The Extracellular Matrix in 3D Cell Culture: From Silent Scaffold to Active Director of Cell Behavior

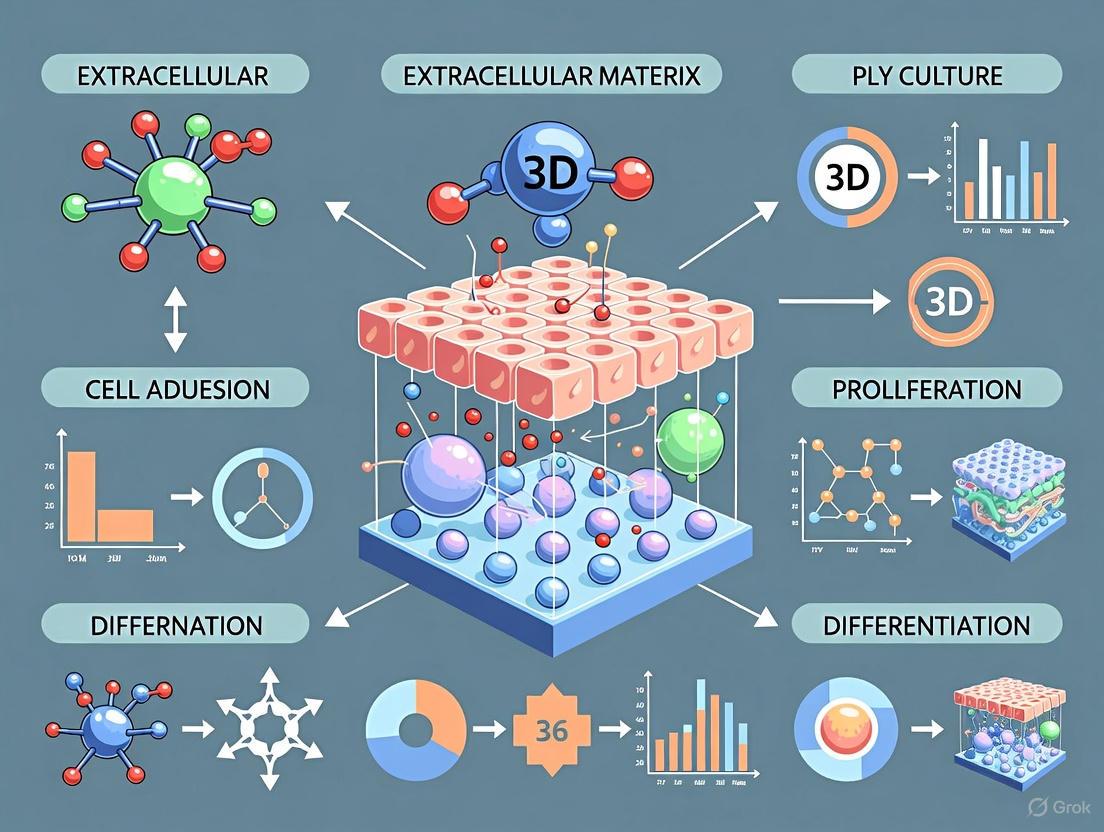

This article explores the pivotal role of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in advancing three-dimensional (3D) cell culture technologies for biomedical research and drug discovery.

The Extracellular Matrix in 3D Cell Culture: From Silent Scaffold to Active Director of Cell Behavior

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in advancing three-dimensional (3D) cell culture technologies for biomedical research and drug discovery. It covers the foundational biology of the ECM, detailing its composition and critical functions in providing structural, biochemical, and mechanical cues that direct cell fate. The review compares leading methodological approaches for creating ECM-mimicking environments, including decellularized scaffolds, hydrogels, and organoids, highlighting their applications in developing more physiologically relevant disease models. It further addresses key technical challenges and optimization strategies for these 3D systems. Finally, the article examines the compelling evidence that validates ECM-rich 3D models as superior tools for predicting drug efficacy and toxicity, ultimately discussing their transformative potential in personalized medicine and reducing reliance on animal models.

Beyond a Scaffold: Deconstructing the Multifunctional Role of the Native ECM

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is far more than a passive, structural scaffold for cells; it is a dynamic and biologically active 3D network of macromolecules that orchestrates critical aspects of cellular behavior, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival. In the context of three-dimensional (3D) cell culture research, recapitulating the complex properties of the native ECM is paramount for creating physiologically relevant in vitro models. The shift from traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayers to 3D culture systems is fundamentally centered on providing cells with an environment that mimics the in vivo ECM, thereby yielding more predictive data for drug discovery, cancer research, and regenerative medicine [1] [2]. This technical guide delves into the core composition of the ECM, its pivotal role in 3D cell culture, and the advanced methodologies used to model its complexity for biomedical research.

Core Composition and Biochemical Properties of the ECM

The ECM is a complex meshwork composed of hundreds of distinct molecules, which can be broadly categorized into a few key classes. Its specific biochemical and biophysical composition varies between tissues and is dynamically remodeled during developmental and disease processes.

Key Macromolecular Components

The primary functional components of the ECM include:

- Collagens: The most abundant proteins in the ECM, providing tensile strength and structural integrity. Collagen IV is a major component of the basement membrane [3].

- Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and Proteoglycans: Polysaccharide chains that attract water and ions, forming a hydrated gel that confers resistance to compressive forces and serves as a reservoir for growth factors [3].

- Glycoproteins: Multi-adhesive proteins that facilitate cell-ECM adhesion. Key examples include:

- Laminin: A major component of the basement membrane that influences cell differentiation, migration, and adhesion.

- Fibronectin: Connects cells to collagen fibers and is crucial for cell migration and wound healing.

- Vimentin: While traditionally considered an intracellular filament protein, its significant overexpression in tumor-derived ECM highlights the unique compositional shifts in disease states [3].

Table 1: Key Macromolecular Components of the Extracellular Matrix

| Component Class | Key Examples | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrous Proteins | Collagen I, IV; Elastin | Structural integrity, tensile strength, and elasticity. |

| Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) | Hyaluronic Acid, Chondroitin Sulfate | Hydration, compressive resistance, growth factor binding. |

| Glycoproteins | Laminin, Fibronectin, Vimentin | Cell adhesion, signaling, migration, and tissue organization. |

Quantitative Differences in Normal vs. Tumor ECM

The critical role of the ECM is starkly evident when comparing normal and pathological tissues. Research using Patient-Derived Scaffolds (PDS) has quantified significant alterations in tumor ECM composition and mechanics, which actively drive cancer progression.

Table 2: Quantitative Differences Between Normal and Tumor-Derived ECM (PDS)

| ECM Parameter | Normal PDS | Tumor PDS | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen Content | 226.71 µg/mg | 469.59 µg/mg | Increased stiffness and structural remodeling in tumors [3]. |

| GAG Content | 1.90 µg/mg | 2.99 µg/mg | Altered chemical signaling and hydration [3]. |

| Young's Modulus (Stiffness) | Significantly lower | Significantly higher | Creates a mechanobiological environment conducive to invasion [3]. |

| Key Protein Expression | Low expression of Collagen IV, Vimentin | Significant overexpression | Promotes an aggressive, invasive phenotype in cancer cells [3]. |

The Role of ECM in 3D Cell Culture Systems

In 3D cell culture, the ECM is the central element that defines the cellular microenvironment. It overcomes the limitations of 2D cultures by restoring cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions in all dimensions, leading to more authentic tissue-like structures and cellular responses [2].

Key Functions of ECM in 3D Models

- Mechanotransduction: The ECM transmits mechanical signals to cells via integrins and other adhesion receptors, influencing gene expression and cell fate. The increased stiffness of tumor PDS is a prime example of how ECM mechanics can promote invasive gene expression [3].

- Biochemical Signaling: The ECM serves as a reservoir for growth factors and cytokines, presenting them to cells in a spatially and temporally controlled manner. It also contains cryptic peptide sequences that are exposed upon proteolytic remodeling to influence cell behavior.

- Architectural Support: The 3D topography of the ECM guides tissue organization, polarity, and morphogenesis, which are essential for forming complex structures like spheroids and organoids [1] [2].

Experimental Modeling of the ECM in 3D Research

A variety of sophisticated experimental platforms have been developed to model the ECM for 3D cell culture, each with distinct advantages and applications.

Scaffold-Based Modeling Platforms

Scaffold-based systems provide a physical 3D structure that mimics the native ECM, supporting cell growth and organization.

- Natural Matrices:

- Corning Matrigel: A solubilized basement membrane preparation extracted from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse tumor, rich in laminin, collagen IV, and growth factors. It is widely used for organoid culture and studying cell invasion [2] [4]. A key limitation is batch-to-batch variability [2].

- Fibrin and Collagen Scaffolds: Natural polymers frequently used in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications [1] [5].

- Synthetic and Plant-Based Scaffolds:

- Hydrogels: Tunable networks of synthetic or natural polymers (e.g., PEG-based, alginate, PeptiGels) that offer high control over stiffness, porosity, and biochemical functionality [1] [2]. Edible plant-based scaffolds are an emerging, sustainable alternative [1].

- Patient-Derived Scaffolds (PDS): Decellularized human tissues that provide the most authentic, patient-specific ECM architecture and composition for research [3].

Detailed Protocol: Establishing 3D Cultures using Patient-Derived Scaffolds (PDS)

The following methodology outlines the process for creating a highly physiologically relevant 3D culture system using decellularized human tissue [3].

Objective: To decellularize human breast tissue and utilize the resulting ECM-based PDS as a platform for 3D culture of breast cancer cells to study tumor-specific ECM effects.

Materials and Reagents:

- Tissue Samples: Surgically resected breast tumor and adjacent normal breast tissue.

- Decellularization Solution: SDS-based buffer.

- Cell Culture Reagents: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cell culture media, antibiotics.

- Cell Line: MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

- Assay Kits: MTT cell viability assay, ELISA for IL-6, reagents for DNA/RNA quantification.

- Staining Solutions: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), DAPI, Trichrome, Sirius Red, Alcian Blue.

Procedure:

Tissue Decellularization:

- Subject normal and tumor tissue specimens to an SDS-based decellularization protocol.

- Validate complete cell removal via H&E and DAPI staining and DNA quantification (DNA content should be drastically reduced, e.g., from 527.1 ng/µL to 7.9 ng/µL) [3].

- Confirm preservation of key ECM components through biochemical assays (e.g., for collagen and GAG content) and histological staining (e.g., Trichrome for collagen, Alcian Blue for GAGs) [3].

Scaffold Characterization:

- Perform Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to verify ECM microstructure preservation and increased porosity post-decellularization.

- Conduct immunohistochemistry (IHC) for specific ECM proteins (e.g., Collagen IV, Vimentin) to confirm their overexpression in tumor PDS versus normal PDS.

- Perform a tensile test to measure the Young's modulus and confirm significantly higher stiffness in tumor PDS [3].

3D Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed MCF-7 breast cancer cells onto the pre-hydrated normal and tumor PDS.

- Maintain cultures in standard conditions, refreshing media as needed, for up to 15 days.

Functional Analysis:

- Cell Viability/Proliferation: Perform MTT assay on day 7 and day 15. Quantify cell nuclei directly by analyzing DAPI-stained images of the scaffolds [3].

- Gene Expression Analysis: On day 15, extract RNA from cells cultured on PDS. Use qRT-PCR to analyze the expression of hub genes associated with invasiveness (e.g., CAV1, CXCR4, CNN3, MYB, TGFB1), which are significantly upregulated in cells on tumor PDS [3].

- Cytokine Secretion: Collect conditioned media on day 15 and use an ELISA to quantify the secretion of IL-6, a cytokine correlated with tumor progression [3].

Diagram Title: 3D PDS Culture Workflow

Signaling Pathways and Downstream Functional Effects

The tumor-specific ECM induces aggressive cancer cell behavior by activating specific gene networks and signaling pathways. Bioinformatic analysis of invasive breast cancer cell lines has identified a co-expression network of hub genes associated with cell motility and migration [3].

Diagram Title: ECM-Driven Invasive Signaling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Working with ECM in 3D cell culture requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials and their functions in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ECM-Based 3D Cell Culture

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in 3D Cell Culture |

|---|---|

| Corning Matrigel Matrix | A natural basement membrane matrix used for cultivating organoids and studying cell invasion, providing a biologically active ECM environment [2] [4]. |

| Hydrogels (Synthetic & Natural) | Tunable polymers (e.g., PeptiGels, alginate) that create a defined 3D microenvironment with controllable stiffness and porosity for tailored experiments [1] [2]. |

| Patient-Derived Scaffolds (PDS) | Decellularized human tissues that provide a native, patient-specific ECM scaffold for highly physiologically relevant disease modeling and drug testing [3]. |

| Scaffold-Free Plates (e.g., ULA, Spheroid Microplates) | Low-attachment or micro-patterned plates that promote the self-aggregation of cells into scaffold-free 3D models like spheroids [1] [4]. |

| Microfluidic Chips (Organ-on-a-Chip) | Devices that co-culture cells with ECM in perfusable channels, allowing for the precise control of the microenvironment and the creation of dynamic tissue barriers [1] [6]. |

Research Applications and Future Directions

The ability to accurately model the ECM in vitro is transforming biomedical research, with significant implications for drug development and personalized medicine.

Key Application Areas

- Cancer Research: This is the largest application segment, accounting for approximately 34% of 3D cell culture use [1]. 3D models incorporating tumor-like ECM are pivotal for studying tumor invasion, drug resistance, and for developing personalized oncology approaches using patient-derived organoids (PDOs) [1] [3] [4].

- Drug Discovery and Toxicity Testing: 3D models with relevant ECM can replicate human tissue responses more accurately, reducing clinical trial failures and saving an estimated 25% in R&D costs for pharmaceutical companies [1]. Organ-on-a-chip technologies are particularly promising for predictive toxicity testing [1].

- Regenerative Medicine: 3D cultures are critical for organoid development and tissue engineering, aiming to create functional tissues for transplantation to address the global organ shortage [1].

Emerging Technological Integration

The field is rapidly advancing with the integration of cutting-edge technologies:

- 3D Bioprinting: Enables the precise spatial deposition of cells and "bioinks" (ECM-like hydrogels) to create complex, multicellular tissue constructs for drug testing and potential transplantation [1].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning: AI is used to analyze the complex, high-content data generated from 3D cultures (e.g., imaging, omics data), optimizing culture conditions, enhancing reproducibility, and identifying novel disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets [1] [6].

The extracellular matrix is the foundational element that defines the physiological context of cellular life. A deep understanding of its complex 3D network of macromolecules is no longer a niche interest but a prerequisite for advancing modern biomedical science. By employing the sophisticated experimental models and reagents detailed in this guide—from tunable hydrogels and patient-derived scaffolds to organ-on-a-chip systems—researchers can effectively mimic the in vivo ECM. This capability is crucial for bridging the translational gap between traditional 2D cultures, animal models, and human clinical outcomes, ultimately accelerating the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is not merely a structural scaffold but a dynamic, bioactive environment that critically regulates cell behavior in three-dimensional (3D) contexts. This whitepaper details the core biochemical components of the ECM—collagens, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins—focusing on their structure, function, and interplay within 3D cell culture systems. Understanding these components is essential for advancing research in tissue engineering, disease modeling, and drug development, as they directly influence cellular phenotypes, mechanotransduction, and tissue-specific responses in a way that traditional two-dimensional (2D) cultures cannot replicate.

In vivo, cells reside within a complex 3D network of extracellular matrix (ECM) that provides not only physical support but also critical biochemical and mechanical cues that direct cell fate. The shift from 2D to 3D cell culture models is driven by the recognition that cells in a 3D microenvironment exhibit more physiologically relevant behaviors, including differentiation, proliferation, migration, and drug responses [7] [8]. The ECM's core biochemical components—collagens, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins—orchestrate these cellular processes by forming a composite material with unique structural and signaling properties.

The ECM exhibits complex mechanical properties such as stiffness, nonlinear elasticity, viscoelasticity, and plasticity, all of which are sensed by cells through mechanotransduction pathways [7]. In 3D, mechanical confinement by the surrounding ECM restricts changes in cell volume and shape but allows cells to generate force on the matrix through actomyosin-based contractility and protrusions [7]. Furthermore, cell–matrix interactions are dynamic owing to constant matrix remodelling. This review will explore the fundamental roles of the core ECM components in creating a native-like 3D environment for cells.

Core Biochemical Components of the ECM

Collagens

Structure and Types

Collagens constitute the most abundant protein family in the human ECM and are the primary building blocks of connective tissues. The defining feature of collagen is a unique triple-helical structure formed by three polypeptide chains (α-chains). These chains are rich in proline and glycine and assemble into a right-handed triple helix, providing exceptional tensile strength [9]. At least 28 types of collagen have been identified, with Type I collagen being the most ubiquitous, forming large, banded fibrils that provide structural integrity to tissues like skin, tendon, and bone [7] [9]. Type IV collagen, in contrast, forms a flexible, sheet-like network that is a foundational element of the basement membrane [7].

Function in 3D Microenvironments

In 3D cell culture, collagen hydrogels are widely used as scaffolds due to their excellent biocompatibility and ability to promote cell adhesion, migration, and tissue-specific organization [9] [10]. Cells bind to collagen primarily through integrin receptors (e.g., α2β1, α1β1), triggering intracellular signaling pathways that regulate survival, proliferation, and differentiation [7]. The mechanical properties of collagen networks, such as their stiffness and degradability, play a critical role in regulating cell behavior in 3D. For instance, collagen networks exhibit strain-stiffening (nonlinear elasticity), where their resistance to deformation increases with applied strain [7].

Table 1: Key Collagen Types in the ECM and Their Functions in 3D Culture

| Collagen Type | Structural Form | Primary Tissue Distribution | Role in 3D Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Fibrillar | Skin, tendon, bone, ligaments | Most common scaffold material; promotes cell adhesion and migration; provides structural integrity [7] [9]. |

| Type II | Fibrillar | Cartilage, vitreous body | Supports chondrogenic phenotype; maintains cartilage-specific ECM [7]. |

| Type III | Fibrillar | Skin, blood vessels, reticular fibers | Often co-distributed with Type I; contributes to ECM compliance [10]. |

| Type IV | Network-forming | Basement membrane | Provides structural support for epithelial and endothelial cells; key for polarised tissue organization [7]. |

Proteoglycans and Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs)

Structure and Classification

Proteoglycans (PGs) are a diverse family of molecules consisting of a core protein to which one or more glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains are covalently attached [11] [12]. GAGs are long, unbranched polysaccharides made of repeating disaccharide units. Based on their localization, PGs are classified into several families:

- Intracellular PGs: (e.g., serglycin) [12].

- Cell-surface PGs: (e.g., syndecans, glypicans) [11] [12].

- Extracellular/Pericellular PGs: This group includes large, aggregating PGs like aggrecan in cartilage, and small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) such as decorin and biglycan, which interact with collagen fibrils [7] [12].

The major GAG types include heparan sulfate (HS), chondroitin sulfate (CS), dermatan sulfate (DS), keratan sulfate (KS), and the non-sulfated hyaluronic acid (HA) [12]. The sulfation patterns of GAG chains are critical for their ability to interact with a wide range of ligands [11].

Function in 3D Microenvironments

PGs and GAGs are multifunctional components that significantly influence the 3D cellular microenvironment through:

- Water Retention and Hydration: GAGs are highly negatively charged and hydrophilic, forming hydrated gels that resist compressive forces. This is particularly important in cartilage, where aggrecan and HA create a swellable, shock-absorbing matrix [7] [11].

- Molecular Reservoirs and Co-receptor Activity: HS chains on PGs like perlecan and syndecans bind and sequester a vast array of growth factors (e.g., FGFs, VEGF), chemokines, and morphogens. This creates concentration gradients and presents these signaling molecules to their respective cell-surface receptors, modulating key developmental and homeostatic pathways [12].

- Cell Adhesion and Migration: PGs on the cell surface and in the ECM facilitate or inhibit cell adhesion and migration. For example, the endothelial glycocalyx, a PG-rich layer on blood vessels, regulates leucocyte recruitment during inflammation [11].

- Regulation of Fibrillogenesis: SLRPs like decorin and lumican bind to collagen fibrils, regulating their diameter, organization, and overall ECM architecture [12].

Table 2: Major Proteoglycans and Their Functions in the ECM

| Proteoglycan | GAG Type | Localization | Core Function in 3D Microenvironment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggrecan | CS/KS | Extracellular (cartilage) | Forms large aggregates with HA; provides compressive resistance by hydrating the matrix [7] [12]. |

| Decorin | CS/DS | Extracellular | Binds to collagen I fibrils, regulating fibril assembly; binds TGF-β, modulating its activity [12]. |

| Versican | CS | Extracellular/Pericellular | Regulates cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation; involved in inflammation and cancer [12]. |

| Perlecan | HS | Basement Membrane | Key structural component of basement membrane; binds and stores growth factors (e.g., FGF) [12]. |

| Syndecan-1 | HS/CS | Cell Surface | Acts as a co-receptor for growth factors and integrins; influences cell-matrix adhesion and branching morphogenesis [11] [12]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | None (GAG only) | Extracellular | A non-sulfated GAG not attached to a protein core; interacts with CD44 and RHAMM receptors; regulates cell proliferation, migration, and mechanotransduction [7] [11]. |

Glycoproteins

Structure and Key Examples

Glycoproteins are proteins adorned with carbohydrate chains (oligosaccharides) that are typically smaller and more branched than GAGs. They play crucial roles in cell adhesion, migration, and ECM assembly. Key structural glycoproteins in the ECM include:

- Fibronectin: A large, dimeric glycoprotein that exists in soluble (plasma) and insoluble (cellular) forms. It contains multiple binding domains for other ECM components (e.g., collagen, fibrin) and for cell-surface integrins via its RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) sequence [13].

- Laminin: A large, cross-shaped trimeric glycoprotein that is a major constituent of the basement membrane. It self-assembles into a network and binds to other ECM components like type IV collagen and to cell-surface receptors such as integrins and dystroglycan, forming a stable adhesive substrate for epithelial and endothelial cells [7] [13].

- Elastin: The core component of elastic fibers, which provide tissues like blood vessels, skin, and lungs with the ability to recoil after transient stretch. Its precursor, tropoelastin, is cross-linked into a durable, stable network.

Function in 3D Microenvironments

Glycoproteins are master organizers of the ECM and are vital for creating a functional 3D niche:

- Nucleation of ECM Assembly: Fibronectin fibrillogenesis is often an early, essential step in the assembly of other ECM components, including collagen I and III. Cells use integrins to pull on fibronectin, unfolding it and exposing cryptic binding sites that promote its assembly into fibrils and the incorporation of other molecules [13].

- Cell Adhesion and Signaling: Glycoproteins like fibronectin and laminin are primary adhesion molecules for cells. Binding to their integrin receptors initiates intracellular signaling cascades (e.g., FAK, Src) that control cell cycle progression, survival, and cytoskeletal organization [8] [13].

- Providing Tensibility: Elastic fibers, composed of an elastin core and a microfibrillar sheath (containing fibrillin etc.), allow tissues to stretch and recoil, which is crucial for dynamic tissues.

Table 3: Principal Glycoproteins and Their Roles in 3D Culture Systems

| Glycoprotein | Molecular Structure | Primary Function | Role in 3D Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibronectin | Dimeric glycoprotein with RGD domain | Cell adhesion, migration, ECM assembly | Promotes initial cell attachment and spreading; nucleates collagen deposition and assembly [13]. |

| Laminin | Cross-shaped heterotrimeric glycoprotein | Basement membrane assembly; cell polarization | Supports epithelial and endothelial cell organization into polarised structures (e.g., acini, tubules) [7] [13]. |

| Elastin | Cross-linked hydrophobic polymer | Confers elasticity and recoil to tissues | Critical for engineering mechanically dynamic tissues like blood vessels and skin [8]. |

| Fibrillin | Glycoprotein forming microfibrils | Scaffold for elastin assembly; regulates TGF-β bioavailability | Provides structural framework for elastic fiber formation; mutations lead to Marfan syndrome. |

Advanced 3D Culture Models and Methodologies

Reconstituted ECM Scaffolds

A common approach to 3D culture involves using reconstituted ECM proteins to form hydrogels. Reconstituted Type I Collagen gels are a gold standard for many applications. The typical protocol involves mixing a chilled, acidic solution of collagen I with a neutralization buffer and cell suspension, then incubating at 37°C to trigger fibrillogenesis and gelation [7] [14]. Reconstituted Basement Membrane (rBM) matrices (e.g., Matrigel), derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma, are a heterogeneous mixture of laminin, type IV collagen, entactin, and PGs, and are ideal for culturing epithelial cells and forming organoids [7].

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a 3D Fibroblast-Collagen Culture for ECM Deposition Analysis [14] [13]

- Scaffold Preparation: Use a solution of acid-extracted bovine or rat tail Type I collagen. Neutralize the cold collagen solution on ice with an appropriate buffer (e.g., 10× PBS) and NaOH to achieve a physiological pH (pink color of phenol red indicator).

- Cell Encapsulation: Resuspend human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) in the neutralized collagen solution at a density of 0.5–25 × 10^6 cells/mL [15]. Pipette the cell-collagen mixture into culture wells.

- Gelation: Transfer the culture plate to a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 30–60 minutes to allow polymerization into a solid gel.

- Culture Maintenance: Overlay the gel with complete cell culture medium. Refresh the medium every 48–72 hours. Culture can be maintained for several weeks to study long-term ECM remodeling.

- Analysis:

- Decellularization: To analyze cell-deposited ECM, remove cellular material using extraction buffer (1% Tween-20 and 20 mM NH4OH in PBS) [13].

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Fix and stain the scaffold for deposited ECM proteins (e.g., fibronectin, collagen I, laminin) using specific primary and fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies [13].

- Multimodal Imaging: Analyze fixed samples using confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy (CLSFM) for protein localization, second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy for collagen fibril structure, and mass spectrometry imaging for molecular composition [14].

Synthetic and Biofunctionalized Scaffolds

To overcome batch-to-batch variability and immunogenicity of animal-derived materials, synthetic scaffolds and human-derived ECM are being developed. Electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds provide a synthetic 3D fibrous network that mimics the native collagen architecture. These scaffolds can be coated with ECM proteins to enhance cell attachment and bioactivity [13]. Human ECM-like collagen (hCol) derived from cultured mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) is an emerging alternative. hCol exhibits a hierarchical structure and proper post-translational modifications similar to native collagen, showing excellent bioactivity for tissue engineering applications [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for 3D ECM Research

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in 3D Culture |

|---|---|

| Type I Collagen (Bovine/Rat tail) | Forms the foundational hydrogel scaffold for a wide range of 3D culture models; supports fibroblast and stromal cell growth [7] [14]. |

| Reconstituted Basement Membrane (rBM) | Used for organoid generation and epithelial cell culture; provides a complex mixture of basement membrane proteins [7]. |

| Fibronectin | Coating agent or additive to promote cell adhesion and migration within scaffolds; crucial for initial ECM assembly [13]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Used in hydrogel formulations to mimic soft tissue environments (e.g., brain, cartilage); influences cell proliferation and mechanosensing [7] [8]. |

| Transforming Growth Factor-β1 (TGF-β1) | Cytokine used to stimulate fibroblast activation and ECM deposition (e.g., collagen, fibronectin); models fibrotic disease or CAF phenotype [13]. |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) Inhibitors | Used to study the role of ECM degradation and remodeling in cell invasion and migration [7]. |

| PrestoBlue HS / Resazurin | Cell viability assay reagent used to monitor metabolic activity of cells proliferating in 3D microbioreactors over time [15]. |

| Decellularization Buffer (Tween-20/NH4OH) | Removes cellular material from 3D cultures to isolate and analyze the cell-secreted ECM [13]. |

Signaling Pathways and Cellular Crosstalk in 3D

The core ECM components do not function in isolation but integrate to activate key signaling pathways that dictate cell behavior in a 3D context. The following diagrams illustrate two critical pathways mediated by these components.

Diagram 1: Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. Cells sense collagen matrix stiffness and density via integrin receptors, triggering actomyosin contractility and translocation of YAP/TAZ into the nucleus to drive transcription [7].

Diagram 2: Proteoglycan-mediated growth factor signaling. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the ECM bind and concentrate growth factors, presenting them to their cognate receptors on the cell surface to potentiate signaling [11] [12].

The core biochemical components of the ECM—collagens, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins—work in concert to create a sophisticated 3D microenvironment that is fundamental to in vivo-like cell behavior. Collagens provide structural integrity and mechanical cues, proteoglycans regulate hydration, growth factor signaling, and resilience, while glycoproteins orchestrate cell adhesion and ECM assembly. A deep and integrated understanding of these components, their interactions, and their roles in signaling is indispensable for the design of physiologically relevant 3D cell culture models. The continued development of advanced scaffolds, including human-derived ECM and biofunctionalized synthetic materials, coupled with multimodal analytical techniques, will further enhance our ability to model human tissues accurately, thereby accelerating drug discovery and regenerative medicine.

The Extracellular Matrix (ECM) is a dynamic, three-dimensional network that provides far more than just structural scaffolding for tissues and organs. It serves as a sophisticated signaling hub that actively regulates fundamental cellular processes including proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival through its intricate control of growth factor bioavailability [16] [17]. The ECM achieves this regulatory function primarily through the sequestration of growth factors within its structure, creating localized reservoirs that are protected from degradation and can be released in a spatially and temporally controlled manner in response to specific physiological cues [16]. This mechanism is crucial for maintaining tissue homeostasis and orchestrating complex biological processes such as development, wound healing, and regeneration.

In the context of 3D cell culture research, understanding these ECM-growth factor dynamics is particularly critical. The native 3D microenvironment presents a more physiologically relevant context for studying cell behavior compared to traditional 2D cultures, as it better recapitulates the complex cell-ECM interactions that occur in vivo [7]. The ECM's role as a growth factor reservoir significantly influences cellular responses in 3D environments, affecting experimental outcomes and their translational relevance for drug development and tissue engineering applications.

Molecular Mechanisms of Growth Factor Sequestestration

ECM Components as Binding Reservoirs

The ECM sequesters growth factors through specific molecular interactions with its various structural components. Key among these are proteoglycans, which possess glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains that electrostatically interact with growth factors.

Table 1: Major ECM Components Involved in Growth Factor Sequestration

| ECM Component | Structure | Example Growth Factors Bound | Binding Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs) | Protein core with heparan sulfate GAG chains | FGF2, HGF, VEGF, TGF-β | Electrostatic interactions between negatively charged sulfate groups on GAG chains and basic amino acids in growth factors [17] |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Linear polysaccharide, non-sulfated GAG | TGF-β, BMPs | Forms framework that binds proteoglycans; indirect sequestration via proteoglycan networks [17] |

| Fibrillin | Glycoprotein, forms microfibrils | TGF-β, BMPs | Latent TGF-β binding proteins (LTBPs) tether latent complexes to fibrillin in ECM [7] |

| Type IV Collagen | Network-forming collagen, basement membranes | VEGF, FGF2 | Heparin-binding domains in growth factors interact with collagen-associated HSPGs [7] |

The sequestration mechanism serves multiple biological functions: it stabilizes growth factors against proteolytic degradation, creates local concentration gradients that guide cellular responses, and prevents premature receptor activation until appropriate physiological signals trigger release [17]. For example, HS proteoglycans can facilitate fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling by immobilizing them via their heparin-binding domains [17].

Regulatory Dynamics of Sequestration and Release

The ECM environment dynamically regulates the equilibrium between growth factor sequestration and release through several integrated mechanisms:

Enzymatic Remodeling: Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other proteases cleave ECM components to release bound growth factors. This process is counterbalanced by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), which maintain homeostasis [17].

Mechanical Force Application: Cellular traction forces can expose cryptic binding sites in ECM proteins like fibronectin, altering growth factor binding affinity and availability [17].

Receptor Availability Modulation: Recent research reveals that cholesterol-rich membrane domains such as caveolae can sequester growth factor receptors (e.g., TGFβR and EGFR), preventing their activation even when growth factors are present. This adds another layer of regulation to ECM-growth factor signaling [18].

Diagram 1: Growth Factor Sequestration and Release from ECM. The diagram illustrates how growth factors are sequestered in the ECM reservoir through proteoglycan binding and latent complex formation, and released via proteolytic cleavage, mechanical force, or cholesterol modulation. A critical activation barrier involves receptor sequestration in cholesterol-rich caveolae, which can be disrupted by cholesterol modulation to enable signaling.

Experimental Approaches in 3D Culture Systems

Recapitulating ECM-Growth Factor Dynamics

Advanced 3D culture models have been developed to better mimic the physiological ECM environment and study growth factor dynamics. These include:

Patient-Derived Scaffolds (PDS): Created through decellularization of human tissues, PDS preserve native ECM architecture and composition. A 2025 study decellularized human breast tissues using an SDS-based protocol that effectively removed cellular components while preserving key ECM constituents including collagen and glycosaminoglycans [3]. The resulting scaffolds maintained structural integrity and biochemical complexity, allowing researchers to demonstrate that tumor-specific ECM characteristics promote cancer cell proliferation and aggressive behavior compared to normal ECM [3].

Biomimetic Hydrogel Systems: Engineered scaffolds incorporating ECM components enable controlled study of growth factor presentation. A 2025 wound healing study developed gelatin-based hydrogels that incorporated growth factors (EGF, PDGF, VEGF) with cyclodextrins to modulate receptor accessibility [18]. These hydrogels demonstrated sustained release kinetics rather than burst release, providing more physiological growth factor delivery profiles that significantly improved healing outcomes in diabetic mouse models [18].

Methodologies for Studying Sequestered Growth Factors

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Analyzing ECM-Growth Factor Interactions

| Method | Protocol Overview | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Decellularization | 1. Tissue dissection into thin sections2. SDS-based detergent treatment with agitation3. DNase/RNase enzymatic treatment4. Sterilization and storage in PBS | Preservation of native ECM architecture and endogenous growth factors; creation of physiological 3D culture environments [3] | Confirm complete DNA removal (<50 ng/mg tissue); verify retention of key ECM components (collagen, GAGs) through biochemical assays [3] |

| ECM Component Quantification | 1. Tissue digestion with proteinase K2. GAG content: dimethylmethylene blue assay3. Collagen content: hydroxyproline assay4. Sulfated GAGs: alcian blue staining | Comparative analysis of ECM composition between normal and pathological states; correlation of ECM changes with cellular behaviors [3] | Include standard curves for accurate quantification; use complementary methods (histology, biochemical assays) for validation |

| Growth Factor Release Profiling | 1. Incorporation into hydrogel systems2. ELISA-based quantification of released factors3. Assessment of bioactivity via cell-based assays4. Modulation with cholesterol-disrupting agents (e.g., MβCD) | Evaluation of release kinetics; testing therapeutic efficacy of sustained delivery systems; investigating receptor accessibility [18] | Use physiological buffers; monitor stability of released factors; include relevant biological endpoints (migration, proliferation) |

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation in Disease States

Disruption of normal ECM-growth factor dynamics contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis. In chronic wounds, elevated cholesterol synthesis leads to sequestration of growth factor receptors within lipid rafts, impairing their signaling capacity despite adequate growth factor presence [18]. This pathological mechanism was demonstrated through spatial analysis of human chronic wound biopsies, which revealed altered distributions of cholesterol and other lipid species compared to acute wounds [18].

In cancer progression, tumor-associated ECM remodeling creates a microenvironment that promotes aggressive behavior. Research using patient-derived scaffolds showed that breast cancer cells cultured on tumor-derived ECM significantly upregulated invasive genes (CAV1, CXCR4, CNN3, MYB, TGFB1) and secreted higher levels of IL-6 compared to those cultured on normal ECM [3]. This suggests that tumor-specific ECM alterations actively drive malignant progression rather than merely accompanying it.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting ECM-Growth Factor Interactions

Emerging therapeutic approaches aim to restore normal ECM-growth factor dynamics:

Cholesterol Modulation: Cyclodextrins (MβCD, HβCD) extract cholesterol from cellular membranes, disrupting caveolae and releasing sequestered growth factor receptors. In diabetic wound models, this approach restored growth factor responsiveness and significantly accelerated healing [18].

ECM-Targeted Delivery Systems: Nanotechnology-based strategies and biomaterial scaffolds enable localized delivery of growth factors with controlled release kinetics, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects [16].

Enzymatic ECM Remodeling: Targeted approaches to normalize pathological ECM composition and structure are being explored to restore physiological growth factor signaling in conditions like fibrosis and cancer [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying ECM-Growth Factor Dynamics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decellularization Agents | Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), Triton X-100, DNase/RNase enzymes | Creation of patient-derived scaffolds (PDS) | Removal of cellular material while preserving native ECM structure and composition [3] |

| ECM Component Assays | Dimethylmethylene blue (GAGs), hydroxyproline assay (collagen), alcian blue staining | Quantitative and qualitative ECM analysis | Measurement of specific ECM components to characterize scaffold composition and integrity [3] |

| Cholesterol Modulators | Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HβCD) | Restoring growth factor receptor accessibility | Extraction of cholesterol from membrane lipid rafts to release sequestered growth factor receptors [18] |

| Biomaterial Scaffolds | Gelatin-based hydrogels, decellularized ECM scaffolds, synthetic polymer matrices | 3D cell culture and therapeutic delivery platforms | Providing physiological context for cell growth; enabling controlled release of bioactive factors [18] [19] |

| Protease Inhibitors | TIMP proteins, broad-spectrum protease inhibitors | Studying ECM turnover and growth factor release | Inhibition of endogenous proteases to stabilize ECM-bound factors and analyze baseline conditions [17] |

The recognition of the ECM as a dynamic signaling hub rather than a passive scaffold has fundamentally transformed our understanding of tissue regulation and cellular behavior. The controlled sequestration and regulated release of growth factors represents a crucial mechanism for spatial and temporal control of signaling in physiological and pathological processes. For researchers utilizing 3D culture systems, faithfully recapitulating these ECM dynamics is essential for generating biologically relevant data and predictive models.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing increasingly sophisticated ECM-mimetic platforms that dynamically respond to environmental cues, integrating multiple cell types to better model the complexities of tissue microenvironments, and advancing therapeutic strategies that target specific aspects of ECM-growth factor interactions for conditions ranging from chronic wounds to cancer [16] [17]. As these technologies evolve, they will continue to enhance our ability to study and manipulate the fundamental processes that govern tissue homeostasis and disease.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for ECM-Growth Factor Research. The diagram outlines a systematic approach to studying ECM-growth factor dynamics, beginning with comprehensive ECM analysis, progressing through appropriate 3D model selection, testing targeted interventions, and concluding with multifaceted outcome assessment.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a dynamic, three-dimensional network that provides far more than just structural support to tissues; it is a rich source of biochemical and mechanical cues that fundamentally govern cellular behavior [16]. Its mechanical properties, particularly stiffness—the resistance of a material to deformation—serve as a critical regulator of cell fate, influencing processes ranging from differentiation and proliferation to migration and apoptosis [16]. The process by which cells sense and respond to these mechanical cues, known as mechanotransduction, is therefore pivotal to understanding development, homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis. This whitepaper delves into the molecular mechanisms of stiffness-directed cell fate, framed within the advancing context of 3D cell culture research, which offers more physiologically relevant environments than traditional 2D models [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this mechanical dialogue is key to developing novel therapeutic strategies for conditions like cancer, fibrosis, and regenerative medicine [20] [16].

Fundamental Concepts: ECM Composition and Stiffness

The ECM's composition is a complex interplay of macromolecules, including collagens (providing tensile strength), elastin (conferring resilience), fibronectin (crucial for cell adhesion), and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) (maintaining structural hydration and facilitating signaling) [16]. The specific composition and architectural organization of these components determine the matrix's mechanical properties.

Stiffness, often quantified as the Young's modulus (E), varies significantly across tissues and pathological states, providing a mechanical context that cells constantly monitor. The following table summarizes typical stiffness values for various biological contexts.

Table 1: ECM Stiffness Across Tissues and Pathological States

| Tissue or Condition | Approximate Stiffness | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|

| Brain (Soft Tissue) | < 2 kPa | Represents a soft, compliant microenvironment [16]. |

| Healthy Breast Tissue | ~0.17 kPa | Baseline soft tissue stiffness [16]. |

| Breast Cancer Tumor | ~4.0 kPa | Significant stiffening compared to healthy tissue [16]. |

| Fibrotic Lung | ~16.5 kPa | 5-10 times stiffer than healthy lung tissue [16]. |

| Bone (Hard Tissue) | 40-55 MPa | Represents a rigid, load-bearing environment [16]. |

Cells perceive these stiffness gradients through a process called durotaxis, where they actively migrate toward stiffer regions [16]. This sensing is not passive; cells probe their environment by exerting contractile forces through actin-myosin cytoskeleton and integrin-based adhesions, gauging the resistance the matrix offers [21].

Molecular Mechanisms of Mechanosensing and Transduction

The cellular response to ECM stiffness is orchestrated through an integrated network of mechanosensors and signaling pathways that convert external physical forces into biochemical signals.

Key Mechanosensors and Signaling Hubs

The mechanotransduction process involves a series of molecular players working in concert:

- Integrins: Transmembrane receptors that bind to ECM ligands externally and link to the actin cytoskeleton internally, forming focal adhesions. These structures are primary sites for force transmission [20] [16] [21].

- Piezo1 Channels: Mechanosensitive ion channels that open in response to membrane tension, allowing Ca²⁺ influx, which acts as a rapid second messenger. For instance, in Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), Piezo1 activation triggers calcium influx and subsequent mTOR signaling, selectively enhancing IL-13 protein production [22].

- YAP/TAZ Pathway: Transcriptional co-activators that are pivotal downstream effectors of mechanotransduction. In a soft ECM, YAP/TAZ are sequestered in the cytoplasm and degraded. On a stiff ECM, mechanical forces from the cytoskeleton promote their nuclear translocation, where they partner with transcription factors like TEAD to drive expression of genes promoting proliferation and stemness [20] [16].

The interplay between these components is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: Core mechanotransduction signaling from ECM stiffness. The diagram illustrates how stiff ECM promotes integrin-mediated force transmission, leading to YAP/TAZ nuclear localization and gene activation, and how Piezo1 channel activation triggers calcium-mTOR signaling to regulate protein translation.

The Nuclear Connection

Mechanical signals are not limited to the cytoplasm. Forces are transmitted from the cytoskeleton to the nucleus via the LINC complex, influencing nuclear architecture and gene expression [20]. This can lead to changes in chromatin organization and direct mechanical regulation of transcription. During events like cell migration across stiff matrix interfaces, this force transmission can cause nuclear deformation and even DNA damage, further influencing cell phenotype [21].

Quantitative Data: ECM Stiffness Directs Specific Cell Fates

The impact of ECM stiffness on cell lineage specification is demonstrated by quantitative experimental data across multiple cell types. The following table consolidates key findings from recent research.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence of Stiffness-Directed Cell Fate

| Cell Type | ECM Stiffness | Cell Fate / Response | Key Readouts & Quantitative Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Cells [16] | 1 kPa (Soft) vs. 12 kPa (Stiff) | Proliferation | Stiffness (12 kPa) activated AKT and STAT3 pathways, promoting tumor proliferation. |

| Breast Cancer Cells (MCF-7) [3] | Tumor vs. Normal PDS | Aggressive Phenotype | Tumor PDS (stiffer) induced ~4x higher IL-6 secretion (122.91 vs. 30.23 pg/10⁶ cells) and upregulated invasiveness genes (CAV1, CXCR4, TGFB1). |

| Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC2s) [22] | Mechanical stress via Piezo1 | IL-13 Production | Piezo1 activation (e.g., by agonist Yoda1) selectively enhanced IL-13 protein production via Ca²⁺-mTOR axis, without affecting IL-5. |

| Invasive Breast Cancer Cells (MDA-MB-231) [21] | Dense vs. Open Collagen I Matrix | Phenotype Switching & Migration | Cells transmigrating from dense to open matrix showed increased contractility, directed migration, and misregulated nuclear mechanotransduction (YAP, emerin). |

Experimental Approaches in 3D Culture Models

Moving beyond 2D cultures is critical for replicating the in vivo mechanical microenvironment. Several advanced 3D models are now employed.

Patient-Derived Scaffolds (PDS)

This innovative technique utilizes decellularized human tissue to create a biologically and mechanically relevant ECM scaffold for cell culture [3].

- Protocol Workflow:

- Tissue Acquisition: Surgically resected breast tumor and normal healthy breast tissues are obtained.

- Decellularization: Tissues are treated with an SDS-based protocol to remove all cellular components while preserving key ECM components (collagen, GAGs). Validation includes H&E and DAPI staining showing no nuclei, and DNA quantification confirming significant reduction (e.g., from 527.1 ng/μL to 7.9 ng/μL) [3].

- Characterization: Histological staining (Trichrome, Sirius Red) and biochemical assays confirm preservation and abundance of ECM components. Tensile testing confirms higher stiffness in tumor PDS versus normal PDS [3].

- 3D Cell Culture: Cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7) are seeded onto the PDS and cultured. Outcomes like cell viability (MTT assay), proliferation (DAPI count), gene expression (qPCR), and cytokine secretion (ELISA) are analyzed to assess the impact of tumor-specific ECM [3].

The workflow and key outcomes of this approach are visualized below.

Diagram 2: Patient-derived scaffold workflow for 3D culture. The process involves decellularizing human tissue to create a native ECM scaffold, which is characterized and used for 3D cell culture, enabling analysis of cell behavior in a realistic microenvironment.

Engineered Collagen I Interface Model

To study metastasis, a defined matrix interface model mimicking the boundary between dense tumor tissue and softer healthy tissue has been developed [21].

- Protocol Workflow:

- Surface Coating: Glass coverslips are coated with poly(styrene-alt-maleic anhydride) (PSMA) for covalent attachment of collagen.

- Sequential Polymerization: Two collagen type I solutions of different concentrations (creating different pore sizes and densities) are polymerized sequentially on the coverslip to create a sharp, defined interface.

- Cell Embedding and Analysis: Invasive breast cancer cells (e.g., MDA-MB-231) are embedded in the dense compartment.

- Live-Cell Imaging and PIV: Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) is used to quantify collagen network deformation and cellular traction forces during transmigration.

- Immunostaining: Cells are fixed and stained for mechanotransduction markers (e.g., YAP localization, emerin) to correlate forces with signaling outcomes [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential reagents and materials used in the featured experiments for studying ECM stiffness and mechanotransduction.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Mechanotransduction Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen I | Major structural ECM protein for constructing 3D matrices; concentration controls pore size and stiffness. | Engineered interface models for studying cell transmigration [21]. |

| Piezo1 Agonist (Yoda1) | Selective chemical activator of the Piezo1 channel, used to probe its function. | Studying Piezo1-mediated calcium influx and its effect on ILC2 cytokine production [22]. |

| Piezo1 Inhibitor (GsMTx4) | Selective peptide inhibitor of Piezo1, used to block mechanosensitive channel activity. | Validating the role of Piezo1 in Yoda1-induced IL-13 upregulation [22]. |

| Patient-Derived Scaffolds (PDS) | Decellularized human tissue providing a native, patient-specific ECM microenvironment. | Culturing MCF-7 cells to study the effect of tumor-specific ECM on cancer cell aggression [3]. |

| YAP/TAZ Antibodies | Immunostaining to determine the subcellular localization (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic) of YAP/TAZ. | Assessing mechanotransduction pathway activation in cells on stiff vs. soft substrates or after transmigration [21]. |

| mTOR Inhibitors | Pharmacological blockers (e.g., rapamycin) of the mTOR pathway, a key downstream signaling node. | Confirming the role of mTOR in Piezo1-mediated translational control of cytokine production [22]. |

The evidence is unequivocal: ECM stiffness is a master regulator of cell lineage and fate, operating through conserved mechanotransduction pathways like integrin signaling, Piezo1, and YAP/TAZ. The adoption of physiologically relevant 3D models, such as Patient-Derived Scaffolds and engineered matrix interfaces, is providing unprecedented insights into how mechanical cues drive both normal physiology and disease progression, particularly in cancer and fibrosis [6] [3] [21].

For the field of drug discovery, this mechanistic understanding opens up a new frontier for therapeutic intervention: mechanomedicine [20]. Future efforts will focus on developing small molecules, biologics, and nanomedicines that target key nodes in the mechanotransduction network—such as Piezo1, ROCK, or YAP/TAZ-TEAD interaction—to normalize aberrant mechanical signaling [20] [22] [16]. Furthermore, the integration of 3D bioprinting and AI-driven analysis with these advanced culture platforms promises to enhance the scalability and predictive power of mechanobiology research, accelerating the development of next-generation diagnostics and targeted therapies [6]. By continuing to decode the mechanical language of the ECM, researchers and clinicians can look forward to a future where manipulating the tissue microenvironment becomes a central pillar of precision medicine.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) undergoes profound remodeling in pathological conditions, transitioning from a regulator of tissue homeostasis to a driver of disease progression in cancer and fibrosis. This whitepaper examines the parallel mechanisms underlying ECM dysregulation in these conditions, highlighting the critical roles of increased stiffness, altered composition, and aberrant cell-ECM signaling. Through comprehensive analysis of current research models and emerging therapeutic strategies, we demonstrate how targeting the pathological ECM offers promising avenues for intervention. The content is framed within the context of 3D cell culture research, which provides essential platforms for replicating the complex biomechanical and biochemical properties of diseased tissues, thereby enabling more accurate drug screening and mechanistic studies.

The extracellular matrix constitutes a dynamic, complex network of proteins, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans that provides structural support and biochemical cues essential for tissue development, homeostasis, and repair. The ECM is broadly classified into basement membrane (BM) and interstitial matrix (IM), each with distinct compositional and functional characteristics [23] [24]. The BM, composed primarily of collagen IV and laminin, forms a specialized sheet-like structure that surrounds epithelial, endothelial, and muscle cells, providing structural support and establishing cell polarity [23]. The IM, consisting mainly of fibrillar collagens (types I, III, V), fibronectin, and elastin, confers mechanical strength and elasticity to tissues [24]. In healthy tissues, the ECM undergoes continuous, tightly regulated remodeling that maintains tensional homeostasis through balanced synthesis and degradation [25].

Pathological ECM remodeling represents a fundamental hallmark of both cancer and fibrotic diseases, characterized by excessive deposition, altered organization, and post-translational modifications of ECM components [23] [24] [25]. This remodeling creates a self-perpetuating cycle where matrix stiffness and composition drive disease progression through mechanotransduction pathways. In cancer, the tumor microenvironment (TME) becomes characterized by a fibrotic stroma that promotes malignancy through enhanced tumor cell growth, survival, migration, and treatment resistance [23] [25]. Similarly, in fibrotic diseases affecting organs such as the lung, liver, and pancreas, aberrant ECM accumulation leads to tissue scarring, loss of function, and eventual organ failure [24] [26]. The concept of "mechanoreciprocity" describes how cells tune their cytoskeletal tension in response to ECM stiffness, subsequently remodeling their ECM to reach a new tensional equilibrium that typically favors disease progression [23].

Hallmarks of Pathological ECM Remodeling

Increased Stiffness and Cross-Linking

The pathological ECM is characterized by significantly increased stiffness primarily resulting from excessive deposition of fibrillar collagens and enhanced enzymatic cross-linking [23] [25]. This process is driven primarily by activated fibroblasts and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) that secrete abundant ECM proteins while simultaneously upregulating cross-linking enzymes such as lysyl oxidases (LOX) and transglutaminases [23] [24]. Collagen cross-linking occurs through a multi-step process initiated by lysyl hydroxylases (LHs) that catalyze lysine hydroxylation, followed by LOX-mediated oxidative deamination that generates reactive aldehydes forming covalent cross-links between collagen fibrils [23]. In tumors such as breast and lung cancers, upregulation of LH2 shifts collagen cross-links from lysine aldol-derived (LCCs) to hydroxylysine aldol-derived (HLCCs), resulting in a stiffer, more organized matrix that correlates with tumor aggression and reduced patient survival [23].

The biomechanical properties of the pathological ECM exhibit non-linear elasticity and viscoelastic behavior, meaning that stiffness increases with applied strain (strain-stiffening) and exhibits both solid and liquid characteristics [23]. This enables cellular contractions to significantly increase stiffness sensed by neighboring cells hundreds of microns away, facilitating long-range mechanical communication within the tissue [23]. In pulmonary fibrosis, healthy lung tissue stiffness typically ranges between 1-5 kPa, while fibrotic tissue exceeds 10 kPa, creating a mechanically aberrant environment that perpetuates disease progression [26].

Altered Composition and Architecture

Pathological remodeling fundamentally alters ECM composition and organization. In cancer, the normally isotropic collagen organization becomes anisotropically aligned, creating tracks that facilitate cancer cell migration and invasion [23]. This aligned collagen signature (TACS3 in breast cancer) correlates with tumor aggression and reduced patient survival [23]. Similar alignment patterns are observed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), where highly aligned stromal collagen correlates with reduced post-surgical survival [23].

The quantitative alterations in ECM components between normal and pathological states are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of ECM Components in Normal vs. Pathological Conditions

| ECM Component | Normal Tissue | Pathological Tissue | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Collagen | 186.94 μg/mg (breast) [3] | 507.35 μg/mg (breast tumor) [3] | Increased stiffness, barrier function |

| Glycosaminoglycans | 1.62 μg/mg (breast) [3] | 3.07 μg/mg (breast tumor) [3] | Enhanced water retention, growth factor binding |

| Collagen Cross-linking | Low [23] | High (HLCC predominant) [23] | Increased tensile strength, resistance to degradation |

| Fibrillar Collagen Alignment | Isotropic [23] | Anisotropic (aligned) [23] | Creation of migration tracks for invasive cells |

| MMP Expression | Homeostatic levels [27] | Elevated (e.g., MMP-16) [27] | Enhanced ECM remodeling and invasion |

The compositional changes extend to specific ECM proteins. Tumor ECM shows significant overexpression of collagen IV, vimentin, and other structural components compared to normal ECM [3]. These alterations create a dense physical barrier that restricts drug delivery while simultaneously activating pro-fibrotic and pro-tumorigenic signaling pathways [28] [25].

Key Cellular Actors and Signaling Pathways

The development of pathological ECM is driven by activated mesenchymal cells, primarily myofibroblasts and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). These cells exhibit enhanced contractility, elevated expression of α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), and excessive production of ECM components [24]. Myofibroblast activation depends on a complex signaling network centered around the TGF-β superfamily, beginning with mechanical stress-induced release of TGF-β from its latent complex, followed by canonical SMAD signaling and transcriptional upregulation of genes encoding αSMA and ECM proteins [24].

Cells sense and respond to the mechanical properties of the pathological ECM through multiple receptor systems, including integrins, discoidin domain receptors (DDRs), and mechanosensitive ion channels such as PIEZO1 [29] [25]. DDR1-mediated collagen signaling in pancreatic cancer, for instance, exacerbates fibrotic barriers that impede macromolecular drug delivery through PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activation [28]. The relationship between ECM stiffness, cellular sensing, and downstream signaling creates a vicious cycle that drives disease progression, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Vicious Cycle of Pathological ECM Remodeling. ECM stiffness activates mechanotransduction pathways that promote myofibroblast/CAF differentiation, leading to further ECM production and disease progression in a self-reinforcing loop.

Experimental Models for Studying Pathological ECM

3D Cell Culture Systems

Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures fail to replicate the complex cell-ECM interactions present in vivo, limiting their utility for studying pathological ECM remodeling [30]. Consequently, research has shifted toward three-dimensional (3D) models that better recapitulate the dynamic cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions within native tissues [30]. These 3D systems preserve cellular physiology and molecular characteristics while enhancing translational relevance [26].

Spheroid models represent one approach for 3D culture, where cancer cells self-aggregate into spherical structures that mimic aspects of solid tumors. Studies comparing 2D versus 3D cultures of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells revealed notable phenotypic transitions supported by differential expression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers and matrix components, including altered expression of syndecans and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [30]. These models provide a matrix-free platform for studying intrinsic cellular aggregation properties but lack the physiological ECM context of native tissues.

Scaffold-based systems incorporate biological or synthetic matrices to provide both structural and biochemical cues. Patient-derived scaffolds (PDS) obtained through decellularization of surgically resected tissues preserve the native ECM architecture and composition, offering a highly physiological microenvironment for cell culture [3]. A detailed protocol for generating and utilizing PDS is provided in Section 3.3.

Synthetic hydrogel platforms offer precise control over mechanical and biochemical properties, enabling systematic investigation of specific ECM parameters. Poly(ethylene glycol) norbornene (PEG-NB) hydrogels, for instance, allow independent tuning of stiffness, degradation kinetics, and bioactive ligand presentation [26]. These systems have been used to model pulmonary fibrosis by replicating the stiffness of healthy (∼5 kPa) and fibrotic (∼19 kPa) lung tissue, demonstrating that combined mechanical and biochemical cues drive pathogenic cellular responses resembling in vivo fibrosis [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for ECM and Fibrosis Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Systems | PEG-NB [26], Matrigel [30], Collagen [26] | 3D cell culture | Provide tunable mechanical support and biochemical cues |

| Decellularization Agents | SDS [3] | Patient-derived scaffolds | Remove cellular content while preserving ECM structure |

| Pro-fibrotic Cocktail | TGF-β, TNF-α, IL-13 [26] | Disease modeling | Induce fibrotic phenotypes in vitro |

| MMP Substrates | MMP-degradable peptides (e.g., VPMS↓MRGG) [26] | Biomaterial design | Enable cell-mediated hydrogel remodeling |

| Adhesive Ligands | RGD (fibronectin mimic) [26], IGSR (laminin mimic) [26] | Mechanotransduction studies | Promote cell adhesion and signaling |

| Anti-fibrotic Drugs | Nintedanib [26] | Therapeutic screening | Inhibit fibroblast activation and ECM production |

| Mechanotransduction Modulators | DDR1/2 inhibitors [28], PIEZO1 activators [29] | Pathway analysis | Target specific mechanosensing pathways |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Patient-Derived Scaffolds for Cancer ECM Studies

The use of patient-derived scaffolds (PDS) represents a cutting-edge approach for modeling the tumor ECM in its native context. Below is a detailed methodology adapted from recent breast cancer research [3]:

1. Tissue Acquisition and Preparation

- Obtain surgically resected breast tumor and normal adjacent tissue specimens from biobanks or fresh surgical collections.

- Process tissues into uniform fragments (e.g., 5mm³ pieces) using sterile surgical tools.

- Wash thoroughly in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing antimicrobial agents (100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 10 μg/mL gentamycin sulfate, and 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B) to remove residual blood and contaminants.

2. Decellularization Protocol

- Incubate tissue fragments in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution with continuous agitation for 24-48 hours at room temperature.

- Replace SDS solution every 12 hours until tissue becomes opaque and translucent.

- Rinse extensively with deionized water to remove residual detergent (6-8 washes over 24 hours).

- Treat with DNase I (50 U/mL in PBS) for 6 hours at 37°C to remove residual DNA.

- Perform final rinses with PBS containing antimicrobial agents.

- Store decellularized scaffolds in PBS at 4°C for immediate use or freeze at -80°C for long-term storage.

3. Quality Control and Validation

- Confirm decellularization through H&E staining showing absence of nuclear material while maintaining ECM architecture.

- Quantify DNA content to verify reduction to <50 ng/mg of tissue (from >500 ng/mg in native tissue).

- Assess retention of ECM components through:

- Glycosaminoglycan quantification (e.g., Blyscan assay)

- Collagen content measurement (e.g., hydroxyproline assay)

- Histological staining (Trichrome, PAS, Sirius red, Alcian blue)

- Immunohistochemistry for specific ECM proteins (collagen IV, vimentin)

- Evaluate mechanical properties through tensile testing to determine Young's modulus.

4. 3D Cell Culture on PDS

- Seed appropriate cell lines (e.g., MCF-7 breast cancer cells at 5,000-15,000 cells per scaffold) onto sterilized PDS.

- Culture in complete medium (DMEM with 10% FBS) for up to 15 days, monitoring cell viability and proliferation regularly.

- Assess functional outcomes including:

- Gene expression of invasiveness markers (CAV1, CXCR4, CNN3, MYB, TGFB1) via qRT-PCR

- Cytokine secretion profiles (e.g., IL-6 ELISA)

- Cell morphology and distribution within scaffolds (histology, SEM)

The complete workflow for PDS generation and application is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Workflow for Patient-Derived Scaffold Generation and Application. Surgical specimens are decellularized, validated, and used as physiological substrates for 3D cell culture and disease modeling.

Therapeutic Targeting of Pathological ECM

Anti-Fibrotic Strategies

Targeting the pathological ECM represents a promising therapeutic approach for both fibrotic diseases and cancer. Nintedanib, an FDA-approved anti-fibrotic drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), has demonstrated efficacy in 3D human lung models by reducing fibroblast activation and promoting epithelial repair genes [26]. Treatment with Nintedanib downregulated key fibroblast activation markers (ACTA2, COL1A1) while upregulating transitional and alveolar type I cell markers, indicating potential restoration of epithelial repair mechanisms [26].

Emerging strategies focus on specific ECM assembly and remodeling pathways. Inhibition of collagen cross-linking through LOX or LOX-like family members can reduce tissue stiffness and decrease tumor aggression [23]. Similarly, targeting DDR1-mediated collagen signaling in pancreatic cancer enhances macromolecular drug delivery by diminishing collagen I expression in pancreatic stellate cells [28]. Isoform-specific targeting has shown that inhibiting DDR1, but not DDR2, effectively reverses fibrotic barriers through modulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, particularly alternative mTOR complexes involving MEAK7 and GIT1 [28].

Challenges in ECM-Targeted Therapies

Despite the promising potential of ECM-targeted therapies, several challenges remain. The complexity and heterogeneity of the ECM across tissues and disease states complicates the development of broadly effective treatments [25]. Additionally, the dense fibrotic ECM acts as a physical barrier to drug delivery, potentially limiting the efficacy of therapeutic agents [28] [25]. There is also risk of off-target effects, as ECM components play essential roles in normal tissue homeostasis and repair [25].

Successful clinical translation will require sophisticated approaches that consider disease stage, specific ECM alterations, and combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple aspects of disease pathogenesis. The development of biomarkers to stage fibrosis and monitor disease activity represents a critical component for patient stratification and treatment monitoring [24].

The pathological ECM represents more than a passive scaffold in fibrotic diseases and cancer—it actively drives disease progression through biomechanical and biochemical signaling. Understanding the parallel mechanisms underlying ECM remodeling in these conditions provides valuable insights for therapeutic development. The emergence of sophisticated 3D culture models, including patient-derived scaffolds and tunable hydrogel systems, has significantly advanced our ability to study these processes in physiologically relevant contexts.

Future research directions should focus on developing increasingly sophisticated human 3D models that better capture the cellular heterogeneity and dynamic remodeling of diseased tissues. Additionally, the discovery of novel biomarkers to stage ECM remodeling and monitor therapeutic response will be essential for clinical translation. As our understanding of the pathological ECM continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention that disrupt the vicious cycle of ECM-driven disease progression.

Engineering the Cellular Niche: Techniques for ECM-Mimetic 3D Culture

In the field of 3D cell culture research, the Extracellular Matrix (ECM) is far more than a passive scaffold; it is a dynamic, information-rich microenvironment that is fundamental to directing cell behavior, from differentiation and proliferation to tissue-specific function [31]. The transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) culture to three-dimensional (3D) models is driven by the need to better recapitulate the physiological environment, where cell-to-cell interactions and diffusion gradients create tissue-like conditions that are impossible to achieve on a flat plastic surface [32]. Within this context, Decellularized ECM (dECM) scaffolds have emerged as a premier platform technology. They are engineered by removing the cellular components from native tissues or organs while preserving the intricate 3D architecture and biochemical composition of the original ECM [33]. This process yields a non-immunogenic biological template that provides the critical mechanical support, biochemical cues, and tissue-specific context essential for advanced 3D cell culture models, regenerative therapies, and drug screening applications [34] [35].

Fabrication of dECM Scaffolds: Methodologies and Protocols

The core objective of decellularization is the complete removal of cellular material—a source of immunogenicity—while minimizing damage to the structural and functional integrity of the native ECM. The success of a protocol depends on factors such as tissue density, lipid content, and thickness [33].

Core Decellularization Techniques

Decellularization methods are typically classified into three categories, which are often used in combination [31] [36]:

- Physical Methods: These techniques disrupt cell membranes through physical forces. Freeze-thaw cycles are common, where the formation of intracellular ice crystals causes cell lysis. Other methods include immersion and agitation, and perfusion for whole organs [33].

- Chemical Methods: This involves the use of chemical agents to lyse cells and dissolve cytoplasmic components.

- Ionic Detergents: Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is highly effective at solubilizing lipid membranes and nuclear material but can disrupt ECM structure and reduce glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content [31] [37].

- Non-ionic Detergents: Triton X-100 disrupts lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions but is less effective for dense tissues [31].

- Acidic/Basic Solutions: Alkaline and acid solutions can degrade nucleic acids and disrupt cell membranes [31].

- Enzymatic Methods: Enzymes like nucleases (DNase, RNase) are used to digest residual genetic material after cell lysis. Trypsin is also used to dissociate cells [38].

The workflow below illustrates the general process for creating and applying a dECM scaffold.

Experimental Protocol: Cartilage Decellularization

A 2025 study provides a detailed protocol for creating a dECM bioink for cartilage tissue engineering [37].

- Tissue Source: Native cartilage tissue.

- Decellularization Protocol:

- Physical Decellularization: Subject the tissue to multiple freeze-thaw cycles. This involves immersion in liquid nitrogen followed by thawing in a water bath to disrupt chondrocytes.

- Chemical Decellularization: Treat the tissue with an adjusted concentration of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) to solubilize cell membranes and remove cellular debris while minimizing collagen damage.

- dECM Preparation: The decellularized cartilage matrix is then solubilized using a urea extraction method to obtain the dECM component for bioink formulation [37].

- Validation:

- Histology: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining confirmed the removal of chondrocytes, with only empty lacunae visible.

- Biochemical Assay: A Bradford assay demonstrated that approximately 59% of the protein content was preserved, indicating successful decellularization with substantial ECM retention [37].

Characterization of dECM Scaffolds: Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

Rigorous characterization is essential to confirm the efficacy of decellularization and the functional properties of the resulting dECM scaffold.

Biochemical and Structural Analysis

The following table summarizes key characterization methods and typical outcomes from recent research.

Table 1: Key Characterization Methods for dECM Scaffolds

| Analysis Type | Method | Purpose & Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Removal | Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) Staining | Visual confirmation of cell removal; presence of empty lacunae indicates success. | [37] |

| Protein Content | Bradford Assay | Quantifies total protein preservation post-decellularization. A study showed ~59% retention. | [37] |

| Rheology | Oscillatory Rheometry | Measures viscoelastic properties (Storage Modulus G', Loss Modulus G''). Essential for bioprintability. | [37] |