Setting Robust Acceptance Criteria for Method Comparability: A Risk-Based Framework for Biologics and ATMPs

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on establishing scientifically sound and defensible acceptance criteria for analytical method comparability and equivalency studies.

Setting Robust Acceptance Criteria for Method Comparability: A Risk-Based Framework for Biologics and ATMPs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on establishing scientifically sound and defensible acceptance criteria for analytical method comparability and equivalency studies. Covering the entire lifecycle from foundational principles to regulatory submission, it details a risk-based framework aligned with ICH Q5E and Q14. Readers will gain practical insights into statistical methods like the Two One-Sided T-test (TOST), strategies for batch selection and stability comparability, and best practices for troubleshooting and optimizing study designs to ensure robust demonstration of product quality and facilitate successful regulatory reviews.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Regulatory Expectations for Comparability

In the highly regulated pharmaceutical and biotech industries, ensuring the reliability and consistency of analytical methods is paramount. As drug development progresses and manufacturing processes evolve, scientists and regulators must frequently assess the relationship between different analytical procedures. Within this context, the terms "comparability" and "equivalency" represent distinct statistical and regulatory concepts with critical implications for product quality and regulatory compliance. While both concepts involve the assessment of methods or processes, they differ fundamentally in their stringency, statistical approaches, and regulatory consequences. Understanding this distinction is essential for designing appropriate studies, applying correct statistical methodologies, and navigating the regulatory landscape effectively throughout the analytical procedure lifecycle.

Core Definitions and Regulatory Context

Defining Comparability

Comparability refers to the evaluation of whether a modified analytical method yields results that are sufficiently similar to those of the original method to ensure consistent assessment of product quality. The objective is to demonstrate that the changes do not adversely impact the decision-making process regarding product quality attributes [1]. Comparability studies are typically employed for procedural modifications that are considered lower risk, such as optimizations within an established method's design space. These changes usually do not require prior regulatory approval before implementation, though they must be thoroughly documented and justified [1]. The statistical approach for comparability often focuses on ensuring that results are sufficiently similar and that any differences do not have a practical impact on quality decisions.

Defining Equivalency

Equivalency (or equivalence) represents a more rigorous standard, requiring a comprehensive statistical assessment to demonstrate that a new or replacement analytical procedure performs equal to or better than the original method [1]. Equivalency is necessary for high-risk changes, such as complete method replacements or changes to critical quality attributes. The key distinction lies in the regulatory burden: equivalency studies require regulatory approval prior to implementation [1]. The statistical bar is also higher, often requiring formal validation and sophisticated testing to prove that the methods are statistically interchangeable for their intended purpose.

The Regulatory Framework: ICH Q14 and Beyond

The ICH Q14 guideline on Analytical Procedure Development has formalized a structured, risk-based approach to the lifecycle management of analytical methods [1]. This framework encourages forward-thinking development where scientists define an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and anticipate future changes. Furthermore, other regulatory documents, such as the EMA Reflection Paper on statistical methodology and the USP <1033> chapter, provide additional guidance on the appropriate statistical approaches for demonstrating comparability and equivalency [2] [3]. The recent Ph. Eur. chapter 5.27 on "Comparability of Alternative Analytical Procedures" explicitly outlines the requirement for manufacturers to demonstrate that an alternative method is comparable to a pharmacopoeial method, a process that requires authorization by the competent authority [4] [5].

Key Distinctions at a Glance

The table below summarizes the critical differences between comparability and equivalency.

| Feature | Comparability | Equivalency |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Evaluation for "sufficiently similar" results [1] | Demonstration of "equal to or better" performance [1] |

| Regulatory Impact | Typically does not require prior approval [1] | Requires regulatory approval before implementation [1] |

| Statistical Stringency | Lower; focuses on practical similarity [1] [3] | Higher; requires formal proof of interchangeability [1] |

| Study Scope | Limited, risk-based testing [1] | Comprehensive, often full validation [1] |

| Typical Use Case | Minor method modifications, within design space changes [1] | Major method changes, method replacements [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Statistical Methodologies

Designing a Comparability Study

A comparability study is designed to show that a modified method does not yield meaningfully different results from the original. The protocol should include:

- Sample Selection: Analysis of a representative set of samples (e.g., drug product from different batches) using both the original and modified methods [1].

- Predefined Acceptance Criteria: Establishment of justified limits for the difference between method results based on the method's performance and the Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) it measures [1].

- Data Analysis: A comparison of the results, often through descriptive statistics and graphical analysis (e.g., difference plots, correlation coefficients). The focus is on showing that all differences fall within the predefined, practically significant limits.

Designing an Equivalency Study

An equivalency study demands a more rigorous statistical approach to prove that two methods are interchangeable.

- Side-by-Side Testing: A structured study analyzing a sufficient number of samples covering the expected range of the method using both the original and new procedures [1].

- Equivalence Testing using TOST: The preferred statistical method is the Two One-Sided T-tests (TOST) procedure [2]. This approach tests the hypothesis that the difference between the two method means is less than a pre-specified, clinically or quality-relevant equivalence margin (Δ).

- The null hypotheses (H₀) are: H₀₁: μ₁ - μ₂ ≤ -Δ and H₀₂: μ₁ - μ₂ ≥ Δ.

- The alternative hypotheses (H₁) are: H₁₁: μ₁ - μ₂ > -Δ and H₁₂: μ₁ - μ₂ < Δ.

- Equivalency is concluded only if both null hypotheses are rejected, demonstrating that the true difference is conclusively within the range -Δ to +Δ [2].

- Confidence Interval Approach: Equivalency can also be demonstrated by showing that the (1-2α)% confidence interval (e.g., a 90% CI for an α=0.05) for the difference in means lies entirely within the equivalence interval (-Δ, +Δ) [2].

Setting Risk-Based Acceptance Criteria

Setting the equivalence margin (Δ) is a critical, risk-based decision. Scientific knowledge, product experience, and clinical relevance must be considered [2]. As outlined in BioPharm International, risk-based acceptance criteria can be categorized as follows [2]:

- High Risk: Allows only a small practical difference (e.g., 5-10% of the tolerance or specification range).

- Medium Risk: Allows a moderate difference (e.g., 11-25%).

- Low Risk: Allows a larger difference (e.g., 26-50%).

This ensures that the most critical methods, where a small deviation could significantly impact product quality or patient safety, are held to the most stringent standard.

Workflow and Decision Pathways

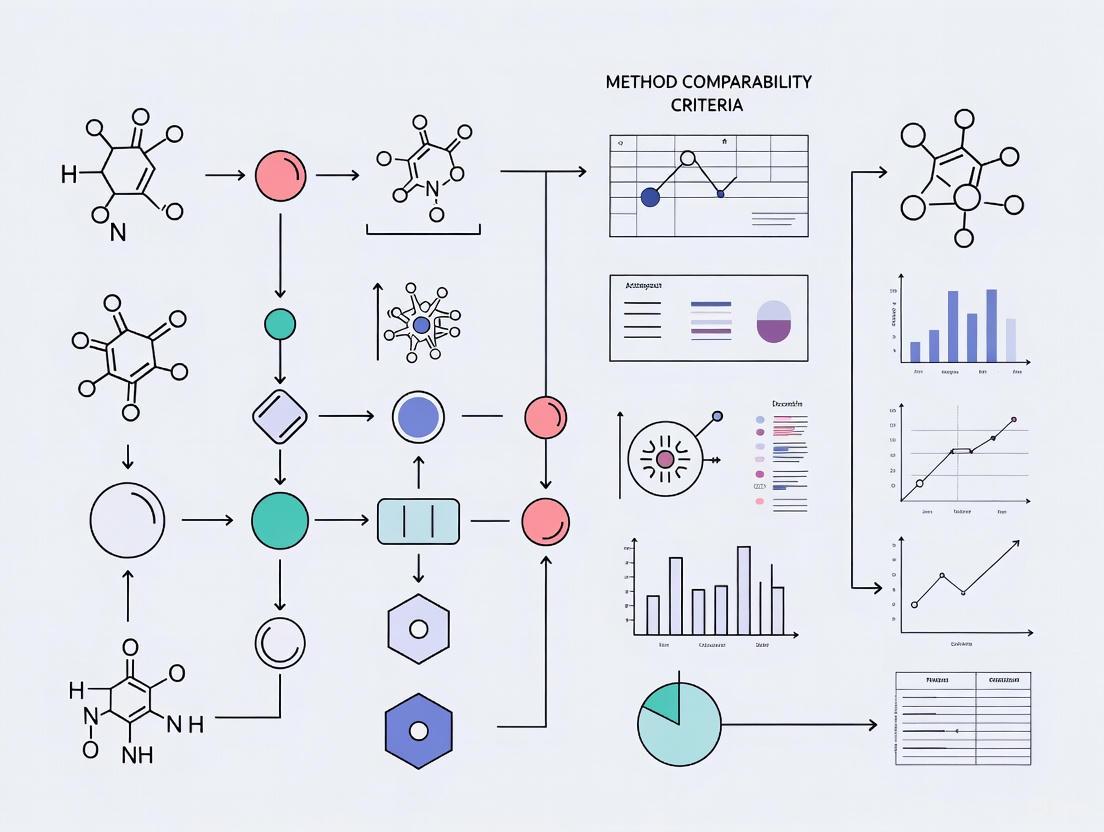

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for determining whether a comparability or equivalency study is required and the key steps involved in the assessment.

Decision Workflow for Method Changes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below details key reagents, materials, and solutions commonly required for conducting robust comparability and equivalency studies in an analytical laboratory.

| Item | Function in Comparability/Equivalency Studies |

|---|---|

| Representative Test Samples | A set of samples (e.g., drug substance, drug product from multiple batches) that accurately reflect the expected variability of the process. Essential for side-by-side testing [1]. |

| Reference Standards | Highly characterized materials with known purity and properties. Used to ensure both the original and new analytical procedures are calibrated and performing correctly [2]. |

| System Suitability Solutions | Prepared mixtures or solutions used to verify that the analytical system (e.g., HPLC, GC) is performing adequately before and during the analysis of study samples. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Commercially available materials with certified property values and uncertainties. Used to establish accuracy and traceability for quantitative methods. |

| Reagents and Mobile Phases | High-purity solvents, buffers, and other chemical reagents prepared according to strict standard operating procedures (SOPs) to ensure consistency and reproducibility across both methods. |

Navigating the concepts of comparability and equivalency is a fundamental requirement for successful analytical procedure lifecycle management in the pharmaceutical industry. The critical distinction lies in the regulatory and statistical burden: comparability demonstrates that methods are "sufficiently similar" for their intended purpose and is often managed internally, while equivalency demands rigorous statistical proof that methods are "interchangeable" and requires regulatory oversight. A deep understanding of these differences, coupled with the application of risk-based principles and appropriate statistical tools like equivalence testing (TOST), empowers scientists to make sound, defensible decisions. This ensures that changes to analytical methods enhance efficiency and innovation without compromising the unwavering commitment to product quality and patient safety.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three key regulatory frameworks—ICH Q5E, FDA Comparability Protocols, and ICH Q14—that are essential for managing changes in the biopharmaceutical development lifecycle. It is designed to help researchers and scientists establish robust method comparability acceptance criteria.

Comparative Framework of Regulatory Guidelines

The table below summarizes the core focus, scope, and application of ICH Q5E, FDA Comparability Protocols, and ICH Q14.

| Guideline | Primary Focus & Objective | Regulatory Scope & Application | Key Triggers & Context of Use | Core Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICH Q5E | Assessing comparability before and after a manufacturing process change for a biologic drug substance or product [6]. | Quality and patient safety; focuses on the biologic product itself [6]. | Post-approval manufacturing changes (e.g., process scale-up, site transfer) [6]. | Extensive analytical characterization (identity, purity, potency), and often non-clinical/clinical data [6]. |

| FDA Comparability Protocols | A pre-approved plan for assessing the impact of future manufacturing changes on product quality [6]. | A submission and review tool within a BLA/IND; outlines studies for future changes [6]. | Anticipated changes (e.g., raw material supplier, equipment) [6]. | Studies defined in the pre-approved plan (e.g., side-by-side analytical testing) [6]. |

| ICH Q14 | Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management, ensuring methods are robust and fit-for-purpose [1] [7]. | Analytical methods used to control the product; enables a structured, science-based approach [1] [7]. | Analytical method development, modification, or replacement [1]. | Analytical Target Profile (ATP), method validation data, and control strategy [8] [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Comparability and Equivalency

This section details the methodologies for conducting key studies under these regulatory frameworks.

Protocol for Product Comparability (Aligned with ICH Q5E & FDA Protocols)

This protocol is designed to generate evidence that a manufacturing change does not adversely affect the drug product.

- 1. Hypothesis: The pre-change and post-change drug products are comparable in terms of critical quality attributes (CQAs), and the existing safety and efficacy profile is maintained.

- 2. Experimental Design & Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Manufacture multiple lots of the drug substance and drug product using both the pre-change (reference) and post-change (test) processes [6].

- Forced Degradation Studies: Stress both reference and test samples under various conditions (e.g., light, heat, pH) to understand and compare product degradation profiles [6].

- Orthogonal Analytical Testing: Perform a comprehensive panel of analytical tests on reference and test samples to compare CQAs. This includes, but is not limited to [6]:

- Identity: Amino acid sequencing, peptide mapping.

- Purity/Impurities: Capillary electrophoresis (CE-SDS), reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RP-LC), and asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) for aggregates [6].

- Potency: Cell-based bioassays or binding assays.

- Product Characteristics: Isoform profile, charge variants, and glycosylation pattern.

- 3. Data Analysis & Acceptance Criteria:

- Statistical Comparison: Use statistical tools (e.g., equivalence tests, t-tests) to quantitatively compare CQAs between reference and test groups [6].

- Acceptance Criteria: Predefine acceptance criteria based on process capability and historical data. The data must demonstrate that post-change product CQAs are within the qualified or validated ranges and are highly similar to the pre-change product [6].

Protocol for Analytical Method Equivalency (Aligned with ICH Q14)

This protocol is used to demonstrate that a new or modified analytical method is equivalent to or better than the original method.

- 1. Hypothesis: The new analytical procedure is equivalent to the original procedure, providing the same or superior reportable results for the same samples.

- 2. Experimental Design & Methodology:

- Sample Set Selection: Select a representative set of samples that covers the entire reportable range and includes different lots and strengths [1].

- Side-by-Side Testing: Analyze the selected sample set using both the original and new analytical methods under a pre-defined study protocol [1].

- Full Validation: Ensure the new method has undergone a full validation per ICH Q2(R2) to confirm its performance characteristics (accuracy, precision, specificity, etc.) are suitable for their intended use [1].

- 3. Data Analysis & Acceptance Criteria:

- Statistical Evaluation: Perform a statistical comparison (e.g., paired t-test, ANOVA) of the reportable results from both methods [1].

- Acceptance Criteria: Predefine equivalence margins. The study demonstrates equivalency if the results from the new method fall within the pre-defined acceptable range compared to the original method [1].

Decision Workflow for Navigating Regulatory Guidelines

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for determining the appropriate regulatory pathway when a change occurs during drug development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details key reagents and materials critical for executing the experimental protocols for comparability and equivalency.

| Item Name | Function & Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Well-Characterized Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for assessing the quality of both pre-change and post-change products and for qualifying new analytical methods [6]. |

| Critical Quality Attribute (CQA)-Specific Assays | A panel of orthogonal assays (e.g., CE-SDS, RP-LC, qPCR) used to fully characterize the drug product's identity, purity, potency, and safety [6] [8]. |

| Stressed/Forced Degradation Samples | These samples help reveal differences in product profiles between pre-change and post-change materials that may not be visible under standard conditions [6]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Materials | Qualified materials used to verify that an analytical system is functioning correctly and is capable of providing valid data for each experimental run [8]. |

| ATP-Defined Analytical Procedures | Procedures developed and controlled per ICH Q14, ensuring they are fit-for-purpose and generate reliable data for comparability and equivalency decisions [8] [7]. |

In the development of biologic therapeutics, the direct linkage between Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and methodological rigor forms the cornerstone of a science-based quality framework. According to ICH Q8(R2), a Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) serves as "A prospective summary of the quality characteristics of a drug product that ideally will be achieved to ensure the desired quality, taking into account safety and efficacy of the drug product" [9]. Within this framework, CQAs are defined as physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties or characteristics that should be within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality [9]. The identification and control of CQAs are therefore paramount to patient safety and therapeutic efficacy, requiring a risk-based approach to determine the appropriate level of analytical and procedural rigor throughout the product lifecycle.

The modern paradigm of Quality by Design (QbD) emphasizes a systematic risk management approach, starting with predefined objectives for the drug product profile [9]. This involves applying scientific principles in a stage and risk-based manner to enhance product and process understanding, ensuring reliable manufacturing processes and controls for a safe and effective drug. As the industry faces increasing complexity in therapeutic modalities and manufacturing processes, the imperative to logically connect CQA criticality with study design stringency has never been more pronounced.

The Analytical Framework: From CQA Identification to Control Strategy

Systematic CQA Identification and Risk Assessment

The process of CQA identification represents the foundational step in establishing a risk-based control strategy. ICH Q9 defines risk as the combination of the probability of harm, the ability to detect it, its severity, and the uncertainty of that severity [9]. The protection of the patient by managing the risk to quality should be considered of prime importance, placing patient safety at the center of all CQA assessments.

A practical classification scheme enables development teams to identify potential critical quality attributes early in clinical development, refining this understanding as process and product knowledge matures [9]. This iterative classification typically involves:

- Prior Knowledge Assessment: Leveraging literature and platform knowledge for similar modalities to identify potential CQAs before product-specific data is available.

- Risk Ranking and Filtering: Systematically evaluating quality attributes based on their impact on safety and efficacy, often using risk assessment tools such as Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA).

- Experimental Verification: Conducting structured studies to confirm the criticality of attributes and establish appropriate ranges that ensure product quality.

The bi-directional relationship between CQA identification and process understanding creates an iterative knowledge loop, wherein information from process and product development enhances understanding of CQAs, which in turn informs further process optimization [9].

Analytical Control Stringency and Lifecycle Management

Once CQAs are identified, an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and analytical control stringency plan must be developed [9]. The ATP, as defined in ICH Q14, consists of a description of the intended purpose of the analytical procedure, appropriate details on the product attributes to be measured, and the desired relevant performance characteristics with associated performance criteria [9]. The control stringency then determines which analytical procedures become cGMP specification tests and which are deployed for non-cGMP characterization and development studies.

The recently adopted ICH Q14 and its companion guideline ICH Q2(R2) recommend applying a lifecycle approach for analytical procedure development, validation, and monitoring [9]. This enhanced approach, while more rigorous initially, provides flexibility for continuous improvement and more efficient control strategy lifecycle management. The traditional definition of Analytical Control Strategy (ACS) has typically focused narrowly on procedural elements of an analytical method, but in the context of QbD, the scope expands significantly to include strategies for CQA identification and for when and how to apply analytical procedures based on criticality and relative abundance of product attributes [9].

Table 1: Analytical Control Stringency Application Based on CQA Criticality and Phase of Development

| CQA Criticality Level | Development Phase | Control Stringency | Typical Analytical Procedures | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (Direct impact on safety/efficacy) | Early (Preclinical-Phase II) | High | cGMP release and stability methods | Quantitative, validated for intended purpose |

| Late (Phase III-Commercial) | Very High | cGMP specification methods with tight controls | Fully validated per ICH guidelines | |

| Medium (Potential impact on safety/efficacy) | Early | Medium | Characterization and investigation methods | Quantitative with defined performance |

| Late | High | cGMP methods with appropriate monitoring | Fully validated with defined control strategies | |

| Low (Minimal impact on safety/efficacy) | Early | Low | Development and characterization studies | Qualitative or semi-quantitative data |

| Late | Medium | Periodic monitoring or classification tests | Study-specific validation |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparability and Equivalency

Designing Comparability Studies

In the dynamic environment of drug development, changes to analytical methods are inevitable due to technology upgrades, supplier changes, manufacturing improvements, or regulatory updates [1]. The ICH Q5E guideline requires that "the existing knowledge is sufficiently predictive to ensure that any differences in quality attributes have no adverse impact upon safety or efficacy of the drug product" [10]. Demonstrating "comparability" does not require the pre- and post-change materials to be identical, but they must be highly similar [10].

A well-designed comparability study for biologics typically comprises several key elements:

- Extended Characterization: Providing orthogonal analysis with finer-level detail than release methods, especially for CQAs.

- Forced Degradation Studies: Revealing degradation pathways through stress conditions beyond typical process ranges.

- Stability Studies: Assessing real-time and accelerated stability profiles of pre- and post-change materials.

- Statistical Analysis: Applying appropriate statistical methods to historical release data and comparability study results.

For early-phase development, when representative batches are limited and CQAs may not be fully established, it is acceptable to use single batches of pre- and post-change material with platform methods [10]. As development advances to Phase 3, extended characterization increases in complexity to include more molecule-specific methods and head-to-head testing of multiple pre- and post-change batches, ideally following the gold standard format: 3 pre-change vs. 3 post-change [10].

Demonstrating Method Equivalency

While comparability evaluates whether a modified method yields results sufficiently similar to the original, equivalency involves a more comprehensive assessment to demonstrate that a replacement method performs equal to or better than the original [1]. Such changes require regulatory approval prior to implementation and typically include:

- Side-by-Side Testing: Analyzing representative samples using both the original and new methods under standardized conditions.

- Statistical Evaluation: Employing appropriate statistical tools such as paired t-tests or ANOVA to quantify agreement between methods.

- Predefined Acceptance Criteria: Establishing thresholds based on method performance attributes and CQAs before study initiation.

- Risk-Based Documentation: Tailoring documentation and regulatory submissions to the criticality of the change and its potential impact on product quality.

ICH Q14 encourages a structured, risk-based approach to assessing, documenting, and justifying method changes [1]. For high-risk changes involving method replacements, a comprehensive equivalency study with full validation is often required to ensure the data used for comparison meets GMP standards.

Table 2: Experimental Design for Analytical Method Comparability and Equivalency Studies

| Study Component | Comparability Study | Equivalency Study |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Threshold | Typically does not require regulatory filings or commitments [1] | Requires regulatory approval prior to implementation [1] |

| Sample Requirements | Single or multiple representative batches [10] | Multiple batches (typically 3 pre-change vs. 3 post-change) [10] |

| Testing Scope | Extended characterization, forced degradation, stability [10] | Full validation plus side-by-side comparison with original method [1] |

| Statistical Rigor | Descriptive statistics, graphical comparison | Formal statistical tests (t-tests, ANOVA, equivalence testing) [1] |

| Acceptance Criteria | Qualitative and quantitative criteria for "highly similar" [10] | Predefined statistical thresholds for "equivalent or better" [1] |

| Study Duration | Medium-term (aligned with stability testing intervals) | Comprehensive, often longer-term to ensure robustness |

Visualization of the Risk-Based CQA to Study Rigor Framework

Logical Workflow for CQA-Based Study Design

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between CQA identification, risk assessment, and the implementation of appropriate analytical control strategies, culminating in method comparability assessments.

Extended Characterization and Forced Degradation Experimental Workflow

The following diagram details the experimental workflow for extended characterization and forced degradation studies, which are critical components of comparability assessments for biologics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of a risk-based approach to CQA assessment and method comparability requires specialized reagents and analytical tools. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for conducting rigorous comparability studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for CQA Assessment and Comparability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Critical Attributes for Comparability |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Calibrate analytical methods and serve as benchmarks for product quality attributes [9] | Well-characterized, high purity, established stability profile |

| Critical Reagents | Enable specific detection and quantification in bioassays and immunoassays | Specificity, affinity, consistency between lots |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Measure biological activity and potency for CQAs related to mechanism of action [11] | Relevance to mechanism of action, reproducibility, appropriate controls |

| Chromatography Columns | Separate and analyze product variants and impurities | Selectivity, resolution, retention time reproducibility |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Enable accurate mass determination and structural characterization | Mass accuracy, purity, compatibility with analytical system |

| Forced Degradation Reagents | Stress products to reveal degradation pathways and product vulnerabilities [10] | Purity, concentration accuracy, solution stability |

The imperative of a risk-based approach connecting CQAs to study rigor represents a fundamental principle in modern pharmaceutical development and quality assurance. By systematically linking the criticality of quality attributes to the stringency of analytical controls and comparability assessments, organizations can build robust, scientifically justified development strategies that ensure product quality while maintaining flexibility for continuous improvement.

ICH Q14 transforms how organizations approach analytical procedures, emphasizing long-term planning from the outset [1]. While cultivating a forward-thinking culture can be challenging, the benefits of a well-designed lifecycle management program are invaluable. With intelligent design, validations become seamless, and change management evolves from reactive to proactive, enabling analytical procedures to stay aligned with innovation while remaining fit-for-purpose throughout a product's lifecycle [1].

The convergence of enhanced regulatory frameworks, advanced analytical technologies, and risk-based decision-making creates an opportunity for organizations to demonstrate deeper product and process understanding. This knowledge ultimately strengthens the scientific basis for quality determinations and accelerates the development of safe, effective, and high-quality biologic therapeutics for patients.

In pharmaceutical development, demonstrating method comparability is a critical regulatory requirement. While traditional t-tests have long been used for statistical comparisons, they are fundamentally limited for proving practical equivalence. This guide examines the theoretical and practical superiority of equivalence testing, particularly the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure, for establishing method comparability. Through experimental data and regulatory context, we demonstrate why moving beyond simple significance testing is essential for robust analytical procedure lifecycle management.

The Fundamental Limitation of Traditional T-Tests

Traditional null hypothesis significance testing (NHST), such as the common t-test, poses a significant challenge for comparability studies. The standard t-test structure examines whether there is evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between methods. When the p-value exceeds the significance level (typically p > 0.05), the only statistically correct conclusion is that the data do not provide sufficient evidence to detect a difference—not that no difference exists [12].

This approach creates a fundamental logical problem for comparability studies. As noted in the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapter <1033>, "A significance test associated with a P value > 0.05 indicates that there is insufficient evidence to conclude that the parameter is different from the target value. This is not the same as concluding that the parameter conforms to its target value" [2]. The study design may have too few replicates, or the validation data may be too variable to discover a meaningful difference from the target.

Three critical limitations of t-tests for comparability assessment include:

- High variability masking: Excessive method variability can lead to non-significant p-values even when meaningful differences exist

- Sample size dependence: With extremely large sample sizes, trivial, practically irrelevant differences can become statistically significant

- Incorrect conclusion framing: Failure to reject the null hypothesis does not provide evidence for equivalence

Equivalence Testing: A Statistically Sound Framework

Equivalence testing reverses the traditional hypothesis testing framework, making it particularly suitable for comparability assessments. The goal is to demonstrate that differences between methods are smaller than a pre-specified, clinically or analytically meaningful margin [12].

The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) Procedure

The TOST procedure tests two simultaneous null hypotheses:

- H01: μ2 – μ1 ≤ -θ (The difference is less than or equal to the lower equivalence bound)

- H02: μ2 – μ1 ≥ θ (The difference is greater than or equal to the upper equivalence bound)

The alternative hypothesis is that the true difference lies within the equivalence interval: -θ < μ2 – μ1 < θ [13]. When both one-sided tests reject their respective null hypotheses, we conclude that the difference falls within the equivalence bounds, supporting practical equivalence.

Establishing Equivalence Boundaries

Setting appropriate equivalence boundaries (θ) is a critical, scientifically justified decision that should be based on:

- Risk to product quality: Higher risks allow only small practical differences

- Analytical method capability: The inherent variability of the method

- Clinical relevance: The impact on safety and efficacy

- Process capability: Potential impact on out-of-specification (OOS) rates [2]

Table 1: Risk-Based Equivalence Acceptance Criteria

| Risk Level | Typical Acceptance Range | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High | 5-10% of tolerance | Critical quality attributes with narrow therapeutic index |

| Medium | 11-25% of tolerance | Key analytical parameters with moderate impact |

| Low | 26-50% of tolerance | Non-critical attributes with wide specifications |

Experimental Design for Method Comparability

Statistical Protocol

A robust equivalence study for analytical method comparison should include the following elements:

Sample Size Planning: Based on the formula for one-sided tests: n = (t₁₋α + t₁₋β)²(s/δ)², where s is the estimated standard deviation and δ is the equivalence margin [2]. For medium-risk applications with alpha = 0.05 and power of 80%, a minimum sample size of 13 is often appropriate, with 15 recommended for additional assurance.

Experimental Execution:

- Analyze representative samples using both original and modified methods under identical conditions

- Ensure sample selection represents the entire specification range

- Use appropriate blocking to minimize confounding factors

- Maintain full GMP documentation throughout the process

Data Analysis Workflow

Comparative Experimental Data: T-Test vs. Equivalence Testing

Case Study: HPLC Method Transfer

An experimental comparison was conducted during the transfer of a stability-indicating HPLC method from R&D to a quality control laboratory. The critical quality attribute measured was assay potency (%) for 15 samples across the specification range (90-110%).

Table 2: Method Comparison Results for Assay Potency

| Statistical Test | Result | Conclusion | Statistical Evidence | Regulatory Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional t-test | p = 0.12 | No significant difference found | Weak (failure to reject null) | Questionable |

| TOST Procedure | p₁ = 0.03, p₂ = 0.04 | Equivalence demonstrated | Strong (rejection of both nulls) | Acceptable |

| 90% Confidence Interval | (-1.45, 1.89) within (-2.5, 2.5) | Clinical equivalence confirmed | Interval within bounds | Strongly supported |

Comparative Performance Across Multiple Attributes

Table 3: Multi-Attribute Method Comparability Assessment

| Quality Attribute | Risk Category | Equivalence Margin | Traditional t-test p-value | TOST Result | Correct Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | High | ±2.5% | 0.15 | Equivalent | TOST only |

| Impurities | High | ±0.15% | 0.08 | Equivalent | TOST only |

| pH | Medium | ±0.3 units | 0.03 | Equivalent | Both methods |

| Dissolution | Medium | ±5% | 0.22 | Not equivalent | TOST only |

| Color | Low | ±2 units | 0.41 | Equivalent | TOST only |

Regulatory Framework and Implementation Guidelines

ICH Guidelines and Lifecycle Management

The introduction of ICH Q14: Analytical Procedure Development provides a formalized framework for the creation, validation, and lifecycle management of analytical methods [1]. Within this framework, demonstrating comparability or equivalency becomes essential when modifying existing procedures or adopting new ones.

Comparability vs. Equivalency Distinction:

- Comparability: Evaluates whether a modified method yields results sufficiently similar to the original, ensuring consistent product quality

- Equivalency: A more comprehensive assessment demonstrating that a replacement method performs equal to or better than the original, often requiring full validation and regulatory approval [1]

Practical Implementation Strategy

For Low-Risk Changes: A comparability evaluation with limited testing may be sufficient when a method's range of use has been defined by robustness studies.

For High-Risk Changes: A comprehensive equivalency study must show the new method performs equal to or better than the original, typically requiring:

- Full validation of the new method

- Side-by-side testing with representative samples

- Statistical evaluation using TOST or similar methodology

- Predefined acceptance criteria based on method performance attributes and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) [1]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Materials for Analytical Method Equivalency Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Comparability Studies | Critical Specifications | Supplier Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Primary method calibration and system suitability | Certified purity, stability, traceability | Official compendial sources preferred |

| Chemically Defined Reagents | Mobile phase preparation, sample dilution | HPLC/GC grade, low UV absorbance, lot-to-lot consistency | Manufacturers with robust change control processes |

| Columns and Stationary Phases | Chromatographic separation | Column efficiency (N), asymmetry factor, retention reproducibility | Multiple qualified vendors to mitigate supply risk |

| Quality Control Samples | Method performance verification | Representative of product quality attributes, stability | Should span specification range (low, mid, high) |

| Forced Degradation Materials | Stress testing for stability-indicating methods | Controlled conditions (oxidative, thermal, photolytic, acidic, basic) | Scientific justification for stress levels and duration |

Logical Decision Framework for Method Changes

The transition from statistical significance to practical equivalence represents a fundamental shift in analytical science that aligns statistical methodology with scientific and regulatory needs. Equivalence testing, particularly through the TOST procedure, provides a statistically rigorous framework for demonstrating method comparability that traditional t-tests cannot offer. By implementing risk-based equivalence margins, appropriate experimental designs, and clear decision frameworks, pharmaceutical scientists can robustly demonstrate method comparability while maintaining regulatory compliance throughout the analytical procedure lifecycle.

From Theory to Practice: Designing and Executing a Comparability Study

In the highly regulated landscape of pharmaceutical development, establishing scientifically sound acceptance criteria is paramount for ensuring product quality, patient safety, and regulatory compliance. A one-size-fits-all approach to acceptance criteria is increasingly recognized as inefficient and scientifically unjustified, often leading to unnecessary resource allocation or inadequate risk control. The paradigm has decisively shifted toward risk-based approaches that tailor acceptance criteria according to the potential impact of changes on product quality, safety, and efficacy [14].

This guide frames the establishment of risk-based acceptance criteria within the broader context of method comparability research, providing a structured framework for pharmaceutical professionals to differentiate strategies for high, medium, and low-risk changes. By directly linking risk assessment to statistical confidence levels and sample sizing, organizations can make more informed decisions about which changes require rigorous testing and which can be managed with more efficient approaches [15] [14]. The fundamental principle is that the stringency of acceptance criteria should be proportional to the risk posed by the change, ensuring optimal resource allocation while maintaining robust quality standards.

Foundational Concepts: Risk Assessment and Statistical Underpinnings

Core Risk Assessment Methodology

A standardized risk assessment process forms the foundation for establishing appropriate acceptance criteria. The process typically involves these key stages [16] [17]:

- Risk Identification: Systematic brainstorming sessions with cross-functional stakeholders to identify potential risks associated with a change, categorizing them as strategic, operational, financial, or external [16].

- Risk Analysis: Evaluation of each risk's likelihood of occurrence and potential impact on project objectives, often using qualitative (High/Medium/Low) or semi-quantitative (1-5 or 1-10 scales) scoring [17].

- Risk Prioritization: Using a risk matrix to categorize risks as high, medium, or low based on their likelihood and impact scores, enabling focused resource allocation [16].

Statistical Foundation for Acceptance Criteria

Risk-based acceptance criteria are grounded in statistical sampling theory, which balances producer risk (α, probability of rejecting an acceptable lot) and consumer risk (β, probability of accepting a rejected lot) [14]. The Operating Characteristic (OC) curve visually represents this relationship, showing how a sampling plan performs across various possible quality levels [14].

Two primary sampling approaches inform acceptance criteria:

- Attribute Sampling: Uses pass/fail criteria and is simpler to implement but typically requires larger sample sizes to achieve statistical confidence [14].

- Variable Sampling: Uses quantitative measurements against numerical specifications, providing more information about lot quality and requiring fewer samples to achieve the same statistical confidence as attribute sampling [14].

Table 1: Key Statistical Parameters for Acceptance Criteria

| Parameter | Definition | Impact on Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha (α) | Producer's risk; probability of rejecting an acceptable lot | Lower α requires more stringent acceptance criteria |

| Beta (β) | Consumer's risk; probability of accepting a rejected lot | Lower β requires more stringent acceptance criteria |

| AQL | Acceptable Quality Limit; highest defect rate considered acceptable | Sets the quality standard for routine production |

| RQL | Rejectable Quality Limit; lowest defect rate considered unacceptable | Directly tied to patient risk; drives sample size requirements |

Risk Classification Framework for Changes

Defining Risk Levels for Changes

The first step in establishing risk-based acceptance criteria is categorizing changes according to their potential impact on product quality and patient safety. This classification directly determines the appropriate statistical confidence levels and sample sizes for testing [14].

- High-Risk Changes: Changes with potential for direct impact on product quality, safety, or efficacy. Examples include changes to drug substance synthesis, formulation modifications, or changes to primary container closure systems. These require the most stringent acceptance criteria with high statistical confidence [14].

- Medium-Risk Changes: Changes with potential indirect impact on product quality attributes. Examples include certain manufacturing process parameter changes or analytical method changes. These require balanced acceptance criteria with moderate statistical confidence [14].

- Low-Risk Changes: Changes with negligible impact on product quality. Examples include documentation changes or equipment changes with proven equivalence. These require streamlined acceptance criteria with focus on efficiency [14].

Risk Assessment and Treatment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic process for assessing risk levels and selecting appropriate acceptance criteria strategies:

Strategic Approaches by Risk Level

Strategy for High-Risk Changes

High-risk changes demand the most rigorous approach to acceptance criteria, with focus on patient safety and quality assurance. The strategy should include [14]:

- Statistical Confidence: Maintain both α and β at 5% to ensure 95% confidence and power, minimizing both producer and consumer risk [14].

- RQL Focus: Set stringent RQL targets (e.g., <1%) based on severity of potential harm to patients, making this the primary driver of sample size [14].

- Sample Size: Select larger sample sizes to achieve higher AQL values while maintaining RQL targets, reducing the chance of rejecting acceptable material [14].

- Variable Sampling: Prefer variable over attribute sampling plans to maximize information obtained from each unit tested [14].

Table 2: Acceptance Criteria Strategy by Risk Level

| Strategy Element | High-Risk Changes | Medium-Risk Changes | Low-Risk Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Confidence | 95% (α/β = 5%) | 90-95% (α/β = 5-10%) | <90% (α/β >10%) |

| RQL Target | Low (e.g., 0.1-1%) | Medium (e.g., 1-5%) | High (e.g., 5-10%) |

| Sampling Approach | Variable preferred | Variable or attribute | Attribute typically sufficient |

| Sample Size | Larger (justified by RQL) | Moderate | Minimal |

| Documentation | Extensive, with formal rationale | Standard documentation | Basic documentation |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing Acceptance Criteria

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for establishing statistically sound, risk-based acceptance criteria:

Define the Change Scope: Clearly document the proposed change and its potential impact on product Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs). Form a cross-functional team including quality, regulatory, manufacturing, and development experts [14].

Conduct Risk Assessment: Using a standardized risk assessment methodology (e.g., FMEA), score the change for severity, probability, and detectability. Classify as high, medium, or low risk based on predefined criteria [17].

Select Statistical Parameters: Based on risk classification, set appropriate α, β, and RQL values. For high-risk changes, maintain both α and β at 5%. Link RQL directly to the potential severity of patient harm [14].

Determine Sample Size: Using the selected RQL and β values, calculate the required sample size. For variable sampling, this typically requires 20-30 samples to achieve 5% RQL with 95% confidence. For attribute sampling, similar protection may require 59+ samples [14].

Establish Acceptance Criteria: Define specific numerical limits or pass/fail criteria based on the selected statistical approach. For variable plans, establish process capability (Cpk) or tolerance interval requirements. For attribute plans, define the maximum allowable failures [14].

Document and Justify: Formalize the complete acceptance criteria strategy in a controlled document, including the risk assessment, statistical justification, and sample size calculation. Obtain appropriate quality and regulatory approval [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Acceptance Criteria Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | (e.g., JMP, Minitab, R) For OC curve generation, sample size calculation, and data analysis | Must support variable and attribute sampling plan analysis; validation required for regulated environments |

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized materials with known properties for method validation and system suitability | Certified reference materials preferred; requires proper storage and handling |

| Risk Assessment Tools | (e.g., FMEA templates, risk matrices) For standardized risk scoring and classification | Should be company-approved and aligned with ICH Q9 principles |

| Data Integrity Systems | (e.g., ELN, LES) For capturing, storing, and reporting experimental data | Must meet 21 CFR Part 11 requirements for electronic records and signatures |

| Quality Management Software | For documenting acceptance criteria, deviations, and change control | Should integrate with existing quality systems and provide audit trails |

Implementation and Compliance Considerations

Regulatory Alignment and Documentation

Successful implementation of risk-based acceptance criteria requires careful attention to regulatory expectations and documentation practices. Key considerations include [15] [14]:

- Structured Documentation: Implement formal Risk Acceptance Criteria (RAC) documents that clearly define risk thresholds, authority levels, and review processes. These should be officially documented in policy documents to ensure consistency across teams [15].

- Regulatory Compliance: Ensure acceptance criteria approaches align with relevant regulatory requirements, such as 21 CFR 820.250, which requires valid statistical techniques for sampling plans [14].

- Cross-Functional Communication: Communicate RAC across all departments (IT, Finance, Operations) to ensure consistent understanding and application. Internal audits should regularly challenge whether accepted risks remain justified [15].

Post-Implementation Strategy

After establishing and implementing risk-based acceptance criteria, ongoing monitoring is essential [15]:

- Performance Monitoring: Track actual outcomes against acceptance criteria to validate statistical assumptions and refine approaches for future changes.

- Periodic Review: Establish a regular schedule (e.g., quarterly for high-risk, annually for lower-risk) to reassess accepted risks and criteria as business conditions and threat landscapes evolve [15].

- Process Optimization: Use control charts and trend analysis to potentially reduce testing requirements post-process validation, once sufficient data demonstrates process stability [14].

Establishing risk-based acceptance criteria represents a scientifically rigorous approach to managing changes in pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. By differentiating strategies for high, medium, and low-risk changes, organizations can better allocate resources, maintain regulatory compliance, and ultimately enhance patient safety. The framework presented in this guide—connecting risk assessment to statistical confidence levels and sample sizing—provides a actionable approach for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in method comparability studies.

As the pharmaceutical industry continues to embrace risk-based methodologies, the ability to justify acceptance criteria through statistical principles and patient-centric risk assessment becomes increasingly important. This approach not only satisfies regulatory requirements but also fosters a more efficient and science-driven quality culture within organizations.

Within method comparability acceptance criteria research, establishing equivalence between two methods or processes is a frequent and critical challenge. Traditional hypothesis significance tests (NHST), which aim to detect a difference, are fundamentally unsuited for this purpose. A non-significant p-value (e.g., p > 0.05) does not allow researchers to conclude that two methods are equivalent; it may simply indicate insufficient data to detect the existing difference [12] [2]. Equivalence testing, specifically the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure, directly addresses this need by statistically validating that two means differ by less than a pre-specified, clinically or analytically meaningful amount [13] [18]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of TOST versus traditional confidence intervals, offering experimental protocols and data interpretation frameworks essential for drug development professionals.

Conceptual Framework: TOST vs. Traditional Confidence Intervals

The Logic of the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST)

The TOST procedure operates by reversing the conventional roles of null and alternative hypotheses. It formally tests whether the true difference between two population means (μ₁ and μ₂) lies entirely within a pre-defined equivalence margin (-θ, θ) [13].

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The difference between the means is large and clinically unacceptable (i.e., μ₂ – μ₁ ≤ –θ or μ₂ – μ₁ ≥ θ).

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The difference between the means is small and practically negligible (i.e., –θ < μ₂ – μ₁ < θ).

The procedure conducts two separate one-sided t-tests against the lower and upper equivalence bounds. If both tests yield a statistically significant result, the null hypothesis of non-equivalence is rejected, allowing the researcher to conclude equivalence [13] [19]. The overall p-value for the TOST is taken as the larger of the two p-values from the one-sided tests [13].

The Confidence Interval Approach

A visually intuitive and statistically equivalent method involves constructing a 1 – 2α confidence interval for the mean difference. For a standard 5% significance level, a 90% confidence interval is constructed [13] [2]. Equivalence is concluded if this entire confidence interval falls completely within the equivalence margins (-θ, θ) [13] [20]. This approach is graphically summarized in the following decision logic diagram:

Experimental Protocols for TOST

Core Workflow for a Method Comparability Study

Implementing TOST requires a structured approach, from planning to execution. The following workflow outlines the key stages in a typical method comparability study, emphasizing the critical pre-specification of the equivalence margin.

Detailed Methodology

The protocol below is adapted from a cleanability assessment case study [18] and general guidance on comparability testing [2].

1. Objective: To demonstrate that the cleanability (measured as cleaning time) of a new protein product (Product Y) is equivalent to a validated reference product (Product A).

2. Experimental Design:

- Test and Reference: Product Y (test) vs. Product A (reference).

- Measurement: Cleaning time (in minutes) from a bench-scale model using spotted coupons.

- Sample Size: 18 independent replicates per product group, determined via a power analysis to achieve sufficient power (e.g., 80-90%) given the expected variability and the chosen equivalence margin [18] [2].

3. Data Collection:

- Cleaning times are recorded for each replicate in a randomized order to avoid bias.

- Data are collected in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP).

4. Statistical Analysis Plan:

- Equivalence Margin (θ): Justified from historical data on the reference product. For example, θ = 4.48 minutes, calculated as two times the upper 95% confidence limit for the standard deviation of Product A's cleaning times [18].

- Analysis Method: TOST with α = 0.05 (corresponding to a 90% confidence interval).

- Software: Analysis can be performed using specialized statistical software like JMP, R (with the

TOSTERpackage), or Excel add-ins like QI Macros or XLSTAT [18] [19] [21].

5. Acceptance Criterion: The two products are considered equivalent if the 90% confidence interval for the difference in mean cleaning times (Product Y - Product A) lies entirely within the interval (-4.48, 4.48) [18].

Comparative Experimental Data and Interpretation

Case Study Results and Analysis

The following table summarizes the outcomes from two real-world case studies applying the above protocol, demonstrating both successful and failed equivalence [18].

Table 1: TOST Analysis of Cleanability for Protein Products

| Product Comparison | Sample Size (each) | Mean Cleaning Time (min) | Difference (B - A) | 90% CI of Difference | Equivalence Margin (θ) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product A vs. Product B | 18 | A: 86.21, B: 152.85 | 66.64 min | (62.91, 70.36) | ±4.48 min | Not Equivalent. The entire CI is outside the margin [18]. |

| Product A vs. Product Y | 18 | A: 86.21, Y: 85.41 | -0.80 min | (-1.55, 0.06) | ±4.48 min | Equivalent. The entire CI is within the margin [18]. |

Interpretation of Outcomes

The case studies in Table 1 illustrate how the TOST procedure provides clear, defensible conclusions.

- Product A vs. Product B: The 90% confidence interval (62.91, 70.36) is far outside the equivalence margin of ±4.48. This leads to a rejection of the alternative hypothesis of equivalence. Furthermore, since the entire interval is positive, we can conclude that Product B is significantly more difficult to clean than Product A [18].

- Product A vs. Product Y: The 90% confidence interval (-1.55, 0.06) is completely contained within the equivalence margin of ±4.48. Therefore, the null hypothesis of non-equivalence is rejected, and it is concluded that the two products are equivalent in cleanability [18].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of equivalence studies requires both statistical rigor and high-quality experimental materials. The following table details key reagents and their functions in the context of a bioanalytical method comparability study.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Method Comparability Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard | A well-characterized material with a known property (e.g., concentration, potency) that serves as the benchmark for comparison in the equivalence test [2]. |

| Test Article / Sample | The new product, material, or method whose performance is being evaluated for equivalence against the reference standard. |

| Validated Analytical Method | The procedure (e.g., HPLC, ELISA) used to measure the critical quality attribute. It must be validated to ensure accuracy, precision, and specificity to generate reliable data [22]. |

| Control Samples | Samples with known values used to monitor the performance and stability of the analytical method throughout the experimentation process. |

Regulatory and Practical Considerations

Setting the Equivalence Margin

The single most critical step in designing an equivalence test is the prospective justification of the equivalence margin (θ). This is a scientific and risk-based decision, not a statistical one [2] [23].

- Risk-Based Approach: Higher risks to product quality, safety, or efficacy warrant tighter (smaller) equivalence margins. For example, a critical quality attribute may allow only a 5-10% shift, whereas a lower-risk parameter may allow 11-25% [2].

- Considerations for Justification:

- Clinical Relevance: What difference would have no impact on patient safety or efficacy?

- Process Capability: What shift in the mean would lead to an unacceptable increase in out-of-specification (OOS) rates? [2]

- Analytical Variation: The margin should be set relative to the measurement uncertainty or biological variability of the method [23].

- Historical Data: As in the cleanability case study, historical data from a controlled dataset can be used to set a margin that accounts for natural variability [18].

TOST in the Regulatory Landscape

Equivalence testing is firmly embedded in regulatory guidance for the pharmaceutical industry.

- The ICH E9 guideline recognizes TOST as the standard for testing equivalence [24].

- The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) explicitly recommends equivalence testing over significance testing for demonstrating conformance, stating that a non-significant p-value is not evidence of equivalence [2].

- Regulatory bodies like the FDA require equivalence testing for demonstrating bioequivalence, where the confidence interval for the ratio of means must fall within 80%-125% [23], and for assessing comparability after process changes [18] [2].

In the context of method comparability acceptance criteria research, the choice of statistical tool is paramount. Traditional hypothesis tests and their associated 95% confidence intervals are designed to find differences and are inappropriate for proving equivalence. The TOST procedure, with its dual approach of two one-sided tests or a single 90% confidence interval, provides a statistically rigorous and logically sound framework for demonstrating that differences are practically insignificant. By prospectively defining a justified equivalence margin, following a structured experimental protocol, and correctly interpreting the resulting confidence intervals, researchers and drug development professionals can generate robust, defensible evidence of comparability to meet both scientific and regulatory standards.

In the pharmaceutical industry, demonstrating comparability following a manufacturing process change is a critical regulatory requirement. The foundation of a successful comparability study lies in a scientifically sound batch selection strategy, which ensures that pre- and post-change batches are representative of their respective processes. According to ICH Q5E, comparability does not require the materials to be identical but must demonstrate they are highly similar and that differences in quality attributes have no adverse impact upon safety or efficacy [10]. The selection of an appropriate number of batches and ensuring their representativeness provides the statistical power and confidence needed to draw meaningful conclusions from comparability data. This guide objectively compares different strategic approaches, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize their study designs.

Regulatory and Scientific Foundations

Regulatory guidelines emphasize a risk-based approach to comparability study design. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) draft guideline on topical products recommends comparison of at least three batches of both the reference and test product, often with at least 12 replicates per batch [25]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) similarly recommends a population bioequivalence approach for comparing relevant physical and chemical properties in guidance for specific topical products [25].

The primary objective is to demonstrate equivalence through a structured protocol that includes defined analytical methods, a statistical study design, and predefined acceptance criteria [2]. The strategy must account for inherent process variability, distinguishing between:

- Inter-batch variability: The natural variation in quality attributes between different manufacturing batches.

- Intra-batch variability: The variation observed among individual units within a single batch [25].

Failure to adequately account for these variabilities in the batch selection strategy can lead to studies that lack the statistical power to demonstrate equivalence, potentially requiring costly study repetition or regulatory delays.

Quantitative Batch Selection Recommendations

The required number of batches and units per batch is not fixed; it depends on the specific variability of the product and the sensitivity of the quality attributes being measured. The following tables summarize data-driven recommendations.

Table 1: Sample Size Scenarios Based on Variability and Expected Difference

| Inter-Batch Variability (%) | Intra-Batch Variability (%) | Expected T/R Difference (%) | Recommended Number of Batches | Recommended Units per Batch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<2.5) | Low (<2.5) | 0 (No difference) | 3 | 6 |

| Low to Moderate (<5) | Low to Moderate (<5) | 2.5 – 5 | 6 | 12 |

| Moderate to High (>10) | Moderate to High (>10) | 2.5 – 5 | >6 | >12 |

Table 2: Risk-Based Scenarios for Equivalence Acceptance Criteria

| Risk Level | Typical Acceptance Criteria Range (as % of tolerance) | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|

| High | 5 – 10% | Changes to drug product formulation, manufacturing process changes impacting Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs). |

| Medium | 11 – 25% | Changes in raw material suppliers, site transfers for non-sterile products. |

| Low | 26 – 50% | Changes with minimal perceived risk to safety/efficacy, such as certain analytical procedure updates. |

Experimental Protocols for Batch Comparison

Statistical Protocol for Equivalence Testing

The Two One-Sided T-test (TOST) is a widely accepted method for demonstrating comparability [2]. This protocol ensures that the difference between pre- and post-change batches is within a pre-specified "equivalence margin."

- Step 1 – Define the Equivalence Margin (∆): Set the upper and lower practical limits (UPL and LPL) based on a risk assessment, product knowledge, and clinical relevance. For a medium-risk attribute like pH with a specification of LSL=7 and USL=8, a common margin is ±0.15 (15% of the tolerance) [2].

- Step 2 – Formulate Hypotheses:

- H₀₁: Mean difference ≤ -∆ (Inferiority)

- H₀₂: Mean difference ≥ ∆ (Inferiority)

- Hₐ: -∆ < Mean difference < ∆ (Equivalence)

- Step 3 – Calculate Sample Size: Use a sample size calculator for a single mean (difference from standard). For alpha=0.1 (0.05 per one-sided test) and sufficient power (e.g., 80%), the minimum sample size can be determined. For the pH example, a minimum sample size of 13 is required, with 15 often selected [2].

- Step 4 – Execute the Experiment: Test the predetermined number of units from the selected pre- and post-change batches.

- Step 5 – Perform Statistical Analysis: Conduct two one-sided t-tests. If both tests yield p-values < 0.05, the null hypotheses are rejected, and equivalence is concluded [2].

Protocol for Extended Characterization and Forced Degradation

For biologics, a comprehensive analytical comparison is crucial. This involves head-to-head testing beyond routine release analytics [10].

- Extended Characterization: This provides an orthogonal, finer-level detail of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs). A typical testing panel for a monoclonal antibody includes:

- Primary Structure: Peptide mapping with LC-MS, Intact mass analysis (LC-ESI-TOF MS), Sequence variant analysis (SVA)

- Higher Order Structure: Size exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS), Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC)

- Purity and Impurities: Capillary electrophoresis (CE-SDS), Ion exchange chromatography (IEC)

- Potency: Cell-based bioassay [10]

- Forced Degradation Studies: These studies "pressure-test" the molecule to uncover potential differences in degradation pathways not seen in real-time stability. Standard stress conditions include:

- Thermal Stress: Incubation at elevated temperatures (e.g., 25°C, 40°C)

- pH Stress: Exposure to acidic and basic conditions

- Oxidative Stress: Exposure to chemicals like hydrogen peroxide

- Light Stress: As per ICH guidelines [10]

- The comparability of pre- and post-change batches is assessed by comparing the trendline slopes, bands, and peak patterns of the degradation profiles.

Diagram: Batch Comparability Study Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages in designing and executing a comparability study, from objective definition to final conclusion.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and solutions required for the analytical characterization of batches in a comparability study.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Extended Characterization and Forced Degradation Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Comparability Study |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard / Cell Bank | Serves as a benchmark for ensuring analytical method performance and provides a baseline for comparing pre- and post-change product quality attributes [10]. |

| Characterized Pre-Change Batches | Act as the reference material for head-to-head comparison. Batches should be representative and manufactured close in time to post-change batches to avoid age-related differences [10]. |

| Trypsin/Lys-C for Peptide Mapping | Enzymes used to digest the protein for detailed primary structure analysis and identification of post-translational modifications via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) [10]. |

| Stable Cell Line | Essential for conducting cell-based bioassays that measure the biological activity (potency) of the product, a critical quality attribute [10]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide Solution | A common oxidizing agent used in forced degradation studies to simulate oxidative stress and understand the molecule's degradation pathways [10]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol) with low UV absorbance and minimal contaminants are critical for sensitive analytical techniques like LC-MS to ensure accurate results [10]. |

A scientifically rigorous batch selection strategy is the cornerstone of a successful comparability study. The data and protocols presented demonstrate that the optimal number and representativeness of pre- and post-change batches are not one-size-fits-all but must be determined through a risk-based assessment of inter- and intra-batch variability. Employing a combination of rigorous statistical methods like equivalence testing and comprehensive analytical characterization provides the highest level of confidence for demonstrating comparability. By adhering to these structured approaches, drug developers can build robust data packages that satisfy regulatory requirements and ensure the continuous supply of high-quality medicines to patients.

In pharmaceutical development, the establishment of robust acceptance criteria is fundamental for demonstrating method comparability. While specification limits define the final acceptable quality attributes of a drug substance or product, acceptance criteria for analytical methods serve a different, equally critical purpose: they provide the documented evidence that an alternative analytical procedure is comparable to a standard or pharmacopoeial method [5]. This process is not merely a regulatory checkbox but a scientific exercise in risk management. The European Pharmacopoeia chapter 5.27, which addresses the "Comparability of alternative analytical procedures," underscores that the final responsibility for demonstrating comparability lies with the user and must be documented to the satisfaction of the competent authority [5]. This guide moves beyond basic specification limits to explore the strategic definition of acceptance criteria for both quantitative and qualitative methods, providing a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in method development, validation, and transfer activities.

Theoretical Foundations: Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research Paradigms

The approach to defining acceptance criteria is fundamentally shaped by the nature of the method—whether it is rooted in quantitative or qualitative research paradigms. Understanding this distinction is crucial for selecting appropriate comparison strategies.

- Quantitative Research deals with numbers and statistics, aiming to objectively measure variables and test hypotheses through structured, predetermined designs [26] [27]. It answers questions about "how many" or "how much" and seeks generalizable results. In an analytical context, this translates to methods that generate numerical data, such as assay potency or impurity content.

- Qualitative Research, in contrast, deals with words and meanings [26]. It is exploratory and seeks to understand concepts, thoughts, or experiences through a subjective, flexible lens [27] [28]. In a scientific context, this does not refer to subjective opinion but to methods that characterize qualities, such as the identity of a peak in a chromatogram, its morphology in microscopy, or descriptive physical attributes.

The choice between these paradigms dictates the entire approach to method comparability. Table 1 summarizes the core differences that influence how acceptance criteria are established.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Quantitative and Qualitative Research Approaches Influencing Acceptance Criteria

| Aspect | Quantitative Methods | Qualitative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | To test and confirm; to measure variables and test hypotheses [26] [27] | To explore and understand; to explore ideas, thoughts, and experiences [26] [27] |

| Nature of Data | Numerical, statistical [28] | Textual, descriptive, informational [28] |

| Research Approach | Deductive; used for testing relationships between variables [27] | Inductive; used for exploring concepts and experiences in more detail [26] |

| Sample Design | Larger sample sizes for statistical validity [29] | Smaller, focused samples for in-depth understanding [29] |

| Outcome | Produces objective, empirical data [27] | Produces rich, detailed insights into specific contexts [27] |

Defining Acceptance Criteria in a Regulatory Context

Acceptance criteria are specific, verifiable conditions that must be met to conclude that a product, process, or, in this context, an analytical method is acceptable [30] [31]. In the framework of method comparability, they are the predefined metrics that determine whether the results and performance of an alternative analytical procedure are comparable to those of a standard procedure [5]. Their primary function is to define the boundaries of success, mitigate risks of adopting a non-comparable method, and streamline testing by providing clear "pass/fail" standards [31]. According to regulatory guidance, the definition of these criteria should be based on the entirety of process knowledge and defined prior to running the comparability study [32] [5].

The Concept of Specification-Driven Acceptance Criteria

A modern, robust approach involves developing specification-driven acceptance criteria. This methodology leverages process knowledge and data to define intermediate acceptance criteria that are explicitly linked to the probability of meeting the final drug substance or product specification limits [32]. The novelty of this approach lies in basing acceptance criteria on pre-defined out-of-specification probabilities while accounting for manufacturing variability, moving beyond conventional statistical methods that merely describe historical data [32].

Comparative Analysis: Acceptance Criteria for Quantitative versus Qualitative Methods

The strategies for setting acceptance criteria differ significantly between quantitative and qualitative methods, reflecting their underlying paradigms.

Acceptance Criteria for Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods demand statistically derived, numerical acceptance criteria. The focus is on equivalence testing of Analytical Procedure Performance Characteristics (APPCs).

Common APPCs & Acceptance Strategies:

- Accuracy: Often evaluated through a comparison of mean results between the new and standard procedures. An equivalence approach is used, where the confidence interval of the difference must fall within predefined equivalence margins (e.g., ±1.5%) [5].

- Precision: Comparison of variance (e.g., repeatability, intermediate precision) using statistical tests like the F-test. Acceptance criteria may specify a maximum allowable ratio of variances.

- Specificity/Selectivity: Demonstration that the alternative method can discriminate the analyte in the presence of potential interferents, often by spiking studies.

Statistical Foundation: The preferred approach is equivalence testing (or "difference testing"), not just significance testing. For instance, one may decide that the confidence intervals of the mean results of two procedures differ by no more than a defined amount at an acceptable confidence level [5]. This is superior to conventional approaches like setting limits at ±3 standard deviations (3SD), which rewards poor process control and punishes good control by being solely dependent on observed variance [32].

Acceptance Criteria for Qualitative Methods

For qualitative methods, acceptance criteria are necessarily more descriptive and focus on the correct identification or characterization of attributes.

- Common APPCs & Acceptance Strategies:

- Specificity: The primary focus. Acceptance criteria define the required ability to discriminate between closely related entities (e.g., identification of a microorganism, confirmation of a polymorphic form). This is often assessed through a set of challenge samples, with criteria requiring 100% correct identification.

- Robustness: The ability of the method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. Acceptance is based on the method's consistent performance across these varied conditions.

- Comparability of "Fingerprints": For complex methods like spectroscopic identity tests, acceptance criteria may involve a direct, point-by-point comparison of spectra or chromatograms to a reference standard, requiring a match exceeding a predefined threshold (e.g., >99.0%).