intelligence examined SSL methods trained on over 20 million cells from the CELLxGENE census dataset, assessing performance across cell-type prediction, gene-expression reconstruction, cross-modality prediction, and data integration tasks [4].

The experimental protocol involved:

Pre-training Dataset: Models were trained on the scTab dataset comprising approximately 20 million cells and 19,331 human protein-encoding genes to ensure broad coverage for analyzing unseen datasets [4].

Model Architectures: Fully connected autoencoder networks were selected as the base architecture due to their ubiquitous application in SCG tasks, providing a standardized framework for comparing SSL approaches while minimizing architectural confounding factors [4].

Evaluation Datasets: Performance was assessed on three biologically diverse datasets:

- Human Lung Cell Atlas (HLCA): 2,282,447 cells, 51 cell types

- Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) post SARS-CoV-2 infection: 422,220 cells, 30 cell types

- Tabula Sapiens Atlas: 483,152 cells, 161 cell types [4]

Evaluation Metrics:

- Cell-type prediction: Macro F1 score (robust to class imbalance) and micro F1 score

- Gene-expression reconstruction: Weighted explained variance

Table 2: SSL Performance on Cell-Type Prediction Tasks

| Dataset | Baseline Method | SSL Approach | Performance Gain | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC (SARS-CoV-2) | Supervised Learning | SSL with Pre-training | 0.7013 to 0.7466 macro F1 | Notable improvement for underrepresented cell types |

| Tabula Sapiens | Supervised Learning | SSL with Pre-training | 0.2722 to 0.3085 macro F1 | Correct classification of 6,881/7,717 type II pneumocytes (vs. 2,441 baseline) |

| HLCA | Supervised Learning | SSL with Pre-training | Marginal improvement | Rich dataset with less transfer benefit |

Comparative Analysis: SSL Versus Traditional Methods

Performance Advantages and Limitations