Single-Cell Analysis Tools 2025: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This guide provides a definitive comparison of single-cell analysis tools, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Single-Cell Analysis Tools 2025: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This guide provides a definitive comparison of single-cell analysis tools, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of single-cell RNA sequencing, details the features and applications of leading bioinformatics platforms, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing analysis workflows. The content synthesizes the latest market trends, recent benchmarking studies, and emerging AI-powered tools to empower informed software selection, enhance data interpretation, and accelerate translational research in oncology, immunology, and neurology.

Understanding the Single-Cell Landscape: Technologies, Market Drivers, and Core Applications

The single-cell analysis market is experiencing robust global growth, driven by rising demand for personalized medicine and technological advancements in genomic tools. This market encompasses products and technologies that enable the study of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics at the level of individual cells, providing crucial insights into cellular heterogeneity that bulk analysis methods cannot offer [1] [2].

Table 1: Global Single-Cell Analysis Market Size and Growth Projections

| Market Size Year | Market Value (USD Billion) | Projection Year | Projected Value (USD Billion) | CAGR (%) | Source/Report Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 4.09 | 2034 | 18.68 | 16.40 | Precedence Research [1] |

| 2024 | 4.30 | 2034 | 20.00 | 16.70 | Global Market Insights [3] |

| 2024 | 3.81 | 2030 | 7.56 | 14.70 | MarketsandMarkets [4] |

| 2024 | 3.70 | 2029 | 6.90 | 13.60 | Research and Markets [5] |

| 2024 | 4.78 | 2032 | 15.26 | 15.60 | Data Bridge Market Research [6] |

Analysts estimate the market was valued between USD 3.7 billion and USD 4.9 billion in 2024 [5] [7]. The market is projected to reach between USD 6.9 billion by 2029 and USD 20 billion by 2034, reflecting a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 13.6% to 16.7% [5] [3].

Key Market Drivers and Trends

Several interrelated factors are propelling the expansion and transformation of the single-cell analysis landscape.

Primary Growth Drivers

- Rising Prevalence of Cancer and Chronic Diseases: Cancer research is the dominant application segment, accounting for approximately 30-32% of the market share [1] [2] [7]. Single-cell analysis is crucial for understanding tumor heterogeneity, identifying rare cancer stem cells, and monitoring treatment responses [4] [3].

- Technological Advancements: Continuous innovation in next-generation sequencing (NGS), microfluidics, and mass cytometry is enhancing the resolution, throughput, and accuracy of single-cell analysis [4] [7]. For instance, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reported a 45% increase in investments in single-cell technologies between 2021 and 2023 [3].

- Growing Focus on Personalized Medicine: The shift towards tailored treatments based on individual cellular profiles is a significant driver. The FDA approved 25% more personalized medicine treatments in 2023 compared to 2021, highlighting the critical role of single-cell technologies in modern medicine [3].

- Increased R&D Investment: Growing funding from governments and private organizations for life sciences research, particularly in genomics and biotechnology, is reducing financial barriers and accelerating innovation [4] [3].

Emerging Market Trends

- Multi-Omics Integration: There is a growing trend toward combining genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics at the single-cell level to gain a holistic view of cellular functions [2] [7] [3].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: This emerging trend combines single-cell sequencing with spatial context, allowing researchers to map gene expression within the native tissue architecture, which is invaluable for neuroscience and pathology [7].

- Automation and AI Integration: The adoption of automated workflows and AI-driven data analytics is streamlining single-cell experiments, improving reproducibility, and managing complex datasets [3] [8]. The National Science Foundation reported a 45% growth in investments for AI-driven biological data processing between 2021 and 2023 [3].

Market Segmentation and Regional Analysis

Market Segmentation

The single-cell analysis market can be broken down by product, application, technique, and end-user.

Table 2: Single-Cell Analysis Market Segmentation (2024)

| Segmentation Criteria | Leading Segment | Market Share (%) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Product | Consumables | 53% - 56.7% [1] [6] | Includes reagents, kits, beads; continuous demand due to repetitive use. |

| By Application | Cancer Research | 30.1% - 32% [1] [7] | Driven by need to understand tumor heterogeneity and develop targeted therapies. |

| By Technique | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) / Flow Cytometry | 31.5% (NGS) [6] / Largest share (Flow Cytometry) [4] [5] | NGS provides deep genetic insights; Flow Cytometry is widely adopted for rapid, multi-parameter cell analysis. |

| By End User | Academic & Research Laboratories | 70% - 72% [1] [7] | Fueled by government grants and fundamental biomedical research projects. |

Regional Landscape

- North America: The dominant region, accounting for approximately 37-45% of the global market share [1] [6]. This leadership is attributed to strong biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors, robust research funding, and the presence of key market players [1] [5].

- Asia-Pacific: This is the fastest-growing region, expected to register the highest CAGR during the forecast period. Growth is driven by increasing healthcare investments, expanding biotechnology sectors in China and India, and a rise in outsourced research projects [1] [4] [6].

- Europe: Holds a significant market share, supported by a strong biomedical research ecosystem and funding initiatives such as the EU Horizon programs [4].

Competitive Landscape and Recent Developments

The single-cell analysis market features a competitive landscape with several established players and innovative companies.

Table 3: Key Players and Strategic Developments in the Single-Cell Analysis Market

| Company | Notable Products/Initiatives | Recent Strategic Developments |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics | Chromium Single Cell Platform, GEM-X technology [4] | Partnership with Hamilton Company (Nov 2024) to develop automated, high-throughput library preparation solutions [4]. |

| Illumina, Inc. | Integrated single-cell RNA sequencing workflows [4] | Acquisition of Fluent BioSciences (Jul 2023) to enhance single-cell analysis capabilities [9]. |

| BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company) | Flow cytometers, OMICS reagent kits [4] | Launched BD OMICS-One XT WTA Assay (Oct 2024), a robotics-compatible kit for high-throughput studies [4]. |

| Thermo Fisher Scientific | Comprehensive portfolio of instruments and consumables [5] | A leading player with a strong global distribution network and integrated multi-omics solutions [3]. |

| Bio-Rad Laboratories | ddSEQ Single-Cell 3' RNA-Seq Kit [9] | Launched a Single-Cell 3' RNA-Seq Kit for high-throughput gene expression analysis (Jun 2024) [9]. |

Leading players collectively hold a significant market share, with reports indicating that Thermo Fisher Scientific, Illumina, Merck KGaA, BD, and 10x Genomics together accounted for approximately 67% of the market in 2024 [3]. Common strategies include product innovation, strategic partnerships, and acquisitions to expand technological capabilities and market reach [2] [4].

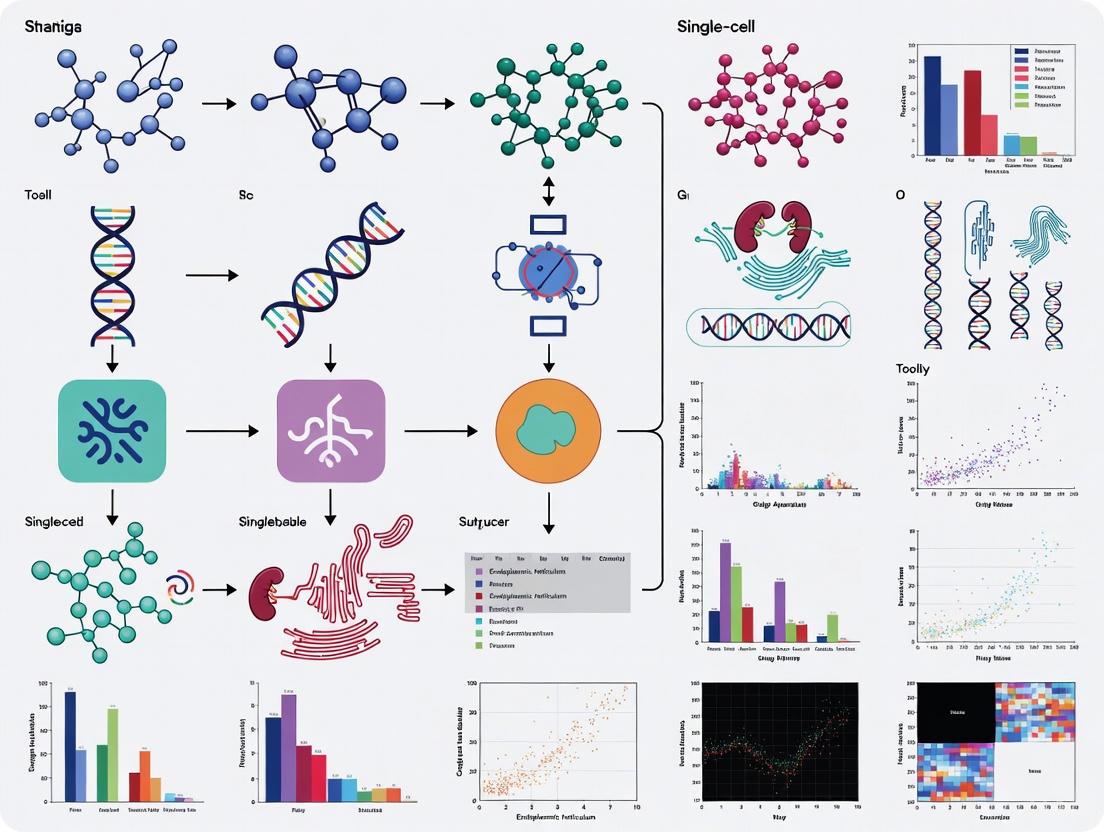

Experimental Workflow in Single-Cell Analysis

A typical single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) experiment involves a multi-step workflow to isolate, prepare, and analyze individual cells. The following diagram illustrates the key stages from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: scRNA-seq

The workflow for a standard single-cell RNA sequencing experiment can be broken down into the following critical steps [1] [4]:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: A tissue sample of interest is collected and dissociated into a single-cell suspension using enzymatic and mechanical methods. The goal is to maximize cell yield while preserving RNA integrity.

- Cell Viability Assessment: The cell suspension is assessed for viability and concentration. Dead cells can release RNA and contaminate the data, so viability is typically required to be >80% for optimal results.

- Single-Cell Isolation: This is a critical step where individual cells are partitioned. Modern platforms often use microfluidic devices (e.g., from 10x Genomics) to encapsulate single cells into nanoliter-sized droplets along with barcoded beads. Each bead is coated with oligonucleotides containing a unique Cell Barcode (to tag all mRNA from a single cell) and a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) (to count individual mRNA molecules and correct for amplification bias).

- Cell Lysis and Reverse Transcription: Within each droplet or well, the cell is lysed to release its mRNA. The poly-A tails of mRNA molecules hybridize to the poly-T sequences on the barcoded beads, and reverse transcription occurs, converting mRNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) that now carries the cell-specific barcode and UMI.

- cDNA Amplification and Library Preparation: The barcoded cDNA from all cells is pooled and amplified via PCR to generate sufficient material for sequencing. During library preparation, sequencing adapters are added to the cDNA fragments.

- Next-Generation Sequencing: The final library is sequenced on a high-throughput platform (e.g., from Illumina), generating millions of short sequencing reads.

- Bioinformatics Analysis: The raw sequencing data is processed through a computational pipeline. This involves:

- Demultiplexing: Assigning reads to individual samples based on their barcodes.

- Alignment: Mapping reads to a reference genome.

- Quantification: Counting the number of UMIs per gene per cell to create a digital gene expression matrix.

- Downstream Analysis: Using tools for quality control, normalization, dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA, UMAP), cell clustering, and differential gene expression analysis to extract biological insights.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful single-cell experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and consumables. The following table details key components used in a typical scRNA-seq workflow.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq

| Reagent / Consumable | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Cell Suspension Buffer | Maintains cell viability and prevents clumping in a single-cell suspension prior to loading onto the instrument [4]. |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Microbeads containing millions of unique oligonucleotide barcodes. Each bead is co-partitioned with a single cell to uniquely tag all RNA from that cell [2]. |

| Partitioning Oil | Used in droplet-based systems to create stable, individual water-in-oil emulsions where each droplet acts as a separate reaction vessel [2]. |

| Reverse Transcription (RT) Reagents | Enzyme and buffers to convert the captured mRNA into stable, barcoded cDNA within each droplet or well [4]. |

| PCR Master Mix | Enzymes, nucleotides, and buffers for the amplification of barcoded cDNA to generate enough material for library construction [4]. |

| Library Preparation Kit | Reagents for fragmenting, sizing selecting, and adding platform-specific sequencing adapters to the amplified cDNA [4] [9]. |

| Solid Tissue Dissociation Kit | Enzymatic cocktails (e.g., collagenase, trypsin) for breaking down solid tissues into a viable single-cell suspension without damaging cell surface markers or RNA [4]. |

| Viability Stain | A dye (e.g., propidium iodide) to distinguish and filter out dead cells during sample quality control, which is critical for data quality [4]. |

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by allowing researchers to investigate gene expression at the level of individual cells rather than population averages [10]. This technology reveals the extraordinary transcriptional diversity within tumors and complex tissues, enabling the identification of rare cell types, distinct cell states, and subtle transcriptional differences that are obscured in bulk RNA sequencing approaches [11] [12]. The core principle of scRNA-seq involves isolating single cells, typically through encapsulation or flow cytometry, followed by RNA amplification and sequencing to generate gene expression profiles for thousands of individual cells simultaneously [12].

The field has evolved from classic bulk RNA sequencing to popular single-cell RNA sequencing and now to newly emerged spatial RNA sequencing, which represents the next generation of RNA sequencing by adding spatial context to transcriptional data [11]. This progression has been driven by advancements in microfluidics, barcoding technologies, and computational分析方法. Commercial integrated systems like 10x Genomics Chromium have triggered rapid adoption of this technology by providing complete solutions for analyzing up to 20,000 individual cells in a single assay [11]. As the market continues to grow—projected to reach $9.1 billion by 2029 with a 17.6% CAGR—understanding the core technologies and protocols becomes increasingly important for researchers and drug development professionals [13].

Comparative Analysis of scRNA-seq Experimental Protocols

Key Performance Metrics and Technical Parameters

Systematic comparisons of scRNA-seq protocols have revealed significant differences in their performance characteristics, requiring researchers to make informed choices based on their specific experimental needs [14]. The major technical parameters that distinguish various protocols include cell isolation techniques, transcript coverage, throughput, strand specificity, multiplexing capability, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), cost, and technical complexity [15]. These parameters directly impact critical performance metrics such as the number of genes detected per cell, quantification accuracy, technical noise, and cost efficiency [14].

Protocols differ fundamentally in their molecular approaches. Some methods like Smart-seq2 provide full-length transcript coverage, while others such as CEL-seq2, Drop-seq, MARS-seq, and SCRB-seq focus on 3' or 5' ends but offer more quantitative accuracy through UMIs that reduce amplification noise [14]. The throughput capacity ranges from low-throughput plate-based methods processing 1-100 cells to high-throughput droplet-based systems capable of analyzing >10,000 cells [15]. These technical considerations directly influence protocol selection for specific research scenarios.

Comprehensive Protocol Comparison Table

Table 1: Comparative analysis of major scRNA-seq protocols and their performance characteristics

| Protocol | Released Year | Method Type | Throughput | Cost per Cell (USD) | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Average Genes Detected per Cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRT-seq | 2011 | Plate-based | Low | ~$2.00 | 5' | No | 1,000-8,000 |

| Smart-seq2 | 2014 | Plate-based | Low | $1.50-$2.50 | Full-length | No | 6,500-10,000 |

| CEL-seq2 | 2016 | Plate-based/Microfluidics | Medium | $0.30-$0.50 | 3' | Yes (6bp) | 5,000-7,000 |

| Drop-seq | 2015 | Droplet-based | High | $0.10-$0.20 | 3' | Yes (8bp) | 2,000-6,000 |

| 10X Chromium V2 | 2017 | Droplet-based | High | ~$0.50 | 3' | Yes (10bp) | 4,000-7,000 |

| MARS-seq | 2014 | Plate-based | High | $1.30 | 3' | Yes (10bp) | 500-5,000 |

| SCRB-seq | 2014 | Plate-based | Low | $1.70 | 3' | Yes (10bp) | 5,000-9,000 |

| MATQ-seq | 2017 | Plate-based | Medium | $0.40-$0.60 | Full-length | Yes | 8,000-14,000 |

| Quartz-seq2 | 2018 | Plate-based | Medium | $0.40-$1.08 | 3' | Yes (8bp) | 5,500-8,000 |

| Smart-seq3 | 2020 | Plate-based | Low | $0.57-$1.14 | Full-length | Yes (8bp) | 9,000-12,000 |

Power Analysis and Cost-Effectiveness by Application Scenario

Comparative analyses reveal that protocol selection involves important trade-offs between gene detection sensitivity, cell throughput, and cost efficiency [14]. Power simulations at different sequencing depths demonstrate that Drop-seq is more cost-efficient for transcriptome quantification of large numbers of cells, while MARS-seq, SCRB-seq, and Smart-seq2 are more efficient when analyzing fewer cells where deeper genomic coverage is required [14].

The selection criteria should align with specific research objectives:

- For high-throughput genomics-focused labs: 10x Genomics remains a top choice due to its scalability and balanced performance [16].

- For comprehensive transcriptome characterization: Smart-seq2 and Smart-seq3 detect the most genes per cell, making them ideal for isoform-level analysis [14].

- For quantitative accuracy: Protocols employing UMIs (CEL-seq2, Drop-seq, MARS-seq, SCRB-seq) quantify mRNA levels with less amplification noise [14].

- For budget-constrained studies: Drop-seq and combinatorial indexing methods (sci-RNA-seq, Split-seq) offer the lowest cost per cell at $0.01-$0.20 [15].

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Integration Platforms

Commercial Multi-Omics Solutions

The single-cell omics landscape has expanded beyond transcriptomics to include integrated multi-omics approaches that simultaneously measure multiple molecular layers from the same cells [16]. This evolution enables researchers to decode cellular complexity at unprecedented resolution by combining genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from individual cells [16]. Leading companies have developed specialized platforms tailored to different research applications, with 10x Genomics, Thermo Fisher, and Illumina currently leading the market that is projected to reach $9.1 billion by 2029 [13].

Vendor selection requires careful consideration of several factors, including vendor support, ecosystem maturity, workflow integration, analytical capabilities, and scalability [16]. Different buyers have distinct needs that align with specific platform strengths. The competitive environment includes both established players and emerging specialists, with market consolidation expected through strategic acquisitions and partnerships [16] [13].

Table 2: Comparison of leading single-cell multi-omics platforms and their applications

| Company/Platform | Core Technology | Strengths | Ideal Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics | Microfluidic droplet partitioning | High scalability, comprehensive solution | High-throughput genomics-focused labs, drug target discovery |

| Mission Bio Tapestri | Targeted DNA and multi-omics | Rare mutation identification | Cancer research, tumor heterogeneity studies |

| BD Rhapsody | Flexible workflows, customizable | Workflow adaptability | Immunology labs, customized assay designs |

| Ultivue | Multiplexed imaging | Spatial context preservation | Spatial analysis teams, tumor microenvironment mapping |

| Parse Biosciences | Scalable, cost-effective | Accessibility for smaller budgets | Smaller or emerging labs, large-scale studies |

Methodological Framework for Multi-Omics Integration

The integration of multiple omics modalities involves sophisticated computational and experimental approaches [17]. A typical multi-omics integration workflow includes: (1) sample preparation with multi-modal barcoding, (2) library preparation for each molecular modality, (3) sequencing and data generation, (4) quality control and preprocessing, (5) modality-specific analysis, (6) cross-modality integration, and (7) biological interpretation.

Emerging AI and machine learning approaches are addressing the limitations of traditional, manually defined analysis workflows [17]. LLM-based agents show particular promise for adaptive planning, executable code generation, traceable decisions, and real-time knowledge fusion in multi-omics data analysis [17]. Benchmarking studies indicate that multi-agent frameworks significantly enhance collaboration and execution efficiency over single-agent approaches through specialized role division, with Grok-3-beta currently achieving state-of-the-art performance among tested agent frameworks [17].

Diagram 1: Single-cell multi-omics integration workflow

Computational Analysis Tools and Reproducibility

Comparative Analysis of Seurat and Scanpy

The computational analysis of scRNA-seq data presents significant challenges in reproducibility and consistency across tools [10]. Seurat (R-based) and Scanpy (Python-based) represent the two most widely used packages for scRNA-seq analysis, and while generally thought to implement individual steps similarly, detailed investigations reveal considerable differences in their outputs [10]. These differences emerge across multiple analysis stages including filtering, highly variable gene selection, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and differential expression analysis.

Substantial variability occurs even when using identical input data and default settings [10]. The selection of highly variable genes shows particularly low agreement with a Jaccard index of 0.22, indicating that only a small fraction of selected genes overlap between the tools. Differential expression analysis reveals a Jaccard index of 0.62, with Seurat identifying approximately 50% more significant marker genes than Scanpy due to differing default settings for statistical corrections and filtering methods [10]. These discrepancies highlight the substantial impact of software choice on biological interpretation.

Impact of Software Versions and Random Seeds

Beyond differences between software packages, version changes within the same tool can significantly impact results [10]. Comparisons between Seurat v4 and v5 revealed considerable differences in significant marker genes, primarily due to adjustments in how log-fold changes are calculated. The impact of these software-related differences is substantial—approximately equivalent to the variability introduced by sequencing less than 5% of the reads or analyzing less than 20% of the cell population [10].

The influence of random seeds on stochastic processes represents another consideration for reproducibility. While clustering and UMAP visualization involve randomness, analysis shows that variability introduced by different random seeds is much smaller than differences between Seurat and Scanpy [10]. This underscores the importance of maintaining consistent software versions throughout a project and thoroughly documenting parameter choices to ensure reproducible results.

Best Practices for Computational Analysis

To address these challenges, researchers should adopt several best practices:

- Maintain consistent software versions throughout a project

- Document all parameters and analysis choices in detail

- Perform sensitivity analyses to understand how tool selection affects conclusions

- Utilize benchmarking frameworks to validate results across multiple tools

- Follow established community standards and workflows

The scRNA-tools database currently catalogs over 1,000 tools for single-cell RNA-seq analysis, reflecting the rapid evolution and specialization in this field [18]. Comprehensive resources like the Single-cell Best Practices book provide guidance for navigating this complex landscape across various analysis modalities including transcriptomics, chromatin accessibility, surface protein quantification, and spatial transcriptomics [18].

Specialized Applications and Emerging Technologies

Single-Cell MicroRNA Sequencing

Single-cell microRNA (miRNA) sequencing presents unique technical challenges compared to standard scRNA-seq, requiring specialized protocols and considerations [19]. Comprehensive evaluations of 19 miRNA-seq protocol variants revealed that performance strongly depends on the applied method, with significant variations in adapter dimer formation, reads mapping to miRNA, detection sensitivity, and reproducibility [19]. The best-performing protocols detected a median of 68 miRNAs in circulating tumor cells, with 10 miRNAs being expressed in 90% of tested cells.

Critical technical considerations for single-cell miRNA sequencing include:

- Adapter design: Significantly impacts ligation efficiency and dimer formation

- Input requirements: Extreme low input increases bias and variability

- UMI incorporation: Essential for accurate quantification

- Protocol selection: Markedly affects detection sensitivity and reproducibility

Successful application to clinical samples demonstrates the potential of single-cell miRNA sequencing for identifying tissue of origin and cancer-related categories in circulating tumor cells [19]. The identification of non-annotated candidate miRNAs further underscores the discovery potential of this emerging technology.

Spatial Transcriptomics and Multi-Omics Integration

Spatial transcriptomics represents the next generation of RNA sequencing by preserving spatial context while capturing transcriptome-wide information [11]. This technology enables researchers to dissect RNA activities within native tissue architecture, providing critical insights into cellular organization and communication in tissues and tumors [11]. Platforms like Ultivue's multiplexed imaging allow comprehensive mapping of tumor microenvironments, confirming spatial relationships with histology [16].

The integration of spatial information with single-cell multi-omics data creates powerful opportunities to understand tissue organization and cell-cell communication [11]. This is particularly valuable in oncology for characterizing the tumor microenvironment, which comprises diverse cell types including cancer cells, immune cells, and stromal cells [11]. Understanding the spatial relationships and interactions between these cells provides crucial insights into cancer progression, metastasis, and treatment response.

Diagram 2: Evolution of RNA sequencing technologies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and their functions in single-cell omics

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Barcoded Gel Beads | Cell-specific barcoding | Enables multiplexing of thousands of cells with unique identifiers |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular tagging | Distinguishes biological duplicates from technical amplification duplicates |

| Reverse Transcription Mixes | cDNA synthesis | Converts RNA to stable cDNA for amplification and sequencing |

| Partitioning Reagents | Microdroplet generation | Creates nanoliter-scale reactions for single-cell encapsulation |

| Spike-in RNAs | Quality control and normalization | External standards for quantification accuracy assessment |

| Library Preparation Kits | Sequencing library construction | Prepares barcoded cDNA for next-generation sequencing |

| Cell Viability Reagents | Live/dead cell discrimination | Ensures high-quality input material by removing compromised cells |

The landscape of single-cell technologies has evolved dramatically from initial scRNA-seq protocols to sophisticated multi-omics integration platforms. This comparative analysis demonstrates that protocol selection involves significant trade-offs between throughput, sensitivity, cost, and application specificity. Researchers must carefully match technological capabilities to biological questions, whether prioritizing high cell numbers for population studies or deep molecular characterization for rare cell analysis.

The field continues to advance rapidly, with emerging trends including spatial multi-omics, AI-enhanced analysis, and automated workflow solutions [16] [17]. As single-cell technologies progress toward clinical applications, emphasis on validation, standardization, and regulatory compliance will increase [16]. Future developments will likely focus on improving accessibility through flexible pricing models, enhancing integration capabilities across omics modalities, and developing more sophisticated computational methods for extracting biological insights from these complex datasets.

For researchers and drug development professionals, maintaining awareness of both the technical considerations outlined in this guide and the rapidly evolving landscape will be essential for designing effective studies and translating single-cell insights into meaningful biological and clinical advances.

Single-cell analysis has revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the detailed examination of cellular heterogeneity, function, and molecular mechanisms at an unprecedented resolution. This guide provides an objective comparison of how these tools are applied across three dominant fields—oncology, immunology, and neurology—by detailing specific experimental protocols, key findings, and the performance of various technological solutions. The content is framed within a broader thesis on single-cell analysis tool comparison to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing these technologies.

Single-cell analysis technologies represent a paradigm shift from traditional bulk sequencing methods, which average signals across thousands of cells, thereby obscuring crucial cellular heterogeneity. The global single-cell analysis market, valued at USD 3.90–4.78 billion in 2024, is projected to grow at a CAGR of 13.61%–15.6% to reach USD 12.29–15.26 billion by 2032, underscoring its rapid adoption and transformative potential across biomedical research [6] [20].

The technology's power lies in its ability to resolve the diversity of cellular populations and states within complex tissues. This is particularly critical in oncology, immunology, and neurology, where cellular heterogeneity drives disease pathogenesis, treatment response, and resistance mechanisms. In oncology, single-cell analysis deciphers the complex tumor ecosystem; in immunology, it unravels the diversity of immune cell states and receptor specificities; and in neurology, it maps the extraordinary cellular complexity of the brain [21] [22] [23]. The following sections provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of experimental approaches, tool performance, and key insights across these three dominant application areas.

Field-Specific Workflows and Analytical Pipelines

The application of single-cell technologies requires field-specific adjustments to experimental workflows and bioinformatic pipelines to address unique biological questions and technical challenges.

Comparative Workflow Table

The table below summarizes the core objectives and analytical foci specific to each research field.

| Field | Core Objective | Key Analytical Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Decipher tumor heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment (TME) for precision therapy. | Cell subpopulations, copy number variations, TME cell-cell communication, metastatic clones, drug resistance mechanisms. |

| Immunology | Profile immune repertoire and resolve complex immune gene families. | Immune cell states, clonotype tracking (TCR/BCR), antigen specificity, immune activation/exhaustion pathways, HLA/MHC genotyping. |

| Neurology | Map the brain's cellular diversity and understand molecular basis of cognition/ disease. | Neural cell type classification, transcriptional states in development & disease, neural circuit mapping, synaptic signaling. |

Specialized Bioinformatics Pipelines

Standard single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) pipelines, which align reads to a single reference genome, are often insufficient for immunology research. Complex immune gene families like the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) and Killer-Immunoglobulin-like Receptors (KIRs) exhibit high polymorphism and are poorly represented in standard references, leading to systematically missing or inaccurate data [24] [25].

- Experimental Protocol: Supplemental Immune-Focused Alignment

- Tool: Nimble, a lightweight pseudoalignment tool.

- Method: As a supplement to standard pipelines (e.g., CellRanger), Nimble processes scRNA-seq data using one or more customizable gene spaces. This allows for tailored scoring criteria specific to the biology of immune genes.

- Workflow:

- Generate standard scRNA-seq count matrix using a primary pipeline.

- Create custom reference spaces (e.g., containing all known MHC/HLA alleles or viral genomes).

- Execute Nimble with tailored alignment thresholds for each custom reference.

- Merge the supplemental count matrix (from Nimble) with the standard matrix for a complete dataset.

- Outcome: This protocol recovers data missed by standard tools, enabling accurate immune genotyping, identification of allele-specific MHC regulation, and detection of viral RNA, thereby revealing cellular subsets otherwise invisible [24].

The following diagram illustrates this supplemental bioinformatics workflow.

Quantitative Data and Tool Performance Comparison

The impact of single-cell analysis varies across disciplines, reflected in market data, research output, and the specific tools that dominate each field.

Market Size and Research Output by Field

| Field | Market Share/Dominance | Key Growth Driver (CAGR) | Research Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Largest application segment (33.2% share) [20]. | Highest growth in applications (CAGR 19.87%) [20]. | >55% of global SCA studies focus on oncology/immunology [20]. |

| Immunology | Integral part of the dominant oncology segment and a major standalone field. | Driven by immuno-oncology and infectious disease research. | Over 4,856 publications on single-cell analysis in tumor immunotherapy (1998-2025) [23]. |

| Neurology | Significant and growing application area. | Driven by brain atlas initiatives and neurodegenerative disease research. | Rapidly expanding with initiatives like the Human Cell Atlas [22]. |

Dominant Techniques and Platform Performance

The performance of single-cell analysis is highly dependent on the chosen technology. The table below compares key platforms and their efficacy across applications.

| Technology/Platform | Primary Field | Key Performance Metric | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics | Cross-disciplinary | High-throughput cell capture, reduced per-sample cost [20]. | Integrated solutions for RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and spatial genomics. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Cross-disciplinary | Dominates technique segment (31.5% share) [6]. | Provides in-depth gene expression and mutation analysis. |

| Neuropixels Probes | Neurology | Records hundreds of neurons simultaneously in awake humans [22]. | Unprecedented resolution for linking human neural activity to behavior. |

| Nimble Pipeline | Immunology | Recovers missing MHC/KIR data; identifies allele-specific regulation [24]. | Solves alignment issues in polymorphic immune gene families. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Oncology, Neurology | Maps gene expression within tissue architecture [21]. | Preserves critical spatial context of cells in the TME and brain. |

Key Experimental Findings and Clinical Impact

Single-cell analysis has yielded profound insights into cellular mechanisms and is increasingly informing clinical decision-making.

Insights from Single-Cell Profiling

- Oncology: scRNA-seq of melanoma patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors revealed a cancer-cell-specific gene program associated with T-cell exclusion and therapy resistance. This program involved upregulation of genes related to antigen presentation, IFN-γ signaling, and immune cell migration, providing a potential biomarker for treatment failure [21].

- Immunology: The application of the Nimble pipeline to scRNA-seq data from rhesus macaques identified killer-immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) expression specific to tissue-resident memory T cells and demonstrated allele-specific regulation of MHC-I following Mycobacterium tuberculosis stimulation. This finding, missed by standard pipelines, highlights a novel layer of immune regulation [24] [25].

- Neurology: Single-cell pan-omics (transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics) applied to human brain tissue allows for the detailed classification of neural cell types and states. This approach is crucial for understanding neural development, neurodegenerative disorders, and the molecular dynamics underlying cognitive functions by identifying rare cell populations and transitional states [22] [26].

Translation to Precision Medicine

The transition from research to clinical application is most advanced in oncology.

- AI-Driven Diagnostics: Platforms like 1Cell.Ai integrate single-cell multi-omics data with AI to provide real-time, precision insights for oncologists. Their tests (e.g., OncoIndx, OncoHRD) offer actionable information for targeted therapy, immunotherapy selection, and resistance detection, reportedly achieving >90% accuracy in predicting therapy response [27].

- Resistance Monitoring: Case studies demonstrate the clinical utility of single-cell analysis. In one example, a liquid biopsy test for longitudinal monitoring tracked treatment response in a patient with multi-treated, ER+ metastatic breast cancer, identifying an ESR1 mutation as a key mediator of resistance, thus guiding subsequent therapy choices [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful single-cell experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The consumables segment dominates the market, holding a 54.2%-56.7% share due to their recurrent use [6] [20].

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation Kits | FACS, MACS, microfluidic chips, droplet-based systems (e.g., from 10x Genomics) | High-throughput isolation and encapsulation of single cells from tissue or blood samples. |

| Library Prep Kits | Assay kits for scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, CITE-seq (e.g., from Thermo Fisher, Illumina) | Barcoding, reverse transcription, and amplification of cellular molecules (RNA, DNA) for sequencing. |

| Key Consumables | Microplates, reagents, assay beads, buffers, culture dishes [6]. | Essential components used repeatedly across experiments for cell handling, lysis, and reactions. |

| Instrumentation | Flow cytometers, NGS systems (Illumina), PCR instruments, microscopes [6]. | Platform-specific instruments for cell analysis, sorting, and sequencing library quantification. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CellRanger, Seurat, Scanpy, Nimble [24] [21]. | Software for data processing, alignment, quality control, visualization, and differential expression. |

Integrated Signaling Pathways in Oncology and Neurology

Single-cell technologies have elucidated key signaling pathways that drive disease processes. Two major pathways are highlighted below.

T-cell Exhaustion Pathway in Cancer

In the tumor microenvironment, chronic antigen exposure leads to T-cell exhaustion, a state of dysfunction that limits immunotherapy efficacy. Key features include sustained expression of inhibitory receptors (e.g., PD-1), epigenetic remodeling, and metabolic alterations [21] [23].

Neuro-Immune Signaling Axis

The brain is not immunologically privileged. Single-cell studies reveal complex communication between neural and immune cells, which is perturbed in neurodegenerative diseases and influenced by environmental exposures [22] [26].

The single-cell analysis market is characterized by dynamic growth, driven by technological advancements and increasing demand in precision medicine. The market segmentation into consumables and instruments reveals distinct trends, with consumables consistently leading in revenue share while instruments exhibit robust growth due to technological innovation.

Table 1: Single-Cell Analysis Market Overview

| Metric | Figures | Source/Time Frame |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2024/2025) | USD 4.78 billion (2024) [6] / USD 4.2 billion (2025) [28] | Base Year 2024/2025 |

| Projected Market Size (2034) | USD 10.9 billion [28] | Forecast to 2034 |

| Projected Market Size (2032) | USD 15.26 billion [6] | Forecast to 2032 |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 11.2% [28] to 15.6% [6] | 2025-2034 / 2024-2032 |

Table 2: Consumables vs. Instruments Market Share

| Segment | Market Share | Key Characteristics & Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Consumables | 54.8% of revenue share (2023) [2]56.7% share (2025 projection) [6] | Includes reagents, assay kits, and microplates. Dominance is driven by continuous, recurring usage in research and diagnostics [2]. |

| Instruments | Significant growth trajectory [2] | Includes next-generation sequencing (NGS) systems, flow cytometers, and PCR devices. Growth is fueled by advancements in automation, AI integration, and high-throughput capabilities [2] [28]. |

Key Market Players and Product Profiles

The competitive landscape features established life science giants and specialized technology companies, each with distinct product strategies across consumables and instruments.

Table 3: Key Players and Their Primary Product Segments

| Company | Strength in Consumables | Strength in Instruments | Notable Platforms/Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics, Inc. | Assay kits for gene expression, immune profiling [29] | Chromium Controller (microfluidics-based) [30] [29] | Chromium Single Cell product suite [2] [29] |

| Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. | Reagents and assay kits [2] | Instruments for droplet-based single-cell analysis [2] | — |

| Illumina, Inc. | Sequencing reagents and kits [28] | Next-generation sequencing (NGS) systems [2] [6] | — |

| Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. | Comprehensive portfolio of reagents and kits [2] [28] | PCR instruments, spectrophotom | — |

| BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company) | Assay kits for single-cell multiomics [28] | BD Rhapsody scanner and analyzer systems [29] | BD Rhapsody platform [29] |

| Fluidigm Corporation (Standard BioTools Inc.) | Assay panels | Integrated fluidic circuit (IFC) systems (e.g., C1 system) [31] | — |

| Parse Biosciences | Evercode combinatorial barcoding kits [29] | Instrument-free platform [29] | Evercode technology [29] |

| Scale Biosciences | Scale Bio single-cell RNA sequencing kits [29] | Instrument-free platform [29] | Split-pool combinatorial barcoding [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Independent comparative studies provide critical data on the performance of different single-cell analysis platforms, informing tool selection based on specific research needs.

Multi-Platform scRNA-seq Comparison Protocol

A seminal study compared several scRNA-seq platforms using SUM149PT cells (a human breast cancer cell line) treated with Trichostatin A (TSA) versus untreated controls [31].

Experimental Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: SUM149PT cells were cultured and treated with 10 nM TSA or a DMSO vehicle control for 48 hours. Cells were harvested and shipped to different laboratories for analysis to minimize technical variability [31].

- Platforms Tested: The study included data from:

- Fluidigm C1 (96 and HT): Employs integrated microfluidic chips for cell capture, on-chip lysis, and cDNA synthesis using the SMARTer Ultra Low RNA kit [31].

- WaferGen iCell8: A nanowell-based system where cells are dispensed into 5184-nanowell chips, followed by imaging and processing [31].

- 10x Genomics Chromium Controller: A droplet-based microfluidics system that partitions single cells with barcoded gel beads for 3' or 5' tag-based sequencing [31] [29].

- Illumina/BioRad ddSEQ: Uses disposable microfluidic cartridges to co-encapsulate single cells and barcodes into droplets [31].

- Data Analysis: Bulk RNA-seq data from the same cell line served as a reference for evaluating platform performance on sensitivity, accuracy, and ability to detect TSA-induced transcriptional changes [31].

Key Findings: The study concluded that platform choice involves trade-offs. Droplet-based methods (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) offered superior throughput, capable of processing thousands to tens of thousands of cells per run. In contrast, plate-based and microfluidic systems (e.g., Fluidigm C1, WaferGen iCell8) provided opportunities for full-length transcript analysis and allowed for quality control via visual confirmation of cell viability after capture [31].

Instrument-Based vs. Instrument-Free Workflows

Beyond traditional instruments, new instrument-free methods represent a significant evolution in experimental workflow, leveraging combinatorial barcoding.

Instrument-Based Workflow (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium):

- Principle: Cells are partitioned into nanoliter-scale droplets using a specialized microfluidic chip ("GEM" chip) within the Chromium Controller. Each droplet contains a single cell and a barcoded gel bead [30] [29].

- Process: Within each droplet, cell lysis occurs, and mRNA transcripts are barcoded with a unique cell-specific identifier. The barcoded cDNA from all droplets is then pooled for library preparation and sequencing [29].

- Advantages: High-throughput, standardized and automated workflow, and rapid turnaround time (partitioning takes minutes) [30] [29].

Instrument-Based scRNA-seq Workflow

Instrument-Free Workflow (e.g., Parse Biosciences, Scale Biosciences):

- Principle: Utilizes split-pool combinatorial barcoding. Fixed and permeabilized cells undergo multiple rounds of labeling with different barcode sets in solution [29].

- Process: Cells are first distributed into a multi-well plate. In each round of barcoding, a unique barcode is added to all RNA molecules in a well. Cells are then pooled and randomly re-distributed into a new plate for the next barcoding round. The unique combination of barcodes from multiple rounds assigns a cellular origin to each RNA molecule post-sequencing [29].

- Advantages: Eliminates capital cost for instruments, provides high scalability to millions of cells, and offers flexibility for labs without access to specialized equipment [29].

Instrument-Free scRNA-seq Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Proteomics

Moving beyond transcriptomics, single-cell proteomics (scMS) requires specialized reagents to handle ultra-low analyte amounts.

Table 4: Key Reagents for Single-Cell Mass Spectrometry (scMS)

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| TMTPro 16-plex Kit | Isobaric labeling tags for multiplexing; allows pooling of 16 samples for simultaneous MS analysis [32]. | Enables quantification of ~1000 proteins/cell. A "carrier" channel (e.g., 200-cell equivalent) boosts signal for identification [32]. |

| Trifluoroethanol (TFE) Lysis Buffer | Chaotropic cell lysis reagent [32]. | More efficient lysis and higher peptide yields compared to pure water, increasing protein identifications [32]. |

| SMARTer Ultra Low RNA Kit | For single-cell cDNA synthesis and pre-amplification in plate-based protocols [31]. | Used in Fluidigm C1 and other full-transcript protocols for whole transcriptome analysis [31]. |

| Single-Cell Multiplexing Kits | Assay kits for gene expression (e.g., 10x Genomics 3' v4, Parse Biosciences Evercode) [28] [29]. | Core consumables defining the readout (3', 5', or whole transcriptome) for single-cell RNA sequencing. |

The single-cell analysis market represents a transformative frontier in biological research and clinical diagnostics, enabling unprecedented resolution in understanding cellular heterogeneity. This field has evolved from bulk analysis techniques to sophisticated platforms that can characterize individual cells, revealing differences that were previously obscured in population-averaged measurements. The global market for these technologies is experiencing robust growth, valued between $3.55 billion to $4.90 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $7.56 billion to $21.97 billion by 2030-2035, with compound annual growth rates (CAGR) ranging from 14.7% to 16.7% [3] [7] [4]. This growth trajectory underscores the critical importance of single-cell technologies across basic research, drug discovery, and clinical diagnostics.

Regional adoption patterns reveal a dynamic interplay between established technological leaders and rapidly emerging markets. North America currently dominates the global landscape, while the Asia-Pacific region demonstrates the most accelerated growth potential. Understanding the drivers, constraints, and future outlook for these regions provides valuable insights for researchers, investors, and policymakers navigating this complex market. This analysis examines the quantitative metrics, underlying drivers, and distinctive characteristics shaping regional adoption of single-cell analysis technologies.

Quantitative Market Comparison: North America vs. Asia-Pacific

Table 1: Regional Market Size and Growth Projections

| Region | Market Size (2024) | Projected Market Size | CAGR (%) | Projection Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | $1.2 - $1.7 billion [33] | $2.1 billion [33] | 11.8% [33] | 2028 |

| Asia-Pacific | $550 million [34] | $1.375 billion [34] | 20.1% [34] | 2025 |

Table 2: Country-Level Market Analysis Within Regions

| Country | Market Characteristics | Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. | Largest national market ($1.2B in 2023) [33] | Strong biotech R&D, personalized medicine focus, major player headquarters [33] [4] |

| Canada | $200M in 2023, projected $370M by 2028 [33] | Strong research ecosystem, government funding for biotech [33] |

| China | 38.17% of APAC revenue in 2024 [35] | Government genomics initiatives, "Human Spatiotemporal Genomics" project [35] |

| Japan | Largest APAC market share in 2019 [34] | Large geriatric population, focus on personalized medicine [34] |

| India | Projected 18.45% CAGR [35] | BioE3 blueprint targeting $300B bioeconomy by 2030 [35] |

The data reveals a clear pattern of North American dominance in current market value, with the United States serving as the primary engine of growth in this region. The U.S. market alone is valued at approximately $1.2 billion in 2023 and is expected to reach $2.1 billion by 2028, growing at a CAGR of 11.8% [33]. This represents the largest national market for single-cell analysis technologies globally, driven by advanced research infrastructure, substantial R&D investment, and concentration of major industry players.

Conversely, the Asia-Pacific region, while currently smaller in absolute market size, demonstrates markedly faster growth potential. The region is poised to grow at a CAGR of 20.1% from 2020 to 2025, propelled by increasing research investments, expanding biotechnology sectors, and government-backed life science initiatives [34]. China dominates the APAC landscape, accounting for 38.17% of regional revenue in 2024, with India projected to achieve the highest regional CAGR of 18.45% [35]. Japan maintains a strong position with its established research infrastructure and focus on addressing challenges posed by its aging population.

Market Drivers and Constraints Analysis

North American Market Drivers

The North American market's leadership position stems from several structural advantages. The region benefits from substantial funding from government and private sources, particularly through organizations like the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which has allocated $2.7 billion for precision medicine initiatives between 2022-2025 [3]. This financial support accelerates technology adoption and infrastructure development. Furthermore, the presence of major industry players such as 10x Genomics, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Bio-Rad creates a synergistic ecosystem of innovation, product development, and technical support [4]. The strong focus on personalized medicine and advanced healthcare infrastructure also drives adoption, particularly in clinical applications like oncology and immunology where single-cell insights provide critical diagnostic and therapeutic guidance [33] [3].

Asia-Pacific Growth Accelerators

The rapid growth in Asia-Pacific markets is fueled by distinct regional factors. Government-led initiatives play a pivotal role, with China's "Human Spatiotemporal Genomics" mega-project mobilizing 190 research teams and India's BioE3 blueprint targeting a $300 billion bioeconomy by 2030 [35]. These national strategies create substantial demand for single-cell technologies and associated reagents. Additionally, the region is experiencing rapidly expanding biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors, increasing both research capacity and market potential. The growing prevalence of chronic diseases and increasing healthcare investment further stimulate adoption, particularly as single-cell technologies become more accessible and cost-effective [35]. Notably, countries like Japan and South Korea are leveraging their technological manufacturing capabilities to develop domestic single-cell analysis platforms, reducing dependency on imports and fostering local innovation [34] [35].

Shared Market Constraints

Despite their different developmental trajectories, both regions face similar constraints. The high cost of instruments and reagents remains a significant barrier, particularly for smaller laboratories and research institutions [4]. This challenge is especially pronounced in emerging APAC markets where research budgets may be more constrained. Technical complexity and the need for specialized expertise also limit broader adoption, with a pronounced shortage of bioinformatics professionals capable of managing the complex data outputs from single-cell experiments [35] [7]. Additionally, both regions face challenges related to data management and analysis, as single-cell workflows generate massive datasets requiring sophisticated computational infrastructure and analytical pipelines [36].

Technological and Application Focus

Regional Technology Adoption Patterns

Table 3: Preferred Technologies and Applications by Region

| Technology/Application | North America Focus | Asia-Pacific Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Leading Technique | Flow cytometry (34.8% market share) [37] | Flow cytometry and next-generation sequencing [35] |

| Growth Technique | Multi-omics integration | Next-generation sequencing (17.23% CAGR) [35] |

| Primary Application | Cancer research (52.18% revenue in 2024) [35] | Cancer research and increasing immunology applications [34] [35] |

| Emerging Trend | Spatial transcriptomics, AI integration | Spatial transcriptomics, automation [35] [7] |

| End-User Segment | Academic & research laboratories, biotech/pharma | Academic & research laboratories (46.74% share in 2024) [35] |

Technological adoption patterns reveal both convergence and divergence between regions. Flow cytometry dominates both markets due to its established infrastructure and versatility, capturing 34.8% of the product segment in North America [37]. However, next-generation sequencing demonstrates particularly strong growth potential in Asia-Pacific, with a projected CAGR of 17.23% as sequencing costs decline and applications expand [35]. Both regions are increasingly embracing multi-omics approaches that integrate genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics at the single-cell level, providing more comprehensive biological insights [3].

Application priorities also show regional variation, though cancer research represents the dominant application globally, accounting for 52.18% of revenue in 2024 [35]. North American markets show stronger adoption in neurology and immunology applications, while Asia-Pacific demonstrates growing focus on infectious disease research and agricultural applications [35]. The end-user landscape is similarly segmented, with academic and research institutions representing the largest user base in both regions, though biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies represent the fastest-growing segment in Asia-Pacific with a 17.68% CAGR [35].

Experimental Methodology for Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis

The evaluation of single-cell analysis tools relies on standardized experimental and computational workflows. The core methodology for scRNA-seq data generation and analysis follows a structured pipeline that ensures reproducibility and accuracy in cell type identification and characterization.

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq Experimental Workflow. The process spans from initial experimental design through computational analysis to biological interpretation.

Experimental Design and Single-Cell Isolation

The foundational stage involves careful experimental design considering factors including cell number requirements, platform selection, and potential technical biases. Cell isolation employs either plate-/microfluidic-based methods (e.g., Fluidigm C1) with higher sensitivity but lower throughput, or droplet-based methods (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) enabling analysis of thousands of cells simultaneously with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [36]. The selection between these approaches depends on research questions, cell type characteristics, and available resources. For specialized cells like neurons or adult cardiomyocytes, single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) serves as a valuable alternative when intact cell isolation proves challenging [36].

Sequencing and Quality Control

Following library preparation and sequencing, raw data undergoes rigorous quality control (QC) to remove technical artifacts. The QC process involves both cell-level filtering (removing low-quality cells with <500 genes or >20% mitochondrial counts) and gene-level filtering (removing rarely detected genes) [36]. Specialized tools like FastQC assess read quality, while Trimmomatic or cutadapt remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [36]. Crucially, doublet detection algorithms like Scrublet or DoubletFinder identify and remove multiple cells mistakenly labeled as single cells, a common issue in droplet-based methods affecting 5-20% of cell barcodes [36].

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis phase begins with normalization to address technical variability between cells, followed by feature selection to identify highly variable genes driving cellular heterogeneity [36]. Dimensionality reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) reduce computational complexity while preserving biological signals [36]. Clustering algorithms then group cells based on transcriptional similarity, revealing distinct cell populations. The critical cell type annotation step employs either manual cluster annotation based on marker genes or automated classification methods [38]. Benchmarking studies have evaluated 22 classification methods, with support vector machine (SVM) classifiers demonstrating superior performance across diverse datasets [38]. Finally, downstream analysis includes trajectory inference (pseudotime analysis), differential expression testing, and cell-cell communication prediction, extracting biological insights from the processed data [36].

Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Analysis

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation Kits | BD Rhapsody Cartridges, 10x Genomics Chromium Chips | Partition individual cells into oil droplets with barcoded beads for transcript capture |

| Library Preparation Kits | SMARTer Ultra Low Input RNA Kit, Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Amplify and convert single-cell RNA into sequencing-ready libraries |

| Assay Kits | Chromium GEM-X Single Cell Gene Expression v4, BD OMICS-One XT WTA Assay | Enable targeted analysis of gene expression, immune profiling, or whole transcriptome analysis |

| Enzymes & Master Mixes | Reverse Transcriptase, PCR Master Mixes | Facilitate cDNA synthesis and amplification from minimal RNA input |

| Barcodes & Oligonucleotides | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), Cell Barcodes | Tag individual molecules and cells to track them through sequencing workflow |

| Quality Control Reagents | Viability Stains, RNA Quality Assays | Assess cell integrity and RNA quality before library preparation |

The single-cell analysis workflow relies on specialized reagents and consumables that constitute a significant portion of the market revenue. The consumables segment accounted for 56.1-58.12% of 2024 revenue, reflecting their recurring nature across experiments [35] [7]. These reagents enable the precise capture, processing, and analysis of individual cells while minimizing technical variability. Key innovations include barcoding systems that label individual molecules and cells, allowing thousands of cells to be processed simultaneously while maintaining sample identity [36]. Recent developments focus on increasing affordability and accessibility, with companies like 10x Genomics introducing technologies aimed at reducing costs to one cent per cell for reagent components [35]. Additionally, robotics-compatible reagent kits from manufacturers like BD enable automation of single-cell workflows, demonstrating 45% reduction in processing time and 30% decrease in human error rates compared to manual methods [3].

Future Outlook and Regional Trajectories

The future evolution of single-cell analysis technologies will be characterized by increasing integration, automation, and accessibility. Between 2025-2035, the market is expected to shift from transcriptomics-focused platforms toward integrated multi-omics systems capable of simultaneous genomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiling at single-cell resolution [37]. The incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning will become increasingly critical for managing complex datasets and extracting biological insights, with investments in AI-driven analytics for biological data growing by 45% between 2021-2023 [3].

Regionally, North America is expected to maintain its leadership position through continued innovation and early adoption of emerging technologies like spatial transcriptomics and real-time imaging mass cytometry [37]. The Asia-Pacific region will continue its rapid growth, potentially surpassing European market share within the forecast period, driven by expanding research infrastructure and strategic government investments. Emerging markets in Latin America and the Middle East will present new growth opportunities as single-cell technologies become more accessible and cost-effective [33].

The convergence of technological advancements across microfluidics, sequencing, and computational analysis will further democratize single-cell technologies, expanding their application beyond specialized research centers to clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development. This evolution will cement single-cell analysis as an indispensable tool for understanding cellular biology and advancing precision medicine initiatives globally.

A Guide to Leading Bioinformatics Tools: From Foundational Platforms to AI-Powered Solutions

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the investigation of gene expression at the individual cell level, uncovering cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell types, and illuminating developmental trajectories [10] [39]. As the scale and complexity of scRNA-seq experiments have grown, with datasets now routinely encompassing millions of cells, the computational tools used to analyze this data have evolved accordingly [40]. In the current landscape of 2025, two foundational platforms have emerged as the dominant frameworks for scRNA-seq analysis: Seurat, based in the R programming language, and Scanpy, based in Python [10] [39] [40].

Despite implementing similar analytical workflows, these tools differ significantly in their computational approaches, default parameters, and performance characteristics [10] [41]. This guide provides an objective comparison of Scanpy and Seurat, synthesizing current benchmarking data and experimental findings to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals select the optimal tool for their large-scale scRNA-seq projects. We present quantitative performance comparisons, detailed experimental protocols from published evaluations, and practical implementation guidance to inform tool selection within the broader context of single-cell analysis research.

Scanpy: Python-Based Scalability

Scanpy is an open-source Python library developed by the Theis Lab, specifically designed for analyzing single-cell gene expression data [39] [42]. As part of the growing scverse ecosystem, Scanpy provides a comprehensive toolkit for the entire analytical workflow, from preprocessing and visualization to clustering, trajectory inference, and differential expression testing [42] [40]. Its architecture, built around the AnnData object, optimizes memory usage and enables scalable analysis of datasets exceeding one million cells [40]. A key strength of Scanpy lies in its seamless integration with other Python libraries for scientific computing (NumPy, SciPy) and visualization (Matplotlib), making it particularly appealing for data scientists already working within the Python ecosystem [39].

Seurat: R-Based Comprehensive Framework

Seurat, developed by the Satija Lab, is one of the earliest and most widely adopted R-based toolkits for scRNA-seq analysis [39] [41]. Known for its robust and comprehensive feature set, Seurat has evolved through multiple versions to support increasingly complex analytical needs [39]. In 2025, Seurat offers native support for diverse data modalities, including spatial transcriptomics, multiome data (RNA + ATAC), and protein expression via CITE-seq [40]. Its modular workflow design integrates well with the broader Bioconductor ecosystem and other R packages for biological data analysis, making it a versatile choice for bioinformaticians proficient in R [39] [40].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Analytical Workflow Output Differences

Recent comparative studies have revealed that despite implementing ostensibly similar workflows, Seurat and Scanpy produce meaningfully different results when analyzing the same dataset, even with default settings [10] [41]. The table below summarizes key quantitative differences observed when comparing Seurat v5 and Scanpy v1.9 using the PBMC 10k dataset:

Table 1: Quantitative Differences in Analytical Outputs Between Seurat and Scanpy

| Analysis Step | Metric of Comparison | Seurat v5.0.2 | Scanpy v1.9.5 | Degree of Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVG Selection | Jaccard Index (Overlap) | 2,000 HVGs | 2,000 HVGs | Jaccard Index: 0.22 (Low overlap) |

| PCA | Proportion of Variance (PC1) | Higher by ~0.1 | Lower by ~0.1 | Noticeable difference in variance explained |

| SNN Graph | Median Neighborhood Similarity | Larger neighborhoods | Smaller neighborhoods | Median Jaccard Index: 0.11 (Low similarity) |

| Clustering | Cluster Agreement | Different cluster boundaries | Different cluster boundaries | Low agreement in cluster assignments |

| Differential Expression | Significant Marker Genes | ~50% more genes identified | Fewer genes identified | Jaccard Index: 0.62 (Moderate overlap) |

These differences stem from divergent default algorithms and parameter settings at each analytical stage [41]. For example, the low overlap in highly variable gene (HVG) selection (Jaccard index: 0.22) arises from Seurat's default use of the "vst" method versus Scanpy's default "seurat" flavor, which are fundamentally different algorithms [10] [43] [41]. Similarly, differences in PCA results emerge from Seurat's default value clipping during scaling and lack of regression, contrasted with Scanpy's default regression by total counts and mitochondrial content [41].

Computational Performance and Scalability

Benchmarking studies have evaluated the computational performance of both tools across datasets of varying sizes. The table below summarizes performance metrics based on historical benchmarking data:

Table 2: Computational Performance and Scalability Comparison

| Performance Metric | Scanpy | Seurat | Context and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Speed | Generally faster for large datasets | Slightly slower for very large datasets | Python-based tools often show speed advantages [39] |

| Memory Efficiency | Optimized for large datasets | Efficient, but may require more resources | Scanpy's AnnData object is memory-optimized [40] |

| Hardware Utilization | Effective multi-core support | Good parallelization capabilities | Both benefit from sufficient RAM and fast processors [44] |

| Scalability Limit | >1 million cells | >1 million cells | Both handle large-scale data [44] [40] |

| Cloud Compatibility | Excellent with Dask integration | Good with R cloud implementations | Scanpy's Dask compatibility is experimental but promising [42] |

A benchmark study from 2019, while dated, provides specific context for performance comparisons. When analyzing a dataset of 378,000 bone marrow cells, Pegasus (a Scanpy-based framework) and Scanpy demonstrated faster processing times compared to Seurat, though all tools successfully handled this scale of data [44]. It's important to note that both tools have undergone significant optimization since these benchmarks, and actual performance depends heavily on specific hardware, dataset characteristics, and analysis parameters.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for Tool Comparison

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons between Scanpy and Seurat, researchers have developed standardized evaluation protocols. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of scRNA-seq analysis where tool differences emerge:

Key Experimental Steps and Parameters:

Input Data Preparation: Studies typically begin with a standardized cell-gene count matrix, often from public repositories like the 10x Genomics PBMC dataset [41]. The same matrix serves as input for both tools.

Quality Control and Filtering: Both tools apply similar filtering thresholds - removing cells with fewer than 200 detected genes and genes detected in fewer than 3 cells [45] [41]. At this stage, outputs are nearly identical between tools [41].

Normalization: Researchers typically apply log normalization with identical scale factors (10,000 counts per cell), producing equivalent results when using the same input matrix [43] [41].

Highly Variable Gene Selection: This represents the first major divergence point. The standard protocol applies each tool's default HVG selection method: Seurat's "vst" versus Scanpy's "seurat" flavor, selecting 2,000 HVGs in each case [43] [41]. The Jaccard index quantifies the overlap between resulting gene sets.

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: PCA is performed using default parameters, followed by construction of k-nearest neighbor graphs, Louvain/Leiden clustering, and UMAP visualization [45] [41]. Differences in graph connectivity and cluster assignments are quantified using metrics like Jaccard similarity.

Benchmarking Batch Correction Performance

Batch effect correction represents a critical capability for large-scale scRNA-seq studies integrating multiple datasets. Research has specifically evaluated Scanpy-based batch correction methods, with implications for tool selection:

Table 3: Scanpy-Based Batch Correction Method Performance

| Method | Algorithm Type | Performance | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regress_Out | Linear regression | Moderate effect removal | Fastest |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes framework | Effective for known batches | Moderate speed |

| MNN_Correct | Mutual Nearest Neighbors | Preserves biological variation | Slower for large data |

| Scanorama | Randomized SVD + MNN | High performance for large datasets | Good scalability |

A 2020 study comparing these methods found that Scanorama generally outperformed other approaches in batch mixing metrics while preserving biological variation, particularly for large-scale integrations [45]. The study also noted that Scanpy-based methods generally offered faster processing times compared to Seurat's integration methods, though Seurat's anchor-based integration remains robust and widely used [45].

Successful large-scale scRNA-seq analysis requires both computational tools and appropriate data resources. The following table outlines key components of the experimental infrastructure:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Item Name | Type/Function | Usage in scRNA-seq Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger | Data Processing Pipeline | Converts 10x Genomics RAW FASTQ files into gene-count matrices [41] |

| kallisto-bustools | Open-Source Alignment | Alternative to Cell Ranger for fast, flexible count matrix generation [41] |

| Harmony | Batch Correction Algorithm | Integrates datasets across experiments and platforms [40] |

| scvi-tools | Deep Learning Framework | Probabilistic modeling for batch correction and imputation [40] |

| VELOCYTO | RNA Velocity Analysis | Infers directional cellular transitions from spliced/unspliced RNAs [40] |

| SingleCellExperiment | R Data Container | Standardized object for Bioconductor single-cell workflows [40] |

| AnnData | Python Data Structure | Scanpy's native format for efficient large-scale data handling [42] [40] |

| BBrowserX | Commercial Platform | Enables no-code exploration and visualization of results [46] [47] |

Practical Implementation Guidelines

Decision Framework for Tool Selection

Choosing between Scanpy and Seurat involves multiple considerations beyond mere performance metrics. The following diagram outlines key decision factors:

Key Selection Criteria:

Programming Language Proficiency: The single most important factor is often existing expertise. Python-centric teams will find Scanpy more natural, while R-oriented groups may prefer Seurat [39]. This consideration extends to future hiring and team skill development.

Dataset Scale and Performance Requirements: For extremely large datasets (millions of cells), Scanpy may offer performance advantages due to its optimized memory handling and integration with high-performance Python libraries [39] [40]. For standard-scale datasets, both tools perform adequately.

Analysis Type and Advanced Method Needs: Seurat provides robust support for spatial transcriptomics, multi-modal integration (RNA+ATAC), and its anchor-based integration method [40]. Scanpy excels in integration with deep learning approaches through scvi-tools and offers access to Python's machine learning ecosystem [40].

Usability and Learning Curve: Seurat offers extensive documentation, tutorials, and a relatively gentle learning curve, especially for researchers already familiar with R [39]. Scanpy has a steeper initial learning curve, particularly for those unfamiliar with Python, though its documentation has improved significantly [39].

Ecosystem and Integration Requirements: Consider the broader analytical context. Scanpy integrates seamlessly with the scverse ecosystem (Squidpy for spatial, Muon for multi-omics) and Python's data science stack [42] [40]. Seurat connects with Bioconductor, Monocle, and other R packages for specialized analyses [40].

Version Management and Reproducibility

A critical finding across comparative studies is that software version management significantly impacts reproducibility [10] [41]. Differences between Seurat versions (v4 vs. v5) or Scanpy versions (v1.4 vs. v1.9) can introduce variability comparable to differences between the tools themselves, particularly in differential expression analysis where algorithm changes affect results [10] [41].

Best Practices for Reproducible Analysis:

Version Documentation: Meticulously document exact software versions (including dependencies) in all analyses.

Version Consistency: Maintain the same software versions throughout a project to ensure consistent results.

Parameter Transparency: Record all parameters and non-default settings used in analytical workflows.

Containerization: Consider using Docker or Singularity containers to encapsulate complete computational environments.

Random Seed Setting: Set random seeds for stochastic processes (clustering, UMAP) to enhance reproducibility, though note that tool differences outweigh seed-induced variability [10].

Both Scanpy and Seurat represent mature, capable frameworks for large-scale scRNA-seq analysis, each with distinct strengths and characteristics. Scanpy excels in scalability and Python ecosystem integration, making it ideal for very large datasets and projects leveraging Python's machine learning capabilities. Seurat offers comprehensive multi-modal support and spatial transcriptomics integration, benefiting teams working within the R/Bioconductor ecosystem.

The documented differences in analytical outputs between these tools highlight the importance of tool consistency within research projects and transparent reporting of software versions and parameters. Rather than seeking a definitive "best" tool, researchers should select based on their specific project requirements, team expertise, and analytical priorities. As the single-cell field continues evolving with new technologies and computational methods, both Scanpy and Seurat remain foundational workhorses that will undoubtedly continue adapting to meet emerging research needs.