Mastering Aseptic Technique: Essential Protocols for Contamination-Free Cell Culture

This article provides a comprehensive guide to aseptic technique for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mastering Aseptic Technique: Essential Protocols for Contamination-Free Cell Culture

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to aseptic technique for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, step-by-step methodological protocols for both 2D and advanced 3D cultures, troubleshooting for common contamination issues, and validation strategies to ensure data integrity and reproducibility. By synthesizing current best practices and novel insights, this resource aims to equip laboratory personnel with the knowledge to maintain sterile work environments, safeguard valuable cell lines, and enhance the reliability of preclinical research and biomanufacturing.

The Principles of Asepsis: Building a Foundation for Sterile Science

In cell culture and bioprocessing, the integrity of research and the safety of therapeutic products are paramount. The critical foundation for ensuring this integrity lies in the rigorous application of contamination control strategies, primarily through aseptic and sterile techniques. While the terms "aseptic" and "sterile" are often used interchangeably in casual conversation, they represent distinct, complementary concepts in the scientific and medical fields. Aseptic technique refers to the set of procedures and practices designed to prevent the introduction of contaminating microorganisms into a sterile environment or culture [1]. In contrast, sterile technique describes a state that is completely free from all living microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and spores [2]. Understanding this distinction is not merely an issue of semantics; it is a fundamental requirement for any researcher, scientist, or drug development professional aiming to produce reliable, reproducible, and uncontaminated results. A single lapse can compromise months of work, invalidate experimental data, or render a cell therapy product unsafe for patient use [2]. This application note delineates the critical differences between these techniques, provides structured protocols for their implementation, and integrates quantitative data on contamination control, all framed within the context of advanced cell culture research.

Defining the Concepts: Aseptic vs. Sterile

The core distinction lies in the objective: sterilization is a state of absolute absence of microorganisms, while asepsis is a dynamic process of protection to maintain that state.

Sterile Technique: Achieving an Absolute State

Sterilization is an absolute state; an item or environment is either sterile or it is not [2]. This state is achieved through processes that destroy or eliminate all forms of microbial life. Common methods include steam sterilization (autoclaving), dry heat, chemical sterilants, and radiation. In a cell culture context, the term "sterile" is most correctly applied to the instruments, environments, and materials that have undergone these processes [1]. For example, an autoclaved set of surgical instruments, a filter-sterilized media solution, or a pre-sterilized disposable pipette are all considered sterile. The efficacy of sterilization is often verified using biological and chemical indicators that confirm the elimination of highly resistant bacterial endospores [3].

Aseptic Technique: Maintaining a Protected State

Aseptic technique, on the other hand, is a collection of procedural practices performed under controlled conditions to prevent contamination from microorganisms [2]. It does not create a sterile state but is used to maintain it. Think of it as a barrier system: the initial environment and tools are rendered sterile, and aseptic technique is the skill set used to handle these components without introducing contaminants from the surrounding air, surfaces, or the operator [4]. This includes actions such as working in a biosafety cabinet, flaming the necks of culture vessels, using sterile pipettes, and wearing appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). The focus is on minimizing the risk of exposure and cross-contamination during experimental procedures [5].

Table 1: Conceptual Comparison of Aseptic and Sterile Techniques

| Feature | Sterile Technique | Aseptic Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | To achieve a state completely free of all living microorganisms [2]. | To prevent the introduction of contaminants into a sterile field or culture [1]. |

| Nature | An absolute, binary state (sterile or not sterile). | A process, a set of practices and procedures. |

| Primary Application | Environments (operating rooms), instruments (scalpels, forceps), and reagents (media, solutions) [3] [1]. | Techniques and procedures (cell culture handling, sample manipulation, surgical procedures) [1] [4]. |

| Common Methods | Autoclaving, dry heat, chemical sterilization, radiation, filtration. | Use of laminar flow hoods, PPE, sterile handling practices, disinfection with 70% ethanol. |

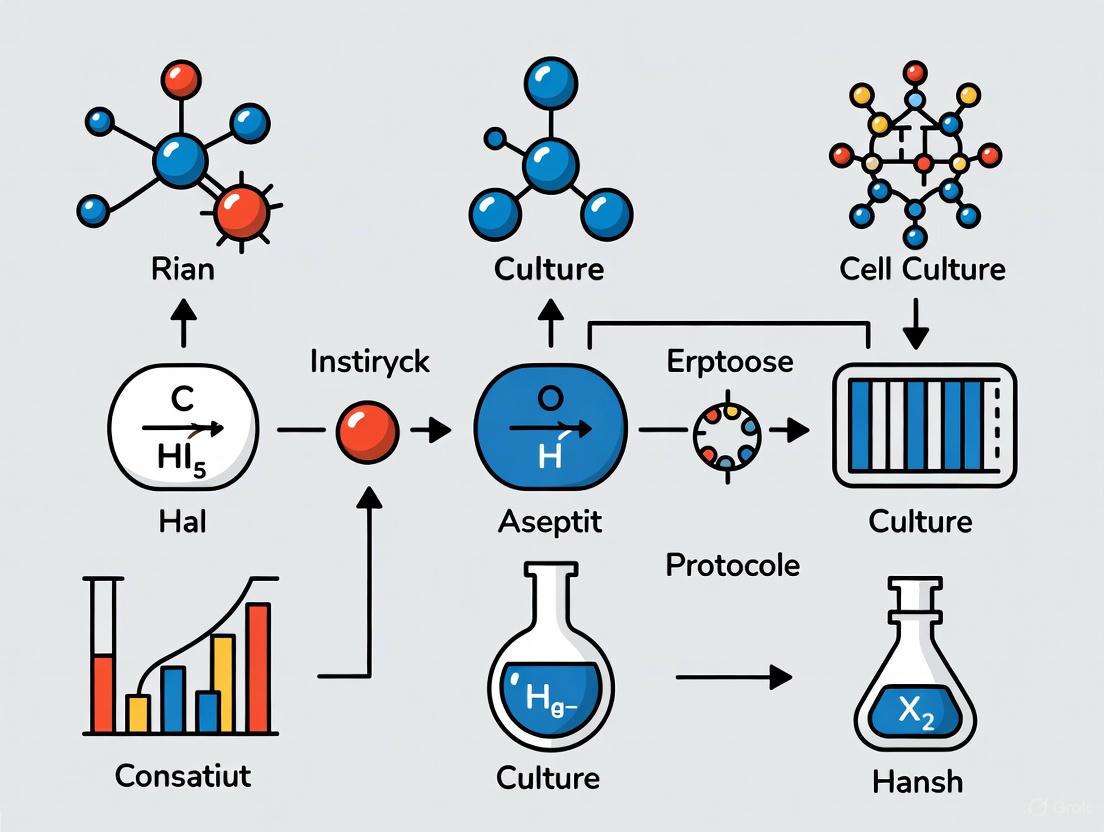

Diagram 1: The sequential relationship between sterile and aseptic techniques in establishing and maintaining a contamination-free workflow.

Quantitative Data and Contamination Analysis

Empirical data underscores the critical importance of precise contamination control. Traditional methods of monitoring microbial load, such as semi-quantitative culture analysis, can be unreliable, leading to undetected contamination that jeopardizes cell cultures and bioprocesses.

A 2021 study compared semi-quantitative culture analysis to the quantitative gold standard (colony-forming units per gram of tissue, CFU/g) using 428 tissue biopsies from 350 chronic wounds. The results, summarized in Table 2, reveal a high degree of variability and overlap in the bacterial loads corresponding to each semi-quantitative category [6]. For instance, "light growth," often considered an insignificant finding, corresponded to a mean bacterial load of 2.5 × 10⁵ CFU/g, a level clinically significant enough to impede wound healing [6]. This imprecision highlights a major vulnerability in relying on such methods for sensitive cell culture work and reinforces the need for impeccable technique to prevent contamination from reaching detectable—and damaging—levels.

Table 2: Correlation Between Semi-Quantitative and Quantitative Culture Results

| Semi-Quantitative Category | Mean Quantitative Value (CFU/g) | Quantitative Range (CFU/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Occasional Growth | 4.9 × 10⁴ | 3.1 × 10² – 7.3 × 10⁶ |

| Light Growth | 2.5 × 10⁵ | 3.0 × 10³ – 1.4 × 10⁷ |

| Moderate Growth | 5.4 × 10⁶ | 1.0 × 10⁴ – 1.0 × 10⁸ |

| Heavy Growth | 1.3 × 10⁸ | 1.0 × 10⁴ – 1.0 × 10¹⁰ |

Data adapted from a comparative study of 428 wound biopsies [6].

Essential Protocols for Aseptic Technique in Cell Culture

The following protocols provide a detailed methodology for establishing and maintaining aseptic conditions during routine cell culture work. Adherence to these steps is critical for preventing the introduction of bacterial, fungal, and mycoplasma contaminants.

Protocol: Standard Aseptic Cell Culture Handling

Objective: To subculture adherent mammalian cells without introducing contamination. Principle: This protocol utilizes a biosafety cabinet (BSC) to create a sterile work area and outlines the steps for sterile handling of cells and reagents to maintain culture purity [2] [4].

Materials & Reagents: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Aseptic Cell Culture

| Reagent/Item | Function | Sterilization Method |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Culture Medium | Provides nutrients for cell growth and proliferation. | Typically filter-sterilized (0.2 µm pore size). |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Used for washing cells to remove residual serum and media without causing osmotic shock. | Autoclaving or filter sterilization. |

| Trypsin-EDTA Detaching Agent | Enzyme solution used to detach adherent cells from the culture vessel surface for subculturing. | Filter sterilization. |

| 70% Ethanol Solution | Broad-spectrum disinfectant used to decontaminate work surfaces, gloves, and reagent exteriors. | Prepared with sterile water. |

| Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) | Cryoprotective agent used for the freezing and long-term storage of cells. | Pre-sterilized or filter sterilized. |

Methodology:

- Preparation: Tie back long hair, remove jewelry, and wash hands thoroughly. Disinfect hands and put on a clean lab coat, safety goggles, and sterile gloves [2] [4].

- Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) Preparation: Turn on the BSC and allow it to run for at least 15 minutes to purge the work surface. Wipe down all interior surfaces (sides, back, and work area) thoroughly with 70% ethanol using a lint-free wipe [2].

- Material Gathering and Organization: Wipe the outside of all media bottles, pipette boxes, and other containers with 70% ethanol before introducing them into the BSC. Arrange materials in a logical, uncluttered manner within the cabinet, ensuring nothing blocks the front or rear grilles to maintain proper laminar airflow [2] [4].

- Cell Handling: a. Washing: Aspirate the old culture medium from the culture vessel. Gently add a sufficient volume of pre-warmed, sterile PBS to the cell monolayer to cover it. Swirl gently and aspirate the PBS to remove any residual serum that would inhibit trypsin. b. Detachment: Add an appropriate volume of pre-warmed trypsin-EDTA to cover the cell layer. Place the vessel in a 37°C incubator for a few minutes until cells detach (verify under a microscope). c. Neutralization: Add a volume of complete medium containing serum (which inhibits trypsin) that is at least double the volume of trypsin used. Pipette the solution gently across the cell layer to disaggregate the cells into a single-cell suspension.

- Subculturing or Analysis: Transfer the cell suspension to a sterile centrifuge tube for centrifugation or directly to new culture vessels containing fresh, pre-warmed medium for subculturing.

- Cleanup: Cap all bottles and vessels immediately. Remove all materials from the BSC and discard waste appropriately. Wipe down the interior surfaces of the BSC again with 70% ethanol [4].

Diagram 2: Aseptic cell culture workflow, detailing the sequential steps from preparation to cleanup.

Advanced Application: Automated Aseptic Sampling in Bioprocessing

Objective: To aseptically extract small-volume samples from microbioreactors for at-line metabolite monitoring without compromising sterility. Principle: Manual sampling is a primary source of contamination and operator variability in bioprocesses, especially in cell therapy manufacturing where small volumes are critical. The Automated Cell Culture Sampling System (Auto-CeSS) was developed to address this challenge [7].

Experimental Protocol Integration (Based on Auto-CeSS):

- System Integration: The Auto-CeSS is aseptically integrated with the bioreactor (e.g., a 2 mL perfusion microbioreactor) using sterile tubing and micro-connectors, establishing multiple aseptic points (APs) in the fluid path [7].

- Sampling Cycle: A microfluidic-peristaltic pump, regulated by pinch valves, accurately draws a predetermined sample volume (as low as 30 µL) from the bioreactor through a sample line.

- Wash and Purge Cycle: To prevent cross-contamination between samples, the system executes a wash cycle using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) from a dedicated wash line, purging the sampling pathway.

- Sample Collection: The extracted sample is directed to a multi-port rotary valve, which diverts it to a designated collection outlet (e.g., a multi-well plate) for subsequent off-line analysis, such as metabolite profiling (glucose, lactate, glutamine) [7].

Key Quantitative Findings: Integration of the Auto-CeSS with a 2 mL microbioreactor for T cell culture demonstrated the system's capability for consistent, periodic sampling (minimum 15-minute interval) of 200 µL supernatant daily. Metabolic profiles (glucose, lactate, glutamine, glutamate) of automatically extracted samples showed insignificant differences compared to manually extracted samples, validating the system's accuracy and its potential to eliminate contamination risks associated with manual handling [7].

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Despite best efforts, contamination occurs. Rapid identification and response are crucial.

Table 4: Common Contamination Sources and Corrective Actions

| Contamination Type | Visual Indicators | Common Sources | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Cloudy, turbid culture medium; sudden pH shift (yellow); fine granules under phase-contrast microscopy [2]. | Non-sterile reagents, contaminated water baths, poor aseptic technique. | Discard culture and affected reagents. Review sterile technique, autoclave water bath reservoirs, use aliquots. |

| Fungal/Yeast | Fungal: floating, fuzzy, filamentous mycelia. Yeast: small, refractile spherical particles in suspension [2]. | Spores in laboratory air, contaminated incubators, operator skin. | Discard culture. Decontaminate incubators and BSC. Enhance environmental controls. |

| Mycoplasma | No visible turbidity; subtle effects on cell growth and morphology; requires specialized detection kits [2]. | Fetal bovine serum, cross-contamination from other cell lines. | Quarantine and discard culture. Test all new cell lines and reagents upon receipt. |

The distinction between aseptic and sterile technique is a cornerstone of robust and reliable scientific practice in cell culture and bioprocessing. Sterile techniques are used to create a germ-free state for instruments, media, and environments, while aseptic techniques are the continuous procedural practices that protect and maintain this sterility. As the field advances towards greater automation, as demonstrated by systems like the Auto-CeSS for small-volume sampling, the fundamental principles of asepsis remain unchanged. Mastering these techniques is non-negotiable; it is the definitive factor that protects invaluable research, ensures the integrity of data, and guarantees the safety and efficacy of cell-based therapies. Diligent application of the protocols and guidelines outlined here provides a solid foundation for a contamination-free laboratory environment.

Aseptic technique is a foundational pillar of successful cell culture, encompassing a set of procedures performed under controlled conditions to prevent contamination by microorganisms [2]. In the high-stakes environments of biomedical research and pharmaceutical development, mastering these techniques is not merely a best practice but a critical necessity. The integrity of experimental data, the conservation of valuable resources, and the very reproducibility of scientific findings depend directly on the consistent application of aseptic principles.

This application note details the profound consequences of technical failures in aseptic technique and provides validated protocols to safeguard cell-based research. We frame this discussion within the context of a broader thesis on cell culture protocols, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on uncontaminated, reproducible biological data for decision-making in both R&D and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) environments.

The High Cost of Contamination

Contamination in cell culture manifests in multiple forms, each with the potential to derail research and development projects. The table below summarizes the primary contamination types, their observable signs, and their direct impacts on research and development.

Table 1: Types of Cell Culture Contamination and Their Impacts

| Contamination Type | Common Signs | Impact on Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Cloudy culture media; rapid pH shift; tiny, shimmering particles under microscopy [8] [2]. | Compromised cell viability; altered metabolism; invalidated experimental endpoints [8]. |

| Fungal/Yeast | Fuzzy, off-white, or black growth (mold); refractile spheres (yeast); turbidity [8] [2]. | Overgrowth of culture; consumption of nutrients; secretion of interfering metabolites [8]. |

| Mycoplasma | No visible turbidity; subtle effects on cell growth, gene expression, and metabolism [8] [9]. | Insidious alteration of cellular function; misleading experimental results; difficult to detect without specialized testing [8] [9]. |

| Viral | Often no immediate visible changes; can alter cellular metabolism [8]. | Safety concerns for derived products; altered cell behavior; difficult to detect and eradicate [8]. |

| Cross-Contamination | Overgrowth by a fast-growing cell line; misidentification [8] [9]. | Invalidated studies due to use of misidentified cell lines; an estimated 30,000 studies have reported research with misidentified cell lines [9]. |

The repercussions of contamination extend far beyond the loss of a single cell culture. In research settings, contamination is a primary contributor to the broader reproducibility crisis in the life sciences. A 2015 analysis reported that over 50% of preclinical research is irreproducible, at an estimated cost of $28 billion annually [9]. Contaminants like mycoplasma can subtly alter gene expression and cellular metabolism, leading to publication of false conclusions and a waste of scientific resources [8] [9].

In GMP manufacturing and drug development, the stakes are even higher. Contamination can lead to the loss of an entire production batch, resulting in massive financial losses, regulatory scrutiny, and serious patient safety risks [8]. The presence of microbial or viral contaminants in a biologics product intended for patient administration represents a critical failure in quality control.

The following diagram illustrates the cascading negative consequences that result from a failure in aseptic technique.

Core Principles and Essential Tools

Aseptic vs. Sterile: A Critical Distinction

A key conceptual foundation is understanding the difference between "sterile" and "aseptic" [2]:

- Sterile describes an absolute state—the complete absence of all living microorganisms. It is achieved through processes like autoclaving, filtration, or chemical treatment. Equipment and reagents are sterilized before use.

- Aseptic Technique is the set of practices used to maintain sterility by preventing contaminants from entering a sterile environment, sample, or culture. It is a continuous process of protection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Aseptic technique relies on both proper practice and the correct materials. The following table details key reagents and equipment essential for maintaining a contamination-free workflow.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Aseptic Cell Culture

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) | Creates a HEPA-filtered, sterile work environment; the primary physical barrier against airborne contaminants [2]. |

| 70% Ethanol | Gold-standard for surface disinfection; disrupts microbial cell membranes through protein denaturation [2] [10]. |

| Sterile, Single-Use Pipettes | Pre-sterilized, disposable pipettes prevent cross-contamination between samples and reagent stocks [8] [2]. |

| Validated Serum & Media | Culture media and supplements from reputable sources that have been tested for sterility and the absence of contaminants like viruses and mycoplasma [8] [9]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Sterile gloves, lab coats, and safety glasses protect the culture from the user and the user from the culture [2] [11]. |

| Mycoplasma Testing Kits | PCR-based or fluorescence-based detection kits are essential for routine screening of this invisible contaminant [8] [9]. |

Validated Protocols for Aseptic Technique

The following step-by-step protocol synthesizes best practices for handling cell cultures under aseptic conditions.

Protocol: Standard Aseptic Cell Culture Handling

Objective: To maintain sterile conditions during routine cell culture passage to prevent microbial contamination and cross-contamination.

Materials:

- Biosafety Cabinet (BSC)

- 70% ethanol in spray bottle and sterile lint-free wipes

- Pre-sterilized pipette tips and culture vessels

- Sterile cell culture media and reagents

- Water bath (for thawing frozen stocks)

- Personal Protective Equipment (sterile gloves, lab coat, safety glasses)

Method:

Preparation:

Biosafety Cabinet Setup:

- Turn on the BSC and allow it to run for at least 15 minutes to purge the work surface with HEPA-filtered air [2].

- Thoroughly disinfect all interior surfaces of the BSC—including the work surface, side walls, and back panel—with 70% ethanol and sterile wipes [2].

- Arrange all materials logically within the cabinet, ensuring no objects block the front or rear grilles to maintain proper laminar airflow [2].

Aseptic Manipulation:

- Work deliberately and minimize rapid movements to avoid disrupting the laminar airflow barrier [2].

- Flame the necks of glass media bottles and flasks using a Bunsen burner or alcohol lamp to create an upward convection current that prevents airborne particles from falling in [2].

- When uncapping vessels, hold caps face-down on the sterile work surface to prevent contamination of the inner surface [2].

- Keep sterile containers open for the minimum time necessary. Do not pass hands or non-sterile objects over the open tops of sterile vessels [2].

- Use sterile pipettes only once. Never use a pipette that has been exposed to the ambient lab environment to handle sterile media or cells [8].

Post-Procedure Cleanup:

- Immediately cap all bottles and flasks.

- Remove all materials from the BSC and dispose of used consumables in appropriate biohazard waste containers.

- Wipe down the entire interior surface of the BSC again with 70% ethanol to ensure it is clean for the next user [2].

The workflow for a typical cell culture experiment, from setup to analysis, is summarized below.

Quality Control and Data Reproducibility

Ensuring Cell Line Authenticity

Aseptic technique also involves protecting the genetic identity of cell lines. Cross-contamination and misidentification are rampant problems, with one study citing over 30,000 publications based on misidentified lines [9]. Quality control is essential:

- Cell Line Authentication: Use Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling for human cell lines to confirm identity against reference databases like Cellosaurus [9].

- Routine Mycoplasma Testing: Implement mandatory, regular screening using PCR, ELISA, or fluorescence-based methods, as mycoplasma contamination affects most cell functions without causing media turbidity [8] [9].

The Role of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Robust reproducibility is achieved through standardization. Developing and adhering to detailed SOPs for all cell culture processes is critical [9]. These SOPs should cover:

- Standardized media formulations and reagent preparation.

- Defined seeding densities and passage protocols.

- Clear documentation and record-keeping for every culture, including passage number and any deviations from the protocol [9].

Aseptic technique is a non-negotiable, foundational discipline in cell culture, serving as the primary defense against the multi-faceted threat of contamination. Its rigorous application is directly linked to the integrity of experimental data, the efficient use of time and financial resources, and the overall reproducibility and credibility of scientific research. By embracing the principles, utilizing the essential tools, and adhering to the validated protocols outlined in this document, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly mitigate risk, enhance the quality of their outputs, and contribute to a more robust and reliable scientific enterprise.

Within the context of cell culture aseptic technique protocols, biological contamination represents a persistent and formidable adversary that can compromise experimental integrity, jeopardize product safety, and invalidate research findings. The nutrient-rich environment optimized for mammalian cell growth simultaneously supports the proliferation of opportunistic biological invaders, including bacteria, fungi, mycoplasma, and viruses. Unlike in vivo systems where immune defenses provide protection, in vitro cultures remain entirely vulnerable to these contaminants, necessitating rigorous defensive strategies [12]. This application note delineates the primary sources and characteristics of common biological contaminants, provides structured protocols for their detection and prevention, and establishes a framework for maintaining contamination-free cell culture systems within research and drug development environments.

Understanding the morphological characteristics, common sources, and visible indicators of each contaminant type forms the foundation of effective contamination control. Different contaminants present unique challenges in detection and eradication, requiring tailored approaches for management.

Table 1: Characteristics and Identification of Common Biological Contaminants

| Contaminant | Common Species/Examples | Primary Sources | Visual/Microscopic Indicators | Culture Medium Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacillus species [12] | Lab personnel, contaminated water baths, non-sterile reagents [12] [13] | Tiny, motile granules between cells; "quicksand" appearance [14] [15] | Rapid turbidity; yellow color shift (acidic pH) [14] [16] |

| Fungi (Yeast) | Candida species [12] | Airborne spores, humidified incubators, cellulose products [17] | Spherical or ovoid particles that reproduce by budding [14] [12] | Turbidity in advanced stages; possible alkaline pH shift [14] [16] |

| Fungi (Mold) | Aspergillus, Penicillium species [12] | Unfiltered air, improper cleaning, contaminated storage areas [17] | Filamentous, thread-like hyphae; fuzzy patches [14] [12] | Floating mycelial clumps; stable pH initially [14] [18] |

| Mycoplasma | M. fermentans, M. orale, M. arginini, M. hyorhinis [12] [19] | Lab personnel (oral cavity), contaminated serum/trypsin, infected cell lines [12] [19] | Not visible by standard microscopy; tiny black dots at high magnification [15] | No turbidity; subtle changes in cell growth/metabolism [18] [19] |

| Viruses | Retroviruses, Herpesviruses, Adenoviruses [12] | Original tissues, serum supplements, cross-contamination [18] [17] | Not visible by light microscopy; may cause cytopathic effects [18] [12] | No consistent change; latent infections common [18] [12] |

Special Considerations for Mycoplasma and Viral Contaminants

Mycoplasma contamination presents unique detection challenges due to its small size (0.15-0.3 µm) and absence of a cell wall, making it resistant to common antibiotics like penicillin and allowing it to pass through standard 0.22µm filters [18] [19]. With an estimated 15-35% of continuous cell lines infected worldwide, mycoplasma can significantly alter cellular metabolism, gene expression, and viability without causing turbidity in the medium [12] [19]. Viral contamination is equally problematic, as these obligate intracellular parasites can establish persistent, silent infections without visible manifestation, potentially compromising both experimental data and laboratory personnel safety, particularly when working with human or primate cells [18] [12].

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Implementing routine, systematic detection protocols is critical for identifying contamination before it spreads through multiple cultures. The following section provides standardized methodologies for detecting various contaminant types.

Routine Microscopic and Visual Analysis

Daily microscopic examination represents the first line of defense against contamination. For bacterial and fungal contaminants, the following protocol should be implemented:

- Daily Observation: Examine cultures under phase-contrast microscopy at 100-400x magnification prior to experimentation or feeding [14] [18].

- pH Monitoring: Document medium color daily using phenol red indicator (yellow = acidic; pink = alkaline; orange = optimal pH ~7.4) [18] [16].

- Turbidity Assessment: Observe medium clarity against a white background; cloudiness suggests microbial proliferation [14] [16].

- Morphological Documentation: Record any changes in cell morphology, adherence, or growth patterns compared to established baselines [14].

Mycoplasma Detection Protocol

Given the prevalence and stealthy nature of mycoplasma, specialized detection methods are required. The DNA fluorescence staining method using Hoechst 33258 provides reliable results:

Sample Preparation:

Staining Procedure:

Analysis and Interpretation:

Table 2: Advanced Detection Methods for Biological Contaminants

| Contaminant | Detection Method | Protocol Summary | Key Reagents/Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria & Fungi | Gram Staining [16] | 1. Heat-fix air-dried smear2. Crystal violet (1 min)3. Iodine mordant (1 min)4. Alcohol decolorization (5-10s)5. Counterstain with safranin (30-60s) | Crystal violet, Gram's iodine, ethanol, safranin, microscope |

| Mycoplasma | PCR Detection [13] [16] | 1. Extract DNA from culture supernatant2. Amplify with mycoplasma-specific primers3. Analyze amplicons by gel electrophoresis | Mycoplasma-specific primers, PCR reagents, thermal cycler, gel electrophoresis system |

| Viruses | PCR/RT-PCR [14] [16] | 1. Extract nucleic acids from cells/supernatant2. Amplify with viral-specific primers3. Detect amplification products in real-time or by gel analysis | Viral-specific primers, PCR reagents, thermal cycler |

| All Microbes | Microbial Culture [16] [17] | 1. Inoculate culture supernatant into nutrient broth/agar2. Incubate at 37°C and 20-25°C3. Monitor turbidity/colony formation for 7-14 days | Soybean-casein digest broth, blood agar, Sabouraud dextrose agar |

Contamination Identification and Response Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Maintaining contamination-free cultures requires access to specific reagents and equipment for prevention, detection, and eradication. The following toolkit represents essential components for an effective contamination control strategy.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Category | Specific Reagents/Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Disinfectants | 70% Ethanol, 10% sodium hypochlorite (bleach), benzalkonium chloride [18] [15] | Surface decontamination of biosafety cabinets, incubators, and work areas |

| Detection Reagents | Hoechst 33258, DAPI, mycoplasma-specific PCR kits, Gram stain kits [18] [16] [15] | Identification and confirmation of contaminating organisms |

| Antimicrobial Agents | Penicillin-Streptomycin solution, Amphotericin B, Tetracycline, Plasmocin [16] [15] | Treatment of contaminated cultures (use as last resort) |

| Sterile Supplies | 0.1µm and 0.22µm filters, sterile pipettes, single-use culture vessels [17] [19] | Maintenance of aseptic environment and sterile reagent preparation |

| Quality Control Tools | Mycoplasma detection kits, endotoxin testing kits, authentication services [14] [15] | Regular screening and validation of cell lines and reagents |

Vigilance against biological contamination requires a multifaceted approach combining rigorous aseptic technique, routine screening protocols, and prompt intervention when contamination is detected. Researchers must recognize that prevention consistently proves more effective than remediation in contamination control. The continuous implementation of these protocols, coupled with systematic documentation and staff training, forms the cornerstone of reliable cell culture practice. By understanding the unique characteristics and sources of common contaminants, research and drug development professionals can implement effective defensive strategies that preserve the integrity of their cell-based systems and ensure the generation of reliable, reproducible scientific data.

Within cell culture aseptic technique protocols, the creation of a reliable barrier between sterile cultures and the non-sterile environment is foundational to research integrity. Successful cell culture is heavily dependent on keeping cells free from contamination by microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses [4]. Nonsterile supplies, media, reagents, and airborne particles are all potential sources of biological contamination that can compromise experimental results, lead to wasted resources, and in a biomanufacturing context, pose patient safety risks [8]. This document delineates the critical roles, selection criteria, and standardized application protocols for three cornerstone components of contamination control: biosafety cabinets, personal protective equipment (PPE), and 70% ethanol. Adherence to these detailed protocols is essential for ensuring the reproducibility and validity of research, particularly in advanced drug development workflows.

Essential Equipment and Reagents

Biosafety Cabinets (BSCs): Primary Engineering Controls

Biosafety Cabinets are primary containment devices that provide a sterile work area through the combined use of laminar airflow and High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters. These filters are capable of trapping particles as small as 0.3 μm with an efficiency of at least 99.97% [20]. Their fundamental purpose is to protect the user and the environment from exposure to biohazards, while most classes (Class II and III) also protect sensitive research materials from external contamination [20].

BSC Classification and Selection

The class of BSC selected must align with the biosafety level of the work and the need for product protection. Table 1 summarizes the principal characteristics of different BSC classes.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Biological Safety Cabinets

| BSC Class/Type | Personnel Protection | Product Protection | Environmental Protection | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Yes | No | Yes | Enclosing equipment (e.g., centrifuges) or procedures that generate aerosols; not for sterile work. |

| Class II (All Types) | Yes | Yes | Yes | The most frequently used cabinets in research and clinical labs for handling low- to moderate-risk agents [20]. |

| Class III | Yes | Yes | Yes | A totally enclosed, gas-tight cabinet for the highest level of protection; used with BSL-3/4 agents. |

Standard Operating Protocol for BSC Use

The following protocol is essential for maintaining the integrity of the cabinet's sterile field.

Prior to Use:

- Preparation: Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water. Put on appropriate PPE (at a minimum, gloves and a buttoned-down lab coat or disposable gown) [20] [4].

- Decontamination: Wipe down all surfaces of the BSC (work surface, side walls, and viewscreen) with 70% ethanol [4].

- Purging: Turn on the blower and let the cabinet purge for at least 10 minutes to establish proper airflow and remove contaminants [20].

- Loading: Load all necessary materials and reagents into the cabinet, ensuring they are wiped with 70% ethanol first. Do not block the front or rear air grills [20] [4].

During Use:

- Minimize Disruption: Avoid rapid movements in and out of the cabinet, as this disrupts the protective airflow barrier [20].

- Work Flow: Always work from a clean to dirty area within the cabinet. Keep all items away from the front grill [20].

- Avoid Contaminants: Never use a Bunsen burner inside a BSC, as heat disrupts airflow and can damage the fragile HEPA filters [20] [4].

After Use:

- Decontaminate and Remove: Decontaminate all materials before removal. Wipe down the interior of the BSC with 70% ethanol [20] [4].

- Purging: Allow the cabinet to run for several minutes to purge any airborne contaminants before turning off the blower and light [20].

- UV Light (if applicable): If equipped, UV lights may be used for additional surface sterilization when the room is unoccupied. Never operate UV light when personnel are present due to risks of skin burns and eye damage [20].

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): A Critical Personnel Barrier

PPE forms an immediate protective barrier between the researcher and the hazardous agent, serving a dual purpose: protecting the user from biological materials and protecting the cell cultures from microorganisms shed by the user (e.g., from skin and clothing) [4].

Key PPE Components and Protocol

- Lab Coat/Gown: A dedicated, clean lab coat or disposable gown must be worn to prevent the introduction of contaminants from personal clothing [4] [21].

- Gloves: Non-sterile or sterile gloves must be worn at all times. Gloved hands should be frequently wiped with 70% ethanol during work. Gloves are single-use and should be disposed of after work or if they become contaminated [4].

- Additional Protection: Safety glasses, masks, and hair coverings are recommended to further minimize contamination risks from the user [22].

70% Ethanol: The Universal Decontaminant

70% ethanol is the disinfectant of choice in cell culture laboratories due to its effectiveness against a broad range of bacteria and fungi, and its rapid evaporation without leaving residues [21]. Its efficacy is concentration-dependent; a 70% solution is more effective than 100% ethanol because the presence of water slows evaporation and allows for sufficient contact time to penetrate microbial cell walls.

Application Protocol

70% ethanol is used to disinfect all surfaces and items that enter the BSC or come into contact with cultures.

- Work Surfaces: Wipe the BSC work surface and other equipment (incubators, microscopes) before and after use, and especially after any spillage [4].

- Reagent Containers: Wipe the outside of all media bottles, flasks, and pipette boxes with 70% ethanol before placing them in the BSC [4].

- Gloved Hands: Routinely wipe gloved hands during procedures to maintain sterility [4].

Integrated Workflow for Aseptic Technique

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and interdependency of the core aseptic technique components to maintain a sterile field.

Experimental Validation and Data

Efficacy of Alcohol Swabbing: A Pilot Study

A 2025 randomized controlled trial investigated the necessity of swabbing single-use injectate vials with 70% isopropyl alcohol, a common aseptic practice. The study hypothesized that this step may not affect the risk of bacterial colonization under clean conditions [23].

Experimental Protocol:

- Design: Double-blind, randomized controlled trial.

- Samples: 40 new single-use vials (20 with aluminum caps, 20 with plastic caps).

- Intervention: Vials were randomly assigned to a "swab" group (firmly swabbed once with 70% isopropyl alcohol and air-dried) or a "no-swab" group.

- Sampling & Culture: A blinded researcher sampled each vial's rubber stopper with a sterile saline-moistened cotton swab. Swabs were plated on blood agar and incubated for 5 days at 35°C in a CO₂ environment. A blinded microbiologist assessed bacterial growth [23].

Results and Analysis:

- Quantitative Data: No bacterial growth was observed in any of the 40 samples after 5 days of incubation. Statistical testing (two-sided Fisher's exact test) confirmed no significant difference between groups (P=1.00) [23].

- Conclusion: The findings suggest that for the specific vial types assessed in a clean clinical environment, routine alcohol swabbing did not provide a measurable sterility benefit. The authors note that further research with larger sample sizes is warranted to confirm these findings [23].

Table 2: Culture Results from Alcohol Swabbing Efficacy Study

| Group | Bacterial Growth (CFU > 0) | No Bacterial Growth (CFU = 0) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swab (70% Alcohol) | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| No-Swab | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| Total | 0 | 40 | 40 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Aseptic Cell Culture

| Item | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol / Isopropanol | Broad-spectrum disinfectant for surfaces, gloves, and equipment. | Effective against bacteria and fungi; fast-evaporating. The preferred concentration for microbial penetration [23] [21]. |

| HEPA Filters | Provides sterile airflow in BSCs and cleanrooms. | Traps 99.97% of particles ≥0.3 μm, including bacteria and spores. Fragile; must be handled with care and certified annually [20]. |

| Sterile Disposable Pipettes | For precise, aseptic transfer of liquid media and reagents. | Single-use to prevent cross-contamination. Used with a pipettor; tips should not touch non-sterile surfaces [4]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Creates a barrier to protect cultures from user and user from hazards. | Includes gloves, lab coats, and safety glasses. Worn to minimize shedding of skin and dirt into cultures [4] [22]. |

| Autoclave | Sterilizes equipment, liquids, and waste using steam and pressure. | Standard cycle: 121°C and 15 psi for 15 minutes. Over-autoclaving can degrade heat-sensitive components [21]. |

The integrated use of biosafety cabinets, appropriate personal protective equipment, and 70% ethanol forms an indispensable defense system against contamination in cell culture. While engineering controls like BSCs establish the primary sterile field, the consistent and correct application of PPE and disinfectants by trained personnel is what makes the technique truly aseptic. The protocols and data presented here provide a foundational framework that can be adapted and scaled, from basic research to current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) environments, ultimately safeguarding both scientific investment and patient safety in drug development.

In the context of cell culture aseptic technique protocols, human-derived contamination represents a critical and persistent risk to research integrity. Personnel are a primary source of biological contaminants, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, which can be introduced through shed skin, hair, respiratory droplets, and improper handling [4] [2]. This application note details evidence-based protocols and methodologies designed to minimize human-derived contamination, thereby safeguarding cell cultures and ensuring the reliability of experimental outcomes in drug development and basic research.

Contamination events carry significant consequences, including invalidated results, wasted resources, and compromised patient safety in translational applications [24]. The following table summarizes common human-derived contaminants and their typical impacts on cell cultures.

Table 1: Common Human-Derived Contaminants and Their Characteristics

| Contaminant Type | Common Sources | Visible Signs in Culture | Impact on Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Skin, breath, improper aseptic technique | Cloudy (turbid) media; possible pH change [2] | Altered cell growth; cytokine release; complete culture loss [4] |

| Fungal/Yeast | Skin, hair, laboratory environment | Fuzzy or powdery colonies (mold); spherical particles (yeast) [2] | Nutrient depletion; culture overgrowth; toxic byproducts [25] |

| Mycoplasma | Oral flora, contaminated reagents | No visible turbidity; subtle morphological changes [2] | Altered metabolism, growth rates, and gene expression [4] |

| Viral | Primary human cell lines, laboratory personnel | Often latent; may require PCR for detection [26] | Changes in cell viability, proliferation, and transcriptome [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Human-Derived Contamination

Protocol 1: Personal Hygiene and Preparation for Laboratory Entry

Principle: To establish a physical and procedural barrier between the researcher and the sterile cell culture environment [2].

Materials:

- Dedicated laboratory shoes or shoe covers [27]

- Clean, non-shedding lab coat (buttoned/zipped) [2]

- Nitrile or latex gloves

- Hair net or bouffant cap

- Safety glasses or face shield

- Hand soap and 70% ethanol for disinfection [4]

Methodology:

- Remove External Clothing Items: Store personal items like jackets, bags, and hats in a designated area outside the cell culture laboratory [4].

- Hand Washing: Thoroughly wash hands and forearms with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, drying with disposable paper towels [4].

- Don Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): In sequence, put on:

- Final Disinfection: Upon entering the culture room or before approaching the biosafety cabinet (BSC), disinfect gloved hands with 70% ethanol [4].

Protocol 2: Aseptic Workflow within a Biosafety Cabinet (BSC)

Principle: To maintain sterility of the work area and prevent contamination during open-container manipulations [2].

Materials:

- Laminar Flow Biosafety Cabinet (BSC)

- 70% ethanol and lint-free wipes

- Pre-sterilized pipettes, tips, and culture vessels

- Bunsen burner or alcohol lamp (if used by the institution) [2]

- Waste container for used tips and disposable items

Methodology:

- BSC Preparation: Turn on the BSC and allow it to run for at least 15 minutes to purge particulate matter from the work surface [2]. Wipe all interior surfaces—including the work area, side walls, and back—with 70% ethanol [4] [2].

- Material Organization: Arrange all necessary sterile reagents, media, and equipment in an uncluttered manner within the cabinet. Ensure items are placed at least six inches from the front grille to maintain laminar airflow [2].

- Aseptic Handling:

- Work deliberately and slowly to minimize turbulence [4].

- Flame the necks of bottles and flasks using a Bunsen burner or alcohol lamp before opening and after closing to create a sterile convection current [2].

- When removing caps, never place the sterile inner surface face-up. Place it face-down on the disinfected work surface [4].

- Avoid speaking, singing, or whistling over open containers to prevent droplet contamination [4].

- Never use a sterile pipette more than once to avoid cross-contamination [4].

- Cleanup: Discard all waste materials. Upon completion of work, wipe down the BSC interior surfaces again with 70% ethanol [2].

Protocol 3: Monitoring and Verification of Contamination

Principle: To routinely screen for overt and covert contaminants to validate the health and sterility of cell cultures [2].

Materials:

- Inverted phase-contrast microscope

- Mycoplasma detection kit (e.g., PCR-based, Hoechst staining)

- Sterile culture media for negative controls

Methodology:

- Daily Visual Inspection: Observe culture media for cloudiness (turbidity) or unusual color changes, which can indicate bacterial growth [2].

- Microscopic Examination: Daily, examine cells under an inverted microscope for signs of contamination. Look for:

- Routine Mycoplasma Testing: Perform mycoplasma testing quarterly or for each new cell line introduced into the laboratory, using a validated method such as PCR [2].

- Control Cultures: Maintain negative control cultures (media only) to monitor the sterility of reagents and the environment.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for personnel entering and working within a cell culture facility, integrating the protocols outlined above.

Personal Hygiene and Aseptic Workflow for Cell Culture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for executing the protocols and maintaining a contamination-free cell culture environment.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Contamination Control

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol | Primary disinfectant for gloves, BSC surfaces, and exterior of reagent bottles [4] [2]. | More effective than higher concentrations due to better penetration [2]. |

| Sterile Disposable Gloves | Creates a barrier between personnel and cultures; prevents transfer of skin flora [4]. | Change frequently, especially after touching non-sterile surfaces [2]. |

| Laminar Flow BSC | Provides a HEPA-filtered, sterile work environment for culture manipulations [27] [2]. | Must be certified annually; run for 15+ min before use to stabilize airflow [2]. |

| HEPA Filter | Traps 99.9% of airborne particulates and microbes, creating the sterile air for the BSC [27]. | Integrity must be regularly tested; lifespan depends on usage [27]. |

| Sterile Pipettes and Tips | For sterile liquid transfer without introducing contaminants [4]. | Use single-use only to prevent cross-contamination between cultures and reagents [4]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | For routine screening of this common, invisible contaminant [2]. | PCR-based methods are highly sensitive and recommended for definitive results [2]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Reduces human error and direct contact with samples, minimizing contamination risk [27]. | Enclosed hood with HEPA filtration provides an additional sterile barrier [27]. |

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Aseptic Protocol for the Lab

Within the framework of aseptic technique protocols for cell culture, the initial setup of the biosafety cabinet (BSC) and sterile field constitutes the most critical step for ensuring research integrity. Successful cell culture depends heavily on keeping cells free from contamination by microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses [4]. Nonsterile supplies, airborne particles, unclean equipment, and dirty work surfaces are all potential sources of biological contamination that can compromise experimental results and lead to costly losses of valuable cell lines and reagents [4]. This protocol outlines detailed methodologies for establishing a proper sterile field and preparing the biosafety cabinet, providing the foundation for all subsequent aseptic procedures in mammalian cell culture.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for proper disinfection and maintenance of the sterile field:

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Sterile Field Preparation

| Reagent | Concentration | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 70% | Surface disinfection; effective against most bacteria and fungi [28] | Primary disinfectant for wiping down BSC surfaces and gloves; allows sufficient contact time for evaporation [4] [2] |

| Sodium Hypochlorite | 1% | Powerful disinfectant for contamination incidents [28] | Used for periodic deep cleaning or after known contamination events [28] |

| Virkon-S | 1% | Broad-spectrum disinfectant for persistent contaminants [28] | Applied in triple-cleaning strategy for stubborn contamination sources [28] |

| Sterile Distilled Water | N/A | Removing disinfectant residues | Used after bleach application to prevent corrosion of stainless steel surfaces [29] |

Methodology

Pre-Preparation Procedures

Proper preparation begins before entering the cell culture laboratory:

- Personal Hygiene: Wash hands thoroughly with germicidal soap before entering the laboratory [29].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Don appropriate PPE including a long-sleeved lab coat, gloves, and safety goggles [4] [2]. Gloves should be changed frequently, especially after touching non-sterile surfaces [2].

- Material Gathering: Collect all necessary materials before beginning work to minimize movement during the procedure. Extra supplies should be placed outside the BSC [29].

Biosafety Cabinet Setup Protocol

The BSC (Class II) is designed to prevent escape of pathogens into the workers' environment and bar contaminants from the research work zone through HEPA-filtered air [29].

Table 2: Sequential BSC Preparation Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Purpose | Timing/Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cabinet Activation | Turn on BSC and allow to run for at least 15 minutes [2] (or 5 minutes [30]) before beginning work. | Allows cabinet airflow to stabilize and purges airborne contamination from work area [29] [2]. | 15-30 minutes pre-work |

| 2. Surface Disinfection | Thoroughly wipe all interior surfaces (work surface, side walls, back panel) with 70% ethanol [4] [2]. | Eliminates microbial contaminants from surfaces; 70% concentration provides optimal bactericidal activity [28]. | Before material placement |

| 3. Material Placement | Arrange all necessary materials strategically within the hood, ensuring workflow from "clean to dirty" [29]. | Organized workflow prevents crossing contaminated items over clean ones [29]. | After surface disinfection |

| 4. Item Disinfection | Wipe outside of all bottles, flasks, and containers with 70% ethanol before introducing to BSC [4]. | Prevents introduction of contaminants from container exteriors. | Before opening containers |

| 5. Pre-Work Purging | Once materials are placed, wait 2-5 minutes before beginning work [29]. | Allows sufficient time for cabinet air flow to purge airborne contaminants introduced during setup [29]. | 2-5 minutes |

Establishing and Maintaining the Sterile Field

The following practices are essential for maintaining sterility during work procedures:

- Spatial Awareness: Keep all equipment and materials at least 4-6 inches inside the cabinet window and away from the front grille [29] [2]. Never block the rear exhaust grill [29].

- Traffic Control: Minimize room activity that can create disruptive air currents [29]. The ideal location for a BSC is at a quiet end of the laboratory, removed from doorways and air conditioning/heating vents [29].

- Movement Minimization: Limit rapid movements of hands and arms into and out of the BSC, as such movement causes turbulent air currents that disrupt the air barrier [29].

- Container Management: When removing caps, place them with the opening facing down on the sterile work surface [4]. Minimize the time that containers remain open [4].

- Flaming Practices: While some protocols recommend flaming bottle necks with a Bunsen burner [2], others explicitly advise against using a Bunsen burner in a BSC as the flame can cause turbulence in the airstream and the heat may damage the HEPA filter [29]. If a procedure requires a flame, use a burner with a pilot light and place it to the rear of the work space [29].

The workflow for the complete pre-work preparation process is systematically outlined in the following diagram:

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

BSC Certification and Maintenance

Regular certification and maintenance of the BSC are imperative for proper function:

- Certification Schedule: BSCs must be tested and certified at the time of installation, after moving, after servicing internal plenums, after replacing filters, and at least annually thereafter [29].

- Filter Monitoring: Many BSCs have gauges to indicate pressure differential across the supply filters. If filters must be replaced, the BSC must be decontaminated first [29].

- Operational Considerations: Unless the BSC is hard-ducted to an outside exhaust system, do not use noxious, toxic, or corrosive chemicals which create a hazardous atmosphere since the BSC recirculates filtered air into the laboratory space but does not remove gas or vapor state contaminants [29].

Contamination Source Identification

When contamination occurs, systematic identification of sources is necessary:

- Incubator Inspection: Incubators are frequently identified as contamination sources, particularly their internal air, shelves, and water trays [28].

- Microscope Examination: Microscope stages and objectives can harbor contaminants and are often overlooked [28].

- Environmental Monitoring: Regular monitoring of laboratory surfaces using sterile swabs and blood agar plates can identify contamination sources before they affect cultures [28].

Ultraviolet Light Considerations

Ultraviolet (UV) lamps are sometimes used in BSCs but require careful consideration:

- Limited Efficacy: UV light is useful for extra precaution in keeping the work area decontaminated between uses but should never be relied on alone to disinfect a contaminated work area [29].

- Safety Hazards: UV lamps must be turned off when the room is occupied to protect occupants' skin and eyes from UV exposure, which can cause burns to the corneas and skin cancer [29].

- Maintenance Requirements: UV lamps must be cleaned weekly with 70% ethanol to maintain effectiveness and tested periodically to ensure sufficient energy output [29].

Proper pre-work preparation of the sterile field and biosafety cabinet establishes the foundational conditions necessary for successful cell culture experimentation. By meticulously following these protocols for BSC setup, material preparation, and sterile field maintenance, researchers can significantly reduce the risk of biological contamination, thereby protecting valuable cell cultures, ensuring experimental reproducibility, and maintaining the integrity of scientific research. Regular quality control measures, including BSC certification and systematic monitoring for contamination sources, provide additional safeguards for maintaining optimal aseptic conditions in the cell culture laboratory.

Aseptic technique is a fundamental set of procedures designed to create a barrier between microorganisms in the environment and the sterile cell culture, thereby reducing the probability of contamination [4]. In the context of routine culture, consistent application of aseptic technique is critical for maintaining cell line integrity, ensuring experimental reproducibility, and protecting valuable laboratory resources. Contamination events can compromise research outcomes, lead to erroneous conclusions, and result in significant time and financial losses [11]. This guide provides a comprehensive, practical checklist and detailed protocols to help researchers establish and maintain impeccable aseptic practices for successful cell culture work.

Fundamental Principles of Aseptic Technique

The core objective of aseptic technique is to prevent the introduction of contaminants (bacteria, fungi, viruses, and chemical impurities) into cell cultures and reagents. This is achieved through two complementary approaches: creating a sterile operating environment and preventing the introduction of foreign microorganisms during handling and cultivation [31]. A key distinction exists between sterile technique, which aims to eliminate every potential microorganism, and aseptic technique, which focuses on maintaining a previously sterilized environment by not introducing contamination [4] [32]. For routine culture, this involves a mindset of constant vigilance, where every action is performed with the intention of preserving sterility.

The Comprehensive Aseptic Technique Checklist

The following checklist provides a structured framework for ensuring aseptic conditions before, during, and after routine culture procedures. Use it to standardize practices across your laboratory.

Table 1: Comprehensive Aseptic Technique Checklist for Routine Culture

| Category | Task | Completed (✓/✗) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Work Preparation | Confirm all necessary materials are available and sterilized. | |

| Perform appropriate hand hygiene (washing with soap and water). | ||

| Don appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) (lab coat, gloves). | ||

| Tie back long hair. | ||

| Work Area & BSC Setup | Ensure the Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) is in an area free from drafts and through traffic. | |

| Wipe the BSC work surface and all items with 70% ethanol before introduction. | ||

| UV sterilize the BSC for a minimum of 30 minutes pre-use (if applicable). | ||

| Run the BSC blower for at least 5 minutes before starting work. | ||

| Organize the work surface to be uncluttered, containing only essential items. | ||

| Reagents & Media | Sterilize all reagents, media, and solutions prepared in-lab via autoclaving or filtration. | |

| Wipe the outside of all bottles, flasks, and plates with 70% ethanol before placing in BSC. | ||

| Inspect reagents for cloudiness, floating particles, or unusual color; discard if contaminated. | ||

| Keep all containers capped when not in use. Store plates in sterile re-sealable bags. | ||

| Sterile Handling | Work slowly, deliberately, and mindfully. Avoid rapid movements that disrupt airflow. | |

| Flame-sterilize inoculating loops to red-hot before and after use; allow to cool. | ||

| Flame the necks of bottles and test tubes by passing them through a Bunsen burner flame. | ||

| Use only sterile glass or disposable plastic pipettes. Use each pipette only once. | ||

| Place caps or covers face-down on the work surface if they must be removed. | ||

| Avoid touching sterile pipette tips to non-sterile surfaces (e.g., bottle threads). | ||

| Minimize talking, singing, or whistling during procedures. | ||

| Post-Work Cleanup | Mop up any spillage immediately and wipe the area with 70% ethanol. | |

| Remove all items from the BSC and wipe the surface again with 70% ethanol. | ||

| UV sterilize the BSC for 5 minutes post-use (if applicable). | ||

| Properly dispose of all contaminated waste. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Aseptic Procedures

Protocol: Sterile Transfer Using an Inoculating Loop

This protocol is essential for transferring microorganisms between solid and liquid media while maintaining purity [33].

- Sterilize the Loop: Hold the handle of the wire loop close to the top. Sterilize the loop by heating it to red-hot in the roaring blue cone of a Bunsen burner flame. Heat the entire length of the wire gradually to prevent splattering [33].

- Cool the Loop: Allow the sterilized loop to cool for a few seconds in the sterile air near the flame. Do not wave it around or place it on a non-sterile surface [31].

- Sample the Culture: For a broth culture, briefly flame the neck of the tube. Insert the cooled loop and remove a loopful of culture. For a plate, lift the lid slightly, cool the loop by touching an empty area of agar, then touch a single colony.

- Inoculate: Transfer the sample to the new, sterile medium (e.g., streak onto an agar plate, inoculate a broth tube, or use a zigzag pattern on an agar slant) [31].

- Re-sterilize: Immediately after the transfer, re-sterilize the loop in the flame to destroy any remaining microorganisms before placing it down.

Protocol: Aseptic Pipetting and Liquid Handling

This protocol ensures sterile transfer of liquid cultures, media, and reagents [4] [33].

- Select Pipette: Use a sterile graduated or Pasteur pipette. Remove it from its wrapper by the end containing the cotton wool plug, touching as little of the shaft as possible.

- Attach Teat: Fit a sterile teat. It can be helpful to dip the teat first in sterile liquid to lubricate it.

- Aspirate Liquid: Hold the pipette like a pen. Squeeze the teat before placing the tip into the liquid to avoid introducing air bubbles. Gently release pressure to draw up the required volume, ensuring liquid does not wet the cotton plug [33].

- Transfer Liquid: Move the pipette to the receiving vessel. Flame the neck of the vessel if it is a bottle or tube. Dispense the liquid gently.

- Discard: Immediately after use, place the contaminated pipette into a nearby pot of disinfectant. Remove the teat only once the pipette is within the discard pot.

Protocol: Flaming the Neck of Bottles and Test Tubes

This procedure creates an upward convection current that prevents airborne contaminants from entering vessel openings [33].

- Loosen Cap: Loosen the cap of the bottle or tube so it can be removed easily with one hand.

- Remove Cap: Hold the vessel in your non-dominant hand. Remove the cap or cotton wool plug with the little finger of your dominant hand (curled towards the palm). Do not place the cap on the bench.

- Flame the Neck: Pass the neck of the vessel forwards and back through the hottest part of the Bunsen burner flame (above the inner blue cone). Do not hold it in place.

- Perform Procedure: While the neck is still warm, quickly perform the required procedure (e.g., pouring, pipetting).

- Recap: Flame the neck once more and replace the cap using the little finger. Turn the bottle, not the cap, to secure it.

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of actions required to establish and maintain an aseptic environment for routine culture, from preparation to final cleanup.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful aseptic culture relies on the consistent use of specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The table below details the core components of this toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Aseptic Culture

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol | Primary disinfectant for wiping down work surfaces, gloves, and the outside of containers introduced into the BSC [4] [33]. | More effective than higher concentrations due to slower evaporation, allowing more contact time with microbes. |

| Sterile Cell Culture Media | Provides essential nutrients, growth factors, and hormones to support cell growth and proliferation. | Must be pre-sterilized (typically by filtration). Check for cloudiness or color change before use, indicating potential contamination [4]. |

| Sterile Pipettes (Plastic/Glass) | For precise, sterile transfer of liquid cultures, media, and reagents. | Disposable plastic pipettes are single-use. Sterile glass pipettes must be re-sterilized by autoclaving after each use [4]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Forms a barrier between the researcher and biological materials, protecting both the culture and the personnel [4] [34]. | Includes lab coat, gloves, and safety glasses. Gloves should be changed frequently and if contaminated. |

| Inoculating Loops/Needles | Essential tools for transferring and streaking microbial cultures. | Must be sterilized by heating to red-hot in a Bunsen burner flame before and after every use to prevent cross-contamination [33]. |

| Bunsen Burner | Creates an updraft and provides a sterile zone for procedures like flaming loops and vessel necks [33]. | The flame should have a roaring blue cone. Work is performed in the sterile hot air surrounding the flame. |

| Disinfectant (e.g., 1% Virkon) | Used for decontaminating surfaces and for discarding contaminated liquids and equipment [33]. | A safer alternative to ethanol for student use; surface must remain wet for at least 10 minutes for effective disinfection. |

Mastering aseptic technique is not a one-time event but a continuous commitment to quality and precision in the cell culture laboratory. By systematically implementing the checklist, protocols, and principles outlined in this guide, researchers can build a robust defense against contamination. This diligence directly translates to more reliable data, reproducible experiments, and the efficient use of time and resources, thereby accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and drug development.

In cell culture, the integrity of experimental results is entirely dependent on the quality of the liquid handling techniques employed. Proper manipulation of liquids, media, and reagents through precise pipetting, careful pouring, and disciplined container management forms the first and most critical line of defense against contamination. These fundamental skills are essential for maintaining the sterility of the workspace, ensuring the viability of cell lines, and guaranteeing the reproducibility of scientific data [4]. This guide details the core principles and protocols for handling materials in a cell culture setting, framed within the broader context of aseptic technique essential for successful research and drug development.

Fundamental Principles of Aseptic Liquid Handling

The core objective of aseptic technique is to prevent microorganisms from the environment from contaminating sterile cultures, media, and reagents [4]. This is achieved by creating and maintaining barriers between sterile and non-sterile surfaces.

- Aseptic vs. Sterile Technique: It is crucial to distinguish between these two concepts. Sterilization is a process that destroys all microbial life, creating a state of absolute freedom from microorganisms (e.g., autoclaving). Aseptic technique, conversely, is the set of practices used to maintain sterility by preventing contaminants from contacting sterile materials during handling [2].

- The Sterile Field: The primary barrier is the biosafety cabinet (BSC) or laminar flow hood, which provides a HEPA-filtered, sterile airflow [2]. All manipulations with open containers should occur within this space. A properly maintained and disinfected workspace is fundamental; the working surface must be uncluttered and thoroughly wiped with 70% ethanol before and after work [4] [35].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Lab personnel must wear appropriate PPE—including a clean lab coat, gloves, and sometimes safety glasses—to minimize the introduction of contaminants from the body and clothing [4] [2]. Gloved hands should be wiped with 70% ethanol before working in the BSC.

Pipetting Techniques and Protocols

Pipetting is the most common method for transferring liquids in the cell culture lab. Accuracy and sterility are paramount.

Air Displacement Pipette Principles

Most laboratory pipettes are air displacement pipettes. They operate by moving a piston to create a vacuum that draws liquid into a disposable tip. A critical air cushion separates the piston from the liquid, preventing contamination of the pipette interior [36] [37]. The accuracy of this system can be affected by temperature, liquid density, and vapor pressure [38].

Forward and Reverse Pipetting

The choice between forward and reverse pipetting is determined by the physical properties of the liquid being handled. The table below provides a comparative overview.

Table 1: Comparison of Forward and Reverse Pipetting Techniques

| Feature | Forward Pipetting (Standard Mode) | Reverse Pipetting |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Aqueous solutions (buffers, diluted acids, culture media) [36] [39] | Viscous, foaming, or volatile liquids (glycerol, detergents, proteins, organic solvents) [36] [37] |

| Technique | 1. Press plunger to first stop.2. Aspirate liquid.3. Dispense by pressing to first stop, then press to second stop (blow-out) to expel residual liquid [36] [37]. | 1. Press plunger to second stop.2. Aspirate liquid (excess is drawn in).3. Dispense by pressing only to the first stop, leaving excess in the tip, which is then discarded [36] [38]. |

| Mechanism | Delivers the exact volume set on the pipette [37]. | Aspirates excess to compensate for liquid retained on the tip wall, ensuring accurate delivery of the set volume despite retention [36]. |

Aseptic Pipetting Protocol

The following workflow outlines the key steps for sterile pipetting within a biosafety cabinet. Adhering to this protocol minimizes the risk of contaminating your samples, reagents, and cultures.

Essential Pipetting Tips for Accuracy

- Pre-wetting: For volatile compounds or to improve accuracy, aspirate and expel the liquid 2-3 times before taking the sample for delivery. This saturates the air cushion within the tip, reducing evaporation [36] [39].

- Consistent Immersion: Immerse the tip just 2-3 mm below the liquid's surface for small volumes. Too little immersion can lead to air aspiration, while too much can cause liquid to cling to the tip's exterior [39].

- Smooth Operation: Use consistent plunger pressure and speed during aspiration and dispensing. Rapid movements can cause splashing, inaccuracies, and aerosol formation [39].

- Temperature Equilibrium: Allow pipettes, tips, and liquids to equilibrate to room temperature before use. Temperature differences cause expansion or contraction of the air cushion, leading to significant volume errors [36] [39] [38].

- Minimal Handling: Handle pipettes loosely and set them down in a stand when not in use. Body heat transferred to the pipette can affect the temperature of the air inside and lead to volume variations [39].

Pouring, Transfer, and Container Management

While pipetting is preferred for precision, pouring is sometimes necessary for larger volumes. Both activities require stringent container management.

Aseptic Pouring Protocol

Pouring is a higher-risk activity for contamination and should be performed with extreme care.

- Flaming: Before opening, briefly pass the neck of a glass bottle or flask through a Bunsen burner flame (if outside a BSC) or use an alcohol lamp. This creates an upward convection current that prevents airborne particles from falling into the container [2]. The cap should be held in the hand, facing down, and never placed on the bench [4].

- Controlled Pouring: Work slowly and deliberately. Pour against the inner neck of the receiving vessel to create a single stream and minimize splashing. Avoid pouring between vessels if sterile pipettes are available, as pouring creates more turbulence and aerosol exposure than pipetting [4].

Container Management Workflow

Proper handling of culture vessels, media bottles, and reagent containers is a continuous process throughout any laboratory procedure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Aseptic Handling

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol | The primary disinfectant for decontaminating work surfaces, the exterior of containers, gloved hands, and equipment. Its effectiveness is concentration-dependent [4] [2]. |

| Air Displacement Pipettes | The workhorse for accurate measurement and transfer of small liquid volumes (1 µL to 10 mL), used with sterile disposable tips for most aqueous solutions [36] [37]. |

| Sterile, Filtered Pipette Tips | Create an airtight seal with the pipette cone. Filter tips are especially important for preventing aerosol contamination of the pipette shaft when working with biological samples [36] [38]. |

| Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) | Provides a HEPA-filtered sterile work environment, protecting both the cell culture from environmental contaminants and the user from potential biohazards [4] [2]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Includes lab coats, gloves, and safety glasses. Forms a barrier to prevent contamination of cultures from the user and protects the user from hazardous materials [11] [4]. |

| Sterile Culture Media | Nutrient-rich solutions (e.g., DMEM, RPMI) formulated to support specific cell growth needs. Must be sterile and often supplemented with serum, antibiotics, and other factors [40]. |

| Sterile Reagents & Solutions | Includes trypsin for cell detachment, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for washing, and other specialized reagents. All must be sterilized and handled aseptically [4] [40]. |

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

- Pipette Calibration: Regular calibration is non-negotiable for data integrity. Pipettes should be calibrated every 3-12 months, depending on usage frequency and application criticality, following ISO 8655 standards [37] [38]. This typically involves gravimetric measurement (weighing water) to check dispensed volume accuracy [37].

- Contamination Monitoring: Routinely check cultures and reagents for signs of contamination. Bacterial contamination often manifests as sudden turbidity in the medium; fungal contamination appears as floating mycelial spheres or filaments; and mycoplasma contamination may cause subtle changes in cell growth and morphology without media clouding [2]. Any contaminated material should be immediately quarantined and decontaminated.

By integrating these detailed protocols for pipetting, pouring, and container management into daily practice, researchers and drug development professionals can establish a robust foundation of aseptic technique, thereby safeguarding their valuable cell cultures and ensuring the generation of reliable and reproducible scientific data.

Within the broader context of aseptic technique protocol research, the fundamental division between adherent and suspension cell cultures necessitates distinct methodological approaches. The core principle of successful cell culture lies in mimicking the in vivo environment, which for anchorage-dependent cells means providing a solid substrate, and for non-adherent cells, ensuring a homogenous liquid environment [41] [42]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols, framed within a thesis on aseptic techniques, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in adapting their methods for these specific cell types. The adherence to correct protocols is not merely a procedural requirement but a critical factor in maintaining cell health, functionality, and the integrity of experimental data, especially as the field advances toward more complex systems like cell and gene therapies and large-scale biomanufacturing [43] [41].

Fundamental Differences and Selection Criteria

Comparative Analysis of Culture Platforms