Viral Vector Structure-Function Studies: From Molecular Architecture to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of viral vector structure-function relationships, bridging fundamental virology with therapeutic development.

Viral Vector Structure-Function Studies: From Molecular Architecture to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of viral vector structure-function relationships, bridging fundamental virology with therapeutic development. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the structural basis of viral vector efficiency, methodologies for functional characterization, strategies for overcoming manufacturing and immunological challenges, and comparative validation of leading platforms including adenovirus, AAV, and lentivirus vectors. By integrating recent advances in vector engineering, manufacturing scale-up, and clinical safety data, this review serves as a strategic guide for optimizing viral vector design for gene therapy and vaccinology.

Decoding Viral Vector Architecture: Structural Components and Functional Mechanisms

Comparative Structural Biology of Major Viral Vector Platforms

Viral vectors are engineered viruses designed to deliver therapeutic genetic material into human cells, forming the cornerstone of modern gene therapy. The structural biology of these vectors—the precise architecture of their protein capsids, envelopes, and genomes—directly dictates their function, including which tissues they can target (tropism), how efficiently they deliver their genetic cargo (transduction efficiency), and how they are recognized by the immune system. Within the clinical and research landscape, adeno-associated viruses (AAV) and lentiviruses (LV) have emerged as two of the most prominent and successfully deployed viral vector platforms. [1] [2] This guide provides a comparative structural analysis of these key platforms, framing the discussion within the context of structure-function relationships that are critical for researchers and drug development professionals selecting the optimal vector for a given application.

The functional differences between AAV and lentiviral vectors are rooted in their distinct structural designs.

Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors

AAV is a small, non-enveloped virus with an icosahedral capsid approximately 260 Å in diameter. [3] The capsid is composed of 60 protein subunits arranged in a T=1 symmetry. These subunits are the viral proteins (VP) VP1, VP2, and VP3, which are produced in a ~1:1:10 ratio and share a common C-terminal region. [3] The VP3 common region forms the core of the capsid structure, featuring an eight-stranded β-barrel motif conserved across all AAV serotypes. [3] The diversity in tissue tropism and antigenic properties among serotypes arises from the sequence and conformation of the variable regions (VRs) on the surface loops inserted between the β-strands. [3]

The single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome of AAV is about 4.7 kb in length. [3] For recombinant AAV (rAAV) vectors, the viral rep and cap genes are replaced by the therapeutic expression cassette, which is flanked by the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). These ITRs are the only cis-acting elements required for genome replication and packaging. [2] A defining structural feature of the AAV capsid is the presence of a pore at the five-fold symmetry axis, which is postulated to serve as a portal for the externalization of the VP1-unique (VP1u) region during endosomal escape and for genome packaging. [3]

Lentiviral Vectors

Lentiviruses, a subclass of retroviruses, are enveloped viruses. The viral core, which contains the RNA genome and essential enzymes, is surrounded by a lipid bilayer derived from the host cell membrane. [4] This structural characteristic is a fundamental differentiator from non-enveloped AAV. The viral core is often described as conical or bullet-shaped. [4]

The RNA genome of lentiviruses is approximately 9-10 kb, with recombinant lentiviral vectors (rLV) capable of packaging up to 8-12 kb of foreign genetic material. [4] The vector genome is flanked by Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs) that are essential for reverse transcription and integration into the host genome. [4] A key structural component is the viral envelope, which is decorated with glycoproteins that determine the vector's tropism. In recombinant lentiviral vectors, the native envelope is often replaced with envelopes from other viruses, such as the vesicular stomatitis virus G-glycoprotein (VSV-G), to broaden the range of infectable cells (pseudotyping). [2]

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Characteristics of AAV and Lentiviral Vectors

| Structural Feature | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) |

|---|---|---|

| Virion Structure | Non-enveloped, icosahedral capsid [4] | Enveloped, spherical virion with a conical core [4] |

| Capsid/Envelope | Protein capsid composed of VP1, VP2, VP3 proteins [3] | Host cell-derived lipid bilayer with envelope glycoproteins [4] |

| Genome Type | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) [3] | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) [4] |

| Packaging Capacity | ~4.7 kb [4] | ~8-12 kb [4] |

| Key Genomic Elements | Inverted Terminal Repeats (ITRs) [3] | Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs) and packaging signal (ψ) [4] |

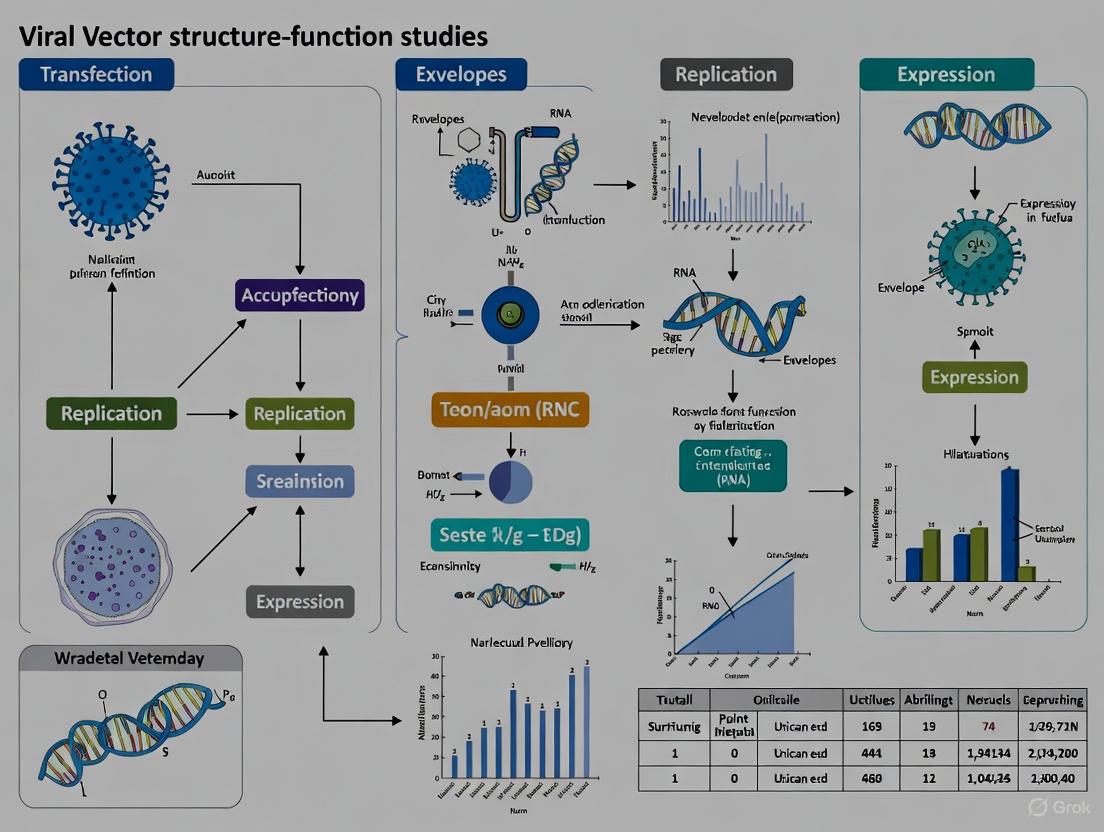

Diagram 1: Comparative structural models of AAV and Lentiviral vectors.

Structural Determinants of Function and Experimental Data

The structural differences between AAV and LV platforms lead directly to their distinct functional profiles in gene delivery applications.

Tissue Tropism and Cell Entry

AAV Tropism: AAV's tissue specificity is primarily determined by the surface topology of its capsid. The variable regions (VRs) on the capsid surface mediate the initial attachment to primary cell surface receptors (e.g., AAV2 uses heparan sulfate proteoglycan) and subsequent engagement with co-receptors for internalization. [3] This makes serotype selection or engineering of the capsid a critical factor for targeting specific tissues. [3] [2]

Lentiviral Tropism: LV tropism is largely defined by the glycoproteins embedded in its lipid envelope. [2] The ability to pseudotype LVs with different envelope proteins (e.g., VSV-G) allows researchers to alter and broaden their cellular tropism flexibly, making them versatile tools for infecting a wide range of dividing and non-dividing cells. [2]

Genomic Fate and Transgene Expression

AAV Genomic Fate: The ssDNA genome of rAAV predominantly remains as non-integrated, episomal DNA in the nucleus of transduced cells. [4] [2] This leads to long-term transgene expression in non-dividing cells but dilution in rapidly dividing cell populations. This episomal persistence is generally associated with a lower risk of insertional mutagenesis. [2]

Lentiviral Genomic Fate: Following entry, the lentiviral RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into DNA and integrates into the host cell's genome. [4] This enables stable, long-term transgene expression in both dividing and non-dividing cells and their progeny, which is a critical advantage for ex vivo stem cell and T-cell therapies. However, this necessitates careful safety considerations regarding the site of integration. [2]

Table 2: Functional Comparison Based on Structural Biology

| Functional Property | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | In vivo gene delivery [2] | Ex vivo gene delivery (e.g., CAR-T, HSCs) [2] |

| Tropism Determinant | Protein capsid serotype / VRs [3] | Envelope glycoprotein (pseudotype) [2] |

| Genomic Integration | Largely non-integrating (episomal) [4] | Integrates into host genome [4] |

| Typical Onset | Slow (requires ssDNA to dsDNA conversion) | Rapid |

| Duration of Expression | Long-term in non-dividing cells [2] | Long-term (stable in dividing cells) [4] |

| Key Safety Consideration | Pre-existing immunity, empty capsids [5] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis [2] |

Supporting Experimental Data: AAV Serotype Comparison in Heart Tissue

To illustrate how structural differences translate to functional outcomes, consider a study that compared the gene transfer efficiency of different AAV serotypes in a mouse organotypic heart slice culture model. [6] This experimental system preserves the native 3D architecture of the myocardium, providing a robust platform for evaluating vector performance.

Experimental Protocol:

- Tissue Preparation: Left ventricular (LV) tissue slices (300 µm thick) were prepared from transgenic mice expressing mCherry in cardiomyocytes using a vibrating microtome. [6]

- Culture Conditions: Slices were cultured at an air-liquid interface and maintained under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. [6]

- Viral Transduction: Four recombinant AAV serotypes (1, 2, 6, 8), all expressing Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) under the CAG promoter, were applied to the slice surface. [6]

- Quantification: Gene transfer efficiency was quantified by counting the number of GFP-positive cells per slice. Cell tropism was determined by co-localization of GFP with the mCherry cardiomyocyte marker. [6]

Results: The study demonstrated that AAV6 exhibited the highest transduction efficiency, with GFP expression almost exclusively in cardiomyocytes. [6] In contrast, AAV1, 8, and especially AAV2 showed significantly lower numbers of GFP-positive cells. [6] This finding highlights the critical impact of capsid serotype (structure) on efficacy in a specific target tissue.

Table 3: Experimental Data from AAV Serotype Comparison in Heart Slices [6]

| AAV Serotype | Relative Gene Transfer Efficiency | Primary Cell Tropism in Heart |

|---|---|---|

| AAV1 | Moderate | Cardiomyocytes |

| AAV2 | Low | Mixed |

| AAV6 | Highest | Predominantly Cardiomyocytes |

| AAV8 | Moderate | Cardiomyocytes |

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for AAV serotype comparison in heart slices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful viral vector research and development relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Viral Vector Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Packaging Plasmids | Provide viral genes (cap/rep for AAV; gag/pol/rev for LV) in trans during vector production. | AAV: Rep/Cap plasmid; LV: 2nd or 3rd generation packaging systems. [4] |

| Transfer Plasmid | Carries the therapeutic gene expression cassette flanked by necessary ITRs (AAV) or LTRs (LV). | The design of this plasmid is specific to the viral vector platform. [4] |

| Helper Plasmid | Provides auxiliary viral functions needed for replication (e.g., adenovirus E4, E2A, VA for AAV). | Used in the AAV triple-transfection protocol. [4] |

| Producer Cell Line | Cell line used to produce the viral vectors via transfection. | HEK293 cells are widely used for both AAV and LV production. [5] |

| Transfection Reagent | Facilitates the introduction of packaging/transfer plasmids into producer cells. | Polyethylenimine (PEI) is commonly used. [5] |

| Purification Kits/Resins | For purifying and concentrating viral vectors from cell lysates or supernatants. | Chromatography resins; iodixanol gradients. |

| Titer Assay Kits | Quantify the physical or functional vector particles before use. | qPCR for genome titer; ELISA for capsid titer. |

| Cell Culture Media | Supports the growth of producer and target cells. | Serum-free suspension media are common for scalable production. [5] |

The choice between AAV and lentiviral vectors is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with the therapeutic goal, guided by a deep understanding of their structural biology. The AAV capsid is a masterclass in precision targeting, offering a palette of naturally occurring and engineered serotypes for efficient in vivo delivery to specific tissues, with a favorable safety profile rooted in its predominantly episomal genomic fate. In contrast, the lentiviral envelope and integrative machinery make it a powerful vehicle for stable genetic modification, particularly in ex vivo settings where permanent transgene expression in dividing cells is required, as in CAR-T therapies and stem cell engineering.

Future advancements in the field will continue to be driven by structural insights. Efforts are focused on engineering next-generation capsids and envelopes with enhanced tropism, reduced immunogenicity, and the ability to evade pre-existing neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, optimizing manufacturing processes, such as using high-throughput systems like AMBR 15 to improve AAV upstream production, is crucial for scalability and cost-effectiveness. [5] As the structural blueprints of these viral vectors are further decoded and refined, they will undoubtedly unlock new therapeutic possibilities and continue to reshape the landscape of gene therapy.

Viral vectors have emerged as indispensable tools in biomedical research and therapeutic development, with their efficacy and specificity fundamentally governed by their interaction with host cells. The initial entry of a virus into a target cell is a critical determinant of infection success and represents a key regulatory point for vector engineering. This process is mediated by the virus's outer structures—capsids for non-enveloped viruses and envelope proteins for enveloped viruses—which recognize specific cellular components to initiate infection [7] [8]. The concept of "viral tropism," or the specificity of a virus for particular cell types, tissues, or host species, is largely defined by these initial recognition and entry events [7] [8]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing these interactions provides the foundational knowledge required to engineer viral vectors with enhanced targeting capabilities, improved safety profiles, and higher transduction efficiency for gene therapy, vaccine development, and targeted cancer treatments [7] [9].

This guide systematically compares the structural and functional characteristics of capsid and envelope proteins across major viral vector classes, highlighting how these proteins determine tropism and mediate cell entry. By presenting quantitative data on receptor binding, entry pathways, and experimental approaches for tropism modification, we aim to provide researchers with a comprehensive resource for selecting and engineering viral vectors for specific applications. The integration of structural insights with functional outcomes will facilitate informed decision-making in viral vector development and application.

Structural Determinants of Viral Entry

Enveloped Viruses: Membrane Fusion Machinery

Enveloped viruses possess a lipid bilayer membrane derived from host cells, which surrounds the viral capsid and genome. Incorporated into this envelope are viral glycoproteins that mediate both attachment to host cells and the subsequent fusion of viral and cellular membranes [10] [11]. These envelope glycoproteins (EnvGPs) have evolved to perform two essential functions: receptor binding through specific domains that recognize cellular surface molecules, and membrane fusion through controlled conformational changes that ultimately lead to the delivery of the viral genetic material into the cytoplasm [10].

The fusion process follows a well-defined sequence of events that is largely conserved across different virus families, despite variations in the specific proteins involved. Following activation—either through receptor binding or the acidic pH of endosomes—EnvGPs undergo significant conformational changes that expose a previously hidden hydrophobic domain known as the fusion peptide [10]. This peptide inserts into the target cell membrane, destabilizing the lipid bilayer and initiating the fusion process. The subsequent refolding of the glycoprotein brings the viral and cellular membranes into close proximity, leading first to hemifusion (merger of the outer leaflets only) and culminating in the formation of a complete fusion pore through which the viral genome enters the cell [10].

Table 1: Classes of Viral Fusion Proteins and Their Characteristics

| Class | Structural Features | Representative Viruses | Fusion Trigger | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Trimeric hairpin structure with central α-helical coiled-coil | HIV, Influenza, Paramyxoviruses | Receptor binding (HIV) or low pH (Influenza) | Synthesized as inactive precursors requiring proteolytic cleavage; contains fusion peptide at N-terminus |

| Class II | Predominantly β-sheet structures with domain III rearrangement | Alphaviruses (SFV), Flaviviruses (Dengue, Zika) | Low pH in endosomes | Oriented parallel to viral membrane; fusion loops at the tip of the protein |

| Class III | Structural hybrid with both α-helical and β-sheet elements | Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV), Herpesviruses | Low pH or receptor binding | Combines features of both Class I and II fusion proteins |

Based on structural characteristics, viral fusion proteins are categorized into three distinct classes [12]. Class I fusion proteins, exemplified by influenza hemagglutinin (HA) and HIV Env, are characterized by a trimeric hairpin structure with a central α-helical coiled-coil and are typically synthesized as inactive precursors that require proteolytic cleavage for activation [8] [12]. Class II fusion proteins, found in alphaviruses like Semliki Forest Virus (SFV) and flaviviruses such as Dengue and Zika, feature predominantly β-sheet structures and undergo a domain III rearrangement during fusion [12]. Class III fusion proteins, represented by Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) G and Herpesvirus glycoproteins, incorporate structural elements from both Class I and II proteins [12].

The regulation of fusion activity is crucial for the viral life cycle, preventing premature activation before the virus encounters an appropriate target cell. This control is achieved through various mechanisms, including synthesis as inactive precursors requiring proteolytic cleavage by cellular proteases (such as furin), and maintaining the fusion machinery in a metastable state until activation by specific triggers like receptor binding or low pH [10].

Non-Enveloped Viruses: Capsid-Mediated Entry

Non-enveloped viruses lack a lipid envelope and instead rely on their proteinaceous capsid to protect the genetic material and mediate entry into host cells. The capsid must therefore contain the necessary molecular equipment for cell attachment, penetration, and ultimately delivery of the viral genome to the appropriate cellular compartment [11] [7]. Unlike enveloped viruses that fuse with cellular membranes, non-enveloped viruses must employ alternative strategies to cross the cellular membrane barrier, often involving capsid rearrangements or the formation of membrane pores [11].

The capsids of non-enveloped viruses are typically composed of repeating protein subunits arranged in highly symmetrical structures, most commonly icosahedral forms with triangulation numbers (T) of 3 or 4, consisting of 180 or 240 monomeric coat proteins, respectively [13]. These proteins self-assemble through non-covalent interactions including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic forces, and ionic interactions [13]. A key structural feature of many viral capsids is a highly electropositive surface created by clusters of basic amino acid residues, which facilitates interaction with the negatively charged viral RNA genome during packaging and may also participate in initial membrane interactions during entry [13].

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), among the most promising gene therapy vectors, exemplify the structural sophistication of non-enveloped viral capsids. AAV capsids are composed of three structural proteins—VP1, VP2, and VP3—that assemble into an icosahedral shell with a molar ratio of 1:1:10 [7]. These proteins not only protect the viral genome but also mediate the molecular interactions between ligands on the capsid surface and receptors on the target cell membrane, thereby determining viral tropism [7]. Different AAV serotypes, characterized by distinct capsid structures, have evolved to bind specific cellular receptors that vary across tissues, explaining their differing tropism profiles [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Entry Mechanisms Between Enveloped and Non-Enveloped Viruses

| Characteristic | Enveloped Viruses | Non-Enveloped Viruses |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Structure | Lipid bilayer with embedded glycoproteins | Proteinaceous capsid |

| Entry Mechanism | Membrane fusion | Pore formation, membrane disruption, or direct penetration |

| Genetic Material Delivery | Through fusion pore | Through capsid disassembly or formed channels |

| Primary Receptors | Cell surface proteins, glycans | Cell surface proteins, glycans, glycoproteins |

| Environmental Stability | Generally less stable, sensitive to desiccation, detergents, and solvents | Generally more stable, resistant to environmental stressors |

| Examples | HIV, Influenza, HSV, SARS-CoV-2 | AAV, Adenovirus, Poliovirus, Norovirus |

For non-enveloped viruses, the process of genome delivery often involves significant structural rearrangements of the capsid proteins triggered by specific cellular cues. These may include endosomal acidification, which induces conformational changes in capsid proteins, proteolytic processing by cellular proteases that systematically dismantle the capsid, or interactions with specific cellular factors that trigger controlled disassembly [14]. For example, polioviruses appear to generate pores in the endosomal membrane that allow viral RNA to exit without complete disassembly of the capsid, while adenoviruses employ a more disruptive entry strategy that involves partial disassembly and endosomal membrane disruption [11].

Molecular Mechanisms of Tropism Determination

Receptor Recognition and Binding

The initial attachment of a virus to a host cell is mediated by specific interactions between viral surface proteins and cellular receptors, which represent the primary determinant of viral tropism [8] [14]. These interactions are highly specific, with viruses evolving to recognize particular cell-surface molecules that serve as gateways to permissible host cells. The diversity of receptors targeted reflects the evolutionary adaptability of viruses and includes cell surface protein receptors (e.g., the CD4 receptor for HIV), glycans (e.g., sialic acid modifications for influenza), and various other molecular structures present on the surface of target cells [14].

The specificity of these receptor interactions directly explains the tissue and cell type preferences of different viruses. For instance, HIV's targeting of CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells through binding to the CD4 receptor and co-receptors CCR5 or CXCR4 underlies its tropism for immune cells and its role in immunodeficiency [7]. Similarly, the Rabies virus exhibits strong neuronal tropism due to its ability to bind specific neuronal receptors and undergo retrograde transport through the nervous system [7]. Even subtle differences in receptor structure can significantly impact tropism, as demonstrated by human and avian influenza viruses that preferentially recognize sialic acids with α2-6 and α2-3 linkages respectively, explaining their tropisms for human respiratory epithelia and avian intestinal tracts [8].

It is important to distinguish between authentic receptors that directly mediate viral entry and other cell surface molecules that may enhance infection indirectly. Authentic receptors not only facilitate virus attachment but also induce essential conformational changes in viral entry proteins that are prerequisites for membrane fusion or penetration [10]. In contrast, molecules such as heparan sulfate proteoglycans, DC-SIGN, or integrins often serve as attachment factors that concentrate viruses on the cell surface, enhancing infection efficiency without directly participating in the fusion process [10]. For example, DC-SIGN can bind to N-glycans on both influenza HA and HIV gp120, increasing viral concentration on the cell surface to facilitate subsequent interactions with authentic receptors [8].

Fusion Activation and Regulation

Following receptor binding, the activation of membrane fusion represents another critical control point in viral entry and a secondary determinant of tropism. Fusion activation mechanisms are broadly categorized as either pH-dependent or pH-independent, with significant implications for the cellular entry pathways utilized by different viruses [10] [11] [8].

pH-dependent viruses, such as influenza, alpha-, and rhabdoviruses, require endocytosis and exposure to the low pH environment of endosomes (typically pH 5.0-6.5) to trigger the conformational changes in their envelope proteins necessary for fusion [11] [8]. The acidification of endosomes protonates specific amino acid residues in the fusion proteins, modifying their interactions and triggering structural rearrangements that lead to membrane fusion [10]. This pH dependence means that these viruses predominantly enter cells through endocytic pathways and their infection can be inhibited by agents that raise the pH of acidic organelles, such as weak bases, ionophores, or specific inhibitors of vacuolar-type H+-ATPases like Bafilomycin A [11].

In contrast, pH-independent viruses, including coronaviruses, paramyxoviruses, and most retroviruses (like HIV), can fuse at the plasma membrane without requiring low pH activation [11]. For these viruses, fusion is triggered directly by interactions with specific receptors that induce the necessary conformational changes in the viral envelope proteins [8]. For instance, HIV envelope protein gp120 undergoes sequential conformational changes upon binding first to CD4 and then to co-receptors (CCR5 or CXCR4), ultimately triggering the fusion activity of gp41 [8]. Some viruses exhibit flexibility in their entry mechanisms, with certain strains of HIV capable of entering different cell types via either plasma membrane fusion or endocytic pathways depending on cellular factors [11].

The distinction between pH-dependent and pH-independent entry has profound implications for viral tropism engineering. For pH-dependent viruses, any receptor that mediates endocytosis can potentially trigger fusion, making tropism redirection relatively straightforward through the engineering of envelope proteins to bind desired target molecules [8]. Conversely, pH-independent entry typically requires a specific sequence of receptor interactions to properly activate the fusion machinery, making tropism redirection more challenging as it requires preserving the complex signaling between binding and fusion activation domains [8].

Experimental Analysis of Entry Mechanisms

Methodologies for Studying Viral Entry

Understanding viral entry mechanisms requires a multifaceted experimental approach that combines structural biology, biochemical assays, and cell-based systems. Recent advances in structural biology techniques, particularly cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), have revolutionized our understanding of virus-receptor interactions by providing high-resolution structures of viral particles in complex with cellular receptors [15]. For AAV vectors, cryo-EM has detailed interactions with glycan "attachment factors" and protein receptors, revealing how different serotypes utilize distinct binding sites on their capsids to engage receptors [15]. Similarly, structural studies of envelope proteins like the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein have revealed dynamic conformational states ("open" and "closed") that regulate receptor accessibility and fusion activation [14].

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods for Studying Viral Entry Mechanisms

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Notable Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy | High-resolution structure determination of viral proteins and complexes with receptors | Atomic-level details of receptor binding sites; conformational changes in fusion proteins |

| Cell-based Assays | Infectivity assays, cell-cell fusion assays, RNA interference screens | Functional analysis of entry pathways; identification of essential host factors | Distinction between pH-dependent and independent entry; identification of co-receptors |

| Biochemical Approaches | Virus-liposome fusion assays, co-immunoprecipitation, surface plasmon resonance | Analysis of lipid mixing kinetics; protein-protein interactions; binding affinity measurements | Characterization of fusion intermediates; quantification of receptor binding kinetics |

| Single-Virus Tracking | Fluorescence video microscopy, single-particle tracking | Real-time visualization of virus entry and trafficking | Dynamics of virus-receptor interactions; entry pathway kinetics |

Functional studies of viral entry employ various cell-based assays that measure infectivity under different experimental conditions. The use of chemical inhibitors that specifically block different entry pathways has been instrumental in characterizing entry mechanisms [11]. For instance, weak bases like ammonium chloride or specific vATPase inhibitors such as Bafilomycin A can block pH-dependent entry by neutralizing endosomal pH, while inhibitors of specific proteases can block entry of viruses that require proteolytic activation [11]. Pseudoparticles—viral cores incorporating heterologous envelope proteins—have proven particularly valuable as they allow study of entry mechanisms in a safer, more flexible system that can be adapted for high-throughput screening of entry inhibitors [10].

Genetic approaches, including RNA interference screens and CRISPR-based gene editing, enable systematic identification of host factors essential for viral entry. These methods have revealed that beyond primary receptors, numerous co-factors and intracellular proteins play critical roles in viral entry, often by facilitating trafficking to the appropriate cellular compartment or triggering necessary conformational changes in viral proteins [10]. For some viruses, these intracellular factors can be as important as surface receptors in determining tropism, explaining why some viruses exhibit different entry mechanisms in different cell types [10] [11].

Engineering Viral Tropism

The ability to redirect viral tropism through rational engineering of capsid or envelope proteins has significant implications for gene therapy, vaccine development, and targeted viral therapies. The strategies for tropism engineering differ significantly between enveloped and non-enveloped viruses, reflecting their distinct entry mechanisms.

For enveloped viruses, pseudotyping—the process of incorporating heterologous envelope proteins onto viral cores—represents a powerful approach to alter tropism [7]. This technique takes advantage of the natural fusogenic properties of envelope proteins while redirecting their binding specificity. For example, lentiviral vectors are commonly pseudotyped with Vesicular Stomatitis Virus G (VSV-G) protein to broaden their tropism, or with specific targeting domains to restrict transduction to particular cell types [7]. Similarly, engineered baculovirus pseudotyped with VSV-G glycoprotein (BacMam) has been used to deliver genes to mammalian brains [7].

More sophisticated engineering approaches involve direct modification of envelope proteins to eliminate natural receptor binding while introducing new targeting specificities. For pH-dependent viruses like Sindbis virus, extensive mutation of the original receptor-binding regions combined with conjugation of targeting ligands (such as single-chain antibodies, peptides, or non-covalently conjugated antibodies) has successfully redirected tropism to desired cell types while reducing transduction of untargeted tissues [8]. For pH-independent viruses like measles, successful redirection has required more precise engineering to preserve the signaling between binding and fusion activation domains, typically achieved through C-terminal conjugation of targeting ligands to the binding protein while mutating natural receptor interactions [8].

For non-enveloped viruses like AAV, tropism engineering focuses on modifying the capsid proteins through rational design, directed evolution, or computational approaches including machine learning [7]. Rational design strategies may involve inserting targeting peptides into surface-exposed loops of the capsid protein, while directed evolution approaches subject diverse capsid libraries to selective pressure for desired tropism characteristics [7]. These engineering efforts have produced AAV variants with enhanced specificity for particular tissues, such as the central nervous system, or the ability to evade pre-existing neutralizing antibodies [7] [15].

Research Reagents and Tools

The study and engineering of viral entry mechanisms relies on a specialized toolkit of reagents and methodologies. The table below outlines key resources essential for researchers working in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Viral Entry and Tropism

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry Inhibitors | Bafilomycin A, Concanamycin A, Ammonium Chloride | Inhibition of pH-dependent entry; mechanism studies | Specificity for vATPase vs. general pH disruption; cellular toxicity |

| Protease Inhibitors | Camostat, E64d, Leupeptin | Blocking proteolytic activation of viral proteins | Specificity for serine vs. cysteine proteases; cellular permeability |

| Pseudotyping Systems | VSV-G, Sindbis envelope, Modified measles H | Tropism expansion or restriction; safety studies | Compatibility with viral core; titer implications; biosafety level |

| Cell Lines | Engineered receptor-expressing lines, Primary cell cultures | Tropism profiling; receptor identification | Physiological relevance; replication permissiveness; availability |

| Structural Tools | Cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, Surface plasmon resonance | Molecular mechanism studies; binding affinity | Resolution limitations; sample requirements; technical expertise |

| Animal Models | Humanized mice, Transgenic receptor models | In vivo tropism validation; therapeutic efficacy | Species-specific receptor differences; immune competence; cost |

Advanced vector systems like virus-like particles (VLPs) have emerged as particularly valuable tools for studying viral entry mechanisms while minimizing safety concerns. VLPs are streamlined viral vectors that retain the structural proteins necessary for assembly and entry but lack viral genetic material, making them replication-incompetent [9]. Recent engineering efforts have developed SFV-based VLPs with minimal viral components, preserving only the capsid and envelope proteins while eliminating all viral protein-coding sequences from the delivered cargo [9]. These VLPs can be packaged with various cargo types including mRNA, protein, or ribonucleoprotein complexes, making them versatile tools for studying entry mechanisms and testing targeting strategies [9].

The development of high-throughput screening approaches has accelerated the identification of viral entry inhibitors and the engineering of vectors with altered tropism. Pseudoparticle-based neutralization assays enable rapid screening of compound libraries or serum samples for entry inhibitors, while directed evolution platforms using diverse capsid or envelope protein libraries facilitate selection of variants with desired tropism characteristics [10] [7]. These approaches are increasingly complemented by computational methods, including machine learning algorithms that can predict the tropism of viral variants based on sequence or structural features, guiding rational design efforts [7].

The intricate relationship between viral capsid/envelope proteins and their cellular targets represents both a fundamental biological process and a critical opportunity for therapeutic intervention. The structural and functional insights gained from comparative analyses of different viral entry systems have accelerated the development of viral vectors with enhanced targeting capabilities for gene therapy, vaccine development, and targeted oncolytic treatments. As structural biology techniques continue to reveal atomic-level details of virus-receptor interactions, and engineering methodologies become increasingly sophisticated, the precision with which we can direct viral vectors to specific cellular targets will continue to improve. The integration of mechanistic understanding with advanced engineering approaches promises to yield the next generation of viral vectors with optimized tropism profiles for diverse biomedical applications.

Viral vectors are indispensable tools in gene therapy and biomedical research, with their efficacy and safety profiles fundamentally shaped by their genome architecture. The functional components of a viral vector genome—the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), the packaging signal (Ψ), and the expression cassette—act in concert to dictate vector performance, including production efficiency, packaging capacity, tropism, and transgene expression levels. Understanding the structure-function relationships of these components across different viral vector platforms is crucial for optimizing their design for therapeutic applications. This guide provides a comparative analysis of genome architectures for three predominant viral vector systems: Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV), Adenovirus (Ad), and Lentivirus (LV), leveraging recent experimental data to objectively compare their performance.

Core Components of Viral Vector Genomes

The genome architecture of viral vectors comprises several critical elements, each with a distinct function.

Inverted Terminal Repeats (ITRs): These are short, palindromic DNA sequences found at the ends of the viral genome. They serve as origins of replication, are essential for packaging the genome into the capsid, and can influence genome persistence and nuclear processing [1] [16] [17]. In AAV, ITRs can form T-shaped hairpins crucial for replication and are prone to structural instability during plasmid propagation in bacteria [18].

Packaging Signal (Ψ): This is a cis-acting RNA element, often with complex secondary structures, that is specifically recognized by viral proteins. It ensures the selective incorporation of the vector genome, rather than cellular RNA, into the newly formed viral capsid or virion [19] [20].

Expression Cassette: This component carries the genetic payload, typically consisting of a promoter, the transgene coding sequence, and a polyadenylation signal. Its design, including the choice of regulatory elements, directly impacts the level, specificity, and duration of transgene expression [21].

Table 1: Core Functional Elements Across Viral Vector Platforms

| Vector Platform | Genetic Material | ITR Function | Packaging Signal (Ψ) Characteristics | Key Viral Proteins for Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Origin of replication, packaging signal [16] [17] | Located within the ITRs themselves [16] | Rep proteins [22] |

| Adenovirus (Ad) | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Origin of replication, primase-independent replication [1] | Located at the left arm of the genome, distinct from ITRs [1] | Packaging proteins (IVa2, L4 33K, L1 52/55K, L4 22K) [1] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) | Flanked by Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs) for integration | Structured RNA element between 5' LTR and gag, extends into gag [19] [20] | Nucleocapsid (NC) domain of Gag polyprotein [20] |

Comparative Analysis of Genome Architectures

Inverted Terminal Repeats (ITRs)

ITRs are a hallmark of AAV vectors but differ significantly from the terminal repeats of other systems.

AAV ITRs: The AAV ITR is approximately 145 base pairs (bp) and forms a stable, T-shaped hairpin structure. It contains Rep protein binding sites (RBE) and a terminal resolution site (trs) essential for replication [17]. A unique feature is its ability to exist in two configurations, "flip" and "flop," which arise during replication [17]. These structures are notoriously unstable during standard plasmid propagation in bacteria, often suffering from deletions that can compromise viral packaging efficiency if not carefully monitored [18].

Adenovirus ITRs: Adenovirus possesses much larger ITRs, ranging from 30 to 371 bp, which form hairpin-like structures at the termini of its linear dsDNA genome. These ITRs function as origins of replication and self-priming structures for DNA synthesis but are distinct from the packaging signal [1].

Lentivirus LTRs: Lentiviruses, as retroviruses, are defined by their Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs). These are much larger sequences that flank the viral RNA genome and are essential for the reverse transcription, integration, and regulation of viral gene expression. The packaging signal, however, is separate and located in the 5' untranslated region [19].

Packaging Signals (Ψ)

The location, structure, and recognition of packaging signals vary considerably, influencing vector specificity and efficiency.

Lentivirus Packaging Signal: The lentiviral Ψ is a complex, structured RNA element located between the 5' LTR and the beginning of the gag gene. In HIV-1, it consists of four major stem-loop structures (SL1-SL4) [20]. SL1 contains the dimerization initiation site, while SL3 is a major binding site for the nucleocapsid (NC) protein. This specific interaction between the Ψ RNA and the Gag polyprotein is critical for the selective packaging of full-length genomic RNA into budding virions [19] [20]. Mutations in these stem-loops can severely reduce packaging efficiency [19].

Adenovirus Packaging Signal: The adenovirus packaging signal (ψ) is a short, discrete DNA sequence located near the left end of its linear genome, adjacent to the ITR. It is recognized by a complex of viral packaging proteins, including IVa2 and L4 22K, which direct the genome into the pre-formed capsid [1].

AAV Packaging Signal: For AAV, the packaging signal is not a separate element but is intrinsically contained within the ITR sequences. The ITRs are recognized by the large Rep proteins (Rep78/68), which are essential for both genome replication and the translocation of the ssDNA genome into pre-assembled capsids [22] [16].

Diagram 1: Comparative overview of packaging signal recognition across AAV, adenovirus, and lentivirus platforms.

Expression Cassettes & Packaging Capacity

The design of the expression cassette is critical for transgene expression and is constrained by the vector's packaging capacity.

AAV Cassette Design and Capacity: AAV has a strict packaging limit of approximately 4.7 kb for its single-stranded DNA genome [21] [16]. This limited capacity makes the size of every element in the expression cassette critical. Research has shown that using shorter regulatory elements can free up space for larger transgenes without sacrificing expression efficiency. For instance, replacing the standard WPRE (600 bp) with a shorter WPRE3 (247 bp) and using the SV40 late polyadenylation signal (creating a cassette called CW3SL) maintained high expression levels while reducing the overall cassette size. This allowed for the successful packaging and functional expression of a large p110γ-EGFP fusion transgene (5.2 kb) that exceeded the capacity of the original CWB cassette [21]. Furthermore, genome size significantly impacts AAV quality. Systematic studies using "stuffer" sequences to create genomes from 2.0 kb to 5.0 kb demonstrated that yields and bioactivity decrease as size increases. Notably, genomes that are too small (<2.5 kb) are prone to overfilling (packaging of oversized DNA), while those that are too large (>4.5 kb) suffer from increased truncation, with the ideal "right-size" being 3.0–3.5 kb [23].

Adenovirus and Lentivirus Capacity: Both adenovirus and lentivirus offer significantly larger packaging capacities. Adenovirus can accommodate up to 36 kb of foreign DNA, making it suitable for delivering large or multiple transgenes [1]. Lentivirus can typically package RNA genomes of around 8-10 kb, which also provides substantial flexibility for complex expression cassettes [19].

Table 2: Impact of AAV Genome Size on Key Production Metrics [23]

| Genome Size (kb) | Relative Total Yield (vg) | Particle Population | Relative Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 - 2.5 | High (Reference) | Prone to overfilling (oversized genomes) | High |

| 3.0 - 3.5 | Moderate | Optimal (minimal partial/overfilled) | High |

| 4.5 - 5.0 | Low (≤50% of 2.0 kb yield) | Increased partial/truncated genomes | Reduced |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Analyzing AAV Genome Packaging Heterogeneity

Objective: To characterize the heterogeneity of packaged AAV genomes, including the presence of full-length, partial, and oversized genomes, using charge detection-mass spectrometry (CD-MS) and alkaline gel electrophoresis [22] [23].

- AAV Production and Purification: Produce rAAV vectors via transient transfection of HEK293 cells (adherent or suspension) using a triple-plasmid system (rep/cap, pHelper, and ITR-flanked transgene plasmid). Purify crude vectors using iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation [22] [23].

- Genome Release and Alkaline Gel Electrophoresis:

- Mix 2.5 x 10^10 vector genomes (vg) with an alkaline loading buffer (e.g., containing EDTA and NaOH).

- Load onto a 1% agarose gel prepared and run in an alkaline running buffer (e.g., 30 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA).

- Run the gel at a constant voltage, then neutralize, stain with ethidium bromide, and visualize under UV light. This denatures the ssDNA and allows size-based separation to resolve full-length from truncated genomes [23].

- Charge Detection-Mass Spectrometry (CD-MS):

- Desalt the AAV sample into 200 mM ammonium acetate solution.

- Introduce the sample into the CD-MS instrument. This technique measures the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio and the charge of individual particles simultaneously to determine their absolute mass.

- Analyze thousands of particles to generate a mass histogram. This allows for the direct quantification of the proportion of empty capsids (low mass), full capsids (expected mass), and capsids containing truncated or oversized genomes (deviating masses) [22].

Protocol: Evaluating Modified Expression Cassette Efficiency

Objective: To compare the transgene expression efficiency of a newly designed, smaller expression cassette against a standard cassette in vivo [21].

- Vector Construction: Clone the transgene (e.g., EGFP) into both the standard (e.g., CWB) and the modified, smaller (e.g., CW3SL) AAV expression cassettes, each flanked by ITRs.

- Co-injection in vivo: Package each construct into the desired AAV serotype. Prepare a mixture containing the test vector (e.g., CWB-EGFP or CW3SL-EGFP) and a control vector (e.g., CWB-tdTomato) to control for injection variability.

- Stereotaxic Injection: Anesthetize the animal (e.g., mouse) and perform stereotaxic surgery to inject the virus mixture into the target brain region (e.g., hippocampal CA1).

- Tissue Processing and Analysis: After a suitable expression period, perfuse and fix the brain. Section the tissue and image the injection site using fluorescence microscopy.

- Quantitative Analysis: Measure the mean fluorescence intensity for both EGFP and tdTomato in the same region of interest. Calculate a normalized EGFP expression value (e.g., EGFP intensity / tdTomato intensity) for each animal. Compare the normalized expression between the group injected with the standard cassette and the group injected with the modified cassette using statistical tests (e.g., t-test) [21].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for analyzing AAV genome packaging heterogeneity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research and development in viral vector genome architecture rely on specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Viral Vector Genome Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| ITR-Stable Bacterial Strains (e.g., SURE2, Stabl3, proprietary strains) | Plasmid propagation while minimizing ITR deletions [18] | Standard cloning strains (e.g., DH5α) are not suitable; strain performance can vary by AAV plasmid. |

| Specialized ITR Sequencing Service (e.g., AAV-ITR sequencing) | High-fidelity sequencing through stable hairpin structures to confirm ITR integrity [18] | Standard Sanger sequencing fails in ITR regions; robust protocols are required for accurate QC. |

| Non-Coding "Stuffer" DNA | Used to systematically adjust AAV genome size to an optimal range (e.g., 3.0-3.5 kb) to minimize truncated/overfilled particles [23] | The nucleotide sequence itself can impact yield and bioactivity; sequences must be carefully selected and de-optimized. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Assays | Absolute quantification of vector genome titer and integrity (e.g., using ITR- vs. transgene-specific probes) [23] | More precise than qPCR for detecting small differences and quantifying heterogeneous populations. |

| Nucleocapsid (NC) Protein Expression Systems | For in vitro studies of lentiviral Ψ RNA-protein interactions and packaging efficiency [19] [20] | Critical for mapping specific binding domains and validating stem-loop mutations. |

The genome architecture of viral vectors is a primary determinant of their functionality and therapeutic potential. AAV, adenovirus, and lentivirus platforms exhibit fundamental differences in their ITRs, packaging signals, and optimal expression cassette design, leading to distinct performance trade-offs. AAV's strength lies in its non-pathogenic nature and long-term expression but is constrained by a limited ~4.7 kb capacity, which necessitates careful optimization of every base pair in the expression cassette. Adenovirus offers a massive capacity for large transgenes, while lentivirus provides the unique ability to integrate into the host genome. As the field advances, the precise engineering of these genomic components—from designing smaller, more potent expression cassettes to optimizing genome size and ensuring ITR integrity—will be paramount in developing next-generation gene therapies with improved efficacy and safety profiles.

The study of vector-host interactions represents a critical frontier in molecular biology and therapeutic development, focusing on the complex mechanisms by which delivery vectors navigate cellular barriers to transport their cargo into cells. These interactions encompass the initial attachment to cell surfaces, receptor-mediated internalization, intricate intracellular trafficking through endosomal pathways, and ultimately, the delivery of genetic or therapeutic materials to their intended subcellular destinations. Understanding these processes is fundamental for advancing viral vector structure-function studies and optimizing next-generation delivery systems for gene therapy and vaccination. The efficiency of these entry pathways directly influences transduction success, therapeutic efficacy, and safety profiles across diverse vector platforms [24] [25] [26].

Current research leverages sophisticated engineering approaches to decipher and manipulate these interactions, with particular emphasis on receptor binding specificity, endosomal escape mechanisms, and navigation of intracellular barriers. The field has evolved from utilizing native viral vectors to developing engineered pseudotypes and synthetic systems that combine favorable attributes from multiple platforms. These advances require precise experimental methodologies to quantify entry efficiency, map intracellular routes, and compare performance across vector alternatives—the essential focus of this comparative guide for research scientists and drug development professionals [24] [26] [16].

Comparative Analysis of Vector Platforms

Viral Vector Systems

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Major Viral Vector Platforms

| Vector Platform | Genetic Material | Cargo Capacity | Primary Entry Receptors | Intracellular Trafficking | Transgene Expression | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Single-stranded DNA | ~4.7 kb | AAVR, HGFR, HSPG | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, endosomal escape, nuclear import | Onset: Slow (weeks) Duration: Long-term (episomal) | Low immunogenicity; Broad tissue tropism; Established manufacturing | Limited cargo capacity; Pre-existing immunity; Potential genotoxicity |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Single-stranded RNA | ~8 kb | VSV-G: LDLR; Others: specific to pseudotype | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, reverse transcription in cytoplasm, nuclear import via active transport | Onset: Moderate (days) Duration: Long-term (integrating) | Transduces dividing/non-dividing cells; Stable integration; High titer production | Insertional mutagenesis risk; Complex manufacturing; Higher immunogenicity |

| Adenoviral Vectors | Double-stranded DNA | ~8-36 kb (depending on generation) | CAR, CD46, DSG2, HSPG | Clathrin- and caveolin-independent endocytosis, endosomal escape, nuclear import via nuclear pores | Onset: Rapid (hours) Duration: Short-term (episomal) | High transduction efficiency; Rapid expression; Large cargo capacity | Strong immune response; Pre-existing immunity; Toxicity at high doses |

| Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors | Single-stranded RNA | ~8 kb | Dependent on envelope protein (VSV-G, Rabies-G, LCMV-G, etc.) | Determined by envelope protein; typically clathrin-mediated endocytosis | Onset: Moderate (days) Duration: Long-term (integrating) | Broadened tropism; Enhanced safety (Biosafety Level 2); Customizable targeting | Potential for recombinant events; Lower titer than some platforms; Complex characterization |

Viral vectors represent the most mature delivery platforms, with distinct entry pathways and intracellular trafficking patterns that directly influence their experimental and therapeutic applications. AAV vectors demonstrate particularly complex entry mechanisms involving attachment to primary receptors like HSPG, coreceptors (AAVR, HGFR), and internalization via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Their single-stranded DNA genome requires second-strand synthesis before gene expression, contributing to slower onset but enabling long-term episomal persistence in non-dividing cells [16]. The recent discovery of AAV's association with unexplained hepatitis in children highlights the importance of continued investigation into its host interactions [16].

Lentiviral vectors, particularly when pseudotyped with various envelope glycoproteins, offer remarkable flexibility in host range and entry pathways. VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviruses enter via LDL receptor family members and follow clathrin-mediated endocytosis, with their pre-integration complex actively transported into the nucleus through nuclear pores. This capability to transduce non-dividing cells, combined with stable integration, makes them invaluable for long-term gene expression studies but introduces concerns about insertional mutagenesis that must be carefully managed in therapeutic contexts [24] [26].

Adenoviral vectors exhibit rapid entry and gene expression kinetics, utilizing CAR or other receptors depending on serotype, with internalization occurring through clathrin- and caveolin-independent mechanisms. Their efficient endosomal escape and nuclear import capabilities contribute to high transduction efficiencies but are counterbalanced by significant immune activation that limits repeated administration. The emergence of rare but serious adverse events like vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) in adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccines underscores the critical importance of understanding immune responses to viral vector platforms [26].

Emerging Non-Viral Delivery Systems

Table 2: Non-Viral Vector Delivery Mechanisms

| Delivery System | Composition | Cargo Type | Entry Mechanisms | Intracellular Trafficking | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) | Short peptides (5-30 aa) with basic/non-polar residues | Proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules | Direct penetration, macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae endocytosis | Endosomal entrapment, endosomal escape varies by peptide | Low immunogenicity; Versatile cargo conjugation; Modular design | Endosomal entrapment; Limited target specificity; Variable efficiency |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, PEG-lipids | mRNA, siRNA, pDNA | Endocytosis (multiple pathways), membrane fusion | Endosomal trafficking, endosomal escape via ionization | Clinical validation; Scalable manufacturing; Tunable properties | Cytotoxicity at high doses; Liver-dominated tropism; Storage stability |

| Cationic Polymers | Polyethylenimine (PEI), chitosan, dendrimers | pDNA, siRNA | Electrostatic interactions with membranes, endocytosis | Proton sponge effect for endosomal escape | High cargo capacity; Chemical versatility; Self-assembly | Cytotoxicity; Polydispersity; Complex characterization |

Non-viral vector systems have emerged as promising alternatives addressing limitations of viral platforms, particularly regarding immunogenicity, cargo capacity, and manufacturing complexity. Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) represent one of the most versatile non-viral delivery strategies, utilizing short amino acid sequences enriched in basic or non-polar residues to facilitate cellular uptake. These peptides are classified as amphipathic, cationic, anionic, or hydrophobic based on their sequence properties and mechanism of membrane interaction [25]. Since the discovery of the HIV-1 TAT peptide in the 1980s, CPP development has expanded to include diverse families with applications ranging from drug delivery to vaccine development [25].

CPPs employ two primary entry mechanisms: direct penetration through membrane disruption and various endocytic pathways. Amphipathic CPPs like Transportan can directly cross membranes, while cationic CPPs such as TAT and Penetratin primarily utilize macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated, and caveolae-dependent endocytosis. A critical bottleneck for CPP efficacy is endosomal entrapment, where cargo remains sequestered within endosomes and cannot reach cytoplasmic or nuclear targets. Ongoing research focuses on enhancing endosomal escape through the incorporation of fusogenic or membrane-disruptive elements [25].

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have gained significant attention following their successful implementation in COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, demonstrating clinical validation of non-viral gene delivery. LNPs typically enter cells through endocytosis, with their ionizable lipids undergoing protonation in acidic endosomal environments, leading to membrane disruption and cargo release into the cytoplasm. While LNPs offer advantages in manufacturing scalability and reduced immunogenicity compared to viral vectors, they often exhibit liver-dominated tropism and can provoke inflammatory responses at higher doses [27].

Experimental Methodologies for Entry Pathway Analysis

Pseudotyped Virus Neutralization Assay

Purpose: To evaluate vector entry specificity and neutralizing antibody activity by measuring infection inhibition using engineered pseudoviruses bearing specific envelope proteins [24].

Detailed Protocol:

- Vector Production: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with (a) packaging plasmid containing structural genes, (b) genomic plasmid with reporter gene (luciferase or GFP), and (c) envelope plasmid bearing glycoprotein of interest using polyethylenimine (PEI) or calcium phosphate transfection [24].

- Harvest and Purification: Collect viral supernatant 48-72 hours post-transfection, concentrate by ultracentrifugation or PEG precipitation, and resuspend in PBS buffer. Determine viral titer by quantitative PCR or reporter assay [24].

- Neutralization Reaction: Incubate serial dilutions of test sera or monoclonal antibodies with fixed quantity of pseudotyped virus (typically 1×10^5 IU) for 90 minutes at 37°C in cell culture medium [24].

- Cell Infection: Add virus-antibody mixture to target cells (HEK293T, Vero, or other permissive cells) in 96-well plates, centrifuge at 800×g for 30 minutes to enhance infection, then incubate for 48-72 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [24].

- Detection and Analysis: Measure reporter gene expression (luminescence for luciferase, fluorescence for GFP) using plate reader. Calculate neutralization percentage relative to virus-only controls, with 50% neutralization titer (NT50) determined by non-linear regression analysis [24].

Key Applications: Vaccine immunogenicity assessment, monoclonal antibody characterization, serological surveillance, and viral entry mechanism studies. This method enables safe investigation of highly pathogenic viruses under BSL-2 conditions by using replication-incompetent pseudoviruses [24].

Intracellular Trafficking and Colocalization Studies

Purpose: To visualize and quantify vector transport through intracellular compartments following entry, providing spatial and temporal resolution of trafficking pathways.

Detailed Protocol:

- Vector Labeling: Fluorescently label viral vectors or non-viral nanoparticles using chemical tags (Alexa Fluor dyes, Cy dyes) or genetic incorporation of fluorescent proteins (GFP, mCherry). For chemical labeling, use amine-reactive dyes to modify capsid proteins while preserving functionality [25] [16].

- Compartment Staining: Employ organelle-specific markers for definitive colocalization analysis: LysoTracker for acidic compartments, MitoTracker for mitochondria, ER-Tracker for endoplasmic reticulum, and immunostaining for specific proteins (LAMP1 for late endosomes/lysosomes, EEA1 for early endosomes, GM130 for Golgi) [28].

- Live-Cell Imaging: Incubate labeled vectors with cells on glass-bottom dishes, then image at predetermined intervals (5-60 minutes) using confocal or spinning disk microscopy. Maintain cells at 37°C with 5% CO₂ during imaging. Use low laser power to minimize phototoxicity [25] [28].

- Inhibitor Studies: Apply specific pharmacological inhibitors to dissect trafficking pathways: chloroquine for endosomal acidification inhibition, wortmannin for macropinocytosis inhibition, dynasore for clathrin-mediated endocytosis blockade [25].

- Image Analysis: Quantify colocalization using Pearson's correlation coefficient or Manders' overlap coefficient with ImageJ or specialized software. Track particle movement to determine transport velocities and directional persistence [25] [28].

Key Applications: Mapping intracellular barriers to gene delivery, identifying trafficking bottlenecks, evaluating engineered vectors with enhanced endosomal escape capabilities, and studying pathogen hijacking of host transport machinery [25] [28].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Vector-Host Interaction Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging Systems | pMD2.G (VSV-G), pSPAX2, psPAX2, pAdVAntage | Lentiviral and pseudotyped vector production | Second/third-generation systems improve biosafety by splitting viral genes |

| Envelope Plasmids | VSV-G, Rabies-G, LCMV-G, Ebola-GP, SARS2-S | Pseudotyping to alter tropism and entry pathways | Glycoprotein choice determines receptor usage and species tropism |

| Reporter Genes | Firefly luciferase, NanoLuc, GFP, mCherry, LacZ | Quantification of entry and transduction efficiency | Luciferase offers dynamic range; fluorescence enables single-cell analysis |

| Endocytosis Inhibitors | Chlorpromazine (clathrin), Filipin (caveolin), Wortmannin (macropinocytosis), Dynasore (dynamin) | Mechanistic studies of entry pathways | Concentration optimization critical for specificity and cell viability |

| Organelle Markers | LysoTracker, MitoTracker, ER-Tracker, CellLight BacMams | Intracellular trafficking and compartment colocalization | Live-cell compatible dyes vs. immunostaining for fixed samples |

| Neutralization Assay Components | Positive control sera, reference standards, cell lines (HEK293T, Vero, etc.) | Serological assessment and entry blockade studies | Standardized reference materials essential for cross-study comparisons |

| Engineering Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 for receptor knockout, Site-directed mutagenesis kits | Structure-function studies of viral envelopes and host factors | Enables definitive identification of essential receptors and domains |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for rigorous investigation of vector-host interactions. Packaging systems have evolved through multiple generations to enhance safety, with third-generation lentiviral systems separating viral genes across multiple plasmids to minimize recombination risk. Similarly, AAV production employs Rep/Cap and helper plasmids to provide essential viral functions in trans while preventing replication-competent virus formation [24] [16].

Pseudotyping strategies dramatically expand experimental flexibility, allowing researchers to match envelope proteins with specific scientific questions. VSV-G remains the most widely used envelope for lentiviral vectors due to its broad tropism and particle stability, while specialized glycoproteins like Rabies-G enable enhanced neuronal transduction, and LCMV-G facilitates targeting of hematopoietic cells. The choice of envelope directly determines receptor usage and consequently the entry pathway utilized [24] [26].

Mechanistic studies rely heavily on specific pharmacological inhibitors and genetic approaches to dissect entry pathways. While small molecule inhibitors provide convenient reversible blockade of specific routes, genetic knockout of receptors using CRISPR/Cas9 offers definitive identification of essential host factors. Combined approaches typically yield the most robust mechanistic insights, controlling for potential off-target effects of pharmacological agents [25] [16].

Visualizing Vector Entry Pathways

Vector Entry and Intracellular Trafficking Pathways

This comprehensive visualization maps the sequential stages of vector-host interactions, from initial attachment through intracellular trafficking to final gene expression. The pathway highlights critical bottlenecks including endosomal escape—where many vectors fail—and the degradative lysosomal route that represents a common fate for internalized vectors. Successful gene delivery requires navigation through each hierarchical step, with different vector platforms exhibiting distinct efficiencies at each transition point [24] [25] [16].

Pseudotyped Virus Neutralization Assay Workflow

This experimental workflow details the methodology for producing and applying pseudotyped viruses to study entry mechanisms and neutralizing responses. The process begins with co-transfection of three essential plasmid components—packaging, genomic, and envelope—into producer cells, followed by virus harvest, concentration, and quality control. The neutralization assay proper involves pre-incubation of pseudoviruses with test antibodies or sera before infection of target cells, with quantitative readout via reporter genes enabling precise calculation of neutralization potency [24]. This methodology provides a safe and versatile platform for studying entry of highly pathogenic viruses under BSL-2 conditions.

The systematic comparison of vector entry pathways and intracellular trafficking mechanisms reveals a complex landscape of biological interactions that directly influence gene delivery efficiency and therapeutic outcomes. Viral vectors, particularly lentiviral and AAV platforms, demonstrate sophisticated evolved mechanisms for navigating cellular barriers but face challenges related to immunogenicity and manufacturing complexity. Non-viral alternatives, including CPPs and LNPs, offer advantages in safety profile and production scalability but must overcome inefficiencies in endosomal escape and tissue-specific targeting.

The experimental methodologies outlined—particularly pseudotyped virus neutralization assays and intracellular trafficking studies—provide robust frameworks for quantifying vector performance and elucidating entry mechanisms. These approaches enable direct comparison across platforms under standardized conditions, facilitating evidence-based selection of appropriate vector systems for specific research or therapeutic applications. As the field advances, integration of structural insights from viral vector studies with innovative bioengineering approaches will likely yield next-generation delivery systems with enhanced specificity, reduced immunogenicity, and improved clinical potential.

Future directions will undoubtedly focus on overcoming persistent barriers, particularly endosomal entrapment, while developing increasingly sophisticated targeting strategies that maximize therapeutic impact while minimizing off-target effects. The continued refinement of the experimental tools and reagents described in this guide will play an essential role in these developments, providing the fundamental infrastructure for advances in vector-host interaction research.

Structural Basis for Transgene Expression and Persistence

The structural architecture of viral vectors is a fundamental determinant of their efficacy in gene therapy, directly influencing the stability and longevity of transgene expression. These engineered vectors leverage the natural infection mechanisms of viruses but are modified with specific structural components to enhance safety and performance. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the relationship between vector design—encompassing capsid proteins, genome elements, and epigenetic regulators—and functional outcomes is crucial for developing next-generation therapies [29]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major viral vector platforms, supported by experimental data, to inform rational vector selection and engineering for specific therapeutic applications.

Vector Platforms: A Structural and Functional Comparison

The structural composition of viral vectors dictates their transduction efficiency, cargo capacity, genomic integration behavior, and ultimately, the persistence of transgene expression. Key features of prevalent viral vector systems are systematically compared in Table 1.

Table 1: Structural and Functional Comparison of Major Viral Vector Platforms

| Vector Type | Genetic Material & Packaging Capacity | Structural Features Determining Tropism | Genome Persistence Mechanism | Duration of Expression | Key Structural Advantages | Key Structural Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV | Single-stranded DNA, <4.7 kb [30] | Capsid proteins (VP1-3) determining receptor binding (e.g., AAVR, HSPG) [30] | Episomal persistence in non-dividing cells [30] [29] | Long-term (months to years) [31] [30] | Low immunogenicity; Favorable safety profile [31] [30] | Limited packaging capacity [31] [30] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | Single-stranded RNA, ~9-10 kb [32] | Envelope glycoproteins (e.g., VSV-G) for broad tropism | Integration into host genome [32] [29] | Stable, long-term in dividing and non-dividing cells [32] | Large cargo capacity; Stable integration [32] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis [29] |

| Adenovirus (Ad) | Double-stranded DNA, up to 36 kb [32] [29] | Fiber knob proteins for receptor binding (e.g., CAR, CD46) [32] | Episomal (non-integrating) [32] [29] | Transient (weeks to months) [32] | Very high transduction efficiency; Large capacity [32] [29] | Strong immune response [32] [29] |

| Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) | Double-stranded DNA, >30 kb [33] | Glycoproteins on the envelope for neurotropism | Episomal persistence in neuronal nuclei [33] | Long-term (demonstrated for 11.7 months) [33] | Very large packaging capacity; Natural neurotropism [33] | Complex genome requiring multiple deletions [33] |

The following diagram illustrates the general mechanism of transgene expression and persistence shared by many viral vector types, highlighting key structural components and intracellular processes.

Diagram Title: General Mechanism of Viral Vector Transgene Expression

Experimental Data on Expression Persistence

Quantitative Analysis of Vector Performance

Strategic engineering of vector structures has yielded significant improvements in the duration and level of transgene expression. Experimental data from recent studies provide direct comparisons of performance across different vector designs and platforms.

Table 2: Experimental Data on Transgene Expression Persistence Across Vector Platforms

| Vector Type & Study Details | Experimental Model | Key Structural Intervention | Expression Duration | Expression Level/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rdHSV-1 with insulators [33] | Rodent brain | Combination of viral (CTRL2, CTRS3) and cellular (tRNA, S/MAR) insulators at ICP4 locus | 11.7 months | Significantly enhanced and stable neuronal expression |

| AAV for Retinal Therapy [30] | Human clinical trials (LCA2) | Subretinal delivery of AAV2 with RPE65 transgene | >3 years (Phase III) | Significant visual improvement (p=0.001) |

| Lentivirus for SCID-X1 [34] | Human clinical trial (n=9) | Self-inactivating (SIN) γ-retroviral vector with internal EF-1α promoter | >33 months median follow-up | Restored immune function in 8/9 patients |

| Adenovirus for Hemophilia B [34] | Human clinical trial | AAV8 capsid with codon-optimized, self-complementary FIX genome | Transient (limited by immunity) | Therapeutic FIX levels achieved |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Insulator Function in HSV-1 Vectors

The following methodology details the approach used to assess the impact of insulator elements on transgene persistence in replication-defective HSV-1 vectors, as described in the search results [33]. This protocol serves as a template for similar structural-function studies.

Objective: To evaluate the effect of combined viral and cellular insulators on long-term transgene expression from specific loci (LAT and ICP4) in rdHSV-1 vectors in neuronal cells.

Materials and Reagents:

- rdHSV-1 Backbone Vector (JΔNI8): Deficient in IE genes (ICP0, ICP4, ICP27) and vhs (UL41) to eliminate cytotoxicity and inflammatory responses [33].

- Gateway Cloning System: For insertion of transgene cassettes into designated viral loci [33].

- Reporter Cassette: CAG promoter-driven ZsGreen and firefly luciferase (fLuc) separated by T2A self-cleaving peptide [33].

- Insulator Elements: Viral insulators (LAP2/LATP2, CTRL2, CTRS3) and cellular insulators (tRNA genes, S/MARs) [33].

- Cell Lines: U2OS-ICP4/27 complementing cell line for vector production; Differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells for neuronal transduction studies [33].

- qPCR Reagents: For quantification of viral genome copies (using UL5 gene primers) [33].

Methodology:

- Vector Construction:

- Using Red-mediated recombination, introduce Gateway cassette between LAP2/LATP2 and CTRL2 at the LAT locus (creating JΔNI8L-GW) or downstream of CTRS3 in the ICP4 locus (creating JΔNI84-GW) [33].

- Generate insulator-testing vectors by inserting combinations of viral and cellular insulators flanking the CAG-ZsG/fLuc reporter cassette at both loci.

- Produce viral vectors by transfecting BAC DNA into U2OS-ICP4/27 complementing cells. Determine biological titer (pfu/mL) by plaque assay and physical titer (genome copies/mL) by qPCR for the UL5 gene [33].

In Vitro Transduction and Expression Analysis:

- Differentiate SH-SY5Y cells using all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) to obtain a homogeneous neuronal-like population.

- Transduce cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5000 gc/cell. Analyze transgene expression at 3, 14, and 21 days post-infection (dpi) via fluorescence microscopy for ZsGreen and luciferase activity assays [33].

- Compare expression levels between LAT and ICP4 loci, and assess the effect of added cellular insulators.

In Vivo Expression and Persistence:

- Administer vectors expressing the best-performing insulator configurations into rodent brain.

- Monitor transgene expression longitudinally for at least 4-12 months using appropriate imaging modalities and biochemical assays.

- Quantify expression stability over time and compare with vectors lacking enhanced insulator protection.

The workflow for this experimental approach to test insulator function in viral vectors is outlined below.

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Evaluating Insulator Function

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Advancing viral vector research requires specialized reagents and systems designed to address the unique challenges of vector production, quantification, and functional assessment. This toolkit highlights critical materials referenced in the experimental data.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Vector Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Function | Experimental Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CTCF-Binding Insulator Elements | Recruit chromatin remodeling factors to prevent heterochromatin formation and epigenetic silencing [33] | Maintain transgene expression in rdHSV-1 vectors by positioning near transgene cassettes [33] |

| Cellular Insulators (tRNA, S/MAR) | Provide border functions that shield transgene promoters from repressive chromosomal environments [33] | Enhance and prolong neuronal transgene expression when combined with viral insulators in rdHSV-1 [33] |

| Complementing Cell Lines (U2OS-ICP4/27) | Provide essential viral genes in trans for propagation of replication-defective vectors [33] | Production of IE gene-deficient HSV-1 vectors without generating replication-competent virus [33] |