PCR vs. Culture for Mycoplasma Testing: A Strategic Guide for Biopharmaceutical Quality Control

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting between PCR and culture-based methods for mycoplasma testing.

PCR vs. Culture for Mycoplasma Testing: A Strategic Guide for Biopharmaceutical Quality Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting between PCR and culture-based methods for mycoplasma testing. It covers the foundational principles of mycoplasma contamination and its risks, delves into the methodological workflows of PCR and culture techniques, and offers troubleshooting strategies for optimization. A detailed validation framework is presented to guide method selection and compliance with global pharmacopeia standards, empowering scientists to implement robust, efficient testing protocols that ensure product safety and accelerate biopharmaceutical development.

Mycoplasma Contamination: Understanding the Invisible Threat to Cell Cultures and Biologics

Mycoplasma species represent a significant and unique challenge in biomedical research and biopharmaceutical production. As the smallest known free-living organisms, their size and absence of a rigid cell wall make them a pervasive threat to cell cultures, with contamination rates estimated between 15% and 35% for continuous cultures [1] [2]. This contamination can lead to costly batch failures, product recalls, and poses potential risks to patient safety [1]. Furthermore, in clinical settings, Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common cause of pediatric community-acquired pneumonia, and the global rise of macrolide-resistant strains is complicating treatment strategies [3] [4] [5]. This guide objectively compares the performance of PCR-based and culture-based methods for detecting these elusive contaminants, providing critical data to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals safeguard their work.

Unpacking the Threat: Mycoplasma's Distinctive Biology

The unique risk profile of Mycoplasma is a direct consequence of its fundamental biology, which differentiates it from typical bacterial contaminants.

Size and Filterability: Mycoplasmas are remarkably small, with diameters ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 µm [2]. This diminutive size, coupled with their metabolic activity, allows them to passively penetrate the 0.2 µm filters commonly used to sterilize cell culture media and biopharmaceutical products, providing a direct route for contamination [2].

Lack of a Cell Wall: Unlike most bacteria, Mycoplasmas lack a rigid cell wall. This makes them naturally resistant to a broad class of common antibiotics, including beta-lactams (e.g., penicillin), which target cell wall synthesis [2] [5]. This trait necessitates the use of different classes of antibiotics for treatment, such as macrolides, which target protein synthesis [5].

Stealth and Impact: Their small size and plastic morphology make them difficult to detect by conventional optical microscopy. They do not cause the visible turbidity in culture media typical of other bacterial contaminants. However, they can profoundly alter the function and metabolism of infected cell cultures, compromising research data and the safety of biologically derived products [1] [2].

Comparative Methodologies: PCR vs. Culture for Mycoplasma Testing

The two primary methods for Mycoplasma detection are culture-based techniques, the historical gold standard, and PCR-based molecular tests. The experimental protocols and key differentiators are outlined below.

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Protocol 1: Culture-Based Method The culture-based method relies on cultivating the organism in specialized media. A typical protocol, as used in clinical isolate studies, involves the following steps [3]:

- Sample Inoculation: Clinical specimens (e.g., throat swabs) are immediately inoculated into a nutrient-rich PPLO broth, supplemented with horse serum, yeast extract, and antibiotics to inhibit competing flora.

- Incubation and Monitoring: Cultures are incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 2–3 weeks. Due to slow growth and lack of turbidity, cultures are monitored for a color change (red to yellow) of a phenol red pH indicator, signifying acid production from glucose metabolism.

- Subculture and Identification: Positive broths are subcultured onto solid PPLO agar and incubated for an additional 1–2 weeks. Colonies are examined microscopically for the characteristic "fried-egg" appearance.

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST): Using a multiple dilution method, isolates are tested against a panel of antibiotics (e.g., macrolides, tetracyclines, quinolones) to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and assess resistance profiles [3].

Protocol 2: PCR-Based Method (PCR-MALDI-TOF MS) Advanced molecular techniques combine PCR with mass spectrometry for high-throughput genotyping. A detailed protocol is described as follows [3]:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: DNA is extracted from purified isolates, quantified (e.g., to 12–83 ng/μL using Qubit 3.0), and diluted in nucleic acid-free water as a negative control.

- Multiplex PCR Amplification: A 5 µL reaction volume is prepared containing DNA template, PCR buffer, and a primer mixture. Amplification conditions include initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15 s), annealing (59°C for 30 s), and extension (72°C for 30 s).

- Post-PCR Treatment: PCR products are treated with Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (SAP) to remove free dNTPs.

- Mass Probe Extension (MPE): An MPE mixture containing primers, enzymes, and termination nucleotides (E-ddNTPs) is added to the SAP-treated products. Thermocycling is performed to conduct a single base pair extension.

- Salt Purification and Analysis: The products are purified with resin and ultrapure water. The supernatant is mixed with a chemical matrix (3-HPA) and crystallized for analysis.

- SNP Identification: The purified samples are tested using a MALDI-TOF MS system (e.g., QuanTOF I). The resulting mass spectra are analyzed to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with antibiotic resistance, such as mutations in the 23S rRNA gene [3].

Side-by-Side Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes the critical differences in performance between the two methods, drawing from direct experimental data and market analyses.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Mycoplasma Testing Methods

| Feature | PCR-Based Method | Culture-Based Method |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Detection of microbial DNA via amplification | Microbial growth in specialized media |

| Turnaround Time | ~4.8 hours to result [6]; same-day possible [7] | 24-48 hours for AST; 2-3 weeks for full culture [3] |

| Sensitivity | High; detects DNA from non-viable and viable cells | Lower; dependent on viable, cultivable organisms |

| Key Advantage | Speed, high-throughput, identifies resistance mutations | Phenotypic resistance profile, historical gold standard |

| Key Limitation | Genotype-phenotype discordance possible [3] | Lengthy process, cannot detect non-viable organisms |

| Cost (USD) | ~$300 - $1,200 per kit [8] | ~$100 per kit [8] |

Critical Experimental Data and Emerging Resistance Profiles

Empirical data from recent studies highlights the practical implications of method choice and underscores the growing challenge of antibiotic resistance.

Diagnostic and Clinical Outcomes Data

Recent comparative studies across different clinical fields demonstrate a consistent trend of PCR-based methods outperforming traditional culture.

Table 2: Performance Data of PCR vs. Culture from Clinical Studies

| Study Focus | PCR Sensitivity | PCR Specificity | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Infections | 98.3% (vs. culture) [7] | 73.5% (vs. culture) [7] | PCR detected 110 significant pathogens missed by culture [7]. |

| Complicated UTI | N/A | N/A | PCR-guided treatment provided significantly better clinical outcomes (88.1% vs 78.1% success) [9]. |

| Bloodstream Infections | N/A | N/A | dPCR detected 63 pathogenic strains across 42 positive samples, compared to 6 strains via blood culture [6]. |

The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis in Mycoplasma pneumoniae

The utility of culture-based AST is evident in tracking the alarming rise of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP), a major clinical concern, particularly in pediatrics.

Resistance Mechanisms: Resistance is primarily linked to point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, most commonly at positions A2063G, A2064G, and A2617C [3] [4]. These mutations reduce macrolide binding affinity, rendering first-line therapies like azithromycin ineffective [3].

Global Prevalence: Resistance rates vary significantly by region. A 2023-2024 Russian study found the A2063G mutation in ~40% of clinical samples [4]. In contrast, a 2023 study in Xi'an, China, reported that 100% of cultured isolates harbored A2063G, A2064T, and A2617C mutations, with a phenotypic resistance rate of 38.6% for macrolides [3]. Japanese data from November 2024 indicates that 20-30% of infections are antibiotic-resistant [8].

Genotype-Phenotype Discordance: The Xi'an study revealed a critical finding: while resistance mutations were universally present genotypically, phenotypic resistance was observed in only 38.6% of isolates [3]. This discordance underscores the importance of integrating both molecular and culture-based susceptibility testing to guide effective clinical management and avoid unnecessary use of second-line antibiotics [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents and kits is fundamental for effective Mycoplasma testing. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mycoplasma Testing

| Product / Solution | Function / Application | Specific Example (if cited) |

|---|---|---|

| PPLO Broth & Agar | Nutrient-rich culture media for cultivating fastidious Mycoplasma species. | Used in clinical isolate culture protocols [3]. |

| PCR & Multiplex Kits | Amplify specific Mycoplasma DNA sequences for highly sensitive detection. | Mycoplasma pneumoniae/Chlamydophila pneumoniae-FRT kit [4]. |

| Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Plates | Pre-configured panels to determine Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC). | M. pneumoniae culture and susceptibility test kit (Autobio Diagnostics) [3]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Purify DNA from samples for downstream molecular analysis. | MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit [4]. |

| MALDI-TOF MS System | High-throughput platform for rapid microbial identification and genotyping. | QuanTOF I system (Intelligene Biosystems) [3]. |

| Lateral Flow Test Kits | Rapid, convenient immunochromatographic tests for preliminary screening. | SwiftDx Mycoplasma Detection Kit [1]. |

| Pruvonertinib | Pruvonertinib, CAS:2064269-82-3, MF:C27H32N8O2, MW:500.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AD 0261 | AD 0261, MF:C27H31F2N3O, MW:451.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

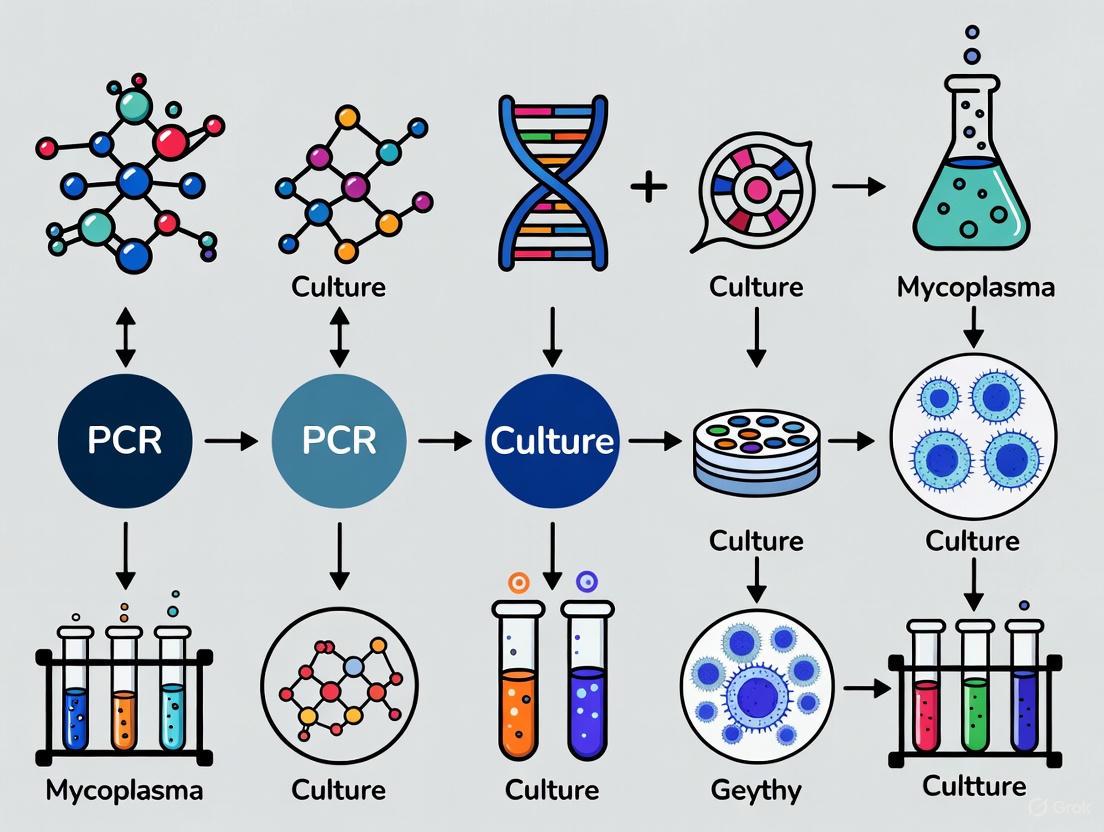

Visualizing the Testing Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the logical flow and key decision points for the two primary testing methodologies.

Culture-Based Testing Workflow

PCR-Based Testing Workflow

The unique biological characteristics of Mycoplasma—its minimal size, filterability, and intrinsic resistance to common antibiotics—demand vigilant and effective testing strategies. The data clearly demonstrates that PCR-based and culture-based methods are not mutually exclusive but are, in fact, complementary. PCR offers unparalleled speed, sensitivity, and the ability to screen for resistance genotypes, making it ideal for rapid quality control and initial diagnosis. Culture remains indispensable for obtaining phenotypic antibiotic susceptibility profiles and investigating cases where genotypic predictions do not match phenotypic expression [3]. For researchers and drug developers, a layered approach is optimal: employing rapid, high-throughput PCR for routine screening and follow-up with culture-based AST when resistance is suspected or confirmation is required. This integrated strategy, leveraging the strengths of both technologies, is the most robust defense against the unique and persistent threat posed by Mycoplasma contamination and infection.

Mycoplasma contamination represents one of the most significant yet frequently overlooked threats in cell culture laboratories worldwide. With the potential to alter cellular metabolism, compromise research validity, and jeopardize biopharmaceutical product safety, these minute contaminants demand sophisticated detection strategies. The scientific community increasingly recognizes that traditional culture-based methods, long considered the gold standard, may no longer suffice for modern applications requiring rapid results and extreme sensitivity. This comprehensive analysis examines the profound impacts of mycoplasma contamination and objectively compares the performance of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) versus culture methodologies within the framework of mycoplasma testing research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based guidance for safeguarding their work.

The Hidden Threat: How Mycoplasma Contamination Compromises Cellular Systems

Understanding the Contaminant

Mycoplasmas are the smallest self-replicating organisms known to science, measuring just 0.2-0.3 microns in diameter [10]. Their minute size and lack of a cell wall make them resistant to common antibiotics like penicillin and streptomycin and allow them to pass through standard sterilization filters of 0.45-0.22 µm porosity [11] [12]. These bacteria can grow to extremely high concentrations (10â·-10⸠organisms/mL) in cell cultures while remaining invisible under conventional light microscopy [10]. Of the more than 200 known Mollicutes species, approximately 20 have been isolated from infected cell cultures, with eight species—M. arginini, M. fermentans, M. orale, M. hyorhinis, M. hominis, M. salivarium, M. pirum, and Acholeplasma laidlawii—responsible for over 95% of contamination incidents [11].

Metabolic Consequences of Contamination

Mycoplasmas possess limited biosynthetic capabilities and consequently depend entirely on their host cells for essential nutrients. This parasitic relationship leads to significant metabolic alterations in contaminated cells:

Nutrient Depletion: Mycoplasmas compete with host cells for fundamental nutrients including amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, nucleic acid precursors, and choline [12]. This competition can deplete culture media of components essential for host cell viability and function.

Arginine and Purine Metabolism Disruption: Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC/MS)-based metabolomics studies reveal that mycoplasma contamination induces significant perturbations in arginine and purine metabolic pathways [13]. Research using human pancreatic carcinoma cells (PANC-1) demonstrated that 23 identified metabolites showed significant alterations following mycoplasma infection.

Energy System Alteration: The metabolic changes extend to cellular energy supply systems, potentially explaining the observed effects on various cell functions when mycoplasma is present [13]. Since cell metabolism is involved in virtually every aspect of cellular function, these disruptions can have far-reaching consequences for research outcomes.

Impacts on Research Validity and Product Safety

The effects of mycoplasma contamination extend beyond metabolic changes to fundamentally compromise scientific research and product quality:

Cellular Function Modifications: Contaminated cells can exhibit up to 15-fold increased resistance to chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin, vincristine, and etoposide in tetrazolium-based MTT assays [13]. Mycoplasma contamination has also been shown to stimulate prostaglandin E2 production and interfere with amyloid-beta peptide degradation.

Genetic and Molecular Changes: Mycoplasmas can disrupt nucleic acid synthesis, cause chromosomal aberrations, alter cell membrane antigenicity, and change cellular responses to transfection and viral infection [10]. These changes potentially invalidate experimental results across multiple research domains.

Biopharmaceutical Risks: In manufacturing environments, mycoplasma presence can decrease bioreactor yields, interfere with in vitro tests, and potentially cause patient disease [14]. For cell-based therapies and advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), these contaminants present significant patient safety concerns.

Methodological Comparison: PCR Versus Culture-Based Detection

Detection Sensitivity and Specificity

Robust comparative studies demonstrate significant performance differences between detection methodologies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | Positive Predictive Value (%) | Negative Predictive Value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Conventional PCR | 94.44 | 100 | 96.77 | 100 | 92.85 |

| Enzymatic MycoAlert | 53.33 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| DNA DAPI Staining | 46.66 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Microbial Culture | 33.33 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

Data adapted from a comparative study evaluating 30 cell lines using five different detection techniques [11].

The superior performance of PCR-based methods, particularly real-time PCR, is further evidenced by dilution experiments demonstrating correct detection of infecting mycoplasmas at levels as low as 1/10â´, significantly surpassing the sensitivity of alternative assays [15].

Turnaround Time and Operational Considerations

The operational characteristics of detection methods present substantial practical implications for research and quality control environments:

Table 2: Operational Characteristics of Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Parameter | Microbial Culture | Conventional PCR | Real-time PCR | New Automated NAT Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Turnaround Time | 4-28 days [14] | 1-2 days | Several hours | ~1 hour [14] |

| Hands-on Time | Moderate to high | Significant | Moderate | Minimal [14] |

| Operator Skill Requirements | High | High | High | Minimal training needed [14] |

| Suitability for Short Shelf-life Products | Limited | Moderate | Good | Excellent [14] |

The lengthy turnaround time associated with culture methods (up to 28 days) creates significant bottlenecks in biopharmaceutical manufacturing, particularly for products with short shelf lives [14]. In contrast, modern nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAT), including fully automated systems like the BIOFIRE Mycoplasma Test, can deliver results in approximately one hour with minimal hands-on time [14].

Regulatory Recognition and Method Validation

Global regulatory frameworks have evolved to recognize the value of NAT methods:

The revised European Pharmacopoeia chapter 2.6.7 "Mycoplasmas" (version 12.2) establishes NAT as equivalent to culture-based methods, harmonizing requirements with the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP 18 G3) and United States Pharmacopoeia (USP <63> and USP <77> draft) [16].

Defined sensitivity requirements for NAT methods specify a limit of detection of ≤10 CFU/mL or <100 genomic copies/mL, with genomic copies enhancing comparability between NAT and culture results [16].

Method validation must be performed in the user's own product matrix, even when using validated commercial kits, to ensure absence of inhibitory substances and confirm assay sensitivity under real conditions [16].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Real-Time PCR Detection Methodology

The superior performance of real-time PCR for mycoplasma detection is demonstrated through specific experimental protocols:

Sample Preparation: Cell lines are cultured in antibiotics-free medium for at least 4-7 days without medium exchange to allow mycoplasma proliferation [11]. Both cells and supernatant must be tested as mycoplasmas can adhere to or reside within cells [16].

DNA Extraction: Nucleic acids are extracted from both positive and negative control cell lines. Five mycoplasma-contaminated cell lines are typically designated as positive controls and five mycoplasma-free cell lines as negative controls [11].

Amplification and Detection: Real-time PCR is conducted using commercial diagnostic kits with genus-specific primers targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA gene [11]. The PCR Mycoplasma Test Kit I/RT from PromoKine has been used in comparative studies.

Quality Control: The system must include an internal control to rule out inhibition and an external positive control with defined genomic copies or CFU content close to the limit of detection, plus a negative control [16].

Protocol 2: Metabolic Impact Assessment via LC/MS-Based Metabolomics

The metabolic consequences of mycoplasma contamination can be quantified using sophisticated analytical approaches:

Sample Collection: Cells are grown to approximately 90% confluence, quenched with liquid nitrogen, and harvested by scraping. Metabolites are extracted using chilled methanol followed by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 15 minutes at 4°C [13].

Chromatographic Separation: Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) is performed using an Atlantis Silica HILIC column with a binary mobile phase system and linear gradient over 30 minutes [13].

Mass Spectrometric Analysis: A Q Exactive benchtop Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with heated ESI source operates in both positive and negative modes at 70,000 FWHM resolution for full scan mode (80-900 m/z) followed by data-dependent MS/MS at 17,500 FWHM resolution [13].

Data Processing: Multivariate principal component analysis (PCA) and univariate analysis are performed using specialized bioinformatics software. Metabolites of interest are filtered based on significant fold changes (fold change >2 or <-2) and statistical significance (p<0.05) [13].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing robust mycoplasma detection requires specific quality-controlled reagents and reference materials:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mycoplasma Detection

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative DNA Reference Materials | Analytical sensitivity evaluation | ATCC provides titered reference strains with low GC/CFU ratio under ISO 17034 accreditation [17] |

| Venor Mycoplasma qPCR Assay | Regulatory-compliant detection | Fully aligned with EP 2.6.7, detects >130 mollicute species via reverse transcriptase qPCR [16] |

| 100GC Mycoplasma Standards | Quantitative reference | Traceable 100 genomic copies/vial for sensitivity verification in product-specific matrices [16] |

| Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Multiple species detection | ATCC kit detects over 60 species of Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, Spiroplasma, and Ureaplasma [17] |

| MycoAlert Assay Kit | Enzymatic detection | Detects ATP generation as indicator of mycoplasma activity; shows 53.33% sensitivity in comparative studies [11] |

| BIOFIRE Mycoplasma Test | Automated NAT system | Closed "lab in a pouch" system with minimal hands-on time, results in ~1 hour [14] |

The high stakes of mycoplasma contamination demand rigorous detection strategies that balance sensitivity, specificity, speed, and regulatory compliance. The evidence clearly demonstrates that PCR-based methods, particularly real-time PCR, outperform traditional culture-based approaches in detecting these insidious contaminants. As the field advances, fully automated NAT systems promise to further reduce detection times while maintaining the sensitivity required for protecting research integrity and biopharmaceutical products. Researchers and manufacturers must prioritize routine mycoplasma testing using the most appropriate detection methodology for their specific application, ensuring the validity of scientific discoveries and the safety of biological products.

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP), European Pharmacopoeia (EP), and Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP) establish the legally binding quality standards for biological products in their respective regions. These pharmacopeias provide comprehensive frameworks for testing biologics to ensure their identity, purity, potency, and safety before patient release. Harmonization efforts by the Pharmacopoeial Discussion Group (PDG), formed in 1990, have created greater alignment between these standards, though critical differences remain that global manufacturers must navigate [18]. For biologics, which include vaccines, cell and gene therapies, and therapeutic proteins, adherence to these compendial requirements is not merely advisory but a regulatory imperative for market authorization and lot release.

This guide focuses specifically on the application of USP, EP, and JP standards to biologics, with a detailed examination of mycoplasma testing—a critical safety requirement where the choice between traditional culture methods and modern PCR-based assays presents significant practical and regulatory considerations.

Comparative Analysis of USP, EP, and JP Frameworks

The three pharmacopeias share the common goal of ensuring drug quality and patient safety but reflect their regions' distinct regulatory histories and medical traditions. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of the Major Pharmacopoeias

| Feature | USP (United States) | EP (European) | JP (Japanese) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governing Body | United States Pharmacopeial Convention [19] | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM) [19] | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) [19] |

| Legal Status | Enforceable by the FDA [19] | Legally binding in member states [19] | Forms the legal basis for all pharmaceuticals in Japan [19] |

| Update Cycle | Ongoing revisions [19] | New edition every 3 years [19] | New edition every 5 years, with supplements [19] |

| Unique Focus | Broad scope, including drugs, supplements, and food ingredients [19] | Strong emphasis on packaging standards and herbal products [19] | Integration of modern pharmaceuticals with traditional Kampo medicines [19] |

| Testing Specialties | Leader in biotech and biologics testing methods [19] | Extensive protocols for herbal products [19] | Advanced techniques like quantitative NMR [19] |

The JP uniquely balances modern pharmaceutical science with traditional Kampo medicine, while the EP places significant emphasis on packaging standards [19]. The USP's scope is notably broad, extending into dietary supplements and food ingredients, and its standards are recognized in over 140 countries, giving it a wide international influence [19]. A key difference for manufacturers is the update cycle: the EP's formal three-year cycle and the JP's five-year cycle offer more predictable revision schedules compared to the USP's ongoing revision process, which can present a dynamic compliance landscape [19].

Harmonization and Key Differences in Testing Requirements

The Drive for Harmonization

The Pharmacopoeial Discussion Group (PDG) works to harmonize excipient monographs and general chapters to ease the global trade of medicines [18]. This collaboration is crucial for reducing redundant testing for companies operating internationally. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) further supports this through its Q4B Expert Working Group, which evaluates and recommends specific pharmacopoeial texts for use across the ICH regions [18]. For example, the ICH has declared that the sterility test chapters of the USP (<61>, <71>), EP (2.6.1, 2.6.12), and JP (4.05, 4.06) can be used interchangeably, subject to certain conditions [18].

Specific Testing Mandates for Biologics

Biologics require a multi-faceted testing strategy to guard against various impurities and contaminants. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive testing workflow integrated throughout the bioproduction process.

Key testing categories include:

- Sterility Testing: Governed by USP <61>, <62>, and <71>; EP 2.6.1, 2.6.12, and 2.6.13; and JP 4.05 and 4.06. These tests detect the presence of viable microorganisms and are required for final product release. The ICH Q4B has deemed these chapters interchangeable [18].

- Endotoxin Testing: Primarily using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay, this test is covered under USP <85>, EP 2.6.14, and JP 4.01. These chapters are also considered interchangeable, as their reference standards are calibrated against the WHO international standard [18].

- Subvisible Particulate Testing: For injectables like biologics, USP <788> (which is harmonized with EP 2.9.19 and JP 6.07) sets limits on particulate matter. Therapeutic protein injections have a tailored chapter, USP <787> [20].

- Mycoplasma Testing: This is a critical and complex release requirement for products derived from cell cultures, detailed in the following section.

Mycoplasma Testing: A Critical Release Requirement

The Contamination Risk

Mycoplasmas are the smallest free-living organisms and are a major concern in biopharmaceutical manufacturing. They are notorious contaminants of cell cultures, with estimates suggesting they affect 15–35% of all continuous cell cultures globally [2]. Unlike many bacteria, mycoplasmas lack a rigid cell wall, making them resistant to many antibiotics and allowing them to pass through standard sterilizing filters. Critically, contamination often causes no visible changes to the cell culture, such as turbidity or pH shifts, meaning specialized testing is the only reliable detection method [18] [21].

Compendial Testing Methods: Culture vs. PCR

The pharmacopeias specify two primary methodological approaches for mycoplasma testing, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Mycoplasma Testing Methods per USP, EP, and JP

| Aspect | Culture-Based Method | PCR-Based Method |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Growth in broth/agar media and indicator cell lines [21] | Nucleic acid amplification of Mycoplasma DNA [18] |

| Turnaround Time | 28 days [22] [21] | As little as a few hours [18] |

| Sensitivity | High for cultivable species | High and broad for species with known sequences |

| Key Regulatory Chapters | USP <63>, EP 2.6.7, JP 9 [21] | EP 2.6.7 (includes NAT), general guidance in USP <1223> [18] |

| Primary Use | Lot release testing (where required) | In-process testing, raw material release, rapid lot release |

The culture method is the historical gold standard for final product release. It involves inoculating the sample into both broth and agar media and incubating for 28 days, with regular subculturing to enrich for any present mycoplasmas. The method is validated for its ability to detect a panel of representative species, such as M. pneumoniae, M. orale, and A. laidlawii [18] [21]. While highly sensitive, the 28-day duration often makes it the rate-limiting step for product release [22].

PCR-based methods, or Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques (NAATs), offer a rapid alternative. These tests can provide results in hours, enabling faster decision-making during manufacturing [18]. While traditionally used for in-process testing, their acceptance for final lot release is growing, supported by technological advances and their inclusion in pharmacopeial chapters like EP 2.6.7.

Experimental Comparison: Culture vs. PCR for Mycoplasma Detection

Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

A standard protocol to validate a PCR method against the compendial culture method involves the following steps:

- Sample Preparation: Spike a representative biologic product (e.g., a monoclonal antibody solution) with low levels (10-100 CFU/mL) of compendial mycoplasma strains (e.g., M. pneumoniae and A. laidlawii) [18] [21]. Include unspiked samples as negative controls.

- Culture Method Arm:

- Inoculate the sample into both liquid broth and agar media as specified in USP <63>, EP 2.6.7, and JP 9.

- Incubate at 36±1°C under both aerobic and microaerophilic conditions.

- Subculture from the broth to fresh media on days 3, 7, 14, and 21 post-inoculation.

- Observe agar plates for characteristic "fried-egg" colonies and check broth for turbidity over a 28-day period [21].

- PCR-Based Arm:

- Extract nucleic acids from an aliquot of the same spiked and unspiked samples.

- Perform PCR using primers targeting a conserved region of the mycoplasma 16S rRNA gene.

- Include appropriate positive controls (mycoplasma genomic DNA) and negative controls (no-template).

- Run the assay and analyze results, which can be completed within one working day.

- Data Analysis: Compare the detection sensitivity, specificity, and rate of contamination detection between the two methods.

Data and Outcomes

This experimental approach consistently reveals the trade-offs between the two methods. A recent clinical study in another diagnostic context demonstrated that PCR panels reduced the turnaround time from ~48 hours to ~12 hours—a four-fold improvement—while also increasing the diagnostic yield by over 19 percentage points [23]. While this data is from a clinical setting, it underscores the profound efficiency gains of PCR.

In the context of biologics testing, the data can be summarized as follows:

Table 3: Experimental Data from Comparative Method Testing

| Performance Metric | Culture-Based Method | PCR-Based Method |

|---|---|---|

| Turnaround Time | 28 days [22] [21] | 1-2 days [18] |

| Ability to Detect Non-Cultivable Species | Limited to cultivable strains | High (with appropriate primer design) |

| Risk of Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) Miss | High (cannot detect VBNC organisms) | Low (detects DNA regardless of cultivability) |

| Susceptibility to Sample Inhibition | Low | Moderate (requires careful validation to rule out inhibitors) |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative (CFU) | Quantitative (with qPCR standard curve) |

The experimental outcomes clearly show that PCR offers superior speed and broader detection capability, while the culture method remains a robust, growth-based standard. The regulatory trend is moving toward greater acceptance of rapid methods, particularly for products with short shelf-lives like cell and gene therapies, where a 28-day wait is impractical [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successfully implementing compendial testing requires the use of qualified reagents and reference materials.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Compliance Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application in Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma Positive Control Strains (e.g., M. pneumoniae, M. orale) [18] | Acts as a positive control to demonstrate the test can support growth or detect target DNA. | Used in both culture and PCR methods for assay validation and as a run control. |

| Control Standard Endotoxins (CSE) [18] | A standardized endotoxin preparation traceable to an international standard. | Used to generate standard curves and positive controls in LAL tests for endotoxin detection. |

| Validated PCR Kits & Reagents | Provides optimized primers, probes, and master mixes for specific detection of mycoplasma DNA. | Used in NAAT for mycoplasma testing; must be validated for sensitivity and specificity. |

| Qualified Culture Media (Broth & Agar) | Supports the growth of a wide range of mycoplasma species. | Used in the compendial 28-day culture method for mycoplasma detection. |

| International Reference Standards | The highest-order standard for a given analyte (e.g., endotoxin, a specific protein). | Used to qualify in-house secondary standards and ensure global assay comparability. |

| GLX351322 | GLX351322, MF:C21H25N3O5S, MW:431.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MEK-IN-4 | MEK-IN-4, MF:C21H18N4OS, MW:374.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Navigating the regulatory imperatives of USP, EP, and JP is fundamental to the successful development and commercialization of biological products. While harmonization efforts have created significant alignment, understanding the nuanced differences in testing requirements, particularly for critical areas like mycoplasma detection, is essential. The data and comparisons presented demonstrate a clear industry trend: the future of biologics release testing lies in the strategic integration of rapid, sensitive methods like PCR with the established robustness of traditional culture-based assays. This hybrid approach balances the need for speed and efficiency with the unwavering commitment to patient safety mandated by global regulatory authorities.

In the biopharmaceutical industry, ensuring the sterility of cell banks and production processes is not merely a quality control step but a fundamental prerequisite for patient safety and product efficacy. Mycoplasma contamination constitutes one of the most prevalent and serious threats, affecting an estimated 15-35% of continuous cell cultures globally, with some selected populations reporting rates as high as 65-80% [24] [25] [26]. These bacteria, devoid of a cell wall, can profoundly alter cell physiology and metabolism, leading to erroneous research data, compromised product quality, and significant economic losses [27] [25]. The following comparison guide provides an objective analysis of the primary methods used to detect mycoplasma, framing this critical quality control issue within the broader thesis of PCR versus traditional culture methods.

Understanding the scope and origin of contamination is the first step in its control. The rates of mycoplasma infection are persistently high within biopharmaceutical manufacturing, posing both safety and economic risks [24] [26].

The introduction of mycoplasma into a production process can be traced to several key sources:

- Laboratory Personnel: Operations staff are a major source of human-origin mycoplasma species. Improper techniques, such as mouth pipetting, can introduce organisms from the oropharyngeal tract [11] [25].

- Contaminated Biologicals: While less common today due to improved vendor qualification, raw materials of animal origin, particularly fetal bovine serum (FBS) and trypsin, historically were significant sources of bovine and swine mycoplasma species [25] [26].

- Cross-Contamination in the Lab: A single infected cell culture can rapidly spread mycoplasma to other cultures in the same laboratory. Live mycoplasma can be recovered from laminar flow hood surfaces days after working with a contaminated culture, leading to the infection of clean cultures subcultured in the same hood [25].

Distribution of Mycoplasma Species

While over 190 species of mycoplasma exist, only a handful account for the vast majority of cell culture contaminations. The table below summarizes the most common species and their origins.

Table 1: Common Mycoplasma Species in Cell Culture Contamination

| Mycoplasma Species | Primary Source | Approximate Frequency of Contamination |

|---|---|---|

| M. orale | Human | 20 - 40% [11] [26] |

| M. hyorhinis | Porcine | 10 - 40% [11] |

| M. arginini | Bovine | 20 - 30% [11] |

| M. fermentans | Human | 10 - 20% [11] [26] |

| M. hominis | Human | 10 - 20% [11] [26] |

| Acholeplasma laidlawii | Bovine | 5 - 20% [11] [26] |

Method Comparison: PCR vs. Culture for Mycoplasma Detection

The choice of detection method is critical for accurate and timely quality control. The following experimental data and protocols provide a direct comparison between the rapid, molecular-based PCR methods and the traditional, gold-standard culture approach.

Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

A definitive study conducted by the National Cell Bank of Iran offers a robust experimental framework for comparing detection techniques [11].

- Sample Preparation: Thirty cell lines suspected of mycoplasma contamination were selected. Prior to testing, each cell line was cultured in an antibiotics-free medium for at least 4-5 days without exchanging the medium to allow for potential mycoplasma proliferation [11].

- Control Groups: Five mycoplasma-contaminated cell lines were used as positive controls, and five mycoplasma-free cell lines served as negative controls to validate the results of each method [11].

- Compared Methods: Each cell line was evaluated in parallel using five different techniques:

- Microbial Culture: The direct culture method, considered the regulatory gold standard.

- Indirect DNA Staining (DAPI): A fluorescent dye that binds to DNA, revealing filamentous staining in the cytoplasm of infected cells.

- Enzymatic Assay (MycoAlert): A biochemical assay that detects mycoplasma-specific enzyme activity.

- Conventional PCR: A gel-based PCR method using genus-specific primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene.

- Real-time PCR (qPCR): A fluorescence-based PCR method that allows for real-time monitoring of amplification, also targeting the 16S rRNA gene [11].

Performance Data and Results

The study yielded clear, quantitative results on the efficacy of each method, as summarized below.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Mycoplasma Detection Methods [11]

| Detection Method | Contamination Detection Rate | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Culture | 33.33% | Not specified (Reference) | Not specified (Reference) | Not specified (Reference) |

| DNA Staining (DAPI) | 46.66% | Data not available in source | Data not available in source | Data not available in source |

| Enzymatic Assay | 53.33% | Data not available in source | Data not available in source | Data not available in source |

| Conventional PCR | 56.66% | 94.44% | 100% | 96.77% |

| Real-time PCR (qPCR) | 60.00% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

The analysis concluded that the real-time PCR assay was superior to all other methods, offering the highest sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy [11]. This superior performance is attributed to PCR's ability to correctly detect the infecting mycoplasmas at extremely low levels, with some nested PCR protocols capable of detecting as few as 1 CFU per 10^4 cells [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of either PCR or culture methods relies on a suite of specific reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the field at large.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mycoplasma Detection

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| MycoAlert Assay Kit | Enzymatic detection of mycoplasma contamination; measures ATP levels in sample. | Used as one of the five comparative methods in the National Cell Bank of Iran study [11]. |

| PromoKine qPCR Kit | Real-time PCR-based detection of mycoplasma DNA. | Used with proven 100% sensitivity and specificity for mycoplasma detection in cell cultures [11]. |

| Hoechst 33258 / DAPI Stain | Fluorescent DNA dyes for indirect staining of mycoplasma in cell cultures. | Used in DAPI staining method to visualize mycoplasma DNA in the cytoplasm of infected cells [27] [25]. |

| PowerSoil Pro DNA Kit | Automated extraction of high-quality microbial DNA from complex samples. | Used in a cosmetics QC study to extract bacterial and fungal DNA from enriched samples prior to rt-PCR [28]. |

| 16S rRNA Primers | PCR primers targeting conserved regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene for universal mycoplasma detection. | Designed for conventional PCR in the featured study; product size of 425 bp [11]. This target is highly conserved and allows for broad species detection [15]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Critical growth supplement for cell culture media; a potential source of bovine mycoplasma. | All cell culture media in the featured study were supplemented with 10-20% FBS [11]. Requires sourcing from certified, mycoplasma-free suppliers. |

| HJC0123 | HJC0123, MF:C24H16N2O3S, MW:412.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RBC10 | RBC10, MF:C24H25ClN2O2, MW:408.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The choice between quality control methods involves a trade-off between speed and regulatory acceptance. The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the two primary testing pathways.

Regulatory bodies worldwide, including the FDA and EMA, mandate testing for mycoplasma in cell banks, viral seeds, and bulk harvest materials [29] [26]. While traditional culture methods are often cited as the regulatory gold standard in pharmacopoeias (e.g., USP <63>, Ph. Eur. 2.6.7), their 28-day incubation period is a significant bottleneck [27] [26].

In conclusion, the data clearly demonstrates that real-time PCR is superior to culture-based methods in terms of speed, sensitivity, and accuracy for detecting mycoplasma contamination. While culture methods retain their place in regulatory compliance, the biopharmaceutical industry's drive for efficiency and safety is leading to the increased adoption and regulatory acceptance of robust, validated PCR assays. This is particularly critical for advanced therapies and time-sensitive products, where a 28-day wait for results is impractical. A comprehensive quality control strategy will leverage the strengths of both methods—using qPCR for rapid in-process control and culture as a definitive, long-term release test—to effectively mitigate the pervasive risk of mycoplasma contamination.

A Deep Dive into Testing Workflows: From Traditional Cultures to Modern Molecular Assays

For decades, microbial culture has served as the undisputed gold standard for detecting and identifying pathogens across clinical, pharmaceutical, and research settings. This method relies on allowing microorganisms to proliferate in specialized nutrient media, enabling both detection and subsequent analysis. Culture methods are particularly crucial for mycoplasma detection in cell cultures, where these minute, cell wall-deficient bacteria can persist as covert contaminants, potentially compromising years of research or biopharmaceutical production. The phrase "28-day process" references the standard incubation period mandated by major pharmacopoeias for mycoplasma testing, a timeline that underscores the method's thoroughness but also its most significant limitation—time. This guide objectively compares the performance of this traditional benchmark against modern molecular alternatives, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data necessary to inform their diagnostic strategies.

Core Principles of the Culture Method

The culture method's validity stems from its fundamental principle: supporting the replication of viable organisms. Unlike molecular methods that detect genetic material, culture demonstrates the presence of living, metabolically active pathogens. For mycoplasma, this involves using both broth and agar media formulated to provide the specific nutrients and environmental conditions these fastidious organisms require. Broth media, such as Friis broth, allow for the enrichment of even low levels of mycoplasma, while semi-solid agar media facilitate the formation of characteristic "fried-egg" colonies that are visible under microscopy. The extended incubation period—up to 28 days—is necessary because of the slow growth rate of many mycoplasma species; some contaminants may not be detectable until the final days of the protocol. This process is considered the definitive test for viability, as it confirms the presence of organisms capable of sustained propagation.

Experimental Protocol: The 28-Day Mycoplasma Culture Test

The following workflow details the standard operational procedure for mycoplasma testing using the culture method, as employed in diagnostic laboratories and quality control testing.

Diagram Title: 28-Day Mycoplasma Culture Workflow

Detailed Methodology

- Sample Inoculation: The test sample (e.g., cell culture supernatant, biological product) is inoculated into a liquid broth medium, typically in a ratio of 1:10 to 1:20 (sample:broth). Common broth media include Friis modification or Hayflick modification, which are enriched with serum, yeast extract, and other essential growth factors [30].

- Broth Enrichment Phase: The inoculated broth is incubated at 35-37°C for a minimum of 14 days, often extended to 21 days. This extended enrichment period is critical for amplifying low-level contaminants that would otherwise go undetected. Subcultures from the broth are performed onto agar plates at multiple time points (e.g., day 3-7 and day 14-21) to capture any growing mycoplasma.

- Agar Plating and Incubation: The subcultured agar plates are incubated under anaerobic or microaerophilic conditions at 35-37°C for an additional 7-14 days. The anaerobic environment is crucial for the growth of many mycoplasma species.

- Colony Observation and Identification: Following incubation, agar plates are examined microscopically at 100-200x magnification for the presence of characteristic mycoplasma colonies. These appear as granular, "fried-egg" colonies due to their central growth into the agar and superficial peripheral zone. The entire process, from inoculation to final reading, constitutes the 28-day duration that defines this gold standard method.

Performance Comparison: Culture vs. PCR

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics of the culture method compared to PCR-based diagnostics, drawing on data from multiple studies across different pathogen types.

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance Metrics of Culture vs. PCR

| Metric | Culture Method | PCR-Based Methods | Context of Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Gold Standard (Reference) | 58.33% - 99% [31] [32] [33] | Varies by sample type, pathogen, and protocol |

| Specificity | Gold Standard (Reference) | 77.78% - 100% [31] [34] [32] | Varies by sample type, pathogen, and protocol |

| Time to Result | 14-28 days [31] [30] | Hours to 1 day [34] [35] | Mycoplasma testing; other infections may differ |

| Viability Detection | Yes (Detects living organisms) | No (Detects genetic material) | Fundamental methodological difference |

| Strain Identification | Requires subculture & typing | Can be designed for specific strain detection | PCR panels can be tailored [34] |

Table 2: Operational Characteristics and Applications

| Characteristic | Culture Method | PCR-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Key Advantage | Confirms viability; broad-spectrum detection | Speed and high sensitivity [36] [35] |

| Primary Limitation | Lengthy turnaround time [31] | Cannot determine viability; limited by primer design [34] |

| Antibiotic Susceptibility | Possible (Phenotypic testing) | Not possible (Requires detection of resistance genes) [35] |

| Throughput Capacity | Low to moderate | High, with automation potential [36] |

| Optimal Use Case | Regulatory batch release; viability confirmation | Rapid screening; detecting non-culturable organisms [36] [34] |

A systematic review and meta-analysis of molecular tests for bloodstream pathogens found that compared to traditional phenotypic culture methods, PCR tests showed 92–99% sensitivity and 99–100% specificity for identifying bacteria and associated antimicrobial resistance genes [33]. However, a direct comparison for mycoplasma tuberculosis reported a lower PCR sensitivity of 58.33% with 77.78% specificity when using a specific buffer-based DNA extraction method, highlighting how protocol variations impact performance [31]. Another large-scale study on pulmonary tuberculosis reported significantly higher PCR sensitivity (93%) and specificity (84%) [32].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of the 28-day culture method requires specific, high-quality reagents to ensure reliable results. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Mycoplasma Culture Testing

| Research Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Enrichment Broth (e.g., Friis Medium) | Liquid medium for amplifying low levels of mycoplasma over 14-21 days. Contains serum, yeast extract, and other essential growth factors [30]. |

| Agar Plates (Semi-Solid Medium) | Solid medium for colony formation. Allows for visual identification of characteristic "fried-egg" morphology after 7-14 days of incubation. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme used in some DNA extraction protocols for PCR to digest proteins and release microbial DNA, facilitating subsequent amplification [31]. |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Short, specific DNA sequences designed to bind to and amplify target mycoplasma DNA regions in PCR-based methods [31] [34]. |

| Fluorochrome Dyes (e.g., Hoechst stain) | DNA-binding dyes used in indirect staining methods to visualize mycoplasma DNA adhered to infected host cells, though results can be equivocal [37]. |

The gold standard culture method, with its 28-day broth and agar cultivation process, remains an indispensable tool for confirming viable mycoplasma contamination, particularly in regulated environments like drug development and biopharmaceutical manufacturing. Its strengths of proven reliability and viability detection are counterbalanced by its protracted timeline. In contrast, PCR-based methods offer a powerful alternative with unmatched speed and high sensitivity, making them ideal for rapid screening and situations where time-to-result critically impacts decision-making [36] [34]. The evolving diagnostic landscape does not necessitate a wholesale replacement of one method by the other, but rather a strategic integration based on context. For many researchers and quality control professionals, the most robust strategy involves using PCR for rapid, sensitive screening during ongoing projects, while reserving the comprehensive 28-day culture as a definitive confirmatory test for final product release and regulatory compliance.

Within the context of mycoplasma testing research, the paradigm for pathogen detection is shifting from traditional culture-based methods to sophisticated nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAT). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) represent two powerful NATs that offer unparalleled speed, sensitivity, and specificity. This guide provides an objective comparison of qPCR and dPCR, detailing their principles, performance metrics, and experimental protocols. By summarizing key quantitative data and methodologies, we aim to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the information necessary to select the appropriate technique for their specific diagnostic and quantitative challenges.

The gold standard for mycoplasma detection has traditionally been microbial culture. However, this method is hampered by Mycoplasma's stringent growth requirements and slow replication rate, often requiring 1 to 3 weeks to obtain a result [38]. This delay is untenable in fast-paced environments like drug development and biomanufacturing, where timely contamination monitoring is critical.

Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques (NATs), particularly qPCR and dPCR, have emerged as superior alternatives for rapid detection. These methods bypass the need for cultivation, directly targeting the pathogen's genetic material to provide results in a matter of hours [38] [39]. Their high sensitivity and specificity make them indispensable for ensuring cell culture integrity, validating bioprocesses, and managing infectious diseases. The following sections delve into how these two advanced techniques achieve rapid and reliable detection.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Workflow

While both qPCR and dPCR amplify target DNA sequences enzymatically, their methods of quantification and data analysis differ fundamentally, leading to distinct advantages and applications.

How qPCR Works

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, monitors the amplification of a target DNA sequence in real time using fluorescence [40]. The process relies on the quantification cycle (Cq), which is the PCR cycle number at which the fluorescence intensity exceeds a background threshold. This Cq value is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial amount of target nucleic acid; a lower Cq indicates a higher starting concentration [39]. Quantification is achieved by comparing the Cq values of unknown samples to a standard curve generated from samples with known concentrations [39].

How dPCR Works

Digital PCR (dPCR) takes a different approach by partitioning a single PCR reaction into thousands of individual nanoliter-scale reactions [41]. This partitioning is achieved through microfluidic chips (cdPCR) or water-in-oil emulsion droplets (ddPCR) [41]. Following endpoint amplification, each partition is analyzed as either positive (containing the target sequence) or negative (lacking the target). The absolute concentration of the target nucleic acid, in copies per microliter, is then calculated directly using Poisson statistics, without the need for a standard curve [41] [42].

Visualizing the Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the core procedural differences between these two techniques.

Performance Comparison: qPCR vs. dPCR

The fundamental differences in how qPCR and dPCR operate translate into distinct performance characteristics, as summarized in the table below and supported by experimental data.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of qPCR and dPCR for Pathogen Detection

| Performance Characteristic | qPCR | dPCR | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle of Quantification | Relative (via Cq and standard curve) | Absolute (via Poisson statistics) | dPCR quantifies without a standard curve [41] [42]. |

| Dynamic Range | Wide (up to 7-8 orders of magnitude) [39] | Narrower than qPCR [41] | |

| Analytical Sensitivity (LoD) | ~10.8 copies/reaction for M. pneumoniae [43] | Higher sensitivity; ~2.9 copies/reaction for M. pneumoniae [43] | ddPCR identified one positive sample that was negative by qPCR [43]. |

| Precision with Inhibitors | Susceptible; Cq values and efficiency are affected [44] | Tolerant; quantification is less affected [41] [44] | In samples with contaminants, qPCR efficiency dropped to 67%, while ddPCR results remained stable [44]. |

| Precision for Low Abundance Targets | Higher variability (CV) for low target concentrations (Cq ≥ 29) [44] | Superior precision and reproducibility for low abundance targets [44] | For low-level targets, ddPCR produced more precise and statistically significant data [44]. |

| Ability to Detect Fold-Changes | Good for high-abundance targets | Superior for detecting small (<2-fold) changes in low-abundance targets [44] | ddPCR accurately quantified 2-fold dilutions in contaminated samples where qPCR failed [44]. |

A key application of these techniques is in monitoring mycoplasma contamination. A 2019 study optimized a direct qPCR protocol to detect mycoplasma in cell cultures without DNA purification, achieving results in just 65 minutes [45]. The protocol used a 52°C annealing-extension temperature and a 6 µl sample volume, demonstrating that direct qPCR could achieve higher sensitivity than qPCR with purified DNA, making it ideal for rapid contamination monitoring and treatment efficacy studies [45].

Experimental Protocols in Practice

To illustrate how these principles are applied in real-world research, below are summarized methodologies from key studies on mycoplasma detection.

Protocol 1: Direct qPCR for Mycoplasma Contamination Monitoring

This protocol [45] is designed for speed and simplicity, eliminating the DNA purification step.

- Objective: To directly detect Mycoplasma DNA in U937 suspension cell culture without DNA purification.

- Sample Preparation: Supernatant from Mycoplasma-infected U937 cell cultures was used directly as the PCR template.

- qPCR Reaction:

- Kit: PhoenixDx Mycoplasma Mix (Procomcure Biotech).

- System: Bio-Rad CFX Connect.

- Reaction Volume: 20 µL.

- Sample Volume: 6 µL of cell culture supernatant.

- Cycling Conditions:

- Annealing-Extension: 52°C for 20 seconds.

- Total Run Time: 65 minutes.

- Key Finding: The direct qPCR protocol with 6 µl of template showed nearly identical sensitivity to regular qPCR performed with DNA purified from a 60 µl sample, demonstrating its efficiency and high sensitivity for rapid monitoring [45].

Protocol 2: ddPCR for Absolute Quantification ofMycoplasma pneumoniae

This protocol [43] highlights the use of ddPCR for precise quantification in clinical specimens.

- Objective: Absolute quantification of M. pneumoniae in clinical samples to track disease severity and treatment efficacy.

- Sample Preparation: DNA was extracted from 200 µL of clinical samples (sputum, throat swabs) using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit and eluted in 150 µL [43].

- ddPCR Reaction:

- System: TargetingOne Digital PCR System.

- Reaction Volume: 20 µL.

- Master Mix: 15 µL reaction buffer, 2.4 µL of each primer (10 µM), 0.75 µL probe (10 µM), and DNase-free water.

- Cycling Conditions: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 60°C for 1 min.

- Droplet Generation & Reading: The reaction mix was partitioned into droplets using a droplet generator. After PCR, droplets were read using a droplet reader, and the target concentration was calculated using Poisson statistics [43].

- Key Finding: The bacterial load in patients with severe M. pneumoniae pneumonia was significantly higher than in patients with general infection, and loads decreased significantly after macrolide treatment, demonstrating the utility of ddPCR in monitoring therapeutic efficacy [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of qPCR and dPCR relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Kits for PCR-Based Detection

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Probe-based qPCR Kit | Provides high-specificity detection of target DNA through sequence-specific probes. | PhoenixDx Mycoplasma Mix for specific mycoplasma contamination monitoring [45]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Purifies and concentrates nucleic acid from complex biological samples, removing PCR inhibitors. | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit used to extract DNA from clinical samples for ddPCR [43]. |

| dPCR System | Partitions reactions and performs absolute quantification. | TargetingOne System and QX100/200 systems for ddPCR [43] [41]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | For RT-qPCR; synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates. | Essential for detecting RNA viruses or gene expression studies [46]. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction System | Automates the purification process, increasing throughput and reproducibility. | MagNA Pure 96 [38] and Panther Fusion [38] systems for high-throughput clinical diagnostics. |

| Dimericconiferylacetate | Dimericconiferylacetate, MF:C24H26O8, MW:442.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RB-005 | RB-005, MF:C21H35NO, MW:317.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Both qPCR and dPCR are powerful NATs that have revolutionized rapid pathogen detection, displacing slower culture-based methods in many applications. The choice between them depends on the specific requirements of the experiment:

- Choose qPCR for high-throughput, cost-effective screening where relative quantification is sufficient, and sample inhibitors are well-controlled. Its broad dynamic range and established protocols make it a workhorse for routine diagnostics and monitoring [39].

- Choose dPCR when absolute quantification is critical, particularly for targets with low abundance, or when high precision is needed to detect small fold-changes. Its resilience to inhibitors and lack of reliance on a standard curve make it ideal for analyzing complex samples and validating biomarkers [43] [41] [44].

In the context of mycoplasma testing, direct qPCR offers an optimal balance of speed and sensitivity for routine contamination checks [45], while dPCR provides a powerful tool for clinical research requiring precise quantification to assess bacterial load and treatment response [43].

In the field of microbiological testing, particularly for mycoplasma, the choice between traditional culture methods and modern molecular techniques like Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) has significant implications for research and drug development workflows. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two foundational methodologies, focusing on the critical practical metrics of turnaround time, hands-on time, and sample volume. The analysis is framed within the broader context of optimizing laboratory efficiency while maintaining diagnostic accuracy, enabling researchers and scientists to make informed decisions that align with their project requirements and resource constraints.

The following table summarizes the core workflow differences between culture and PCR methods, highlighting the distinct advantages each method offers across key operational parameters.

Table 1: Core Workflow Comparison Between Culture and PCR Methods

| Parameter | Culture Method | PCR Method |

|---|---|---|

| Total Turnaround Time | 18 hours to several weeks [9] [47] [31] | 5 hours to 2 days [9] [48] [49] |

| Typical Hands-on Time | High (multiple processing steps, subculturing) | Lower (automated nucleic acid extraction and amplification) |

| Sample Volume Requirements | Often higher (e.g., 25g for food samples) [50] | Can be very low (e.g., clinical swabs, body fluids) [31] |

| Key Workflow Limitation | Slow growth rate of fastidious organisms [34] [31] | Limited to detecting targeted pathogens in the panel [34] |

Quantitative Data Comparison

Data compiled from recent clinical and laboratory studies clearly quantify the performance differences between these two methodologies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Recent Studies

| Application / Study | Metric | Culture Method | PCR Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complicated UTI Management [9] [49] | Mean Turnaround Time | 104.4 hours | 49.68 hours |

| Complicated UTI Management [9] [49] | Clinical Success Rate | 78.11% | 88.08% |

| Automated Urine Culture System [47] | Time to Negative Result | 18-24 hours | 5 hours |

| Bacterial Meningitis Diagnosis [51] | Detection Rate in CSF | 3% (10/38) | 10% (38/38) |

| Listeria Detection in Food [50] | Performance in High-Background Microflora | Poor (many false negatives) | Excellent sensitivity |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To contextualize the data in the previous tables, this section outlines the standard experimental workflows for both culture and PCR methods as cited in the literature.

Conventional Culture Protocol for Mycobacteria

The following protocol, based on the study by Mshana et al., describes the gold standard culture method for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a process that can take several weeks [31].

Sample Processing:

- Decontamination & Homogenization: Clinical specimens (e.g., bronchoalveolar lavage, pleural fluid) are decontaminated and homogenized using the Petroff technique [31].

- Inoculation: The processed sample is inoculated onto solid culture media, such as Lewenstein-Jensen (LJ) slant medium [31].

- Incubation: The inoculated media is incubated at 37°C. Visible colonies of M. tuberculosis typically take 4 to 8 weeks or longer to appear due to the organism's slow growth rate [31].

- Identification: Once growth is observed, further biochemical tests and phenotypic analysis are required for definitive identification, adding additional time to the process [31].

Real-Time PCR Protocol for Bacterial Identification

This protocol, synthesized from multiple studies, describes a standard real-time PCR workflow for detecting bacterial pathogens, which can provide results within hours [48] [50] [51].

1. Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Method: DNA templates are extracted from clinical samples or enrichment broths. This can involve boiling samples with a reagent like PrepMan Ultra, followed by centrifugation to pellet debris [50]. Automated systems like the KingFisher Flex or STARlet are also used for higher throughput and consistency [52].

- Output: Purified DNA or crude lysate for amplification.

2. PCR Amplification and Detection:

- Reaction Setup: The extracted DNA is combined with a master mix containing PCR buffer, primers, nucleotides (dNTPs), Taq DNA polymerase, and a fluorescent probe [31].

- Thermocycling: The reaction is placed in a real-time PCR thermocycler (e.g., Bio-Rad CFX96). The instrument runs through 35-45 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension, during which the fluorescent signal is measured in real-time [52] [31].

- Result Interpretation: The cycle threshold (Ct) value, which indicates the amplification cycle at which the fluorescent signal crosses a predefined threshold, is determined. A positive result is confirmed based on the Ct value [52]. Under optimal conditions, the entire process from sample to result can be completed in as little as 4-6 hours [48].

Workflow Visualization

The fundamental difference between the two methods lies in their core processes: culture relies on biological amplification of the organism itself, while PCR relies on molecular amplification of genetic material. The following diagram illustrates this conceptual distinction.

Conceptual Workflow: Culture vs. PCR

The practical, step-by-step workflows for each method, as derived from the experimental protocols, are shown below. The contrast in complexity and number of steps is a key determinant of overall turnaround and hands-on time.

Procedural Workflow: Step-by-Step Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of either culture or PCR workflows depends on a suite of essential reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Culture Media (e.g., Oxford Agar, LJ Medium) | Supports growth of target organisms while inhibiting background flora. | Culture-based isolation and identification [50] [31]. |

| Listeria Enrichment Broth / Fraser Broth | Selective liquid medium for enriching low numbers of target bacteria. | Broth enrichment step in standard culture methods [50]. |

| PrepMan Ultra Reagent | Prepares crude DNA templates by boiling and lysing bacterial cells. | Rapid nucleic acid extraction for PCR [50]. |

| PCR Master Mix (Buffer, dNTPs, Taq Polymerase) | Provides the essential components for DNA amplification. | Real-time and conventional PCR assays [31]. |

| Specific Primer/Probe Sets (e.g., for IS6110, 16S rRNA) | Binds to and enables amplification of unique target DNA sequences. | Specific pathogen detection in PCR [52] [31]. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractors (e.g., KingFisher Flex, STARlet) | Automates the purification of nucleic acids from samples. | High-throughput, consistent PCR workflow [52]. |

| Real-time PCR Thermocyclers (e.g., QIAcuity, Bio-Rad CFX96) | Instruments that perform thermal cycling and fluorescent detection. | Quantitative real-time PCR analysis [52]. |

| 3-Methylglutaric acid-d4 | 3-Methylglutaric acid-d4, MF:C6H10O4, MW:150.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ROS inducer 4 | ROS inducer 4, MF:C49H62BrO4P, MW:825.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mycoplasma contamination represents a significant risk in biopharmaceutical manufacturing, potentially compromising both product safety and efficacy. These small, cell wall-less bacteria can evade standard sterility testing and are difficult to detect without specialized methods. Throughout the drug development process—from raw material qualification to final product release—controlling for mycoplasma is a critical regulatory requirement. The two primary methodological approaches for detection are traditional culture-based methods and molecular techniques based on Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Culture methods, historically the gold standard, rely on growing mycoplasma in specialized media. In contrast, PCR-based methods detect specific mycoplasma genetic sequences, offering a fundamentally different approach to contamination screening. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques across key biomanufacturing testing scenarios, supported by experimental data, to inform method selection by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Technical Comparison: PCR versus Culture Methods

The fundamental differences between PCR and culture methods lead to distinct performance characteristics. The table below summarizes their core technical principles and inherent advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of PCR and Culture Methods

| Feature | PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) | Culture-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Amplifies and detects specific DNA sequences | Relies on microbial growth in specialized media |

| Detection Target | Genetic material (DNA) | Viable, reproducing organisms |

| Time to Result | Hours to a single day [53] [54] | Several days to several weeks [53] [11] [54] |

| Sensitivity | Can detect low levels of genetic material; highly sensitive [55] [54] | Requires a sufficient number of viable organisms to form colonies; may miss low-level contamination [54] |

| Key Advantage | Speed, sensitivity, and ability to automate | Confirms microbial viability and can detect a broad range of cultivable species |

| Key Limitation | Cannot distinguish between viable and non-viable organisms; may yield false positives from dead microbes [54] | Time-consuming; cannot detect non-cultivable or slow-growing species [53] [54] |

Performance Data from Comparative Studies

Independent studies have consistently highlighted the performance differences between these two methods. A large-scale study on tuberculosis detection, which shares methodological parallels with mycoplasma testing, found that in-house PCR demonstrated a sensitivity of 77.5% and a specificity of 99.7% compared to culture [56]. A more focused study on mycoplasma detection in cell cultures revealed the clear superiority of molecular methods.

Table 2: Comparison of Mycoplasma Detection Methods in Cell Cultures (30 Samples) [11]

| Detection Method | Contamination Detection Rate | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Culture (Gold Standard) | 33.33% | (Baseline) | (Baseline) |

| Indirect DNA Staining (DAPI) | 46.66% | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Enzymatic Assay (MycoAlert) | 53.33% | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Conventional PCR | 56.66% | 94.44% | 100% |

| Real-time PCR | 60.00% | 100% | 100% |

This data demonstrates that real-time PCR is not only the most sensitive method, identifying contamination in 60% of cell lines, but it also achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity, meaning it correctly identified all positive and negative samples [11]. A separate study on genital mycoplasmas reported that a multiplex PCR assay showed a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 96% compared to culture [53].

Application Scenarios in the Biomanufacturing Workflow

Raw Material and In-Process Testing

During early production stages, the priority for raw material and in-process testing is often speed and sensitivity to enable rapid decision-making. PCR is exceptionally suited for this role.

- Speed of Results: PCR can provide results in hours, allowing for quicker assessment of raw materials like cell banks, viral seeds, and media components, or for monitoring bioreactors during production [53] [54]. This rapid turnaround helps prevent the use of contaminated materials and minimizes potential delays in production schedules.

- High Sensitivity: The ability of PCR to detect very low levels of microbial DNA makes it invaluable for identifying low-grade, early-stage contamination that could amplify later in the process [55] [11]. This is critical for in-process controls where catching contamination early can save a production batch.

Lot Release Testing

Lot release testing is the final quality control checkpoint before a drug product is released to the market. This phase is highly regulated, and the chosen methods must be validated to meet strict regulatory guidelines [57]. The requirements for this stage differ from earlier phases.

- Regulatory Context and "Full Verification": For final drug substance and drug product, release testing is a mandatory regulatory requirement to confirm identity, purity, and potency [57]. According to current quality systems, process validation is required where results cannot be "fully verified" by subsequent inspection and test. While statistical lot release testing is used, it is generally not considered a substitute for full process validation for commercial products [58].