Leveraging Support Vector Machines (SVM) for Precise Single-Cell Classification: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Support Vector Machine (SVM) applications in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data classification, a critical task for elucidating cellular heterogeneity.

Leveraging Support Vector Machines (SVM) for Precise Single-Cell Classification: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Support Vector Machine (SVM) applications in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data classification, a critical task for elucidating cellular heterogeneity. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational role of SVM in cell type annotation, detail methodological workflows for robust model implementation, and address key challenges like data uncertainty and batch effects. The content is validated through comparative benchmarking against other machine learning techniques, highlighting SVM's consistent top-tier performance. By synthesizing current trends and future directions, this guide serves as a strategic resource for advancing precision medicine and accelerating therapeutic discovery.

The Foundational Role of SVM in Decoding Single-Cell Heterogeneity

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a revolutionary advancement in transcriptomic analysis, enabling researchers to decode gene expression profiles at the resolution of individual cells rather than population averages [1]. This technology has fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular heterogeneity in complex biological systems, revealing unique cellular behaviors and functions that are masked in bulk RNA-seq approaches [2] [1].

The scRNA-seq workflow encompasses several critical steps, beginning with the isolation of viable single cells from tissues, followed by cell lysis, reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library preparation [1]. Since its initial development in 2009, numerous scRNA-seq protocols have emerged, broadly categorized into full-length transcript methods (e.g., Smart-Seq2, MATQ-Seq) and 3'/5' end counting protocols (e.g., Drop-Seq, inDrop) [1]. Each approach offers distinct advantages in throughput, cost, and application specificity, with droplet-based methods typically enabling higher throughput at lower cost per cell [1].

The Critical Role of Cell Classification in scRNA-seq Analysis

Accurate cell type identification and classification represents a fundamental challenge and necessity in scRNA-seq analysis. As machine learning expert Mehrtash Babadi notes, determining cell identity is "one of the first steps for researchers in studying and analyzing single cells," yet this process "can take days or even weeks, depending on the number of cells being labeled, and requires labor-intensive literature and database searches" [3].

Traditional cell annotation methods rely heavily on manual interpretation of marker genes, introducing subjectivity and limiting scalability as datasets grow to encompass millions of cells [4]. The critical need for accurate, automated classification is particularly evident in clinical and drug development contexts, where misclassification can lead to incorrect biological conclusions, flawed diagnostic markers, or ineffective therapeutic targets [5].

Machine learning approaches have emerged as powerful solutions to this challenge, enabling automated, high-dimensional pattern recognition that can identify cell types and states with unprecedented accuracy and consistency [5]. These computational strategies are becoming increasingly essential as single-cell technologies scale to profile millions of cells simultaneously [6].

Support Vector Machines for Single-Cell Classification

SVM Fundamentals and Biological Relevance

Support Vector Machine (SVM) learning represents a powerful classification approach that has demonstrated particular utility for single-cell transcriptomics [7] [5]. As a supervised machine learning method, SVM constructs an optimal hyperplane to separate different cell types in high-dimensional gene expression space, oriented to maximize the margin between the closest data points of each class [7].

The mathematical foundation of SVM makes it exceptionally well-suited to single-cell data, which typically exhibits high dimensionality (thousands of genes) relative to sample size [7]. SVM's capacity to recognize subtle patterns in complex datasets enables it to distinguish closely related cell subtypes that may differ in only a handful of transcripts [7]. Furthermore, kernel methods allow SVM to handle non-linear relationships in gene expression data by implicitly mapping inputs to higher-dimensional feature spaces [7].

ActiveSVM for Minimal Gene Set Discovery

The ActiveSVM methodology represents a significant innovation in feature selection for single-cell classification [8]. This active learning approach identifies minimal but highly informative gene sets that enable accurate cell type identification using a small fraction of the total transcriptome [8].

The algorithm begins with an empty gene set and iteratively selects genes through a classification task, focusing computational resources on poorly classified cells [8]. At each iteration, ActiveSVM applies the current gene set to classify cells into predefined types, identifies misclassified cells, and selects maximally informative genes to improve classification accuracy [8]. This active sampling strategy enables the method to scale to datasets with over one million cells while maintaining computational efficiency [8].

Table 1: Performance of ActiveSVM on Representative Single-Cell Datasets

| Dataset | Cell Types | Cells | Minimal Gene Set | Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human PBMCs [8] | 5 | 10,194 | 15 genes | >85% |

| Tabula Muris [8] | 55 | N/A | <150 genes | ~90% |

| Mouse Brain [8] | Multiple | 1.3 million | N/A | High accuracy with substantial cost reduction |

Experimental Protocols for SVM-Based Cell Classification

Sample Preparation and scRNA-seq Protocol Selection

The initial stage involves careful sample preparation and selection of appropriate scRNA-seq protocols based on research objectives [1]. The following table summarizes key protocol considerations:

Table 2: Comparison of Representative scRNA-seq Protocols

| Protocol | Isolation Strategy | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Amplification Method | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 [1] | FACS | Full-length | No | PCR | Enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts |

| Drop-Seq [1] | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | High-throughput, low cost per cell |

| inDrop [1] | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | IVT | Uses hydrogel beads; efficient barcode capture |

| Seq-well [1] | Droplet-based | 3'-only | Yes | PCR | Portable, low-cost implementation |

| MATQ-Seq [1] | Droplet-based | Full-length | Yes | PCR | Increased accuracy in quantifying transcripts |

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Quality control is essential to remove technical artifacts and ensure reliable classification [1]. Critical steps include:

- Cell filtering: Remove low-quality cells and empty droplets using tools like EmptyDrops [9]

- Doublet detection: Identify multiple cells mistakenly grouped as one using DoubletFinder [9]

- Normalization: Apply scRNA-seq specific normalization to address technical variability [9]

- Batch effect correction: Address technical variations between experimental batches using integration methods [9]

ActiveSVM Implementation for Feature Selection

The ActiveSVM protocol involves the following key steps [8]:

- Data Partitioning: Split dataset into training (80%) and test (20%) sets

- Label Definition: Establish cell type labels through unsupervised clustering or experimental metadata

- Iterative Gene Selection:

- Begin with empty gene set

- Train SVM classifier with current gene set

- Identify misclassified cells

- Select genes that maximally rotate the SVM margin to improve classification

- Repeat until target accuracy is achieved

- Validation: Assess performance on held-out test set

The algorithm provides min-complexity and min-cell versions to optimize for different computational constraints [8].

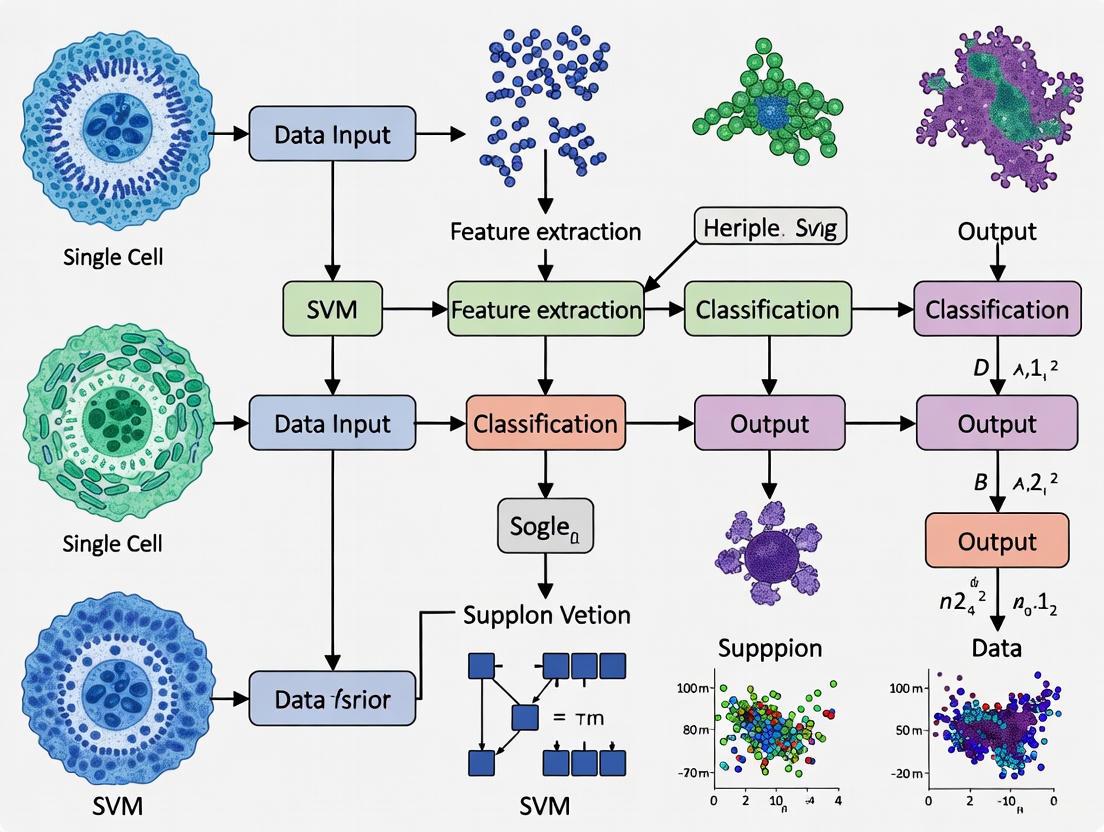

Workflow for SVM-Based Single-Cell Classification

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for SVM-Based scRNA-seq Analysis

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Single-cell isolation reagents (FACS, microfluidics) | Separation of individual cells from tissue matrix |

| Cell lysis buffers | Release of RNA while maintaining integrity | |

| Poly[T]-primers | Selective capture of polyadenylated mRNA | |

| Reverse transcription enzymes | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Correction for amplification bias and quantification | |

| Library preparation kits | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries | |

| Computational Tools | Seurat [9] | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis platform |

| Cell Annotation Service (CAS) [3] | Machine learning-based cell type annotation | |

| ActiveSVM implementation [8] | Minimal gene set discovery for classification | |

| Scanpy [5] | Python-based single-cell analysis toolkit | |

| CellAnnotator [4] | AI-powered annotation using language models |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

SVM-based classification has demonstrated significant utility across diverse biological applications. In cancer genomics, SVM enables molecular subtyping of tumors based on single-cell profiles, revealing intra-tumor heterogeneity with clinical implications [7]. In immunology, SVM classifiers can distinguish closely related immune cell states in PBMCs, identifying both canonical markers and novel genes associated with cell identity [8].

The integration of SVM with emerging technologies represents a promising future direction. Spatial transcriptomics benefits from SVM classification to map cell types within tissue architecture [8]. Multi-modal single-cell data, including epigenomic and proteomic measurements, can be incorporated into kernel functions to enhance classification accuracy [5].

As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, producing increasingly large and complex datasets, SVM and related machine learning approaches will play an indispensable role in extracting biologically meaningful patterns from transcriptional heterogeneity [5]. The development of more interpretable, robust, and generalizable classification models remains an active area of research with significant potential for advancing both basic biology and translational applications [5].

SVM Classification Mechanism for Cell Types

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) represent a class of supervised machine learning algorithms that have demonstrated exceptional performance in the analysis of high-dimensional biological data, particularly in the field of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Their core principle revolves around finding the optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between different classes of cells, providing a robust framework for cell type identification and classification [10]. In single-cell research, where data is characterized by high dimensionality and inherent noise, SVMs offer resilience to overfitting and the ability to handle complex, non-linear relationships through the kernel trick [11] [12]. This makes them particularly well-suited for distinguishing closely related cell populations based on their transcriptional profiles, a common challenge in modern biomedical research.

The application of SVM-based methods has become increasingly prevalent in single-cell studies, with tools such as scPred, scAnnotatR, and scHPL leveraging these algorithms to accurately classify cell types and states [13] [14] [15]. These methods enable researchers to move beyond manual, cluster-based annotation approaches, which are time-consuming and subjective, toward automated, reproducible classification systems that can integrate information across multiple datasets and continuously learn from new data [14] [15]. This technical advancement is crucial for building comprehensive cell atlases and for the early diagnosis of diseases through precise cell state identification.

Core Principles of SVM

Maximum Margin Classification

The foundational concept of SVM is the maximum margin classifier. For a linearly separable dataset, the algorithm seeks the hyperplane that not only separates the classes but also maximizes the distance (margin) to the nearest data points of any class [10] [16]. This optimal separating hyperplane is defined by the equation wᵀx + b = 0, where w is the normal vector to the hyperplane and b is the bias term [10].

The margin, γ, is the perpendicular distance from the hyperplane to the closest data points, known as the support vectors [16]. The optimization objective is to find the parameters w and b that maximize this margin. This is formulated as the following optimization problem:

minimize{w,b} ½||w||² subject to yi(wᵀx_i + b) ≥ 1 for all i = 1, 2, ..., m [10] [16]

The constraints ensure that all data points are correctly classified and lie outside the margin. The support vectors, which satisfy yi(wᵀxi + b) = 1, are the critical elements of the dataset that ultimately determine the position and orientation of the hyperplane [16]. The maximum margin approach enhances the model's generalization performance, as it is less sensitive to noise in the training data and reduces the risk of overfitting [17].

Soft Margin and Regularization

Biological data, including scRNA-seq data, is often not perfectly linearly separable due to noise, outliers, or inherent class overlap. To handle such scenarios, SVMs incorporate a soft margin approach [10] [18]. This modification allows some data points to violate the margin constraints by introducing slack variables (ξ_i) [10].

The optimization problem then becomes:

minimize{w,b} ½||w||² + C Σξi subject to yi(wᵀxi + b) ≥ 1 - ξi and ξi ≥ 0 for all i [10] [16]

The regularization parameter C controls the trade-off between maximizing the margin and minimizing the classification error [10] [17]. A small C value emphasizes a wider margin, potentially accepting more training errors (higher bias, lower variance), while a large C imposes a stricter penalty for errors, resulting in a narrower margin that fits the training data more closely (lower bias, higher variance) [17]. The hinge loss function, defined as max(0, 1 - yi(wᵀxi + b)), is commonly used to quantify the penalty for misclassifications or margin violations [10] [18].

The Kernel Trick for Non-Linear Data

A powerful extension to linear SVMs is the kernel trick, which enables the algorithm to find non-linear decision boundaries by implicitly mapping the original input features into a higher-dimensional space where the data becomes linearly separable [10] [12] [18]. This avoids the computational expense of explicitly computing the coordinates in the high-dimensional space.

A kernel function is defined as K(x, x') = φ(x)ᵀφ(x'), where φ is the mapping function [12]. The kernel computes the similarity between two data points x and x' in the transformed feature space. Common kernel functions used in biological applications include:

Table 1: Major Kernel Functions in Support Vector Machines

| Kernel Type | Mathematical Formula | Key Characteristics | Typical Use Cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Kernel | K(x, x') = xᵀx' [12] | Fast training, interpretable boundaries, dot product similarity [12] | Linearly separable data, text classification [12] | ||||

| Polynomial Kernel | K(x, x') = (xᵀx' + r)ᵈ [12] | Captures feature interactions, degree (d) controls curvature, risk of overfitting [12] | Mildly non-linear data, curved trends [12] | ||||

| RBF (Gaussian) Kernel | K(x, x') = exp(-γ | x - x' | ²) [12] | Distance-based similarity, highly flexible, gamma (γ) controls influence spread [12] | Complex shapes, unknown data patterns, default choice for non-linear data [12] | ||

| Sigmoid Kernel | K(x, x') = tanh(γ xᵀx' + r) [12] | Neural network-inspired, behaves like activation function, parameter sensitivity [12] | Problems with smooth thresholding behavior [12] |

In the dual formulation of the SVM optimization problem, the data appears only within inner products, which can be replaced by the kernel function K(xi, xj) [10]. The dual objective function is:

maximizeα Σαi - ½ ΣΣ αi αj yi yj K(xi, xj) subject to 0 ≤ αi ≤ C and Σαi y_i = 0 [10]

The decision function for a new test point x then becomes: f(x) = sign( Σαi yi K(x_i, x) + b ) [10]. For single-cell RNA-seq data, linear kernels have been found to outperform more sophisticated kernels in several benchmarks, making them a suitable starting point for cell classification tasks [14].

SVM Applications in Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing

Cell Type Identification and Classification

The primary application of SVMs in scRNA-seq analysis is the automatic identification of cell types. This process typically involves training an SVM classifier on a reference dataset with known cell labels and then applying the model to predict labels for cells in a new, unlabeled dataset [13] [14]. This supervised approach overcomes the limitations of manual clustering and annotation, which is subjective, time-consuming, and difficult to reproduce across studies [14].

scPred is a method that uses a combination of unbiased feature selection from a reduced-dimension space (like principal components) and SVM for prediction [13]. It provides highly accurate classification of individual cells and includes a rejection option whereby cells are labeled as "unassigned" if the conditional class probability is lower than a defined threshold (e.g., 0.9) [13]. This avoids misclassifying cells from types not present in the training model. In one application, scPred was used to distinguish tumor from non-tumor epithelial cells in gastric cancer data, achieving a sensitivity of 0.979 and a specificity of 0.974, outperforming models trained on differentially expressed genes alone [13].

scAnnotatR is another R/Bioconductor package that uses pre-trained SVM classifiers organized in a hierarchical tree-like structure [14]. This architecture allows for more accurate classification of closely related cell types. For instance, a parent classifier can first identify general "B cells," and then a child classifier can distinguish terminally differentiated "plasma cells" within that population [14]. This hierarchical approach increases accuracy by using features best suited to differentiate subtypes.

Table 2: Performance of SVM-Based Classification in Single-Cell Studies

| Study / Method | Application Context | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| scPred [13] | Classifying tumor vs. non-tumor epithelial cells in gastric cancer | Sensitivity: 0.979, Specificity: 0.974, AUROC: 0.999, F1 score: 0.990 | Showed higher performance than using differentially expressed genes as features |

| scAnnotatR [14] | General cell type classification across multiple tissues and systems | Ranked among the best performing tools in accuracy; able to process datasets with >600,000 cells | Hierarchical SVM structure improved accuracy; linear kernels performed best |

| scHPL (Linear SVM) [15] | Hierarchical classification on simulated data, PBMCs, and a complex brain dataset (92 cell types) | HF1-score ~0.99 (simulated), >0.9 (real data) | Linear SVM consistently showed higher classification accuracy than a one-class SVM alternative |

Hierarchical and Progressive Learning

Cell types exist in natural hierarchies (e.g., Immune cells → T cells → CD4+ T cells → T helper subsets). Hierarchical classification exploits this structure by dividing the overall classification problem into smaller, simpler sub-problems [14] [15]. Tools like scAnnotatR and scHPL (Hierarchical Progressive Learning) implement this concept using SVMs.

scHPL enables continuous learning from multiple scRNA-seq datasets, which are often annotated at different resolutions [15]. It learns and updates a classification tree by matching cell populations across datasets, handling scenarios such as perfect matches, merging, or splitting of populations [15]. This progressive learning allows the model to integrate new datasets and cell types without forgetting previously learned knowledge, mimicking a continuous learning process.

Detection of Novel Cell Types and Population Drift

A significant challenge in supervised classification is handling cell types that are not represented in the training data. SVM-based approaches address this with rejection options. A common method is to set a threshold on the prediction probability; if the maximum probability for all classes is below the threshold, the cell is "unassigned" or "rejected" [13] [15].

For more robust detection of novel cell populations, one-class SVMs can be employed. Unlike traditional SVMs that find a boundary between classes, a one-class SVM learns a tight decision boundary around a single class, identifying whether a new data point belongs to that class or is an outlier [15]. scHPL, for example, uses a two-step rejection process: first, it calculates the reconstruction error after PCA (where novel cell types will have high error), and second, it can employ a one-class SVM for final classification and rejection [15]. While one-class SVMs provide a sophisticated rejection mechanism, benchmarks show that linear SVMs generally achieve higher classification accuracy for known cell types [15].

Furthermore, one-class SVMs have been proposed for detecting population drift in deployed machine learning models for medical diagnostics [19]. Population drift occurs when the data distribution of input features changes between the training phase and real-world deployment, potentially degrading model performance [19]. A one-class SVM trained on the original data can monitor new patient data and detect distribution shifts, serving as an early warning system for model retraining [19].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Building a Cell Type Classifier with scPred

This protocol outlines the steps to train a cell type classifier using the scPred method for distinguishing between two cell states (e.g., tumor vs. non-tumor) [13].

Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Obtain a labeled scRNA-seq dataset as a training set. The labels should be binary (e.g., Tumor, Non-Tumor).

- Perform standard scRNA-seq preprocessing: quality control, normalization, and scaling.

- Conduct feature selection. scPred performs unbiased feature selection from a reduced-dimension space (e.g., principal components). Alternatively, you may use highly variable genes.

Model Training:

- Train a Support Vector Classifier (e.g., using

SVCfromscikit-learnin Python or thecaretpackage in R) with a linear kernel. - Set the regularization parameter

C(default=1 is a good start). The model is trained to separate one class versus all others. - The output is a trained model that has learned the hyperplane and the associated support vectors.

- Train a Support Vector Classifier (e.g., using

Model Application and Prediction:

- Apply the trained model to a held-out test set or a new, independent dataset.

- For each cell, the model outputs a conditional class probability, Pr(y=1|f), of belonging to the target class.

- Rejection Option: Set a probability threshold (e.g., 0.9). Cells with a maximum probability below this threshold for any class are labeled as "unassigned."

Validation:

- Validate predictions using an independent gold-standard method, such as immunohistochemistry for specific protein markers [13].

- Calculate performance metrics: sensitivity, specificity, AUROC, and F1 score.

Protocol: Hierarchical Classification with scAnnotatR/scHPL

This protocol describes a hierarchical classification strategy for annotating cells at multiple levels of resolution [14] [15].

Define the Cell Type Hierarchy:

- Establish a tree structure representing the biological relationships between cell types. For example:

- Root: All Cells

- Level 1: Immune Cells, Stromal Cells, Epithelial Cells

- Level 2 (under Immune Cells): T cells, B cells, Myeloid cells

- Level 3 (under T cells): CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells

- Establish a tree structure representing the biological relationships between cell types. For example:

Train Parent and Child Classifiers:

- For each non-leaf node in the tree (e.g., "T cells"), train a binary SVM classifier to distinguish that cell type from all others at the same hierarchy level.

- Use the feature selection and training procedure as in the scPred protocol.

- A cell must first be classified as an "Immune Cell" by the parent classifier before it can be passed down to the "T cell" vs. "B cell" classifier.

Progressive Learning (for scHPL):

- To integrate a new labeled dataset, train a flat classifier on it.

- Use cross-prediction between the new dataset and the existing tree to match labels.

- Update the classification tree based on the matching results, which may involve adding new branches (new cell types) or splitting/merging existing ones.

Classification with Rejection:

- Classify cells from a new dataset by propagating them down the tree.

- Implement a rejection at each node based on reconstruction error from PCA and/or the output of a one-class SVM [15].

- Cells that are rejected at a node are assigned the label of that node (the parent class) and are not classified further.

Visualization of SVM Workflows in Single-Cell Analysis

SVM Classification Workflow for Single-Cell Data

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end process of applying SVM for cell type classification, from data preparation to model evaluation.

SVM Classification Workflow for scRNA-seq Data

Hierarchical SVM Classification Tree

This diagram depicts the tree-like structure of a hierarchical SVM classifier, as used in methods like scAnnotatR and scHPL.

Hierarchical SVM Classification Tree

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources for SVM-based Single-Cell Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Function in Analysis | Relevant Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| scPred [13] | R Package | Uses SVM for accurate single-cell classification; provides a rejection option for unknown cells. | Binary classification of cell states (e.g., tumor vs. non-tumor). |

| scAnnotatR [14] | R/Bioconductor Package | Provides a framework for classification using pre-trained, hierarchically organized SVM models. | Classifying cells into a known hierarchy of types with high accuracy and scalability. |

| scHPL [15] | Python Method | Implements hierarchical progressive learning with SVM to continuously learn from new datasets. | Integrating multiple datasets annotated at different resolutions and updating a classification tree. |

| Caret [14] | R Package | A unified interface for training and evaluating multiple classification models, including SVMs. | General model training and tuning; used internally by scAnnotatR. |

| Scikit-learn [10] | Python Library | Provides implementations of SVM (SVC) with various kernels and regularization parameters. | Building custom SVM classification pipelines in Python. |

| Linear Kernel [12] [14] | Algorithm | The default and often best-performing kernel for scRNA-seq data due to high dimensionality. | Most cell classification tasks, as a starting point. |

| One-class SVM [15] | Algorithm | Learns a decision boundary around a single class to detect outliers or novel cell types. | Detecting cell populations not present in the training data (population drift or novel types). |

The integration of machine learning (ML) with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our capacity to decipher cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues [5]. This technological synergy enables researchers to move beyond traditional bulk analysis to examine gene expression profiles at the individual cell level, uncovering previously inaccessible biological insights. Among ML techniques, Support Vector Machines (SVM) have emerged as a powerful tool for single-cell classification tasks, particularly due to their ability to handle high-dimensional data and identify optimal separating hyperplanes in complex feature spaces [20]. The application of SVM within single-cell research spans from fundamental cell type annotation to the sensitive detection of rare cell populations that play critical roles in development, disease progression, and treatment response [5] [21].

This application note outlines key methodologies and protocols for implementing SVM and related ML approaches in single-cell research, with particular emphasis on addressing the computational challenges inherent to scRNA-seq data, including high dimensionality, technical noise, and class imbalance [22] [23]. We provide structured frameworks for experimental design, data processing, and analysis to ensure robust, reproducible results across diverse research applications.

Core Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Support Vector Machine Fundamentals for Single-Cell Data

Support Vector Machines operate by identifying the optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between different cell classes in a high-dimensional feature space [20]. For single-cell applications, this feature space typically consists of gene expression values, with each gene representing a dimension. The effectiveness of SVM in scRNA-seq analysis stems from several intrinsic advantages: capacity to handle high-dimensional data, robustness to noise through regularization parameters, and flexibility via kernel functions that enable capture of complex, non-linear relationships between cell types [20].

A critical consideration for single-cell applications is SVM's performance in multi-class classification, which can be achieved through strategies such as one-versus-one or one-versus-rest approaches. Studies benchmarking ML classifiers for granular cell type identification have demonstrated that SVM, along with other methods including Random Forest and logistic regression, achieves high accuracy when combined with appropriate feature selection techniques [20]. The kernel trick allows SVM to efficiently operate in transformed feature spaces without explicitly computing coordinates, making it particularly valuable for capturing complex gene expression patterns that distinguish closely related cell types.

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Classifiers

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Classifiers for Single-Cell Data

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Optimal Use Cases | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; Memory efficient; Versatile via kernel functions | Less effective with highly imbalanced data; Requires careful parameter tuning | Cell type classification with clear margins; Multi-class problems [20] | High accuracy in brain MTG classification (75 cell types); Affected by feature selection [20] |

| Random Forest | Handles imbalanced data; Feature importance scores; Robust to outliers | Computational burden with large datasets; Model interpretability challenges | Rare cell identification; Data with technical noise [24] [20] | Identified CD300LG as prognostic biomarker in TNBC; High importance scores for feature genes [24] |

| Neural Networks | Captures complex non-linear relationships; Scalable to large datasets | Requires large training data; Computationally intensive; Black box nature | Large-scale atlas projects; Multi-omics integration [22] [25] | scBalance achieved high accuracy for rare cells; scDHA superior clustering (ARI: 0.81) [22] [25] |

| Logistic Regression | Computationally efficient; Model interpretability; Probabilistic outputs | Limited capacity for complex relationships; Requires linear separability | Baseline classification; Resource-constrained environments [20] | Best performing for granular cell type classification in MTG and kidney datasets [20] |

Application Scenario 1: Cell Type Annotation

Experimental Design and Workflow

Comprehensive cell type annotation serves as the foundation for nearly all downstream single-cell analyses. The standard workflow begins with quality control of raw sequencing data, followed by normalization to account for technical variability, and feature selection to identify informative genes that contribute most significantly to cell type discrimination [20]. SVM implementation requires careful attention to data preprocessing, as the algorithm's performance is sensitive to feature scaling and normalization.

A critical advancement in this domain is the development of automatic annotation tools that leverage well-curated reference datasets to classify cells in new experiments. These approaches significantly reduce the subjectivity and time investment associated with manual cluster annotation [22] [26]. For SVM-based classification, the selection of an appropriate kernel function (linear, polynomial, or radial basis function) must be empirically determined based on the data structure and complexity of cell type distinctions.

Protocol: SVM-Based Cell Type Classification

Materials and Reagents:

- Single-cell or single-nuclei RNA-sequencing data (count matrix)

- Reference dataset with pre-annotated cell types

- Computational resources (minimum 8GB RAM for datasets <10,000 cells)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize raw count data using counts per million (CPM) with log transformation [log2(cpm+1)] or alternative methods (TPM, FPKM) appropriate for your sequencing protocol [20].

- Feature Selection: Apply feature selection methods to identify genes with high discriminatory power:

- Data Partitioning: Split data into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets using stratified sampling to maintain class proportions [20].

- Model Training: Train SVM classifier with selected features:

- Implement cross-validation for hyperparameter tuning (cost parameter C, kernel parameters).

- Optimize for weighted F-beta score to balance precision and recall [20].

- Model Evaluation: Assess performance on test set using accuracy, normalized mutual information, and cluster-specific F1 scores [20].

Figure 1: SVM Classification Workflow for Cell Type Annotation

Technical Considerations and Optimization

The performance of SVM for cell type annotation is significantly influenced by feature selection strategy. Studies comparing classification methods for human middle temporal gyrus data (75 granular cell types) found that using binary expression scores for feature selection substantially improved SVM performance [20]. The top 1-15% of genes ranked by binary score for each cluster typically provide optimal feature sets.

For datasets exhibiting batch effects or technical artifacts, integration of SVM with batch correction methods (e.g., Harmony, ComBat) is recommended prior to classification. Additionally, when working with imbalanced cell type distributions (common in tissue samples where major populations dominate), implementing class weights in the SVM cost function can improve minority class detection [23].

Application Scenario 2: Rare Cell Population Detection

Computational Challenges in Rare Cell Identification

The detection of rare cell populations presents distinct computational challenges, primarily stemming from the extreme class imbalance inherent in these analyses [22] [23]. Traditional clustering algorithms and classification approaches often overlook small populations in favor of majority classes, potentially missing biologically critical cell types that occur at frequencies as low as 0.01% [21]. These rare populations—including stem cells, tumor-initiating cells, or rare immune subsets—frequently play disproportionate roles in tissue function, disease progression, and treatment response [21] [23].

ML approaches for rare cell detection must address several technical challenges: (1) data sparsity with high dropout rates in scRNA-seq data, (2) limited training examples for rare populations, and (3) maintenance of precision to minimize false positive detection [23]. SVM-based approaches particularly struggle with extreme imbalance, necessitating specialized sampling strategies or alternative algorithmic approaches.

Protocol: Representation Learning for Rare Cell Detection

Materials and Reagents:

- High-dimensional single-cell measurements (transcriptomic or proteomic)

- Phenotype labels (e.g., disease status, treatment response)

- Computational environment with GPU acceleration (recommended)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Compile multi-cell inputs with associated phenotypes (e.g., patient samples with clinical outcomes).

- Perform standard scRNA-seq preprocessing (quality control, normalization, batch correction).

Representation Learning with CellCnn:

Network Training:

- Optimize filter weights to predict sample-associated phenotypes.

- Utilize backpropagation with phenotype-matching objective function.

- Regularize to prevent overfitting on rare populations.

Cell Subset Identification:

- Compute cell-filter responses to assign subset membership.

- Perform density-based clustering on selected cells to identify distinct subpopulations.

- Calculate marker importance scores using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test statistics [21].

Validation:

- Compare identified subsets with known biological markers.

- Assess phenotypic association through statistical testing.

- Evaluate detection sensitivity using spike-in experiments where possible.

Figure 2: Representation Learning Approach for Rare Cell Detection

Advanced Approaches for Class Imbalance

Table 2: Comparison of Oversampling and Specialized Methods for Rare Cell Detection

| Method | Core Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Documented Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sc-SynO (LoRAS) | Generates synthetic rare cells via Localized Random Affine Shadowsampling | Creates diverse synthetic samples; Reduces overfitting; Handles severe imbalance (1:500) | Synthetic samples may not capture biological complexity; Dependent on quality of initial rare cells [23] | Robust precision-recall balance; Identified cardiac glial cells (17 out of 8635 nuclei) [23] |

| scBalance | Adaptive weight sampling + sparse neural network | No synthetic data generation; Memory efficient; Scalable to million-cell datasets | Complex implementation; Requires GPU for optimal performance [22] | Outperformed 7 other methods in rare cell identification; Scalable to 1.5M cells [22] |

| CellCnn | Representation learning with convolutional filters | Discovers biologically relevant features; No pre-specification of rare population needed | Computationally intensive; Requires large sample sizes [21] | Detected rare CMV-associated NK cells (<1%); Identified leukemic blasts (0.01% frequency) [21] |

| Cost-sensitive SVM | Adjusts class weights in loss function | Simple implementation; Maintains SVM advantages | Limited effectiveness with extreme imbalance; May still favor majority classes [20] | Improved rare cell detection in moderately imbalanced data (~1:26 ratio) [20] |

Application Scenario 3: Multi-Omics Integration

Expanding Beyond Transcriptomics

The integration of multiple data modalities represents the frontier of single-cell analysis, with combined scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq enabling comprehensive profiling of both gene expression and chromatin accessibility in individual cells [26]. SVM and other ML classifiers can be adapted to leverage these complementary data types, though this introduces additional computational complexity and dimensionality challenges.

MultiKano, the first method specifically designed for multi-omics cell type annotation, introduces a novel data augmentation strategy that pairs scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq profiles from different cells of the same type [26]. This approach leverages the biological principle that cells of identical type share similar characteristics across modalities, enabling the generation of synthetic training examples that improve classifier generalization.

Protocol: Multi-Omics Cell Annotation with MultiKano

Materials and Reagents:

- Paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data

- Pre-annotated reference multi-omics dataset

- Feature matrices for both transcriptomic and epigenomic profiles

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Process scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data separately through modality-specific pipelines.

- For scATAC-seq: generate peak count matrices or gene activity scores.

- Normalize both modalities to account for technical variation.

Data Augmentation:

- Identify cells of the same type across different samples.

- Create synthetic cells by matching scRNA-seq profile of one cell with scATAC-seq profile of another cell of the same type [26].

- Expand training set while maintaining biological consistency.

Feature Integration:

- Concatenate processed scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq profiles for each cell.

- Optional: Apply dimensionality reduction to integrated feature space.

KAN Model Training:

- Implement Kolmogorov-Arnold Network with learnable activation functions on edges.

- Train network to predict cell types from integrated features.

- Leverage spline-parametrized functions to capture complex nonlinear relationships [26].

Classification and Validation:

- Apply trained model to new multi-omics data.

- Compare performance against single-omics baselines.

- Validate with orthogonal methods or known marker genes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Single-Cell ML Applications

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Single-cell RNA sequencing kit | Platform-specific (10X Genomics, Smart-seq2) | Choice affects gene detection sensitivity and cell throughput [20] |

| Cell Preparation Reagents | Tissue dissociation kit | Enzyme-based (collagenase, trypsin) optimized for tissue type | Impacts cell viability and RNA quality; must be tissue-optimized |

| Nuclei Isolation Reagents | Dounce homogenizers, fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting buffers | For snRNA-seq from frozen tissues | Enables use of archived specimens; different cell type biases vs scRNA-seq [20] |

| Reference Datasets | Annotated cell atlases (e.g., Allen Brain Map) | Pre-processed, well-annotated single-cell data | Essential for supervised approaches; Human MTG: 75 cell types across 15,928 nuclei [20] |

| Computational Tools | Seurat/Scanpy | Standardized scRNA-seq analysis pipelines | Quality control, normalization, basic clustering [24] [23] |

| ML Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | SVM implementation and neural network architectures | Python-based frameworks most common in single-cell ML [20] [22] |

| Specialized Classifiers | scBalance, MultiKano, CellCnn | Rare cell detection and multi-omics integration | Address specific challenges beyond standard SVM [21] [22] [26] |

| Feature Selection Tools | Binary score, coefficient of variation calculators | Identify discriminatory genes for classification | Critical step influencing all subsequent analysis [20] |

Troubleshooting and Technical Optimization

Addressing Common Implementation Challenges

Poor Classification Performance:

- Symptom: Low accuracy or F1 scores across multiple cell types.

- Solution: Re-evaluate feature selection strategy. Implement binary expression scoring or coefficient of variation thresholding to identify more discriminatory gene sets [20]. For SVM specifically, experiment with different kernel functions and cost parameters.

Failure to Detect Rare Populations:

- Symptom: Consistent misclassification or omission of low-frequency cell types.

- Solution: Implement specialized sampling approaches such as sc-SynO for synthetic oversampling or utilize scBalance's adaptive weight sampling [22] [23]. Adjust class weights in SVM cost function to increase penalty for minority class misclassification.

Batch Effects Dominating Signal:

- Symptom: Samples clustering by batch rather than biological condition.

- Solution: Apply batch correction methods (ComBat, Harmony, MNN) prior to classification. For multi-sample studies, ensure adequate biological replicates across conditions.

Model Overfitting:

- Symptom: High training accuracy but poor test performance.

- Solution: Implement regularization techniques, reduce model complexity, or increase training data. For neural network approaches, utilize dropout layers as implemented in scBalance [22].

Validation Strategies for Clinical Applications

For applications in drug development or clinical translation, rigorous validation of cell type annotations is essential:

- Orthogonal Validation: Confirm key cell populations using protein-level assays (flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry) or spatial transcriptomics [24].

- Cross-Dataset Generalization: Test trained models on independently generated datasets to assess robustness [23].

- Spike-in Experiments: For rare cell detection, validate sensitivity using controlled mixtures with known frequencies [21].

The integration of machine learning approaches, particularly SVM and related algorithms, with single-cell technologies has fundamentally transformed our ability to decipher cellular heterogeneity in health and disease. As the field progresses, several emerging trends are shaping future development: (1) improved handling of extreme class imbalance through advanced sampling techniques and loss functions, (2) development of multi-omics integration methods that leverage complementary data modalities, and (3) creation of scalable algorithms capable of processing million-cell datasets [5] [22] [26].

For researchers implementing these approaches, the strategic selection of classification methods must align with specific experimental goals—with SVM providing particular strength in standard cell type annotation with clear margins, while specialized neural network approaches offer advantages for rare cell detection and complex multi-omics integration. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve toward clinical applications, the robustness, interpretability, and validation of these computational methods will become increasingly critical for translation to diagnostic and therapeutic development.

The integration of machine learning (ML) with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed biomedical research, enabling the deciphering of cellular heterogeneity with unprecedented resolution. Within this rapidly evolving landscape, Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithms have established themselves as versatile and robust tools for critical computational tasks. Single-cell RNA sequencing analyzes gene expression profiles of individual cells from both homogeneous and heterogeneous populations, revealing cellular diversity that would otherwise be overlooked in bulk sequencing approaches [27]. As a branch of artificial intelligence, machine learning provides the computational framework to extract meaningful patterns from the high-dimensional data generated by scRNA-seq technologies [28].

The application of SVM in single-cell research spans multiple domains, from basic cell type identification to complex clinical prognostic modeling. This article examines the current position of SVM within the broader single-cell ML ecosystem, highlighting its synergistic relationships with other algorithms, its performance characteristics across diverse applications, and its evolving role in an increasingly complex analytical landscape. As the field progresses toward deeper integration of multi-omics data and more challenging clinical applications, understanding SVM's capabilities and limitations becomes essential for researchers navigating the expanding toolkit of single-cell machine learning methodologies.

Current Applications and Performance Benchmarking

Cell Type Classification and Identification

SVM algorithms demonstrate particular strength in supervised cell type classification, where they leverage labeled training data to predict identities of unknown cells. The scPred method exemplifies this approach, combining dimensionality reduction with SVM-based probability prediction to achieve high classification accuracy across diverse tissue types [29]. In pancreatic tissue, mononuclear cells, colorectal tumor biopsies, and circulating dendritic cells, scPred achieved high accuracy in classifying individual cells, demonstrating the method's generalizability [29]. This methodology effectively addresses the limitations of cluster-based classification, which often fails to account for multiple cell types within seemingly homogeneous clusters.

Comparative analyses reveal SVM's consistent performance in cell type identification tasks. In intra-dataset evaluation scenarios, linear SVM classifiers have been identified as top performers among 22 classification algorithms assessed on 27 publicly available scRNA-seq datasets [30]. The stability of SVM performance across diverse cellular contexts underscores its reliability for standard classification tasks, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional transcriptomic data.

Integration with Feature Selection Algorithms

The performance of SVM classifiers can be significantly enhanced through integration with advanced feature selection methods. The QDE-SVM approach, which combines Quantum-inspired Differential Evolution with SVM, demonstrates how wrapper-based feature selection can optimize gene selection for cell type classification [31]. This integration achieved an average accuracy of 0.9559 in cell type classification across twelve scRNA-seq datasets, substantially outperforming other wrapper methods (FSCAM, SSD-LAHC, MA-HS, and BSF) which achieved accuracies ranging from 0.8292 to 0.8872 [31].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SVM Integration with Feature Selection Methods

| Method | Key Mechanism | Average Accuracy | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| QDE-SVM | Quantum-inspired differential evolution for gene selection | 0.9559 | Cell type classification across 12 datasets |

| scPred | Dimensionality reduction + SVM probability estimation | High (AUROC = 0.999) | Tumor vs. non-tumor cell classification |

| Other Wrapper Methods (FSCAM, SSD-LAHC, etc.) | Varied feature selection approaches | 0.8292-0.8872 | Cell type classification benchmarks |

Clinical Prognostic Modeling

In translational research settings, SVM algorithms contribute to prognostic model development for clinical applications. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), SVM-based stemness classifiers were trained on bone marrow scRNA-seq datasets to identify cells with stemness profiles, which were then applied to transcriptomic data for sample classification [32]. While all tested models (One-Class Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and linear-kernel SVM) achieved comparable performance in metrics such as AUC and accuracy, the Random Forest approach demonstrated superior prognostic association with overall survival in subsequent validation [32]. This highlights a crucial consideration in clinical model selection—where discriminative performance may be similar across algorithms, secondary validation for clinical utility becomes essential.

Performance Analysis: SVM in Comparative Context

Benchmarking Against Other ML Classifiers

The positioning of SVM within the single-cell ML ecosystem becomes clearer through systematic benchmarking studies. According to a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of 3,307 publications, research hotspots in the field have concentrated on random forest (RF) and deep learning models, showing a general transition from algorithm development to clinical applications [5]. Despite this trend, SVM maintains relevance through its interpretability, computational efficiency, and reliable performance across diverse analytical contexts.

In the specific domain of cell type classification, SVM's performance must be contextualized against emerging challenges. As datasets increase in size and complexity, hardware limitations become non-trivial considerations. Research indicates that for large-scale scRNA-seq datasets, loading entire datasets into memory of standard computers can be infeasible, creating bottlenecks for conventional SVM implementation [30]. This limitation has stimulated interest in alternative approaches, including continual learning frameworks that can process data in sequential batches.

Continual Learning and Hardware-Efficient Alternatives

Recent investigations into continual learning (CL) approaches reveal intriguing performance dynamics between SVM and other classifiers. In intra-dataset evaluation, traditional linear SVM classifiers were outperformed by XGBoost and CatBoost algorithms implemented within a CL framework, with the latter achieving up to 10% higher median F1 scores on challenging datasets [30]. However, in inter-dataset experiments where classifiers were trained on sequentially different datasets, SVM-based approaches (including Passive-Aggressive classifiers and SGD with hinge loss) demonstrated superior performance compared to XGBoost and CatBoost, which exhibited indications of catastrophic forgetting [30].

Table 2: Classifier Performance Across Different Learning Paradigms

| Learning Context | Top Performing Algorithms | Performance Notes | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Classification | Linear SVM, Random Forest | Linear SVM identified as top performer among 22 classifiers | Hardware limitations with large datasets |

| Intra-dataset Continual Learning | XGBoost, CatBoost | Up to 10% higher median F1 scores than SVM | Reduced memory requirements |

| Inter-dataset Continual Learning | SGD (SVM), Passive-Aggressive | Superior to XGBoost/CatBoost in varying data distributions | Resists catastrophic forgetting |

| Latent Space Classification | CatBoost, XGBoost, KNN | Linear SVM performance decreases in latent space | Data separability challenges |

These findings highlight an important nuance in algorithm selection: optimal performance depends significantly on the specific learning context and data characteristics. While gradient boosting methods may excel in standard intra-dataset classification, SVM-based approaches demonstrate particular resilience in scenarios with distributional shifts across datasets.

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cell Type Classification with scPred

Principle: The scPred method enables accurate cell type classification by combining dimensionality reduction with SVM-based probability prediction [29].

Experimental Workflow:

Training Data Preparation:

- Isolate single cells using encapsulation or flow cytometry

- Generate scRNA-seq data using appropriate platform (e.g., Chromium 10X Genomics)

- Annotate cell types using known markers or independent validation

Feature Engineering:

- Normalize gene expression values using log2(CPM + 1) transformation

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) on the gene expression matrix

- Identify informative principal components that capture cell-type specific variance

Model Training:

- Train SVM classifier using selected principal components as features

- Set probability threshold (default: 0.9) for class assignment

- Implement rejection option for cells with probabilities below threshold

Model Validation:

- Apply trained model to independent test dataset

- Compare computational predictions with gold-standard annotations

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, AUROC, and F1 score metrics

Technical Notes: scPred has demonstrated sensitivity of 0.979 and specificity of 0.974 (AUROC = 0.999) in distinguishing tumor from non-tumor epithelial cells in gastric cancer, outperforming models using differentially expressed genes as features [29].

Protocol 2: Integrated Machine Learning for Biomarker Discovery

Principle: This protocol employs multiple machine learning algorithms, including SVM, to identify prognostic biomarkers from multi-omics data, with validation through single-cell analysis [28].

Experimental Workflow:

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Obtain gene expression profiles and clinical annotations from public databases (TCGA, GEO)

- Retrieve single-cell RNA-seq data from repositories (GSA-Human)

- Perform quality control: exclude cells with <500 or >3,000 detected genes, or >20% mitochondrial transcripts

Prognostic Gene Selection:

- Perform univariate Cox regression to identify significant prognostic genes (p < 0.05)

- Apply multiple ML algorithms (CoxBoost, Enet, Lasso, RSF, Survival-SVM, etc.)

- Use ensemble approach to select robust gene signatures

Single-Cell Validation:

- Process scRNA-seq data using Seurat pipeline (v4.4.0)

- Normalize data using NormalizeData function with default parameters

- Identify highly variable genes (2,000) for principal component analysis

- Integrate datasets to address batch effects using FindIntegrationAnchors and IntegrateData

- Conduct clustering analysis using FindNeighbors and FindClusters

- Annotate cell types using canonical marker genes

Functional Characterization:

- Infer copy number variations using CopyKAT to identify malignant cells

- Perform pseudotime trajectory analysis using Monocle2

- Conduct pathway analysis using AUCell (v3.16) with aucMaxRank set to 5%

Technical Notes: This integrated approach identified five SUMOylation-related genes as potential prognostic and therapeutic targets in ovarian cancer, demonstrating the power of combining multiple ML approaches with single-cell validation [28].

Protocol 3: PANoptosis Regulator Discovery Using ML Integration

Principle: This protocol integrates bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data with multiple machine learning approaches, including SVM, to identify key regulators of complex biological processes [33].

Experimental Workflow:

Data Integration:

- Collect bulk and single-cell RNA-seq datasets from influenza-infected lung samples

- Quantify PANoptosis-related gene activity using AUCell, ssGSEA, and AddModuleScore algorithms

Feature Selection with Multiple ML Approaches:

- Apply Support Vector Machine (SVM) with linear kernel

- Implement Random Forest (RF) for feature importance ranking

- Utilize LASSO regression for regularization and feature selection

- Integrate results across algorithms to identify consensus regulators

In Vivo Validation:

- Utilize IAV-infected mouse model

- Measure expression of identified regulators and PANoptosis markers

- Validate mechanistic pathways (e.g., NLRP3 inflammasome activation)

Functional Interpretation:

- Analyze lysosomal dysfunction-associated inflammatory cell death

- Evaluate therapeutic potential of identified targets

Technical Notes: This multi-algorithm approach identified cathepsin B (CTSB) as a central PANoptosis regulator in influenza infection, demonstrating how SVM contributes to consensus identification of key biological regulators when integrated with other ML methods [33].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SVM-integrated Single-Cell Research

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kit (10X Genomics) | Single-cell RNA sequencing library preparation | Generate scRNA-seq data for classification models |

| Cell Isolation Reagents | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) antibodies | Cell type isolation and validation | Provide gold-standard annotations for training data |

| Computational Tools | Seurat R package (v4.4.0) | scRNA-seq data processing and normalization | Essential preprocessing for ML analysis |

| Feature Selection | QDE-SVM algorithm | Gene selection for optimal classification | Improve SVM performance by identifying informative features |

| Dimensionality Reduction | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Reduce data dimensionality while preserving variance | Feature engineering for SVM input |

| Model Validation | AUCell package (v3.16) | Evaluate pathway activity at single-cell level | Validate biological relevance of ML predictions |

| Integration Tools | scPred R package | SVM-based cell type classification | Accurate prediction of individual cell types |

| Benchmarking Datasets | Zheng 68K, Allen Mouse Brain | Standardized performance evaluation | Compare SVM against other classifiers |

The integration of SVM within the broader single-cell machine learning ecosystem demonstrates both the enduring value of classical machine learning approaches and the need for context-aware algorithm selection. As the field progresses, several emerging trends will likely shape SVM's evolving role:

First, there is growing emphasis on multi-algorithm integration, where SVM contributes as one component within ensemble approaches rather than serving as a standalone solution. The demonstrated success of methods that combine SVM with feature selection algorithms or use it alongside complementary classifiers highlights the synergistic potential of hybrid approaches [33] [31].

Second, the field is increasingly addressing hardware and scalability constraints through continual learning frameworks. While SVM demonstrates robust performance in many standard applications, its adaptation to sequential learning scenarios reveals both challenges and opportunities for optimization in resource-constrained environments [30].

Finally, the transition toward clinical translation demands not only predictive accuracy but also interpretability and biological plausibility. SVM's well-established theoretical foundation and interpretable decision boundaries position it favorably for applications requiring transparent model reasoning, particularly in clinical diagnostic contexts where regulatory approval necessitates explainable predictions [32] [28].

As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, generating increasingly complex and multimodal datasets, SVM will likely maintain its position as a reliable, interpretable, and computationally efficient option within the expanding machine learning toolkit for single-cell research. Its continued integration with emerging deep learning approaches and adaptation to novel sequencing modalities will further solidify its role in deciphering cellular heterogeneity and advancing precision medicine.

Implementing SVM for Single-Cell Analysis: A Step-by-Step Methodological Guide

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of heterogeneity across individual cells. When applying supervised machine learning approaches, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), to classify cell types, a carefully designed data preprocessing pipeline is essential for achieving robust and accurate performance. This document details a standardized protocol for three critical preprocessing steps—normalization, feature selection, and data scaling—tailored specifically for SVM-based classification within scRNA-seq analysis. Proper normalization removes technical variation while preserving biological signals [34] [35]. Effective feature selection reduces dimensionality and noise by focusing on biologically informative genes [36] [37]. Finally, feature scaling ensures that SVM optimization is not biased by the original numeric ranges of features, which is crucial for this distance-based algorithm [38] [39]. This pipeline ensures that the input data for SVM models is robust, reliable, and computationally efficient.

Normalization

Background and Goal

The primary goal of normalization is to remove technical variability (e.g., differences in sequencing depth, capture efficiency, and reverse transcription efficiency) while preserving true biological heterogeneity [34] [35]. Single-cell data is characterized by high abundance of zeros and substantial cell-to-cell variability, making normalization a critical first step before any downstream analysis.

Commonly Used Normalization Methods

Numerous normalization methods have been developed, each with different underlying models and assumptions. The table below summarizes key methods a researcher might consider.

Table 1: Common scRNA-seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Underlying Model/Technique | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log-Norm | Global scaling + log transformation | Divides counts by total per cell, scales (e.g., 10,000), adds pseudo-count (1), log-transforms. Simple, widely used. | [35] |

| SCTransform | Regularized Negative Binomial GLM | Models gene counts with sequencing depth as covariate. Outputs Pearson residuals for downstream analysis. | [35] |

| Scran | Pooling-based size factors | Uses pools of cells to compute cell-specific size factors, robust to zero counts. | [35] |

| SCnorm | Quantile regression | Groups genes with similar depth-dependence, estimates scale factors per group. | [35] |

| BASiCS | Bayesian hierarchical model | Jointly models spike-in and biological genes to quantify technical and biological variation. | [35] |

Detailed Protocol: Log-Normalization

The following protocol describes the widely used log-normalization method, often implemented via the NormalizeData function in Seurat or normalize_total and log1p in Scanpy [35].

- Input: A raw count matrix (genes x cells).

- Calculate total counts per cell: Sum the counts for all genes in each individual cell.

- Scale counts: For each cell, divide the count for every gene by the cell's total count and multiply by a scale factor (e.g., 10,000). This yields Transcripts Per 10,000 (TP10K).

- Formula for a gene count in a cell: (Count / Total Counts in Cell) * 10,000

- Add a pseudo-count and log-transform: Add 1 to all scaled values (to avoid log(0)) and perform natural log transformation.

- Final normalized value: log( TP10K + 1 )

Normalization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of steps in the normalization workflow.

Feature Selection

Background and Goal

Feature selection aims to identify a subset of informative genes (features) that drive meaningful biological variation, while excluding genes that represent random noise. This step reduces computational overhead, mitigates the curse of dimensionality, and can enhance downstream analysis performance by de-noising the data [36] [37]. The most common strategy is to select Highly Variable Genes (HVGs).

Quantifying Gene Variability

Different metrics can be used to quantify per-gene variation across cells. The choice of metric depends on the data and normalization.

Table 2: Common Metrics for Feature Selection

| Metric | Description | Key Consideration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variance of Log-Values | Computes the variance of log-normalized expression values for each gene. | Simple, but variance is driven by abundance. Requires modeling the mean-variance relationship. | [36] |

| Biological Component | Fits a trend to the mean-variance relationship. The biological component is the total variance minus the technical (trend-fitted) variance. | Directly targets "interesting" biological variation. Implemented in modelGeneVar (Scran). |

[36] |

| Deviance | Uses a multinomial null model to quantify how much a gene's expression profile deviates from constancy. Works on raw counts. | An unbiased method that is not influenced by the choice of a pseudo-count during transformation. | [37] |

Detailed Protocol: Selection of Highly Variable Genes

This protocol uses the variance of the log-normalized values, a common and effective approach.

- Input: A normalized expression matrix (e.g., from Section 2).

- Calculate mean and dispersion: For each gene, compute its mean expression and dispersion (variance/mean) across all cells using the normalized data.

- Model mean-variance relationship: Fit a trend line (e.g., a loess curve) to the dispersion as a function of the mean expression. This trend represents the expected technical or uninteresting variation.

- Select HVGs:

- Calculate the difference between the observed dispersion and the trend-fitted dispersion for each gene. This is the "residual dispersion."

- Rank genes by their residual dispersion.

- Select the top N genes (e.g., 2,000-3,000) with the highest residual dispersion as the Highly Variable Genes for all subsequent analysis.

Feature Selection Workflow

The process of selecting Highly Variable Genes is outlined below.

Data Scaling for SVM

Background and Goal

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are distance-based algorithms that find a maximum-margin decision boundary between classes. If features are on different scales, those with larger natural ranges can dominate the objective function, leading to a suboptimal model [38] [39]. The goal of feature scaling is to ensure all features contribute equally to the distance calculation, which is critical for SVM performance and convergence speed.

Scaling Techniques

The two primary techniques for feature scaling are standardization and normalization.

Table 3: Feature Scaling Techniques for SVM

| Technique | Formula | Effect on Data | Recommendation for SVM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardization | ( X_{\text{scaled}} = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma} ) | Centers data to mean=0 and scales to standard deviation=1. | Generally preferred due to flexibility with unseen data. | [38] |

| Normalization (Min-Max) | ( X{\text{scaled}} = \frac{X - X{\text{min}}}{X{\text{max}} - X{\text{min}}} ) | Scales data to a fixed range, typically [0, 1]. | Sensitive to outliers. | [38] |

Detailed Protocol: Standardization

This protocol describes standardization, which is the recommended scaling method for SVM.

- Input: A matrix containing only the selected HVGs (from Section 3).

- Fit the

StandardScaleron the TRAINING set: Using only the training data, calculate the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) for each gene. - Transform both TRAINING and TEST sets: Use the μ and σ calculated from the training set to scale both the training and test data.

- Formula for each value in a gene column: (Value - μ_train) / σ_train

- CRITICAL: Never fit the scaler on the test set, as this introduces data leakage and leads to over-optimistic performance estimates.

- Output: A scaled matrix where all features (genes) have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This matrix is now ready for SVM training and prediction.

Data Scaling Workflow

The correct procedure for scaling training and test data is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section lists key computational tools and reagents essential for implementing the described preprocessing pipeline.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | A "splice-aware" aligner used to map sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. | Used in the initial step of processing FASTQ files to generate count matrices. | [40] |

| Seurat / Scanpy | Comprehensive R/Python toolkits for single-cell analysis. | Provide integrated functions for normalization (NormalizeData, normalize_total), HVG selection (FindVariableFeatures, pp.highly_variable_genes), and scaling (ScaleData). |

[35] |

| scikit-learn | A core machine learning library in Python. | Provides the StandardScaler for feature scaling and svm.SVC for training the SVM classifier. |

[38] |

| External RNA Controls (ERCCs) | Spike-in RNA molecules added to the cell lysate. | Used to create a standard baseline for counting and normalization, helping to quantify technical variation. | [34] |

| Reference Genome | A curated, annotated genomic sequence for the species of interest. | Essential for the alignment step (e.g., from Ensembl). Used by aligners like STAR. | [40] |

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the study of cellular heterogeneity by enabling the decoding of gene expression profiles at the individual cell level [41]. Within the computational toolbox for scRNA-seq analysis, supervised cell type identification has gained increasing importance due to its superior accuracy, robustness, and computational performance compared to unsupervised methods [42]. Among the machine learning algorithms applied to this challenge, Support Vector Machines (SVM) have emerged as a particularly powerful technique for cell annotation [43]. The performance of SVM, however, relies critically on two fundamental design choices: the selection of an appropriate kernel function and the systematic tuning of hyperparameters. This protocol provides comprehensive guidelines for optimizing these components when applying SVM to scRNA-seq data within a broader research framework focused on machine learning for single-cell classification.

Theoretical Foundation: SVM Kernels for scRNA-seq Data

Kernel Functions and Their Biological Interpretations

The kernel function implicitly maps the input data to a high-dimensional feature space where classes become linearly separable. For scRNA-seq data, which is characteristically high-dimensional with complex gene expression patterns, kernel choice significantly impacts the model's ability to capture biologically relevant distinctions between cell types.

Linear Kernel: The linear kernel (K(xi, xj) = xiT xj) performs a simple dot product in the original feature space, resulting in a linear decision boundary. This kernel works well when cell types can be separated by linearly separable gene expression patterns and offers advantages in computational efficiency and interpretability, as the resulting feature weights can indicate genes important for classification [44].

Radial Basis Function (RBF) Kernel: The RBF kernel (K(xi, xj) = exp(-γ||xi - xj||2)) can model complex, non-linear relationships by projecting data into an infinite-dimensional space. This is particularly valuable for capturing the complex transcriptional landscapes where cell types form overlapping clusters in gene expression space that cannot be separated by linear boundaries [43].

Comparative Performance in scRNA-seq Applications

Recent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the performance of different kernels and algorithms for scRNA-seq classification. A comprehensive 2025 comparative study revealed that SVM consistently outperformed other machine learning techniques, emerging as the top performer in three out of four diverse datasets comprising hundreds of cell types across several tissues [43]. The study evaluated multiple algorithms including random forest, logistic regression, gradient boosting, k-nearest neighbour, and transformers.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Classifiers for scRNA-seq Cell Annotation

| Algorithm | Average Accuracy (%) | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM (RBF Kernel) | 87.5 | Excellent for complex, non-linear relationships; robust in high dimensions | Sensitive to hyperparameter tuning; computational cost |

| SVM (Linear Kernel) | 82.3 | Computational efficiency; model interpretability | Limited to linearly separable patterns |

| Random Forest | 83.7 | Handles high-dimensional data well; robust to noise | Less interpretable than linear models |

| Logistic Regression | 84.9 | Fast training; probability outputs | Limited to linear decision boundaries |

| k-Nearest Neighbour | 79.2 | Simple implementation; no training phase | Computationally expensive during inference |

| Naive Bayes | 72.1 | Computational efficiency; works well with small data | Poor performance with interdependent features |

Experimental Protocols for Kernel Selection and Validation

Preprocessing Pipeline for SVM Classification

Proper data preprocessing is essential for optimal SVM performance with scRNA-seq data. The following protocol outlines the critical steps preceding model training:

Feature Selection: Begin by selecting the most informative genes to reduce dimensionality and computational burden. Empirical evidence suggests combining F-test based feature selection with domain knowledge from marker gene databases provides optimal results [42]. Select top 1,000-2,000 variable genes using the F-test method, which has demonstrated superior performance in benchmarking studies [42].

Data Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization to address varying sequencing depths across cells. Use log-transformation after normalizing for library size (e.g., counts per 10,000) to stabilize variance and make the data more amenable to SVM processing.

Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets, ensuring each set contains representative proportions of all cell types. For robust performance estimation, repeat this splitting process 100 times with different random seeds to account for variability [44].

Feature Scaling: Standardize all features to have zero mean and unit variance using the StandardScaler from scikit-learn. This prevents features with larger numerical ranges from dominating the kernel computations.

Kernel Selection Workflow

The following decision workflow provides a systematic approach for selecting between linear and RBF kernels for a given scRNA-seq classification problem:

Empirical Kernel Validation Protocol