Overcoming Limited Batch Comparability: A Phase-Appropriate Roadmap for Biologics and Advanced Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the critical challenge of demonstrating product comparability with limited batch numbers.

Overcoming Limited Batch Comparability: A Phase-Appropriate Roadmap for Biologics and Advanced Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the critical challenge of demonstrating product comparability with limited batch numbers. As manufacturing processes for biologics, cell, and gene therapies evolve, changes are inevitable, yet the small batch sizes and inherent variability of these complex products make traditional comparability approaches impractical. This piece explores the foundational principles of a phase-appropriate and risk-based strategy, details methodological frameworks for study design and execution, offers troubleshooting and optimization tactics for real-world constraints, and outlines validation techniques to meet regulatory standards. By synthesizing current regulatory thinking and scientific best practices, this resource aims to equip scientists with the tools to build robust, defensible comparability packages that facilitate continued product development and ensure patient safety.

Understanding the Comparability Imperative: Why Limited Batches Pose a Unique Challenge

For researchers in drug development, demonstrating comparability is a critical regulatory requirement after making a manufacturing change. It is the evidence that ensures the biological product before and after the change is highly similar, with no adverse impact on the product's safety, purity, or potency [1]. The goal is not to prove the two products are identical, but that any differences observed do not affect clinical performance, thereby allowing manufacturers to implement improvements without needing to repeat extensive clinical trials [2] [1].

This guide provides targeted support for the unique challenge of conducting comparability studies with a limited number of batch numbers, where statistical power is low and variability can be a significant concern [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Comparability

Q1: What is the regulatory basis for demonstrating comparability? The FDA's guidance document, "Demonstration of Comparability of Human Biological Products, Including Therapeutic Biotechnology-derived Products," outlines the framework. It states that for manufacturing changes made prior to product approval, a sponsor can use data from nonclinical and clinical studies on the pre-change product to demonstrate that the post-change product is comparable, potentially avoiding the need for new clinical efficacy studies [1].

Q2: Our team only has 3 batches of the pre-change product. Is this sufficient for a comparability study? While low batch numbers present statistical challenges, they are a common reality in development. Sufficiency depends on the extent and robustness of your analytical data. The focus should be on employing orthogonal analytical methods and leveraging advanced statistical models tailored for small datasets to compensate for the limited numbers and ensure data robustness [2].

Q3: During a TR-FRET assay for potency, we see no assay window. What is the most common cause? The most common reason for a complete lack of assay window is an incorrect instrument setup. We recommend referring to instrument setup guides for your specific microplate reader. Verify that the correct emission filters are being used, as this is critical for TR-FRET assays [3].

Q4: What does a high Z'-factor tell us about our bioassay? The Z'-factor is a key metric for assessing the quality and robustness of an assay. An assay with a Z'-factor greater than 0.5 is considered to have an excellent separation band and is suitable for use in screening. It accounts for both the assay window (the difference between the maximum and minimum signals) and the data variation (standard deviation) [3].

Q5: Why might we see different EC50 values between our lab and a partner's lab using the same compound? A primary reason for differences in EC50 (or IC50) values between labs is often related to differences in the stock solutions prepared by each lab. Ensure consistency in the preparation, handling, and storage of all stock solutions [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Assay Window | Incorrect microplate reader setup or emission filters [3]. | Validate instrument setup using recommended guides and confirm filter specifications. |

| High Data Variability | Low batch numbers amplify normal process variability [2]. | Apply orthogonal analytical methods and advanced statistical models for small datasets [2]. |

| Inconsistent Potency Results | Inconsistent stock solution preparation or cell-based assay conditions [3]. | Standardize protocols for stock solutions and validate cell passage numbers and health. |

| Poor Z'-Factor | High signal noise or insufficient assay window [3]. | Optimize reagent concentrations and incubation times. Review protocol for consistency. |

The Comparability Study Workflow

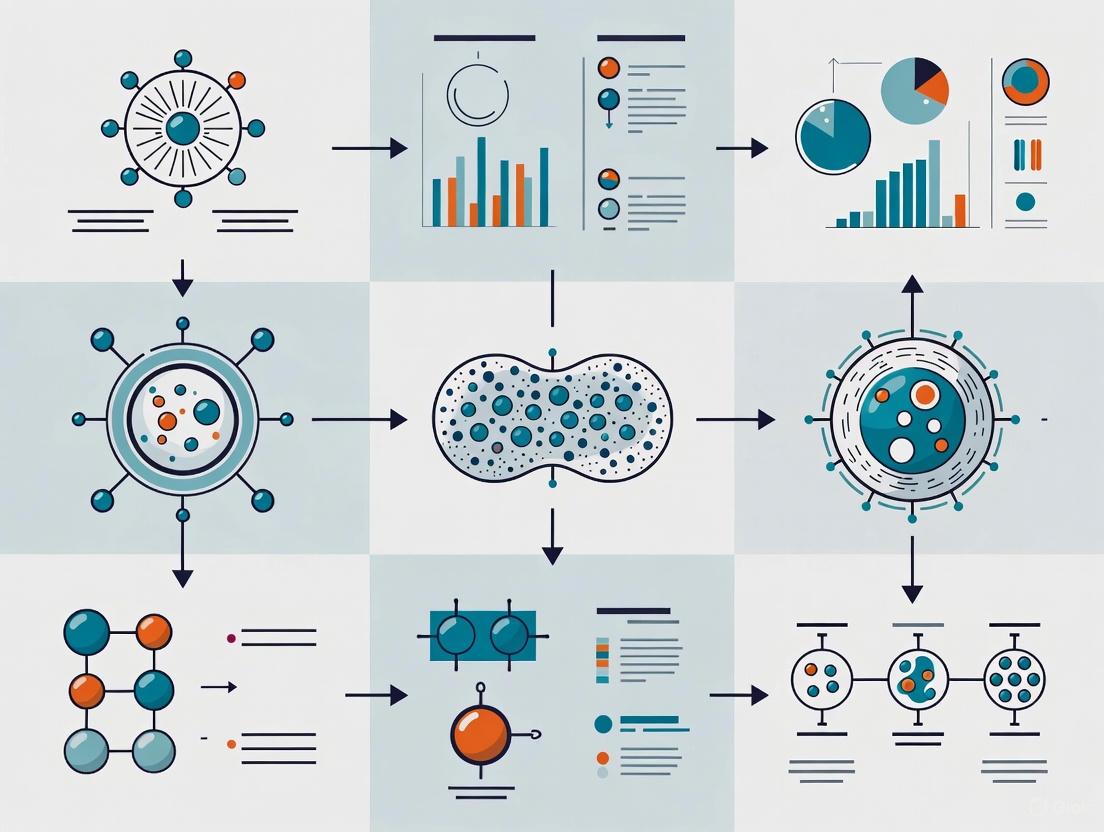

The following diagram outlines a strategic workflow for establishing comparability, emphasizing analytical rigor, especially when batch numbers are limited.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions in conducting robust comparability studies.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Comparability Studies |

|---|---|

| Fully Characterized Reference Standards | Serve as a benchmark for side-by-side analysis of pre-change and post-change products; critical for ensuring the consistency of analytical measurements [1]. |

| Orthogonal Analytical Methods | Techniques based on different physical or chemical principles (e.g., SEC, CE-SDS, MS) used together to comprehensively profile product attributes and confirm results [2]. |

| TR-FRET Assay Kits | Used for potency and binding assays; time-resolved fluorescence reduces background noise, providing a robust assay window for comparing biological activity [3]. |

| Validated Cell Lines | Essential for bioassays (e.g., proliferation, reporter gene assays) that measure the biological activity of the product, a key aspect of demonstrating functional comparability. |

| Stable Isotope Labels | Used in advanced mass spectrometry for detailed characterization of post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation) that may be critical for function. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section addresses frequently asked questions and provides guided troubleshooting for researchers navigating the complexities of product development with limited batch numbers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can we demonstrate product comparability after a necessary manufacturing process change, especially with high inherent variability in our starting materials?

Demonstrating comparability—proving product equivalence after a process change—is particularly difficult for complex products like cell therapies where "the product is the process" and full characterization is often impossible [4]. To address this:

- Implement a Robust Comparability Protocol: Before any change, establish a detailed, written plan that outlines the tests, studies, analytical procedures, and acceptance criteria to demonstrate that the change does not adversely affect the product's quality, safety, or efficacy [4].

- Focus on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Base your assessment on the physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that are critical to ensuring the desired product quality. Use historical and process development data to set meaningful acceptance criteria [4].

- Leverage Advanced Analytical Tools: Invest in orthogonal analytical methods and potent, mechanism-relevant potency assays that are capable of detecting meaningful quality changes, as these are most critical for assessing comparability [5] [4].

FAQ 2: Our small-batch production for a Phase I clinical trial is plagued by high costs and material loss. What strategies can we employ to improve efficiency?

Small-batch manufacturing for early-stage trials is inherently less cost-efficient and faces challenges like limited material availability and high risk of waste [6].

- Adopt Low-Loss Filling Technologies: Partner with CDMOs that offer filling lines specifically designed for small batches. For example, some innovative fillers can process batches of less than 1L with total product loss under 30 mL, preserving valuable product [7].

- Utilize Single-Use and Modular Systems: Implement single-use technologies and modular manufacturing units to enhance flexibility, reduce cross-contamination risk, and minimize downtime and validation efforts between batches [6].

- Engage a Flexible CDMO: Outsourcing to a specialized Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization (CDMO) can provide access to expert small-batch capabilities, advanced technologies, and shared resources, helping to control costs and mitigate risk [6].

FAQ 3: What is the best approach to manage the complexity that arises from offering a wide variety of product configurations?

Increasing product variety leads to significant complexity in manufacturing and supply chains. Simply counting the number of product variants is an insufficient measure of this complexity [8].

- Quantify Variety-Induced Complexity: Apply metrics from information theory, such as entropy-based measures, to better understand the structural complexity arising from the relations between the portfolio of optional components and the final product variants [8].

- Analyze with a Design Structure Matrix (DSM): Transform your product platform structure into a DSM to map the mutual relationships between functional requirements (product variants) and design parameters (components). This helps identify and manage the core sources of complexity [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Product Quality and Potency Between Small Batches

- Potential Cause 1: High variability in starting materials (e.g., donor cells). The variability of starting materials is one of the largest obstacles to consistent manufacturing, impacting both the quality and potency of the final product [5].

- Solution: Implement stronger donor selection and cell source characterization criteria. For critical materials, perform full genomic characterization to provide important safeguards [5].

- Potential Cause 2: Immature or inadequate analytical procedures. The field's analytical technologies are still maturing, making it challenging to reliably assess product consistency [5].

- Solution: Invest early in developing and qualifying analytical tools. Leverage Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring and control of critical manufacturing steps to ensure consistency [5].

- Potential Cause 3: Manual processes prone to human error. Small-batch production often involves manual operations due to the need for flexibility, which increases the risk of inconsistencies [6].

- Solution: Where possible, introduce automation or mechanization. Automating a manual process enhances repeatability and reduces risk, while mechanization can achieve performance beyond human capability [4].

Problem: Navigating Divergent Global Regulatory Requirements for a Novel Complex Product

- Potential Cause: Lack of global regulatory harmonization. There is an absence of global consensus on definitions, approval pathways, and technical standards for complex products like cell and gene therapies, creating complexity for developers [5].

- Solution:

- Engage Early with Regulators: Seek early and transparent communication with regulatory authorities to anticipate expectations and align development approaches [5].

- Advocate for Regulatory Pilots: Support the creation of "regulatory sandboxes"—controlled environments where regulators and developers can experiment with new assessment methods for manufacturing changes under close supervision [5].

- Utilize Cross-Referencing Tools: Develop a crosswalk (comparison) of expedited pathways across different agencies to identify opportunities for convergence and streamline regulatory planning [5].

- Solution:

The table below consolidates key quantitative challenges and metrics related to managing complex products with small batch sizes.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data on Complex Product and Small-Batch Challenges

| Category | Metric / Challenge | Data / Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Complexity | Metric for variety-induced complexity | The number of product variants alone is an insufficient measure. Entropy-based metrics and Design Structure Matrix (DSM) analysis are more reliable. | [8] |

| Small-Batch Manufacturing | Acceptable product loss in fill-finish | For batches <1L, specialized low-loss fillers can achieve total product loss (line, filter, transfer) of <30 mL. Batches with a bulk volume as low as 100 mL are feasible. | [7] |

| Drug Development Pipeline | Number of gene therapy drugs in development (2025) | Over 2,000 drugs in development, with only 14 on the market. Highlights the volume of products in early, small-batch phases. | [7] |

| Therapeutic Area Cost Impact | Price reduction of complex generics vs. branded drugs | Complex generics can provide a 40-50% reduction in price compared to their branded counterparts. | [9] |

| Manufacturing Cost Impact | Cost increase due to product variety (automotive industry) | Increased product variety can lead to a total cost increase of up to 20%. | [8] |

Experimental Protocol: Demonstrating Process Comparability After a Manufacturing Change

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for conducting a comparability study following a defined change in the manufacturing process of a complex biological product (e.g., a cell-based therapy).

1. Objective: To generate sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the product manufactured after a process change is highly similar to the pre-change product in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy, with no adverse impact.

2. Pre-Study Requirements:

- Define the Change: Clearly document the nature, scope, and rationale for the manufacturing process change.

- Establish a Comparability Protocol: As per FDA guidance, prepare a pre-approved, detailed plan outlining the tests, studies, analytical procedures, and, most importantly, the pre-defined acceptance criteria [4].

- Risk Assessment: Conduct a risk-based assessment to identify which Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) are most likely to be impacted by the change [4].

3. Methodology:

- Study Design:

- Arm 1: Product manufactured using the established, pre-change process (Reference).

- Arm 2: Product manufactured using the new, post-change process (Test).

- A minimum of 3 batches per arm is recommended to account for process variability, though this may be adapted for small-batch scenarios.

- Sample Analysis:

- Test both Reference and Test batches against a panel of quality control assays.

- Key Assays to Include:

- Identity/Purity: Flow cytometry, HPLC, etc., as relevant.

- Potency: A biologically relevant assay that reflects the product's mechanism of action. This is considered the most critical assay for comparability [4].

- CQAs: All attributes deemed critical for product quality, safety, and function.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the Test data against the pre-defined acceptance criteria and the historical data range of the Reference product.

- Use appropriate statistical methods (e.g., equivalence testing) to determine if observed differences are within the justified, acceptable range of variability.

- Any significant differences must be investigated and justified in terms of potential impact on safety and efficacy.

4. Outcome:

- Successful Comparability: If all data meet the pre-defined acceptance criteria, the products are deemed comparable, and the new process can be implemented.

- Failed Comparability: If acceptance criteria are not met, further investigation, process optimization, and potentially additional non-clinical or clinical studies may be required before the change can be approved [4].

Process Visualization: Comparability Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in a comparability assessment following a manufacturing change.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table lists key reagents and materials critical for the development and characterization of complex biological products, especially in a small-batch context.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Complex Product Development

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Cell Banks | High-quality, well-characterized starting cell banks are foundational. Starting with research-grade plasmids and establishing GMP banks early lays a foundation for faster transitions and cost-effective scaling, improving product consistency [5]. |

| Research-Grade Plasmids | Used in early development and engineering runs to build the data needed to support process changes and scale-up without consuming costly GMP-grade materials [5]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Tools | A suite of tools for real-time monitoring and control of critical process parameters during manufacturing. Enables better control over consistency and quality of complex products with inherent variability [5]. |

| Advanced Analytical Assays (e.g., for Potency) | Complex bioassays that measure the biological activity of the product and reflect its mechanism of action. These are the most critical assays for assessing comparability and detecting impactful variations [4]. |

| Single-Use Bioreactors / Manufacturing Components | Disposable equipment used in small-batch manufacturing to enhance flexibility, reduce cleaning validation, and lower the risk of cross-contamination between batches [6]. |

| Modular Manufacturing Platforms | Flexible, scalable production systems that allow for efficient small-batch production and can be adapted quickly to process changes or different product specifications [6]. |

Foundational Concepts: Understanding Comparability and Batch Effects

What is the fundamental principle of ICH Q5E, and why is it critical for biological products?

ICH Q5E provides the framework for assessing comparability of biological products before and after manufacturing process changes. Its fundamental principle is to establish that pre- and post-change products have highly similar quality attributes, and that the manufacturing change does not adversely impact the product's quality, safety, or efficacy [10]. This is particularly critical for biotechnological/biological products due to their inherent complexity and sensitivity to manufacturing process variations.

How do "batch effects" relate to manufacturing process changes in regulatory science?

Batch effects are technical variations introduced due to changes in experimental or manufacturing conditions over time, different equipment, or different processing locations [11]. In the context of manufacturing process changes, these effects represent unwanted technical variations that can confound the assessment of true product quality. If uncorrected, they can lead to misleading conclusions about product comparability, potentially hindering biomedical discovery if over-corrected or creating misleading outcomes if uncorrected [11].

What profound risks do batch effects pose in regulatory decision-making?

Batch effects can act as a paramount factor contributing to irreproducibility, potentially resulting in:

- Retracted articles and invalidated research findings

- Economic losses

- Incorrect classification outcomes affecting patient treatment decisions

- Misleading conclusions about product quality and performance [11]

In one documented case, batch effects from a change in RNA-extraction solution resulted in incorrect classification for 162 patients, 28 of whom received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy regimens [11].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Scenarios

Troubleshooting Scenario: Limited Batch Numbers in Comparability Studies

Table 1: Troubleshooting Limited Batch Scenarios

| Challenge | Root Cause | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient statistical power | Small sample size (limited batches) | Leverage historical data and controls; employ Bayesian methods |

| Inability to distinguish batch from biological effects | Confounded study design | Implement randomized sample processing; balance experimental groups across batches |

| High technical variability masking true product differences | Minor treatment effect size compared to batch effects | Enhance analytical method precision; implement robust normalization procedures |

| Difficulty determining if detected changes are process-related | Inability to distinguish time/exposure effects from batch artifacts | Incorporate additional control points; use staggered study designs |

Diagnostic Framework: Is a Batch Effect Significant Enough to Require Correction?

When facing potential batch effects in limited batch scenarios, apply this diagnostic workflow:

Experimental Protocol: Batch Effect Assessment in Limited Batch Environments

Objective: Systematically identify and quantify batch effects when batch numbers are limited Materials: Multi-batch dataset, historical controls, appropriate analytical tools

Visual Assessment Phase

- Generate PCA scatterplots coloring samples by batch

- Create hierarchical clustering dendrograms

- Visualize using t-SNE/UMAP projections

Quantitative Assessment Phase

- Apply k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET) to measure local batch mixing

- Calculate average silhouette widths for batch separation

- Perform differential expression analysis between batches

Statistical Decision Phase

- Determine if batch variance exceeds biological variance of interest

- Assess whether batch is confounded with outcome variables

- Evaluate statistical power for batch effect correction

Correction Implementation Phase

- Select appropriate batch effect correction algorithm (BECA)

- Apply chosen correction method

- Validate correction effectiveness using above metrics

Table 2: Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs) for Different Data Types

| Data Type | Recommended BECAs | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk genomics | ComBat, limma | Established methods, handles small sample sizes | May over-correct with limited batches |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | BERMUDA, scVI, Harmony | Designed for complex single-cell data | Requires substantial cell numbers per batch |

| Proteomics | Combat, SVA adaptations | Handles missing data common in proteomics | Less developed for new proteomics platforms |

| Multi-omics | MDUFA, cross-omics integration | Integrates multiple data types simultaneously | Complex implementation, emerging field |

FAQ: Addressing Common Technical Challenges

How should we approach comparability assessment when we have only 2-3 batches post-manufacturing change?

With limited batches, employ a weight-of-evidence approach combining:

- Extensive characterization using orthogonal analytical methods

- Leveraging historical data and controls as additional reference points

- Implementing advanced statistical methods like Bayesian approaches that can incorporate prior knowledge

- Focusing on critical quality attributes with known clinical relevance

Batch effects in Cell and Gene Therapy (CGT) products commonly arise from:

- Reagent variability: Different lots of fetal bovine serum (FBS), enzymes, growth factors

- Process parameters: Variations in cell culture duration, transduction efficiency, purification methods

- Analytical timing: Differences in sample processing time prior to analysis

- Operator techniques: Different technical staff performing procedures

- Equipment variations: Different instruments or maintenance states

How does the new FDA guidance for CGT products in small populations address limited batch challenges?

The FDA's 2025 draft guidance on "Innovative Designs for Clinical Trials of Cellular and Gene Therapy Products in Small Populations" provides recommendations for:

- Alternative clinical trial designs suitable for small populations

- Innovative endpoint selection strategies

- Generating meaningful clinical evidence despite limited patient numbers

- Leveraging biomarkers and surrogate endpoints

- Using adaptive designs that maximize information from limited data [12]

When should we consider a study redesign rather than statistical batch correction?

Consider study redesign when:

- Batch effects are completely confounded with biological variables of interest

- The number of batches is insufficient for reliable statistical correction

- Batch effects are so substantial they overwhelm biological signals

- Critical control samples are missing across batches

- The cost of incorrect conclusions outweighs the cost of study repetition

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Batch Effect Mitigation

| Reagent/ Material | Function | Batch Effect Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference standards | Analytical calibration | Use same lot across all batches; characterize extensively |

| Cell culture media | Support cell growth | Pre-qualify multiple lots; use large lot sizes |

| Fetal bovine serum (FBS) | Cell growth supplement | Pre-test and reserve large batches; document performance |

| Enzymes (e.g., trypsin) | Cell processing | Quality check multiple lots; establish performance criteria |

| Critical reagents | Specific assays | Characterize and reserve sufficient quantities |

| Control samples | Process monitoring | Include in every batch; use well-characterized materials |

| Calibration materials | Instrument performance | Use consistent materials across all experiments |

Advanced Methodologies: Deep Learning Approaches for Batch Effect Correction

Emerging Deep Learning Solutions for Complex Batch Effects

With the advent of more complex data types in CGT development, deep learning approaches are emerging as powerful tools for batch effect correction:

Autoencoder-based Methods: These artificial neural networks learn complex nonlinear projections of high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional embedded spaces representing biological signals while removing technical variations [13].

Transfer Learning Approaches: Methods like BERMUDA use deep transfer learning for single-cell RNA sequencing batch correction, enabling discovery of high-resolution cellular subtypes that might be obscured by batch effects [13].

Integrated Solutions: Newer algorithms simultaneously perform batch effect correction, denoising, and clustering in single-cell transcriptomics, providing comprehensive solutions for complex CGT data [13].

Implementation Workflow for Advanced Batch Effect Correction

Regulatory Strategy: Integrating ICH Q5E with Modern CGT Development

Implementing a Risk-Based Comparability Assessment

For CGT products with limited batch numbers, adopt a risk-based approach that:

- Identifies Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Focus on attributes with potential impact on safety and efficacy

- Leverages Orthogonal Methods: Use multiple analytical techniques to compensate for limited batches

- Incorporates Historical Data: Where appropriate, use data from similar products or processes

- Implements Continuous Monitoring: Collect data post-implementation to confirm comparability assessment

Documentation Strategies for Limited Batch Scenarios

When batch numbers are limited, comprehensive documentation becomes critical:

- Detailed rationale for sample size and statistical approaches

- Complete characterization of all materials and reagents

- Thorough investigation of any outliers or unexpected results

- Clear explanation of risk mitigation strategies

- Plan for post-implementation data collection and assessment

By applying these structured troubleshooting approaches, leveraging appropriate technical solutions, and implementing robust regulatory strategies, researchers can successfully navigate comparability assessment challenges even when faced with limited batch scenarios in CGT development.

Troubleshooting Guide: CPP Deviations and CQA Impact

Q: What should I do if my CPPs are in control, but my CQAs are still out of specification?

This indicates that your current control strategy may be incomplete. The measurable CQAs you are monitoring might not be fully predictive of the product's true quality and biological activity [14].

- Investigate Unmeasured CQAs: The product's critical quality may be defined by attributes you are not currently measuring. Re-evaluate the product's Mechanism of Action (MOA) to identify potential CQAs that your assays are not capturing [15] [14].

- Challange Your Potency Assay: A poorly correlated or insensitive potency assay is a common culprit. The FDA has issued complete response letters specifically due to a lack of scientific rationale linking potency measurements to biological activity [14]. Develop a matrix of candidate potency assays that reflect the intended MOA[s [15].

- Review Your Process Parameters: A CPP you have not identified as critical may be affecting an unmeasured CQA. Deepen your process understanding through risk assessment and additional design of experiments (DoE) studies [16] [17].

Q: How can I demonstrate comparability with a very limited number of batches?

Limited batch numbers are a common challenge in cell and gene therapy. A successful strategy involves leveraging strong scientific rationale and proactive planning [15].

- Adopt a Prospective Approach: Where possible, plan manufacturing changes and generate "split-stream" data by running the old and new processes side-by-side, even with a small number of batches. This is often more robust than retrospective comparison [15].

- Focus on a Science-Driven Narrative: Use existing knowledge of your product's CQAs, MOA, and process to build a strong comparability narrative. Regulators expect a data-driven, scientifically justified proposal [15].

- Utilize All Available Data: Incorporate data from all stages of development. Even data from research or non-clinical batches can help establish a baseline for variability and support your narrative [15].

- Employ Statistical Science: Choose statistical methods wisely. For small sample sizes, equivalence testing with pre-defined acceptance criteria based on biological relevance is often more appropriate than tests relying solely on statistical power [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the fundamental relationship between a CPP and a CQA? A critical process parameter (CPP) is a variable process input (e.g., temperature, pH) that has a direct impact on a critical quality attribute (CQA) [16] [18] [17]. A CQA is a physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological property (e.g., potency, purity) that must be controlled to ensure product quality [14] [17]. Controlling CPPs within predefined limits is how you ensure CQAs meet their specifications [17].

Q: Are CQAs fixed throughout the product lifecycle? No. CQAs are not always fully known at the start of development and are typically refined as product and process knowledge increases [14]. As you gain a better understanding of the product's Mechanism of Action (MOA) through clinical trials, you can refine your CQAs, particularly your potency assays, to ensure they are truly predictive of clinical efficacy [15] [14].

Q: What is the role of Quality Assurance (QA) in managing CPPs and CQAs? Quality Assurance (QA) has an oversight role to ensure that CPPs and CQAs are properly identified, justified, and controlled [17]. QA reviews and approves the risk assessments, process validation protocols, and control strategies related to CPPs and CQAs. They also ensure deviations are investigated and that corrective actions are effective [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions in developing and controlling a bioprocess, particularly for complex modalities like cell and gene therapies.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Bioprocess Sensors (pH, DO, pCO₂) [16] | In-line or on-line monitoring of Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) in real-time within bioreactors to ensure process control [16]. |

| Potency Assay Reagents [15] [14] | Used to develop and run bioassays that measure the biological activity of the product, which is a crucial CQA linked to the mechanism of action [15] [14]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Supplements [14] | Provides the nutrients and environment for cell growth and production. Their quality and composition are vital raw materials that can impact both CPPs and CQAs [14]. |

| Surface Marker Antibodies [14] | Used in flow cytometry to monitor cell identity and purity, which are common CQAs for cell therapy products like MSCs [14]. |

| Differentiation Induction Kits (e.g., trilineage) [14] | Used to assess the differentiation potential of stem cells, a standard functional CQA for certain cell therapies [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Designing a Comparability Study

Objective: To demonstrate that a product manufactured after a process change (e.g., scale-up, raw material change) is highly similar to the product from the prior process, with no adverse impact on safety or efficacy [15].

Methodology:

Define Scope & Risk Assessment:

- Clearly describe the manufacturing change.

- Perform a risk assessment to identify which CQAs and CPPs have a high likelihood of being impacted by the change [15].

Develop a Study Protocol:

Execute Analytical Testing:

- Test pre-change and post-change batches for a comprehensive panel of CQAs. ICH Q5E recommends testing for identity, purity, potency, and safety [15].

- A side-by-side (split-stream) analysis is preferred over a retrospective comparison [15].

- Key Focus on Potency: Employ a potency assay that is relevant to the product's known or postulated MOA. The assay should be able to detect differences in biological activity [15] [14].

Data Analysis & Statistical Evaluation:

- Use statistical methods appropriate for the data set and sample size. The goal is to show "comparability" and not just "no significant difference," which can be a function of low statistical power [15].

- Determine if any observed differences are statistically significant and, more importantly, biologically relevant [15].

Prepare the Comparability Report:

- Document all data and the scientific rationale concluding that the products are comparable. The report should tell a clear story for regulator review [15].

CQA and CPP Relationships Across the Product Lifecycle

The table below summarizes how the focus on CQAs and CPPs evolves from early development to commercial manufacturing.

| Product Lifecycle Stage | CQA Focus | CPP Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Early Development (Pre-clinical, Phase 1) | • Identification of potential CQAs based on limited MOA knowledge and literature [14].• Use of general, often non-specific, potency assays [14]. | • Identification of key process parameters through initial experimentation (DoE) [16].• Establishing initial, wide control ranges. |

| Late-Stage Development (Phase 2, Phase 3) | • Refinement of CQAs, especially potency, based on clinical data [15] [14].• Linking CQAs to clinical efficacy. | • Narrowing of CPP operating ranges based on increased process understanding [16].• Process validation to demonstrate consistent control of CPPs. |

| Commercial Manufacturing | • Ongoing monitoring of validated CQAs to ensure consistent product quality [18]. | • Strict control of CPPs within validated ranges to ensure the process remains in a state of control [17]. |

Process Control and Quality Relationship

Comparability Study Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Batch Variability

Q1: Our bioequivalence (BE) study failed because the Reference product batches were not equivalent. What went wrong? This is a documented phenomenon. A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that different batches of the same commercially available product (Advair Diskus 100/50) can fail the standard pharmacokinetic (PK) BE test when compared to each other. In one study, all pairwise comparisons between three different batches failed the statistical test for bioequivalence, showing that batch-to-batch variability can be a substantial component of total variability [19] [20].

Q2: Why is this a critical problem for generic drug development? The current regulatory framework for BE studies typically assumes that a single batch can adequately represent an entire product. When substantial batch-to-batch variability exists, the result of a standard BE study becomes highly dependent on the specific batches chosen for the Test (T) and Reference (R) products. This means a study might show bioequivalence with one set of batches but fail with another, making the result unreliable and not generalizable [19] [21].

Q3: What is the core statistical issue? In standard single-batch BE studies, the uncertainty in the T/R ratio estimate does not account for the additional variability introduced by sampling different batches. The 90% confidence interval constructed in the analysis only reflects within-subject residual error and ignores the variance between batches. When batch-to-batch variability is high, this leads to an artificially narrow confidence interval that overstates the certainty of the result [19] [21].

Q4: Are there study designs that can mitigate this problem? Yes, researchers have proposed multiple-batch approaches. Instead of using a single batch for each product, several batches are incorporated into the study design. The statistical analysis can then be adapted to account for batch variability, for instance by treating the "batch" effect as a random factor in the statistical model, which provides a more generalizable conclusion about the products themselves [21].

Q5: For which types of drugs is this most problematic? Batch-to-batch variability poses significant challenges for the development of generic orally inhaled drug products (OIDPs), such as dry powder inhalers (DPIs). The complex interplay between formulation, device, and manufacturing processes for these locally acting drugs can lead to PK variability between batches, complicating BE assessments [20] [21].

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: Methodologies for Limited Batch Research

When your research is confounded by limited batch comparability, the following experimental protocols and methodologies can provide more robust conclusions.

1. Protocol: Multiple-Batch Pharmacokinetic Bioequivalence Study

This design incorporates multiple batches directly into the clinical study to improve the reliability of the BE assessment without necessarily increasing the number of human subjects [21].

- Objective: To determine bioequivalence between Test (T) and Reference (R) products while accounting for batch-to-batch variability.

- Study Design: A two-period, randomized crossover design arranged in cohorts.

- Subjects are divided into

ccohorts. - Each cohort receives a single, unique batch of T and a single, unique batch of R in random order (TR or RT).

- Different cohorts receive different batches of T and R.

- The total number of batches assessed per product is equal to the number of cohorts (

c) [21].

- Subjects are divided into

- Key Parameters:

c: Number of cohorts (and batches per product)m: Number of subjects per sequence per cohort- Total subjects,

N=2 * m * c

- Statistical Analysis Models: The performance and interpretation depend on how batch effects are handled in the analysis of variance (ANOVA) [21]:

| Approach | Description | Statistical Question | Handles Batch Sampling Uncertainty? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Batch Effect | Batch included as a random factor in the ANOVA. | Are the T and R products bioequivalent? | Yes |

| Fixed Batch Effect | Batch included as a fixed factor in the ANOVA. | Are the selected T batches bioequivalent to the selected R batches? | No |

| Superbatch | Data from multiple batches are pooled; batch identity is ignored in ANOVA. | Are the selected T batches bioequivalent to the selected R batches? | No |

| Targeted Batch | An in vitro test is used to select a median batch of each product for a standard BE study. | Are the selected T batches bioequivalent to the selected R batches? | No |

The following workflow illustrates the decision process for selecting and implementing these methodologies:

2. Quantitative Data on Batch-to-Batch Variability

The following table summarizes key PK data from a clinical study that investigated three different batches of Advair Diskus 100/50, with one batch (Batch 1) replicated. The data illustrate the magnitude of variability that can exist between batches of a marketed product [19].

Table 1: Pharmacokinetic Data Demonstrating Batch-to-Batch Variability for Advair Diskus 100/50 (FP) [19]

| PK Parameter | Batch 1 - Replicate A | Batch 1 - Replicate B | Batch 2 | Batch 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (pg/mL) | 44.7 | 45.4 | 69.2 | 58.9 |

| AUC(0-t) (h·pg/mL) | 178 | 177 | 230 | 220 |

- Key Finding: The replicated batch (A vs. B) showed consistent results, confirming the study's precision. However, Batches 2 and 3 showed notably higher systemic exposure (Cmax and AUC) compared to Batch 1, with differences large enough to cause bio-inequivalence in a standard BE test [19]. The between-batch variance was estimated to be ~40–70% of the total residual error [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

When designing studies to address batch variability, the following statistical and methodological "reagents" are essential.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Methods for Batch Variability Research

| Item | Function/Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Replicate Crossover Design | A study design where the same formulation (often the Reference) is administered to subjects more than once. | Allows for direct estimation of within-subject, within-batch variability and provides more data points without increasing subject numbers [22] [23]. |

| Statistical Assurance Concept | A sample size calculation method that integrates the power of a trial over a distribution of potential T/R-ratios (θ), rather than a single assumed value. | Provides a more realistic "probability of success" by formally accounting for uncertainty about the true T/R-ratio before the trial [24]. |

| Batch Effect Adjustment Methods | Statistical techniques (e.g., using the batchtma R package) to adjust for non-biological variation introduced by different batches or processing groups. |

Critical for retaining "true" biological differences between batches while removing technical artifacts. The choice of method (e.g., simple means, quantile regression) depends on the data structure and goals [25]. |

| In Vitro Bio-Predictive Tests | Physicochemical tests (e.g., aerodynamic particle size distribution) used to screen batches and select representative ones for clinical studies. | A well-established in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is required for this approach to be valid and predictive of clinical performance [20] [21]. |

Building Your Comparability Protocol: A Phase-Appropriate and Risk-Based Blueprint

Crafting a Prospective Study Protocol with Predefined Acceptance Criteria

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is a prospective comparability study design recommended over a retrospective one?

A prospective study is designed before implementing a manufacturing change. Participants are identified and observed over time to see how outcomes develop, establishing a temporal relationship between exposures and outcomes [26]. In comparability research, a prospective design is recommended because it de-risks delays in clinical development. It typically involves split-stream and side-by-side analyses of material from the old and new processes. While it may require more resources, it does not typically require formal statistical powering, unlike retrospective studies [15].

FAQ 2: What are the most critical elements to define in a prospective comparability protocol?

Your protocol should clearly define the following elements before initiating the study:

- Analytical Methods: A matrix of candidate potency assays that reflect the product's mechanism of action (MOA) is critical [15].

- Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Identity, strength, purity, and potency should be assessed [15].

- Predefined Acceptance Criteria: Establish quality ranges or equivalence ranges for each attribute, ensuring they are tied to biological meaning and not just statistical significance [15].

- Statistical Approach: The choice of statistical methods (e.g., quality range vs. equivalence testing) must consider data normality, paired/unpaired analysis, and statistical power [15].

FAQ 3: Our study yielded a statistically significant difference. Does this mean the processes are not comparable?

Not necessarily. A key principle is that statistically significant differences may not be biologically meaningful. The clinical impact of the difference must be evaluated. Your acceptance criteria should be based on a risk assessment that determines the likelihood of an impact on product safety and effectiveness. The finding necessitates a thorough, science-driven investigation to determine the true impact of the change [15].

FAQ 4: What is the primary cause of irreproducibility in comparability studies, and how can it be avoided?

Batch effects are a paramount factor contributing to irreproducibility. These are technical variations introduced due to changes in experimental conditions, reagents, or equipment over time [27]. To avoid them:

- Plan Proactively: Save sufficient product retains throughout development to support future analytical testing [15].

- Control Reagents: Be aware that reagent variability (e.g., different batches of fetal bovine serum) can invalidate results [27].

- Use Correction Methods: In omics data, employ batch effect correction algorithms (BECAs), especially when sample size is sufficient (e.g., including principal components in linear models) [28].

Common Experiment Discrepancies and Resolutions

| Issue | Possible Cause | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to establish comparability | Flawed study design; confounded batch effects; insufficient statistical power [27]. | Perform a proactive risk assessment; ensure sufficient sample size and use a prospective design; correct for known batch effects [15] [27]. |

| Statistically significant but biologically irrelevant difference | Acceptance criteria based solely on statistical power without linkage to biological relevance [15]. | Base acceptance criteria for each attribute on biological meaning and a science-driven risk assessment [15]. |

| Inability to reproduce key results | Changes in reagent batches or other uncontrolled technical variations (batch effects) [27]. | Implement careful experimental design to minimize batch effects; use retains from previous product batches for side-by-side testing [15] [27]. |

| High variability in potency assay | Potency assay not sufficiently robust or not reflective of the MOA [15]. | Invest early in developing a matrix of candidate potency assays; select the most robust one for the final specification [15]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for a Prospective Comparability Study

Objective: To demonstrate the comparability of a cellular or gene therapy product before and after a specific manufacturing process change.

Methodology: This is a prospective, side-by-side analysis of multiple batches produced from the old (original) and new (changed) manufacturing processes.

Workflow:

- Risk Assessment: Identify potential impacts of the manufacturing change on product CQAs, safety, and efficacy [15].

- Protocol Finalization: Define the specific CQAs, analytical methods, statistical approach, and predefined acceptance criteria [15].

- Batch Manufacturing: Generate a sufficient number of batches (N) using both the old and new processes.

- Side-by-Side Testing: Analyze all batches using the battery of methods defined in the protocol. Testing should include, but is not limited to, the assays listed in the table below.

- Data Analysis: Compare the data from the new process batches against the predefined acceptance criteria, which are often derived from the historical data of the old process [15].

- Conclusion: Determine if the data demonstrate comparability or if further investigation or process optimization is required.

Key Experiments and Analytical Methods

The table below summarizes the essential quality attributes and examples of methods used to assess them in a comparability study [15].

| Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) | Example Analytical Methods | Function in Comparability Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | Flow cytometry, PCR, Immunoassay | Confirms the presence of the correct therapeutic entity (e.g., cell surface markers, transgene). |

| Potency | Cell-based bioassay, Cytokine secretion assay, Enzymatic activity assay | Measures the biological activity linked to the product's Mechanism of Action (MOA); considered a critical component. |

| Purity/Impurities | Viability assays, Endotoxin testing, Residual host cell protein/DNA analysis | Determines the proportion of active product and identifies/quantifies process-related impurities. |

| Strength (Titer & Viability) | Cell counting, Vector genome titer, Infectivity assays | Quantifies the amount of active product per unit (e.g., viable cells per vial, vector genomes per mL). |

Visual Workflow: Prospective Comparability Study

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function in Comparability Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard | A well-characterized batch of the product used as a biological benchmark for all comparative assays to ensure consistency and accuracy [15]. |

| Characterized Cell Banks | Master and Working Cell Banks with defined characteristics ensure a consistent and reproducible source of cells, minimizing upstream variability [15]. |

| Critical Reagents | Key antibodies, enzymes, growth factors, and culture media. Their quality and consistency are vital; batch-to-batch variations can introduce significant batch effects [27]. |

| Validated Assay Kits/Components | Analytical test kits (e.g., for potency, impurities) that have been validated for robustness, accuracy, and precision to reliably detect differences between products [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Managing Limited Batch Numbers

Q1: With only 2-3 early-stage batches available, which analytical techniques provide the most meaningful comparability data? A1: For limited batches (n=2-3), prioritize Orthogonal Multi-Attribute Monitoring:

- Intact Mass Analysis (MS): Confirms primary structure

- Peptide Mapping (LC-MS/MS): Identifies post-translational modifications

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC-HPLC): Quantifies aggregates and fragments

- Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX-HPLC): Assesses charge variants These techniques provide a multi-dimensional comparability assessment with high information yield per batch.

Q2: How do we determine if observed analytical differences are significant when we have low statistical power? A2: Implement a Tiered System for data evaluation:

- Tier 1 (Quality Ranges): For critical quality attributes (CQAs) with known clinical impact

- Tier 2 (Acceptance Criteria): For attributes with potential impact

- Tier 3 (Descriptive): For characterization attributes

Table: Tiered Approach for Limited Batch Comparison

| Tier | Attribute Type | Statistical Approach | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CQAs with clinical impact | ±3σ of historical data | Tight, based on safety margins |

| 2 | Potential impact | ±3σ or % difference | Moderate, process capability |

| 3 | Characterization | Visual comparison | Qualitative assessment |

FAQ: Method Transitions

Q3: When transitioning from research-grade to GMP-compliant methods, how do we maintain comparability with limited data? A3: Execute a Method Bridging Study:

- Analyze the same 2-3 batches with both old and new methods

- Establish correlation coefficients for key attributes

- Define equivalence margins based on method precision

- Document any systematic biases for future reference

Table: Method Bridging Acceptance Criteria

| Parameter | Minimum Requirement | Target Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation (r) | >0.90 | >0.95 |

| Slope of regression | 0.80-1.25 | 0.90-1.10 |

| % Difference in means | <15% | <10% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Accelerated Stability for Comparability

Purpose: Assess comparability of stability profiles with limited batches.

Materials:

- Test articles: 2-3 batches each of reference and test material

- Storage conditions: 5°C, 25°C/60% RH, 40°C/75% RH

- Timepoints: 0, 1, 3, 6 months

Methodology:

- Prepare aliquots for each timepoint/condition combination

- Store samples in controlled stability chambers

- At each timepoint, analyze using the orthogonal methods from FAQ A1

- Calculate degradation rates and compare between batches using pairwise statistics

Analysis:

- Plot degradation profiles for each CQA

- Calculate similarity of slopes using equivalence testing

- Establish 90% confidence intervals for differences

Protocol 2: Forced Degradation Study

Purpose: Compare degradation pathways with limited batches.

Stress Conditions:

- Thermal: 40°C for 1 month

- Oxidative: 0.01% H₂O₂, 25°C, 24h

- pH: pH 3 and pH 9, 25°C, 1 week

- Mechanical: Vortexing and freeze-thaw cycles

Analysis:

- Monitor formation of degradation products

- Compare degradation profiles using principal component analysis (PCA)

- Assess qualitative and quantitative differences in degradation pathways

Visualizations

Early-Phase Comparability Workflow

Late-Phase Comprehensive Strategy

Comparability Decision Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Comparability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Phase-Appropriate Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard | Benchmark for comparison | All phases - qualification level varies |

| Orthogonal LC Columns | Separation mechanism diversity | Early: 2-3 methods; Late: 4-5 methods |

| MS Calibration Standards | Mass accuracy verification | Critical for peptide mapping and intact mass |

| Forced Degradation Reagents | Stress testing agents | Early: limited stresses; Late: comprehensive |

| Stability Indicating Assay Kits | Rapid stability assessment | Early: screening; Late: validated methods |

| Process-Related Impurity Standards | Specific impurity detection | Late-phase comprehensive assessment |

| Biological Activity Assay Reagents | Functional assessment | Early: binding assays; Late: potency assays |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q: How do we prioritize risks when we only have data from a very limited number of batches for our comparability study?

A: A structured risk assessment is crucial. Begin with a qualitative analysis to quickly identify which process changes pose the highest risk to product quality, safety, and efficacy. For these high-priority risks, you can then apply a semi-quantitative approach to standardize scoring and justify your focus, even with limited data [29]. The initial risk assessment should directly determine the scope and depth of your comparability study [30].

Q: What is the practical difference between qualitative and quantitative risk assessment methods in this context?

A: The choice significantly impacts the defensibility of your decisions with limited batches:

- Qualitative Risk Analysis is scenario-based and uses scales like "High/Medium/Low" for probability and impact. It is quick to implement and ideal for initial, broad screening of risks when data is sparse [31].

- Quantitative Risk Analysis uses objective numerical values and measurable data. It is more rigorous but requires high-quality data, which may not be available with a small number of batches. It is best reserved for high-priority risks where you need to justify investments in controls [31]. A semi-quantitative approach can offer a middle ground [29].

Q: For a major process change like a cell line change, what is the recommended number of batches, and how can we defend using fewer?

A: For a major change, ≥3 batches of commercial-scale post-change product are generally recommended. To justify a smaller number, you must provide a scientifically sound rationale based on a risk assessment. This can include leveraging prior knowledge of process robustness, using a bracketing or matrix approach, or presenting data from a well-justified small-scale model [30].

Q: How do we set meaningful acceptance criteria for comparability studies with limited historical data?

A: Establish prospective acceptance criteria based on all available historical data for the pre-change product. These criteria do not have to be your final quality standards but must be justified. For quantitative methods, the criteria must be a defined range. For qualitative methods, like chromatographic peak shapes, the criteria should be based on a direct comparison to pre-change profiles, demonstrating highly similar patterns and the absence of new variants [30].

Quantitative Risk Analysis Data

Table 1: Key Quantitative Risk Analysis Formulas and Values [31]

| Term | Description | Formula | Application in Comparability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Loss Expectancy (SLE) | Monetary loss expected from a single risk incident. | SLE = Asset Value × Exposure Factor |

Estimates financial impact of a single batch failure due to a process change. |

| Annual Rate of Occurrence (ARO) | Number of times a risk is expected to occur per year. | ARO is estimated from historical data or vendor statistics. | For a new process, this may be based on reliability data for new equipment or systems. |

| Annual Loss Expectancy (ALE) | Expected monetary loss per year due to a risk. | ALE = SLE × ARO |

Used for cost-benefit analysis of implementing a new control or mitigation strategy. |

Table 2: Comparability Study Batch Requirements Based on Risk [30]

| Type of Process Change | Comparability Risk Level | Recommended Number of Post-Change Batches |

|---|---|---|

| Production site transfer | Low | ≥1 batch (Release testing, accelerated stability) |

| Site transfer with minor process changes | Low-Medium | ≥3 batches (Transfer all assays, add functional tests) |

| Changes in culture or purification methods | Medium | 3 batches (May require additional non-clinical PK/PD studies) |

| Cell line changes | Medium-High | ≥3 batches (May require GLP toxicology and human bridging studies) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Primary Structure Analysis via Peptide Mapping

- Objective: To confirm that the amino acid sequence and post-translational modifications are highly similar before and after the process change.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Digest the protein from both pre-change and post-change batches with a specific enzyme (e.g., trypsin).

- Analysis: Separate the resulting peptides using Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Acceptance Criteria: The peptide maps should confirm the primary structure. The profiles must have comparable peak shapes based on retention time and relative intensity. There should be no new or lost peaks in the post-change batch [30].

Protocol: Purity and Impurity Analysis via Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC-HPLC)

- Objective: To quantify and compare the levels of aggregates, monomers, and fragments.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare formulations of the pre-change and post-change products under non-denaturing conditions.

- Analysis: Inject samples onto an SEC-HPLC column to separate species by molecular size.

- Acceptance Criteria: The percentage of the main peak (monomer) should be within statistically derived acceptance criteria. The aggregate, monomer, and fragment peaks should have the same retention times. The profile should show no new species [30].

Risk Assessment and Comparability Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Biologics Comparability Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in Comparability Studies |

|---|---|

| Trypsin (Sequencing Grade) | Enzyme used in peptide mapping to digest the protein for primary structure confirmation by LC-MS [30]. |

| Reference Standard | A well-characterized sample of the pre-change product used as a benchmark for all head-to-head analytical comparisons [30]. |

| Cell-Based Assay Reagents | Includes cells, cytokines, and substrates used in potency assays (e.g., ADCC) to demonstrate functional comparability [30]. |

| SEC-HPLC Molecular Weight Standards | Used to calibrate the Size-Exclusion Chromatography system for accurate analysis of aggregates and fragments [30]. |

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography Buffers | Critical for characterizing charge variants of the protein, which can impact stability and biological activity [30]. |

FAQs on Extended Characterization for Comparability

1. Why is extended characterization critical for comparability studies with limited batches?

Extended characterization provides a deeper, more granular understanding of a molecule's quality attributes than routine release testing [32]. When batch numbers are limited, this orthogonal approach is essential to maximize the information gained from each batch. It helps demonstrate that despite process changes, the molecule's critical quality attributes (CQAs) affecting safety and efficacy remain highly similar, strengthening the scientific evidence for comparability [32] [33].

2. What are the key differences between release testing and extended characterization?

The table below summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | Release Testing | Extended Characterization |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Verify a batch meets pre-defined specifications for lot release [34] | Gain deep molecular understanding for comparability assessments [32] |

| Scope | Focuses on strength, identity, purity, quality (SISPQ) [34] | Orthogonal, in-depth analysis of structure, function, and stability [32] |

| Methods | Validated, routine methods [34] | Platform and molecule-specific methods, including forced degradation studies [34] [32] |

| Frequency | Performed on every batch [34] | Performed at specific development milestones or for comparability [32] |

3. How can we design a phase-appropriate comparability study with few batches?

The strategy should be risk-based and phase-appropriate. In early development, comparability can often be established using single pre- and post-change batches analyzed with platform methods [32]. As development advances toward commercial filing, the standard is a more rigorous, multi-batch comparison (e.g., 3 pre-change vs. 3 post-change) [32]. The key is to focus the testing on CQAs most likely to be impacted by the specific process change [33].

4. What are common CQAs revealed by extended characterization?

Recombinant monoclonal antibodies are complex and heterogeneous. The table below lists key CQAs often investigated during extended characterization [33]:

| Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) | Potential Impact on Product |

|---|---|

| N-terminal Modifications (e.g., pyroglutamate) | Generally low risk; forms charge variants [33] |

| C-terminal Modifications (e.g., lysine truncation) | Generally low risk; forms charge variants [33] |

| Fc-glycosylation (e.g., afucosylation, high mannose) | Can impact effector functions (ADCC) and half-life [33] |

| Charge Variants (e.g., deamidation, isomerization) | Can decrease potency if located in Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs) [33] |

| Oxidation (e.g., of Methionine, Tryptophan) | Can decrease potency and stability; may impact half-life [33] |

| Aggregation | High risk for immunogenicity; loss of efficacy [33] |

5. How do forced degradation studies strengthen a comparability package?

Forced degradation studies "pressure-test" the molecule under stressed conditions (e.g., heat, light, acidic pH) to intentionally degrade it [32]. Comparing the degradation profiles of pre- and post-change batches is a powerful way to show that the molecular integrity and degradation pathways are highly similar, revealing differences not always visible in real-time stability studies [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconclusive Comparability Results with Limited Batches

Problem Description After a process change, analytical data from limited batches (e.g., 1 pre-change vs. 1 post-change) shows minor but statistically significant differences in some quality attributes. It is unclear if these differences impact safety or efficacy, potentially blocking regulatory progression.

Impact Drug development timeline is delayed, and additional non-clinical or clinical studies may be required, increasing costs significantly [33].

Context This often occurs during late-stage development when process changes are scaled up. The risk is higher when the historical data for the attribute is limited and the acceptance criteria are not well-established.

Solution Architecture

Quick Fix (Immediate Action)

- Risk Assessment: Immediately convene a cross-functional team to perform a risk assessment based on the structure-function relationship of the attribute in question [33].

- Method Suitability: Verify the analytical method's performance using a qualified reference standard to ensure data reliability [34].

Standard Resolution (Root Cause Investigation)

- Expand Characterization: Perform extended characterization on the available batches, focusing on the specific attribute and its variants. Use orthogonal methods (e.g., LC-MS for charge variants) to gain a deeper understanding [32].

- Forced Degradation: Subject both batches to forced degradation studies. Similar degradation patterns and rates can provide strong evidence that the molecule's stability and intrinsic properties are comparable, even if initial values differ [32].

- Leverage Platform Knowledge: Use prior knowledge about the molecule class (e.g., common mAb modifications) to justify whether the observed difference is likely to have a clinical impact [34] [33].

Long-Term Strategy (Process Improvement)

- Enhanced Control Strategy: If the difference is confirmed and considered a low risk, justify it to regulators and implement it as part of the updated control strategy for the post-change process.

- Build Historical Data: As more post-change batches are manufactured, incorporate their data to build a new historical data set and refine acceptance criteria.

Issue 2: Failing System Suitability with Platform Methods

Problem Description A platform analytical method, used for years across multiple products, is failing system suitability when testing a new molecule, halting characterization work.

Impact Unable to generate reliable data for comparability assessment. Investigation and method re-development or re-validation can take weeks and cost $50,000-$100,000 [34].

Context Platform methods are designed for molecules with structural similarities but can fail due to unique characteristics of a new molecule or a specific process-related variant.

Solution Architecture

Quick Fix (Restart Testing)

- Use Qualified Reference Standards: Employ a well-characterized, system-suitability standard, such as those from USP, to confirm the instrument and method performance are functioning as intended [34].

- Re-prepare Samples: Re-prepare mobile phases and sample solutions to rule out preparation errors.

Standard Resolution (Identify Cause)

- Troubleshoot the Method: Isolate the cause of failure. Check for column degradation, instrument performance, and buffer pH. Minor adjustments to the method (e.g., gradient, pH) may be sufficient.

- Analyze the Molecule: Investigate if a unique attribute of the molecule (e.g., a specific charge variant or aggregation profile) is interfering with the method. This may require data from other characterization techniques.

Long-Term Strategy (Ensure Robustness)

- Method Optimization or Adaptation: If the platform method is not suitable, optimize it for the new molecule. Using a compendial method (e.g., from USP-NF) as a starting point can save time and cost compared to full in-house development [34].

- Document the Justification: Thoroughly document the investigation and any method modifications, providing a scientific rationale for the changes to ensure regulatory compliance.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Forced Degradation Study for Comparability

Objective: To compare the degradation profiles of pre- and post-change monoclonal antibody batches under stressed conditions to demonstrate similarity in stability behavior [32].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- mAb Samples: Pre-change and post-change drug substance.

- Buffers: Various pH buffers (e.g., pH 3, 5, 9).

- Oxidizing Agent: 0.1% hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂).

- Control Buffer: Histidine or phosphate buffer at formulation pH.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dialyze all mAb samples into a common, appropriate control buffer.

- Concentrate to the desired protein concentration (e.g., 1-10 mg/mL).

- Stress Conditions:

- Thermal Stress: Incubate samples at 40°C for 1-4 weeks.

- Agitation Stress: Agitate samples on an orbital shaker for 24-72 hours.

- Light Stress: Expose samples to UV and visible light per ICH Q1B guidelines.

- Oxidative Stress: Incubate samples with 0.1% H₂O₂ for 2-4 hours at 25°C.

- Acidic/Basic Stress: Adjust samples to low (e.g., pH 3) or high (e.g., pH 9) conditions and incubate for a short duration (e.g., 1 hour).

- Analysis:

- Stop the stress reactions (e.g., by neutralizing pH, adding catalase to quench H₂O₂).

- Analyze all stressed samples and unstressed controls side-by-side using a panel of methods:

- SEC-HPLC: For aggregates and fragments.

- CE-SDS / SDS-PAGE: For fragments and size variants.

- IEC-HPLC / cIEF: For charge variants.

- Peptide Map with LC-MS: For specific PTM identification (e.g., oxidation, deamidation).

Protocol 2: Extended Characterization for mAb Comparability

Objective: To perform an in-depth, orthogonal analysis of the primary, secondary, and higher-order structure of mAbs to establish analytical comparability [32] [33].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- mAb Samples: Pre-change and post-change drug substance.

- Digestion Enzymes: Trypsin, Lys-C.

- Reducing & Alkylating Agents: Dithiothreitol (DTT), Iodoacetamide.

- LC-MS Grade Solvents: Water, acetonitrile, formic acid.

Methodology:

- Primary Structure Analysis:

- Intact Mass Analysis: Use LC-ESI-TOF MS under reduced and non-reduced conditions to confirm molecular weight and detect major mass variants.

- Peptide Mapping: Denature, reduce, alkylate, and digest the mAb with trypsin. Analyze the peptides using RP-UPLC coupled with MS. Identify and quantify post-translational modifications (PTMs) like deamidation, isomerization, and oxidation.

- Higher-Order Structure (HOS) Analysis:

- Circular Dichroism (CD): Perform far-UV and near-UV CD to assess secondary and tertiary structure.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Measure thermal stability and determine melting temperatures (Tm) of different domains.

- Purity and Impurity Analysis:

- Size Variants: Use SEC-MALS to quantify aggregates and fragments and determine absolute molecular weight.

- Charge Variants: Use cation-exchange chromatography (CEX-HPLC) or capillary isoelectric focusing (cIEF) to profile acidic and basic species.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials used in extended characterization studies for mAbs.

| Research Reagent | Function in Characterization |

|---|---|

| USP Reference Standards | Well-characterized standards for system suitability and method qualification; ensure accuracy and regulatory compliance [34]. |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Chemically defined raw materials used during production; their quality can directly impact product CQAs like glycosylation [33]. |

| Chromatography Resins | Used in purification (e.g., Protein A). Changes in resin lots can impact impurity clearance and must be evaluated for comparability [33]. |

| Enzymes (Trypsin, Lys-C) | Proteases used for peptide mapping to analyze amino acid sequence and identify post-translational modifications [32] [33]. |

| Stable Cell Line | The foundational source of the recombinant mAb; critical for ensuring consistent product quality and a primary focus of comparability studies [33]. |

Leveraging Split-Manufacturing and Historical Data When Concurrent Batches Are Limited

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Considerations & References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Design & Power | Insufficient power to detect meaningful differences; high variability masks effects. | Limited batch numbers, high inherent batch-to-batch variability, suboptimal allocation of resources in split-plot design [35]. | Use I-optimal designs to minimize prediction variance; leverage historical data to inform model priors and reduce required new batches [35]. | In split-plot designs, ensure at least one more whole plot than the number of hard-to-change factor levels to accurately estimate variance [36]. |

| Failed Comparability | Analytical results show significant differences between pre- and post-change batches. | The manufacturing change genuinely impacted a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA); analytical methods are not sufficiently sensitive or specific [37] [30]. | Conduct a risk assessment to focus on CQAs; use head-to-head testing with cryopreserved samples; employ extended characterization assays [30]. | Comparability does not require identical attributes, but highly similar ones with no adverse impact on safety/efficacy [37]. |

| Data Integration & Analysis | Inability to integrate or analyze diverse data sources (historical, process, analytical). | Data silos, inconsistent formats, lack of a unified data management platform [38]. | Implement data integration approaches (e.g., ELT/ETL) to create a single source of truth; use statistical models that account for split-plot error structure [38] [36]. | For split-plot ANOVA, use different error terms for whole-plot and subplot effects to avoid biased results [36]. |

| Handling Missing Data | Failed experimental runs (e.g., no product formed). | Process robustness issues; specific combinations of covariates and mixture variables are non-viable [35]. | Document all failures; use experimental designs that are robust to a certain percentage of missing data; analyze failure patterns to understand root causes [35]. | In the potato crisps case study, 47 of 256 runs failed, and analyzing the conditions for failure provided valuable insight [35]. |

| Regulatory Scrutiny | Regulatory questions on the adequacy of the limited-batch comparability study. | The justification for the number of batches and the statistical approach was not sufficiently detailed [37] [30]. | Base batch number justification on risk and phase of development; use all available data (including process development); pre-define acceptance criteria based on historical data [37] [30]. | For a major change, ≥3 post-change batches are typical. For minor changes, ≥1 batch may suffice with sound justification [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)