Marker Gene Databases for Single-Cell Annotation: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of marker gene databases and their pivotal role in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data annotation.

Marker Gene Databases for Single-Cell Annotation: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of marker gene databases and their pivotal role in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data annotation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational knowledge of curated databases like CellMarker, PanglaoDB, and singleCellBase. The scope extends to practical methodologies for both manual and automated cell type annotation, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and explores the validation of annotation reliability through both traditional metrics and emerging AI-powered tools. By synthesizing current resources and computational advances, this guide serves as an essential resource for navigating the complexities of cell type identification and accelerating discovery in biomedical research.

The Landscape of Marker Gene Databases: Foundational Resources for Single-Cell Biology

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. A critical step in scRNA-seq data analysis is cell type annotation, which relies heavily on prior knowledge of marker genes—genes uniquely or highly expressed in specific cell types. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to cell marker databases, detailing their composition, functionality, and integration into analytical workflows. We explore the challenges in manual and automated cell annotation, benchmark computational methods for marker gene selection, and present experimental protocols for validating cell types. Furthermore, we examine emerging applications in drug discovery and development, where accurate cell type identification enables precise target selection and patient stratification. This resource serves as a comprehensive reference for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals leveraging scRNA-seq technologies.

The Centrality of Marker Genes in scRNA-seq Analysis

Cell marker genes are fundamental to interpreting scRNA-seq data, serving as unique identifiers that allow researchers to assign biological identity to the clusters of cells revealed through computational analysis. The process of cell type annotation bridges the gap between unsupervised computational clustering and biological meaning, enabling researchers to understand which cell types are present in a sample and in what proportions. In clinical and drug development contexts, accurate annotation is particularly crucial as it can reveal disease-specific cell states, tumor microenvironments, and immune cell compositions that inform therapeutic target selection and biomarker discovery [1] [2].

The fundamental challenge in cell type annotation stems from the complex nature of cellular identity and the technical limitations of scRNA-seq technologies. Ideal marker genes exhibit high specificity (expression restricted to a particular cell type) and sensitivity (consistent expression across all cells of that type). However, in practice, many genes display heterogeneous expression patterns across cell types, and their detection can be affected by technical artifacts like dropout events where genes are not detected in some cells despite being expressed [3]. This biological and technical complexity necessitates robust databases and computational methods to ensure accurate cell type identification.

Cell Marker Databases: Curated Knowledge Repositories

Cell marker databases serve as essential resources that compile and organize experimentally validated relationships between genes and cell types. These databases vary in scope, species coverage, and curation methods, but share the common goal of providing structured biological knowledge to support scRNA-seq annotation.

singleCellBase represents a manually curated resource of high-quality cell type and gene marker associations across multiple species. It contains 9,158 entries spanning 1,221 cell types linked with 8,740 genes, covering 464 diseases/statuses and 165 tissue types across 31 species [4]. The database is meticulously compiled from publications available on the 10x Genomics website, with a rigorous curation process involving preliminary abstract screening, full-text review, evidence extraction, and double-checking of all associations. A key feature of singleCellBase is the substantial effort invested in normalizing and unifying nomenclature for cell types, tissues, and diseases to ensure consistency [4] [5].

Table 1: Major Cell Marker Databases and Their Characteristics

| Database Name | Species Coverage | Cell Types | Marker Genes | Key Features | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singleCellBase | 31 species | 1,221 | 8,740 | Manual curation from 10x Genomics publications; Unified nomenclature | Manual cell annotation across multiple species |

| ScType Database | Human, Mouse | Comprehensive tissue coverage | Extensive collection | Includes positive and negative markers; Specificity scoring | Fully-automated annotation with ScType algorithm |

| PanglaoDB | Human, Mouse | Limited primarily to these species | Curated markers | Focus on human and mouse markers | Annotation for common model organisms |

| CellMarker v2.0 | Human, Mouse | Extensive within these species | Comprehensive | Manual literature curation | Human and mouse studies |

The ScType platform incorporates what is described as "the largest database of established cell-specific markers," which includes both positive and negative marker genes to enhance annotation specificity [6]. Negative markers—genes that should not be expressed in a particular cell type—provide critical exclusion criteria that help distinguish between closely related cell populations. This comprehensive marker database enables ScType to automatically distinguish between subtle cell subtypes, such as immature versus plasma B cells based on CD19/CD20 versus CD138 expression patterns [6].

Methodologies for Marker Gene Selection and Cell Annotation

Computational Methods for Marker Gene Selection

The selection of marker genes from scRNA-seq data is a distinct computational task with different requirements than general differential expression analysis. A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated 59 methods for selecting marker genes using 14 real scRNA-seq datasets and over 170 simulated datasets [7]. Methods were compared on their ability to recover simulated and expert-annotated marker genes, predictive performance, computational efficiency, and implementation quality.

The benchmarking revealed that simple methods, particularly the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Student's t-test, and logistic regression, generally show strong performance in marker gene selection [7]. These methods balance accuracy with computational efficiency, making them suitable for large-scale scRNA-seq datasets. The study also highlighted substantial methodological differences between commonly used implementations in popular frameworks like Seurat and Scanpy, which can significantly impact results in certain scenarios.

starTracer represents a novel algorithm designed to address limitations in traditional marker gene identification approaches. Conventional methods like Seurat's "FindAllMarkers" function use a "one-vs-rest" strategy, comparing each cluster to all others combined. This approach can cause a "dilution" issue where high expression in a single cluster is masked when pooled with lower expressions in multiple other clusters [8]. starTracer instead evaluates expression patterns across all clusters simultaneously, resulting in 2-3 orders of magnitude speed improvement while maintaining high specificity [8].

Annotation Methods and Performance Benchmarking

Cell type annotation methods can be broadly categorized into manual, reference-based, and fully automated approaches:

Manual annotation relies on researcher expertise and consultation of marker databases to assign cell types based on cluster-specific gene expression. While considered the gold standard, this approach is time-consuming and requires substantial prior knowledge [4] [5].

Reference-based methods transfer labels from previously annotated reference datasets to new query data using classification algorithms. Commonly used tools include SingleR, Azimuth, scPred, scmap, and RCTD [9].

Fully automated methods like ScType combine comprehensive marker databases with computational algorithms to assign cell types without manual intervention [6].

A benchmarking study of reference-based methods for 10x Xenium spatial transcriptomics data found that SingleR performed best, with results closely matching manual annotation in accuracy while being fast and easy to use [9]. The study also demonstrated a practical workflow for preparing high-quality single-cell RNA references to optimize annotation accuracy.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cell Type Annotation Methods

| Method | Approach | Accuracy | Speed | Ease of Use | Best Use Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Annotation | Expert curation | High (Gold standard) | Slow | Requires expertise | Final validation; Novel cell types |

| SingleR | Reference-based | High | Fast | Easy | General purpose annotation |

| ScType | Automated with markers | High (98.6%) | Very fast | Easy | Large datasets; Standard tissues |

| Azimuth | Reference-based | Moderate-high | Moderate | Moderate | Integration with Seurat workflows |

| scSorter | Automated with markers | High | Slow | Moderate | When high accuracy is prioritized |

Recent advances include the application of Large Language Models (LLMs) for cell type annotation. The AnnDictionary package provides a framework for using various LLMs to annotate cell types based on marker genes from unsupervised clustering [10]. Benchmarking studies found that Claude 3.5 Sonnet showed the highest agreement with manual annotations, achieving 80-90% accuracy for most major cell types [10].

Experimental Protocols for Marker Gene Validation

Standardized Workflow for Cell Type Annotation

A robust protocol for cell type annotation in scRNA-seq data involves multiple steps to ensure accurate and reproducible results:

Quality Control and Preprocessing: Filter cells based on quality metrics (mitochondrial content, number of detected genes, total counts). Remove doublets using tools like scDblFinder [9].

Normalization and Feature Selection: Normalize data using methods like SCTransform (Seurat) or normalizations in Scanpy. Select highly variable genes for downstream analysis [9].

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) followed by graph-based clustering (Leiden or Louvain algorithms). Visualize clusters using UMAP or t-SNE [9].

Differential Expression Testing: Identify marker genes for each cluster using appropriate methods (Wilcoxon test, t-test, etc.). Apply multiple testing correction and set thresholds for log-fold change and expression prevalence [7].

Cell Type Assignment:

- For manual annotation: Consult marker databases (singleCellBase, CellMarker) to identify cell types based on enriched genes in each cluster.

- For automated annotation: Apply tools like ScType or reference-based methods (SingleR, Azimuth).

- For spatial data: Use specialized methods like RCTD that account for spatial context [9].

Validation:

- Verify annotations using independent methods such as RNA in situ hybridization or immunofluorescence.

- For malignant cells, perform copy number variation analysis using inferCNV to distinguish from healthy cells [9].

- Validate rare cell populations using flow cytometry or other orthogonal approaches.

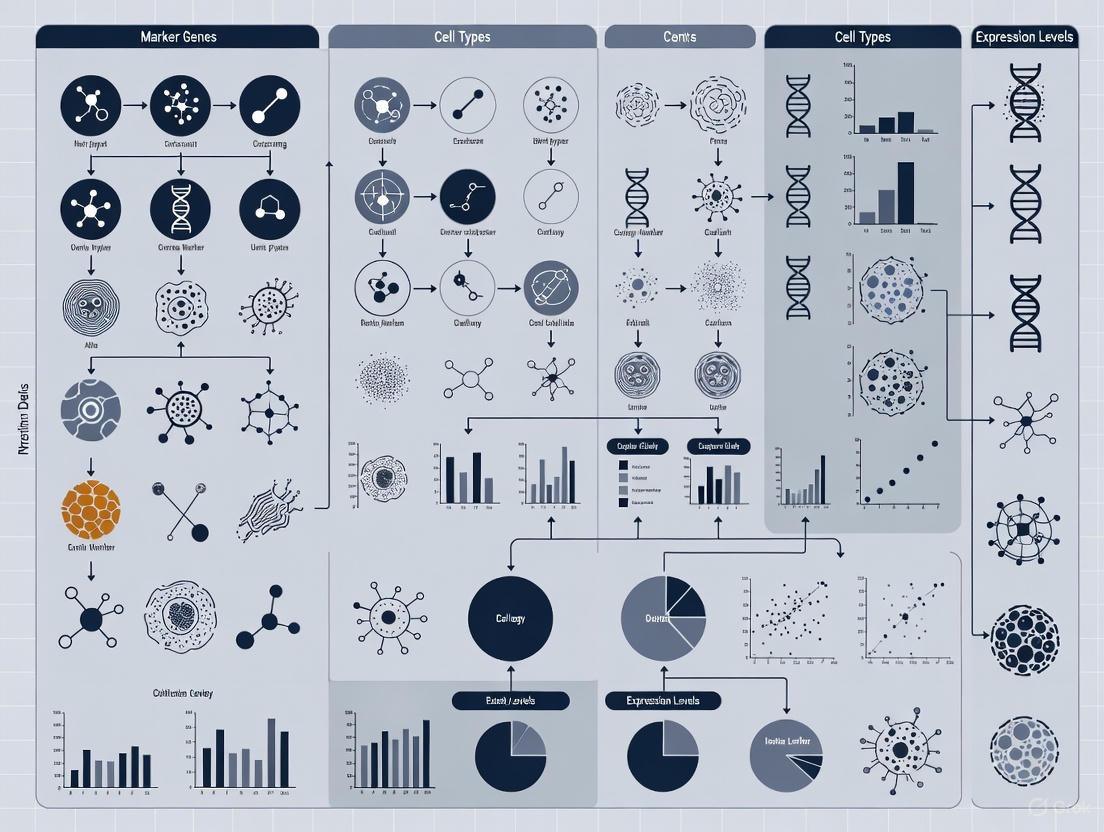

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq Cell Type Annotation Workflow. This workflow outlines the standardized process for annotating cell types in single-cell RNA sequencing data, from quality control to validation.

Experimental Design Considerations

Proper experimental design is crucial for obtaining reliable marker gene information. A systematic evaluation of quantitative precision and accuracy in scRNA-seq data revealed several critical factors:

Cell Numbers: At least 500 cells per cell type per individual are recommended to achieve reliable quantification [3]. Many studies sequence large total cell numbers but have very few cells for specific cell types per sample, compromising accuracy for rare populations.

Technical Variability: Technical replicates should be incorporated to assess precision. Pseudo-bulk approaches (aggregating single-cell expression within samples) can reduce the missing rate from ~90% at single-cell level to ~40% at pseudo-bulk level [3].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio: This metric is key for identifying reproducible differentially expressed genes. The VICE (Variability In single-Cell gene Expressions) tool can evaluate data quality and estimate true positive rates for differential expression based on sample size, noise levels, and effect size [3].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for scRNA-seq Annotation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Platform | Single-cell partitioning & barcoding | High-throughput scRNA-seq library preparation |

| Parse Biosciences Evercode | Reagent | Combinatorial barcoding | Scalable single-cell profiling (up to 10M cells) |

| singleCellBase | Database | Cell type-marker gene associations | Manual cell annotation across multiple species |

| ScType Database | Database | Positive/negative marker genes | Automated cell type identification |

| Seurat | Software | scRNA-seq analysis toolkit | Comprehensive analysis including marker detection |

| Scanpy | Software | scRNA-seq analysis toolkit | Python-based analysis workflow |

| SingleR | Algorithm | Reference-based annotation | Fast cell type labeling using reference data |

| starTracer | Algorithm | Marker gene identification | High-speed, specific marker detection |

| VICE | Tool | Data quality assessment | Evaluating scRNA-seq data quality and DE reliability |

| AnnDictionary | Package | LLM integration for annotation | Automated annotation using large language models |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Cell marker databases and precise cell type annotation play increasingly important roles in pharmaceutical research and development:

Target Identification and Validation: scRNA-seq enables identification of genes linked to specific cell types involved in disease processes. A retrospective analysis of 30 diseases and 13 tissues demonstrated that drug targets with cell type-specific expression in disease-relevant tissues were more likely to progress successfully from Phase I to Phase II clinical trials [2].

Toxicology and Safety Assessment: scRNA-seq can assess responses of various cell populations to potential therapeutics, helping identify cell-type-specific toxicity patterns before clinical trials [1].

Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification: scRNA-seq defines more accurate biomarkers than bulk transcriptomics by capturing cellular heterogeneity. In colorectal cancer, scRNA-seq has led to new classifications with subtypes distinguished by unique signaling pathways, mutation profiles, and transcriptional programs [2].

Mechanism of Action Studies: High-throughput drug screening combined with scRNA-seq provides detailed cell-type-specific gene expression profiles in response to treatment, revealing subtle changes and heterogeneity in drug responses [1] [2].

The integration of perturbation screens with scRNA-seq further enhances drug discovery. One pioneering study measured 90 cytokine perturbations across 18 immune cell types from twelve donors, generating a 10 million cell dataset with 1,092 samples in a single run [2]. This scale enables detection of effects in rare cell populations that would be missed in smaller studies.

Future Directions and Challenges

The field of cell marker databases and scRNA-seq annotation continues to evolve rapidly. Several challenges and emerging solutions deserve attention:

Standardization and Ontologies: Cell type nomenclature remains inconsistent across studies. While databases like singleCellBase attempt to unify terminology, broader adoption of formal cell ontologies is needed [5].

Multi-Species Applications: Most marker databases focus heavily on human and mouse. Resources like singleCellBase that include 31 species represent an important step toward supporting research across model organisms and comparative biology [4].

Integration of Multi-Modal Data: Future databases will need to incorporate protein markers, chromatin accessibility, and spatial information to provide comprehensive cell identity resources.

Dynamic Marker Genes: Cell states are dynamic, yet most current databases treat markers as static. Incorporating temporal and contextual information about marker gene expression will enhance annotation accuracy.

Artificial Intelligence Integration: LLMs and other AI approaches show promise for automating annotation tasks. The AnnDictionary package represents an early example of systematically integrating LLMs into scRNA-seq analysis pipelines [10].

As these developments progress, cell marker databases will continue to evolve from static catalogs to dynamic, intelligent systems that significantly accelerate single-cell research and its applications in understanding biology and developing therapeutics.

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity within tissues and organs. A fundamental step in scRNA-seq data analysis is cell type annotation, the process of assigning identity labels to cell clusters based on their transcriptomic profiles. While supervised and automated methods are emerging, manual annotation—cross-referencing differentially expressed genes with established biological knowledge—remains the gold standard [11] [12]. This process critically depends on access to curated collections of marker genes, which are genes whose expression is characteristic of specific cell types.

The growing volume of scRNA-seq data has spurred the development of numerous public databases to compile and organize this knowledge. Among these, CellMarker, PanglaoDB, and singleCellBase have become widely used resources. Each offers a unique combination of scope, content, and species coverage, making them suited for different research scenarios. This whitepaper provides a technical comparison of these three key databases, detailing their respective capabilities to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate resource for their single-cell annotation projects within the broader context of marker gene database research.

The following table provides a quantitative summary of the core statistics for CellMarker, PanglaoDB, and singleCellBase, highlighting differences in their data volume and species focus.

Table 1: Core Database Statistics and Species Coverage

| Database | Primary Species Focus | Cell Types | Cell Markers | Tissues | Key Quantitative Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellMarker | Human & Mouse | 2,578 | 26,915 | 656 | 83,361 tissue-cell type-marker entries; Includes protein-coding genes, lncRNAs [13] |

| PanglaoDB | Human & Mouse | ~1,023* | Not Specified | 258* | 4.4M+ mouse cells; 1.1M+ human cells; ~10,400 clusters [14] |

| singleCellBase | Multi-Species (31 species) | 1,221 | 8,740 | 165 | 9,158 entries; Covers Animalia, Protista, Plantae kingdoms [11] |

Note: Values for PanglaoDB cell types and tissues are approximated from sample and cluster counts [14].

The data reveals a clear distinction in strategy. CellMarker provides the most extensive collection for human and mouse models, with the highest number of curated tissue-cell type-marker entries [13]. In contrast, singleCellBase sacrifices some volume for breadth of species coverage, encompassing 31 species across multiple biological kingdoms, making it invaluable for studies on non-model organisms [11]. PanglaoDB serves as a central resource not only for its marker compendium but also for its vast repository of raw and processed scRNA-seq data, which includes millions of individual cells [14].

Scope, Content, and Specialized Features

CellMarker 2.0: A Comprehensive Human and Mouse Resource

CellMarker 2.0 is an updated database dedicated to providing a manually curated collection of experimentally supported cell markers in human and mouse tissues. Its scope is deep rather than broad, focusing on the two most common model organisms in biomedical research. A key feature is the inclusion of marker information from 48 sequencing technology sources, including 10X Chromium, Smart-Seq2, and Drop-seq. Furthermore, it has expanded beyond protein-coding genes to include 29 types of cell markers, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and processed pseudogenes [13].

To enhance its utility, CellMarker 2.0 is packaged with six flexible web tools for the analysis and visualization of single-cell sequencing data:

- Cell annotation: For automated cell type identification.

- Cell clustering: To group cells based on transcriptomic profiles.

- Cell malignancy: To assess the malignant state of cells.

- Cell differentiation: To infer cell differentiation trajectories.

- Cell feature: To explore other cellular characteristics.

- Cell communication: To analyze cell-cell interaction networks [13].

PanglaoDB: An Integrated Data and Marker Portal

PanglaoDB serves a dual purpose as both a marker gene database and a search engine for scRNA-seq datasets. It contains a curated list of marker genes, but a significant portion of its content is raw sequencing data, with over 4.4 million mouse cells and 1.1 million human cells from more than 1,300 samples [14]. This integration allows researchers to directly explore the expression of candidate markers across a vast compendium of public data.

The database features a user-friendly interface for browsing and searching its contents. Unique features include a community voting system for markers, where users can upvote or downvote marker-cell type associations, harnessing crowd-sourced knowledge without requiring registration [14]. Additionally, it provides online tools for differential expression analysis directly within the web interface, facilitating rapid validation of marker genes.

singleCellBase: A Multi-Species Annotation Tool

The singleCellBase database was created to address a significant gap in the field: the limited coverage of species beyond humans and mice in existing resources. It is a high-quality, manually curated database of cell markers designed for single-cell annotation across multiple species. Its data is primarily sourced from curated publications on the 10x Genomics website, ensuring a high baseline quality and relevance [11].

A major undertaking in the development of singleCellBase was the manual normalization and unification of cell type, tissue, and disease names. This addresses a common challenge in biology where the same cell type may be referred to by different names across studies. The database also includes a "Visualize" module that allows users to upload their own scRNA-seq data and input a gene of interest to see its expression pattern visualized on UMAP/t-SNE plots, providing direct validation of marker specificity [11].

Experimental and Analytical Methodologies

Manual Curation and Data Collection Workflows

The accuracy of marker databases hinges on their data collection and curation methodologies. Both CellMarker and singleCellBase rely on rigorous manual curation of scientific literature.

singleCellBase Methodology: The curation process involves multiple steps [11]:

- Preliminary Review: Abstracts of literature from the 10x Genomics publications page are screened to remove irrelevant articles.

- Full-Text Survey: Relevant articles and supplementary tables are read in full to extract associations between cell types and gene markers, along with supporting evidence.

- Data Verification: Curated associations are double-checked for accuracy.

- Term Normalization: Significant effort is invested to normalize and unify the names of cell types, tissues, and diseases.

CellMarker Methodology: Similarly, CellMarker is built by manually curating over 100,000 published papers to identify and record cell marker information, tissue type, cell type, and source [13].

Diagram: Simplified Workflow for Manual Curation of singleCellBase

Protocol for Automated Cell Annotation with ScType

Beyond manual lookup, marker databases enable automated cell type identification. The ScType platform provides a robust example of a fully-automated algorithm that leverages a comprehensive marker database (the ScType database) [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Input Data: Provide a single scRNA-seq dataset (post-quality control and normalization).

- Marker Database Loading: Load the ScType database, which contains a comprehensive collection of positive and negative marker genes for various cell types.

- Specificity Scoring: For each cell cluster identified in the data, ScType calculates a cell-type-specificity score. This score ensures that marker genes are not only highly expressed in a cluster but are also specific to a particular cell type when compared to all other clusters and cell types in the sample.

- Cell Type Assignment: The cluster is annotated with the cell type label that achieves the highest aggregate specificity score from its positive markers, while also considering the absence of negative markers.

- Validation: The algorithm includes a single-nucleotide variant (SNV) calling option to help distinguish between healthy and malignant cell populations in cancer applications.

This method has been benchmarked across six scRNA-seq datasets from human and mouse tissues, achieving 98.6% accuracy (72 out of 73 cell types correctly annotated) and outperforming other methods in both speed and accuracy, particularly in identifying closely related cell subtypes [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key resources and tools, derived from the featured databases and methods, that are essential for conducting single-cell annotation research.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Single-Cell Annotation Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Marker Database | Provides pre-compiled, evidence-based gene-cell type associations for manual or automated annotation. | CellMarker, PanglaoDB, singleCellBase [14] [11] [13] |

| Automated Annotation Algorithm | Software for rapidly and systematically assigning cell type labels to scRNA-seq clusters. | ScType [6] |

| Cell Querying Tool | An algorithm that searches large reference databases to find the most similar cells for a query dataset, transferring annotations. | Cell BLAST [15] |

| Integrated Analysis Web Server | Provides a suite of tools for downstream analysis beyond annotation, such as clustering and differentiation analysis. | CellMarker 2.0 Web Tools [13] |

| Visualization Module | Allows for the graphical exploration of gene expression patterns in single-cell data. | singleCellBase "Visualize" Module [11] |

| Reference scRNA-seq Data | Raw or processed single-cell data from public repositories used for validation or as a reference. | PanglaoDB, CZ CELLxGENE, Human Cell Atlas [14] [16] |

CellMarker, PanglaoDB, and singleCellBase are pivotal resources that structure our knowledge of cell identity within the single-cell genomics ecosystem. The choice of database depends heavily on the research question. For deep investigation into human and mouse biology, CellMarker offers the most extensive and tool-rich environment. For researchers who require integrated access to both marker lists and the underlying raw data, PanglaoDB is an ideal starting point. For studies involving non-model organisms or a broad comparative perspective, singleCellBase is the leading resource.

The field continues to evolve with the integration of artificial intelligence. Single-cell foundation models (scFMs), which are large-scale deep learning models pre-trained on vast atlases like those aggregated in these databases, are beginning to transform data interpretation [16]. These models treat cells as "sentences" and genes as "words," learning a fundamental "language" of biology that can be adapted to various downstream tasks, including highly accurate cell type annotation. As these technologies mature, the curated knowledge within CellMarker, PanglaoDB, and singleCellBase will remain the essential bedrock for training, validating, and interpreting these powerful new models.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity, with cell type annotation serving as a critical first step in data analysis. This process has historically relied on marker gene databases derived predominantly from human and mouse studies. This technical guide provides a comparative analysis of the well-established paradigm of human and mouse-focused research against the emerging trend of multi-species database expansion. We examine the methodological frameworks, benchmarking performance, and practical protocols that underpin both approaches, framing the discussion within the broader context of marker gene database development for single-cell annotation research. For researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis highlights the trade-offs between depth in model organisms and breadth across species, offering guidance on selecting appropriate strategies for specific research objectives.

The accurate identification of cell types—cell type annotation—is a prerequisite for deriving meaningful biological conclusions from scRNA-seq data [17]. This process can be performed manually, relying on expert knowledge, or automatically using computational methods that leverage previously characterized marker genes or reference datasets [18]. The emergence of large-scale, curated single-cell "atlas" datasets through initiatives like the Human Cell Atlas (HCA) has further emphasized the need for robust, standardized annotation practices [19].

The development of marker gene databases is thus a foundational activity that supports the entire single-cell research ecosystem. These databases vary significantly in their species coverage, organizational structure, and underlying evidence, creating distinct advantages and limitations for different research contexts. This guide examines the two predominant paradigms in this space.

The Established Paradigm: Human and Mouse Focus

Rationale and Methodological Framework

The concentration on human and mouse models stems from their paramount importance in biomedical research. Mice, in particular, offer a controlled model system for studying human disease mechanisms, developmental biology, and therapeutic interventions. The methodology for building these databases involves extensive manual curation from thousands of publications.

ACT (Annotation of Cell Types) exemplifies this approach, having constructed a hierarchically organized marker map by manually curating over 26,000 cell marker entries from approximately 7,000 publications [18]. This process involves:

- Literature Curation: Searching single-cell articles in PubMed and manually extracting canonical markers and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) used for cell annotation in the original studies.

- Data Standardization: Mapping tissue names to the Uber-anatomy Ontology (Uberon) and cell-type names to the Cell Ontology, correcting nomenclature inconsistencies.

- Integration and Ranking: Employing the Robust Rank Aggregation method to integrate DEG lists from multiple studies for the same cell type, generating a statistically robust, ordered gene list.

Performance and Applications

Methods built upon human/mouse-centric databases have demonstrated strong performance. The WISE (Weighted and Integrated gene Set Enrichment) method used by ACT, which weights markers by their usage frequency across studies, has been reported to outperform other state-of-the-art annotation methods [18]. Furthermore, tools like UNIFAN, which simultaneously clusters and annotates cells using known gene sets, show excellent results on human and mouse data, achieving an Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) of 0.81 and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) of 0.77 on the human PBMC dataset [20].

Table 1: Representative Tools and Databases with a Human/Mouse Focus

| Tool/Database | Core Methodology | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACT [18] | Hierarchical marker map + WISE enrichment | Integrates >26,000 manually curated marker entries; Web server interface | Outperformed state-of-the-art methods in benchmarking |

| Cell Marker Accordion [17] | Consistency-weighted markers from 23 sources | Weights markers by evidence consistency (EC) and specificity (SPs) scores | Improved accuracy vs. ScType, SCINA, et al.; Lower running time |

| UNIFAN [20] | Neural network using gene set activity scores | Simultaneous clustering and annotation; Robust to noise | ARI: 0.81, NMI: 0.77 on human PBMC data |

| ScInfeR [21] | Hybrid (graph-based + reference/markers) | Supports scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, spatial data; Hierarchical subtype ID | Outperformed 10 existing tools in >100 prediction tasks |

Figure 1: Workflow for constructing and applying a human/mouse-focused marker database, from literature curation to automated cell annotation.

The Emerging Frontier: Multi-Species Database Expansion

Drivers and Technical Strategies

While human and mouse research remains central, several forces are driving the expansion into multi-species databases:

- Evolutionary Biology: Understanding the conservation and divergence of cell types across species provides fundamental insights into gene regulatory evolution.

- Agricultural Science: Single-cell atlases for crops like rice (Oryza sativa) can reveal agronomically important cell types and regulatory elements [22].

- Comparative Genomics: Multi-species comparisons help distinguish conserved core biological processes from species-specific adaptations.

The technical approach shifts from literature curation to large-scale, multi-species data generation and computational comparison. A landmark study constructed a single-cell chromatin accessibility atlas for rice from 103,911 nuclei and then comparatively analyzed it with four other grass species (maize, sorghum, proso millet, and browntop millet) comprising 57,552 additional nuclei [22]. This enabled a direct measurement of chromatin accessibility conservation at cell-type resolution.

Key Findings and Implications

Multi-species analyses have revealed that the evolutionary dynamics of regulatory elements are cell-type-dependent. In rice, epidermal accessible chromatin regions (ACRs) in the leaf were found to be less conserved compared to other cell types, indicating accelerated regulatory evolution in the L1-derived epidermal layer [22]. This suggests that certain cell types may be "hotspots" for evolutionary innovation. Furthermore, such atlases allow for the association of ACRs with agronomic quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs), directly linking evolutionary conservation to phenotypic variation [22].

Table 2: Insights from Multi-Species and Cross-Domain Single-Cell Studies

| Study Context | Species Involved | Key Finding | Technical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Evolution [22] | O. sativa, Z. mays, S. bicolor, P. miliaceum, U. fusca | Accelerated regulatory evolution in leaf epidermal cells | scATAC-seq; Cross-species chromatin accessibility comparison |

| Tumor Myeloid Populations [23] | H. sapiens, M. musculus | Identified conserved myeloid populations across individuals and species | scRNA-seq of human and mouse lung cancers |

| Pancreas Cell Atlas [24] | H. sapiens, M. musculus | Detailed transcriptome of 15 pancreatic cell types; Revealed species-specific differences in islet organization | Droplet-based scRNA-seq (inDrop); Comparative analysis |

Comparative Analysis: Strengths, Limitations, and Integration

Performance and Practical Considerations

The choice between a focused or expanded species approach involves trade-offs. Human/mouse-centric tools benefit from a deep, curated knowledge base. For instance, the Cell Marker Accordion directly addresses a major limitation of broad databases: the widespread heterogeneity among annotation sources. By integrating 23 marker databases and weighting markers by their evidence consistency score (ECs), it mitigates the problem of inconsistent markers for the same cell type, which plagues simpler, broader collections [17].

In contrast, multi-species databases are inherently more complex to construct and standardize. However, they enable discoveries that are impossible within a single species, such as identifying conserved ACRs overlapping the repressive histone modification H3K27me3, which were hypothesized to be potential silencer-like cis-regulatory elements [22].

The Integration of Multi-Omics Data

A significant trend that complements species expansion is the integration of multiple data modalities. MultiKano is the first method designed to integrate single-cell transcriptomic (scRNA-seq) and chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq) data for automatic cell type annotation [25]. Its data augmentation strategy creates synthetic cells by matching the scRNA-seq profile of one cell with the scATAC-seq profile of another cell of the same type, improving model generalization. Benchmarking showed it outperformed methods using only scRNA-seq or scATAC-seq profiles [25]. Similarly, ScInfeR is a versatile, hybrid graph-based method that supports annotation across scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, and spatial omics datasets [21].

Figure 2: A decision framework for selecting an appropriate marker database strategy based on research objectives.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Annotation Tools

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Against Protein Expression Ground Truth

Purpose: To validate the accuracy of an automated cell annotation tool using surface protein expression as a high-confidence ground truth, as performed in the validation of the Cell Marker Accordion [17].

- Dataset Selection: Obtain a CITE-seq or AbSeq dataset that simultaneously measures RNA and surface protein abundance in the same cells (e.g., human bone marrow with 25+ antibody tags).

- Ground Truth Definition: Use the surface protein expression levels to manually label each cell with a definitive cell type. This serves as the benchmark.

- Tool Execution: Run the target annotation tool(s) using only the gene expression data from the same dataset.

- Performance Metrics: Calculate accuracy metrics (e.g., accuracy, Cohen's kappa, macro F1-score) by comparing the tool-predicted labels against the protein-derived ground truth labels.

Protocol 2: Cross-Species Chromatin Accessibility Comparison

Purpose: To quantify the conservation and divergence of cis-regulatory elements across species and cell types, following the methodology of the multi-species grass atlas [22].

- Data Generation: Perform scATAC-seq on homologous organs from multiple species (e.g., leaf from rice, maize, sorghum). Strict quality control is essential.

- Cell Type Annotation: Identify cell states in each species using a combination of annotation strategies (e.g., gene activity scores, marker genes, RNA in situ validation).

- Peak Calling and ACR Definition: Call peaks on cell-type-aggregated profiles to define Accessible Chromatin Regions (ACRs) for each cell type in each species.

- Comparative Genomics: Map ACRs from one species to the genomes of others using whole-genome alignment tools. An ACR is considered conserved if it maps to a syntenic, accessible region in the other species.

- Analysis: Calculate the proportion of conserved ACRs per cell type. Identify cell types with significantly high or low conservation rates.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Single-Cell Annotation Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Marker Database | Provides pre-defined gene sets for marker-based annotation; Foundation for many tools. | ACT [18], Cell Marker Accordion DB [17], ScInfeRDB [21] |

| Reference Atlas | A well-annotated scRNA-seq dataset used for reference-based label transfer. | Tabula Sapiens [21], Human Cell Atlas [19] |

| Annotation Algorithm | Software that performs the computational cell type assignment. | ScInfeR [21], SingleR [19], Seurat [21], MultiKano [25] |

| Integration Pipeline | Corrects batch effects and combines multiple datasets for unified analysis. | Scanorama-prior, Cellhint-prior (from scExtract) [19] |

| Multi-Omics Platform | Allows for simultaneous measurement of gene expression and chromatin accessibility in single cells. | Used to generate data for tools like MultiKano [25] |

The field of single-cell annotation is dynamically evolving from a primary reliance on deep, human-and-mouse-centric databases toward a more inclusive paradigm that integrates multi-species and multi-omics data. The human/mouse focus offers unparalleled curation depth and proven performance in biomedical contexts, while multi-species expansion provides the evolutionary context necessary to understand the principles of cellular identity and regulation.

Future progress will depend on overcoming key challenges, including data heterogeneity, insufficient model interpretability, and weak cross-dataset generalization capability [26]. Promising directions include the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) to automate dataset processing and annotation by extracting information directly from research articles [19], and the development of more robust hybrid methods like ScInfeR that combine the strengths of reference-based and marker-based approaches [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic selection of annotation resources—whether focused on model organisms or expanded across species—will continue to be critical for generating accurate, biologically meaningful insights from the vast and growing universe of single-cell data.

In the field of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) research, the accurate annotation of cell types is a fundamental challenge. This process relies heavily on marker genes—specific genes whose expression defines a particular cell type or state. Marker gene databases serve as indispensable repositories of this knowledge, providing the prior information necessary to interpret scRNA-seq data and determine the identity of cell populations within a sample [11]. The utility and reliability of these databases are, however, entirely dependent on the rigor of their curation practices. This whitepaper examines the core components of database curation—manual curation, source literature management, and data quality assurance—framed within the context of building robust, high-quality marker gene databases for single-cell annotation research, an area critical for advancements in biomedicine and drug discovery [27].

The Imperative for Manual Curation

Manual curation is a labor-intensive process conducted by scientific experts who read, interpret, and extract information from the scientific literature. Unlike automated methods like natural language processing (NLP), manual curation ensures a high level of accuracy and contextual understanding, which is paramount for creating reliable knowledge bases [27].

Advantages Over Automated Methods

- Error Detection and Correction: Curators can identify and rectify errors that are invisible to automated algorithms, such as misassigned sample groups or conflicts between a publication and its associated data repository entry [27].

- Contextual Interpretation and Unification: Experts can interpret vague abbreviations, unify disparate naming conventions for cell types and tissues, and apply controlled vocabularies. This transforms heterogeneous data into a consistent, searchable format [11] [27].

- Enhanced Completeness: Manual curation allows for the extraction of rich, contextual metadata, including disease status, experimental evidence, and sequencing technology used, which adds significant value to the core data [11] [28].

Implementation in Marker Gene Databases

Leading marker gene databases are built on a foundation of meticulous manual curation. For example, the singleCellBase database employs a multi-step process where curators manually survey full-text publications and supplementary tables to extract cell type and gene marker associations, which are then double-checked for accuracy [11]. Similarly, CellMarker 2.0 is built by manually reviewing tens of thousands of published papers to collect experimentally supported markers [28]. This human-centric approach is a key differentiator for high-quality resources.

Sourcing and Processing the Scientific Literature

The quality of a database is intrinsically linked to the quality and scope of its source literature. A transparent and systematic approach to literature acquisition is therefore critical.

Source Selection and Screening

Databases employ stringent criteria to identify relevant and high-quality publications. singleCellBase, for instance, uses curated publications from the 10x Genomics website as a primary source to ensure data relevance and quality [11]. CellMarker 2.0 performs large-scale searches in PubMed using specific keywords related to single-cell sequencing and cell marker identification, followed by filtering for journals with high impact factors to prioritize influential studies [28].

The following table summarizes the quantitative outcomes of rigorous literature curation for two major databases:

Table 1: Scale of Manually Curated Data in Marker Gene Databases

| Database | Tissue-Cell Type-Marker Entries | Cell Types | Tissues | Markers (Genes) | Key Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singleCellBase [11] | 9,158 entries | 1,221 types | 165 types | 8,740 genes | 10x Genomics publications |

| CellMarker 2.0 [28] | 83,361 entries (Human & Mouse) | 2,578 types (Human & Mouse) | 656 types (Human & Mouse) | 26,915 genes (Human & Mouse) | 24,591 published papers (2019-2022) |

Data Extraction and Normalization

Once relevant papers are identified, a standardized workflow is used to extract and harmonize the data.

Diagram 1: Workflow for manual literature curation and data processing.

This process involves extracting associations between cell types, marker genes, and tissues [11]. A crucial subsequent step is normalization, where curators map the diverse names used in original studies to standardized terms from established ontologies like Cell Ontology (for cell types) and UBERON (for anatomy) [28]. This unification is vital for enabling cross-study comparisons and accurate data retrieval.

Data Quality Assurance Frameworks

Ensuring data quality is not a single step but a continuous process that must be integrated throughout the data lifecycle. The DAQCORD (Data Acquisition, Quality and Curation for Observational Research Designs) Guidelines provide a comprehensive framework of indicators for this purpose, many of which are generalizable to database curation [29].

DAQCORD Quality Factors

The DAQCORD framework defines five key data quality factors [29]:

- Completeness: The degree to which the expected data has been collected.

- Correctness: The accuracy and unambiguous presentation of data.

- Concordance: The agreement between variables that measure related factors.

- Plausibility: The extent to which data are consistent with general medical and biological knowledge.

- Currency: The timeliness of data collection and its representativeness.

Application to Database Curation

These factors translate directly into curation best practices. For example, a database addresses completeness by striving to cover multiple species and tissue types. Correctness is achieved through the manual double-checking of entries [11]. Plausibility is reinforced by calculating the frequency of cell type-marker associations in the literature and presenting this confidence level to users [11]. The following table outlines key quality challenges and corresponding assurance strategies.

Table 2: Data Quality Assurance Practices in Database Curation

| Quality Challenge | Impact on Data Utility | Quality Assurance practice |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Nomenclature [11] | Prevents data integration and searching. | Manual unification of cell type and tissue names using ontologies. |

| Source Data Errors [27] | Renders data uninterpretable or misleading. | Manual cross-checking between publications and repository submissions. |

| Insufficient Metadata [30] | Limits reproducibility and reuse of data. | Curating rich metadata (sequencing tech, disease state, evidence). |

| Lack of Standardization in Public Repositories [30] | Hinders validation and secondary analysis. | Advocating for and adhering to strict data deposition standards. |

Experimental and Methodological Protocols

The experimental validation of marker genes is a cornerstone of reliable database entries. Furthermore, the computational methods used to analyze single-cell data are evolving rapidly.

Experimental Evidence for Marker Genes

The gold standard for validating a marker gene involves techniques that confirm both gene expression and protein presence at the single-cell level. A cited experimental protocol from a pancreatic cancer study used flow cytometry to sort epithelial cells based on the surface markers CD45 (negative) and EPCAM (positive) [11]. This functional validation confirms the specificity of EPCAM as a marker for epithelial cells. The key research reagents involved in such experiments are listed below.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cell Marker Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Fluorescently Labeled Antibodies (e.g., anti-EPCAM, anti-CD45) | Bind to specific proteins on the cell surface, enabling detection and cell sorting. |

| Flow Cytometer / Cell Sorter | Analyzes and physically separates cells based on fluorescent antibody labeling. |

| scRNA-seq Library Prep Kit (e.g., 10x Chromium) | Prepares genetic material from single cells for sequencing. |

| Validated Cell Lines or Primary Tissues | Provide the biological material containing the cell types of interest. |

Annotation Workflows and Tools

Once data is curated, researchers use it for cell annotation through either manual or automated methods. Manual annotation involves comparing differentially expressed genes from a new dataset against database entries in tools like Loupe Browser [31]. Automated, reference-based annotation uses tools like Azimuth to computationally project new data onto existing, well-annotated reference datasets [31]. The decision logic for choosing an annotation strategy is outlined below.

Diagram 2: A decision workflow for selecting a cell type annotation strategy.

The construction of a marker gene database is a complex endeavor where scientific rigor must be embedded in every stage of curation. As this whitepaper demonstrates, high-quality outcomes are achieved through a commitment to expert manual curation, a systematic and critical approach to source literature, and the implementation of a robust data quality assurance framework based on factors like completeness, correctness, and plausibility. For researchers in single-cell biology and drug development, selecting and utilizing databases that transparently adhere to these stringent practices is critical. Such resources provide a reliable foundation for cell annotation, ensuring that subsequent biological insights and clinical hypotheses are built upon a solid and trustworthy knowledge base. The future of single-cell research will involve ever-larger datasets; upholding these curation standards is not merely best practice but an essential prerequisite for scientific progress and reproducibility.

Within the framework of marker gene databases for single-cell annotation research, accessing data through intuitive web interfaces is a critical facilitator of scientific discovery. The exponential growth of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data has necessitated the development of platforms that allow researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to browse, search, and download crucial cell type and marker gene information without requiring advanced computational skills. These interfaces serve as the essential bridge between complex genomic data and biological interpretation, enabling the translation of raw data into actionable biological insights. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of the data access mechanisms, interface architectures, and practical methodologies that underpin modern single-cell annotation resources, directly supporting the broader thesis that accessible data is foundational to advancing cell annotation research.

Database Architectures and Access Models

Single-cell annotation databases implement varied architectural models to serve diverse research needs, ranging from manually curated collections to reference-based automated annotation systems. Understanding these models is crucial for selecting the appropriate resource for specific research objectives.

Primary Data Access Models

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Single-Cell Annotation Database Access Models

| Database Access Model | Core Functionality | Typical User Interface Components | Data Download Options | Example Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manually Curated Marker Databases | Collection of cell type-specific marker genes from literature | Browsing hierarchies (species/tissue/cell type), keyword search, results filtering | Marker gene lists, cell type associations, full database dumps | CellMarker 2.0, singleCellBase, PanglaoDB |

| Reference-Based Annotation Tools | Automated cell type prediction by comparing query data to reference datasets | File upload portals, parameter configuration panels, interactive visualization | Annotated cell clusters, confidence scores, reference mappings | Azimuth, SingleR, ScType |

| Integrated Analysis Portals | Combined analysis pipeline with embedded annotation capabilities | Workflow managers, integrated visualization tools, code-free analysis environments | Pre-processed data, analysis reports, complete analysis outputs | 10x Genomics Cloud, exvar R package, GPTCelltype |

| Genome Browsers and Archives | Genomic context visualization for marker genes | Genomic coordinate search, track hubs, sequence browsers | Genomic intervals, sequence data, track data | UCSC Genome Browser, GenArk genome archive |

Specialized Query Interfaces

Beyond general browsing, specialized query interfaces enable targeted data extraction. The singleCellBase database exemplifies this approach with three distinct search modalities: (1) Search by Tissue Type allowing hierarchical navigation through biological systems; (2) Search by Cell Type supporting both exact and fuzzy matching of cell type names; and (3) Search by Gene Marker enabling researchers to identify which cell types express specific genes of interest [11]. These interfaces incorporate "fuzzy search" tools that accommodate naming variations and partial matches, significantly enhancing usability when confronting the nomenclature inconsistencies prevalent in single-cell biology [11].

The UCSC Genome Browser implements a powerful Track Search feature that queries track descriptions, group classifications, and track names within selected genome assemblies. This functionality is particularly valuable for situating marker genes within their genomic context, examining regulatory elements, and exploring variation data that may impact gene expression patterns [32].

Quantitative Analysis of Database Contents and Coverage

Understanding the scope and scale of available data is essential for evaluating the comprehensiveness of single-cell annotation resources.

Cross-Species Coverage Metrics

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of singleCellBase Database Coverage

| Metric Category | Specific Measure | Quantitative Value | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Scope | Total entries | 9,158 entries | Comprehensive coverage of cell type-marker associations |

| Cell types covered | 1,221 distinct cell types | Extensive cellular diversity representation | |

| Gene markers documented | 8,740 unique genes | Substantial genomic coverage for annotation | |

| Disease Context | Diseases/statuses covered | 464 conditions | Relevant for disease-specific cell states |

| Tissue Diversity | Tissue types represented | 165 distinct tissues | Broad organ and system representation |

| Species Coverage | Species included | 31 total species | Cross-species comparative analysis capability |

| Taxonomic Range | Kingdoms covered | Animalia, Protista, Plantae | Evolutionary perspective on cell markers |

Source: [11]

The singleCellBase database demonstrates exceptional taxonomic diversity, spanning 31 species across multiple kingdoms, facilitating comparative biology and translational research [11]. This broad coverage is particularly valuable for drug development professionals working with model systems, as it enables mapping of cell types and markers between model organisms and humans.

Experimental Protocols for Database Utilization

Protocol 1: Manual Cell Type Annotation Using Web Interfaces

Objective: To annotate cell clusters from scRNA-seq analysis using manually curated marker gene databases through web interfaces.

Materials:

- List of differentially expressed genes from scRNA-seq clusters

- Computer with internet access

- Web browser (Chrome, Firefox, or Safari recommended)

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Generate a list of top differentially expressed genes for each cell cluster using standard scRNA-seq analysis pipelines (e.g., Seurat, Scanpy). Typically, the top 10 genes per cluster identified by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test provide optimal results [33].

Database Selection: Access a curated marker database such as CellMarker 2.0 or singleCellBase via their web interfaces (https://cellmarker.webapp.com/ or http://cloud.capitalbiotech.com/SingleCellBase/) [31] [11].

Hierarchical Browsing: Navigate the database using the taxonomic hierarchy (Species → Tissue → Cell Type) to identify potential marker genes for cell types relevant to your tissue of interest.

Marker Gene Validation: Cross-reference your differentially expressed genes with database entries, noting both the presence of marker genes and their specificity to particular cell types.

Confidence Assessment: Evaluate the frequency of cell type and gene marker associations in scientific literature as provided by databases like singleCellBase, which graphically presents high-confidence associations [11].

Annotation Assignment: Assign cell type identities to clusters based on the overlap between your differentially expressed genes and established marker genes in the database.

Troubleshooting: If multiple cell types match your gene list, refine using more specific markers or validate through additional database queries. For cell types with conflicting annotations, consult primary literature or use consensus approaches across multiple databases [31].

Protocol 2: Automated Reference-Based Annotation

Objective: To perform automated cell type annotation using reference-based web tools without programming requirements.

Materials:

- Feature-barcode matrix from Cell Ranger or similar preprocessing pipeline

- Internet connection and web browser

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Prepare your feature-barcode matrix (standard output from Cell Ranger) as the input file [31].

Tool Selection: Access a reference-based annotation tool such as Azimuth (https://azimuth.hubmapconsortium.org/) [31].

Project Setup: Create a new project within the web interface and upload your feature-barcode matrix.

Reference Selection: Choose an appropriate reference dataset for your tissue type (e.g., PBMC, motor cortex, kidney).

Analysis Execution: Initiate the automated analysis pipeline, which performs normalization, visualization, cell annotation, and differential expression analysis [31].

Result Interpretation: Review the automatically generated annotations, which typically include both cell type assignments and confidence metrics.

Data Download: Export the results in standard formats for further analysis or publication.

Troubleshooting: If annotation confidence is low, try alternative reference datasets or supplement with manual annotation based on marker genes. The quality of results heavily depends on the similarity between your query data and the reference dataset [31].

Protocol 3: Integrated Analysis and Visualization

Objective: To utilize integrated analysis portals for combined processing and annotation of single-cell data.

Materials:

- Raw or processed single-cell data

- exvar R package or Docker container

Methodology:

- Environment Setup: Install the exvar package using R (

devtools::install_github("omicscodeathon/exvar/Package")) or pull the Docker container (docker pull imraandixon/exvar) [34].

Data Input: Prepare Fastq files or count matrices as input for the analysis.

Pipeline Execution: Utilize exvar functions for integrated analysis:

processfastq()for quality control and alignmentexpression()for differential expression analysiscallsnp(),callindel(), andcallcnv()for genetic variant callingvizexp(),vizsnp(), andvizcnv()for visualization [34]

Interactive Exploration: Use the built-in Shiny applications for interactive data exploration and visualization.

Annotation Integration: Cross-reference results with marker databases through the integrated functionality or manual comparison.

Troubleshooting: For large datasets, ensure sufficient computational resources. Species-specific analyses may require verification of supported organisms in the exvar documentation [34].

Visual Workflow for Data Access and Annotation

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for accessing single-cell annotation data through web interfaces, from initial data submission to final annotation:

Database Access Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive pathway for accessing and utilizing single-cell annotation databases through various web interfaces, from data input to finalized annotations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Single-Cell Annotation

| Tool Category | Specific Resource | Function/Purpose | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated Marker Databases | CellMarker 2.0 | Manually curated resource of cell markers in human/mouse | Web interface: https://cellmarker.webapp.com/ [31] |

| singleCellBase | Multi-species cell marker database with 9,158 entries | Web interface: http://cloud.capitalbiotech.com/SingleCellBase/ [11] | |

| Tabula Muris | Mouse tissue transcriptome data repository | Web interface with gene-specific query [31] | |

| Automated Annotation Tools | Azimuth | Reference-based automated cell annotation using Seurat algorithm | Web application supporting Cell Ranger outputs [31] |

| GPT-4/GPTCelltype | Large language model for cell annotation using marker genes | R package with API access [33] | |

| SingleR | Reference-based annotation with comprehensive tissue coverage | R package with web-accessible references [33] | |

| Integrated Analysis Platforms | exvar | Comprehensive R package for gene expression and variant analysis | R package or Docker container [34] |

| 10x Genomics Cloud | Automated cell annotation integrated with analysis platform | Cloud-based analysis environment [31] | |

| Genomic Context Tools | UCSC Genome Browser | Genomic visualization and context for marker genes | Web interface with custom track upload [32] |

| GenArk | Genome archive with browser capabilities for diverse assemblies | Web interface with IGV outlinks [32] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The landscape of web-accessible single-cell annotation resources is rapidly evolving, with several emerging technologies shaping future capabilities. The integration of large language models like GPT-4 represents a paradigm shift in cell type annotation, demonstrating strong concordance with manual annotations in diverse tissues and cell types [33]. This approach transitions annotation from a manual, expertise-dependent process to a semi- or fully-automated procedure while maintaining accuracy comparable to human experts.

Enhancements in genome browser technologies are improving data accessibility through features like the UCSC Genome Browser's new Item Details popup dialog, which displays track item details without requiring navigation away from the main browser page [32]. Similarly, right-click options for zooming and precise navigation in genePred tracks significantly improve the user experience for exploring the genomic context of marker genes.

The development of containerized applications such as the Dockerized version of the exvar package and the GenomeQC tool ensures reproducibility and accessibility of analysis pipelines [34] [35]. These technologies encapsulate complex computational environments, making sophisticated analyses accessible to researchers without specialized bioinformatics support.

Future developments will likely focus on enhanced integration between annotation databases, analysis platforms, and visualization tools, creating seamless workflows from raw data to biological interpretation. As these technologies mature, they will further democratize single-cell genomics, enabling broader participation in this transformative field by drug development professionals and researchers across the biological sciences.

From Data to Discovery: Methodologies for Applying Marker Genes in Annotation Workflows

Manual cell annotation remains the gold standard in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, providing nuanced understanding of cellular identity that automated methods often struggle to match. This technical guide details a robust, step-by-step protocol for manual annotation that leverages differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and sophisticated marker gene databases. We contextualize this methodology within the broader research landscape of marker gene databases, highlighting how these resources have evolved to address critical challenges in cellular heterogeneity. For researchers and drug development professionals, this guide provides both theoretical framework and practical implementation strategies to enhance annotation accuracy and biological relevance in single-cell studies.

The exponential growth of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to probe cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. Central to interpreting these complex datasets is cell type annotation—the process of assigning biological identities to cell clusters based on their gene expression profiles. Despite the emergence of numerous automated annotation tools, manual annotation persists as the gold standard approach, particularly for novel cell types or states where expert biological knowledge is paramount [33] [18].

The foundation of effective manual annotation lies in the strategic use of marker gene databases, which bridge the gap between computational clustering and biological interpretation. These databases have evolved from simple collections of marker genes to sophisticated, hierarchically organized knowledge systems that capture the complexity of cellular taxonomy across tissues, species, and disease states [36] [18]. The broader thesis of marker gene database research emphasizes that comprehensive, well-curated knowledge bases are not merely convenient references but essential infrastructure for accurate cellular identification.

This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for executing manual cell annotation using database queries and top differentially expressed genes, positioning this methodology within the context of ongoing innovations in marker gene database development that continue to enhance annotation precision and efficiency.

Fundamental Principles of Manual Cell Annotation

Conceptual Foundation

Manual cell annotation operates on the principle that cell types can be identified by their characteristic gene expression signatures. The process typically follows a structured workflow: after computational clustering of cells based on transcriptomic similarity, researchers identify cluster-specific upregulated genes (DEGs) and systematically compare these against known marker genes from curated databases to assign biological identities [18] [37].

The strength of manual annotation lies in its ability to incorporate expert biological knowledge and contextual understanding that automated methods may miss. This approach allows researchers to recognize nuanced expression patterns, identify novel cell populations, and resolve ambiguous cases where expression signatures overlap between related cell types [33]. However, this method requires significant domain expertise and is inherently labor-intensive, particularly for large datasets with numerous clusters [18].

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its advantages, manual annotation faces several challenges that marker gene databases aim to address:

- Subjectivity: Different experts may annotate the same cluster differently based on their training and experience [38]

- Incomplete knowledge: Marker genes for rare, novel, or poorly characterized cell types may be absent from databases [39]

- Dynamic marker expression: Marker genes can vary across tissues, developmental stages, and disease states [39]

- Data quality: Technical noise, batch effects, and low sequencing depth can obscure true biological signals [37]

These challenges highlight the importance of using comprehensive, well-curated databases and following systematic protocols to maximize annotation consistency and accuracy.

The efficacy of manual annotation is directly proportional to the quality and comprehensiveness of the marker gene databases employed. Several curated resources have been developed to support this process, each with distinctive features and coverage.

Table 1: Comprehensive Marker Gene Databases for Manual Cell Annotation

| Database | Species Coverage | Key Features | Cell Types | Tissues | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellSTAR | 18 species | Integrates both reference data & marker genes; 80,000+ marker entries | 889 distinct types | 139 tissues | [36] |

| ACT | Human, mouse | Hierarchical marker map from 7,000 publications; WISE enrichment method | Comprehensive coverage | Pan-tissue and tissue-specific | [18] |

| singleCellBase | 31 species | 9,158 entries across multiple kingdoms; high-quality curated associations | 1,221 cell types | 165 tissue types | [11] |

| CellMarker 2.0 | Human, mouse | Manually curated from 100,000+ publications; multiple marker types | 467 (human), 389 (mouse) | Multiple | [31] |

| PanglaoDB | Human, mouse | Focus on scRNA-seq markers; user-friendly interface | 155 cell types | Multiple | [39] |

These databases vary in their organizational structures, with some employing hierarchical ontologies that reflect biological relationships between cell types. For instance, ACT organizes markers within a sophisticated ontological framework that connects tissues and cell types based on established biological classifications [18]. This hierarchical organization is particularly valuable for annotating at different resolution levels—from broad cellular lineages to specialized subtypes.

Table 2: Specialized Databases for Specific Annotation Contexts

| Database | Primary Focus | Application Context | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azimuth | Reference-based annotation | Web application with Seurat integration | Supports both scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq |

| Tabula Sapiens | Human cell atlas | Multi-organ reference dataset | 28 organs from 24 normal subjects |

| CancerSEA | Cancer functional states | Malignant cell characterization | 14 cancer functional states |

| MSigDB C8/M8 | Human/mouse tissue | Gene set enrichment analysis | Curated cell type signature gene sets |

When selecting databases for annotation projects, researchers should consider species relevance, tissue specificity, evidence quality, and coverage of the cell types expected in their dataset. For comprehensive annotation, consulting multiple databases is often advisable to leverage their complementary strengths and coverage.

Step-by-Step Annotation Protocol

Preprocessing and Differential Expression Analysis

Step 1: Quality Control and Clustering Begin with standard scRNA-seq preprocessing: perform quality control to remove low-quality cells and technical artifacts, then apply unsupervised clustering methods to group transcriptionally similar cells. The resulting clusters represent putative cell populations requiring annotation [37].

Step 2: Identify Cluster-Specific DEGs For each cluster, perform differential expression analysis against all other cells using appropriate statistical tests. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test has demonstrated particular efficacy for this purpose [7] [33]. Select the top DEGs based on both statistical significance (adjusted p-value) and biological effect size (log fold-change). Research suggests using the top 10 DEGs per cluster provides optimal performance for subsequent database queries [33].

Database Query Strategy

Step 3: Systematic Database Interrogation For each cluster, query marker databases using the identified DEGs. The following workflow illustrates this iterative process:

Step 4: Multi-Level Annotation Approach Begin with broad cell class identification (e.g., "immune cells," "epithelial cells"), then progressively refine to specific subtypes (e.g., "CD4+ memory T cells") using increasingly specific marker combinations. This hierarchical approach mirrors the ontological structure of many modern databases [18].

Validation and Confidence Assessment

Step 5: Expression Validation For proposed cell type annotations, verify that canonical markers are expressed in a high percentage of cells within the cluster. A reliable annotation typically exhibits >4 marker genes expressed in ≥80% of cluster cells [38]. Visualize these expression patterns using UMAP/t-SNE plots, violin plots, and dot plots to confirm specificity [37].

Step 6: Handle Ambiguous Cases For clusters with ambiguous or conflicting marker expression:

- Consult additional specialized databases

- Perform literature searches for emerging markers

- Consider the possibility of novel cell states or types

- Utilize computational support tools like ACT's WISE method for additional evidence [18]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Manual Cell Annotation

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker Databases | CellSTAR, ACT, singleCellBase | Provide canonical marker genes for cell types | Consider species, tissue, and evidence quality |

| Reference Atlases | Tabula Sapiens, Tabula Muris, HCA | Offer reference expression patterns | Match tissue and physiological context |

| Analysis Tools | Seurat, Scanpy, Loupe Browser | Enable DEG identification and visualization | Compatibility with data format |

| Visualization Tools | UMAP, t-SNE, dot plots, violin plots | Validate marker expression patterns | Highlight specificity and percentage expression |

| Ontology Resources | Cell Ontology, Uberon | Standardize cell type and tissue nomenclature | Ensure consistent annotation terminology |

Advanced Techniques and Integration with Automated Methods

Hybrid Annotation Approaches

While this guide focuses on manual annotation, researchers increasingly adopt hybrid approaches that leverage both manual and automated methods. For instance, initial automated pre-annotation can be followed by manual refinement using database queries, significantly reducing the annotation burden while maintaining accuracy [33].

Large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have demonstrated remarkable capability in cell type annotation, achieving >75% concordance with manual annotations in most tissues [33]. Tools like LICT (Large Language Model-based Identifier for Cell Types) integrate multiple LLMs to enhance performance, particularly for challenging low-heterogeneity cell populations [38]. These tools can serve as valuable preliminary annotation sources that experts can refine using the manual database query approach outlined in this guide.

Confidence Scoring Systems

Implementing objective credibility evaluation strategies strengthens manual annotation reliability. The LICT tool employs a systematic approach where annotations are deemed reliable if >4 marker genes are expressed in ≥80% of cluster cells [38]. Similar principles can be applied to manual annotation by quantifying the concordance between cluster DEGs and database markers.