Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Protocols: A 2025 Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

This comprehensive guide explores the rapidly evolving landscape of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) protocols, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an essential resource for navigating this transformative technology.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Protocols: A 2025 Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores the rapidly evolving landscape of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) protocols, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an essential resource for navigating this transformative technology. The article covers foundational principles from cell isolation to data analysis, details major methodological approaches including full-length and 3'/5' end-counting techniques, and offers practical troubleshooting guidance for experimental optimization. Through comparative analysis of leading platforms and validation strategies, it equips readers to select appropriate protocols, avoid common pitfalls, and leverage scRNA-seq for groundbreaking discoveries in cellular heterogeneity, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development.

The Single-Cell Revolution: Unraveling Cellular Heterogeneity and Transcriptomic Complexity

The fundamental unit of life is the cell, and for decades, transcriptomic analysis was constrained by technological limitations that required researchers to study gene expression in pooled populations of thousands to millions of cells. Bulk RNA sequencing provided a population-average profile, effectively masking the rich heterogeneity inherent in biological systems [1] [2]. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a paradigm shift of extraordinary significance, enabling the precise measurement of gene expression at the resolution of individual cells [3]. This technological revolution has transformed our understanding of cellular identity, function, and interaction, particularly in complex tissues such as tumors, the developing brain, and the immune system.

The transition from bulk to single-cell analysis is not merely incremental improvement but a fundamental reconceptualization of biological inquiry. Where bulk sequencing viewed tissues as relatively homogeneous entities, single-cell technologies recognize them as complex ecosystems composed of diverse, interacting cell types and states [4]. This shift has profound implications for basic research and therapeutic development, allowing researchers to identify rare cell populations, trace developmental lineages, and understand the cellular underpinnings of disease with unprecedented precision [5] [6].

Technical Comparison: Bulk Versus Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The core distinction between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing lies in their initial handling of biological material. In bulk RNA-seq, RNA is extracted from an entire tissue sample or population of cells, processed collectively, and sequenced to generate an average expression profile for all genes across the entire cellular population [1] [3]. This approach effectively obscures differences between individual cells and cannot determine whether a transcript is expressed uniformly across all cells or highly expressed in a small subset.

In contrast, scRNA-seq begins with the physical or computational separation of individual cells, followed by library preparation and sequencing that maintains cell-of-origin information through genetic barcoding [3]. The 10x Genomics Chromium platform, for example, uses microfluidic partitioning to isolate single cells in gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs), where each bead contains oligonucleotides with unique cellular barcodes [3]. This allows subsequent computational attribution of sequenced reads to their individual cellular sources, enabling the reconstruction of entire transcriptomes for each cell.

Comparative Analysis of Capabilities and Limitations

The table below summarizes the key technical differences between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing approaches:

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of bulk versus single-cell RNA sequencing methodologies

| Feature | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [1] [3] | Individual cell level [1] [3] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~$300 per sample) [1] | Higher (~$500-$2000 per sample) [1] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, simpler analysis [1] | Higher, requires specialized computational methods [1] [2] |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited, masks diversity [1] [4] | High, reveals cellular subpopulations [1] [3] |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited, often missed [1] | Possible, can identify rare populations [1] [4] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher, detects more genes per sample [1] | Lower per cell, but captures more cell-type-specific genes [1] |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher, typically micrograms of RNA [1] | Lower, can work with single cells [1] |

| Splicing Analysis | More comprehensive [1] | Limited with 3'/5' end methods [1] [2] |

| Technical Noise | Lower, averages across cells [1] | Higher, includes amplification artifacts [2] |

| Primary Applications | Differential expression between conditions, biomarker discovery [1] [4] | Cell typing, developmental trajectories, tumor heterogeneity [1] [3] |

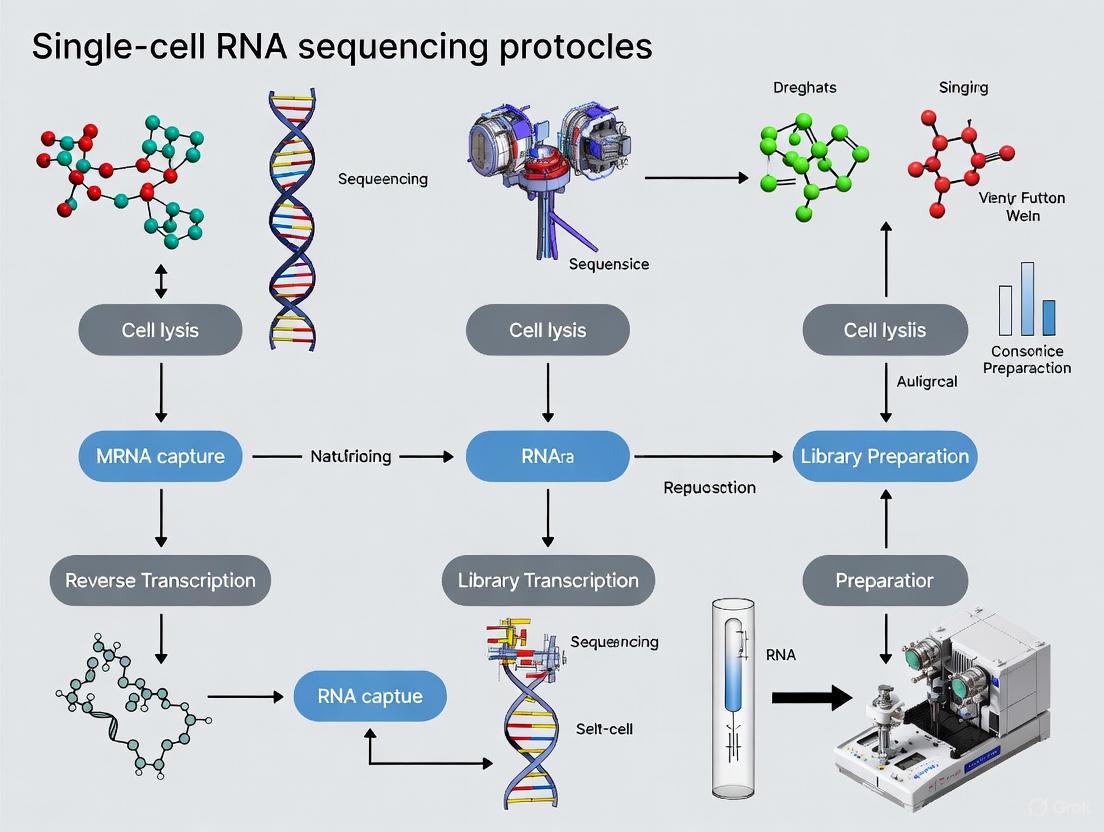

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental differences between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing approaches:

Figure 1: Experimental workflows for bulk versus single-cell RNA sequencing. Bulk sequencing (green) produces a population average, while single-cell sequencing (blue) maintains individual cell identity throughout the process, enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity.

Key Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Protocols and Methodologies

The scRNA-seq landscape has diversified rapidly, with numerous platforms and methodologies emerging, each with distinct advantages and limitations. These technologies primarily differ in their cell isolation strategies, transcript coverage, amplification methods, and use of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [2]. The choice of platform depends on research goals, sample type, and required throughput.

Table 2: Comparison of major single-cell RNA sequencing protocols and their characteristics

| Protocol | Isolation Strategy | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Amplification Method | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 | FACS | Full-length | No | PCR | Enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts; generates full-length cDNA [2] |

| Drop-Seq | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | High-throughput, low cost per cell; scalable to thousands of cells [2] |

| inDrop | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | IVT | Uses hydrogel beads; low cost per cell; efficient barcode capture [2] |

| CEL-Seq2 | FACS | 3'-only | Yes | IVT | Linear amplification reduces bias compared to PCR [2] |

| Seq-well | Droplet-based | 3'-only | Yes | PCR | Portable, low-cost, easily implemented without complex equipment [2] |

| SPLiT-Seq | Not required | 3'-only | Yes | PCR | Combinatorial indexing without physical separation; highly scalable and low cost [2] |

| MATQ-Seq | Droplet-based | Full-length | Yes | PCR | Increased accuracy in quantifying transcripts; efficient detection of transcript variants [2] |

Specialized Methodologies: Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing

For tissues that are difficult to dissociate or archived samples, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (sNuc-seq) provides a valuable alternative to conventional scRNA-seq [7]. This approach sequences RNA from isolated nuclei rather than whole cells, overcoming challenges associated with cell integrity and dissociation.

The DroNc-seq method adapts droplet-based approaches for nuclei, specifying appropriate concentrations for bead and nucleus loading to avoid multiple nuclei per droplet [7]. For particularly sensitive tissues like neuronal samples, hypotonic-mechanical cell lysis using hypotonic lysis buffer and controlled pipetting enables controllable tissue disruption, balancing yield and purity [7].

sNuc-seq has proven particularly valuable in neurobiology, where it has been used to distinguish cell types and neuronal subtype composition, and to detect and quantify neuronal activity in mammalian brains at high temporal resolution [7]. A limitation of this approach is the loss of anatomical context due to tissue dissociation.

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful scRNA-seq experiments require specialized reagents and tools designed to handle the unique challenges of working with minute quantities of starting material while maintaining cell integrity and transcript capture efficiency.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for single-cell RNA sequencing workflows

| Reagent Category | Function | Examples/Features |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability Kits | Distinguish live/dead cells | Fluorescent dye-based assays for flow cytometry validation |

| Cell Lysis Buffers | Release RNA while preserving integrity | Detergent-based (e.g., Triton) or hypotonic buffers [7] |

| Reverse Transcription Mix | Convert mRNA to cDNA | Includes cell barcodes, UMIs, and template-switching oligonucleotides [3] |

| cDNA Amplification Kits | Amplify limited cDNA | PCR-based with optimized cycles for minimal bias [2] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries | Include indexing for sample multiplexing [8] |

| Bead-Based Cleanup | Purify nucleic acids between steps | SPRI or magnetic bead-based systems |

| Commercial Platforms | Integrated workflows | 10x Genomics Chromium, Fluidigm C1 [8] [2] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Enhancing Target Identification and Validation

The pharmaceutical industry has embraced scRNA-seq as a transformative tool throughout the drug development pipeline. In target identification, scRNA-seq enables the discovery of novel cellular and molecular targets by precisely characterizing cell types and states associated with disease pathology [5] [6]. In oncology, for example, scRNA-seq has revealed previously unappreciated heterogeneity within tumors, identifying rare subpopulations that may drive treatment resistance or disease progression [6].

During target validation, scRNA-seq data provides crucial evidence for establishing target credibility through comprehensive analysis of disease biology, target biology, and druggability [6]. The technology also facilitates assessment of translational relevance in preclinical models by enabling precise comparison of cellular composition, tissue heterogeneity, and rare cell phenotypes between models and human disease states [6].

Elucidating Drug Mechanisms of Action

ScRNA-seq provides unprecedented insights into drug mechanisms of action (MoA) by revealing how individual cells respond to therapeutic perturbations [5] [6]. Traditional high-throughput screening methods typically rely on coarse metrics like cell viability or specific marker expression. In contrast, scRNA-seq-enabled screens capture whole transcriptome responses across diverse cell types and states within heterogeneous populations [6].

This approach was exemplified by research on B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), where combined bulk and single-cell RNA-seq identified developmental states driving resistance and sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent asparaginase [3]. Similarly, the Watermelon high-complexity lentiviral barcode library enables simultaneous tracking of clonal lineage, proliferation status, and transcriptomic profiles in individual cells during drug treatment, providing powerful insights into resistance mechanisms [6].

Enabling Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification

ScRNA-seq has proven invaluable for biomarker discovery and patient stratification in clinical development [5] [6]. By characterizing mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance in cancers such as high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), scRNA-seq has identified cellular and molecular features predictive of treatment response [6]. In colorectal cancer, scRNA-seq has precisely defined prognostic biomarkers that enable more accurate patient stratification [6].

The technology also enhances minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring in oncology through single-cell mutation analysis that enables precise subclonal-level evaluations at lower detection limits and comprehensive analysis of subclone evolution throughout treatment [6]. This approach effectively identifies resistant subclones that may lead to disease relapse.

The following diagram illustrates how scRNA-seq informs critical decision points throughout the drug development pipeline:

Figure 2: Applications of scRNA-seq across the drug development pipeline. scRNA-seq informs critical decisions from initial target identification through clinical application by providing cellular-resolution insights into disease mechanisms and treatment responses.

Bioinformatics Considerations for scRNA-seq Data

Unique Computational Challenges

The analysis of scRNA-seq data presents distinct computational challenges compared to bulk RNA-seq. ScRNA-seq data is characterized by high dimensionality, technical noise, and sparsity due to dropout events where transcripts fail to be detected even when expressed [2] [9]. These characteristics necessitate specialized computational approaches at each stage of the analysis pipeline.

The standard scRNA-seq workflow includes quality control to remove low-quality cells and multiplets, normalization to account for technical variability, feature selection to identify informative genes, dimensionality reduction to visualize and explore data structure, clustering to identify cell populations, and differential expression analysis to characterize population differences [2] [9]. Additional specialized analyses include trajectory inference to reconstruct developmental processes and cell-type annotation using reference datasets.

Key Analytical Tools and Approaches

Several analytical strategies have been developed specifically to address the unique characteristics of scRNA-seq data. For batch effect correction, methods like Harmony and Seurat's integration approaches aim to remove technical variations while preserving biological signals [2]. For imputation, algorithms such as MAGIC and SAVER attempt to address sparsity by predicting dropout events, though must be applied cautiously to avoid introducing false signals [2].

Dimensionality reduction techniques like t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) are widely used to visualize high-dimensional scRNA-seq data in two or three dimensions, enabling the identification of cell clusters and patterns [9]. For differential expression analysis, methods like MAST and DESingle account for the unique statistical characteristics of single-cell data, including bimodality and sparsity.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of single-cell transcriptomics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory. Multi-omics approaches that combine scRNA-seq with measurements of chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq), protein expression (CITE-seq), and other molecular features provide increasingly comprehensive views of cellular states [10] [6]. Spatial transcriptomics technologies are addressing a key limitation of scRNA-seq by preserving and measuring the anatomical context of cells within tissues [1].

From a practical perspective, ongoing developments are making scRNA-seq more accessible and scalable. The recent introduction of the 10x Genomics GEM-X Flex Gene Expression assay is reducing costs by enabling higher-throughput experiments, while the Chromium Xo instrument offers a more affordable entry point to high-performance single-cell profiling [3]. These advancements are gradually alleviating the cost and technical barriers that have historically limited scRNA-seq adoption.

In conclusion, the paradigm shift from bulk to single-cell transcriptomic analysis has fundamentally transformed biological research and therapeutic development. By revealing the cellular heterogeneity that underlies biological systems, scRNA-seq has provided unprecedented insights into development, physiology, and disease mechanisms. As the technology continues to mature and integrate with complementary spatial and multi-omics approaches, its impact on basic research and drug development will undoubtedly expand, accelerating the development of more precise and effective therapeutics for complex diseases.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed transcriptomics by enabling the investigation of gene expression at the individual cell level. This technology provides unprecedented resolution, allowing researchers to dissect cellular heterogeneity, identify rare cell populations, and map complex biological systems in ways that were previously impossible with bulk RNA sequencing. By capturing the transcriptome of individual cells, scRNA-seq reveals the precise cellular diversity within tissues and organs, offering profound insights into development, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic discovery [11] [12]. This application note details the core principles, experimental workflow, and key technological innovations that empower scRNA-seq to achieve this remarkable resolution, providing researchers with a structured guide for implementing these powerful methodologies.

Traditional bulk RNA sequencing measures the average gene expression across thousands to millions of cells, effectively masking the unique transcriptional profiles of individual cells and rare cell types within a population [11]. The fundamental limitation of bulk sequencing lies in its inability to resolve cellular heterogeneity—the variation in gene expression, cell states, and developmental trajectories that exist even in seemingly homogeneous cell populations.

scRNA-seq technology, first conceptualized in 2009, overcame this limitation by enabling transcriptomic profiling at single-cell resolution [12]. This revolutionary approach has since evolved through numerous methodological improvements, allowing researchers to:

- Identify novel and rare cell types that are undetectable in bulk analyses [11]

- Map developmental trajectories and cell lineage relationships [11]

- Characterize complex tissue architectures and cellular microenvironments [2]

- Investigate tumor heterogeneity and cancer evolution [11]

- Advance personalized medicine through detailed cellular profiling [11]

The core value proposition of scRNA-seq lies in its capacity to capture the full spectrum of cellular diversity, providing a high-resolution view of biological systems that was previously unattainable.

Core Technological Principles

The Fundamental scRNA-seq Workflow

The power of scRNA-seq to resolve gene expression at unprecedented resolution stems from a sophisticated workflow that isolates, processes, and analyzes individual cells. The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage process:

Key Innovations Enabling Single-Cell Resolution

Several technological breakthroughs have been essential for achieving true single-cell resolution:

Molecular Barcoding: Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) tag each individual mRNA molecule during reverse transcription, enabling accurate quantification by correcting for PCR amplification biases and ensuring that each transcript is counted precisely [11] [12]. Cell barcodes uniquely label all transcripts from a single cell, allowing multiplexing of thousands of cells in a single experiment [13].

High-Throughput Cell Isolation: Droplet-based microfluidics enables simultaneous processing of thousands of individual cells by encapsulating single cells in nanoliter droplets with barcoded beads, dramatically increasing throughput while reducing costs [11] [14].

Sensitive Amplification Methods: Both polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and in vitro transcription (IVT) amplification methods have been optimized to handle the minute quantities of RNA present in single cells (typically 10-50 pg total RNA per cell) while maintaining quantitative accuracy [11] [12].

Comparative Analysis of scRNA-seq Methodologies

Protocol Selection Guide

The choice of scRNA-seq protocol significantly impacts experimental outcomes, including the number of cells that can be processed, genes detected per cell, and specific applications supported. The table below summarizes key characteristics of major scRNA-seq technologies:

Table 1: Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Protocols and Their Capabilities

| Protocol | Throughput | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Amplification Method | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 | Low-throughput (1-1,000 cells) | Full-length | No | PCR | Enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts; detects isoforms [2] |

| 10X Genomics Chromium | High-throughput (>10,000 cells) | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | High cell throughput; cost-effective; standardized workflow [14] |

| Drop-Seq | High-throughput (1,000-10,000 cells) | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | Low cost per cell; open-source platform [2] |

| CEL-Seq2 | Medium throughput (100-1,000 cells) | 3'-end | Yes | IVT | Reduced amplification bias; strand-specific [14] |

| MATQ-Seq | Medium throughput (100-1,000 cells) | Full-length | Yes | PCR | High accuracy in quantifying transcripts; detects rare variants [2] |

| Seq-Well | High-throughput (10,000-100,000 cells) | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | Portable; low-cost; works with limited equipment [2] |

Cost and Performance Considerations

When selecting a scRNA-seq approach, researchers must balance multiple factors, including cost, sensitivity, and throughput:

Table 2: Performance and Economic Considerations of scRNA-seq Methods

| Protocol | Approximate Cost per Cell | Average Genes Detected per Cell | Cell Isolation Strategy | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 | $1.50-$2.50 | 6,500-10,000 | FACS/Fluidigm C1 | Rare cell characterization; isoform analysis [14] |

| 10X Genomics | ~$0.50 | 4,000-7,000 | Droplet-based | Large-scale atlas projects; heterogeneous tissues [14] |

| Drop-Seq | $0.10-$0.20 | 2,000-6,000 | Droplet-based | Large-scale screening; budget-conscious studies [14] |

| CEL-Seq2 | $0.30-$0.50 | 5,000-7,000 | FACS/Microfluidics | Studies requiring strand-specific information [14] |

| Split-seq | ~$0.01 | 3,000-7,000 | Combinatorial indexing | Ultra-high throughput; fixed or hard-to-dissociate samples [2] [14] |

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful scRNA-seq experiments require carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for working with minute quantities of cellular material. The following toolkit outlines essential components:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Barcoding Beads | Delivery of oligonucleotides containing cell barcodes, UMIs, and poly(T) primers for mRNA capture | Bead composition affects capture efficiency; hydrogel vs. magnetic properties [13] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts captured mRNA into cDNA; template-switching activity enhances full-length coverage | Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MMLV) RT with high processivity and strand-switching activity is preferred [12] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Random nucleotide sequences that uniquely tag individual mRNA molecules to correct amplification bias | Typically 6-12 nucleotides; must have sufficient complexity to label all transcripts [11] [14] |

| Template Switching Oligo | Enables addition of universal primer sequences to cDNA during reverse transcription | Critical for full-length protocols; improves cDNA yield [12] |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | disrupts cell membrane to release RNA while maintaining RNA integrity | Must inactivate RNases without interfering with downstream enzymatic steps [11] |

| mRNA Capture Primers | Poly(T) primers selectively bind polyadenylated mRNA while excluding ribosomal RNA | Length and modifications affect specificity and efficiency [11] |

Computational Analysis Pipeline

The unprecedented resolution of scRNA-seq generates complex, high-dimensional data that requires specialized computational approaches. The analysis pipeline transforms raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights:

Addressing Computational Challenges

The high-dimensional nature of scRNA-seq data presents unique analytical challenges that require specialized approaches:

Dimensionality Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) transforms gene expression data into a lower-dimensional space while retaining biological information [15]. Subsequent visualization techniques like t-SNE and UMAP further reduce dimensions to create intuitive 2D or 3D representations of cell relationships [15].

Batch Effect Correction: Technical variations between experiments must be addressed to distinguish true biological differences from artifacts [11]. Methods like Harmony and Combat integrate datasets while preserving biological heterogeneity.

Dropout Imputation: The high sparsity of scRNA-seq data, with many zero counts for genuinely expressed genes, requires sophisticated imputation algorithms to distinguish technical zeros from true biological absence of expression [15].

Applications Enabled by Unprecedented Resolution

The resolution provided by scRNA-seq has opened new frontiers across biological research and therapeutic development:

Characterizing Cellular Heterogeneity

scRNA-seq excels at decomposing complex tissues into their constituent cell types, enabling researchers to:

- Identify novel cell types and states without prior knowledge of marker genes [11]

- Reconstruct developmental trajectories using pseudotemporal ordering algorithms [12]

- Map cellular ecosystems in complex tissues like the tumor microenvironment [11] [2]

Advancing Disease Understanding and Treatment

The technology has particularly transformative applications in biomedical research:

- Tumor Heterogeneity Mapping: Characterizing the diverse cell populations within cancers, including rare treatment-resistant subclones that drive recurrence [11] [12].

- Biomarker Discovery: Identifying novel cellular and molecular signatures for early disease detection, prognosis, and treatment response prediction [11].

- Drug Mechanism Elucidation: Understanding how therapeutics affect specific cell types within complex tissues, revealing both intended and off-target effects [2].

- Personalized Medicine: Informing treatment selection based on the specific cellular composition of patient samples [11].

Future Directions and Protocol Optimization

As scRNA-seq continues to evolve, several emerging trends are shaping its development:

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining transcriptomic data with epigenetic, proteomic, and spatial information provides a more comprehensive view of cellular states [10] [8].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Mapping gene expression within tissue context preserves architectural relationships while maintaining single-cell resolution [12].

- Improved Accessibility: Decreasing costs and simplified protocols are making scRNA-seq available to broader research communities [10] [8].

- Standardization Efforts: Development of consensus protocols and analytical frameworks improves reproducibility across laboratories [8].

Single-cell RNA sequencing represents a paradigm shift in transcriptomics, providing unprecedented resolution to investigate cellular heterogeneity and complexity. Through sophisticated molecular barcoding, high-throughput cell isolation, and sensitive amplification methods, scRNA-seq enables researchers to dissect biological systems at previously unimaginable resolution. As protocols continue to improve and costs decrease, this transformative technology will increasingly become an essential tool for understanding fundamental biology, unraveling disease mechanisms, and developing novel therapeutics. The continued refinement of both experimental and computational approaches will further enhance the resolution and accessibility of scRNA-seq, solidifying its role as a cornerstone of modern biological research.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a transformative advancement in genomic technologies, enabling the profiling of gene expression at the resolution of individual cells. Unlike conventional bulk RNA sequencing, which averages signals across thousands to millions of cells, scRNA-seq unveils the cellular heterogeneity within complex tissues, much like distinguishing individual ingredients in a smoothie rather than just tasting the final blend [16]. This Application Note provides a detailed framework of the essential workflow from cell isolation to sequencing library preparation, contextualized within broader thesis research on single-cell protocols. The technical guidance and standardized protocols presented herein are designed to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in implementing robust and reproducible single-cell studies.

The standard scRNA-seq workflow encompasses a series of interconnected steps, each critical to the quality and reliability of the final data. The following diagram provides a high-level visualization of this process, from sample preparation through data analysis.

Critical Initial Steps: Sample and Single-Cell Preparation

Generation of Single-Cell Suspensions

The initial phase of sample preparation is fundamental, as the quality of the single-cell suspension directly impacts all subsequent steps. The optimal approach varies significantly by sample type.

- Tissues: Fresh tissues require mechanical dissociation and often enzymatic digestion to achieve a single-cell suspension while minimizing cell stress and RNA degradation [17]. Protocols must be optimized for specific tissue types due to varying sensitivity to suspension composition and handling techniques [18].

- Cryopreserved Samples: For archived or difficult-to-dissociate tissues, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides a powerful alternative. snRNA-seq has been demonstrated to produce results similar to scRNA-seq and is particularly applicable to frozen tissues, including human snap-frozen liver biopsies [19]. A specialized nuclei isolation protocol involves tissue lysis in a cold buffer containing IGEPAL CA-630 (a detergent), followed by mincing, filtering through a 30 μm strainer, and centrifugation to form a nuclei pellet [19].

A key consideration during this stage is minimizing the presence of nuclear aggregates, dead cells, cellular debris, and potential inhibitors of reverse transcription to obtain high-quality data [18]. Cell viability should be assessed using markers like Calcein AM (for live cells) and membrane-impermeant DNA stains like EthD-1 (for dead cells) during cell sorting [20].

Single-Cell Isolation Technologies

Once a suspension is obtained, individual cells must be isolated for processing. The following table compares the primary methods used.

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell Isolation Methods

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Features | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidics (e.g., 10x Genomics) | Partitions cells into nanoliter-scale droplets in an oil emulsion [17]. | High (thousands of cells/sec) [17] | High scalability, integrated barcoding. | Large-scale studies requiring 3,000–10,000 cells per sample [16]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Uses lasers and fluidics to sort single cells based on fluorescence and scatter properties [17]. | Medium | High purity, enables pre-selection of cells based on specific surface markers. | Studies requiring precise selection of specific cell populations from a heterogeneous mix. |

| Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) | Separates cells using antibody-coated magnetic beads [17]. | High | Cost-effective, achieves high purity (up to 98%) for immune and stem cells [17]. | Targeted enrichment or depletion of specific cell types. |

| Manual Cell Picking | Physically picks individual cells under a microscope. | Very Low | Maximum control over cell selection. | Studies with a very small number of rare or specific cells. |

Core Protocol: Library Preparation via Template-Switching

A widely adopted method for library preparation, particularly for full-length transcript analysis, is the SMART-Seq2 protocol, which leverages the template-switching mechanism [20]. The following diagram illustrates the key molecular steps in this process.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

This protocol is adapted from the SMART-Seq2 method and is typically performed in a 96-well plate format [20].

Step 1: Single-Cell Lysis

- Prepare a lysis buffer containing guanidine thiocyanate or a commercial buffer like Buffer TCL with 1% 2-mercaptoethanol [20].

- Sort single cells directly into the lysis buffer-containing wells using FACS.

- Centrifuge the plate and immediately freeze it at -80°C or proceed directly to cleanup.

Step 2: Lysate Cleanup and RNA Isolation

- Thaw the lysate plate on ice and centrifuge.

- Add Agencourt RNAClean XP SPRI beads (2.2 volumes relative to lysate) to each well to purify RNA. Incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature [20].

- Place the plate on a magnetic stand to separate beads from supernatant. Wash beads with ethanol and elute RNA in nuclease-free water.

Step 3: Reverse Transcription and Template-Switching

- Prepare a reverse transcription mix containing:

- SMARTScribe Reverse Transcriptase (with terminal transferase activity)

- SMARTer dNTP Mix

- Dithiothreitol (DTT)

- 3' SMART CDS Primer II A

- RNase Inhibitor

- Incubate for 90 minutes at 42°C. During reverse transcription, the enzyme adds a few non-templated deoxycytidines (dC) to the 3' end of the completed cDNA strand.

- The SMARTer II A Oligonucleotide (Template-Switch Oligo, TSO), which contains riboguanosines (rGrGrG) at its 3' end, binds to these dC residues, allowing the reverse transcriptase to "switch" templates and continue replicating the TSO. This creates cDNA with known universal priming sequences on both ends [20].

- Prepare a reverse transcription mix containing:

Step 4: cDNA Amplification

- Add a PCR mix containing the IS PCR Primer and Advantage 2 Polymerase to the reaction.

- Amplify the cDNA using the following cycling conditions:

- 1 cycle: 95°C for 1 minute

- 20-25 cycles: 95°C for 15 seconds, 65°C for 30 seconds, 68°C for 6 minutes

- The number of cycles should be optimized based on input material to avoid over-amplification.

Step 5: Library Construction for Sequencing

- The amplified, full-length cDNA can be used to prepare sequencing libraries with kits such as the Illumina Nextera XT.

- In this step, the cDNA is incubated with a Tn5 transposase ("tagmentation") to fragment the DNA and simultaneously append sequencing adapters [20].

- Follow with a limited-cycle PCR to add full-length adapters and unique dual indices (i5 and i7) to each sample, allowing for sample multiplexing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for scRNA-seq Library Preparation

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| SPRI Beads | Purification and size selection of nucleic acids (RNA and cDNA) during cleanup steps. | Agencourt RNAClean XP Beads, Agencourt AMPure XP Beads [20]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Synthesizes first-strand cDNA from cellular RNA; specific kits enable template-switching. | SMARTer Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for Illumina Sequencing [20]. |

| PCR Amplification Kit | Amplifies cDNA to generate sufficient material for library preparation. | Advantage 2 PCR Kit [20]. |

| Library Prep Kit | Fragments cDNA and appends sequencing adapters and indices. | Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit [20]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA from degradation during the initial steps of the protocol. | Murine RNase Inhibitor [20]. |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Rapidly lyses cells and inactivates RNases to preserve RNA integrity. | Buffer TCL with 2-mercaptoethanol [20]. |

Platform Selection and Sequencing Specifications

Comparison of Commercial scRNA-seq Platforms

Choosing an appropriate technology is critical for experimental success. The following table summarizes key features of popular platforms.

Table 3: Comparison of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Technologies

| Technology / Platform | Isolation Method | Optimal Cell Number | Transcript Coverage | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Microfluidics (Droplet) | 3,000 – 10,000 [16] | 3' or 5' (Gene Expression) | High-throughput cell typing, immune profiling, multiomics (ATAC+Gene Expression) [21]. |

| SORT-seq | 384-well plates (FACS) | 384 – 1,500 [16] | 3' | Targeted studies with lower cell numbers [16]. |

| SMART-Seq2 | FACS/Microwells | Low throughput (96/384-well) | Full-length | Isoform detection, mutation analysis, low-input RNA-Seq [20]. |

| Illumina Single Cell 3' | Microfluidics (Droplet) | 5,000 - 200,000 (across kit sizes) [22] | 3' | Scalable projects from thousands to hundreds of thousands of cells [22]. |

The 10x Genomics Chromium Controller and iX/X Series instruments, for example, use microfluidics to partition single cells into gel beads-in-emulsion (GEMs), where each bead is coated with barcoded oligonucleotides for cell-specific labeling. This system can process 1–8 samples in one run, loading up to 10,000 cells per sample [21].

Sequencing Read Depth and Library Specifications

Adequate sequencing depth is crucial for detecting a sufficient number of genes per cell and achieving meaningful biological insights.

Table 4: Sequencing Read Depth Recommendations

| Platform / Kit | Recommended Loaded Cells | Required Sequencing Reads |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Single Cell 3' (T2) | 5,000 | 100 Million [22] |

| Illumina Single Cell 3' (T10) | 17,000 | 340 Million [22] |

| Illumina Single Cell 3' (T20) | 40,000 | 800 Million [22] |

| Illumina Single Cell 3' (T100) | 200,000 | 4 Billion [22] |

| General Guidance | - | 20,000 - 150,000 reads per cell [16] |

For library sequencing on Illumina platforms, the Illumina Single Cell 3' prep libraries require a minimum of 137 cycles: Read 1 (>45 bases for barcodes), i7 index (10 bases), i5 index (10 bases), and Read 2 (>72 bases for gene expression information) [22]. Final library loading concentrations vary by sequencer, for example, 210 pM for the NovaSeq 6000 and 190-200 pM for the NovaSeq X Series, both requiring a minimum of 1-2% PhiX control [22].

Downstream Data Analysis Workflow

Following sequencing, raw data must be processed to extract biologically meaningful information. The standard pipeline involves:

- Primary Analysis: Tools like Cell Ranger (for 10x Genomics data) process raw sequencing files to demultiplex samples, align reads to a reference transcriptome, and count unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to generate a gene-cell count matrix [23].

- Secondary Analysis in R/Python: The count matrix is imported into environments like R using the Seurat package or Bioconductor for quality control. This involves filtering cells based on metrics like the number of detected genes per cell and the percentage of mitochondrial reads, which indicates cell stress. Data is then normalized, scaled, and variable features are identified [23].

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Principal component analysis (PCA) is performed, followed by graph-based clustering and non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques like t-SNE or UMAP to visualize cell clusters [23].

- Biological Interpretation: Clusters are annotated into cell types by finding differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and comparing them to known marker genes. Further advanced analyses can include trajectory inference (pseudo-time analysis), RNA velocity, and gene regulatory network analysis [23].

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) marked a paradigm shift in transcriptomics, moving beyond the limitations of bulk RNA sequencing which could only provide averaged gene expression profiles across thousands of cells [24]. This technological revolution has enabled researchers to dissect cellular heterogeneity, identify rare cell types, and reconstruct developmental trajectories with unprecedented resolution [11] [25]. The evolution of scRNA-seq capabilities represents a journey of remarkable innovation, driven by advances in biochemistry, microfluidics, and computational biology. This application note traces the key technological milestones in scRNA-seq development, providing detailed protocols and resources to empower researchers in leveraging these powerful tools for advanced genomic studies.

Historical Progression and Key Methodological Advances

The foundation of single-cell transcriptomic analysis was laid approximately two decades ago with pioneering work using PCR for exponential amplification of single-cell cDNAs [24]. A significant breakthrough came in 2009 with the first reported scRNA-seq application at the 4-cell blastomere stage, demonstrating the feasibility of profiling gene expression at single-cell resolution [11]. The period from 2011 to 2015 witnessed rapid diversification of scRNA-seq protocols, with the introduction of both plate-based and early droplet-based methods that established the core principles of cellular barcoding and Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) incorporation [14].

Table 1: Key Milestones in scRNA-seq Technology Development

| Year | Milestone Achievement | Protocol/Technology | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | First scRNA-seq application | Blastomere stage sequencing [11] | Demonstrated feasibility of single-cell transcriptomics |

| 2011-2013 | Early protocol development | STRT-seq, Smart-seq, Quartz-seq [14] | Established basic workflow for single-cell analysis |

| 2014 | First multiplexed method | Smart-seq2 [11] | Improved sensitivity and full-length transcript coverage |

| 2015 | High-throughput droplet methods | Drop-Seq, InDrop [14] | Enabled massive parallelization, reduced cost per cell |

| 2017-2018 | Enhanced sensitivity and throughput | 10X Chromium V2/V3, Quartz-seq2 [14] | Improved gene detection per cell, standardized workflows |

| 2020-2022 | Multi-omics integration & improved resolution | Smart-seq3, scDART, Flex protocol [26] [14] | Enabled integrated analysis with epigenomics, sample multiplexing |

The introduction of droplet-based technologies around 2015, particularly Drop-Seq and InDrop, represented a watershed moment by dramatically increasing throughput while reducing costs [14]. This period also saw the refinement of full-length transcript protocols like Smart-seq2, which offered superior sensitivity for detecting more expressed genes compared to earlier methods [11]. The subsequent commercial development of platforms such as 10X Genomics Chromium further standardized and democratized high-throughput scRNA-seq, making the technology accessible to a broader research community [25].

Comparative Analysis of scRNA-seq Protocols

The landscape of scRNA-seq protocols has diversified significantly, with each method offering distinct advantages and limitations tailored to different research applications. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate experimental approach.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Representative scRNA-seq Protocols

| Protocol | Throughput | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Cost per Cell (USD) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-seq2 | Low-throughput (1-1,000 cells) | Full-length | No | $1.50-$2.50 [14] | Alternative splicing, mutation detection |

| CEL-seq2 | Medium throughput (100-1,000 cells) | 3' end | Yes (6bp) | $0.30-$0.50 [14] | Standard gene expression profiling |

| MATQ-seq | Medium throughput (100-1,000 cells) | Full-length | Yes | $0.40-$0.60 [14] | Detection of low-abundance genes |

| 10X Chromium | High-throughput (>10,000 cells) | 3' end | Yes (10-12bp) | ~$0.50 [14] | Large-scale atlas projects, rare cell identification |

| Drop-Seq | High-throughput (1,000-10,000 cells) | 3' end | Yes (8bp) | $0.10-$0.20 [14] | Cost-effective large-scale studies |

| Split-seq | High-throughput (>10,000 cells) | 3' end | Yes (10bp) | ~$0.01 [14] | Extreme scalability, combinatorial indexing |

The choice between full-length and 3'-end sequencing protocols represents a fundamental trade-off between transcriptomic information content and cellular throughput. Full-length methods like Smart-seq2 and MATQ-seq excel in applications requiring comprehensive transcript characterization, such as isoform usage analysis, allelic expression detection, and identification of RNA editing events [11]. In contrast, 3'-end methods like 10X Chromium and Drop-Seq prioritize scalability, enabling profiling of tens of thousands of cells in a single experiment, which is particularly valuable for comprehensive characterization of complex tissues and identification of rare cell populations [11] [25].

Diagram 1: Core scRNA-seq Experimental Workflow

Essential Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Cell Isolation

The initial stage of scRNA-seq involves extracting viable individual cells from the tissue of interest. The selection of an appropriate isolation strategy is critical for data quality and has evolved significantly with technological advancements.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Enables selection of specific cell types using fluorescent markers but requires substantial starting material (>10,000 cells) and specific antibodies [25]. This method is ideal for targeted studies of predefined populations.

Microfluidic Droplet-Based Systems: Technologies like 10X Genomics Chromium offer low sample consumption, precise fluid control, and high throughput, making them suitable for large-scale exploratory studies [25]. These systems typically require >1,000 cells as input.

Combinatorial Indexing Methods: Protocols like split-pool sci-RNA-seq and SPLiT-seq use combinatorial barcoding to label individual cells without requiring physical isolation [11]. These approaches enable extreme scalability (profiling up to millions of cells) and eliminate the need for expensive microfluidic devices.

Nuclear RNA Sequencing (snRNA-seq): An alternative approach when tissue dissociation is challenging, or when working with frozen samples or fragile cells [11]. This method has been successfully applied in large-scale atlas projects like GTEx [27].

Molecular Barcoding and Library Preparation

Following cell isolation, scRNA-seq protocols incorporate sophisticated barcoding strategies to enable multiplexing and accurate quantification:

Cell Barcodes: Short DNA sequences (typically 6-19bp) that uniquely label each cell, allowing pooling of multiple cells during library preparation and sequencing while maintaining the ability to deconvolve individual cell profiles [14].

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Short random nucleotide sequences (typically 6-12bp) that tag individual mRNA molecules during reverse transcription, enabling precise quantification by correcting for amplification biases [11]. Protocols including CEL-seq2, MARS-seq, Drop-Seq, and 10X Chromium have incorporated UMIs to enhance quantitative accuracy [11].

Amplification Methods: Current protocols primarily use either polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or in vitro transcription (IVT) for cDNA amplification. PCR-based methods (e.g., Smart-seq2, Drop-Seq, 10X Genomics) offer non-linear amplification, while IVT-based approaches (e.g., CEL-seq2, MARS-seq) provide linear amplification [11].

Quality Control and Cell Filtering

Rigorous quality control is essential for generating reliable scRNA-seq data. The following metrics and methods represent current best practices:

Cell Quality Assessment: Filtering based on three primary metrics - the number of genes detected per cell, total read counts per cell, and the percentage of mitochondrial genes. Cells with low gene counts, low reads, or high mitochondrial percentage typically indicate poor quality or dying cells [28].

Doublet Identification: Critical in droplet-based methods where multiple cells can be captured in a single droplet. Tools like Scrublet and scDblFinder can identify these doublets, whose RNA mixtures can create artifactual cell types in downstream analysis [13] [29].

Mitochondrial Contamination: High percentages of mitochondrial reads often indicate compromised cell integrity due to broken plasma and mitochondrial membranes [28]. Setting appropriate thresholds for mitochondrial gene percentage is essential for filtering low-quality cells.

Automated Quality Control: Platforms like Cell Ranger (10X Genomics) and Seurat provide standardized pipelines for initial quality assessment, while tools like the Loupe Browser offer intuitive visual interfaces for quality control with real-time feedback on cell quality [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Beads | Cell-specific mRNA capture and barcoding | Poly(T)-primed beads in droplet systems (e.g., 10X Chromium) capture polyadenylated RNA [11] |

| UMI Oligonucleotides | Molecular counting and amplification bias correction | Incorporated during reverse transcription; essential for accurate quantification [11] |

| Template Switching Oligos | cDNA amplification | Exploit terminal transferase activity of reverse transcriptase for full-length cDNA synthesis [11] |

| Cell Barcoding Kits | Sample multiplexing | Flex protocol from 10X Genomics uses gene-specific barcodes for sample multiplexing before pooling [13] |

| Viability Stains | Cell quality assessment | Propidium iodide or similar stains for selecting viable cells during FACS sorting |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | RNA degradation prevention | Critical during cell lysis and RNA capture to maintain RNA integrity |

| Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis | Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) RT common for template-switching protocols [11] |

Data Analysis Pipelines and Computational Tools

The computational analysis of scRNA-seq data presents unique challenges due to its high-dimensional, sparse, and noisy nature [11]. A standardized workflow has emerged to transform raw sequencing data into biological insights:

Diagram 2: scRNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow

Preprocessing and Quality Control: Initial processing involves demultiplexing by cell barcodes and UMIs, followed by alignment to reference genomes using tools like STAR or Cell Ranger [29]. Quality control then filters low-quality cells based on metrics like UMI counts, detected genes, and mitochondrial percentage [28].

Normalization and Batch Correction: Techniques like SCTransform or LogNormalize adjust for sequencing depth variations, while tools like Harmony or Seurat's CCA mitigate batch effects arising from technical variations between experiments [29].

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) followed by non-linear methods like t-SNE or UMAP project high-dimensional data into two or three dimensions for visualization [29]. Clustering algorithms (typically Louvain community detection) then identify distinct cell subpopulations [29].

Cell Type Annotation and Advanced Analysis: Marker gene analysis using databases like CellMarker or PanglaoDB assigns biological identities to clusters [29]. Advanced analyses include pseudotime trajectory inference (Monocle, Slingshot) to reconstruct developmental processes, and differential expression testing to identify genes defining specific cell states [25].

Applications and Future Perspectives

The evolution of scRNA-seq capabilities has enabled transformative applications across biomedical research:

Developmental Biology: Mapping embryonic lineage diversification and organogenesis, as demonstrated by the integrated human embryo reference atlas combining data from zygotes to gastrulas [25].

Disease Mechanisms: Dissecting tumor microenvironments to reveal cellular heterogeneity and immune interactions in cancers like glioblastoma, where scRNA-seq identified abnormal enrichment of plasma cells maintaining cancer stem cells [25].

Precision Medicine: Linking genetic variations to affected cell types in rare diseases and identifying therapeutic targets such as tumor-specific neoantigens [25].

Multi-Omics Integration: Emerging methods like scDART enable integrative analysis of scRNA-seq with scATAC-seq data, simultaneously learning cross-modality relationships and preserving continuous cell trajectories without requiring pre-defined gene activity matrices [26].

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing spatial context through spatial transcriptomics, improving computational methods for biological interpretation, and further reducing costs to enable even larger-scale studies. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly uncover new dimensions of cellular heterogeneity and function, further advancing our understanding of biology and disease.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of gene expression at the level of individual cells. A critical innovation underpinning the accuracy and quantitativeness of modern scRNA-seq protocols is the implementation of combinatorial barcoding strategies. This application note details the foundational principles of cellular barcoding and Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), which together facilitate the precise quantification of transcript abundance by tracing sequencing reads back to their cell of origin while correcting for amplification biases. We provide a comprehensive overview of the molecular biology involved, summarized quantitative data from key studies, detailed experimental protocols for a standard droplet-based method, and a curated list of essential research reagents. Framed within broader scRNA-seq research, this document serves as a technical guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement or understand these crucial techniques for accurate cellular heterogeneity dissection.

The fundamental challenge in single-cell transcriptomics stems from the minute starting material of a single cell, which contains only picograms of total RNA. To make this material compatible with next-generation sequencing platforms, an amplification step—typically via Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) or In Vitro Transcription (IVT)—is required. This amplification is an imprecise process where some molecules are amplified more than others, introducing significant technical noise and bias that can obscure the true biological signal [12] [30]. Without a method to account for this, a read count matrix would reflect a combination of true transcript abundance and technical amplification bias, leading to inaccurate gene expression measurements.

Cellular barcoding and UMIs were developed to resolve this issue. The core principle involves tagging each molecule with unique oligonucleotide sequences at the very beginning of the workflow. A cellular barcode (CB) is a short DNA sequence that is unique to each individual cell, allowing all reads derived from that cell to be tagged and computationally grouped after multiplexed sequencing. A Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) is a random oligonucleotide sequence that is added to each individual mRNA molecule during the reverse transcription step. The UMI uniquely labels each original transcript, enabling bioinformatic pipelines to count the number of distinct UMIs mapped to a gene rather than the total number of reads, thereby correcting for amplification duplicates [30] [31] [11]. This combination transforms scRNA-seq from a qualitative to a robustly quantitative tool.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Foundations

The Anatomy of a Barcoded Read

In standard 3' end-counting, droplet-based protocols like CEL-Seq2, 10x Genomics, and Drop-seq, the structure of the sequenced reads is highly organized to incorporate these barcodes [30] [32]. The process typically involves paired-end sequencing.

- Read 1 (Barcoding Read): This read is dedicated to barcode information. It typically contains, in sequence, the Cellular Barcode (CB), which identifies the cell of origin, and the Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI), which tags the individual molecule. It often ends with a poly(dT) sequence that hybridizes to the poly(A) tail of the mRNA, confirming the molecule's orientation.

- Read 2 (Transcript Read): This read sequences the actual cDNA derived from the 3' end of the transcript, which is aligned to a reference genome to identify the corresponding gene.

Table 1: Key Components of a Barcoded scRNA-Seq Read

| Component | Description | Typical Length (bp) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Barcode (CB) | A fixed, platform-specific sequence | 8-16 bp [32] | Demultiplexing; assigning reads to individual cells |

| Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) | A random nucleotide sequence | 6-12 bp [32] | Correcting for PCR amplification bias; counting original molecules |

| Transcript Sequence | cDNA from the 3' or 5' end of the mRNA | Variable (e.g., 50-100 bp) | Gene identification |

How UMIs Enable Accurate Quantification: A Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how UMIs correct amplification bias to reveal true transcript counts.

The power of this method is demonstrated by comparing quantification with and without UMIs [30]. In a scenario where two transcripts from Gene Red and two from Gene Blue are amplified, amplification bias may result in 6 and 3 reads, respectively. A naive count would incorrectly suggest Gene Red has twice the expression of Gene Blue. By grouping reads by their gene and UMI, and counting only unique UMIs, the true count of two transcripts per gene is revealed.

Statistical Evidence for UMI Efficacy

The quantitative advantage of UMI-counting over read-counting is not just theoretical but has been rigorously established. A key study systematically compared the statistical distributions of UMI counts versus read counts using the same datasets. The research employed a backward model selection strategy to determine the best-fitting model among Poisson, Negative Binomial (NB), and Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) distributions [33].

Table 2: Model Selection and Goodness-of-Fit for UMI vs. Read Counts [33]

| Quantification Scheme | Dataset | Genes Preferring ZINB over NB (FDR<0.05) | Genes Adequately Fitted by Poisson (FDR>0.05) | Genes Rejecting NB Goodness-of-Fit (FDR<0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UMI Counts | CEL-Seq2/C1 | 0% | 84.0% | 0.4% |

| Read Counts | CEL-Seq2/C1 | 9.4% | 9.5% | 35.3% |

| UMI Counts | MARS-Seq | 0% | 39.4% | 0% |

| Read Counts | MARS-Seq | 34.5% | 2.4% | 1.1% |

The results are clear: while read counts often require complex ZINB models to account for excess zeros (dropouts), UMI counts are well-approximated by the simpler Negative Binomial model, and a significant proportion even fit the Poisson model. This confirms that UMI counting effectively simplifies the underlying data structure by mitigating technical artifacts, making it a more robust foundation for differential expression analysis [33].

Detailed Protocol: CEL-Seq2 Workflow for Droplet-Based scRNA-Seq

The following section provides a detailed methodology for a typical plate-based or droplet-based protocol utilizing UMIs, such as CEL-Seq2 [30].

Reagents and Equipment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Barcoded Beads | Silica or hydrogel beads coated with oligo(dT) primers containing the Cell Barcode (CB) and UMI. Essential for partitioning and labeling in droplet-based systems. |

| Reverse Transcriptase (e.g., Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV)) | Enzyme to convert single-cell mRNA into cDNA. Its template-switching activity is exploited in some protocols for efficient cDNA synthesis. |

| Template Switching Oligo (TSO) | An oligonucleotide that binds to the cDNA during reverse transcription, providing a universal primer binding site for subsequent amplification. |

| Nucleotides (dNTPs) | Building blocks for cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification. |

| PCR Reagents | Enzymes (Taq polymerase), buffers, and primers for amplifying the barcoded cDNA library to generate sufficient mass for sequencing. |

| Magnetic Beads for SPRI Clean-up | Used for size selection and purification of the cDNA and final sequencing library, removing enzymes, primers, and short fragments. |

| Library Quantification Kit (e.g., qPCR-based) | For accurate quantification of the final library concentration to ensure optimal sequencing loading. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Single-Cell Suspension Preparation:

- Prepare a high-viability (>90%) single-cell suspension from your tissue or cell culture using appropriate enzymatic and/or mechanical dissociation methods. Keep the cells on ice to minimize stress-induced transcriptional changes [12] [34].

- Resuspend cells at an optimal concentration in a compatible buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.04% BSA).

Single-Cell Partitioning and Barcoding:

- For droplet-based systems: Co-flow the single-cell suspension and the barcoded bead suspension within a microfluidic chip to encapsulate them into nanoliter-scale droplets. Each droplet ideally contains one cell and one bead.

- For plate-based systems: Use FACS to sort single cells into the wells of a 96- or 384-well plate that has been pre-loaded with lyis buffer and unique barcoded primers.

Cell Lysis and Reverse Transcription:

- Within each droplet or well, the cell is lysed, releasing its mRNA.

- The poly(A) mRNA hybridizes to the poly(dT) primer on the bead/well. The reverse transcriptase enzyme is activated, synthesizing first-strand cDNA. Critically, during this step, each cDNA molecule is tagged with the well-/bead-specific CB and a random UMI [31] [11].

cDNA Amplification and Library Construction:

- Break the droplets (if droplet-based) and pool the barcoded cDNA. For plate-based systems, the contents are pooled after RT.

- Amplify the pooled cDNA using PCR. The primers used are designed to target the constant adapter sequences added during RT.

- Purify the amplified cDNA using magnetic beads.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Fragment the amplified cDNA (if necessary) and ligate sequencing adapters to create the final sequencing library.

- Perform a final clean-up and quality control check (e.g., Bioanalyzer) on the library.

- Sequence the library on an Illumina platform using a paired-end run, where Read 1 is designed to sequence the CB and UMI, and Read 2 sequences the cDNA transcript.

Bioinformatic Processing Workflow

The raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) must be processed to generate a cell-by-gene count matrix. The following workflow is typically implemented using tools like STARsolo, Cell Ranger, or UMI-tools [32].

Key bioinformatic steps include:

- Barcode Processing: Cellular barcodes are matched against a whitelist of valid barcodes, allowing for a small number of mismatches (e.g., 1) to correct for sequencing errors [32].

- UMI Deduplication: This is the core quantification step. Algorithms (e.g., "directional" in UMI-tools) collapse UMIs that are nearly identical, accounting for potential sequencing errors, and count only one unique UMI per original molecule [32].

- Cell Calling: Barcodes associated with a significantly high number of UMIs are classified as cells, while those with very few are considered background noise or empty droplets.

Cellular barcoding and Unique Molecular Identifiers are not merely incremental improvements but foundational technologies that have endowed single-cell RNA sequencing with its quantitative power. By enabling precise assignment of sequencing reads to their cell of origin and, more importantly, by correcting for the stochastic biases introduced during cDNA amplification, they allow researchers to discern true biological heterogeneity from technical noise. The statistical evidence confirms that UMI-count data conforms to more tractable models, thereby increasing the reliability of downstream analyses like differential expression and cell population identification. As the field progresses towards sequencing millions of cells and integrating multi-omics modalities, the principles of combinatorial barcoding established here will continue to be the bedrock of accurate biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Navigating the scRNA-seq Landscape: Protocol Selection for Specific Research Applications

{ARTICLE CONTENT START}

Comparative Analysis of Major scRNA-seq Platforms: 10x Genomics, Parse Biosciences, and More

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed biomedical research by enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity, identification of novel cell types, and delineation of complex developmental trajectories that are obscured in bulk tissue analyses [35] [36]. The rapid evolution of this technology has yielded several commercial platforms, each with distinct methodologies and performance characteristics. This Application Note provides a detailed comparative analysis of two leading high-throughput platforms—10x Genomics Chromium and Parse Biosciences Evercode—and touches upon the BD Rhapsody system. Framed within a broader thesis on single-cell protocols, this document is designed to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal platform based on their specific experimental requirements, sample type, and budgetary constraints. We summarize quantitative performance data from recent benchmark studies, provide detailed experimental protocols, and visualize core workflows to facilitate informed experimental design and implementation.

The foundational technologies for partitioning and barcoding single cells differ significantly between the major platforms, leading to distinct advantages and limitations.

10x Genomics Chromium employs a droplet-based microfluidics system. In this approach, individual cells are co-encapsulated with barcoded gel beads in nanoliter-scale aqueous droplets, forming Gel Bead-in-Emulsions (GEMs) [35] [36]. Within each GEM, cell lysis occurs, and the released mRNA transcripts are captured by oligo(dT) primers on the beads. These primers contain unique cell barcodes and Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias [35]. This system is characterized by its high cell capture efficiency and standardized, automated workflow.

Parse Biosciences Evercode utilizes a split-pool combinatorial barcoding technique that is entirely instrument-free [37] [38] [39]. Cells are first fixed and permeabilized, making them their own reaction vessels. They then undergo multiple rounds of barcoding in standard well plates: cells are distributed into a plate for the first barcoding round, pooled, and then re-distributed into new plates for subsequent rounds. This process generates a vast combinatorial library of barcodes, uniquely labeling each cell's transcriptome [38] [39]. A key advantage is the scalability to over 1 million cells and the flexibility to process samples collected at different time points.

BD Rhapsody is a microwell-based system. Single cells and barcoded magnetic beads are randomly deposited into an array of picoliter wells via gravity. The beads, which are coated with primers containing cell labels and UMIs, then capture the mRNA from the lysed cells in each well [35]. Like the Parse platform, it avoids the need for specialized microfluidic equipment for cell partitioning.

Figure 1: Core scRNA-seq platform workflows. GEMs: Gel Bead-in-Emulsions; RT: Reverse Transcription.

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Comparison

Recent independent studies using mouse thymus and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) provide critical, data-driven insights into the performance of 10x Genomics and Parse Biosciences platforms.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics from Benchmark Studies

| Metric | 10x Genomics Chromium | Parse Biosciences Evercode | Context / Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Recovery Efficiency | ~53% - 56.5% [38] [39] | ~27% - 54.4% [38] [39] | Higher 10x efficiency is crucial for rare or low-input samples. Parse shows higher variability [38]. |

| Gene Detection per Cell | Median ~1,900 genes/cell (H1: 1,886; H2: 1,984) [39] | Median ~2,300 genes/cell (H1: 2,319; H2: 2,283) [39] | Parse detects ~1.2x more genes, potentially revealing finer biological details [38] [39]. |

| Sensitivity & Specificity | Lower technical variability; more precise biological state annotation in thymocytes [38]. | Detects nearly twice the total unique genes; identifies a distinct gene set [38]. | 10x may be better for complex cellular states; Parse for maximal gene discovery. |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Requires cell hashing with antibodies for sample multiplexing [35]. | Native multiplexing for 1-96 samples in a single run without hashtags [38] [39]. | Parse simplifies large, multi-sample studies and reduces batch effects. |

| Sequencing Efficiency | High fraction of valid barcodes (~98%); higher duplicate rate (50-56%) [39]. | Lower fraction of valid barcodes (~85%); lower duplicate rate (35-38%) [39]. | 10x uses sequencing depth more efficiently for exonic reads. |

| Workflow Flexibility | Requires proprietary microfluidics controller; fresh cells typically preferred. | No instrument; uses standard lab equipment. Fixation enables storage for months [37] [40] [41]. | Parse is ideal for longitudinal studies, large collaborations, or labs avoiding capital equipment. |

The choice between platforms involves trade-offs. A 2024 study on mouse thymocytes concluded that while Parse detected nearly twice the number of genes, the 10x data exhibited lower technical variability and more precise annotation of biological states in this complex immune tissue [38]. Conversely, a study on human PBMCs confirmed Parse's higher gene detection sensitivity, which can be critical for identifying rare cell types and low-abundance transcripts [39].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Platform Selection

Successful scRNA-seq begins with high-quality single-cell suspensions. Cell viability should exceed 85%, and concentrations must be optimized for each platform (e.g., 700–1,200 cells/μL for 10x Genomics) [36]. For difficult-to-obtain or time-course samples, Parse's fixation protocol (allowing storage for up to 6 months) is a significant advantage [40] [41]. Researchers must decide between the standardized, high-efficiency 10x workflow and the flexible, scalable, instrument-free Parse workflow based on their experimental goals.

Library Preparation Workflows

10x Genomics Chromium Protocol (3' Gene Expression)

- Prepare Master Mix: Combine cells, RT reagents, and partitioning oil.

- Generate GEMs: Load the master mix, gel beads, and partitioning oil onto a Chromium chip. The controller generates single-cell GEMs.

- Reverse Transcription: Perform incubation for cell lysis, mRNA capture, and reverse transcription inside the GEMs. Each cDNA molecule is tagged with a cell barcode and UMI.

- Break Emulsions: Purify cDNA from the pooled GEMs.

- cDNA Amplification: Perform PCR to amplify the full-length cDNA.

- Library Construction: Fragment and size-select the amplified cDNA, then add sample indices and adapters for sequencing via PCR.

- Quality Control and Sequencing: Quantify libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) [35] [36].

Parse Biosciences Evercode Protocol (Whole Transcriptome)

- Cell Fixation and Permeabilization: Incubate cells with fixative and permeabilization buffers. Fixed cells can be stored for later use.

- Reverse Transcription (Round 1): Distribute cells into a 96-well plate containing well-specific barcodes for in-cell reverse transcription.

- Pool and Split (Rounds 2-4): Pool all cells, then re-distribute them into new plates for subsequent rounds of barcoding. This split-pool method combinatorially labels transcripts.

- cDNA Clean-up and Amplification: After the final barcoding round, pool cells and purify the cDNA. Amplify the cDNA via PCR.

- Library Construction and Indexing: Fragment the cDNA and add platform-compatible Illumina adapters and sample indices via PCR.

- Quality Control and Sequencing: Quantify libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform [38] [39] [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Platform Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Beads | Deliver oligos with cell barcodes, UMIs, and poly(dT) for mRNA capture. | Gel Beads (10x) [35], Magnetic Beads (BD Rhapsody) [35]. |

| Fixation Buffer | Preserves cellular RNA content at the time of collection, enabling sample storage. | Parse Evercode Fixation Buffer [40] [41]. |

| Combinatorial Barcoding Plates | 96-well plates pre-loaded with well-specific barcodes for split-pool labeling. | Parse Evercode kits [38]. |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Oligo-conjugated antibodies for sample multiplexing in droplet-based platforms. | BioLegend TotalSeq antibodies [35]. |

| Partitioning Oil & Microfluidics Chips | Generate stable, nanoliter-scale droplets for single-cell isolation. | 10x Genomics Chip & Partitioning Oil [36]. |

| Reverse Transcription & PCR Kits | Enzymatic mixes for cDNA synthesis and amplification, optimized for each platform. | Included in all commercial kit chemistries. |

Downstream Data Analysis and Bioinformatics Pipelines

Following sequencing, raw data must be processed to generate gene expression matrices. The standard pipeline involves demultiplexing, barcode/UMI counting, alignment, and gene counting. For 10x Genomics data, Cell Ranger is the dedicated preprocessing software that aligns reads to a reference genome and generates a feature-barcode matrix [42]. For Parse data, the split-pipe pipeline performs demultiplexing based on the combinatorial barcodes [38].

Subsequent analysis is typically performed in R or Python environments. Key steps include:

- Quality Control: Filtering cells based on detected genes, UMI counts, and mitochondrial RNA percentage [38].

- Normalization and Batch Correction: Using tools like Harmony to integrate data from multiple samples or batches [42].

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) followed by graph-based clustering on Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plots to identify cell populations [43].

- Cell Type Annotation: Leveraging reference atlases or marker genes to label clusters. Newer platforms like Nygen and BBrowserX offer AI-powered automated annotation [43].

- Advanced Analysis: Tools like Velocyto (RNA velocity), Monocle 3 (trajectory inference), and Squidpy (spatial analysis) can extract deeper biological insights [42].

The scRNA-seq landscape offers powerful options, each with distinct strengths. 10x Genomics Chromium is the established leader, offering a robust, standardized workflow with high cell capture efficiency and low technical variability, making it suitable for a wide range of applications, particularly where precise annotation of cell states is critical [38] [36]. Parse Biosciences Evercode provides unparalleled scalability and flexibility, with superior gene detection sensitivity and native multiplexing, ideal for large-scale studies, longitudinal experiments, and labs seeking to avoid capital investment in proprietary instruments [37] [38] [39]. BD Rhapsody offers a well-based alternative that facilitates targeted transcriptomic panels [35].

The decision ultimately hinges on the specific research question. For projects requiring the highest data consistency for complex tissues or clinical samples, 10x Genomics remains a gold standard. For ambitious atlas-level projects, time-course experiments, or studies with limited budgets for hardware, Parse Biosciences presents a compelling and powerful alternative. As the field progresses, integration with multi-omics modalities and spatial transcriptomics will further enhance the power of single-cell analysis across all platforms.

{ARTICLE CONTENT END}

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling the investigation of gene expression profiles at the level of individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity that is often masked in bulk analysis [2] [24]. The selection of an appropriate scRNA-seq protocol is a critical strategic decision that directly determines the biological questions a researcher can address. These protocols primarily fall into two categories: those capturing full-length transcripts and those performing 3' or 5' end-counting [2] [44]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these approaches, detailing their respective methodologies, strengths, and limitations to guide researchers in aligning their protocol selection with specific research objectives.

The fundamental difference between these protocol categories lies in the amount of transcript information captured and the consequent analytical applications they support.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major scRNA-seq Protocol Types

| Feature | Full-Length Transcript Protocols | 3' or 5' End-Counting Protocols |