Strategic Bioreactor Scale-Up Optimization: Bridging Lab-Scale Success to Industrial Manufacturing

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the critical challenge of bioreactor scale-up.

Strategic Bioreactor Scale-Up Optimization: Bridging Lab-Scale Success to Industrial Manufacturing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the critical challenge of bioreactor scale-up. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation strategies, it explores the core physical and biological hurdles like gradient formation and mixing inefficiencies. The content delivers actionable methodologies including scale-down models, CFD simulations, and statistical DoE, alongside proven troubleshooting techniques for issues such as oxygen transfer and contamination. A thorough analysis of validation protocols and comparative technology assessments equips scientists with the knowledge to de-risk scale-up, ensure regulatory compliance, and achieve robust, commercially viable bioprocesses for biologics and advanced therapies.

Understanding Scale-Up Challenges: The Core Principles and Hurdles in Bioprocess Translation

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our cell viability drops significantly when we move from a 5 L to a 500 L bioreactor. What could be causing this?

A: A sudden drop in cell viability is often linked to increased shear stress or inadequate mixing at the larger scale.

- Root Cause: In larger tanks, achieving homogeneity requires more aggressive agitation. This can generate higher shear forces from impellers and air bubbles, damaging delicate cells [1] [2]. Furthermore, poor mixing can create zones with low nutrient or oxygen concentration [3].

- Solution:

- Optimize Agitation: Consider using low-shear impellers (e.g., pitched-blade) instead of high-shear ones (e.g., Rushton). Start with lower agitation speeds and gradually increase while monitoring viability [4] [5].

- Evaluate Sparger Design: Smaller bubbles from finer spargers improve oxygen transfer but can increase cell damage at the liquid surface. Optimize bubble size by selecting an appropriate sparger pore size [1] [6].

- Conduct Scale-Down Studies: Use lab-scale bioreactors to mimic the predicted shear and mixing conditions of the large-scale tank. This allows you to identify the tolerance of your cell line and refine process parameters safely [3] [5].

Q2: How can we maintain optimal dissolved oxygen levels in a large-scale bioreactor when it was easy at the lab scale?

A: Oxygen transfer is a common bottleneck because the surface-to-volume ratio decreases with scale, making oxygen dissolution harder [1] [2].

- Root Cause: The volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa) is often the limiting factor. In large tanks, the oxygen transfer rate may not keep pace with higher cell densities [7] [8].

- Solution:

- Focus on kLa: Base your scale-up strategy on maintaining a constant kLa rather than a constant power input per volume (P/V) alone [8] [9].

- Optimize Aeration System: Adjust the gas sparging rate and use spargers (e.g., drilled-hole sparger - DHS) designed to maximize the gas-liquid interfacial area without causing foaming or cell damage [1] [6].

- Increase Reactor Pressure: Moderately increasing the headspace pressure can enhance oxygen solubility and improve kLa [7].

Q3: Why is our product yield inconsistent between batches in our pilot-scale bioreactor?

A: Batch-to-batch inconsistency often stems from environmental gradients and raw material variability that become pronounced at larger scales [2] [3] [5].

- Root Cause: Large bioreactors can develop gradients in pH, temperature, and nutrient concentration. Mixing times are longer, so feed additions may not distribute instantly. Furthermore, switching from lab-grade to industrial-grade raw materials can introduce inhibitors or variability [3].

- Solution:

- Improve Process Control: Implement advanced control loops for feeding, pH, and temperature that respond to real-time sensor data. Use design of experiments (DoE) to find robust operating ranges [1] [6].

- Validate Raw Materials: Qualify all industrial-grade raw materials in lab-scale or pilot-scale studies before using them in production to ensure they support consistent growth and productivity [3].

- Ensure Geometric Similarity: When scaling up, strive to maintain geometric similarity between bioreactors (e.g., aspect ratio, impeller type and placement) to create a more uniform environment [8] [5].

Scale-Down Modeling: An Essential Experimental Protocol

When a production-scale batch fails, investigating the root cause directly in the large tank is costly and impractical. Scale-down modeling is a critical methodology that recreates production-scale conditions in a small, lab-scale bioreactor, enabling efficient troubleshooting and process optimization [3] [5].

Experimental Protocol: Investigating a Dissolved Oxygen Gradient Issue

Objective: To replicate and solve a periodic dissolved oxygen (DO) dip observed in a 10,000 L production bioreactor using a 10 L lab-scale system.

Background: Large bioreactors can develop spatial gradients of DO. Cells circulating through the tank experience fluctuating oxygen levels, which can impact metabolism and yield. This dynamic environment is not captured in well-mixed small-scale reactors [3].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Bioreactor System: A 10 L lab-scale bioreactor (e.g., INFORS HT Techfors) with advanced programmatic control over agitation speed and gas flows [5].

- Sensors: Standard in-situ probes for DO, pH, and temperature.

- Analytical Tools: Offline analyzer for metabolites (e.g., glucose, lactate), cell counter, and product titer assay.

Methodology:

- Process Analysis: Analyze data from the 10,000 L run to characterize the frequency and amplitude of the DO dips. Use computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models of the large tank to understand the mixing time and power input per volume (P/V) in different zones [7] [3].

- Model Programming: In the 10 L bioreactor's control software, program an agitation profile where the stirrer speed oscillates between high and low setpoints. This creates timed intervals of good and poor mixing, simulating the cells moving through different environments in the large tank [3] [5].

- Example: Alternate between 300 rpm for 15 seconds (well-mixed zone) and 100 rpm for 30 seconds (poorly-mixed zone).

- Experimental Run: Inoculate the bioreactor with the same cell line and run the process using the base production recipe, but with the dynamic agitation profile applied.

- Monitoring: Intensively sample and monitor cell growth, viability, key metabolite levels, and final product titer. Compare this data with runs under constant optimal mixing and with data from the failed production batch.

- Solution Testing: Once the problem is replicated, test solutions in the scale-down model. This could involve:

- Adjusting the feed profile to be less concentrated.

- Implementing a cascade control that links the agitation rate and oxygen sparging to the DO setpoint.

- Slightly increasing the DO setpoint to ensure the "low" point in the oscillation does not become critically anoxic.

Expected Outcome: This protocol identifies the precise impact of dynamic DO gradients on your process and validates a robust solution at minimal cost before committing to another large-scale production run [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for Scale-Up Studies

The following table details key materials used in advanced bioreactor scale-up experiments, particularly for cell culture processes.

| Item | Function in Scale-Up Research |

|---|---|

| Porous Microcarriers | Provides a high surface-to-volume ratio (10-100x traditional carriers) for growing adherent cell lines in suspension bioreactors, enabling massive scale-up of cell densities while offering protection from mechanical stress [4]. |

| Drilled-Hole Sparger (DHS) | A gas distributor critical for aeration. Its pore size (typically 0.3-1.0 mm) directly impacts bubble size, oxygen mass transfer efficiency (kLa), and CO2 stripping, making its optimization essential during technology transfer between different bioreactors [6]. |

| Industrial-Grade Raw Materials | Lower-cost, large-volume versions of growth media components. Must be validated in scale-down models to check for impurities or variability that can negatively impact fermentation consistency and yield at production scale [3]. |

| Suspension-Adapted Cell Lines | Cell lines (e.g., HEK293) genetically adapted to proliferate freely in suspension, eliminating the need for microcarriers and simplifying scale-up in large stirred-tank bioreactors [4]. |

| Chemical Antifoaming Agents | Controls excessive foam formation caused by vigorous aeration and agitation in large tanks. Prevents foam-over, which risks contamination and loss of sterility [8]. |

Quantitative Data for Scale-Up Planning

Successful scale-up requires careful consideration of how key parameters change with volume. The table below summarizes critical scale-dependent parameters and their impacts.

| Parameter | Typical Scale-Dependent Deviation | Potential Impact on Process |

|---|---|---|

| Mixing Time | Increases significantly with scale [1] [3] | Creates gradients in nutrients, pH, and dissolved oxygen, leading to non-uniform cell populations and inconsistent product quality [1] [8]. |

| Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa) | Becomes a limiting factor; gradients can form [7] [3] | Can lead to oxygen limitation in certain zones of the bioreactor, affecting cell metabolism, viability, and productivity [1] [2]. |

| Power Input per Volume (P/V) | May be held constant, but distribution can be uneven [9] | Impacts mixing, mass transfer, and shear stress. An uneven distribution means some cells experience high shear while others experience stagnation [1] [3]. |

| Broth Hydrostatic Pressure | Increases with liquid height [7] [3] | Elevated pressure at the bottom increases dissolved gas partial pressures (pCO2, pO2), which can inhibit or alter cellular metabolism [7] [3]. |

| Shear Stress | Increases due to higher impeller tip speed and air bubble rupture [1] [2] | Can cause physical damage to cells (lysis), reduced viability, and altered protein expression [4] [2]. |

Advanced Strategy: Integrating Aeration Pore Size and Scale-Up

Traditional scale-up strategies based on constant P/V or kLa often overlook the critical role of sparger design. Recent research highlights the need for a dynamic initial aeration (vvm) strategy that accounts for aeration pore size to optimize monoclonal antibody production in single-use bioreactors [6].

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Aeration with a DoE Approach

Objective: To establish a quantitative relationship between aeration pore size, initial vvm, and P/V for optimal cell growth and productivity.

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach, such as an orthogonal array, to efficiently test multiple factors simultaneously. The key factors are:

- P/V (e.g., 8.8, 18.8, 23.8, 28.8 W/m³)

- Vvm (e.g., 0.003, 0.0075, 0.012 m³/min)

- Aeration Pore Size (e.g., 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0 mm) [6]

- Setup: Use parallel miniature bioreactor systems (e.g., 500 mL working volume) to ensure consistency across all experimental runs.

- Execution: Run the cell culture process (e.g., with a CHO or HEK293 cell line producing a monoclonal antibody) under each condition defined by the DoE matrix.

- Analysis: Monitor critical process parameters (CPPs) like cell density, viability, and metabolite levels. The critical quality attribute (CQA) is the final product titer. Use statistical software to build a model linking the factors to the output.

- Validation: Validate the model's predictions first in a 15 L glass bioreactor, then in a 500 L single-use production bioreactor.

Key Finding: Research demonstrates a clear quantitative relationship. For example, in a P/V range of 20 ± 5 W/m³, the optimal initial vvm should be between 0.01 and 0.005 m³/min for aeration pore sizes ranging from 1.0 mm down to 0.3 mm, respectively [6]. This integrated strategy ensures balanced oxygen transfer and CO₂ removal, leading to consistent and successful scale-up.

During the scale-up of bioreactor systems from laboratory to industrial production, a central challenge is the emergence of significant physical-chemical gradients. Parameters that are homogenous and tightly controlled in small-scale vessels, such as pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and substrate concentration, can become highly heterogeneous in large-scale tanks with working volumes of several hundred cubic meters [10] [11]. This inhomogeneity arises because mixing times increase with reactor volume, meaning cells circulating through the bioreactor experience oscillating microenvironments—a phenomenon often described as "bioreactor heterogeneity." [10] [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding, predicting, and troubleshooting these gradients is fundamental to optimizing scale-up processes, ensuring product consistency, and maintaining cell viability and productivity.

The table below summarizes the key gradients, their causes, and their direct impacts on the bioprocess.

Table 1: Critical Physical-Chemical Gradients in Bioreactor Scale-Up

| Gradient Type | Primary Cause in Large Bioreactors | Key Impact on Bioprocess |

|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | Increased mixing times leading to poor oxygen distribution; inefficient mass transfer from gas to liquid phase [1] [10]. | Oscillating between aerobic and oxygen-limited conditions can trigger metabolic shifts, reduce cell growth, and promote byproduct formation [10] [7]. |

| Substrate (e.g., Glucose) | Incomplete mixing creates zones of high and low nutrient concentration [10] [11]. | Cells experience feast-famine cycles, which can lead to reduced yield, metabolic stress, and the production of overflow metabolites [10]. |

| pH | Inadequate mixing of base or acid addition points for pH control [1]. | Localized pH spikes or dips can harm cell viability and enzyme activity, leading to inconsistent product quality [1]. |

| Temperature | Inefficient heat transfer and removal from exothermic bioreactions in larger volumes [1]. | Temperature spikes can denature proteins and adversely affect cell viability and productivity [1]. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do gradients form during scale-up when conditions are perfectly controlled at the lab scale? The formation of gradients is a direct physical consequence of increased reactor size. While a small 2L bioreactor can achieve near-instantaneous homogeneity, mixing times in large production-scale reactors can extend to several minutes [10] [11]. During this mixing time, cells travel through different zones—some close to the nutrient feed or oxygen sparger, others further away. This results in individual cells experiencing continuous oscillations in dissolved oxygen and substrate concentration, a condition not present in well-mixed lab-scale systems [10].

FAQ 2: My process shows good yield at the 5L scale but suffers from reduced productivity and increased byproducts at the 5000L scale. Could substrate gradients be the cause? Yes, this is a classic symptom of substrate inhomogeneity. In a large tank, cells repeatedly move between a substrate-limited zone (the bulk liquid) and a substrate-excess zone (near the feed point) [10] [11]. This "feast-famine" cycle can cause rapid turnover of side products and intermediate acidification of the medium, which in turn can reduce overall productivity and impact product quality [10]. Implementing a scale-down model that simulates these oscillations is the best way to confirm this and develop a robust solution.

FAQ 3: What is the most critical parameter for ensuring successful scale-up in aerobic fermentations? Gas-liquid mass transfer, specifically the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa), is often the most critical bottleneck [7]. The poor solubility of oxygen in fermentation broth means that efficiently supplying enough dissolved oxygen to cells at high densities is a major challenge. While kLa is easily maintained at a high level in small vessels through agitation and sparging, it becomes much harder to achieve in large-scale bioreactors, leading to dissolved oxygen gradients [1] [7].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Gradient-Related Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Product Yield & Metabolite Byproducts | Substrate gradients causing feast-famine cycles and metabolic overflow [10]. | - Switch to a fed-batch strategy with controlled feeding [12]. - Optimize feed point location and number to enhance distribution [1]. - Use scale-down models to test robustness of your microbial strain [10] [12]. |

| Poor Cell Growth & Viability | Dissolved oxygen gradients or prolonged periods of oxygen limitation [1] [7]. | - Optimize impeller design (e.g., Rushton turbines) and agitation speed for better oxygen dispersion [1] [12]. - Improve sparger design (e.g., use micro-spargers) to decrease bubble size and increase kLa [1] [7]. - Consider increasing reactor pressure to enhance oxygen solubility [7]. |

| Inconsistent Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility | Uncontrolled gradients leading to variable process performance; inadequate process control strategies [12]. | - Implement advanced process control with real-time monitoring and feedback loops for DO and pH [1] [12]. - Standardize vessel geometry and control systems across scales for better predictability [12]. - Apply rigorous cleaning and sterilization protocols to eliminate contamination as a variable [12]. |

| Failed Scale-Up Despite Similar kLa | Differences in the micro-environments (shear, mixing time) not captured by kLa alone [1]. | - Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling to predict and analyze fluid flow, shear, and concentration fields [1] [7]. - Perform scale-down studies using two-compartment bioreactors to simulate large-scale heterogeneities early in process development [10] [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Gradient Analysis

Protocol: Two-Compartment Scale-Down Study for Assessing Robustness

This methodology is used to simulate the substrate and dissolved oxygen oscillations experienced in large bioreactors, allowing for the assessment of microbial strain robustness and process performance [10] [11].

1. Principle: A scale-down system mimics the environment of a production-scale bioreactor by physically separating a well-mixed, aerobic stirred-tank compartment from a non-aerated plug-flow compartment. Cells continuously circulate between these two zones, experiencing the dissolved oxygen and substrate oscillations representative of large-scale conditions [10].

2. Equipment and Setup:

- Stirred-Tank Reactor (STR): Serves as the main, aerobic, and substrate-limited compartment. Equip with standard DO, pH, and temperature probes and controls.

- Plug-Flow Reactor (PFR) or Recirculation Loop: A non-aerated tube or vessel that creates a defined residence time where cells experience substrate excess and oxygen depletion.

- Peristaltic Pumps: To maintain a continuous, calibrated flow of culture between the STR and PFR.

- Analytical Tools: HPLC or other methods for substrate and metabolite analysis; capability for proteome, metabolome, and transcriptome sampling if required [10].

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Inoculate and run the fermentation in the STR compartment under standard, well-mixed, substrate-limited fed-batch conditions.

- Step 2: Activate the recirculation pump to divert a portion of the culture through the PFR. The residence time in the PFR (typically several minutes) is critical and should be calculated based on the mixing time of the large-scale reactor being modeled [10] [11].

- Step 3: Monitor key parameters (e.g., biomass, product titer, byproduct formation) in the STR over time.

- Step 4: Compare the results from the scale-down experiment with a control experiment run in a single, well-mixed STR. Significant deviations in productivity, growth, or metabolite profile indicate sensitivity to gradients [10].

Protocol: Determining Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa)

The kLa is a critical parameter for evaluating a bioreactor's oxygen delivery capacity [7].

1. Principle: The dynamic method involves measuring the rate at which dissolved oxygen increases in the liquid after the oxygen in the headspace has been purged with nitrogen.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Calibrate the dissolved oxygen probe.

- Step 2: Sparge the fermentation medium with nitrogen until the DO level drops to zero.

- Step 3: Stop the nitrogen flow and initiate aeration and agitation at the desired setpoints.

- Step 4: Record the DO concentration as a function of time until it reaches a steady state.

- Step 5: Plot the natural logarithm of (1 - DO/DO) versus time, where DO is the saturation concentration. The slope of the linear region of this plot is the kLa (h⁻¹).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Gradient Analysis and Scale-Up

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Specific Example / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Compartment Bioreactor System | Physically simulates substrate and DO oscillations for scale-down studies [10] [11]. | A stirred-tank reactor coupled with a plug-flow reactor; residence time in the PFR is a key design parameter. |

| Advanced Process Control Software | Enables real-time monitoring and automated feedback control of DO, pH, and feeding [1] [12]. | Software like INFORS HT's eve that manages parameters via automated feedback loops to maintain consistency [12]. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | Models fluid flow, predicts gradients (velocity, concentration), and identifies dead zones in silico [7]. | Used to optimize impeller and sparger design, and guide scale-up strategies, reducing empirical testing [7]. |

| High-Quality Sensor Probes | Accurate, real-time measurement of critical process parameters (pH, DO, temperature). | Use the same number and type of sensors at small scale as in large-scale systems to streamline scale-up [12]. |

| Robust Microbial Strains | Strains genetically stable and resilient to process inhomogeneities. | Corynebacterium glutamicum DM1933 has shown remarkable robustness against DO/substrate oscillations [10] [11]. |

Visualization of Gradient Impacts and Analysis

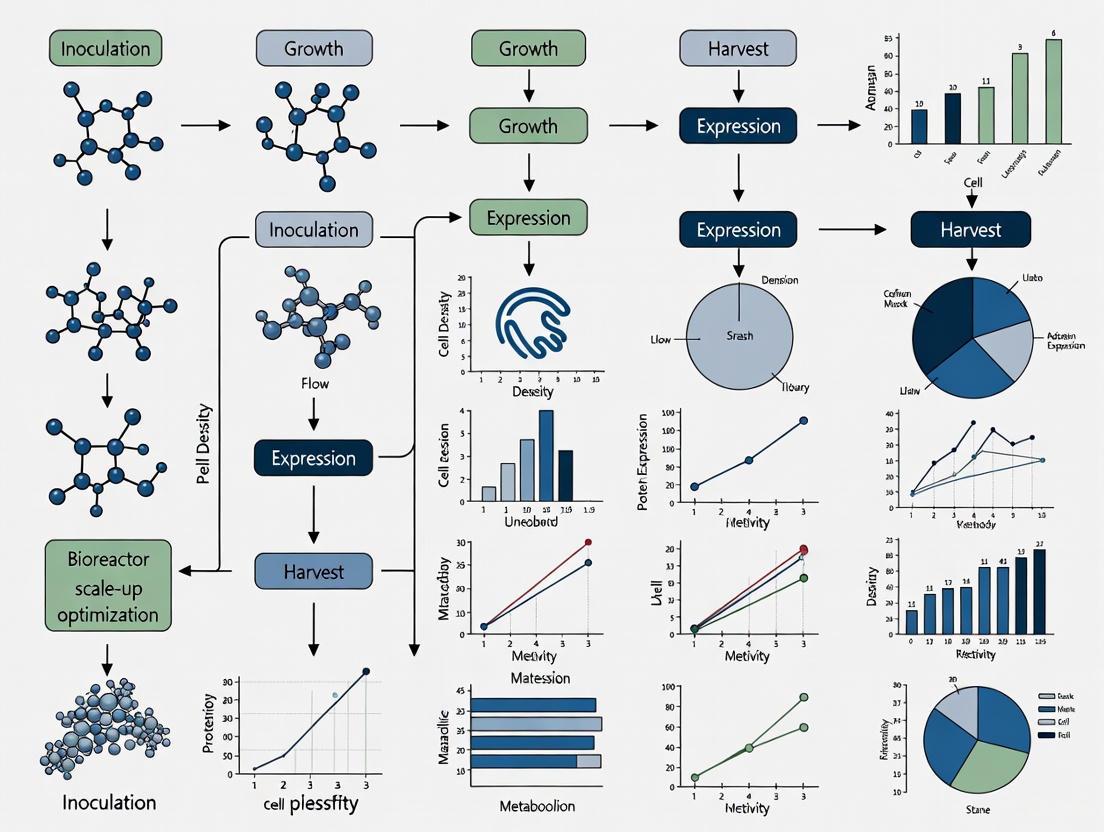

The following diagrams, created using the specified color palette, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows related to physical-chemical gradients.

Diagram 1: Bioreactor Gradient Formation and Cellular Experience

Diagram 2: Two-Compartment Scale-Down Experiment Workflow

FAQs: Bioreactor Scale-Up and Cell Physiology

How do hydrodynamic conditions in a large-scale bioreactor directly impact cell health? The agitation and aeration necessary for mixing and oxygen transfer in a large-scale bioreactor create hydrodynamic forces, primarily shear stress. Excessive shear stress can cause direct mechanical damage to cells, leading to reduced viability and productivity. Furthermore, it can induce subtle physiological changes, such as altered metabolism and increased early apoptosis, even in the absence of immediate cell death. Optimizing parameters like agitation speed is therefore critical to balance efficient mass transfer with the maintenance of cell integrity [13] [14].

What are the common signs of contamination in a bioreactor, and how can it be prevented? Early detection of contamination is key to minimizing losses. Common signs include:

- Unusual changes in culture color (e.g., a pH indicator like phenol red turning from pink to yellow due to acid formation).

- Earlier-than-expected growth or unexpected changes in culture turbidity, density, or smell.

- Poor cell growth and performance, which may be the only clue for "hidden" contaminants like mycoplasma or viruses.

Prevention involves a multi-pronged approach: rigorous checking and replacement of O-rings, validation of sterilization cycles (e.g., using temperature sensors in the vessel during autoclaving), employing secure inoculation techniques instead of "aseptic pours," and ensuring all lines and components are properly cleaned and assembled [15].

From a metabolic perspective, how does scale-up influence a cell's physiological state? Advanced multi-omics analyses reveal that scale-up is not merely a physical challenge but a metabolic one. Research on Vero cells has shown that culture in a controlled bioreactor environment, compared to a simulated natural state, can lead to a more metabolically active cell population. Specifically, transcriptomics and proteomics have identified significantly increased levels of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase and DNA replication licensing factors, while metabolomics shows an increase in metabolites like arachidonic acid. This indicates that successful scale-up can enhance DNA replication, protein translation, and overall metabolic activity, making cells more conducive to amplification and target product production [13].

Why is the carbon source composition important during scale-up? The composition and physical form of the carbon source directly affect substrate accessibility and metabolic pathways. For example, in the production of cellulase, using a specific 3:1 ratio of Avicel to cellulose was shown to significantly accelerate enzyme production, reaching peak activity days earlier than with Avicel alone. This optimization at the flask scale successfully translated to a 10 L bioreactor, resulting in a two-fold increase in filter paper unit (FPU) activity. This demonstrates that fine-tuning nutrient composition is a fundamental step in developing a robust and efficient scaled-up process [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Sudden Drop in Product Yield or Cell Viability

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Shear Stress | - Analyze recent changes to agitation speed/impeller design.- Check for cell debris or a decrease in cell viability counts.- Conduct transcriptomic analysis for shear-stress markers. | - Reduce agitation speed to the minimum required for adequate mixing and oxygen transfer.- Consider using a bioreactor with a lower-shear impeller or an airlift system for sensitive cells [14] [16]. |

| Sub-Optimal Nutrient Composition | - Review batch records for any changes in media composition.- Measure residual substrate levels and metabolic by-products.- Compare growth and production profiles with historical data. | - Re-optimize carbon or nitrogen source ratios in a scaled-down model [14].- Implement a controlled fed-batch strategy to maintain optimal nutrient levels. |

| Undetected Contamination | - Sample and plate culture on rich growth medium.- Check for color change, turbidity, or smell.- Use microscopy, Gram staining, or specific test kits for mycoplasma [15]. | - Discard the contaminated batch immediately.- Identify and sterilize the contamination source (check O-rings, seals, tubing, inoculation protocols) [15]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Performance Between Scales

| Scale-Down Parameter | Target Cell Physiology Metric | Experimental Protocol for Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Agitation Speed | Viability, Cell Damage, Enzyme Activity | 1. In a bench-top bioreactor, test a range of agitation speeds (e.g., 150, 180, 210 rpm) [14].2. Measure cell viability and product titer (e.g., EG, BGL, CBH activity for enzymes) over time [14].3. Select the speed that maximizes yield while minimizing shear damage. |

| Oxygen Transfer Rate | Growth Rate, Metabolite Profile | 1. Correlate the kLa (volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient) from the production scale to the bench scale.2. Adjust aeration rate and agitation to match the kLa.3. Analyze dissolved oxygen levels and metabolic by-products to ensure physiological equivalence. |

| Carbon Source Mix | Metabolic Activity, Production Time | 1. Test different ratios of carbon substrates (e.g., Avicel:cellulose from 4:0 to 0:4) in shake flasks [14].2. Measure the time to peak product activity and total yield.3. Scale the optimal ratio to a bioreactor for validation [14]. |

Key Parameter Impact and Experimental Data

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from scale-up optimization studies, highlighting how different parameters affect key cellular outputs.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Bioreactor Conditions on Cell Physiology and Output [14]

| Parameter Tested | Condition | Key Outcome: Endoglucanase (EG) Activity (U/mL) | Key Outcome: β-Glucosidase (BGL) Activity (U/mL) | Key Outcome: Protein Concentration (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Source (Avicel:Cellulose) | A3C1 (3:1 Ratio) | 27.84 ± 3.29 | 0.87 ± 0.14 | 0.68 ± 0.19 |

| A4C0 (Control) | 24.19 ± 5.18 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.09 | |

| Agitation Speed | 180 rpm | 32.04 ± 3.82 | 3.60 ± 0.69 | 1.05 ± 0.07 |

| 150 rpm | 16.90 ± 2.12 | 1.77 ± 0.42 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | |

| Turbulence & Additive | Baffled Flask + 1% Biochar | 34.41 ± 3.02 | 1.46 ± 0.15 | 0.97 ± 0.03 |

| Baffled Flask, No Biochar | 27.59 ± 3.03 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.04 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Bioreactor Process Optimization

| Item | Function in Bioreactor Research |

|---|---|

| Avicel & Cellulose | Model carbon sources used to study and optimize the metabolism of lignocellulosic substrates, crucial for enzyme production and biofuel research [14]. |

| Biochar | An additive with high porosity and surface area that can enhance microbial growth and cellulase activity by serving as a microbial habitat, often showing synergistic effects with turbulence [14]. |

| Specific Substrates (e.g., pNPC, pNPG) | Synthetic substrates used in enzymatic assays to quantitatively measure the activity of specific enzymes like cellobiohydrolase (CBH) and β-glucosidase (BGL) [14]. |

| Process Control Buffers & Acids/Bases | Essential for maintaining a constant pH in the bioreactor, a critical environmental parameter that strongly influences cell growth and metabolic productivity [17] [16]. |

| Cell Viability Assays (e.g., Trypan Blue) | Dyes used to distinguish between live and dead cells, providing a fundamental metric for assessing culture health and the impact of bioreactor conditions. |

| Metabolomics Kits | Kits for analyzing intracellular and extracellular metabolites, enabling a systems-level understanding of how bioreactor conditions alter the cell's metabolic state [13]. |

Experimental Workflow and Cell Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams outline the experimental workflow for scaling up a bioprocess and the subsequent cellular response to the bioreactor environment.

Bioreactor Scale-Up Workflow

Cell Response to Bioreactor Environment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical KPIs to monitor when scaling up a biomass conversion process? The most critical KPIs form a cascade, starting with biomass indicators, moving to environmental parameters, and culminating in final product metrics [1] [18] [19]. Primary biomass KPIs include Viable Cell Concentration (VCC), Viable Cell Volume (VCV), and Wet Cell Weight (WCW) [18]. Essential environmental parameters are dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, temperature, and nutrient levels[ citation:1]. The ultimate KPI is the Product Titer, which quantifies the final concentration of your target molecule (e.g., g/L of lipid or antibody) [20] [19].

Q2: Why does my product titer drop at larger scales even when VCC appears similar to lab scale? A drop in titer despite similar VCC often signals an issue with cell physiology or environmental heterogeneity [1] [19]. At large scales, inadequate mixing can create gradients in nutrients, pH, and dissolved oxygen. While total cell count might be the same, cells experience suboptimal conditions that impact their productivity. Furthermore, traditional VCC measurements may not reflect changes in cell size or metabolic activity. Tracking Viable Cell Volume (VCV) via capacitance sensors can be a more robust KPI, as it accounts for cell size and better reflects the biologically active cell mass [18].

Q3: How can I monitor biomass in real-time to improve process control during scale-up? In-line capacitance sensors are a key PAT (Process Analytical Technology) tool for real-time biomass monitoring [18]. These sensors work by measuring the permittivity of the culture broth, which correlates with the volume of viable cells (VCV) because only cells with intact membranes polarize in an electric field [18]. You can develop scale-independent linear regression models to predict VCC, VCV, and WCW from the capacitance signal, enabling immediate feedback and control [18].

Q4: What are common root causes for low product titer in a scaled-up bioreactor? Low titer at scale typically stems from several interconnected issues [1] [19]:

- Mass Transfer Limitations: Inefficient oxygen transfer (low kLa) is a common bottleneck, especially in high-density cultures [1] [7].

- Environmental Gradients: Large bioreactors can have zones of different pH, nutrient, or metabolite concentrations, leading to a heterogeneous cell population with reduced average productivity [1] [19].

- Shear Stress: Increased agitation and aeration can damage cells or disrupt aggregates, negatively impacting growth and product formation [21] [19].

- Genetic and Phenotypic Instability: Prolonged cultivation times during scale-up can exert selective pressures, leading to a population drift toward lower-producing phenotypes [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Final Product Titer

Problem: The concentration of the target product (e.g., antibody, lipid, biofuel) is significantly lower in the pilot or production-scale bioreactor compared to the lab-scale system.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Oxygen Transfer | Measure the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa) at large scale. Compare oxygen uptake rates (OUR) between scales. | Optimize impeller design and sparger configuration (e.g., use smaller bubbles). Increase agitation or aeration rates within shear stress limits [1] [7]. |

| Nutrient Gradients | Take samples from different zones of the bioreactor and measure nutrient (e.g., glucose, ammonium) concentrations. | Improve mixing efficiency, potentially by revising impeller design or using baffles. Implement fed-batch strategies to avoid high initial nutrient concentrations [1] [20]. |

| Shear-Induced Damage | Monitor cell viability and lysis products (e.g., LDH). Check for a discrepancy between VCC and VCV trends [18]. | Evaluate and add protective media additives like Pluronic F68 or PEG [21]. Adjust impeller type to a more shear-sensitive design (e.g., pitched-blade instead of Rushton) [5]. |

| Genetic Instability of Production Cell Line | Perform single-cell cloning and productivity assays on cells sampled from the end of the production run. | Improve cell line development by screening for genetically stable clones. Shorten the seed train or production culture duration to minimize population drift [19]. |

Inconsistent Biomass Measurements

Problem: Offline biomass measurements (e.g., VCC) do not align with online sensor readings or show high variability between batches.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Error | Ensure sampling port is well-mixed and representative. Compare samples from multiple ports if available. | Standardize sampling procedures: flush ports thoroughly, take consistent sample volumes, and process samples immediately [18] [20]. |

| Sensor Fouling or Calibration Drift | Perform manual offline measurements to calibrate and validate the online sensor signal. Check for biofilm formation on the sensor probe. | Establish a regular sensor calibration and maintenance schedule. Use sensors with clean-in-place (CIP) capabilities [5]. |

| Changes in Cell Physiology | Compare the cell size distribution (e.g., via microscopy or automated cell counters) between phases of the process where the discrepancy occurs. | For capacitance sensors, shift the KPI focus from VCC to Viable Cell Volume (VCV), which is more directly measured and robust to physiological changes [18]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Online Biomass Monitoring Using Capacitance Sensors

Objective: To establish a scalable linear regression model for predicting viable biomass in real-time during bioreactor cultivation [18].

Materials:

- Bioreactor equipped with an in-line capacitance sensor (e.g., "Fogale" or similar).

- Cell culture (e.g., CHO cells, microbial culture).

- Offline cell analyzer (e.g., automated cell counter, flow cytometer).

- Centrifuge and equipment for wet cell weight (WCW) measurement.

Methodology:

- Sensor Installation and Calibration: Install the capacitance sensor according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Initialize the system and set the measurement frequency (typically in the range of 0.5 - 1.5 MHz for mammalian cells).

- Parallel Data Collection: Throughout the bioreactor run, record the online capacitance signal (in pF/cm) at regular intervals (e.g., every minute).

- Offline Sampling and Analysis: Simultaneously, take representative samples from the bioreactor at key process phases (e.g., every 12-24 hours). From each sample, perform offline measurements of:

- Viable Cell Concentration (VCC) using a cell counter with Trypan Blue exclusion.

- Cell diameter (to calculate Viable Cell Volume, VCV).

- Wet Cell Weight (WCW) via centrifugation.

- Model Development: After the run, plot the offline measurements (VCC, VCV, WCW) against the online capacitance signal collected at the corresponding times.

- Linear Regression: Perform a linear regression analysis to generate a model (e.g.,

VCC = a * Capacitance + b). Validate the model's accuracy using the coefficient of determination (R²). This model can then be used to predict biomass in subsequent runs in real-time [18].

Protocol: Statistical Optimization for Enhanced Product Titer

Objective: To systematically optimize critical process parameters to maximize product titer using Response Surface Methodology (RSM), as demonstrated in microbial oil production [20].

Materials:

- Shake flasks or lab-scale bioreactors.

- Culture medium and production strain.

- Analytical equipment for product quantification (e.g., GC for lipids, HPLC for antibodies).

Methodology:

- Screening (Plackett-Burman Design): Identify critical factors (e.g., carbon source concentration, pH, temperature, nitrogen source) influencing product titer. Use a Plackett-Burman design to screen a wide range of factors with a minimal number of experimental runs. This distinguishes significant factors from insignificant ones.

- Optimization (Box-Behnken Design): Take the most significant factors (typically 3-4) identified in the screening step and design a Box-Behnken experiment. This design fits a quadratic surface to the data, which can identify optimal factor levels and interaction effects.

- Bioreactor Validation: Transfer the optimized conditions from the shake flasks to a controlled lab-scale bioreactor (e.g., 7 L). Validate the model's prediction by running the process at the calculated optimum and measuring the final product titer [20].

- Fed-Batch Strategy: To further boost titer, implement a fed-batch strategy in the bioreactor based on the optimized parameters, feeding nutrients to maintain optimal concentrations and prevent repression [20].

The workflow below visualizes this multi-stage optimization and scale-up process.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for statistical optimization of product titer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in advanced bioreactor scale-up experiments, as cited in the literature.

| Item | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Capacitance Sensor | In-line, real-time monitoring of viable biomass (VCV) [18]. | Used to track CHO cell growth across scales (50L - 2000L) for consistent process monitoring [18]. |

| Pluronic F68 | Non-ionic surfactant that protects cells from shear stress in agitated bioreactors [21]. | Added to hiPSC suspension cultures to reduce shear-induced cell death and improve aggregate stability [21]. |

| Heparin Sodium Salt (HS) | Polyanionic additive that can prevent unwanted cell aggregation and fusion [21]. | Used in a DoE study to control hiPSC aggregate size and stability in vertical wheel bioreactors [21]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer used to modulate cell aggregation and reduce surface tension [21]. | Optimized in concert with Heparin to limit hiPSC aggregate fusion, allowing for reduced bioreactor agitation speed [21]. |

| Rhodamine B / Sudan Black B | Lipid-soluble dyes for staining and visualizing intracellular lipid droplets [20]. | Employed for the initial screening and selection of high-lipid-producing strains of Rhodotorula glutinis [20]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Statistical software for designing efficient experiments and modeling complex factor interactions [21] [20]. | Used to optimize media compositions (e.g., for hiPSCs) and fermentation parameters (e.g., for microbial oil) with minimal experimental runs [21] [20]. |

Advanced Monitoring & Control Pathways

Integrating real-time data from sensors like capacitance probes into a control strategy is the pinnacle of scale-up optimization. The following diagram illustrates this closed-loop control pathway for maintaining a critical process parameter.

Diagram 2: Real-time KPI monitoring and control loop.

Advanced Scale-Up and Scale-Down Methodologies: Practical Frameworks for Predictive Modeling

Core Concepts: Why Scale-Down Systems Are Needed

During the scale-up of a bioprocess from laboratory to industrial scale, not all characteristics can be kept constant. A key consequence is that mixing times increase with larger reactor volumes [22] [23]. In small-scale bioreactors, mixing is highly efficient with mixing times of less than 5 seconds, preventing gradient formation. In contrast, mixing times in large-scale bioreactors can range from tens to hundreds of seconds [22].

This inadequate mixing leads to the formation of concentration gradients of critical process parameters like substrates (e.g., glucose), dissolved oxygen (DO), and pH [22] [23]. Cells circulating through the bioreactor are therefore exposed to rapidly fluctuating environmental conditions, which can:

- Trigger phenotypic population heterogeneity, where single cells within an isogenic population respond differently to the fluctuations [22].

- Decrease key performance indicators (KPIs), such as reduced productivity, increased byproduct formation, and decreased biomass yield [22]. For example, scaling an E. coli process from 3 L to 9000 L led to a 20% reduction in biomass yield [22].

Scale-down bioreactors are lab-scale systems designed to mimic these large-scale gradients in a controlled and cost-effective manner, allowing researchers to preemptively identify and solve scale-up challenges [22].

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common gradients in large-scale bioreactors, and which should I prioritize in my scale-down model? A: The most common and impactful gradients are substrate concentration and dissolved oxygen (DO) [22]. You should prioritize these in your initial model, especially if your microorganism has a high specific substrate consumption rate or if you are using a concentrated feed solution. Gradients of pH, temperature, and dissolved carbon dioxide are also present and can be investigated subsequently [22].

Q2: My scale-down model shows reduced product yield compared to the homogeneous lab-scale process. What is the likely cause? A: This is a classic sign of gradient-induced stress. Exposure to substrate gradients can cause overflow metabolism, where cells in high-substrate zones rapidly consume nutrients, leading to byproduct formation (e.g., acetate in E. coli cultures) [22]. Furthermore, repeated cycling between oxygen-rich and oxygen-limited zones can force metabolic shifts that reduce the overall efficiency and product yield [22].

Q3: How can I control aggregate size and stability in a suspension culture of stem cells within a bioreactor? A: Controlling aggregate fusion is critical for homogeneous growth and differentiation. A Design of Experiments (DoE) approach has successfully identified that the interaction of media additives like Heparin (HS) and Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) can limit aggregation and improve stability [24] [25]. This control allows for a decrease in bioreactor impeller speed, thereby reducing shear stress on the cells during large-scale expansion [25].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Area | Specific Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Establishment | Unable to replicate theoretical mixing time or concentration profiles. | - Incorrect reactor compartment volume ratio.- Fluctuating flow rates between compartments. | - Validate circulation pump calibration.- Use tracer studies to confirm mixing time and adjust compartment sizes [22]. |

| Process Performance | Decreased biomass yield or increased byproduct formation in scale-down system. | Cells experiencing repeated feast/famine cycles or oxygen limitation, triggering overflow metabolism [22]. | - Analyze byproduct levels (e.g., acetate, lactate).- Consider multi-point substrate feeding strategy for large-scale design [22]. |

| Contamination | - Unexpected early growth.- Culture medium changes color (e.g., yellow in phenol red).- Increase in turbidity [15]. | - Compromised seed train or inoculation technique.- Failed sterilization (e.g., damaged O-rings, autoclave issues).- Wet exit gas filter allowing microbial grow-through [15]. | - Check inoculum by re-plating on rich medium.- Replace O-rings (every 10-20 cycles) and verify autoclave temperature with a sensor.- Ensure efficient gas cooling and do not exceed 1.5 VVM air flow [15]. |

| Cell Culture / hiPSCs | Excessive aggregate fusion, leading to heterogeneous cell populations. | - Media composition not optimized for suspension culture.- High bioreactor shear stress. | - Supplement media with additives like Heparin and PEG to improve aggregate stability [25].- Use DoE to optimize additive concentrations for stability vs. growth [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Scale-Down Studies

Establishing a Two-Compartment System for Gradient Simulation

This protocol outlines the setup for a widely used scale-down configuration that separates a well-mixed "bulk" zone from a "feed" or "high-stress" zone [22].

1. Principle: A two-compartment system physically separates a stirred-tank reactor (STR), representing the well-mixed bulk of a large tank, from a plug-flow reactor (PFR) or another connected vessel, which simulates a poorly mixed region like the feed zone. Cells continuously circulate between these two zones, experiencing dynamic changes in substrate and oxygen levels [22].

2. Apparatus and Setup:

- Stirred-Tank Reactor (STR): A standard lab-scale bioreactor (e.g., 1-5 L) with controls for pH, DO, and temperature.

- Plug-Flow Reactor (PFR): A long, coiled tube or a small, non-aerated vessel. The volume ratio between the PFR and STR should be designed to mimic the estimated volume fraction of the gradient zone in the large-scale process (often around 10%) [22].

- Peristaltic Pumps (x2): One pump to transfer broth from the STR to the PFR, and a second to return it from the PFR to the STR. The combined flow rate determines the circulation time, which should match the mixing time of the large-scale bioreactor.

- Tubing and Connectors: Sterile, sanitary connectors to link the systems.

3. Critical Operational Parameters:

- Circulation Time: Set the pump flow rates so that the total circulation time of the fluid equals the mixing time (θ95) of the target large-scale bioreactor.

- Volume Ratio: The PFR volume should typically be 5-15% of the total working volume, representing the substrate feed zone [22].

- Environmental Control: Maintain dissolved oxygen and pH in the STR at setpoints. The PFR may be designed to become substrate-rich and oxygen-limited.

Diagram 1: Two-compartment scale-down system

Protocol: Using a DoE to Optimize hiPSC Aggregate Stability

This methodology is adapted from research demonstrating control over human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) aggregates in vertical wheel bioreactors [25].

1. Principle: A Design of Experiments (DoE) approach systematically evaluates the effect of multiple media additives and their interactions on cell growth, pluripotency maintenance, and aggregate stability, generating mathematical models to find optimal conditions [25].

2. Experimental Design:

- Factors: Select 5 media additives known to influence stability: Heparin sodium salt (HS), Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA), Pluronic F68, and Dextran sulfate (DS).

- Concentration Ranges: Define ranges based on literature (e.g., 0.1-1 mg/mL for HS; 0.5-2% for PEG).

- DoE Model: Use a D-optimal interaction design via software (e.g., MODDE). A design with 16 unique reaction conditions plus 3 center point replicates is effective.

- Response Variables:

- Growth Rate: Daily cell count via flow cytometry after aggregate dissociation. Calculate doubling time.

- Pluripotency Maintenance: Flow cytometry analysis for markers OCT4 and SOX2 (target >90% positive).

- Aggregate Stability: Mean aggregate size and distribution measured daily from bright-field images using ImageJ.

3. Procedure:

- Culture hiPSCs to 60-70% confluence in vitronectin-coated plates.

- Dissociate cells with TrypLE and resuspend in E8 medium with 10 µM Y-27632 ROCK inhibitor.

- Seed 11 million cells into a 100 mL vertical wheel bioreactor.

- Prepare the 19 different media combinations as per the DoE layout.

- Sample daily (3 x 1 mL for cell count and 500 µL for imaging).

- Analyze cell count and aggregate size data, then input into DoE software to generate predictive models.

- Validate the optimized media formulation in a new bioreactor run.

Quantitative Data for Process Design

Key Parameters for Scale-Down Simulation

| Parameter | Laboratory Scale (0.5-10 L) | Large Industrial Scale (e.g., 100 m³) | Scale-Down Simulation Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing Time (θ₉₅) | Very short (< 5 seconds) [22] | Long (10s to 100s of seconds) [22] | Match large-scale mixing time via pump rates in a multi-compartment system [22]. |

| Substrate Gradient | Negligible [22] | Significant (e.g., 10-fold difference from feed point to bottom) [22] | Create distinct zones (excess, limitation, starvation) and control cell exposure time [22]. |

| Cell Circulation | N/A | Stochastic, based on fluid flow | Simulate with a circulation time equal to large-scale mixing time [22]. |

Impact of Scale-Down Conditions on Process Output

| Organism / Cell Type | Scale-Down Condition | Impact on Key Performance Indicator (KPI) | Change vs. Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Baker's Yeast) | Mimicking 120 m³ process in a 10 L scale-down system [22] | Final Biomass Concentration | +7% increase [22] |

| Escherichia coli (for β-galactosidase) | Scale-up from 3 L to 9000 L | Biomass Yield (YX/S) | -20% reduction (Highlighting the problem scale-down aims to solve) [22] |

| Human iPSCs | Supplementing E8 medium with optimized Heparin & PEG combination [25] | Expansion Doubling Time | ~40% shorter than E8 medium alone [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Key Media Additives for hiPSC Bioreactor Culture

| Reagent | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Heparin Sodium Salt (HS) | Enhances aggregate stability and limits fusion by interacting with extracellular matrix components; improves maintenance capacity and expansion [25]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Reduces unwanted cell adhesion and aggregate fusion; critical for maintaining pluripotency and controlling aggregate size in suspension [25]. |

| Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | Used in media optimization to support cell growth and expansion, often in combination with other additives [25]. |

| Pluronic F68 | Protects cells from shear stress by reducing surface tension of the media, a common challenge in stirred-tank bioreactors [25]. |

| Dextran Sulfate (DS) | Evaluated for its properties in enhancing aggregate stability and modulating cell-cell interactions in 3D suspension culture [25]. |

Analytical Methods for System Characterization

| Method | Application | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | Models fluid flow and gradient formation in large-scale bioreactors [22]. | Identifies potential problem zones and informs scale-down reactor design. |

| Compartment Modeling | Subdivides a large bioreactor into interconnected, ideally mixed zones [22]. | Allows for faster, simplified simulation of large-scale flow patterns. |

| Lifeline Analysis | Models the dynamic conditions (substrate, O₂) experienced by a single cell as it circulates [22]. | Provides a "cell's-eye view" of the process, crucial for predicting physiologic response. |

| Tracer Studies | Measures the mixing time in a bioreactor by tracking the homogenization of an added tracer [22]. | Validates that the scale-down system accurately replicates large-scale mixing efficiency. |

Diagram 2: Scale-down problem-solving workflow

Leveraging Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Predicting Flow and Mixing in Large Bioreactors

Troubleshooting Guide: Common CFD Challenges in Bioreactor Scale-Up

FAQ: What are the most common issues when using CFD for bioreactor scale-up and how can they be addressed? Bioreactor scale-up presents unique challenges where complete physical similarity between small and large scales is impossible to achieve [26]. CFD is a powerful tool for identifying and overcoming these issues. The table below summarizes common problems, their underlying causes, and potential solutions.

| Common Issue | Root Cause | Potential CFD-Driven Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Dead Zones / Stagnant Areas [27] | Inadequate flow patterns; low turbulence; incorrect impeller configuration or baffle design [27]. | Modify impeller type, size, or placement; adjust baffle design; optimize agitation rate [27]. |

| Poor Oxygen Mass Transfer (Low kLa) [27] [28] | Inefficient gas dispersion; suboptimal bubble size; low gas holdup; flooded impeller [27]. | Optimize sparger design (e.g., switch to a ring sparger); adjust sparger-to-impeller diameter ratio (~0.8 found optimal) [28]; increase impeller speed or gas flow rate [28]. |

| Vortex Formation [27] | Inadequate baffling at high rotational speeds [27]. | Use CFD to validate baffle design and placement to break up vortex formation [27]. |

| High Shear Rates [27] [29] | Excessive power input at the impeller tip; small eddy sizes [29]. | Model shear stress and eddy size (Kolmogorov scale); reduce agitation speed; change to a low-shear impeller [27]. |

| Inhomogeneous Mixing [27] [30] | Insufficient mixing time; poor axial flow [27]. | Use transient tracer simulations to determine 95% homogeneity mixing time; optimize impeller configuration for better radial/axial flow patterns [27]. |

Experimental Protocols: CFD Model Setup and Validation

FAQ: What is a robust methodology for setting up and validating a CFD model of a stirred-tank bioreactor? A validated CFD model is crucial for reliable scale-up predictions. The following protocol outlines a multi-phase approach, coupling hydrodynamics with mass transfer.

Step 1: Geometry Creation and Mesh Generation

- Action: Create a 3D computer-assisted design (CAD) model of the bioreactor, including the tank, baffles, impeller(s), and sparger [27].

- Protocol: The computational domain is discretized into a mesh of small control volumes. Mesh quality is critical; a grid independence study must be conducted to ensure results do not change significantly with a finer mesh [31].

Step 2: Model Selection and Setup

- Action: Select appropriate physical models based on the flow regime and phases involved.

- Protocol:

- Flow Framework: Use a Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) for steady-state simulations or Sliding Mesh (SM) for transient, more accurate impeller rotation modeling [32].

- Turbulence Model: For most engineering applications, the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) models (e.g., k-ε) are used. For capturing complex, instantaneous vortex structures, Large Eddy Simulation (LES) is more accurate but computationally expensive [33] [32].

- Multiphase Model: Use an Eulerian-Eulerian approach for gas-liquid systems [30] [32]. Couple this with a Population Balance Model (PBM) to simulate bubble coalescence and breakage, which is essential for predicting accurate bubble size distributions and the oxygen mass transfer coefficient (kLa) [30] [28].

Step 3: Solver Execution and Convergence

- Action: Run the simulation until the solution fields (velocity, pressure) stabilize.

- Protocol: Solve the discretized conservation equations for mass and momentum. For transient cases, time-averaging instantaneous solutions over a sufficiently long period is necessary to achieve hydrodynamic convergence and statistical significance [33]. Monitor residual plots to ensure convergence.

Step 4: Model Validation with Experimental Data

- Action: Confirm the model's accuracy by comparing its predictions with empirical data.

- Protocol: The most common validation metric is the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa). Compare the simulated kLa value against experimentally measured kLa in the bioreactor under identical operating conditions [28]. Other validation data can include power number, mixing time, and particle image velocimetry (PIV) flow fields [31].

Step 5: Scenario Analysis and Optimization

- Action: Use the validated model to test "what-if" scenarios.

- Protocol: Systematically vary key parameters like impeller speed, sparger design, and gas flow rate to visualize their impact on mixing, shear, and kLa. This identifies the optimal operational window for scale-up [27] [28].

Engineering Parameters for Scale-Up

FAQ: Which engineering parameters should be monitored in CFD simulations to ensure successful bioreactor scale-up? During scale-up, it is impossible to keep all scaling criteria constant simultaneously, requiring strategic choices [26]. CFD simulations allow for the tracking of key parameters to guide this decision-making process. The table below lists critical parameters, their significance, and scaling considerations.

| Parameter | Significance in Bioreactor Performance | Scale-Up Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Power Input per Unit Volume (P/V) | Impacts mixing, shear stress, and eddy size [29]. | Often kept constant to maintain similar mixing intensity, but can lead to high shear at large scales [26]. |

| Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa) | Determines the rate of oxygen transfer from gas to liquid; often the limiting factor [30] [28]. | Must be maintained at a sufficient level to meet cell oxygen demand. CFD can correlate kLa to geometry (e.g., sparger/impeller ratio) and operating conditions [28]. |

| Mixing Time | Time required to achieve a specified degree of homogeneity (e.g., 95%) [27]. | Mixing times typically increase with scale. CFD tracer studies can predict large-scale mixing times and identify strategies for improvement [27]. |

| Impeller Tip Speed | Related to the maximum shear rate experienced by cells [29]. | Keeping it constant is a common scale-up rule to control shear, but may compromise mixing at larger scales [26]. |

| Reynolds Number (Re) | Determines whether flow is laminar, transitional, or turbulent [29]. | Flow in production-scale bioreactors is almost always turbulent. Re is useful for characterizing the flow regime at different scales [29]. |

| Kolmogorov Length Scale (λ) | The size of the smallest turbulent eddies [29]. | Calculated as (ν³/ε)^(1/4). If λ is larger than the cell, shear damage is unlikely. High power input (ε) creates smaller, more damaging eddies [29]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Models for CFD Analysis

This table details key "models" and inputs, which serve as the essential "reagents" for a successful CFD study.

| Tool/Model | Function & Explanation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| k-ε Turbulence Model | A RANS model that assumes isotropic turbulence. It is a robust and computationally efficient workhorse for simulating turbulent flow in bioreactors [32]. | Predicting the mean flow field and power consumption in a large-scale stirred tank [32]. |

| Population Balance Model (PBM) | Tracks how populations of bubbles change due to break-up and coalescence. Crucial for predicting accurate bubble size distributions, which directly impact kLa [30]. | Optimizing sparger design and gas flow rate to maximize oxygen transfer while minimizing foam [30] [28]. |

| Eulerian-Eulerian Framework | Treats different phases (e.g., liquid and gas bubbles) as interpenetrating continua. Essential for modeling the gas-liquid hydrodynamics in aerated bioreactors [30] [32]. | Simulating the distribution of gas hold-up and the path of air bubbles from the sparger through the reactor [30]. |

| Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) | A steady-state approach that models impeller rotation by applying a rotating frame of reference to the impeller region. It offers a good balance of accuracy and computational cost [32]. | Initial design and scoping studies to compare different impeller configurations. |

| Tracer Diffusion Simulation | A transient simulation that introduces a non-reacting tracer to visualize and quantify how quickly the bioreactor achieves homogeneity [27]. | Determining the mixing time required to reach 95% homogeneity for a given impeller speed and configuration [27]. |

Visualizing the CFD-Driven Scale-Up Strategy

The following diagram outlines the overarching logic of using CFD to de-risk and optimize the bioreactor scale-up process, integrating the elements discussed in this guide.

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address common challenges in bioreactor scale-up optimization. The content is framed within a broader thesis on applying systematic approaches, particularly Design of Experiments (DoE), to enhance process robustness and yield in bioprocessing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary statistical reason my process performs well at lab-scale but fails during scale-up? This is often due to an incomplete understanding of interaction effects between scale-dependent parameters (like oxygen transfer and shear stress) that are not apparent in simple, one-factor-at-a-time lab studies. A DoE approach systematically varies multiple factors simultaneously to build a predictive model of the process. This model identifies critical interactions—for instance, how agitation speed and sparger design jointly affect the oxygen transfer rate (kLa)—ensuring the process remains robust when these parameters change at larger scales [34] [2].

FAQ 2: How can I quickly identify the root cause of low product yield in a scaled-up bioreactor? Begin by investigating parameters that are known to scale non-linearly. A structured troubleshooting approach should prioritize:

- Oxygen Transfer: Measure the kLa value and compare it to your lab-scale bioreactor. Insufficient oxygen transfer is a common scale-up bottleneck [2].

- Mixing Heterogeneity: Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations to identify potential gradients in nutrients, pH, or dissolved oxygen. Experimentally, you can validate this by sampling from different ports in the large-scale vessel [34] [35].

- Shear Stress: Check cell viability and aggregate size distribution. Increased shear in large bioreactors can damage cells. Review your impeller type and agitation speed, potentially testing media additives like Pluronic F68 to protect cells [2] [21].

FAQ 3: My cell viability drops in a large-scale run. Is this a raw material or a process issue? While both are possible, process-related shear stress is a frequent culprit in scale-up. To distinguish between the two:

- Investigate Process Parameters: Analyze the power input per volume (P/V) and tip speed, as these increase with scale and can generate damaging shear forces [36].

- Analyze Raw Materials: If process parameters are ruled out, conduct a small-scale DoE study using the same raw materials to test for a media component interaction. Consistency in raw materials is critical, as variability can significantly impact process performance at any scale [2] [37].

FAQ 4: How can I ensure my scaled-up process meets regulatory quality standards? Implement Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts to demonstrate your process is in a state of statistical control. SPC charts differentiate between common cause (inherent) and special cause (assignable) variation. Consistently operating within control limits provides strong evidence of process robustness and consistency to regulatory bodies, which is as important as meeting final product specifications [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Product Titer After Scale-Up

A drop in titer (e.g., of a Monoclonal Antibody or a therapeutic protein) upon moving to a larger bioreactor indicates a failure to maintain the optimal production environment.

| Possible Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal oxygen transfer (kLa) [34] [2] | 1. Calculate and measure the kLa in the large-scale vessel.2. Compare dissolved oxygen profiles with lab-scale data. | Re-calibrate agitation and sparging rates to achieve the target kLa (e.g., 80 hr⁻¹ for a MAb process) [34]. |

| Nutrient gradients [34] [35] | 1. Use CFD modeling to simulate mixing patterns.2. Measure metabolite (e.g., glucose, lactate) levels at different locations. | Adapt impeller design (e.g., from radial to axial) to improve mixing homogeneity [34]. |

| Inadequate DoE model [34] [21] | Review the experimental ranges and factors included in your original DoE. Were key scale-dependent parameters like P/V included? | Conduct a new scale-down DoE study focusing on parameters that change with scale. Use the model to re-optimize conditions. |

Experimental Protocol: DoE for Scalable MAb Production Objective: To optimize cell culture conditions for maximum titer in a scaled-up bioreactor. Methodology:

- Define Factors and Ranges: Select critical process parameters (CPPs) such as pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and media composition. Define a relevant range for each (e.g., pH 6.8-7.2) based on prior knowledge [34].

- Generate DoE Matrix: Use software (e.g., MODDE, JMP) to create a D-optimal design that efficiently covers the multi-factor space with a manageable number of experiments [21].

- Execute Experiments: Run the experiments in a controlled, small-scale (e.g., 2L) bioreactor system.

- Build Predictive Model: Statistically analyze the results to generate a model that predicts titer based on the CPPs.

- Scale-Up Optimization: Use the model to identify the optimal setpoint for the CPPs. Apply these conditions to the large-scale (e.g., 200L) bioreactor [34].

Issue: Poor Cell Growth and Viability in a Scaled-Up Bioreactor

This issue is common with shear-sensitive cells, such as those used in cell and gene therapies, including human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs).

| Possible Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| High shear stress [2] [21] | 1. Monitor cell morphology and aggregate size distribution.2. Check for an increase in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), indicating cell damage. | Evaluate media additives like Pluronic F68 or Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) to protect cells from shear [21]. Reduce agitation speed if possible. |

| Inconsistent aggregate stability (for 3D cultures) [21] | 1. Image aggregates daily and measure size distribution.2. Corregate size with pluripotency marker expression (e.g., OCT4). | Use a DoE to optimize media additives (e.g., Heparin, PEG) that control aggregate fusion and stability, allowing for lower, less damaging agitation speeds [21]. |

| Inhomogeneous culture environment [35] | Sample from different parts of the bioreactor to check for gradients in pH, nutrients, or waste products. | Improve mixing strategy; consider different impeller designs or the use of single-use bioreactors with optimized mixing profiles. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing hiPSC Aggregate Stability Using DoE Objective: To control hiPSC aggregate size and maintain pluripotency in a suspension bioreactor. Methodology:

- Select Additives: Choose factors known to affect aggregate stability, such as Heparin, Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), and Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) [21].

- Design Experiment: Use software to create a D-optimal interaction design with a center point. The design should include multiple runs (e.g., 16 conditions plus 3 center points) to efficiently model interactions [21].

- Run Bioreactor Assays: Seed hiPSCs in multiple small-scale (e.g., 100 ml) vertical wheel bioreactors with the different media formulations.

- Measure Responses: Daily, sample and measure key response variables:

- Aggregate Size: Using brightfield imaging and image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

- Cell Growth: Count dissociated cells to calculate doubling time.

- Pluripotency Maintenance: Use flow cytometry to assess markers like OCT4 and SOX2.

- Generate and Use Models: Build separate mathematical models for each response (growth, pluripotency, stability). Use a desirability function to find the formulation that best satisfies all criteria simultaneously [21].

Issue: Inconsistent Product Quality (e.g., Glycosylation Patterns) Across Scales

Maintaining critical quality attributes (CQAs) is non-negotiable for regulatory approval and therapeutic efficacy.

| Possible Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Process parameter shifts [34] | Track CQAs (titer, purity, glycosylation) at every scale from 50L to 1000L. Use statistical regression to find parameters correlating with shifts. | Conduct extensive validation studies to ensure parameter setpoints (e.g., for pH and dissolved O₂) that control CQAs are maintained across all scales [34]. |

| Uncontrolled process variation [38] | Implement SPC charts (e.g., Individual-X and Moving Range charts) for key CQAs during development runs. | Use SPC rules to detect special cause variation early. Investigate and eliminate root causes (e.g., raw material lot change) before the process moves out of control [38]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments for bioprocess optimization.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Bioprocess Optimization |

|---|---|

| Pluronic F68 [21] | A surfactant that protects cells from shear stress in agitated bioreactor cultures by reducing surface tension. |

| Heparin Sodium Salt (HS) [21] | Enhances aggregate stability and can prevent unwanted fusion of cell aggregates (e.g., in hiPSC cultures). |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [21] | Used to control aggregate fusion and improve the stability of cells in suspension culture. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) [21] | A synthetic polymer used as a cell-protective agent and to promote stable aggregate formation. |

| Essential 8 (E8) Medium [21] | A defined, xeno-free cell culture medium formulation optimized for the growth and maintenance of human pluripotent stem cells. |

Key Parameter Relationships for Scale-Up

Understanding how different parameters interrelate is crucial for successful scale-up. The diagram below illustrates these logical relationships and how they are managed.

The table below consolidates key quantitative results from real-case studies, providing benchmarks for your scale-up projects.

| Process / Cell Type | Scale | Key Parameter Optimized | Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibody Production | 2L to 200L | Cell culture conditions via DoE | Achieved consistent yield of 1.8 g/L | [34] |

| Monoclonal Antibody Production | 20L to 500L | Oxygen transfer rate (kLa) | Achieved target kLa of 80 hr⁻¹ for optimal viability | [34] |

| hiPSC Expansion | 100mL Bioreactor | Media additives via DoE | Reduced doubling time by 40% vs. E8 medium alone | [21] |

| E. coli Fermentation | 1L to 100L | Constant Power per Volume (P/V) | Matched growth profiles (OD~600~ ~140) across scales | [36] |

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to support researchers in the scale-up of advanced bioprocesses. The content is framed within a broader thesis on bioreactor scale-up optimization, addressing common operational challenges in fed-batch and perfusion systems to enhance productivity and process robustness.

Troubleshooting Guides for Advanced Process Modes

Fed-Batch Process Troubleshooting

Problem: Inconsistent Cell Growth and Productivity in High-Density Fed-Batch Cultures

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Decline in growth rate and viability after initial batch phase [39] | Nutrient depletion (e.g., glucose, amino acids) | Implement or optimize a feeding strategy based on measured metabolite levels or predictive algorithms [39] [40]. |

| Accumulation of inhibitory metabolites (lactate, ammonia) [39] | Overflow metabolism due to excess substrate or inefficient metabolic pathways | Adjust feed composition and rate to avoid bolus feeding; consider controlled exponential feeding to match metabolic demand [39] [41]. |

| Drop in dissolved oxygen (DO) despite control cascades [39] [8] | Oxygen transfer rate (OTR) unable to meet demand of high cell density | Increase stirrer speed, gas flow, or oxygen partial pressure; optimize impeller design and sparger type during scale-up to maintain kLa [39] [8]. |

| Drop in pH and rise in lactate [42] | Buildup of acidic metabolites from feeding | Review and adjust base addition and CO2 control; fine-tune feed to shift cell metabolism [42]. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing an Intensified Fed-Batch Process via N-1 Seed Train Modification

Objective: To achieve a high inoculation density (e.g., 3–6 × 10^6 cells/mL) in the production bioreactor to shorten the culture duration and improve titer, without using perfusion equipment at the N-1 step [41].

- N-1 Bioreactor Setup: Inoculate the N-1 seed bioreactor using a conventional seed train.

- Intensification Strategy: Choose one of the following non-perfusion methods for the N-1 step:

- Production Bioreactor Inoculation: Harvest the intensified N-1 culture and use it to inoculate the production (N-stage) bioreactor at the high target VCD.

- Process Monitoring: Continue with the standard production fed-batch process, monitoring VCD, viability, titer, and product quality attributes. Compare performance against a control process using conventional inoculation density [41].

Perfusion Process Troubleshooting

Problem: Challenges in Maintaining Long-Term Perfusion Culture Stability

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Decline in cell viability or rapid changes in cell density [39] [43] | Inadequate nutrient supply or excessive waste product accumulation. | Optimize the Cell-Specific Perfusion Rate (CSPR). Calculate CSPR (pL/cell/day) and ensure it meets the specific requirements of your cell line and medium [43]. |

| Fouling or clogging of the cell retention device (e.g., ATF filter) [43] | Cell clumping or high cell density leading to filter blockage. | Implement a periodic cell bleed to control the total cell mass and reduce pressure on the filter. Optimize filter pore size and cleaning cycles [43]. |

| Genetic drift or loss of productivity over extended culture duration (weeks to months) [39] | Selective pressure on the cell population over many generations. | Ensure the stability of the production cell line is suitable for long-term culture. Monitor critical quality attributes (CQAs) regularly throughout the run [39]. |

| Inconsistent product quality or titer in the harvest [43] | Failure to reach a "pseudo-steady state" due to improper perfusion control. | Tightly control perfusion rates based on real-time or offline VCD measurements. Use a turbidostat approach or fixed perfusion rates validated to maintain stable metabolism [39] [43]. |

Experimental Protocol: Transferring a Fed-Batch Process to a Semi-Perfusion Mode

Objective: To establish a semi-perfusion process in a controlled, small-scale bioreactor for high productivity, based on an existing fed-batch platform [43].

- Preliminary Shake Flask Studies:

- Inoculate cells at ~2.5 × 10^6 cells/mL in shake flasks.