Scaffold-Based 3D Spheroid Models: Enhancing Physiological Relevance in Cancer Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of scaffold-based three-dimensional (3D) spheroid models, which have emerged as indispensable tools bridging the gap between traditional 2D cell cultures and in vivo models.

Scaffold-Based 3D Spheroid Models: Enhancing Physiological Relevance in Cancer Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of scaffold-based three-dimensional (3D) spheroid models, which have emerged as indispensable tools bridging the gap between traditional 2D cell cultures and in vivo models. We explore the foundational principles demonstrating how these models more accurately mimic the complex tumor microenvironment, including cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, nutrient gradients, and drug resistance mechanisms. A detailed methodological analysis covers scaffold fabrication techniques, material choices, and specific applications across cancer types like osteosarcoma, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. The content further addresses common troubleshooting challenges and optimization strategies for generating consistent, high-quality spheroids, while presenting validation data comparing scaffold-based approaches to other 3D culture methods. This resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to implement and optimize these physiologically relevant models for improved preclinical screening and therapeutic development.

Why 3D Matters: The Scientific Foundation of Spheroid Models for Physiological Relevance

The Limitations of 2D Monolayers in Predicting Clinical Outcomes

In the pipeline of drug discovery and therapeutic development, preclinical testing serves as the critical gateway to human clinical trials. For decades, this testing has relied heavily on two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures, where cells are grown on flat, rigid plastic surfaces. While these systems have contributed fundamentally to our understanding of cellular biology, their ability to predict clinical outcomes in human patients remains profoundly limited. This discrepancy contributes significantly to the high attrition rates of candidate drugs, particularly in oncology, where the failure rate of oncology drugs in clinical development remains notably high. The fundamental issue lies in the vast physiological difference between the simplified 2D environment and the complex, three-dimensional (3D) architecture of human tissues. As research pivots toward more physiologically relevant models, 3D spheroid cultures have emerged as powerful tools that bridge the gap between traditional 2D monolayers and in vivo physiology. This review examines the core limitations of 2D monolayers and outlines how scaffold-based 3D spheroid techniques are advancing predictive accuracy in preclinical research.

Fundamental Limitations of 2D Monolayer Cultures

Altered Cell Morphology and Polarity

In vivo, cells exhibit complex 3D architectures and establish distinct apical-basal polarity, which is crucial for their specialized functions. The forced planar geometry of 2D monolayers disrupts this innate polarity, leading to aberrant cell spreading and flattened morphologies that do not reflect native tissue organization [1]. For instance, pancreatic β-cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) in 2D cultures predominantly display an immature phenotype, failing to achieve the full functional maturity seen in native islets, where 3D arrangement is critical for proper cell-cell connectivity and polarity [1]. This morphological distortion subsequently alters fundamental cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.

Loss of Native Tissue Microenvironment and Signaling

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a critical regulator of cancer progression and therapy response, comprising complex interactions between cancer cells, stromal cells, and the extracellular matrix (ECM). 2D models largely lack this complexity, as they are devoid of essential ECM components and the heterotypic cell-cell interactions present in vivo [2]. This simplified system fails to replicate the biochemical signaling gradients of growth factors, cytokines, and metabolites that drive tumor behavior and drug resistance. Consequently, drug responses observed in 2D monolayers often show poor correlation with in vivo efficacy, as demonstrated in ovarian cancer models where carboplatin response in 2D cultures correlated with in vivo results in only 3 out of 6 cell lines [2].

Absence of Physiological Gradients

Solid tissues and tumors in vivo are characterized by the presence of nutrient, oxygen, and metabolic waste gradients that arise from limitations in diffusion. These gradients create regional variations in proliferation, metabolic activity, and cell viability. In contrast, 2D monolayers provide largely homogeneous conditions where all cells are equally exposed to nutrients, oxygen, and tested compounds [3]. This fails to model the hypoxic cores commonly found in solid tumors, which are known to contribute to chemoresistance and are a key feature replicated in 3D spheroid models [3].

Inadequate Representation of Drug Penetration and Efficacy

The compact architecture of 3D tissues presents a physical barrier to drug penetration that is entirely absent in 2D monolayers, where drugs have direct and uniform access to all cells. This discrepancy leads to systematic overestimation of compound efficacy in 2D systems [3]. In vivo, drugs must traverse multiple cell layers and ECM barriers to reach their targets, a process directly modeled in 3D spheroids but not in 2D monolayers. Furthermore, the non-physiological cell-ECM interactions in 2D cultures alter the expression of drug transporters and efflux pumps, further skewing drug response data.

Table 1: Core Limitations of 2D Monolayer Culture Systems

| Limitation Category | Specific Deficiencies | Impact on Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|

| Architectural & Morphological | Altered cell shape and polarity; Loss of native 3D structure | Disrupted cell signaling and differentiation; Poor functional maturity |

| Microenvironmental | Lack of ECM; Absence of heterotypic cell interactions; Simplified cell-ECM signaling | Fails to model TME-mediated drug resistance; Altered gene expression profiles |

| Physiological Gradients | Homogeneous nutrient/O2 distribution; No metabolic waste gradients | Does not replicate hypoxic, quiescent, or necrotic zones found in vivo |

| Pharmacological Response | Uniform drug exposure; No penetration barriers; Altered adhesion-mediated survival | Overestimates drug efficacy; Fails to predict penetration-related resistance |

Quantitative Comparisons: 2D vs. 3D Model Performance

Direct comparative studies highlight the superior predictive value of 3D models for clinical outcomes. In a systematic investigation of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), the correlation between carboplatin responses in various preclinical models and in vivo mouse xenografts was quantitatively assessed [2]. The results demonstrated that 2D monolayer responses correlated with in vivo results in only 50% of tested cell lines (3/6). In contrast, 3D spheroid models showed correlation in 67% of cases (4/6), while ex vivo 3D micro-dissected tumor models correlated in 83% (5/6) [2]. This clear gradient of increasing predictive accuracy from 2D to 3D models underscores the critical importance of model dimensionality.

Similar trends have been observed in nanotoxicology studies. When A549 lung cancer cells and normal PC9 cells were treated with silver nanoparticles, significant differences in cytotoxicity were observed between 2D and 3D culture systems [4]. The 3D spheroids demonstrated notably different sensitivity profiles, with the spatial-temporal structure of the 3D environment playing a "pivotal role" in the inflammatory and cytotoxic responses [4]. This confirms that the dimensional context fundamentally alters cellular responses to external stimuli.

In neurological disease modeling, the limitations of 2D systems are particularly striking. The discordance between preclinical animal studies and human clinical trials for neurological disorders like Alzheimer's disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury has been substantial, with many drugs showing promise in 2D cultures and animal models failing in human trials [5]. This has driven the adoption of 3D brain organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which better recapitulate the complex cellular interactions and tissue architecture of the human brain [5].

Table 2: Correlation of Preclinical Models with In Vivo Therapeutic Response in Ovarian Cancer

| Preclinical Model Type | Correlation with In Vivo Response | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Monolayer | 50% (3/6 cell lines) [2] | Simple, cost-effective, high-throughput | Poor physiological relevance; No TME |

| 3D Spheroid | 67% (4/6 cell lines) [2] | Recapitulates some TME features; Gradient formation | Limited complexity; Variable reproducibility |

| 3D Ex Vivo Micro-dissected Tumor | 83% (5/6 cell lines) [2] | Preserves native TME and heterogeneity | Limited scalability; Technically challenging |

The Transition to Three-Dimensional Spheroid Models

Architectural and Functional Advantages of Spheroids

Spheroids are defined as spherical, self-assembled cellular aggregates that mimic key aspects of native tissue architecture. Their fundamental advantage lies in reestablishing physiological cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions that mediate tissue function and drug response [6]. Unlike 2D monolayers, spheroids develop distinct concentric zones that replicate the microenvironment of solid tumors: an outer proliferative zone, an intermediate quiescent zone, and a central necrotic or hypoxic zone [3]. This structural organization arises from the diffusion limitations of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic waste, closely mirroring the conditions found in avascular micro-regions of tumors.

The functional consequences of this 3D architecture are particularly evident in stem cell differentiation protocols. In pancreatic β-cell generation, transitioning from 2D to 3D culture systems has proven essential for achieving functional maturity of hPSC-derived β cells [1]. The 3D environment provides the necessary cell-ECM interactions and endocrine-to-endocrine cell contacts that drive the maturation of glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells, more closely mimicking the in vivo islet niche [1].

Enhanced Predictive Capacity for Drug Screening

The pharmacological response in 3D spheroids more accurately predicts in vivo outcomes because these models reintroduce critical drug penetration barriers and cell-ECM-mediated resistance mechanisms absent in 2D systems [3]. This is particularly valuable for screening chemotherapeutic agents, where penetration limitations significantly impact efficacy. The spatial organization of spheroids means that cells in different zones exhibit varying susceptibility to therapeutic agents, replicating the heterogeneous treatment responses observed in human tumors.

In the context of immunotherapy development, particularly for CAR-T cell research, 3D spheroid and organoid models provide a more physiologically relevant platform for evaluating efficacy [7]. Unlike 2D co-culture systems, 3D models incorporate immunosuppressive factors and stromal components of the TME that CAR-T cells must overcome in solid tumors, offering more predictive insights into clinical performance [7].

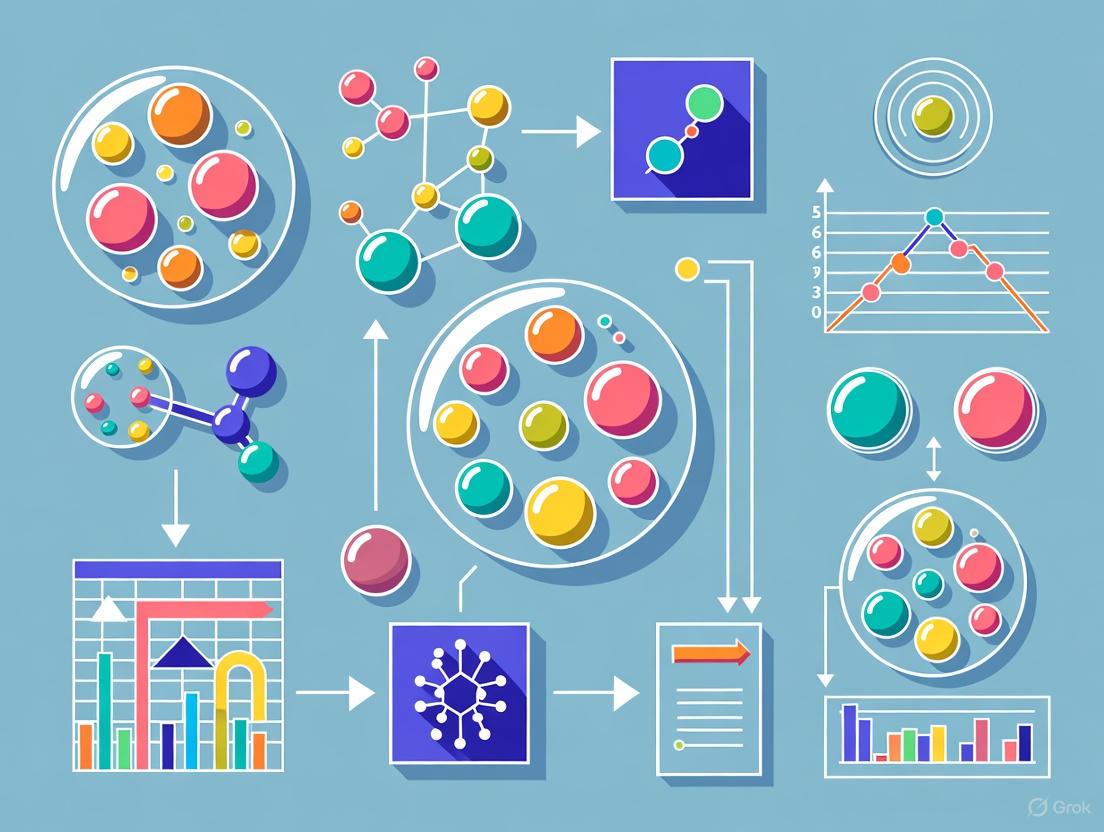

Diagram 1: Architectural and Functional Comparison Between 2D and 3D Models

Experimental Protocols for 3D Spheroid Generation and Assessment

Spheroid Formation Methodologies

Several well-established techniques enable reliable generation of 3D spheroids for research applications. The choice of methodology depends on the specific research requirements, including throughput, uniformity, and biological complexity.

Liquid-Overlay Techniques employ ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates with concave-bottom wells to promote cell aggregation by preventing adhesion to plastic surfaces. This method was utilized in ovarian cancer spheroid research, where 2,000-2,500 cells in 100 μL of complete medium were seeded per well of a 96-well ULA microplate, followed by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes to encourage aggregation [2]. Spheroids formed over 48 hours of incubation, reaching approximately 500 μm in diameter [2].

Hanging Drop Methods utilize surface tension to create suspended droplets containing cell suspensions, which aggregate at the bottom of the droplet to form spheroids. While this technique produces highly uniform spheroids, it has limitations in throughput and is less amenable to long-term culture due to evaporation.

Scaffold-Based Approaches employ natural or synthetic ECM materials such as Matrigel, collagen, or alginate to provide structural support that mimics the in vivo ECM. These systems are particularly valuable for incorporating multiple cell types and studying invasion. In micro-dissected tumor production for ovarian cancer research, tumor slices were processed using a McIlwain tissue chopper to obtain 350 μm thick sections, followed by creation of sphere-like micro-dissected tissues (MDTs) using a 500 μm biopsy punch [2].

Microfluidic and Bioprinting Technologies represent advanced approaches that enable precise spatial control over cell placement and the creation of complex, multi-cellular tissue architectures with perfusable vascular networks.

Key Assessment Methodologies for Spheroid Models

Viability and Cytotoxicity Analysis in spheroids requires specialized approaches adapted to 3D structures. The alamarBlue assay protocol has been optimized for drug dose-response determination in 3D tumor spheroids, addressing the diffusion limitations that can skew results in 3D systems [4]. Similarly, live/dead assays using fluorescent staining (e.g., calcein AM for live cells, ethidium homodimer for dead cells) provide spatial information on viability within different spheroid regions.

Morphometric Analysis of spheroid size, shape, and integrity provides critical data on growth dynamics and treatment effects. Brightfield microscopy enables routine monitoring, while automated image analysis systems can quantify parameters like spheroid area and circularity over time.

Histological and Immunofluorescence Techniques adapted for spheroid sections reveal internal architecture, proliferation gradients (via Ki-67 staining), hypoxic regions (via pimonidazole or HIF-1α staining), and protein expression patterns. These require specialized processing and sectioning protocols for 3D structures.

Molecular Analysis including RNA and protein extraction from spheroids presents technical challenges due to their compact nature, often requiring specialized dissociation protocols or laser capture microdissection for regional analysis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Spheroid Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Cultureware | Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates; Hanging Drop Plates | Prevents cell adhesion; Promotes 3D aggregation |

| Scaffold Matrices | Matrigel; Collagen I; Alginate | Provides ECM mimicry; Supports complex morphology |

| Extracellular Matrix Components | Laminin; Fibronectin; Hyaluronic Acid | Enhances physiological relevance; Influences cell signaling |

| Dissociation Agents | TrypLE; Accutase; Collagenase/Hyaluronidase mixes | Gentle spheroid dissociation for downstream analysis |

| Viability Assays (3D-optimized) | AlamarBlue; PrestoBlue; CellTiter-Glo 3D | Assess metabolic activity; Account for 3D diffusion |

| Histology Processing Kits | Spheroid Gel-Embedding Kits; Specialized Fixation Buffers | Preserves 3D structure for sectioning and staining |

Diagram 2: Standardized Workflow for 3D Spheroid Drug Testing

The limitations of 2D monolayer cultures in predicting clinical outcomes are extensive and well-documented, spanning architectural, microenvironmental, and pharmacological domains. The simplified geometry of 2D systems, combined with their absence of physiological gradients and inadequate representation of drug penetration barriers, fundamentally limits their translational relevance. The compelling evidence from comparative studies indicates that 3D spheroid models offer superior predictive value for clinical responses, particularly in complex disease contexts like oncology, neurology, and metabolic disorders.

The field continues to evolve with emerging technologies that further enhance the physiological relevance of 3D models. Organ-on-a-chip systems that incorporate fluid flow and mechanical stimulation, patient-derived organoids that capture individual tumor heterogeneity, and advanced bioprinting techniques that enable precise spatial control over multiple cell types represent the next frontier in predictive preclinical modeling [7]. These technologies, used in complementary fashion with simpler 3D spheroids, promise to further bridge the gap between in vitro models and human physiology.

As the scientific community increasingly recognizes the limitations of 2D monolayers, the transition to 3D model systems represents not merely a technical enhancement but a fundamental necessity for improving the efficiency of drug development and reducing late-stage clinical failures. The ongoing standardization of 3D culture protocols and analytical methods will be crucial for maximizing the potential of these advanced models to predict clinical outcomes accurately and transform the preclinical research landscape.

The development of effective anticancer drugs remains a major challenge, with only an estimated 5-7% of new oncology molecules successfully gaining clinical approval [8] [9]. The majority of drug candidates fail due to unanticipated toxicity and poor efficacy in human trials, often resulting from the low correlation between preclinical models and human pathophysiology [8]. This translational gap is largely attributed to the inability of traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems to reproduce the complex tumor architecture and cellular crosstalk that characterize human tumors in vivo [8] [10]. Over recent years, three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models have emerged as biologically relevant platforms that more accurately mimic the tumor microenvironment (TME), bridging the gap between conventional 2D cultures and in vivo animal models [8] [3].

This technical guide examines the core principles underlying the recapitulation of the TME in 3D models, with particular focus on spheroid models and scaffold-based techniques. We will explore the key cellular and non-cellular components of the TME, detail methodologies for reconstructing these elements in 3D systems, and provide practical protocols for researchers developing these models for drug discovery applications.

The Tumor Microenvironment: Composition and Significance

The tumor microenvironment is a highly heterogeneous and dynamic ecosystem consisting of both cellular and non-cellular components that collectively influence tumor progression, metastasis, and therapeutic response [10]. The accurate reproduction of these elements in vitro is essential for creating predictive cancer models.

Cellular Components

In solid tumors, the TME contains diverse non-cancerous cells that play active roles in all stages of tumorigenesis [10]. The table below summarizes the key stromal cell types and their functions in the TME.

Table 1: Key Cellular Components of the Tumor Microenvironment

| Cell Type | Primary Functions in TME | Impact on Tumor Progression |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) | Stimulate tumor cell proliferation via growth factor secretion; modify ECM; modulate inflammatory components [10]. | Drive tumor progression, metastasis, and angiogenesis [10]. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Interact with tumor cells via secretion of growth factors/cytokines; transfer mitochondria or microRNAs; form fibrovascular network [10]. | Can either promote invasion or inhibit tumor growth depending on context [10]. |

| Endothelial Cells | Form vascular network for nutrient delivery; protect tumor cells from immune system [10]. | Essential for tumor growth and metastasis; target for anti-angiogenic therapy [10]. |

| Pericytes | Stabilize blood vessel structure and permeability; serve as MSC reservoir [10]. | Influence tumor growth and metastasis through vessel stabilization [10]. |

| Immune Cells | Various functions including immune surveillance, phagocytosis, and antigen presentation [10]. | Can either inhibit or facilitate tumor growth depending on polarization [10]. |

Non-Cellular Components

The non-cellular compartment of the TME includes the extracellular matrix (ECM), which provides structural support and biochemical signals that influence tumor cell behavior [8] [10]. The ECM composition is dynamically remodeled in cancer, leading to altered stiffness and organization that promotes invasion and metastasis [10]. Additional non-cellular elements include oxygen gradients, pH variations, cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles that facilitate communication between tumor and stromal cells [10].

Core Principles of TME Recapitulation in 3D Models

Three-dimensional cancer models replicate critical features of the TME through several fundamental principles that distinguish them from traditional 2D cultures.

Architectural Organization

Unlike monolayer cultures where cells grow on flat, rigid surfaces, 3D models enable cells to establish spatial relationships and cell-cell contacts that mimic in vivo tissue organization [8] [3]. This 3D architecture influences critical cancer phenotypes including proliferation, differentiation, and drug response [8].

Gradient Formation

A defining characteristic of 3D models is their ability to establish physiochemical gradients of oxygen, nutrients, metabolites, and therapeutic agents [8] [3]. As in native tumors, these gradients create distinct microenvironments within the same structure, leading to the formation of concentric zones with different cellular states:

Stromal-Vascular Recapitulation

Advanced 3D models incorporate non-cancerous stromal cells to recreate the cellular heterogeneity of the TME [8] [10]. This includes cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), mesenchymal stem cells, endothelial cells, and various immune populations. The incorporation of vascular networks represents a particular challenge but is essential for modeling larger tissue constructs and simulating drug delivery [9].

Table 2: Comparison of 2D vs 3D Cancer Models for TME Recapitulation

| Feature | 2D Models | 3D Models |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Monolayer; forced apical-basal polarity [8] | Three-dimensional; natural cell orientation [8] |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to peripheral contacts [8] | Extensive 3D interactions mimicking in vivo [8] [3] |

| Cell-ECM Interactions | Artificial (plastic/glass surface) [8] | Physiological with natural or engineered ECM [8] |

| Proliferation Gradient | Uniform proliferation [8] | Zonal proliferation (outer > inner) [3] |

| Oxygen/Nutrient Gradients | Uniform distribution [8] | Physiological gradients from periphery to core [8] [3] |

| Drug Penetration | Immediate and uniform access [8] | Limited penetration mimicking in vivo barriers [8] |

| Stromal Component Integration | Challenging with limited functionality [8] | More physiological co-culture possible [8] [10] |

| Hypoxic Core | Absent [8] | Present in spheroids >400-500μm [8] [3] |

| Gene Expression Profile | Often altered due to unnatural substrate [8] | More closely resembles in vivo expression [8] |

| Drug Response Prediction | Poor clinical correlation [8] | Improved clinical relevance [8] |

Technical Approaches for 3D TME Modeling

Scaffold-Free Techniques

Scaffold-free methods rely on the innate tendency of cells to aggregate and form self-assembled structures, most commonly spheroids [9].

Spheroid Formation Methods

Forced-Floating/Liquid Overlay Technique: This method employs ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates coated with hydrophilic polymers that inhibit protein adsorption and cellular attachment [9]. The ease of preparation and compatibility with high-throughput screening make this approach particularly valuable for drug discovery applications [3] [9].

Hanging Drop Method: This technique involves suspending cell droplets from the lid of a culture plate, using surface tension to maintain the suspension while gravity promotes cell aggregation at the liquid-air interface [9]. While demonstrating approximately 90% reproducibility for multicellular tumor spheroid formation, challenges remain for medium exchange and integration with functional assays [9].

Agitation-Based Methods: These approaches use dynamic suspension cultures maintained through continuous orbital shaking, spinner flasks, or rotating wall vessels to prevent cell adhesion and promote aggregation [9].

Table 3: Scaffold-Free Spheroid Formation Techniques

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forced-Floating (Liquid Overlay) | Ultra-low attachment surfaces prevent adhesion [9]. | Simple; amenable to high-throughput screening; scalable [3] [9]. | Variable spheroid size/shape; reproducibility challenges [9]. |

| Hanging Drop | Gravity-induced aggregation in suspended droplets [9]. | High reproducibility (~90%); uniform spheroids [9]. | Difficult medium exchange; limited scalability for assays [9]. |

| Magnetic Levitation | Magnetic nanoparticle incorporation enables spatial manipulation [9]. | Precise spatial control; rapid aggregation [9]. | Potential nanoparticle toxicity; specialized equipment needed [9]. |

| Agitation-Based | Continuous motion prevents adhesion [9]. | Scalable for large spheroid production [9]. | Shear stress on cells; specialized equipment required [9]. |

Scaffold-Based Techniques

Scaffold-based approaches provide a biomimetic extracellular matrix (ECM) that supports 3D tissue formation and offers precise control over the biochemical and mechanical properties of the microenvironment [9].

Natural Polymer Scaffolds

Hydrogels derived from natural materials such as collagen, Matrigel, fibrin, and alginate are widely used for 3D cancer models [10]. These materials provide biological recognition sites that support cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation, closely mimicking the native ECM [10].

Synthetic and Hybrid Scaffolds

Synthetic polymers including PEG-based hydrogels and PLA/PLGA scaffolds offer enhanced tunability of mechanical properties and degradation kinetics but may lack natural cell adhesion motifs [10]. Hybrid approaches combining synthetic and natural materials provide a balance between controllability and bioactivity [10].

Vascularization Strategies

The incorporation of functional vasculature represents a significant advancement in 3D TME models, enabling the creation of larger, more physiologically relevant tissue constructs that overcome diffusion limitations [9].

Experimental Protocols for 3D TME Modeling

Protocol 1: Multicellular Spheroid Generation via Liquid Overlay Method

This protocol establishes a foundation for creating 3D tumor spheroids containing both cancer and stromal cells to model the cellular heterogeneity of the TME [3] [9].

Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for 3D TME Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment Plates | ULA plates with hydrophilic polymer coatings [9]. | Prevent cell adhesion and promote 3D aggregation [9]. |

| Basal Media | DMEM, RPMI-1640 [3]. | Provide essential nutrients for cell growth and maintenance [3]. |

| Supplementation | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS); growth factors [3]. | Support cell viability and proliferation [3]. |

| Stromal Cells | Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs); mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [10]. | Recapitulate tumor-stromal interactions [10]. |

| Endothelial Cells | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [10]. | Model vascular components of TME [10]. |

| Immune Cells | Macrophages, T cells [10]. | Reproduce immune context of TME [10]. |

| Extracellular Matrix | Collagen, Matrigel [10]. | Provide biomechanical and biochemical cues [10]. |

Procedure

Cell Preparation: Harvest and count cancer cells and stromal cells (e.g., CAFs, endothelial cells) at the desired ratio (typically ranging from 1:1 to 10:1 cancer:stromal cells) [10] [3].

Cell Seeding: Prepare a mixed cell suspension in complete medium at a concentration of 1-5 × 10⁴ cells/mL. Seed 100-200 μL per well in 96-well ULA plates [9].

Spheroid Formation: Centrifuge plates at 300-500 × g for 5-10 minutes to promote initial cell contact. Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 24-72 hours to allow spheroid consolidation [9].

Culture Maintenance: Carefully replace 50-70% of medium every 2-3 days without disrupting formed spheroids [9].

Quality Control: Monitor spheroid formation daily using brightfield microscopy. Well-formed spheroids should exhibit smooth, spherical morphology with compact structure [3].

Protocol 2: Vascularized 3D TME Model Using Bioprinting

This advanced protocol creates vascularized tumor models using 3D bioprinting technology, enabling the study of drug delivery and metastasis in a more physiological context [10] [9].

Materials and Reagents

- Bioink Components: Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), hyaluronic acid methacrylate (HAMA), or other photopolymerizable hydrogels [10]

- Vascular Cells: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human lung microvascular endothelial cells (HULEC), or induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells (iPSC-ECs) [10]

- Support Cells: Mesenchymal stem cells or pericytes [10]

- Bioprinter: Extrusion-based or light-based bioprinting system [10]

- Photoinitiator: Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) or Irgacure 2959 for crosslinking [10]

Procedure

Bioink Preparation: Mix tumor cells with bioink material at a density of 5-20 × 10⁶ cells/mL. Prepare separate vascular bioink containing endothelial cells and support cells at 10-30 × 10⁶ cells/mL [10].

Printing Process: Using a dual-printhead system, print the tumor compartment followed by the vascular network pattern. For extrusion printing, maintain pressure (15-30 kPa) and temperature (4-22°C) optimized for cell viability and printing resolution [10].

Crosslinking: Apply appropriate crosslinking method (UV light for photopolymerizable systems, ionic crosslinking for alginate-based systems) to stabilize the printed structure [10].

Maturation Culture: Transfer constructs to perfusion bioreactors if available, or use static culture with frequent medium changes. Culture for 7-14 days to allow vascular network maturation [9].

Validation: Assess vessel formation and functionality through immunohistochemistry (CD31 staining), dextran perfusion assays, and measurement of endothelial barrier function [9].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The enhanced physiological relevance of 3D TME models makes them particularly valuable for preclinical drug screening and development.

Drug Efficacy and Penetration Studies

Three-dimensional TME models enable the evaluation of drug penetration kinetics, a critical factor in anticancer drug efficacy that cannot be assessed in 2D systems [8] [3]. The presence of physiological barriers in 3D models, including compact tissue architecture and pressure gradients, more accurately predicts in vivo drug behavior [8].

Therapy Resistance Mechanisms

The zonal heterogeneity in 3D models recreates the subpopulations of tumor cells that contribute to therapy resistance in vivo [8] [3]. Quiescent cells in the intermediate zone and hypoxic cells in the core exhibit reduced sensitivity to conventional chemotherapeutics, mimicking the treatment-resistant populations observed in patient tumors [8].

High-Throughput Screening Compatibility

Adaptation of 3D models to high-throughput screening formats enables their application in large-scale drug discovery campaigns [8] [3]. Automated imaging and analysis systems allow for quantitative assessment of complex phenotypic responses in 3D contexts, providing more predictive data for lead optimization [8].

The recapitulation of the tumor microenvironment in 3D models represents a significant advancement in cancer research and drug development. By capturing the multicellular architecture, physicochemical gradients, and stromal interactions characteristic of in vivo tumors, these models provide a more physiologically relevant platform for studying tumor biology and therapeutic response. While challenges remain in standardization, vascularization, and scalability, ongoing technological innovations continue to enhance the fidelity and utility of 3D TME models. Their integration into the drug development pipeline promises to improve the predictive power of preclinical studies and ultimately increase the success rate of cancer therapeutics in clinical trials.

The evolution of three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models, particularly spheroids, represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, offering a critical bridge between traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayers and in vivo studies. Spheroids are spherical cellular aggregates that spontaneously self-organize, recreating cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions found in native tissues [3]. This architectural complexity enables the formation of physiological gradients—of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic waste—that drive the emergence of heterogeneous cellular zones mirroring those in solid tumors and tissues [11]. Within these zones, proliferating cells occupy the oxygen-rich outer layer, quiescent cells reside in an intermediate zone, and necrotic or apoptotic cells form a hypoxic core [3] [11]. This recapitulation of in vivo conditions has positioned spheroid models as indispensable tools for advancing cancer biology, drug discovery, regenerative medicine, and personalized therapeutic screening.

The fundamental distinction in spheroid generation lies in the use of external supporting matrices. Scaffold-based methods utilize a three-dimensional artificial matrix that mimics the native extracellular matrix (ECM), providing mechanical support and biochemical cues to promote cell aggregation and growth [11] [12]. These scaffolds can be derived from natural materials like collagen or Matrigel, or synthetic polymers such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). In contrast, scaffold-free methods rely on preventing cell-substrate adhesion, thereby forcing cells to aggregate via cell-to-cell contacts and secrete their own ECM components [12]. This forced self-assembly more closely replicates developmental processes like embryogenesis and organogenesis [12]. The choice between these approaches significantly influences spheroid properties, experimental outcomes, and translational potential, necessitating a clear understanding of their respective advantages and limitations.

Methodological Foundations: Techniques and Protocols

Scaffold-Based Spheroid Generation

Scaffold-based techniques provide a biomimetic environment that can be tailored to specific research needs. The foundational protocol involves embedding cells within a hydrogel or seeding them onto a pre-formed porous scaffold.

Natural Hydrogel Protocols: For Matrigel-based cultures, cells are suspended in chilled Matrigel and dispensed into culture plates. The plate is then incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes to allow polymerization before adding culture medium [13]. This method supports extensive outgrowth; for instance, merospheres and paraspheres embedded in Matrigel migrate outward to form epithelial sheets, while holospheres remain intact as stem cell reservoirs [14] [13].

Synthetic Scaffold Systems: Synthetic polymers like PEG or polycaprolactone (PCL) offer controlled mechanical properties and avoid batch-to-batch variability. Cells are typically mixed with polymer precursors and cross-linked to form a stable 3D network [11]. Recent advances include micropatterned PEG hydrogel plates that generate highly uniform spheroid arrays for high-throughput screening [12].

Microfluidic and Specialized Systems: "Organ-on-a-chip" microfluidic platforms incorporate continuous perfusion, creating dynamic physiological environments. These systems often contain microchannels coated with hydrogels that provide scaffolding while allowing precise control over the microenvironment [12].

Scaffold-Free Spheroid Generation

Scaffold-free methods promote spheroid formation through physical means that enhance cell-cell contact while minimizing cell-surface adhesion.

Liquid Overlay Technique: This widely used method employs plates coated with non-adhesive substrates, such as agar or agarose, or commercially available ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates. Cells are seeded and gravity-mediated aggregation forms spheroids within 24-72 hours [11]. The six-well ULA format generates heterogeneous spheroid populations (holospheres, merospheres, paraspheres), while 96-well ULA plates like BIOFLOAT and Elplasia produce highly uniform spheroids ideal for screening [14] [13].

Hanging Drop Method: Cells are suspended in droplets from a plate lid, with surface tension and gravity forcing aggregation into a single spheroid per droplet. This technique produces highly uniform spheroids without specialized equipment, though it can be labor-intensive [11].

Agitation-Based Methods: Techniques using rotating wall vessels or bioreactors maintain cells in suspension through continuous stirring, preventing adhesion and promoting aggregation. While simple, these methods can produce a broad size distribution and expose cells to shear stress [11] [12].

Emerging Technologies: Magnetic levitation and 3D bioprinting represent advanced scaffold-free approaches. Bioprinting, particularly the "Kenzan" method using microneedle arrays, positions spheroids as bioink units into predetermined architectures where they fuse into cohesive tissues [15].

Table 1: Standardized Protocols for Spheroid Formation

| Method | Key Reagents/Equipment | Protocol Summary | Incubation Time | Resulting Spheroid Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold-Based (Matrigel) | Matrigel, chilled tips, 37°C incubator | Suspend cells in chilled Matrigel, plate, polymerize at 37°C, then add medium [13] | 30 min polymerization + 48-72h culture | Integrated spheroids with outgrowth capacity; holospheres maintain stemness |

| Scaffold-Free (Liquid Overlay - 96-well) | ULA plates (e.g., BIOFLOAT, Elplasia) | Seed cell suspension (e.g., 5,000-50,000 cells/well in 50μL), incubate undisturbed [13] | 48 hours | Highly uniform spheroids; size controlled by initial seeding density |

| Scaffold-Free (Liquid Overlay - 6-well) | 6-well ULA plates | Seed 8,000 cells in 2mL medium per well, incubate undisturbed [13] | Several days | Heterogeneous populations: holospheres (408.7 μm²), merospheres (99 μm²), paraspheres (14.1 μm²) |

| Hanging Drop | Hanging drop plates or lid | Suspend cells in droplets (20-40μL), invert, culture | 3-5 days | Highly uniform spheroids, single spheroid per droplet |

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

Architectural and Functional Differences

The choice between scaffold-based and scaffold-free methods directly impacts spheroid architecture, gene expression, and drug response profiles. A head-to-head comparison of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) spheroids demonstrated that scaffold-based (SB) A549 spheroids developed larger diameters and elevated deposition of extracellular matrix compared to their scaffold-free (SF) counterparts [16]. This structural difference correlated with enhanced drug resistance, showing a trend of IC₅₀ (A549-SB) > IC₅₀ (A549-SF) > IC₅₀ (A549-2D) across five chemotherapeutics [16].

Both SF and SB spheroids displayed elevated expression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers and drug resistance-associated genes compared to 2D monolayers [16]. However, the enhanced resistance in SB spheroids was attributed not only to physiological barriers but also to the ECM acting as a physical barrier to drug penetration [16]. This highlights how the choice of spheroid production method can fundamentally influence the properties and drug responses of the resulting 3D model.

Applications Across Research Domains

Drug Screening and Development: Scaffold-free systems excel in high-throughput compound screening due to their scalability and reproducibility [3] [14]. The forced-floating and ULA plate methods predominate in this domain, with 96-well formats generating large numbers of uniform spheroids compatible with automated imaging and analysis pipelines [3] [13]. The physiological gradients in spheroids better predict drug penetration and efficacy, addressing the high failure rates of drugs that show promise in 2D models [12].

Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering: Scaffold-based approaches demonstrate particular utility in regenerative applications. For skin regeneration, Matrigel-embedded epithelial spheroids enable study of re-epithelialization and stem cell potential [14] [13]. In osteochondral regeneration, scaffold-free ES-MSC spheroids cultured in a customizable chamber system fused into integrated tissue constructs that successfully repaired cartilage defects in ex vivo models [17]. For complex organ regeneration, scaffold-free stem cell spheroids serve as bioink in bioprinting strategies, leveraging tissue self-assembly to create cohesive constructs without synthetic materials [15].

Personalized Medicine and Cancer Research: Patient-derived spheroids enable therapeutic testing tailored to individual patients. The five most investigated cancer origins for spheroid seeding are breast, colon, lung, ovary, and brain cancers [3] [18]. While scaffold-based methods provide microenvironmental context, scaffold-free approaches using forced-floating methods predominate for initial drug sensitivity testing due to their reliability and versatility [18].

Table 2: Functional Comparison of Scaffold-Based vs. Scaffold-Free Spheroid Models

| Parameter | Scaffold-Based Models | Scaffold-Free Models |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Recapitulates cell-ECM interactions; provides biochemical and mechanical cues [11] [12] | Enhanced cell-cell contacts; self-secreted ECM; mimics developmental aggregation [12] |

| Reproducibility & Uniformity | Batch-to-batch variability in natural scaffolds (e.g., Matrigel); more challenging to achieve uniformity [12] | High reproducibility with commercial ULA plates; size control via seeding density [13] [12] |

| Drug Resistance Properties | Higher resistance (IC₅₀) due to combined physiological and ECM barriers [16] | Moderate resistance compared to 2D, but less than scaffold-based models [16] |

| Throughput Capability | Lower throughput; more suitable for mechanistic studies [14] | High-throughput compatible, especially 96-well ULA formats [3] [14] |

| Technical Complexity | Higher complexity; potential need for enzymatic digestion for spheroid recovery [12] | Simpler workflow; easily adaptable to existing lab routines [12] |

| Primary Applications | Regenerative medicine, mechanistic studies of cell-ECM interactions, migration studies [14] [13] | High-throughput drug screening, personalized medicine, fundamental tumor biology [3] [12] |

Technical Considerations and Standardization

Methodological Optimization and Enhancement

Several technical advancements have emerged to enhance spheroid formation and functionality. ROCK1 inhibition (using Y-27632) in scaffold-free keratinocyte cultures significantly enhances holosphere formation, preserves stemness markers (BMI-1+), and reduces premature differentiation [14] [13]. This treatment increases the proportion of holospheres from 11.3% to 23.8% while decreasing paraspheres from 67.9% to 49.5%, effectively shifting the population toward more stem-like spheroids with greater regenerative potential [13].

The standardization of culture conditions is critical for reproducibility. For high-throughput applications, 96-well platforms like Elplasia and BIOFLOAT generate spheroids with consistent circularity and size distribution [13]. Low-throughput six-well ULA plates produce heterogeneous populations that better reflect biological diversity but require more careful characterization [13]. Researchers must optimize cell seeding density specific to their cell type and platform, as this parameter directly determines final spheroid size and quality.

Analytical and Imaging Challenges

The 3D architecture of spheroids presents distinct challenges for analysis and imaging. Nutrient and oxygen gradients along with diffusion kinetics become significant factors as spheroid size increases, potentially creating microenvironments that differ from in vivo conditions [12]. Most traditional imaging systems and analysis protocols were designed for 2D cultures and may not adequately capture 3D complexity [12].

Advanced solutions include confocal microscopy for deep tissue imaging, high-content screening systems with 3D analysis capabilities, and computational methods for quantifying spatial heterogeneity. The development of standardized analytical pipelines remains an active area of innovation, essential for improving reproducibility and cross-study comparisons.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spheroid Generation and Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates | Minimize cell-surface adhesion to promote cell-cell aggregation | Scaffold-free spheroid formation; available in 6-well (for heterogeneity) and 96-well (for uniformity) formats [13] [12] |

| Matrigel | Natural basement membrane matrix providing ECM components and growth factors | Scaffold-based spheroid culture; supports stemness and outgrowth in regenerative studies [14] [13] |

| ROCK1 Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Inhibits Rho-associated kinase, reduces apoptosis, enhances stem cell survival | Improves formation and stemness preservation in scaffold-free epithelial spheroids [14] [13] |

| Elplasia 96-Well Microcavity Plates | Microcavity design guides single spheroid formation per well | High-throughput, uniform spheroid production for drug screening [13] |

| BIOFLOAT 96-Well U-Bottom Plates | Polymer-coated surface prevents cell attachment | Consistent scaffold-free spheroid formation with controlled size [13] |

| Synthetic Hydrogels (PEG-based) | Tunable synthetic polymers for customizable 3D microenvironments | Scaffold-based culture with controlled mechanical and biochemical properties [12] |

| Microfluidic Platforms | Perfused systems with microchannels for dynamic culture | "Organ-on-a-chip" applications; long-term spheroid culture with physiological flow [12] |

Visualizing Spheroid Methodology and Architecture

The following diagrams illustrate key concepts in spheroid biology and methodology, created using Graphviz with adherence to the specified color and formatting guidelines.

Figure 1: Cellular Zonation in Mature Spheroids

Figure 2: Methodological Workflow for Spheroid Generation

The strategic selection between scaffold-based and scaffold-free spheroid models must align with specific research objectives and practical constraints. Scaffold-free systems offer advantages in reproducibility, scalability, and ease of use for high-throughput applications like drug screening and personalized medicine. Conversely, scaffold-based approaches provide enhanced physiological context through engineered microenvironments, making them valuable for mechanistic studies and regenerative applications where cell-ECM interactions are paramount.

Future developments in spheroid technology will likely focus on standardization, automation, and enhanced physiological relevance. The integration of artificial intelligence for image analysis and data interpretation, advancements in bioprinting for precise spheroid positioning, and the development of more physiologically relevant synthetic matrices will address current limitations [19] [15]. Furthermore, the creation of multi-tissue systems through spheroid fusion and the incorporation of vascular networks represent critical steps toward engineering complex functional tissues [15]. As these technologies mature, spheroid models will increasingly bridge the gap between in vitro studies and clinical applications, accelerating drug development and advancing regenerative medicine.

Three-dimensional (3D) spheroid models have emerged as a transformative tool in experimental oncology and drug discovery, bridging the critical gap between traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and in vivo tumor biology. These scaffold-free cellular aggregates better replicate the complex in vivo cellular microenvironments of human tissues by promoting intricate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions that more accurately mimic pathological and physiological conditions [6]. The architecture of spheroids recapitulates essential tumor characteristics, including nutrient gradients, hypoxic cores, and heterogeneous cell populations, creating a more physiologically relevant system for evaluating therapeutic efficacy [20].

Within the context of scaffold-based techniques research, spheroids represent a sophisticated approach to modeling the 3D spatial organization of tumors without relying on exogenous scaffold materials. This technical guide examines the key advantages of spheroid models through the lens of three critical phenomena: drug penetration, resistance mechanisms, and cellular heterogeneity. By understanding and leveraging these aspects, researchers can design more predictive preclinical studies that ultimately enhance the translation of therapeutic candidates from bench to bedside, particularly in the field of personalized cancer medicine [18].

Key Advantage 1: Drug Penetration

The penetration of therapeutic compounds into solid tumors represents a fundamental challenge in oncology drug development. Spheroid models excel in quantifying this parameter by recreating the physical barriers and transport limitations characteristic of human tumors. Unlike monolayer cultures where cells are uniformly exposed to dissolved compounds, spheroids develop concentric zones with varying microenvironments that significantly influence drug distribution and efficacy.

Physiological Barriers to Drug Delivery

The multicellular architecture of spheroids generates diffusional limitations that closely mimic those observed in avascular tumor nodules or micrometastases. Therapeutic agents must traverse multiple cellular layers to reach the spheroid core, encountering progressively changing conditions including:

- Reduced oxygen tension and nutrient availability in central regions

- Accumulation of metabolic waste products such as lactic acid

- Altered pH gradients that can impact drug stability and activity

- Increased cell density and extracellular matrix deposition creating physical barriers to diffusion

These parameters collectively influence the pharmacokinetic profile of tested compounds in ways that cannot be captured in 2D culture systems [20]. The spatial heterogeneity of drug exposure within spheroids provides crucial information about a compound's ability to reach all target cells at effective concentrations.

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Several established protocols enable quantitative analysis of drug penetration in spheroid models. The standardized spheroid-based drug screening protocol involves initiating spheroids, treating them with serial dilutions of therapeutic compounds, and determining analytical endpoints including spheroid integrity and cell survival [20]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Spheroid Size Standardization: Maintaining consistent spheroid diameter (typically 200-500 μm) is critical for reproducible diffusion kinetics

- Treatment Duration: Exposure times must be sufficient to allow compound penetration to the core

- Analysis Techniques: Sectioning and staining of spheroids following treatment enables visualization of spatial distribution

- Viability Assessment: Multiparametric assays measuring both overall and zone-specific cell death

For penetration studies, fluorescently tagged compounds or combination with fluorescent viability dyes allow direct visualization of distribution patterns using confocal microscopy. The acquisition of z-stack images through the entire spheroid diameter enables 3D reconstruction of penetration profiles [21].

Table 1: Experimental Approaches for Assessing Drug Penetration in Spheroid Models

| Method | Key Readouts | Technical Considerations | Compatible Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confocal Microscopy with Fluorescent Tags | Spatial distribution, Penetration depth, Gradient formation | Requires fluorescent compounds or dyes; Tissue clearing may enhance resolution [21] | Live/dead staining, Compound autofluorescence |

| Sectioning and Staining | Zone-specific effects, Cellular response heterogeneity | Destructive method; Enables high-resolution histology | Immunofluorescence, H&E, TUNEL apoptosis assay |

| Multiparametric Viability Assays | Global vs. core-specific toxicity | Penetration of assay reagents must be considered | Acid phosphatase, AlamarBlue, PrestoBlue [21] |

| Mass Spectrometry Imaging | Absolute compound quantification, Metabolite distribution | Technically challenging; Provides untargeted spatial metabolomics | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) |

Key Advantage 2: Resistance Mechanisms

Spheroid models provide unique insights into the complex mechanisms underlying drug resistance, which remains a primary challenge in clinical oncology. The 3D architecture and heterogeneous microenvironment of spheroids promote the emergence of multicellular resistance phenotypes that more accurately reflect treatment failure in patients than conventional 2D models.

Molecular Drivers of Resistance

Research using integrated single-cell and 3D spheroid platforms has elucidated key molecular pathways contributing to therapy resistance. In lung cancer models, cisplatin-resistant subclones demonstrated elevated expression of drug efflux transporters including ABCB1 (MDR-1) and ABCG2, enhancing their capacity to expel chemotherapeutic agents [22] [23]. Additionally, resistant subclones showed upregulation of cancer stem cell (CSC) markers (OCT4, SOX2, CD44, CD133) and activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) programs, characterized by E-cadherin downregulation and increased Vimentin, N-cadherin, and Twist expression [22].

These molecular adaptations correlate with functional phenotypes including enhanced migratory capacity and invasive potential, mirroring the aggressive behavior observed in treatment-resistant tumors. The spheroid model maintains these resistance mechanisms during in vitro culture, enabling sustained investigation of resistant cell populations [23].

Experimental Evidence from 3D Models

Comparative drug sensitivity assessments between 2D and 3D culture systems consistently demonstrate enhanced resistance phenotypes in spheroids. In lung cancer studies, chemotherapeutic agents including Docetaxel and Alimta displayed significantly higher IC₅₀ values in 3D spheroids compared to 2D cultures, suggesting that 3D models better reflect clinical dosing requirements [22] [23]. Similarly, targeted therapies such as Giotrif (afatinib) and Capmatinib exhibited subclone-specific efficacy patterns in MPE-derived spheroids, with Holoclone populations showing particular resistance profiles [23].

This resistance profile is mediated through both cell-autonomous mechanisms (e.g., efflux pump expression, CSC properties) and non-cell-autonomous factors (e.g., limited drug penetration, hypoxic core, cell-cell signaling). The convergence of these mechanisms in spheroids creates a pathophysiologically relevant system for investigating resistance and developing strategies to overcome it.

Table 2: Experimentally Demonstrated Resistance Mechanisms in Spheroid Models

| Resistance Mechanism | Key Molecular Markers | Functional Consequences | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Efflux Transport | ABCB1 (MDR-1), ABCG2 upregulated [22] | Reduced intracellular drug accumulation | Combination therapy with efflux inhibitors |

| Cancer Stem Cell Enrichment | OCT4, SOX2, CD44, CD133 elevated [22] | Enhanced self-renewal, Tumor initiation capacity | CSC-targeted agents, Differentiation therapy |

| EMT Activation | E-cadherin ↓, Vimentin ↑, N-cadherin ↑, Twist ↑ [22] | Increased invasion, metastasis, and survival | EMT pathway inhibitors, Microenvironment modulation |

| Phenotypic Plasticity | Dynamic marker expression, Non-genetic adaptation [23] | Reversible resistance states, Tumor heterogeneity | Epigenetic modifiers, Intermittent dosing strategies |

Key Advantage 3: Cellular Heterogeneity

Intratumoral heterogeneity represents a defining feature of human malignancies and a significant obstacle to effective treatment. Spheroid models uniquely capture this complexity by supporting the coexistence of multiple cellular subpopulations with distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics within a single integrated system.

Modeling Subclonal Diversity

The integration of single-cell isolation techniques with 3D spheroid culture enables precise dissection of subclonal heterogeneity and its functional consequences. In lung cancer models, researchers have isolated and characterized distinct resistant subclones—Holoclone, Meroclone, and Paraclone—derived from a common A549 parental line following cisplatin selection [23]. These subclones demonstrate stable differences in:

- Morphological appearance and growth patterns

- Gene expression profiles including resistance markers

- Drug sensitivity spectra to conventional and targeted agents

- Differentiation capacity and stem-like properties

This subclonal diversity mirrors the heterogeneity observed in patient tumors, where minor resistant populations can ultimately drive disease progression and treatment failure. Spheroid models maintain these subpopulations in physiologically relevant proportions and spatial arrangements, enabling investigation of clonal dynamics under therapeutic pressure [22].

Technical Approaches to Heterogeneity Analysis

Several methodological innovations facilitate the study of cellular heterogeneity in spheroid models:

- Single-Cell Cloning and Expansion: Microchip-based isolation enables derivation of pure subclones from heterogeneous populations [23]

- Long-Term 3D Culture: Maintenance of subclones as spheroids preserves their phenotypic characteristics during experimental manipulation

- High-Content Imaging: Multiparametric analysis of spheroid structure and composition at single-cell resolution

- Molecular Profiling: Transcriptomic and proteomic characterization of distinct spheroid regions or isolated subclones

These approaches collectively enable researchers to deconstruct the cellular complexity of spheroids and attribute specific functional capabilities to defined subpopulations. This resolution is essential for understanding how minor cell populations can dictate therapeutic outcomes.

Technical Guide: Experimental Protocols

Standardized Spheroid Formation Protocol

Consistent generation of uniform spheroids is foundational to reproducible experimental outcomes. The following protocol outlines a reliable approach for spheroid formation using low-attachment surfaces:

Cell Preparation: Harvest cells using standard trypsinization procedures and prepare a single-cell suspension in complete growth medium. Determine cell concentration using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter.

Seeding Optimization: For initial experiments, test a range of seeding densities (500-10,000 cells/well) to identify optimal conditions for your cell type. Centrifuge the plate at low speed (150 × g for 5 minutes) to promote cell aggregation [21].

Spheroid Formation: Culture cells in round-bottom, low-attachment 96-well plates to promote spontaneous aggregation. The hydrophilic polymer-coated surface of plates such as Nunclon Sphera inhibits cell attachment, forcing cells to aggregate into a single spheroid per well [21].

Culture Maintenance: For long-term cultures (≥7 days), perform half-media changes every 2-3 days by carefully tilting the plate and aspirating half the supernatant without disturbing the settled spheroids. Add fresh pre-warmed media gently along the well wall [21].

Quality Control: Monitor spheroid formation daily using brightfield microscopy. Most cell types form compact spheroids within 24-72 hours, though some may require longer periods. Exclude wells with multiple aggregates or irregular morphology from analysis.

Drug Sensitivity Assessment in 3D Models

Evaluation of compound efficacy in spheroids requires specific methodological adaptations to account for their 3D architecture:

Spheroid Maturation: Allow spheroids to form for 3-5 days prior to drug treatment, ensuring establishment of relevant microenvironmental gradients.

Drug Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of test compounds in culture medium at 2× final concentration. Include appropriate vehicle controls.

Treatment Application: Carefully remove 50% of existing medium from each well and replace with an equal volume of 2× drug solution to achieve desired final concentration.

Exposure Duration: Typical treatment periods range from 72-144 hours, depending on compound mechanism and experimental objectives.

Viability Assessment:

- For metabolic assays (e.g., PrestoBlue, AlamarBlue), increase incubation times 2-4 fold compared to 2D protocols to allow sufficient reagent penetration [21]

- For imaging-based viability assessment, use fluorescent probes (e.g., Calcein-AM for live cells, ethidium homodimer for dead cells) with extended incubation periods

- Consider tissue clearing reagents (e.g., CytoVista) to enhance imaging depth and resolution for larger spheroids [21]

Data Analysis: Normalize treatment groups to vehicle controls and calculate IC₅₀ values using nonlinear regression models. Compare 3D results to parallel 2D experiments to identify compound-specific differences in efficacy.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of spheroid-based research requires specialized reagents and materials optimized for 3D culture applications. The following toolkit outlines essential components for spheroid formation, maintenance, and analysis:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Spheroid Models

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Attachment Plates | Nunclon Sphera 96-well U-bottom plates [21] | Promote spontaneous spheroid formation via inhibition of cell attachment | Round-bottom geometry encourages single spheroid formation per well |

| Extracellular Matrix | Cultrex Basement Membrane Extract, Matrigel | Scaffold-based spheroid formation, Invasion assays | Lot-to-lot variability; Potential biological activity [21] |

| Viability Assays | PrestoBlue HS, AlamarBlue HS, Acid Phosphatase Assay [20] | Metabolic activity measurement in 3D structures | Require extended incubation times for penetration [21] |

| Cell Staining Reagents | CellEvent Caspase 3/7, MitoTracker Orange [21] | Apoptosis detection, Organelle-specific staining | Concentration often requires optimization for 3D (e.g., 2X for MitoTracker) [21] |

| Tissue Clearing Kits | Invitrogen CytoVista 3D Cell Culture Clearing/Staining Kit [21] | Enhance antibody and dye penetration for imaging | Enables high-resolution imaging to depths up to 1000 μm |

| Specialized Pipette Tips | Finntip wide orifice tips [21] | Spheroid transfer without structural damage | Essential for maintaining spheroid integrity during manipulation |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

Drug Resistance Mechanisms in Spheroid Models

Diagram 1: Resistance Mechanisms in Spheroids

Integrated Single-Cell to Spheroid Workflow

Diagram 2: Single-Cell to Spheroid Workflow

Spheroid models represent a sophisticated experimental platform that recapitulates critical aspects of in vivo tumor biology, particularly in the domains of drug penetration, resistance mechanisms, and cellular heterogeneity. By incorporating these 3D systems into preclinical drug development pipelines, researchers can obtain more clinically predictive data regarding compound efficacy and identify resistance mechanisms early in the development process. The technical protocols and reagent solutions outlined in this guide provide a foundation for implementing spheroid models in diverse research settings, with particular relevance for personalized medicine approaches using patient-derived materials. As standardization and accessibility of 3D culture technologies continue to improve, spheroid models are poised to play an increasingly central role in bridging the gap between traditional in vitro assays and clinical outcomes.

Building Better Models: Techniques and Applications of Scaffold-Based Spheroids

In the field of three-dimensional (3D) cell culture, scaffold-based techniques are fundamental for advancing spheroid models that better recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment. These scaffolds, whether derived from natural sources or synthetically engineered, provide the essential 3D architecture that supports cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, which are crucial for maintaining cellular phenotypes and functions not possible in traditional two-dimensional (2D) cultures [24] [6]. The selection between natural polymers like Matrigel and collagen and synthetic polymers such as PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) and PEG (poly(ethylene glycol)) represents a critical strategic decision in research design. This choice directly influences the biological relevance, reproducibility, mechanical stability, and experimental outcomes of spheroid studies [24] [25]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these material classes, equipping researchers with the data and methodologies needed to make informed decisions for their specific applications in cardiovascular biology, cancer research, and drug development.

Material Properties and Comparative Analysis

Natural Polymers: Matrigel and Collagen

- Matrigel: This is a basement membrane matrix extract derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma. It is a complex, biologically active mixture containing type IV collagen, laminin, entactin, and sulfated proteoglycans, along with various growth factors [26]. Its primary advantage is its high bioactivity, which promotes excellent cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. However, its animal-derived origin, batch-to-batch variability, and complex composition can be significant drawbacks for standardized studies [26] [13].

- Collagen: The most abundant protein in the human ECM, type I collagen is widely used for scaffold fabrication. It is biocompatible, biodegradable, and possesses cell-binding motifs (e.g., RGD sequences) that facilitate cell attachment [26] [27]. A key limitation is its poor mechanical behavior, leading to significant compaction under cellular forces, which can be mitigated by forming composites with other materials [26].

Synthetic Polymers: PLGA and PEG

- PLGA: A copolymer of lactic acid and glycolic acid, PLGA is a cornerstone of synthetic scaffold materials. Its key advantages include precise control over degradation rate (by adjusting the lactide:glycolide ratio), proven biocompatibility, and tunable mechanical properties [28] [27]. As a polyester, it degrades by hydrolysis into metabolites that enter the body's natural metabolic pathways [27]. Its potential drawbacks include hydrophobic surfaces that may require modification for optimal cell attachment and the possibility of eliciting acidic inflammatory responses during degradation [24] [27].

- PEG: Known for its high hydrophilicity and bio-inertness, PEG is often used to create hydrogels or as a block in copolymers (e.g., PLA-PEG). Its "blank slate" nature is a double-edged sword; it resists non-specific protein adsorption and cell attachment, which allows researchers to precisely engineer cell-material interactions by incorporating specific bioactive peptides. However, it lacks inherent bioactivity [28] [29].

Quantitative Material Comparison

The following tables summarize the key properties and parameters of these scaffold materials to facilitate direct comparison.

Table 1: Qualitative Comparison of Scaffold Material Properties

| Property | Matrigel | Collagen (Type I) | PLGA | PEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Natural (Murine) | Natural (Mammalian) | Synthetic | Synthetic |

| Bioactivity | High (Contains growth factors) | High (RGD motifs) | Low / Modifiable | Very Low / Engineerable |

| Mechanical Strength | Low (Soft hydrogel) | Low, prone to compaction [26] | High & Tunable [27] | Tunable |

| Degradation Rate | Enzymatic, Variable | Enzymatic, Relatively Fast | Hydrolytic, Tunable (weeks-months) [27] | Hydrolytic, Tunable |

| Batch-to-Batch Variation | High [13] | Moderate | Very Low | Very Low |

| Immunogenicity Risk | Moderate (Xenogeneic) | Low (if purified) | Low (can cause mild inflammation) [24] | Very Low |

| Key Advantage | Physiologically rich microenvironment | Excellent innate cellular recognition | Controllable properties & degradation | Precision and control over biofunctionalization |

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Scaffold Fabrication and Performance

| Parameter | Matrigel-Collagen Composite [26] | PLGA / PLA-PEG [28] | Ideal Scaffold Range (General) [25] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Polymer Conc. | 3-10 mg/mL (Collagen) | 10-20% (w/v) for electrospinning | Varies by method and material |

| Pore Size | Porous structure observed [26] | Nano-fibrous (via electrospinning) [28] | 150 - 500 μm (for cell infiltration & vascularization) [25] |

| Degradation Time | Not specified | Sustained release over 20 days [28] | Proportional to tissue formation rate [25] |

| Mechanical Properties (Tensile/Compressive) | Enhanced vs. collagen alone [26] | Tensile Modulus: ~35 MPa [28] | Matches target tissue (Bone: 1-20 GPa; Cardiac: 30-400 kPa) [25] |

| Water Absorption | Tunable swelling behavior [26] | Varies with PEG content | High porosity (>90%) for nutrient diffusion [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Spheroid Research

Protocol 1: Forming a Matrigel-Collagen Semi-IPN Scaffold for Dynamic Cell Culture

This protocol is adapted from studies on valve interstitial cells and demonstrates the formation of a composite hydrogel to improve the mechanical properties of collagen alone [26].

- Preparation of Stock Solutions: Prepare a sterile solution of Type I collagen (e.g., from rat tail tendon) in a weak acetic acid solution (e.g., 0.1% v/v). Thaw Matrigel on ice overnight.

- Neutralization of Collagen: Mix the cold collagen solution with the appropriate volume of neutralization buffer (e.g., 10X PBS) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) to achieve a physiological pH of 7.4. Keep everything on ice to prevent premature gelling.

- Forming the Composite Hydrogel: Rapidly mix the neutralized collagen solution with the thawed Matrigel at the desired volume ratio (e.g., 1:1 Matrigel:Collagen). Gently pipette to mix without introducing air bubbles.

- Polymerization: Transfer the mixture to the desired culture vessel (e.g., multi-well plate) and incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to allow a solid hydrogel to form.

- Cell Seeding and Culture: Seed the cell suspension directly on top of the pre-formed gel for a 3D overlay culture, or mix the cells with the composite solution before polymerization for 3D embedding. Add complete culture medium after the gel has set.

- Dynamic Mechanical Stimulation: Place the cultured scaffolds in a bioreactor system capable of applying cyclic mechanical strain (e.g., cyclic stretching) that mimics in vivo conditions, such as those found in cardiovascular tissues [26].

Protocol 2: Incorporating Spheroids into a Matrigel Scaffold for Invasion/Outgrowth

This protocol, derived from skin regenerative research, is used to study spheroid behavior and stem cell potential in a matrix-rich environment [13].

- Spheroid Generation: Generate epithelial spheroids using a scaffold-free method, such as culture in ultra-low attachment (ULA) 6-well plates. This produces a heterogeneous population of spheroids (holospheres, merospheres, paraspheres) [13].

- Matrigel Bed Preparation: Thaw Matrigel on ice. Carefully coat the wells of a pre-chilled culture plate with a thin layer of pure Matrigel and incubate at 37°C for 30 min to solidify.

- Spheroid Embedding: Resuspend the harvested spheroids in a small volume of cold Matrigel solution. Gently pipette this spheroid-Matrigel suspension on top of the pre-formed gel bed.

- Polymerization and Culture: Incubate the plate at 37°C for another 30 min to solidify the embedding layer. Once set, carefully overlay with complete culture medium.

- Analysis: Monitor spheroid behavior over time. Merospheres and paraspheres are expected to migrate outward, forming epithelial sheets, while holospheres may remain intact as stem cell reservoirs. Analyze using immunofluorescence for stemness markers (e.g., BMI-1) and imaging for migratory outgrowth [13].

Protocol 3: Fabricating a PLGA-PEG Nanostructured Scaffold for Gene Delivery

This protocol outlines the creation of a composite scaffold for sustained molecular release, such as DNA or growth factors, using electrospinning [28].

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve PLGA and a PLA-PEG block copolymer in a volatile organic solvent (e.g., hexafluoro-2-propanol, tetrahydrofuran) at a total polymer concentration of 10-20% (w/v). The ratio of PLGA to PLA-PEG can be varied (e.g., 85:15) to adjust fiber morphology and release kinetics.

- Functionalization: Add the bioactive agent (e.g., plasmid DNA) to the polymer solution and mix thoroughly to ensure a homogeneous distribution.

- Electrospinning Setup: Load the solution into a syringe with a metallic needle. Connect the syringe to a high-voltage power supply. Use a grounded collector drum or plate covered with aluminum foil to collect the fibers.

- Fabrication Process: Apply a high voltage (e.g., 15-25 kV) to the needle tip. Precisely control the flow rate of the polymer solution (e.g., 1.0 mL/h) using a syringe pump. The electrostatic forces will draw a jet of the solution towards the collector, forming solid, nano-fibrous scaffolds as the solvent evaporates.

- Post-Processing: Dry the fabricated scaffold under vacuum for 24-48 hours to remove any residual solvent.

- Release Study and Cell Culture: Sterilize the scaffold via UV irradiation. For release studies, incubate the scaffold in PBS at 37°C and collect supernatant at predetermined time points for analysis. For cell studies, seed cells directly onto the scaffold and assess transfection efficiency (if delivering DNA) and cell viability [28].

Visualizing the Scaffold Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making process for selecting between natural and synthetic polymers for spheroid research, based on the core experimental objectives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key materials and their functions for implementing the protocols discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Scaffold-Based Spheroid Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Type I Collagen (e.g., Rat Tail) | Forms the primary 3D hydrogel matrix for cell culture; provides biological cues for cell adhesion and proliferation. | Natural polymer, contains RGD sequences, thermo-reversible gelation at 37°C [26]. |

| Matrigel / Basement Membrane Extract | Creates a biologically active, complex hydrogel environment; used for stem cell culture, organoid formation, and invasion assays. | Rich in ECM proteins and growth factors; promotes complex tissue-specific morphogenesis [26] [13]. |

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | Synthetic polymer for fabricating durable, biodegradable scaffolds (fibrous meshes, porous foams) with controlled release properties. | Ester-linkage hydrolysis degradation; degradation rate tunable by LA:GA ratio [28] [27]. |

| PLA-PEG Block Copolymer | Used to create hydrogels or composite scaffolds; PEG enhances hydrophilicity, modulates release kinetics, and reduces protein fouling. | Amphiphilic nature; can be engineered for thermosensitive gelation (sol-gel transition) [28] [29]. |

| Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates | Generate scaffold-free spheroids for subsequent embedding in scaffolds or for comparative studies. | Covalently bonded hydrogel surface minimizes cell attachment, forcing cell aggregation into spheroids [13]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Enhances cell survival and stemness in spheroid cultures, particularly during the initial phases of aggregation and after dissociation. | Inhibits Rho-associated kinase; reduces anoikis (detachment-induced apoptosis) [13]. |