Standardized Protocols for Reproducible Spheroids: A Guide for High-Throughput Screening and Disease Modeling

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing standardized and reproducible spheroid models.

Standardized Protocols for Reproducible Spheroids: A Guide for High-Throughput Screening and Disease Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing standardized and reproducible spheroid models. It covers the foundational principles of 3D cell culture, detailing optimized protocols for generating uniform spheroids using various platforms such as ultra-low attachment plates, hanging drop methods, and micro-molded scaffolds. The content explores critical parameters for troubleshooting, including initial cell density, viability assessment, and matrix embedding techniques. Furthermore, it validates these models through direct comparisons with traditional 2D cultures and in vivo systems, highlighting their enhanced physiological relevance for anti-cancer drug screening, invasion assays, and personalized medicine applications. The synthesized protocols and best practices aim to bridge the gap between simple in vitro models and complex in vivo environments, facilitating more predictive pre-clinical research.

The Critical Role of Spheroids in Modern Biomedical Research

Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture, where cells grow in a single layer on flat plastic surfaces, has been a workhorse of biological research for decades [1]. However, its limitations in mimicking the complex architecture of human tissues are increasingly apparent, particularly in drug discovery where approximately 90% of compounds that pass 2D tests fail in clinical trials [1] [2]. The transition to three-dimensional (3D) spheroid models represents a paradigm shift toward more physiologically relevant systems. Spheroids are defined as three-dimensional cellular aggregates that self-assemble into structures that better recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment [3]. This guide provides a technical framework for understanding the critical differences between 2D and spheroid cultures, with standardized protocols and troubleshooting advice to ensure reproducible research outcomes.

Core Differences: A Structural and Functional Comparison

Structural Architecture

The fundamental architectural differences between 2D monolayers and 3D spheroids create dramatically different microenvironments for cells.

- 2D Architecture: In traditional culture, cells are forced to adopt flattened, unnatural morphologies on rigid plastic surfaces. They exhibit limited cell-cell interactions and no spatial organization, with uniform exposure to nutrients, oxygen, and drugs [1] [4].

- 3D Spheroid Architecture: Spheroids develop a complex 3D structure characterized by distinct cellular zones, mirroring the architecture of avascular tumors or microtissues [3] [4]:

- Proliferative Outer Layer: Composed of rapidly dividing cells with direct access to oxygen and nutrients.

- Quiescent Intermediate Layer: Contains dormant, senescent cells due to limited nutrient availability.

- Hypoxic/Apoptotic Core: Features necrotic or apoptotic cells resulting from severe oxygen and nutrient deprivation, which also mimics a key feature of solid tumors.

Functional Consequences

These structural differences translate directly to critical functional variations that impact experimental outcomes.

- Gene Expression and Protein Profiles: Cells in spheroids demonstrate gene expression profiles that are more representative of in vivo conditions compared to 2D cultures. For instance, studies show upregulation of genes related to hypoxia, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and stemness in 3D models [4].

- Drug Response and Resistance: Spheroids develop gradients of drug penetration and exhibit increased drug resistance, providing a more accurate platform for therapeutic screening. The dense structure and presence of quiescent cells create physical and biological barriers that are absent in 2D [1] [3].

- Metabolic Activity: Spheroids display distinct metabolic patterns, including elevated per-cell glucose consumption and increased lactate production (Warburg effect) under glucose restriction, highlighting more metabolically active cells compared to 2D cultures [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key Functional Metrics in 2D vs. 3D Cultures

| Functional Parameter | 2D Culture Findings | 3D Spheroid Findings | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Proliferation | High, exponential growth until confluence [2]. | Reduced proliferation rates due to diffusion limitations and heterogeneous zones [2]. | U251-MG glioblastoma & A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells [2]. |

| Glucose Dependence | Critical for survival; proliferation stops completely under glucose deprivation [2]. | Cells survive longer under glucose deprivation by activating alternative metabolic pathways [2]. | U251-MG glioblastoma & A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells [2]. |

| Lactate Production | Lower per-cell lactate production [2]. | Higher lactate production, indicating an enhanced Warburg effect [2]. | U251-MG glioblastoma & A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells [2]. |

| Drug Penetration | Uniform exposure, often leading to overestimation of drug efficacy [1]. | Limited and gradient-dependent penetration, modeling in vivo diffusion barriers [1] [3]. | Various cancer cell lines; a key reason for clinical trial failures [1]. |

| Gene Expression | Altered, less representative of in vivo profiles [4]. | Better fidelity; unique profiles for EMT, hypoxia, and stemness markers [4]. | Lung, breast, and colorectal cancer cell models [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Success in spheroid culture relies on specialized materials that prevent cell adhesion and promote aggregation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spheroid Culture

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates | Plates with a engineered surface that inhibits cell attachment, forcing cells to aggregate into a single spheroid per well. Prevents satellite colony formation [5]. | The primary method for consistent, scaffold-free spheroid formation (e.g., Nunclon Sphera plates) [5]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogels | Natural or synthetic scaffolds (e.g., Matrigel, collagen) that provide a 3D microenvironment mimicking in vivo conditions, supporting cell-matrix interactions [2] [4]. | Used in matrix-based 3D cultures and tumor-on-chip models to study invasion and organization [2]. |

| Wide-Bore Pipette Tips | Tips with a large orifice to prevent shear stress and physical damage when transferring mature spheroids [5]. | Essential for aspirating and moving spheroids without disrupting their structure for downstream analysis [5]. |

| Tissue Clearing Reagents | Chemical solutions that render large, dense spheroids transparent for deep and high-resolution imaging [5]. | Enables fluorescent imaging of structures up to 1000 µm deep within a spheroid [5]. |

| 3D-Optimized Viability Dyes | Cell health assays (e.g., PrestoBlue, alamarBlue, caspase 3/7 probes) with modified protocols for better penetration into dense 3D structures [5]. | Requires higher dye concentrations or longer incubation times than 2D protocols (see Table 3) [5]. |

Standardized Workflow for Spheroid Formation

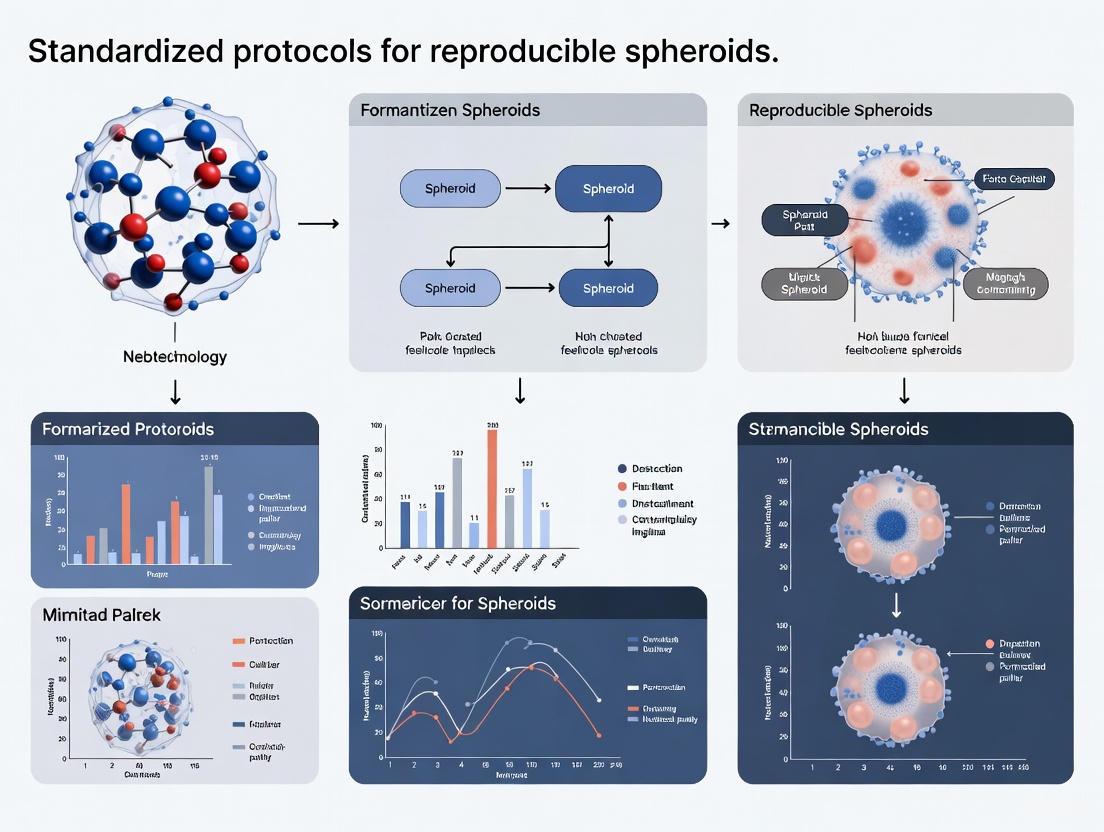

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, robust workflow for generating spheroids using ULA plates, integrating the centrifugation method to enhance consistency.

Protocol: Spheroid Formation by Centrifugation [6] [5]

- Cell Preparation: Harvest cells using standard trypsinization. Count cells and prepare a suspension at a concentration of 2x10⁶ cells/mL in complete medium. Tip: Seeding density controls final spheroid size.

- Dispensing: Pipette the cell suspension into each well of a 96-well round-bottom ULA plate. A typical volume is 150 µL/well.

- Centrifugation: Place the plate in a balanced centrifuge with a plate rotor. Spin at room temperature at 300 x g for 4 minutes. Tip: This step pellets cells to the well bottom, initiating uniform aggregation.

- Incubation and Maturation: Carefully transfer the plate to a 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator. Compact spheroids typically form within 24-72 hours. For long-term cultures (e.g., >5 days), perform half-media changes every 2-3 days by gently removing old media and adding fresh pre-warmed media without disturbing the spheroid.

Troubleshooting FAQs and Technical Guidance

Q1: How can I consistently grow uniform spheroids of a specific size? A: The most reliable method is to use ULA round-bottom plates and control the initial cell seeding density. Using a confined physical space like a round-bottom well ensures the formation of a single, central spheroid. Centrifuging the plate after seeding (150-300 x g for 3-5 minutes) significantly improves consistency by rapidly collecting all cells at the bottom of the well [6] [5].

Q2: My cell lines do not form compact spheroids. What can I do? A: Not all cell types form tight spheroids readily. If centrifugation is insufficient:

- Patience is key: Some cell lines require several days to form compact spheroids.

- Media refreshment: For slow-forming spheroids, replace half of the culture media with fresh media every 2-3 days to maintain nutrient levels and remove waste, but do so gently to avoid disruption [5].

Q3: How do I handle and perform media changes without damaging spheroids? A: Manual handling requires care.

- For media changes: Tilt the plate at a 45° angle. Slowly aspirate the old media from the surface, ensuring the pipette tip does not contact the spheroid at the bottom. Add new media by dispensing it gently against the side of the well.

- For transfer: Use wide-bore or wide-orifice pipette tips to prevent shearing or crushing the spheroid during pipetting [5].

Q4: Can I use my standard 2D cell viability and staining assays on spheroids? A: Yes, but protocols require significant optimization. The dense 3D structure impedes reagent penetration. Key adjustments include:

- Increasing reagent incubation times.

- Using higher concentrations of dyes and antibodies.

- Incorporating tissue-clearing reagents for immunostaining to enable deep imaging.

Table 3: Protocol Adjustments for Common Assays in 3D Spheroids [5]

| Assay / Reagent | 2D Protocol | 3D Spheroid Protocol | Reason for Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability (e.g., PrestoBlue) | Standard concentration, 30-60 min incubation. | May require longer incubation (e.g., 2+ hours) and occasional plate rotation. | To allow for full diffusion of the reagent into the spheroid core. |

| Apoptosis (Caspase 3/7) | 1X concentration, 30 min incubation. | Lower concentration (e.g., 1/3X) with longer incubation (e.g., 2 hours). | Prevents over-staining of the outer layer and allows detection in the interior. |

| Immunostaining | Standard antibody incubation (few hours). | Significantly longer incubation (often overnight) and the use of clearing kits. | Antibodies penetrate slowly; clearing reduces light scattering for better imaging. |

The transition from 2D culture to 3D spheroid models is more than a technical upgrade; it is a necessary step toward biologically relevant and predictive in vitro research. Spheroids, with their defined structural zones and resulting functional complexity—from gradient-driven metabolism to more accurate drug response profiles—offer a superior system for disease modeling, drug discovery, and personalized medicine. By adhering to standardized protocols like the ULA plate method and applying the troubleshooting solutions outlined herein, researchers can overcome initial technical hurdles and reliably generate high-quality data that better translates to clinical success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the core advantages of 3D models over traditional 2D cell cultures? 3D models, such as spheroids and organoids, offer a more physiologically relevant environment than 2D monolayers. They mimic the 3D architecture of human tissues, enabling critical cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, and facilitating the formation of physiological gradients (e.g., oxygen, nutrients, metabolic waste). This leads to more predictive data for drug efficacy, toxicity, and human-specific responses, ultimately reducing the reliance on animal models and improving the success rate of clinical translations [7] [8] [9].

How do 3D models improve drug discovery and development? In drug discovery, 3D models demonstrate superior predictive power. They more accurately replicate in vivo drug responses, including penetration, metabolism, and toxicity. For instance, 3D tumor spheroids can replicate patient-derived drug resistance mechanisms, helping to identify false positives or negatives earlier in the development process. This allows researchers to "fail faster" and focus resources on the most promising drug candidates [7] [10] [9].

What is the difference between a spheroid and an organoid? While both are common 3D culture formats, they have distinct characteristics. Spheroids are self-assembled, spherical aggregates of cells that can be derived from a wide range of cell types, including cell lines. They model basic tissue features like nutrient gradients and zonation. Organoids are more complex structures generated from stem cells that self-organize to replicate the functional and structural complexity of specific organs, making them powerful for disease modeling and personalized medicine [8] [9].

Why is standardization a significant challenge in 3D cell culture, and how is it being addressed? A major challenge is reproducibility, as protocol variability across labs leads to inconsistent spheroid morphology and behavior. Key variables include media composition, serum concentration, oxygen levels, and initial seeding density [11] [10]. In response, initiatives like the NIH's $87 million Standardized Organoid Modeling (SOM) Center are using AI-driven optimization and robotic automation to create validated, reproducible organoid protocols and samples [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Spheroid Size and Morphology

Inconsistent spheroid formation can compromise experimental reproducibility and data reliability.

Potential Cause & Solution: Initial Seeded Cell Number The initial cell number directly determines spheroid size. A study analyzing 32,000 spheroid images found that varying the seeding density (2000-6000 cells) led to significant differences in spheroid dimensions and growth kinetics. Establish and strictly adhere to an optimized seeding density for your specific cell type [10].

Potential Cause & Solution: Serum Concentration Serum concentration in the culture medium critically regulates spheroid density and architecture. Research shows that concentrations above 10% promote the formation of dense spheroids with distinct necrotic and proliferative zones, while serum-free conditions can cause spheroid shrinkage and reduced density [10]. Standardize the serum percentage in your media formulation.

Potential Cause & Solution: Culture Media Composition Variations in media components like glucose and calcium levels significantly impact spheroid growth and viability. For example, one study noted that RPMI 1640 medium resulted in significantly elevated cell death signals compared to other media [10]. Use a consistent, well-defined media formulation and avoid switching between different media types without re-optimization.

Issue: Poor Cell Viability in 3D Constructs

Unexpected cell death can occur in both encapsulated and bioprinted 3D cultures.

Potential Cause & Solution: Oxygen and Nutrient Gradients Oxygen tension is a pivotal factor. Cultures under 3% O₂ exhibited reduced spheroid size, decreased cell viability, and increased necrosis in the core [10]. In thicker constructs, nutrient diffusion can be limited. Consider using specialized culture plates, incorporating microfluidic perfusion systems, or leveraging bioprinting to create structures with microchannels to improve transport [8] [12].

Potential Cause & Solution: Crosslinking Process If using hydrogels or bioprinting, the crosslinking method can expose cells to harsh chemicals or physical stress. Varying the degree of crosslinking can also alter the mechanical properties of the matrix, affecting cell behavior. Optimize the crosslinking parameters (e.g., concentration, duration) for your specific material and cell type to ensure biocompatibility [12].

Potential Cause & Solution: Sample Thickness In encapsulated systems, samples thicker than 0.2 mm can lead to core necrosis due to diffusion limitations. If possible, reduce the thickness of the construct. As noted in the troubleshooting guide, bioprinting can help by allowing precise control over geometry and the integration of microchannels to enhance nutrient flow and waste removal [12].

Issue: High Variability in Drug Response Data

Unreliable drug screening results can stem from underlying inconsistencies in the 3D models themselves.

Root Cause Analysis: This issue is often a downstream effect of the problems described above. Inconsistent spheroid size, morphology, and viability directly impact drug penetration and cellular response, leading to highly variable IC50 values and other readouts [10].

Solution: Implement Rigorous Quality Control Before proceeding with drug testing, implement quality control checks. Use automated image analysis and AI-powered software to quantify key spheroid metrics (e.g., diameter, circularity, viability) and only use batches that meet predefined criteria for size and uniformity [7] [10]. The NIH SOM Center emphasizes such quality benchmarks for reliable research [11].

The following tables consolidate key experimental data from large-scale studies on factors affecting spheroid attributes.

Table 1: Impact of Culture Conditions on Spheroid Attributes [10]

| Experimental Variable | Condition | Observed Impact on Spheroids |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Level | 3% O₂ | Reduced dimensions (equivalentDiameter, volume), significant decrease in cell viability and ATP content, heightened signal in necrotic area. |

| Serum Concentration | 0.5% - 1% | Highest levels of cell death (fluorescence intensity per spheroid area). |

| 10% - 20% | Densest spheroid formation, distinct necrotic/quiescent/proliferative zones, stable ATP levels. | |

| Culture Medium | RPMI 1640 | Significantly elevated death signal intensity compared to other media. |

| DMEM/F12 | Lowest spheroid viability. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Spheroids

| Protocol Step | Key Parameter | Recommendation for Standardization |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Seeding | Initial Cell Number | Optimize and fix the cell number for each cell line (e.g., within 2000-6000 range); this is a primary determinant of final spheroid size [10]. |

| Media Formulation | Serum Percentage | Use concentrations ≥10% for dense, structured spheroids; document and maintain batch-to-batch consistency [10]. |

| Culture Environment | Oxygen Tension | Control and document oxygen levels (e.g., physioxic 3-5% O₂ for many tumor models) to manage gradients and necrosis [10]. |

| Quality Control | Imaging & Analysis | Use automated high-content imaging and AI-based analysis software (e.g., IN Carta Image Analysis Software) to quantify size, circularity, and viability for pre-screening before assays [7]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Tools for 3D Cell Culture Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Hydrogels (e.g., Alginate, Matrigel, Collagen) | Serve as scaffold-based systems to provide a 3D extracellular matrix (ECM) environment that supports cell growth and signaling [8] [9]. |

| Low-Adhesion / Microwell Plates | Enable scaffold-free spheroid formation by promoting cell aggregation in a controlled manner [8] [9]. |

| Specialized Culture Media | Formulations (e.g., DMEM, RPMI) are tailored for 3D cultures, with specific adjustments to components like glucose and calcium to support spheroid health [10] [13]. |

| Automated Imaging & Analysis Software | Systems like the ImageXpress HCS.ai and IN Carta Software are crucial for high-throughput, quantitative analysis of 3D model morphology and health [7]. |

| Microfluidic Devices (Organ-on-a-chip) | Provide precise control over the cellular microenvironment, enable perfusion, and allow for the modeling of complex tissue interfaces and fluid flow [7] [8]. |

Experimental Workflow and Variable Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the standardized workflow for creating reproducible spheroids and the complex relationships between key experimental variables.

Standardized Spheroid Workflow

Key Variables Affecting Drug Response

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Spheroid Formation

Q1: How can I consistently grow uniform spheroids to get repeatable results?

The most critical parameter for controlling spheroid size is adjusting the initial cell seeding density [14] [5]. Using cultureware that confines cells physically promotes the consistent formation of a single spheroid per well.

- Recommended Solution: Use 96-well ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates with U-bottom wells [14] [5] [15]. The hydrophilic polymer coating inhibits protein adsorption and cell attachment, forcing cells to aggregate into a single, central spheroid [5] [16]. This method is simple, affordable, and compatible with high-throughput screening (HTS) platforms.

- Troubleshooting Tip: If cells do not form compact spheroids, centrifuge the plate at a low speed (e.g., 150 x g for 5 minutes) after seeding to help cells quickly settle at the bottom of the wells. For some cell types, spheroid formation may take several days; during this time, replace 50% of the media with fresh media every 2-3 days to maintain culture health [5].

Q2: My cell lines are not forming tight spheroids. What can I do?

Not all cell types readily form compact spheroids. In addition to centrifugation, ensure you are using a high-quality low-attachment plate. The surface modification must be superb, as imperfections can cause cells to attach to the plastic instead of aggregating with each other [5]. Selecting a reputable manufacturer with expertise in surface modification is highly recommended for reproducibility.

Spheroid Culture and Handling

Q3: What are the best practices for handling spheroids during media changes and transfer?

Spheroids are delicate structures that require careful handling to prevent damage.

- Media Changes: Carefully tilt the microplate and slowly aspirate half of the supernatant from each well without touching the bottom. Gently dispense fresh, pre-warmed media along the well wall to avoid breaking the spheroids. For a complete media change, performing repeated half-media changes is often safer than a full change [5].

- Transferring Spheroids: Always use wide-bore or wide-orifice pipette tips to accommodate the diameter of the spheroids and prevent shear stress that can damage their structure during aspiration [5] [17].

Spheroid Analysis and Assaying

Q4: Can I use my standard 2D cell viability assays for spheroid cultures?

Yes, but standard protocols require optimization. The 3D, dense nature of spheroids impedes reagent penetration [5].

- Required Protocol Adjustments: You will typically need to increase the concentration of the detection reagent and/or extend the incubation time compared to 2D protocols [5]. For example, when using a caspase 3/7 reagent for apoptosis, one might reduce the concentration to one-third of the 2D recommendation but extend the incubation time from 30 minutes to 2 hours [5].

- General Tip: When adding reagents, avoid pipetting directly onto the spheroid. For larger, denser spheroids, gentle agitation during incubation can improve reagent penetration [5].

Q5: How do I successfully perform immunostaining on my spheroids?

Staining 3D spheroids is challenging due to limited penetration of stains and antibodies, high background signal, and the risk of damaging the structure [17].

- Optimized Staining Protocol:

- Fixation: Gently collect spheroids with a wide-bore tip and fix with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15-20 minutes at room temperature. Larger spheroids may require longer fixation [17].

- Permeabilization: Incubate with a permeabilization agent (e.g., 0.1-1.0% Triton X-100) for several hours at room temperature [17].

- Blocking: Incubate in a blocking buffer (e.g., 1% BSA with serum) for at least 1 hour to reduce non-specific antibody binding [17].

- Staining: Incubate with primary and secondary antibodies for 24-72 hours at 4°C to ensure deep penetration [17].

- Washing: Perform gentle, multi-step washing with PBS between each step. Low-speed centrifugation or allowing spheroids to settle by gravity can prevent loss [17].

- Imaging: Use mounting media designed for 3D imaging. For thick spheroids, confocal or light-sheet microscopy with Z-stacking is essential for complete visualization [17].

Quantitative Data for Spheroid Formation

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from a systematic study on glioma cell line spheroid formation, providing a reference for your experiments [14] [15] [18].

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Parameters for Glioma Spheroid Formation in ULA Plates

| Parameter | Finding | Experimental Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Seeding Density | 250 - 500 cells/well [14] | Fewer cells generally resulted in better growth than higher numbers. |

| Size Control | Linear correlation with initial cell number [14] [15] | Spheroid diameter and volume can be predictably controlled via seeding density. |

| Spheroid Structure | Outer layer of viable cells, inner core of dead cells [14] [15] | The size of the necrotic core varies by cell line and incubation time. |

| Culture Maintenance | Half-media change every 3-4 days [15] | Using 150 µL culture medium in a 96-well ULA plate. |

| Viability Staining | Propidium Iodide (PI) at 0.1 µg/mL [15] | Lower than standard 2D concentration to avoid toxicity for long-term monitoring. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Spheroid Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| ULA Plates | Promotes cell aggregation into single spheroids by inhibiting attachment. | High-throughput spheroid formation for drug screening [14] [5]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Scaffold to support complex 3D growth and differentiation. | Culturing patient-derived organoids [19] [20]. |

| Wide-Bore Pipette Tips | Handles spheroids without causing damage during transfer. | Aspirating and moving spheroids for staining or analysis [5] [17]. |

| PrestoBlue / alamarBlue | Cell viability assays optimized for 3D penetration. | Assessing metabolic activity and drug response in spheroids [5] [16]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Fluorescent stain for dead cells, passively diffuses into necrotic cores. | Longitudinal monitoring of cell death within spheroids [14] [15]. |

| Triton X-100 | Detergent for permeabilizing cell membranes before staining. | Enabling antibody and dye penetration for internal spheroid markers [17]. |

| Tissue Clearing Reagents | Enhances optical transparency for deep imaging. | Enabling high-resolution 3D imaging of entire spheroids via confocal microscopy [5] [17]. |

| Image-iT Hypoxia Reagent | Fluorogenic compound detecting oxygen levels below 5%. | Visualizing and quantifying hypoxic regions within large spheroids [16]. |

Experimental Workflow and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for establishing reproducible spheroids for drug screening applications, highlighting the critical parameters identified in the research.

The relationship between the initial cell seeding number and the resulting spheroid characteristics is a fundamental principle for standardizing experiments.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Spheroid Formation Issues

FAQ 1: How can I consistently grow uniform spheroids to get repeatable results?

The Challenge: Well-to-well variability in spheroid size, shape, and growth is a frequently encountered problem that prevents reliable data generation [21].

Solutions:

- Adjust Initial Cell Seeding Density: Control spheroid size by optimizing the number of cells seeded per well [5].

- Select Appropriate Cultureware: Avoid vessels with large surface areas like T-flasks. Instead, use round-bottom microplates (e.g., 96-well U-bottom plates) with ultra-low attachment (ULA) surfaces to promote single spheroid formation per well [5].

- Ensure Homogeneous Cell Suspension: Start with a uniformly mixed cell suspension throughout the plating process to prevent different-sized spheroids from forming due to cellular clumping [22].

- Control Evaporation: Use culture conditions that prevent evaporation-induced medium loss, which is crucial for 384-well plates and other high-throughput formats [21].

FAQ 2: What can I do when my cell lines do not form compact spheroids?

The Challenge: Some cell types resist forming tight, compact spheroids, leading to irregular structures that compromise experimental consistency [5].

Solutions:

- Use Centrifugation: After seeding cells, centrifuge the plate at low speed (e.g., 150 × g for 5 minutes) to help cells quickly settle at the bottom of wells and initiate aggregation [5].

- Allow Extended Formation Time: While some cells form spheroids within hours, others require several days. Be patient and consider replacing half the media volume with fresh media every 2-3 days to maintain culture health during extended formation periods [5].

- Consider ROCK Inhibition: Treatment with ROCK1 inhibitor (Y-27632) can enhance holosphere formation, preserve stemness markers, and reduce premature differentiation in challenging cell types [23].

FAQ 3: How should I handle spheroids for media changes and transfers without damaging them?

The Challenge: The dense, fragile nature of spheroids makes them susceptible to damage during routine handling, which can disrupt experimental timelines [5].

Solutions:

- Gentle Media Changes: Carefully tilt the microplate and slowly aspirate half the supernatant without touching the bottom where spheroids settle. Dispense fresh media along the well wall to avoid breaking spheroids apart [5].

- Use Specialized Pipette Tips: When transferring spheroids between containers, use wide-bore tips or wide-orifice pipette tips to accommodate spheroid diameter and prevent structural damage [5] [24].

- Optimized Centrifugation: For recovering spheroids from suspension, spin tubes briefly (20 seconds at 20 × g) using low centrifugal force to prevent dissociation [24].

FAQ 4: Why do my spheroids develop hypoxic cores and necrotic centers, and how can I manage this?

The Challenge: Spheroids with radii exceeding 200 micrometers develop diffusion limitations, leading to oxygen and nutrient gradients that create hypoxic regions and necrotic cores [25].

Solutions:

- Control Spheroid Size: Regulate initial seeding density to maintain spheroids below critical size thresholds where central necrosis typically develops [25].

- Optimize Feeding Schedules: Larger spheroids have greater nutrient needs and require more frequent media changes to prevent waste accumulation [22].

- Incorporate Transport in Experimental Design: Recognize that hypoxia and nutrient gradients are physiological features of spheroids. For drug testing, account for the limited penetration of therapeutic compounds, which mimics the in vivo barrier to drug delivery [25].

FAQ 5: What modifications are needed for cell viability assays and immunostaining in 3D spheroids?

The Challenge: Reagents and protocols optimized for 2D monolayers often fail to adequately penetrate the thicker, denser structure of 3D spheroids [5].

Solutions for Viability Assays:

- Increase Incubation Times: Allow longer duration for reagents like PrestoBlue HS and alamarBlue HS to penetrate the 3D structure [5].

- Optimize Concentrations: Adjust reagent concentrations specifically for 3D models, as standard 2D concentrations may be insufficient [5].

- Implement Rotation: For tighter, more compact spheroids, consider gentle rotation during incubation to improve reagent penetration [5].

Solutions for Immunostaining:

- Extended Fixation and Permeabilization: Increase incubation times with fixatives and permeabilization buffers (e.g., Triton X-100) to ensure complete penetration through the spheroid [24].

- Incorporate Antigen Retrieval: For formaldehyde-fixed spheroids, include a heat-induced antigen retrieval step (20 minutes at 96-98°C) to unmask epitopes cross-linked during fixation [24].

- Use Tissue Clearing Reagents: Apply commercial tissue clearing reagents specifically designed for 3D cultures to improve antibody penetration and image resolution throughout the spheroid [5].

- Extended Washing and Staining: Implement longer washing steps (e.g., four 1-hour washes) and overnight incubations for primary and secondary antibodies to ensure adequate penetration [24].

Quantitative Data for Spheroid Standardization

Table 1: Spheroid Size Distribution in Heterogeneous Cultures (6-Well ULA Plates)

| Spheroid Type | Cross-Sectional Area (μm²) | Morphological Characteristics | Stem Cell Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holospheres | 408.7 | Large, smooth, compact | BMI-1+ stem cell reservoirs |

| Merospheres | 99.0 | Intermediate size | Moderate regenerative capacity |

| Paraspheres | 14.1 | Small, irregular | Limited stemness potential |

Data adapted from standardized scaffold-free epithelial spheroid systems [23]

Table 2: Protocol Adjustments for 3D vs. 2D Cell Analysis

| Assay Type | Detection Reagent | 2D Protocol | 3D Protocol | Key Modifications for 3D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | CellEvent Green Caspase 3/7 | 1X, 30 min | 1/3X, 2 hours | Lower concentration, longer incubation |

| Mitochondrial Health | MitoTracker Orange | 1X, 30 min | 2X, 1 hour | Higher concentration, extended time |

| Immunostaining | Primary/Secondary Antibodies | Standard overnight | Extended overnight with rotation | Increased penetration time with agitation |

Data compiled from 3D spheroid optimization guidelines [5]

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Uniform Spheroid Formation

Application: Drug screening, toxicity testing, and high-content analysis requiring standardized spheroid sizes [23].

Methodology:

- Platform Selection: Use either Elplasia 96-well Black Round Bottom Microcavity plates or BIOFLOAT 96-well U-Bottom plates

- Cell Preparation: Trypsinize cells, count via trypan blue exclusion, and resuspend at appropriate density:

- Elplasia plates: 1.0 × 10⁶ cells/mL (50 μL aliquot = 5.0 × 10⁴ cells/well)

- BIOFLOAT plates: 1.0 × 10⁵ cells/mL (50 μL aliquot = 5.0 × 10³ cells/well)

- Plate Equilibration: Pre-incubate plates with complete medium for 30 minutes at 37°C

- Seeding and Incubation: Gently dispense cell suspension into wells and incubate undisturbed for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂

- Quality Control: Image multiple non-overlapping fields per well at 4× magnification and quantify spheroid number, diameter, and circularity using automated analysis software [23]

Protocol 2: Spheroid Immunofluorescence for 3D Architecture

Application: Protein localization, cell-cell interactions, and drug penetration studies in intact spheroids [24].

Methodology:

- Fixation: Remove culture medium, wash spheroids 3× with PBS, and fix with either:

- 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 minutes at room temperature

- 100% methanol (chilled at -20°C) for 5 minutes at 4°C

- Wash 3× with PBS after fixation

- Antigen Retrieval (if needed): For formaldehyde-fixed spheroids, incubate in antigen retrieval buffer (Tris/EDTA pH 9.0 or sodium citrate pH 6.0) for 20 minutes at 96-98°C

- Permeabilization: Incubate with permeabilization buffer (PBS with 0.5-2% Triton X-100) for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle shaking

- Blocking: Incubate overnight at room temperature with blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween, 1% BSA, 22.52 mg/mL glycine, and 10% goat serum) on a flat shaker

- Antibody Staining:

- Apply primary antibodies at optimized concentration overnight

- Wash 4× with wash buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween), 1 hour per wash

- Apply secondary antibodies and/or nuclear stain overnight

- Repeat washing protocol (4×1 hour washes)

- Imaging: Mount in appropriate media and image using confocal microscopy with z-stack capability [24]

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Standardized Spheroid Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Spheroid Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function in Spheroid Research |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Attachment Surfaces | Nunclon Sphera plates, Corning ULA plates, BIOFLOAT plates | Inhibit cell attachment to promote 3D aggregation through surface modification or coating [5] [23] |

| Hydrogels/ECM Substrates | Matrigel, synthetic scaffolds, collagen, hyaluronic acid | Provide physiological 3D environment for invasion studies and stemness maintenance [26] [22] |

| Cell Signaling Modulators | ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) | Enhance stemness, improve viability, and promote compact spheroid formation [23] |

| Viability & Staining Reagents | PrestoBlue HS, alamarBlue HS, CellEvent Caspase 3/7, MitoTrackers | Assess metabolic activity, apoptosis, and organelle function in 3D structures [5] |

| Tissue Clearing Reagents | CytoVista 3D Cell Culture Clearing/Staining Kit | Improve antibody and dye penetration for enhanced imaging depth and resolution [5] |

| Specialized Handling Tools | Wide-bore pipette tips, Organoid Harvesting Solution | Enable gentle spheroid manipulation without structural damage during transfer and processing [5] [24] |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Addressing Complex Challenges

FAQ 6: How can I minimize edge effects and evaporation in high-throughput screening?

The Challenge: In 384-well plates, edge effects and evaporation-induced medium loss significantly contribute to well-to-well variability, compromising data reproducibility [21].

Solutions:

- Evaporation Control Systems: Implement culture conditions specifically designed to prevent evaporation-induced medium loss, which has been shown to enable formation of uniform spheroids across entire plates [21].

- Plate Sealing Optimization: Use breathable seals that allow gas exchange while minimizing evaporation during extended incubation periods.

- Environmental Humidification: Ensure adequate humidity levels in incubators to reduce evaporation gradients between edge and center wells.

FAQ 7: How do I standardize spheroid classification and analysis across different experimental setups?

The Challenge: Without standardized classification systems, comparing spheroid populations across experiments and between laboratories remains challenging [23].

Solutions:

- Implement Automated Imaging and Analysis: Use systems like ImageXpress Micro with MetaXpress High-Content Image Acquisition and Analysis Software to quantitatively assess spheroid number, diameter, and circularity [23].

- Establish Size/Shape Categories: Adopt standardized classification based on cross-sectional area and morphology:

- Holospheres: >200 μm, compact, smooth (stem cell reservoirs)

- Merospheres: Intermediate size, moderate regenerative capacity

- Paraspheres: <50 μm, limited stemness potential [23]

- Reference Standard Materials: Include control spheroids with known characteristics in each experimental run to normalize results between batches and platforms.

Standardization Framework for Reliable Data

Step-by-Step Protocols for Robust Spheroid Generation

Three-dimensional (3D) spheroid cultures are pivotal for bridging the gap between traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and complex in vivo environments, offering a more physiologically relevant model for studying tissue biology, disease mechanisms, and drug responses [27]. The reproducibility of spheroid formation is critical for high-throughput screening (HTS) in drug discovery, yet well-to-well variability in size, shape, and growth remains a significant challenge [21]. This guide compares three scaffold-free platforms for spheroid formation—Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates, Hanging Drop, and Agarose Micro-Molds—within the context of standardized protocols for reproducible research. We provide detailed troubleshooting and FAQs to address common experimental issues.

Comparative Platform Analysis: Data and Workflows

Quantitative Comparison of Spheroid Formation Platforms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each platform to inform your selection.

| Platform | Key Principle | Best For | Throughput Potential | Key Advantages | Common Challenges & Variability Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates | Hydrophilic polymer-coated wells prevent cell attachment, forcing aggregation. | High-throughput screening, long-term culture [18] [28]. | High (96-, 384-well formats) [18] | Simple protocol, amenable to automation, suitable for long-term culture and drug testing [18]. | Edge effects and evaporation-induced medium loss; variability in spheroid size and shape; critical dependence on initial cell seeding density [21] [18]. |

| Hanging Drop | Gravitational force aggregates cells in a suspended droplet of medium. | Forming spheroids of uniform size from a defined cell number; forced aggregation [27]. | Medium | Promotes uniform spheroid size; no surface contact prevents aberrant adhesion [27]. | Low-to-medium throughput; cumbersome medium changes; not suitable for long-term culture due to droplet instability. |

| Agarose Micro-Molds | Non-adhesive microwells physically confine cells to guide aggregation. | Maximizing yield and uniformity; applications requiring highly reproducible spheroids [27]. | Medium | Excellent spheroid uniformity; entirely 3D culture environment maximizes cell differentiation potential [27]. | Requires specific mold equipment; medium throughput; potential cell loss during loading. |

Experimental Workflow for Spheroid Formation

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for forming spheroids, applicable across the platforms discussed.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for successful spheroid culture.

| Item | Function / Role | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates | Provides a non-adhesive surface to force cell-cell interactions and spheroid self-assembly. | Corning 96-well Round Bottom ULA Microplates [18] |

| Agarose | Used to create non-adhesive micro-molds or coat plates to prevent cell attachment. | Low-melting point Agarose [28] |

| Serum-Free / Low-Serum Medium | Promotes cellular aggregation and maintains stem cell phenotype; reduces unwanted differentiation. | DMEM/F12 supplemented with EGF and bFGF [27] [28] |

| Dissociation Reagent | Generates a single-cell suspension for accurate counting and uniform spheroid formation. | Accutase [18] |

| Viability Stain | Enables longitudinal monitoring of cell death and necrotic core formation within spheroids. | Propidium Iodide (PI) [18] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How does initial cell seeding density impact spheroid quality and experimental outcomes?

- Answer: Seeding density is a critical parameter. A low initial cell number (e.g., 250-500 cells/well for glioma lines) often promotes better growth and viability than higher densities [18]. There is a linear correlation between the initial cell number and the resulting spheroid size [18]. However, excessively high densities can lead to large spheroids with a substantial necrotic core due to diffusion limits of oxygen and nutrients, which may not be desirable for all assays [18]. You must empirically determine the optimal density for your specific cell line and application.

FAQ 2: We observe high well-to-well variability in spheroid size and growth in our 384-well ULA plates. What could be the cause and how can we improve reproducibility?

- Answer: A primary cause of variability in microtiter plates is evaporation-induced medium loss, which is more pronounced in edge wells and alters growth conditions [21].

- Solution: Implement culture conditions that minimize evaporation. This can include using humidity chambers, plate sealers, or ensuring the incubator has a well-humidified environment. These steps significantly improve the formation of uniform spheroids across the entire plate [21].

FAQ 3: For studying cell differentiation, is there an advantage to using one platform over the others?

- Answer: Yes. Research indicates that the culture microenvironment itself instructs cell differentiation. Studies on cardiac progenitor cells showed that performing spheroid formation and subsequent differentiation exclusively in a 3D microenvironment using agarose micro-molds maximized cardiomyocyte yield compared to methods requiring a 2D-to-3D switch (like ULA plates and hanging drop) [27]. A 3D culture system is necessary for robust differentiation [27].

FAQ 4: Our spheroids are forming, but we notice a significant central core of dead cells. Is this a problem?

- Answer: The development of a necrotic core is a natural consequence of spheroid growth and mimics the nutrient and oxygen gradients found in real tumors [18]. The size of this core is cell-line dependent and changes over time [18]. For drug screening, this structure can be desirable as it models a therapeutic barrier. However, if a large necrotic core is undesirable for your specific experiment, you should reduce the spheroid size by lowering the seeding density or the culture period.

FAQ 5: What is the recommended method for feeding spheroids during long-term culture without disrupting them?

- Answer: A standard protocol is to perform partial medium changes every 3 to 4 days [18]. Carefully remove approximately 50% of the spent medium from the well (e.g., using a multi-channel pipette with a slow, steady hand) and gently replace it with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed culture medium. This approach maintains nutrient and waste levels while minimizing physical disturbance to the spheroids.

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for 3D Cell Culture. This resource addresses the critical challenge of cell seeding optimization to enhance the reproducibility of spheroid research. Inconsistent initial seeding is a primary source of variability, affecting spheroid size, morphology, structural integrity, and experimental outcomes. The following guides and FAQs, grounded in recent large-scale studies, provide actionable strategies to standardize your protocols and achieve reliable results.

★ Key Factor Tables for Experimental Design

Table 1: Influence of Culture Conditions on Spheroid Attributes

| Factor | Optimal Range / Condition | Impact on Spheroid Attributes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Seeding Density | 2,000 - 6,000 cells/spheroid (cell line-dependent) | Size & Stability: Higher density (6,000-7,000) increases size but can cause structural instability and rupture [10]. | - MCF-7 spheroids shrink over time; HCT 116 spheroids grow [10].- Densities of 6000 cells showed lowest compactness, solidity, and sphericity [10]. |

| Serum Concentration (FBS) | 10% - 20% | Structural Integrity: Concentrations below 5% lead to spheroid shrinkage, reduced density, and increased cell death [10] [29]. | - 10-20% FBS promotes dense spheroids with distinct necrotic and proliferative zones [10].- ATP content drops over 60% in serum concentrations below 5% [10]. |

| Oxygen Level | Physioxia (e.g., 3% O₂) | Viability & Morphology: Hypoxic conditions (3% O₂) reduce spheroid dimensions, viability, and ATP content [10]. | - 3% O₂ is associated with a heightened PI signal in the necrotic core and can influence co-culture outcomes [10] [29]. |

| Media Composition | Cell line-specific | Growth & Death Profiles: Varying glucose and calcium levels significantly affect spheroid size, shape, and viability [10]. | - HEK 293T spheroids in RPMI 1640 showed significantly elevated cell death signals [10] [29]. |

Table 2: Recommended Seeding Densities for Different Platforms

| Platform / Cell Type | Typical Seeding Density Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Adherent Culture [30] | Varies by vessel surface area | - Passage cells at log phase with >90% viability.- Optimize density for 50-90% confluency. |

| XFp Miniplates (Adherent Cells) [31] | 5 x 10³ - 4 x 10⁴ cells/well | - Density should result in 50-90% confluency for dynamic metabolic rates. |

| XF HS Miniplates (Adherent Cells) [31] | 1.0 x 10³ - 1.0 x 10⁴ cells/well | - Seeding area is ~30% of a standard XFp plate; requires density optimization. |

| 96-Well U-Bottom Plate (for Spheroids) [32] | 10,000 cells/well in 100 µL | - Mixed with 1% methylcellulose to promote aggregation. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How does initial seeding density affect my 3D spheroid model?

The initial cell number is a primary determinant of final spheroid size and integrity. However, the relationship is not always linear and is cell line-dependent [10].

- Low Density (<2,000 cells/spheroid): May yield small, less dense spheroids that lack robust cell-cell interactions.

- High Density (>6,000 cells/spheroid): Can lead to large but unstable spheroids. Studies show that spheroids formed from 6,000-7,000 cells can rupture, releasing necrotic and proliferative areas [10]. Interestingly, some cell lines like MCF-7 can exhibit self-repair capabilities after structural failure [10].

FAQ: Why are my spheroids inconsistent across a multi-well plate?

Well-to-well variability is a common challenge in high-throughput screening, often caused by evaporation-induced medium loss at the plate edges, leading to the "edge effect" [21].

- Solution: Use culture conditions that prevent evaporation, such as humidity chambers or plate seals. Ensuring uniform medium volume across all wells is critical for forming identical spheroids [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Spheroid Disintegration or Rupture

- Problem: Spheroids break apart, lose structural integrity, or release cells.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Excessive Seeding Density: This is a common cause. Solution: Titrate the initial cell number downward. Establish a growth curve for your cell line to find the density that maintains stability over your desired culture period [10].

- Insufficient Cell-Cell Adhesion: Solution: Optimize media composition, particularly serum concentration. For MCF-7 cells, maintaining at least 10% FBS promotes the formation of compact, dense spheroids [10] [29]. For serum-free cultures, consider incorporating natural polymers like methylcellulose to support aggregation [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: High or Variable Cell Death in Spheroids

- Problem: Excessive central necrosis or uneven cell death signals.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Incorrect Media Formulation: Solution: Be aware that standard media like RPMI 1640 can intrinsically promote higher death signals in some cell types (e.g., HEK 293T) [10] [29]. Test different media to find the optimal one for your specific cell line.

- Sub-optimal Serum Concentration: Solution: Avoid very low serum (0.5%-1%). Data shows cell death is highest at these concentrations. Use 10-20% FBS for improved viability, unless experimentally required otherwise [10].

- Severe Hypoxic Core: Solution: If excessive necrosis is undesirable, consider reducing the initial seeding density to create a smaller spheroid with less pronounced nutrient/waste gradients.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Forming Spheroids in U-Bottom Plates with Methylcellulose

This is a widely used, scaffold-free method for generating uniform spheroids [32].

Workflow: Spheroid Formation

Materials:

- U-bottom 96-well plate (not tissue culture treated) [32]

- Methylcellulose (1% in PBS): Acts as a viscosity enhancer to prevent cell adhesion to the plate bottom and force aggregation [32].

- Complete Growth Medium: e.g., RPMI 1640 or DMEM, supplemented with FBS and antibiotics [32].

- Wide-orifice pipette tips: Essential for transferring formed spheroids without causing shear stress [32].

Procedure:

- Prepare a 1% solution of methylcellulose in PBS and sterilize [32].

- Harvest and count your cells. Calculate the volume needed for 10,000 cells per spheroid [32].

- In a tube, mix the cell suspension with an equal volume of 1% methylcellulose. The final volume per spheroid will be 100 µL [32].

- Seed 100 µL of the cell-methylcellulose mixture into each well of the U-bottom plate.

- Centrifuge the plate at a low speed (e.g., 300-500 x g for 1-2 minutes) to gently pellet the cells into the well bottom and initiate aggregation.

- Incubate the plate for 3 days at 37°C and 5% CO₂. Spheroids should form within this period [32].

Protocol 2: Passaging and Seeding Adherent Cells for 2D Culture

Proper subculture is fundamental to ensuring healthy, reproducible starting material for spheroid formation [30].

Materials:

- Pre-warmed Dissociation Reagent: e.g., trypsin or TrypLE [30].

- Balanced Salt Solution: without calcium and magnesium (e.g., PBS) [30].

- Complete Growth Medium: containing serum to inactivate the dissociation reagent [30].

- Hemocytometer or Automated Cell Counter [30].

Procedure:

- Monitor Cell Confluency: Only passage adherent cells when they are in the log phase of growth and have a viability >90% [30].

- Remove and Discard spent culture media from the vessel [30].

- Wash Cells with the balanced salt solution (~2 mL per 10 cm²) to remove traces of serum and ions. Gently rock the vessel and discard the wash [30].

- Add Dissociation Reagent (~0.5 mL per 10 cm²) to cover the cell layer. Rock the vessel for complete coverage [30].

- Incubate at room temperature for ~2 minutes (time varies by cell line). Observe under a microscope until ≥90% of cells detach. Gently tap the vessel if needed [30].

- Neutralize the reaction by adding 2 volumes of complete growth medium. Pipette thoroughly to disperse the cells [30].

- Transfer the cell suspension to a conical tube and centrifuge at 200 x g for 5-10 minutes. Resuspend the pellet in a known volume of fresh medium [30].

- Count Cells and calculate total cell number and viability using Trypan Blue exclusion or an automated counter [30].

- Dilute the cell suspension to the desired seeding density for your experiment or for continued 2D maintenance [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Cell Seeding & Spheroid Culture |

|---|---|

| Methylcellulose | A polymer used in scaffold-free spheroid formation to increase medium viscosity, preventing cell adhesion to the plate and promoting 3D aggregation [32]. |

| U-Bottom Microplates | Non-adherent plates with a round well bottom that guide cells to aggregate into a single spheroid per well, ideal for uniform high-throughput production [32]. |

| Wide-Orifice Pipette Tips | Tips with a larger opening to minimize shear forces when aspirating or transferring delicate 3D structures like spheroids, preserving their integrity [32]. |

| Trypsin/TrypLE | Enzymatic dissociation reagents used to detach adherent cells from culture vessels for passaging and counting before setting up seeding experiments [30]. |

| CellTiter-Glo 3D | A luminescent assay optimized for 3D models that measures ATP content, providing a quantitative readout of cell viability within dense spheroids [29]. |

| Automated Cell Counter | Provides a fast and consistent count of cell concentration and viability, reducing human error inherent to manual hemocytometer counting [30] [31]. |

Advanced Analysis: From Images to Quantitative Data

Modern spheroid research relies on high-throughput image analysis to extract robust, quantitative data. Studies analyzing tens of thousands of spheroids use software like AnaSP and ReViSP to compute metrics such as sphericity, compactness, solidity, and Feret diameter [10] [29]. These parameters allow researchers to move beyond subjective descriptions and statistically compare spheroid morphology across different experimental conditions.

Parameter Relationships in Spheroid Analysis

Furthermore, AI-based segmentation pipelines like 3DCellScope and DeepStar3D are now enabling high-speed 3D analysis of entire organoids, quantifying cellular morphology and topology at the single-cell level within these complex structures [33]. Integrating these tools is key for the future of standardized, reproducible 3D research.

Protocol for 384-Well Hanging Drop Plates for Patient-Derived Cells

The 384-well hanging drop plate is a high-throughput, scaffold-free three-dimensional (3D) cell culture platform designed to generate uniform tumor spheroids, particularly from patient-derived cells such as cancer stem cells (CSCs) [34]. This system excels in creating a physiologically representative microenvironment that recapitulates critical features of the in vivo tumor niche, including physiological cell-cell contacts, diffusion gradients, cell densities, and naturally produced extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins [34]. Its primary application in personalized medicine is for high-throughput drug screening to identify patient-specific treatment strategies and develop new therapeutics, as it allows for rapid screening using small numbers of precious patient-derived cells and is highly amenable to various downstream analyses [34].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for generating and analyzing spheroids using the 384-well hanging drop platform.

Detailed Protocols & Methodologies

Plate Preparation and Sterilization

Proper plate preparation is critical for preventing spheroid adhesion and ensuring experimental success.

- Sonication and Cleaning: Place the hanging drop plate in a sonicator filled with sterile deionized (DI) water and sonicate for 20 minutes. Remove and wash with running DI water [34].

- Pluronic Coating: Submerge the plate in a bath of 0.1% Pluronic acid for 24 hours to prevent protein adsorption and spheroid adherence [34].

- Rinsing and Drying: Thoroughly rinse both sides of the plate with running DI water. Inside a biosafety cabinet, vigorously tap or shake the plate to remove water from the wells [34].

- Sterilization: Sterilize the plate by exposing each side to UV light for 30–60 minutes. Alternatively, use an ethylene oxide gas chamber [34].

Humidity Chamber Assembly

Evaporation from the hanging drops must be minimized to maintain culture stability.

- Procedure: Fill each well of a 6-well plate with 4–5 mL of sterile autoclaved DI water. Sandwich the prepared hanging drop plate between the lid and bottom of the 6-well plate. Add 800–1,000 µL of sterile DI water around the rim of the hanging drop plate to create a humid, stable environment [34]. A 3D-printed humidity chamber can also be used for this purpose [35].

Spheroid Generation from Patient-Derived Cells

- Cell Suspension Preparation: For patient-derived cells collected from primary or metastatic solid tumors or ascites, prepare a single-cell suspension in an appropriate serum-free medium (SFM) [34]. Resuspend the cell pellet in culture medium supplemented with 0.5-1.0% methylcellulose to facilitate stable spheroid morphology. Methylcellulose increases the viscosity of the medium, preventing sedimentation of cells to the bottom of the drop and promoting uniform spheroid formation [36].

- Plate Seeding: Pipette a 28 µL aliquot of the cell suspension into each well of the hanging drop plate. A common seeding density is 20,000 cells in 28 µL of medium [36].

- Incubation and Spheroid Formation: Carefully place the assembled humidity chamber containing the seeded plate in a 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator. Spheroids typically form within 3 to 7 days [36].

Spheroid Transfer for Downstream Analysis

The TRIM (Transfer and Imaging) plate is a complementary tool designed for facile handling of hanging drop spheroids [37].

- Contact-Based Transfer:

- Align the TRIM plate with the hanging drop plate using the physical plate guides.

- Lower the hanging drop plate to make contact with the TRIM plate.

- Allow spheroids to settle into the transfer wells for 1–2 minutes.

- Evenly lift and separate the hanging drop plate. This process results in nearly 100% spheroid capture efficiency [37].

- Advantages: The low-aspect ratio wells of the TRIM plate facilitate bulk spheroid collection for flow cytometry and enable high-resolution, low-working-distance immersion imaging [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 1: Key reagents and materials for the 384-well hanging drop protocol.

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| 384-Well Hanging Drop Plate | Platform for spheroid formation in a pendant droplet. | Available from commercial suppliers (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich #HDP1385) [36]. |

| Pluronic F-127 (0.1%) | Non-ionic surfactant to coat plates and prevent spheroid adhesion. | Critical for preventing protein adsorption [34]. |

| Methylcellulose | Agent to increase medium viscosity, stabilizing the hanging drop and promoting uniform spheroid formation. | e.g., Methocel A4M [36]. |

| TRIM Plate | Complementary plate for high-fidelity transfer, bulk collection, and immersion imaging of spheroids. | Fabricated using SLA 3D printing [37]. |

| Patient-Derived Cell Suspension | Primary cells from solid tumors or ascites for physiologically relevant spheroid generation. | Prepared in serum-free medium (SFM) [34]. |

| Humidity Chamber | System to maintain a humid environment and minimize droplet evaporation. | Can be a 6-well plate with water or a custom 3D-printed chamber [34] [35]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Spheroid Morphology and Uniformity

Issue: High variability in spheroid size and shape. Poor spheroid uniformity is a significant source of data variability in drug response assays [38]. Both spheroid volume and shape (sphericity index) can affect treatment response [38].

- Solution: Use morphological pre-selection before initiating experiments. Software tools like AnaSP (open-source) can automatically analyze brightfield images and quantify parameters like volume and sphericity. Select only spheroids with homogeneous volume and a high sphericity index (SI ≥ 0.90) for treatment assays to drastically improve data reproducibility [38].

Issue: Spheroids are loose or do not form properly.

- Solution: Ensure the cell suspension is a true single-cell suspension. Optimize the concentration of methylcellulose (e.g., 0.5-1.0%) in the culture medium to enhance cell aggregation and spheroid compaction [36].

Technical and Handling Problems

Issue: Excessive evaporation from hanging drops.

- Solution: Verify the integrity of the humidity chamber. Ensure an adequate volume of sterile water is present in the reservoir wells and around the plate rim. Consider using a dedicated 3D-printed humidity chamber for better sealing [35].

Issue: Spheroids stick to the plate or are difficult to transfer.

- Solution: Confirm the Pluronic coating step was performed correctly and that the plate was rinsed thoroughly after coating. For transfer, use a dedicated TRIM plate or ensure pipetting techniques are gentle and consistent to avoid spheroid disruption [34] [37].

Issue: Contamination in the cultures.

- Solution: Maintain strict aseptic technique during all steps, particularly during the plate seeding process. Ensure the plate sterilization step (UV or ethylene oxide) is performed effectively [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of the 384-well hanging drop platform over other 3D culture methods like hydrogels or ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates? The 384-well hanging drop platform offers several key advantages:

- High Throughput: The 384-well format allows for many parallel experiments with minimal cell numbers, ideal for drug screening [34].

- High Uniformity: It generates spheroids with a narrow size distribution (variation coefficients of 10-15%), superior to many non-adherent surface methods (40-60%) [36].

- Physiological Relevance: Spheroids exhibit higher compaction, remodeling, and chemoresistance compared to those from ULA plates, better mimicking in vivo conditions [34].

- Ease of Analysis: It is highly amenable to downstream analysis like imaging, flow cytometry, and viability assays [34].

Q2: How can I modify the size of the spheroids? Spheroid size can be controlled by adjusting two key parameters:

- Cell Seeding Density: Higher cell numbers will yield larger spheroids [36].

- Volume of the Droplet: The platform allows for control of spheroid size by adjusting the volume of the droplet or the concentration of cells in the suspension [36].

Q3: My drug screening results are variable. What could be the cause? The most common cause is morphological heterogeneity in the spheroid population used for the assay [38]. Pre-select spheroids based on volume and shape (sphericity index) to ensure a homogeneous population before treatment. Additionally, confirm that your viability assay is validated for 3D cultures, as conventional 2D assays may not be suitable [38].

Q4: What downstream applications are compatible with spheroids from this platform? The platform is compatible with a wide range of analyses:

- Imaging: Brightfield, confocal, and multiphoton microscopy (facilitated by the TRIM plate) [34] [37].

- Viability and Cytotoxicity Assays: e.g., ATP-based assays, WST-1 proliferation assay [35] [38].

- Flow Cytometry: For cell phenotype analysis after spheroid dissociation [34] [37].

- Molecular Biology: PCR, gene expression analysis [34].

- Other: Immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry, ELISA on conditioned medium [34].

Decision-Making Guide for Spheroid Quality Issues

The following flowchart provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving common spheroid quality problems.

Protocol for 96-Well ULA Plates for Rapid, Large-Scale Production

The adoption of three-dimensional (3D) cell cultures, particularly spheroids, represents a significant advancement in preclinical research, bridging the gap between traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayers and in vivo models. Spheroids better mimic the complex architecture and microenvironment of solid tumors by incorporating dynamic cell-cell interactions and developing an extracellular matrix (ECM), which influences critical processes like drug penetration and the development of resistance gradients [4]. Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) plates provide a scaffold-free method for generating uniform, self-assembled spheroids, making them indispensable for high-throughput screening and drug efficacy evaluation [39]. Standardized protocols are essential to overcome challenges in reproducibility and scalability, ensuring that data generated from these advanced models is both reliable and translatable.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

General Protocol and Spheroid Formation

Q: What is the key advantage of using U-bottom ULA plates over flat-bottom plates for spheroid formation?

- A: U-bottom plates are engineered to guide the self-assembly of cells into a single, uniform spheroid that is centered within each well. In contrast, flat-bottom plates often result in multiple, non-uniform cell aggregates, leading to inconsistent data [39].

Q: How do I control the size of the spheroids?

- A: Spheroid size is primarily dependent on the initial plating density and the cell type used. The duration of the culture and the desired size at the time of analysis are also key factors. Optimization of seeding density is required for each new cell line [39].

Q: How long does it take for spheroids to form?

- A: Many common cell lines will form a spheroid within 24 hours. However, some cell types may form looser aggregates and require optimization, such as media supplementation with methylcellulose or co-culture with fibroblasts [39].

Q: What is the recommended workflow to ensure consistent spheroid formation?

- A: A standardized workflow is critical for reproducibility. The key steps are summarized in the following diagram:

Spheroid Production Workflow

- A: A standardized workflow is critical for reproducibility. The key steps are summarized in the following diagram:

Common Issues and Solutions

Even with a standardized protocol, researchers may encounter specific challenges. The table below outlines common problems, their likely causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple aggregates form per well | - Damaged ULA coating from pipette tip- Pre-existing cell clumps in suspension | - Avoid touching well bottom/sides during pipetting [39]- Filter cell suspension through a 40 µm cell strainer [39] |

| Spheroid does not form; cells remain loose | - Cell type requires matrix support- Incorrect media composition | - Optimize media (e.g., add methylcellulose) [39]- Consider a scaffold-based method [40] |

| High well-to-well variability in size | - Inconsistent cell seeding density- Evaporation in edge wells | - Ensure homogeneous cell suspension by gentle pipetting before seeding [41]- Maintain >95% incubator humidity; use low-evaporation lids [41] |

| Spheroid is aspirated during medium exchange | - Pipetting too close to the spheroid- Excessive pipetting speed | - Use a pipette tip placed at the ledge of the well, away from the spheroid [41] [39]- Aspirate and dispense media slowly (<30-50 µL/sec) [41] |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Parameters

Successful large-scale production relies on precise control of quantitative parameters. The following table consolidates key data for planning experiments with 96-well ULA plates.

| Parameter | Specification / Recommended Value | Notes / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Max Well Volume | 250-300 µL [39] | A working volume of 70 µL is often used for optimal spheroid formation [41]. |

| Recommended Seeding Density | 250 - 2,500+ cells/well [41] | Low end (250-500) for long-term growth; high end for non-proliferating cells or large spheroids. Must be optimized per cell line. |

| Centrifugation after Seeding | 250 RCF for 2 minutes [41] | Promotes cell aggregation and removes air bubbles. |

| Residual Volume after Aspiration | 5-7 µL [41] | Achieved by using the plate's built-in ledge during medium exchange to prevent spheroid loss. |

| Plate Storage Conditions | Room temperature, low humidity [39] | Protect from direct sunlight. Do not use if packaging is damaged. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A standardized protocol requires the use of specific, high-quality materials. The table below lists essential items for spheroid production in 96-well ULA plates and their critical functions.

| Item | Function in Spheroid Production |

|---|---|

| 96-Well ULA U-bottom Plate | The core platform that prevents cell attachment, forcing cells to aggregate into a single, centered spheroid in each well [39]. |

| Phenol Red-Free Medium | Prevents coloring of the medium and potential imaging artifacts, especially when used with ECM components for embedded cultures [40]. |

| Single-Cell Suspension | The starting point for uniform spheroid formation. Achieved via trypsin-EDTA dissociation and optional filtration [40] [39]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | A standard supplement (e.g., 10%) in complete media that supports cell growth and viability [40]. |

| Methylcellulose | A media additive used to increase viscosity for cell types that form loose aggregates, promoting tighter spheroid formation [39]. |

| Automation-Compatible Seals/Lids | Low-evaporation lids are critical for long-term cultures to minimize media concentration in edge wells and ensure experimental consistency [41]. |

Advanced Applications and Analysis

The 96-well ULA plate format is compatible with a wide range of downstream applications, making it a powerful tool for drug development.

- Drug Efficacy and Screening: Spheroids are ideal for evaluating anti-cancer drugs, especially for assessing penetration and effects on the hypoxic inner core [4] [39]. The 96-well format is suited for high-throughput screening of compound libraries.

- Live/Dead Staining and Fluorescence Imaging: The plates are optically clear, allowing for in-well fluorescent assays to monitor cell viability, cell division, and other physiological processes within the spheroid over time [39].

- High-Content Analysis (HCA): Spheroids generated in this format can be analyzed using HCA to extract quantitative features at both the whole-spheroid level and the individual cell level, providing deep phenotypic data [40].

The relationships between the spheroid model, the experimental perturbations, and the resulting data outputs are complex. The following diagram illustrates this integrated experimental and analysis pipeline:

Spheroid Research Feedback Loop

The implementation of a standardized protocol for 96-well ULA plates, as outlined in this guide, is a critical step toward achieving reproducible, large-scale production of spheroids. By adhering to detailed methodologies for plate handling, cell seeding, and medium exchange, and by understanding the troubleshooting principles, researchers can minimize variability and generate robust, high-quality data. The ability to create uniform 3D models in a high-throughput format directly addresses the growing demand for more physiologically relevant systems in drug discovery and cancer research, ultimately helping to bridge the gap between in vitro studies and clinical outcomes.

The AggreWell System Guide for Production of Size-Controlled Spheroids

The pursuit of highly reproducible, physiologically relevant three-dimensional (3D) cell models is a central goal in modern life sciences. The AggreWell microwell system addresses this need by providing a standardized platform for the robust production of size-controlled spheroids and embryoid bodies (EBs). This technology utilizes forced cellular aggregation to generate large numbers of uniform 3D microtissues, directly supporting the broader thesis that standardized protocols are paramount for achieving reproducible and reliable results in spheroid-based research [42]. By controlling the initial seeding parameters, researchers can directly determine the final spheroid size, a critical factor that influences diffusion gradients, cellular differentiation, and overall morphology, thereby reducing experimental variability and enhancing data quality [43] [44] [42].

The AggreWell system consists of plates containing a high-density array of pyramid-shaped microwells. The operational principle involves centrifuging a single-cell suspension into these microwells, where cells cluster at the bottom of each well to form a single aggregate [42]. The size of the resulting spheroid or EB is controlled by adjusting the initial cell seeding number, while the microwell geometry ensures consistent shape and size across thousands of aggregates simultaneously [43] [45]. The system is compatible with a wide range of cell types, including pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) for EB formation, cancer cell lines for tumor spheroids, and other primary cells [43] [42] [45].

The table below summarizes the key specifications for the different AggreWell plate formats to guide appropriate selection based on experimental needs.

Table 1: AggreWell Plate Specifications and Selection Guide

| Plate Format | Microwell Diameter (µm) | Aggregate Size Range (Cells/Spheroid) | Approx. Aggregates per Well | Total Aggregates per Plate | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AggreWell400 | 400 | 50 - 3,000 [43] | 1,200 (24-well) [43] | ~28,000 [43] | Embryoid bodies for ES/iPS cell differentiation; smaller cancer spheroids; high-throughput imaging [45] |

| AggreWell800 | 800 | 3,000 - 20,000 [43] | 300 (24-well) [43] | ~7,200 [43] | Larger embryoid bodies; large cancer spheroids; 3D tissue engineering [45] |

| AggreWellHT | 900 | 50 - 20,000 [43] | 32 (96-well) [43] | ~3,072 [43] | Drug screening; applications requiring individual well handling [45] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core process of spheroid formation using the AggreWell system.

Figure 1: Standardized Workflow for AggreWell Spheroid Formation. This diagram outlines the key steps from cell preparation to spheroid harvest, highlighting critical actions for success.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Microwell Plate Preparation

Proper plate preparation is critical for preventing cell adhesion and ensuring the efficient formation and retrieval of spheroids.

- Aseptic Technique: Perform all steps in a sterile laminar-flow biosafety cabinet. The plates are sterile as supplied [42].