What Causes Cell Culture Contamination? A Complete Guide to Sources, Prevention, and Control

Cell culture contamination is a critical challenge that compromises experimental integrity, data reproducibility, and patient safety in biopharmaceutical production.

What Causes Cell Culture Contamination? A Complete Guide to Sources, Prevention, and Control

Abstract

Cell culture contamination is a critical challenge that compromises experimental integrity, data reproducibility, and patient safety in biopharmaceutical production. This comprehensive article explores the multifaceted causes of contamination, from common biological agents like bacteria, mycoplasma, and fungi to chemical contaminants and cross-contamination. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides actionable methodologies for detection, robust troubleshooting and optimization strategies for prevention, and validation frameworks to ensure culture purity and regulatory compliance across both research and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) environments.

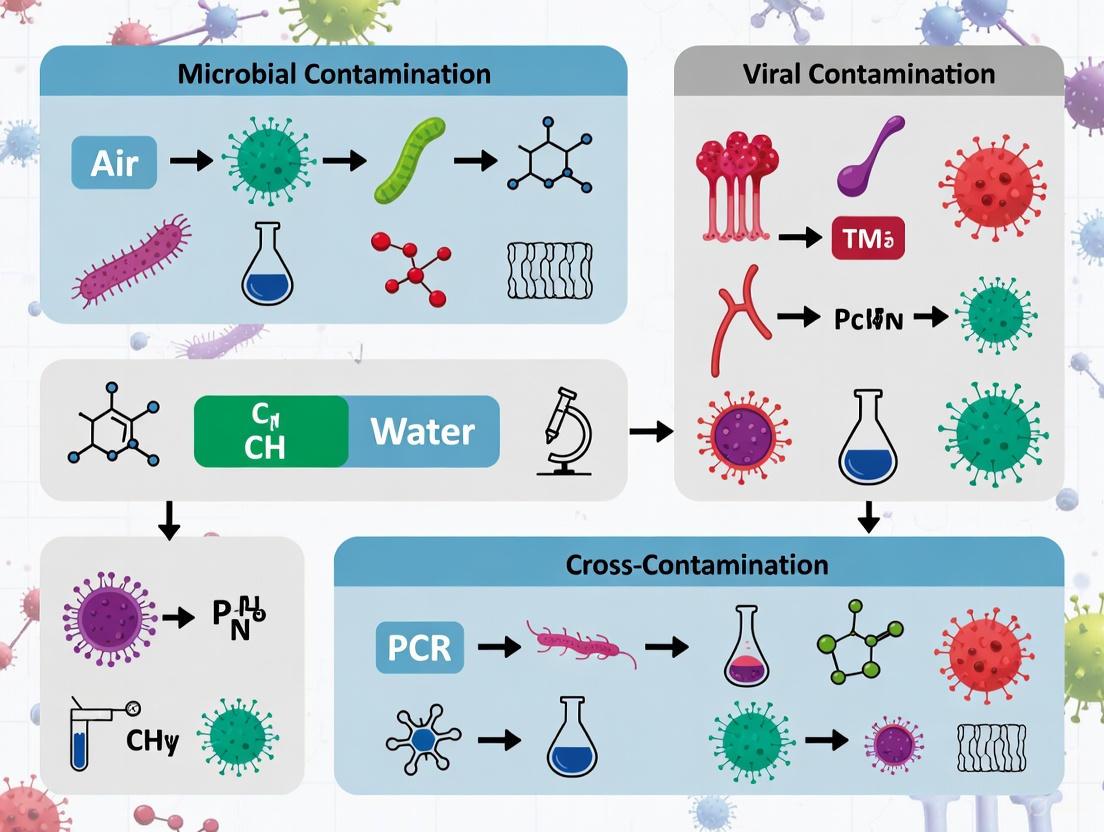

Unseen Enemies: Understanding the Spectrum of Cell Culture Contaminants

Biological contamination represents one of the most persistent and costly challenges in cellular and molecular biology research, particularly in pharmaceutical preclinical studies and biotechnological production. Microbial contaminants—including bacteria, fungi, yeast, and mold—can compromise experimental integrity, lead to irreproducible results, and jeopardize patient safety in drug development pipelines. These contaminants compete with cultured cells for nutrients, alter their microenvironment, and can introduce confounding variables that invalidate research findings. The cultivation of cells in an artificial environment removes the protective mechanisms of the immune system, leaving them vulnerable to microorganisms that are ubiquitous in laboratory settings. Consequently, understanding the sources, characteristics, and control mechanisms for these biological contaminants is fundamental to maintaining the sterility and quality assurance required for rigorous scientific research.

Within the broader context of cell culture contamination research, biological contaminants represent the most frequent and disruptive category, with estimates suggesting that problematic cell lines have contributed to approximately 16.1% of published literature [1]. The economic implications are substantial, as a single contamination event can compromise months of work and valuable reagents. More importantly, certain contaminants like mycoplasma can remain undetected while subtly interfering with cellular processes, potentially leading to false conclusions in basic research and dangerous outcomes in translational applications. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the primary biological contaminants, their identification, experimental protocols for detection and eradication, and emerging technologies that promise to revolutionize contamination monitoring in cell culture systems.

Characteristics of Major Biological Contaminants

Biological contaminants in cell culture vary significantly in their physical characteristics, growth requirements, and effects on cultured cells. Accurate identification is crucial for implementing appropriate eradication protocols and preventing future contamination events. The most prevalent contaminants include diverse bacteria, fungi (encompassing both yeasts and molds), and mycoplasma, each with distinct morphological features and impacts on cell culture systems.

Bacterial Contamination

Bacterial contamination represents one of the most common and rapidly destructive sources of experimental compromise in cell culture laboratories. Bacteria can enter cultures through unclean surfaces, contaminated reagents, insufficiently sterilized labware, or breaches in aseptic technique. The effects are typically fast and readily noticeable to a trained eye. Under microscopic examination, bacterial contaminants appear as small (approximately 1–5 µm), motile particles that often exhibit a "quicksand-like" movement between cultured cells [2] [3]. Culture medium often turns yellowish due to a rapid drop in pH resulting from bacterial metabolic activity, and the medium may appear cloudy or turbid when contamination becomes advanced. In some cases, an unpleasant or sour odor may be detectable upon opening contaminated culture vessels [3]. Bacterial contaminants can be broadly categorized by shape—spherical (cocci), rod-shaped (bacilli), or spiral—with each type potentially introducing different challenges for eradication.

Fungal Contamination: Yeasts and Molds

Fungal contamination encompasses both yeast and filamentous molds, which pose distinct challenges in cell culture systems. These eukaryotic contaminants grow more slowly than bacteria but still significantly faster than most mammalian cell cultures, making them persistent and aggressive once established.

Yeast Contamination: Yeasts are unicellular fungi characterized by round or oval morphology, with visible budding into smaller particles observed during microscopic examination. Initially, the culture medium may remain clear, but it typically turns yellowish over time as yeast metabolic activity affects pH [2]. Yeast contamination often originates from airborne spores, poorly maintained equipment, or contaminated reagents, and can be particularly problematic due to its resilience in laboratory environments.

Mold Contamination: Filamentous molds present as multicellular structures with characteristic thread-like hyphae that form visible networks in culture. Under microscopic examination, these thin, filamentous structures may develop dense spore clusters, while the culture medium may initially appear unchanged before becoming cloudy or developing fuzzy appearances at advanced stages [2]. Mold spores are ubiquitous in laboratory environments and can survive on surfaces or in the air for extended periods, making them particularly difficult to eradicate once established in a cell culture facility.

Mycoplasma Contamination

Mycoplasma species represent a particularly insidious category of biological contaminants due to their small size (approximately 0.3 µm) and lack of a cell wall [3]. These characteristics make them resistant to many standard antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis and allow them to pass through typical filters used for sterilization. Unlike other contaminants, mycoplasma does not cause visible turbidity or produce noticeable odor, allowing it to slip past routine visual checks [2] [3]. Under microscopic examination, mycoplasma may appear as tiny black dots, but cultures typically exhibit secondary indicators such as slow cell growth, abnormal morphology, reduced transfection efficiency, and unexplained changes in metabolic activity [2]. The real damage lies in its subtle interference with cellular processes—mycoplasma can alter DNA, inhibit cell division, or modify cytokine production, often without researchers realizing it until experimental data becomes inconsistent or irreproducible.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Biological Contaminants in Cell Culture

| Contaminant Type | Size Range | Visual Culture Indicators | Microscopic Morphology | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 1–5 µm | Yellowish, cloudy medium; possible odor | Spherical, rod-shaped, or spiral; motile particles | Rapid (hours) |

| Yeast | 3–10 µm | Initially clear, turns yellow over time | Round or oval cells, sometimes budding | Moderate (days) |

| Mold | Hyphae: 2–10 µm width | Initially unchanged, later cloudy or fuzzy | Thin, thread-like hyphae; dense spore clusters | Slow to moderate (days) |

| Mycoplasma | ~0.3 µm | No color change; no cloudiness | Tiny black dots; abnormal cell morphology | Slow (weeks) |

Detection and Identification Methodologies

Effective contamination control begins with reliable detection and identification methods. The optimal approach varies depending on the suspected contaminant type, available resources, and required sensitivity. The following experimental protocols represent current best practices for identifying biological contaminants in cell culture systems.

Microscopic Analysis

Direct microscopic observation serves as the first line of defense for detecting contamination in cell cultures. Regular inspection of cultures under phase-contrast microscopy should be incorporated into standard cell culture maintenance protocols.

Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Aseptically remove a small volume of cell culture medium from the vessel.

- Microscopic Examination: Observe under 100× to 400× magnification using phase-contrast microscopy.

- Bacterial Identification: Look for small, motile particles between cells exhibiting "quicksand-like" movement [2].

- Yeast Identification: Identify round or oval cells, typically 3–10 µm in diameter, with occasional budding structures [2].

- Mold Identification: Detect thin, thread-like hyphae that may form network structures; look for dense spore clusters in advanced contamination [2].

- Mycoplasma Indicators: While individual mycoplasma organisms are near the resolution limit of light microscopy, look for tiny black dots and secondary signs like granularity in the cytoplasm or abnormal cell morphology [2].

For enhanced visualization of contaminants, staining techniques such as Gram staining (for bacteria) or DNA-binding dyes like Hoechst 33258 (for mycoplasma) can be employed to improve contrast and specificity.

Culture-Based Detection Methods

Culture-based methods provide confirmatory evidence of contamination and are particularly valuable for identifying specific microbial species.

Protocol for Broth Culture Detection:

- Sample Preparation: Aseptically collect 1–2 mL of potentially contaminated cell culture supernatant.

- Inoculation: Transfer 0.5 mL of supernatant into sterile nutrient broth (for bacteria) or Sabouraud dextrose broth (for fungi).

- Incubation: Incubate inoculated broths at 37°C (for mammalian culture contaminants) and 25–30°C (for environmental fungi) for 24–72 hours.

- Assessment: Observe broths daily for turbidity (bacteria) or surface growth (fungi), which indicates positive contamination.

- Subculturing: For identification, streak positive broths onto appropriate agar plates (blood agar for bacteria, Sabouraud dextrose agar for fungi) to obtain isolated colonies.

- Analysis: Examine colony morphology, perform Gram staining, and conduct biochemical tests as needed for species identification.

Molecular Detection Methods

Molecular techniques offer superior sensitivity and specificity for detecting contaminants, particularly for challenging organisms like mycoplasma.

PCR Protocol for Mycoplasma Detection:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from 1–2 mL of cell culture supernatant using commercial DNA extraction kits according to manufacturer instructions.

- Primer Design: Use primers targeting conserved mycoplasma genes (e.g., 16S rRNA gene). Common sequences include:

- Forward: 5'-ACACCATGGGAGCTGGTAAT-3'

- Reverse: 5'-CTTCWTCGACTTYCAGACCCAAGGCAT-3'

- PCR Reaction Setup:

- Template DNA: 2–5 µL

- Primer mix (10 µM each): 1 µL

- PCR master mix: 12.5 µL

- Nuclease-free water to 25 µL total volume

- Amplification Parameters:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes

- 35 cycles of: 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 45 seconds

- Final extension: 72°C for 7 minutes

- Analysis: Separate PCR products by gel electrophoresis (1.5–2% agarose); positive detection indicated by bands of expected size (approximately 500 bp for many mycoplasma species).

Commercial mycoplasma detection kits are available that provide optimized protocols and reagents, such as the MycAway Plus Color One-Step Mycoplasma Detection Kit, which can provide results in approximately 30 minutes [2].

Emerging Detection Technologies

Advanced detection methodologies are revolutionizing contamination monitoring by enabling earlier identification through innovative approaches.

Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Analysis: Emerging technologies utilize gas chromatography with ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) to detect volatile organic compounds released by contaminating microorganisms [4]. This approach can detect as low as 10 colony-forming units (CFU) of various bacteria and mold species within just two hours post-inoculation, and mycoplasma contamination within 24 hours [4]. The methodology involves:

- Headspace Sampling: Collecting gas samples from the headspace of culture vessels.

- GC-IMS Analysis: Separating and detecting VOC profiles characteristic of specific contaminants.

- Pattern Recognition: Using machine learning algorithms to identify contamination-specific VOC signatures.

Real-Time Sensor Monitoring: Semiconductor-based sensors for total volatile organic compounds (TVOC), ammonia, and hydrogen sulfide can be implemented for real-time monitoring directly inside cell culture incubators [5]. This approach demonstrated potential for detecting bacterial contamination within a 2-hour window from onset, providing continuous sterility assurance during culture development [5].

Table 2: Detection Methods for Biological Contaminants

| Detection Method | Target Contaminants | Time to Result | Sensitivity | Special Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Microscopy | Bacteria, yeast, mold | Immediate | Low to moderate | Phase-contrast microscope |

| Culture Methods | Bacteria, fungi | 24–72 hours | Moderate | Culture media, incubators |

| PCR-Based Detection | Mycoplasma, specific bacteria | 2–4 hours | High (≤10 CFU) | Thermal cycler, specific primers |

| VOC Analysis (GC-IMS) | Bacteria, mold, mycoplasma | 20 minutes–24 hours | High (10 CFU) | Specialized instrumentation |

| Fluorescence Staining | Mycoplasma, bacteria | 1–2 hours | Moderate | Fluorescence microscope |

| ELISA | Specific pathogens | 3–5 hours | Moderate | Specific antibodies |

Eradication and Management Protocols

Once contamination is identified, appropriate response protocols are essential to minimize impact and prevent spread. The optimal approach depends on the contaminant type, value of the affected cells, and facility resources.

Bacterial Contamination Management

For Mild Bacterial Contamination:

- Washing: Gently wash cell monolayer with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove loose bacteria [2].

- Antibiotic Treatment: Replace medium with fresh culture medium containing 10× penicillin/streptomycin combination [2].

- Monitoring: Observe cultures closely for 24–48 hours for signs of continued contamination.

- Passaging: If contamination appears controlled, passage cells and return to standard antibiotic-free media or maintenance-level antibiotics.

For Heavy Bacterial Contamination:

- Containment: Immediately seal contaminated vessels to prevent aerosolization.

- Disposal: Autoclave contaminated cultures before disposal.

- Decontamination: Thoroughly disinfect incubator surfaces, work areas, and water baths with appropriate sporicidal agents [2].

- Equipment Testing: Check and service biological safety cabinets to ensure proper function.

Fungal Contamination Management

Yeast Contamination:

- Recommended Approach: Discard contaminated cultures immediately—this is typically the safest option [2].

- Potential Rescue Protocol (for valuable cultures only):

- Wash cells repeatedly with sterile PBS [2].

- Replace with fresh media containing 300 µg/mL fluconazole or amphotericin B [2].

- Note that amphotericin B is toxic to mammalian cells at effective antifungal concentrations.

- If contamination is controlled after 2–3 days, reduce antifungal concentration to 150 µg/mL for maintenance through 2–3 passages [2].

Mold Contamination:

- Immediate Discarding: Discard contaminated cells immediately due to spore formation risk [2].

- Incubator Decontamination:

- Preventive Measures: Add copper sulfate to the incubator water pan to discourage future fungal growth [2].

- Environmental Monitoring: Check HEPA filters in biological safety cabinets and culture room air handling systems.

Mycoplasma Eradication

Mycoplasma contamination presents unique challenges due to its resistance to common antibiotics and intracellular localization in some cases.

Antibiotic Treatment Protocol:

- Product Selection: Use commercial mycoplasma removal agents such as MycAway Solution for Cultured Cells [2].

- Treatment Duration: Typically requires 1–2 weeks of continuous exposure.

- Monitoring: Confirm eradication using PCR or DNA staining methods at least one week post-treatment.

- Quarantine: Maintain treated cells in quarantine with regular testing for at least one month.

Alternative Approaches:

- Passage in Mice: For hybridomas and some primary cells, passage in nude mice can eliminate mycoplasma contamination.

- Antibiotic Combinations:

- Use combinations of tetracycline, quinolones, or macrolides specifically formulated for mycoplasma eradication.

- Be aware that some agents may have cytostatic effects on mammalian cells.

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for contamination identification and management:

Prevention Strategies and Best Practices

Preventing contamination requires a systematic approach addressing multiple potential introduction points throughout the cell culture workflow. The following evidence-based strategies form a comprehensive prevention framework.

Aseptic Technique Mastery

Strict aseptic technique represents the foundation of contamination prevention in cell culture laboratories.

Critical Practices:

- Personal Protective Equipment: Always wear appropriate gloves, lab coats, and sleeves to establish a barrier between the technologist and the culture environment [2] [6].

- Proper Hood Usage: Work within a certified biological safety cabinet with verified HEPA filtration, maintaining proper airflow by not blocking air inlets or outlets [6].

- Surface Decontamination: Thoroughly disinfect all work surfaces with 70% ethanol or 70% industrial methylated spirits (IMS) before and after each procedure [6].

- Reagent Handling: Use sterile pipette tips, flasks, and reagents from trusted suppliers; filter-sterilize media through 0.2 µm membranes when appropriate [3] [6].

- Movement Minimization: Avoid unnecessary movements and talking in the hood to reduce air turbulence and potential contaminant introduction [2].

Environmental Control

Maintaining a controlled laboratory environment is essential for preventing contamination, particularly from airborne sources like mold spores.

Incubator Management:

- Regular Cleaning: Decontaminate CO₂ incubators weekly—including shelves, door gaskets, and water trays—using appropriate disinfectants [6].

- Water Pan Maintenance: Replace water in incubator water pans regularly and consider adding copper sulfate or other antifungal agents to discourage microbial growth [2].

- Temperature and Humidity Monitoring: Regularly calibrate and monitor incubator conditions to ensure stability.

- Segregation: Designate separate incubators for quarantined cultures, time-lapse imaging experiments, or other higher-risk applications [6].

Laboratory Design Considerations:

- Air Quality: Ensure proper HEPA filtration in cell culture rooms and biological safety cabinets.

- Traffic Patterns: Establish unidirectional workflow patterns from "clean" to "dirty" areas.

- Surface Materials: Use non-porous, easily cleanable surfaces for benches and equipment.

Quality Control Implementation

Systematic quality control procedures provide early detection of potential contamination issues before they compromise entire experiments.

Cell Line Management:

- Quarantine Protocol: Isolate and test all new cell lines for mycoplasma and other contaminants before integrating them into main culture areas [2] [3].

- Authentication: Perform regular cell line authentication using STR profiling or other methods to detect cross-contamination [1] [3].

- Cryopreservation: Maintain early-passage master stocks to preserve valuable lines against future contamination events.

- Documentation: Implement comprehensive labeling practices including cell line name, passage number, and date to facilitate traceability [6].

Reagent Quality Assurance:

- Supplier Qualification: Source media, serum, and supplements from reliable, tested suppliers with appropriate quality certifications [2].

- Aliquoting: Divide reagents into smaller working volumes to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles and limit cross-contamination potential [2].

- Expiration Monitoring: Implement first-in-first-out (FIFO) inventory systems and regularly check expiration dates.

- Sterility Testing: Periodically test media and supplements for microbial contamination, particularly for long-term experiments.

The following diagram illustrates the systematic approach to contamination prevention:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Effective contamination control requires specific reagents, equipment, and materials designed to prevent, detect, and eradicate biological contaminants. The following table details key solutions used in contamination management.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Management

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Protocol | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin/Streptomycin Solution | Bacterial prophylaxis and treatment | Add 1× concentration for prevention; 10× for eradication | Can mask low-level contamination; promotes antibiotic resistance with prolonged use [3] |

| Amphotericin B | Antifungal agent targeting yeasts and molds | Use at 2.5–5 µg/mL for prevention; higher concentrations (toxic to cells) for eradication | Cytotoxic to mammalian cells at concentrations needed for mold eradication [2] |

| Mycoplasma Removal Agents | Specific eradication of mycoplasma contamination | Continuous treatment for 1–2 weeks followed by confirmation testing | Multiple mechanisms of action including protein synthesis inhibition and DNA gyrase targeting [2] |

| Copper Sulfate | Fungistatic agent for incubator water pans | Add to incubator water reservoir at manufacturer-recommended concentration | Prevents fungal growth in humidified incubators without affecting cell growth [2] |

| 70% Ethanol | Surface decontamination | Spray and wipe all surfaces, gloves, and equipment entering biological safety cabinet | More effective than higher concentrations due to optimized penetration [6] |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kits | Rapid detection of mycoplasma contamination | PCR, enzymatic, or DNA staining protocols per manufacturer instructions | Some kits provide results in 30 minutes versus days for culture methods [2] |

| Benzalkonium Chloride | Strong disinfectant for equipment decontamination | Use for surface decontamination after mold contamination incidents | Effective against fungal spores; requires careful rinsing if used on culture equipment [2] |

| Filter Tips | Prevention of aerosol cross-contamination | Use for all liquid handling in cell culture procedures | Essential when working with multiple cell lines; prevents pipettor contamination [6] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of contamination control is rapidly evolving with advanced detection technologies and automated systems that promise to revolutionize cell culture practices.

Advanced Detection Platforms

Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Analysis: Gas chromatography with ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) represents a breakthrough in rapid contamination detection. This technology can identify bacterial contamination within 2 hours of onset and mycoplasma within 24 hours post-inoculation by analyzing signature volatile compounds [4]. The system requires minimal training, has a small laboratory footprint, and provides results in approximately 20 minutes per sample, making it ideal for integration into biomanufacturing workflows [4].

Real-Time Sensor Arrays: Semiconductor-based sensors for total volatile organic compounds (TVOC), ammonia, and hydrogen sulfide enable continuous, real-time monitoring directly within cell culture incubators [5]. Early research demonstrates the potential of TVOC sensors specifically for detecting bacterial contamination within a 2-hour window, paving the way for fully automated, non-invasive sterility assurance systems [5]. These systems could ultimately support scalability and efficiency in drug development processes without requiring human intervention for contamination monitoring.

Automated Cell Culture Systems

Automated cell culture platforms integrate multiple contamination control strategies, including:

- Closed Systems: Minimizing exposure to non-sterile environments through robotic handling in enclosed chambers.

- Continuous Monitoring: Implementing in-line sensors for real-time culture assessment.

- Algorithmic Detection: Using machine learning to identify subtle patterns indicative of early contamination.

These systems substantially reduce human-dependent variables in cell culture, potentially decreasing contamination frequency while improving reproducibility and standardization across laboratories.

Advanced Materials and Engineering Solutions

Innovative materials science approaches are contributing to contamination prevention through:

- Antimicrobial Surfaces: Incorporating copper alloys or antimicrobial polymers into incubator interiors and culture vessels.

- Smart Filtration: Developing self-sterilizing HEPA filters with photocatalytic coatings.

- Single-Use Systems: Implementing completely disposable bioreactor systems that eliminate cleaning validation and cross-contamination risks between runs.

These technological advances, combined with rigorous adherence to fundamental aseptic techniques, promise to significantly reduce the impact of biological contaminants on cell culture research and biomanufacturing in the coming years.

Mycoplasma contamination represents one of the most significant yet frequently overlooked challenges in cell culture laboratories worldwide. These minute bacteria, which lack a cell wall, surreptitiously infect cell cultures without obvious visual detection, primarily parasitizing cell surfaces and interfering with host cell functions [7]. With over 190 known species, only about 20 species of human, bovine, and porcine origin have been identified in cell culture, with eight particular species accounting for approximately 95% of all contamination incidents [8]. The sheer prevalence of this issue is staggering, with estimates suggesting that 15-35% of continuous cell cultures and at least 1% of primary cell cultures experience mycoplasma contamination [8]. The problem is particularly insidious because mycoplasma contamination often goes undetected while significantly altering cellular physiology, potentially compromising years of research and endangering the development of biopharmaceutical products [9] [10].

Within the broader context of cell culture contamination research, mycoplasma presents unique challenges that distinguish it from other contaminants. Unlike bacterial or fungal contamination, which often cause turbidity in media or noticeable pH shifts, mycoplasma contamination frequently escapes detection under standard light microscopy due to its small size (less than 300 nm) and does not cause media cloudiness [11] [12]. This stealthy nature, combined with its ability to profoundly influence virtually all aspects of cell physiology, establishes mycoplasma as a particularly dangerous "silent threat" that demands specialized detection methods and rigorous containment strategies [10] [8].

Biological Characteristics and Contamination Mechanisms

Unique Biological Features of Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma species belong to the class Mollicutes, representing the smallest self-replicating organisms known to date [12]. Their diminutive size, typically measuring less than 300 nanometers, allows them to readily pass through standard sterilizing filters with pore sizes of 0.45 μm, facilitating their unintended introduction into cell culture systems [12]. The most distinctive feature of mycoplasma is their complete lack of a cell wall, which renders them naturally resistant to common antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis, such as penicillin and its derivatives [8]. Instead, they are bounded only by a triple-layered cell membrane containing cholesterol, a characteristic more typical of eukaryotic cells than bacteria [8].

Mycoplasma possess extremely simplified genomes, which represent among the smallest of all free-living organisms [12]. This genomic reduction has resulted in limited metabolic capabilities, forcing them to become nutritional dependents on their host cells for survival [12]. Mycoplasma lack the genetic machinery to synthesize many essential nutrients and must therefore scavenge these compounds from their environment, primarily from the cell culture media and the host cells they infect [12]. This fundamental biological constraint explains their parasitic behavior in cell culture systems and their profound impact on host cell physiology.

While numerous mycoplasma species exist, only a limited subset commonly contaminates cell cultures. The eight species that account for the majority of contamination incidents include M. arginini (bovine), M. fermentans (human), M. hominis (human), M. hyorhinis (porcine), M. orale (human), M. pirum (human), M. salivarium (human), and Acholeplasma laidlawii (bovine) [8]. The species distribution of contaminants reflects common laboratory practices, with human-sourced species typically introduced through laboratory personnel and bovine-species often originating from contaminated serum supplements [8].

The primary sources and introduction routes of mycoplasma contamination in cell culture laboratories include:

- Human operators: Improper aseptic technique can transfer mycoplasma present on skin, clothing, or from airborne particles into cell cultures [12].

- Contaminated reagents: Animal sera, particularly fetal bovine serum, cell media, and other reagents can serve as contamination sources if not properly tested [8] [12].

- Cross-contamination: Already infected cell cultures can spread mycoplasma to clean cultures via shared equipment, media, or laboratory spaces [8].

- Laboratory equipment: Faulty laminar flow cabinets can disperse mycoplasma-containing dust and aerosols throughout the workspace [8].

Table 1: Major Mycoplasma Species in Cell Culture Contamination

| Species | Origin | Prevalence | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. arginini | Bovine | High | Common in fetal bovine serum |

| M. fermentans | Human | Moderate | Can affect multiple cell functions |

| M. hominis | Human | High | Frequent human carrier |

| M. hyorhinis | Porcine | Moderate | Common in porcine-derived materials |

| M. orale | Human | High | Prevalent in human oral flora |

| M. pirum | Human | Low | Less common but impactful |

| M. salivarium | Human | Moderate | Human oral and respiratory tract |

| A. laidlawii | Bovine | High | Common serum contaminant |

Detection Methodologies: Challenges and Advanced Approaches

Limitations of Conventional Detection Methods

Traditional methods for mycoplasma detection have significant limitations that can compromise their reliability. Direct culture methods, which involve inoculating agar plates with the test culture and incubating for four to five weeks to observe characteristic "fried egg" colonies, though considered a gold standard, are prohibitively time-consuming for routine testing [8]. DNA staining techniques using fluorescent dyes like Hoechst 33258 have been widely used but often yield equivocal results, primarily detecting only heavily contaminated cultures [7]. A critical limitation of conventional DNA staining is interference from host cell DNA; degraded DNA from host cells can produce small fluorescent spots under microscopy that mimic mycoplasma, leading to false positives or difficulties in interpretation [7].

The inherent challenges with these conventional approaches have driven the development of more sophisticated detection methodologies. As noted in recent research, "Cellular DNA interferes with the results of mycoplasma elimination when using DNA staining alone," highlighting the need for more specific detection strategies [7]. Furthermore, the silent nature of mycoplasma contamination means that visible signs often appear only after significant physiological damage has occurred to the cell culture, emphasizing the need for proactive, sensitive detection methods [11].

Advanced Detection Strategies

Colocalization Approach: DNA and Membrane Staining

A novel methodological advancement addresses the limitations of standalone DNA staining by combining DNA and cell membrane fluorescent dyes. This approach leverages colocalization analysis to accurately distinguish mycoplasma contamination from background cellular DNA. The technique involves staining cells with a combination of Hoechst (DNA dye) and WGA (wheat germ agglutinin, a membrane dye), then determining mycoplasma contamination by its specific colocalization with the plasma membrane surface [7].

The key advantage of this method is its ability to differentiate true mycoplasma contamination, which localizes to the cell membrane, from cytoplasmic DNA components that can cause false positives in conventional staining [7]. Research has demonstrated that this approach "minimized interference from cytoplasmic DNA components and greatly improved the accuracy of using DNA staining alone for mycoplasma detection" [7]. This colocalization method provides a rapid, direct screening technique that facilitates early diagnosis and treatment of contaminated cultures.

PCR-Based Detection Methods

Molecular methods based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology have emerged as the most reliable and efficient approach for mycoplasma detection. Modern PCR-based kits can detect over 60 species of mycoplasma, including the most common contaminants, with high sensitivity and specificity [9] [13]. These methods typically target the 16S rRNA gene in the mycoplasma genome, using universal PCR primers and specialized protocols to increase sensitivity [8] [13].

The significant advantages of PCR-based methods include:

- Rapid results: Time-to-results as short as 3 hours, compared to weeks for culture methods [13].

- High sensitivity: Detection limits of less than 10 CFU/ml for all mycoplasma species [13].

- Comprehensive coverage: Ability to detect a wide range of mycoplasma species in a single test [9].

- Regulatory compliance: Meets standards of European Pharmacopeia 2.6.7, USP <1071>, and JP G3 guidelines [8] [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Time to Result | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Culture | Growth on specialized agar | 4-5 weeks | High (theoretical gold standard) | Definitive identification | Extremely slow, specialized media required |

| DNA Staining | Fluorescent dye binding to DNA | 1-2 days | Low to moderate | Simple, inexpensive | Subjective, false positives from host DNA |

| Colocalization | Membrane and DNA dye combination | 1-2 days | Moderate to high | Reduces false positives, specific localization | Requires specialized analysis |

| PCR-Based | Amplification of mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences | 3 hours to 1 day | High (<10 CFU/ml) | Fast, sensitive, specific, comprehensive | Requires specialized equipment and expertise |

Experimental Protocol: Colocalization Method for Mycoplasma Detection

Principle: This protocol utilizes colocalization of DNA staining (Hoechst) and membrane staining (WGA) to accurately identify mycoplasma contamination localized to the host cell membrane, effectively mitigating false positives caused by cytoplasmic DNA [7].

Materials:

- Cell cultures (test and negative control)

- Hoechst 33258 or similar DNA-binding fluorescent dye

- WGA (wheat germ agglutinin) conjugated to a fluorescent marker with emission spectrum distinct from Hoechst

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde)

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS)

- Mounting medium

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets and colocalization analysis software

Procedure:

- Culture cells on appropriate sterile glass coverslips in cell culture plates until approximately 60-70% confluence.

- Aspirate culture medium and wash cells gently with pre-warmed PBS.

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash fixed cells three times with PBS, 5 minutes per wash.

- Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes.

- Prepare staining solution containing both Hoechst (at manufacturer's recommended concentration) and WGA conjugate.

- Incubate cells with staining solution for 30-60 minutes at room temperature protected from light.

- Wash stained cells three times with PBS, 5 minutes per wash.

- Mount coverslips on glass slides using appropriate mounting medium.

- Visualize using fluorescence microscopy with appropriate filter sets for each dye.

- Capture images of the same field under both fluorescence channels.

- Analyze images for colocalization of DNA signal (Hoechst) with membrane signal (WGA) at the cell surface.

Interpretation: Positive mycoplasma contamination is indicated by fluorescent DNA signal that colocalizes with the membrane stain at the cell surface. Cytoplasmic or nuclear DNA without membrane association suggests absence of mycoplasma or non-specific staining.

Impact of Mycoplasma Contamination on Cellular Functions

Comprehensive Physiological Disruption

Mycoplasma contamination exerts profound effects on virtually all aspects of cellular physiology, potentially compromising experimental results and leading to erroneous conclusions. The mechanisms underlying these disruptions stem from the parasitic relationship mycoplasma establishes with host cells, competing for essential nutrients and directly interacting with cellular components [8] [12]. The primary physiological impacts include:

Metabolic interference: Mycoplasma consume essential nutrients from the culture medium, including amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, nucleic acid precursors, and choline, effectively starving host cells of these critical components [12]. This nutrient competition can lead to altered metabolic profiles and impaired cellular growth.

Genetic and epigenetic alterations: Contamination can induce chromosomal aberrations and disrupt normal nucleic acid synthesis [8]. Mycoplasma infection has been demonstrated to cause changes in gene expression profiles, potentially skewing results in transcriptomic studies and other gene expression analyses [8].

Membrane and signaling effects: The presence of mycoplasma can alter membrane antigenicity and interfere with receptor signaling pathways [8]. These changes can affect cellular communication, transport mechanisms, and response to experimental treatments.

Proliferation and viability impacts: Mycoplasma contamination frequently inhibits cell proliferation and metabolism, eventually leading to increased cell death under prolonged infection [8]. The progressive nature of these effects means that experimental results may deteriorate over time, creating inconsistencies between experiments.

Technology-specific interference: Mycoplasma infection can decrease transfection rates and adversely affect virus production in systems designed for viral vector production [8]. These technology-specific effects can undermine specialized applications and production systems.

Implications for Research and Bioprocessing

The consequences of mycoplasma-induced physiological disruptions extend throughout the research and development pipeline. In basic research, contamination can lead to misinterpretation of results, false conclusions, and irreproducible findings, potentially invalidating entire research programs [10]. One analysis noted that mycoplasma can "affect the phenotypic and functional characteristics of cells in vitro," highlighting the pervasive nature of its effects [8].

In the context of biopharmaceutical development and production, the implications are even more severe. Contamination of cell substrates used in production poses potential safety risks for patients and presents serious economic risks through batch adulteration or product recalls [9] [8]. The compromised cellular functions can alter critical quality attributes of biopharmaceutical products, affecting both efficacy and safety profiles.

Prevention and Elimination Strategies

Proactive Prevention Protocols

Preventing mycoplasma contamination requires a comprehensive approach addressing multiple potential introduction routes. Effective prevention strategies include:

Strict aseptic techniques: Proper training in aseptic techniques forms the foundation of contamination prevention. This includes maintaining uncluttered cell culture hoods, spraying items with 70% ethanol before introduction into the hood, keeping plates and bottles covered, and avoiding movements that compromise air flow [10].

Personal protective equipment (PPE): Consistently wearing proper PPE, including gloves and clean lab coats (changed at least weekly), reduces potential human-derived contamination [10] [8].

Environmental control: Regular cleaning of incubators with bleach, changing or cleaning water pans weekly, and maintaining certified vertical laminar flow hoods minimize environmental contamination risks [10] [8].

Quarantine procedures: New or previously untested cell lines should be maintained in a designated incubator separate from established cultures until confirmed mycoplasma-free through testing [10]. This practice prevents cross-contamination of valuable cell stocks.

Quality reagent sourcing: Confirming that all media, sera, and reagents come from mycoplasma-free sources safeguards cells from contamination by external materials [8]. Using sterile single-use consumables whenever possible reduces introduction risks.

Routine testing: Implementing a schedule for periodic mycoplasma testing, including testing whenever freezing new cell banks, ensures early detection of potential contamination events [10].

Elimination and Decontamination Approaches

Once mycoplasma contamination is detected, prompt action is necessary to prevent laboratory-wide spread:

Immediate quarantine: Separating contaminated cultures from vulnerable cells is the critical first step [10]. All equipment and materials exposed to the contaminated culture should be identified and properly decontaminated.

Antibiotic treatment: Specialized antibiotics effective against mycoplasma, such as Plasmocin, are typically administered at 25 μg/mL for one to two weeks [10]. Importantly, conventional antibiotics like penicillin are ineffective against mycoplasma due to their lack of a cell wall [8].

Post-treatment verification: After completing antibiotic treatment, cells must be cultured without antibiotics for one to two weeks and then re-tested to confirm elimination success [10]. This antibiotic-free period is essential as it allows low-level persistent contaminants to proliferate to detectable levels.

Decision points: If post-treatment testing remains positive, options include repeated antibiotic treatment with extended duration, trying alternative antibiotics, or discarding the culture depending on the cell line's value and persistence of contamination [10].

Comprehensive decontamination: All laboratory surfaces, incubators, and equipment exposed to the contaminated culture require thorough decontamination with appropriate sporicidal agents to prevent recurrence [11].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mycoplasma Detection and Prevention

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Detection Kits | Rapid, sensitive detection of mycoplasma DNA | Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit (ATCC), Venor Mycoplasma Detection (Minerva) | Detects >60 species, 3-hour protocol, sensitivity <10 CFU/ml |

| Fluorescent Stains | Visual detection via DNA binding | Hoechst 33258, DAPI | DNA-specific fluorescence, requires fluorescence microscopy |

| Membrane Stains | Cell membrane labeling for colocalization | WGA (wheat germ agglutinin) conjugates | Specific membrane binding, different fluorophore options |

| Antibiotic Treatments | Elimination of contamination | Plasmocin, Enrofloxacin | Effective against mycoplasma, different mechanisms |

| Positive Controls | Assay validation and calibration | Quantitative genomic DNA from M. hominis, M. pneumoniae | Certified reference materials, known concentrations |

| Reference Strains | Assay development and validation | Titered mycoplasma reference strains | Calculated genome copy numbers, panel of common species |

| Growth Supplements | Culture-based detection enhancement | Mycoplasma growth supplement | Enhances recovery in broth and agar media |

| Decontamination Agents | Laboratory surface purification | Bleach, specialized sporicidal agents | Effective against mycoplasma on equipment and surfaces |

Mycoplasma contamination remains a persistent and formidable challenge in cell culture laboratories, representing a silent threat that can compromise years of research and development efforts. The unique biological characteristics of these microorganisms—including their small size, lack of cell wall, and stealthy infection patterns—require specialized detection methods beyond conventional microbiological approaches. Advanced techniques such as PCR-based detection and colocalization staining provide the sensitivity and specificity needed for reliable identification, while comprehensive prevention protocols centered on rigorous aseptic technique and routine monitoring form the first line of defense.

The profound impact of mycoplasma contamination on virtually all aspects of cellular physiology underscores the critical importance of vigilant monitoring and rapid response strategies. From altered metabolic pathways and genetic expression changes to compromised experimental results and potential product safety concerns, the consequences of undetected contamination can be far-reaching. As cell culture technologies continue to advance and play increasingly important roles in biopharmaceutical development and regenerative medicine, maintaining mycoplasma-free cultures becomes ever more essential. Through implementation of the detection, prevention, and elimination strategies outlined in this review, researchers can protect their cellular models, ensure the integrity of their data, and safeguard the translation of their findings into meaningful scientific and clinical advancements.

Viral contamination represents a persistent and covert threat to the integrity of biological research and the safety of biopharmaceutical manufacturing. Unlike bacterial or fungal contamination, viral contaminants can be difficult to detect, often escaping notice until they have compromised experimental results or entire production batches [14] [11]. In cell culture systems, which are fundamental to modern biological research and therapeutic production, viral infections can alter cellular metabolism, gene expression, and viability, potentially leading to misleading scientific conclusions or dangerous therapeutic products [14].

The implications of viral contamination extend beyond scientific accuracy to encompass significant economic and health consequences. Historical incidents of viral transmission through biological products have led to patient harm, highlighting the critical importance of robust viral safety strategies [15] [16]. This technical guide examines the sources, detection methods, and prevention strategies for viral contamination, providing researchers and bioprocessing professionals with a comprehensive framework for safeguarding their work against these invisible threats.

Viral contamination in cell culture systems can originate from multiple sources, which regulatory guidelines broadly categorize into two groups: endogenous contaminants present in cell banks, and adventitious viruses introduced during production [17].

Cell Banks and Raw Materials: Master Cell Banks (MCBs) and Working Cell Banks (WCBs) can harbor endogenous viruses, particularly retroviruses, which are constitutively expressed and transmitted through sequential cell passage [17]. Raw materials of animal origin, such as bovine serum or porcine-derived trypsin, historically represent significant contamination risks [15] [16]. Although the industry has shifted toward animal-component-free media, risks persist from contaminated reagents or inadequate sterilization [18].

Production Process Introduction: Adventitious viruses can be introduced during manufacturing through handling of cell cultures, contaminated raw materials, or operator error [17] [15]. The case study of baculovirus contamination in a BEVS manufacturing process illustrates how simultaneous operations in shared facilities can lead to cross-contamination, even with spatial segregation [18]. In this incident, the same operator working on both virus harvest and media preparation activities likely facilitated the transfer of concentrated virus into host-cell media, resulting in multiple batch failures.

Environmental and Human Factors: Laboratory environments, including unfiltered air, unclean surfaces, and improper airflow control, can serve as contamination vectors [11]. Human operators remain a potential source through improper aseptic techniques, inadequate training, or failure to follow standard operating procedures [11].

Historical Context and Impact

Historical contamination events underscore the serious consequences of viral contamination:

Figure 1: Consequences of Viral Contamination and Historical Examples

Notably, before implementation of viral inactivation procedures, hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 were transmitted to patients through human-plasma-derived biological products [15]. While no infectious virus has been transmitted to patients by biopharmaceuticals derived from cell lines, contamination events have been detected in process intermediates, leading to significant economic losses and product shortages [15].

Detection and Identification of Viral Contaminants

Effective detection of viral contamination requires a multi-faceted approach, as no single method can identify all potential contaminants. The selection of detection methodologies depends on the type of virus, the stage of production, and the required sensitivity.

Established Detection Methods

Cytopathic Effects (CPE) Observation: Many viruses induce visible morphological changes in infected cells, known as cytopathic effects [14]. These can include cell rounding, syncytia formation (cell fusion), and cell lysis. For example, HSV-2 infection in A549 cells causes significant rounding and detachment from the culture surface [14]. While CPE observation provides an initial indication of contamination, many viruses, particularly latent ones, do not produce obvious cytopathic effects.

PCR-Based Assays: Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods, including quantitative PCR (qPCR), offer highly sensitive and specific detection of viral nucleic acids [14]. These assays can identify both active and latent viral forms, making them particularly valuable for detecting viruses like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which infects approximately 98% of the human population [14]. PCR is especially crucial for detecting mycoplasma contamination, which doesn't cause turbidity or other obvious signs but alters gene expression and cellular function [11].

In Vitro and In Vivo Virus Assays: Broad-specificity in vitro assays using indicator cell lines can detect a wide range of viral contaminants through observation of CPE or immunochemical staining [17]. In vivo assays, involving inoculation of samples into animals such as mice or embryonated eggs, provide a complementary approach for detecting viruses that may not grow in standard cell cultures [17].

Emerging Detection Technologies

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) enables comprehensive detection of known and unknown viral contaminants without prior knowledge of the viral sequence [17]. This untargeted approach is particularly valuable for identifying emerging contaminants or viruses not previously associated with cell culture systems. The "Blazar Platform" represents an example of rapid molecular testing methods that enable real-time decisions on in-process materials [17].

Table 1: Viral Detection Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytopathic Effect Observation | Visual identification of virus-induced morphological changes | Variable; depends on virus | Initial screening; virus identification | Insensitive to non-cytopathic viruses |

| PCR/qPCR | Amplification of viral nucleic acids | High (can detect few copies) | Specific virus detection; latency identification | Requires prior knowledge of viral sequence |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | High-throughput sequencing of all nucleic acids | High | Comprehensive detection; unknown viruses | Cost; complex data analysis |

| In Vitro Virus Assays | Infection of permissive indicator cell lines | Moderate to high | Broad virus detection | Limited by cell line permissiveness |

Prevention and Control Strategies

A comprehensive viral safety strategy employs multiple complementary approaches to prevent contamination from entering bioprocessing systems and to manage risks throughout production.

Prevention Framework

The foundational framework for viral safety involves three key elements: prevention, detection, and removal [17]. Prevention focuses on careful selection of cells and raw materials, with preference for animal-derived component-free materials wherever possible [17]. For raw materials that cannot be eliminated, sourcing from low-risk geographies or using materials treated with gamma irradiation, UV irradiation, or high-temperature short-time (HTST) pasteurization reduces contamination risk [17].

Closed Processing Systems: Implementing closed bioprocessing technologies provides a higher level of process protection than open processing by isolating the process and product from environmental contaminants [18]. Functionally closed systems, appropriately validated, can allow manufacturing in controlled, non-classified environments because the surrounding environment no longer affects the process [18].

Environmental and Personnel Controls: Strict cleanroom standards utilizing HEPA filtration, proper gowning procedures, and comprehensive environmental monitoring programs are essential for controlling contamination risks [11]. Well-trained operators following established aseptic techniques represent a critical defense against adventitious viral introduction [11].

Testing Strategy

A comprehensive testing strategy covers all aspects of the production process, from raw materials to final product. According to ICH Q5A guidance, Master Cell Bank (MCB) characterization requires broad specificity in vitro and in vivo virus assays, while Working Cell Banks (WCB) undergo more limited testing [17]. End-of-production (EOP) cells are tested extensively for viral contaminants that may be present but not detected in the MCB [17].

Figure 2: Comprehensive Viral Risk Management Framework

Viral Clearance and Inactivation Methodologies

Despite rigorous prevention efforts, the risk of viral contamination cannot be entirely eliminated, making viral clearance steps essential components of biopharmaceutical manufacturing processes. Viral clearance studies demonstrate the capability of manufacturing processes to remove or inactivate potential viral contaminants.

Viral Clearance Study Design

Viral clearance studies are performed using scaled-down models that accurately represent actual manufacturing processes [15]. To ensure validity, these scaled-down models must mimic full-scale processes in terms of buffers, linear flow rates, contact times, and other critical parameters [15]. Product and impurity profiles from scaled-down processes must reflect those from full-scale manufacturing for viral clearance data to be considered valid [15].

For early-stage clinical trials, the European Medicines Agency requires a minimum evaluation of two orthogonal steps with a retrovirus and a parvovirus [15]. As product development advances toward licensure, more comprehensive studies are performed with an extended virus panel under a range of processing conditions, including worst-case parameters [15].

Viral reduction is typically expressed in logarithmic terms (log10 reduction), calculated by comparing the amount of virus in preprocessed load material to that in post-processed samples [15]. Cumulative process reduction values are determined by summing the log reduction levels for each unit operation.

Viral Clearance Technologies

Effective viral clearance employs orthogonal methods with different mechanisms of action to ensure robust viral safety.

Low pH Treatment: Exposure to low pH (e.g., pH 3.0–3.6) is highly effective against enveloped viruses and is commonly used in monoclonal antibody purification processes following Protein A chromatography [17] [15]. This method provides robust viral reduction, typically exceeding 4.0 log10 for enveloped viruses [15].

Solvent/Detergent Treatment: Originally developed for blood products, solvent/detergent treatment using combinations such as 0.3% tri(n-butyl) phosphate/0.2% sodium cholate effectively inactivates enveloped viruses by disrupting their lipid membranes [15]. This method is robust and effective against a wide range of enveloped viruses.

Virus Filtration: Virus-retentive filters physically remove viruses based on size exclusion [17] [15]. These filters are particularly valuable for removing small, non-enveloped viruses such as parvoviruses, which are resistant to many inactivation methods [17]. Virus filtration is considered a robust clearance method when properly validated and operated within specified parameters.

Chromatography Operations: Although optimized for product purification, chromatography steps often provide incidental viral clearance through a combination of mechanisms, including binding to resin surfaces, degradation during elution, and separation from the product [15]. Anion-exchange chromatography can be optimized to provide significant viral clearance, though chromatography steps are generally less robust than dedicated viral clearance operations [15].

Table 2: Viral Clearance Methods and Their Effectiveness

| Method | Mechanism | Virus Types Affected | Typical Log Reduction | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low pH Treatment | Denaturation of viral envelope proteins | Enveloped viruses | >4.0 log10 | Effectiveness depends on pH, time, temperature |

| Solvent/Detergent | Disruption of viral lipid envelope | Enveloped viruses | >4.0 log10 | Ineffective against non-enveloped viruses |

| Virus Filtration | Size-based exclusion | All viruses larger than pore size | >4.0 log10 | Filter integrity critical; fouling concerns |

| Anion-Exchange Chromatography | Binding to resin surfaces | Enveloped and non-enveloped | 2-4 log10 | Highly dependent on process conditions |

Experimental Protocols for Viral Detection and Clearance Validation

Protocol for Viral Detection in Cell Banks

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for detecting viral contaminants in cell banks using a combination of in vitro and in vivo assays, as recommended by regulatory guidelines [17].

Sample Preparation: Collect approximately 10^7 cells from the cell bank. Prepare cell lysates by freeze-thaw cycling or chemical lysis. For co-cultivation assays, prepare viable cells for co-cultivation with indicator cell lines.

In Vitro Assay: Inoculate samples onto at least three different indicator cell lines, including human and non-human primate cell lines known to support growth of a wide range of viruses. Maintain cultures for at least 14 days with at least one subculture during this period. Observe regularly for cytopathic effects. Include positive controls with known viruses to demonstrate assay sensitivity.

In Vivo Assay: Inoculate samples into at least two animal systems, typically suckling mice and embryonated eggs. Observe animals for signs of disease or mortality. Examine embryos for evidence of viral replication after appropriate incubation.

Other Virus-Specific Tests: Perform specific tests for retroviruses and other known contaminants. For retroviruses, use reverse transcriptase assays or transmission electron microscopy. For specific viruses of concern (e.g., EBV, OvHV-2), implement PCR-based assays with appropriate controls [14].

Results Interpretation: A sample is considered positive if any test system shows evidence of viral presence. Negative results across all assays provide confidence in the viral safety of the cell bank, though they do not guarantee absolute absence of viral contaminants.

Protocol for Viral Clearance Studies

This protocol describes the general approach for validating the viral clearance capability of manufacturing process steps, following regulatory expectations [15].

Scale-Down Model Qualification: Before viral clearance studies, qualify the scaled-down model by demonstrating that it accurately represents the full-scale manufacturing process. Compare critical process parameters (flow rates, contact times, buffer compositions) and performance indicators (step yield, product quality attributes) between scales.

Virus Panel Selection: Select a panel of relevant model viruses representing different virus types and characteristics. Typical panels include:

- Murine Leukemia Virus (MuLV) as a model for endogenous retroviruses

- Minute Virus of Mice (MVM) or other parvoviruses as models for small, non-enveloped viruses

- Additional viruses based on risk assessment, potentially including pseudorabies virus, bovine viral diarrhea virus, or others

Virus Spike Preparation: Prepare high-titer virus stocks in appropriate matrices. Characterize virus stocks for titer and purity. Determine the appropriate spike ratio (typically 1-10% v/v) to ensure it does not significantly alter product or process stream characteristics.

Process Step Execution: Spike the virus into the preprocessed intermediate material. Execute the process step using predetermined operating parameters. Collect samples before processing and after completion of the step.

Virus Titration: Determine virus titers in pre- and post-processing samples using appropriate assays (plaque assay, 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50), or quantitative PCR). Include necessary controls to account for assay variability and toxicity.

Calculation of Viral Reduction: Calculate the log reduction value (LRV) using the formula: LRV = log10 (Vpre × Vvol.pre) - log10 (Vpost × Vvol.post), where Vpre and Vpost are virus titers in pre- and post-processing samples, and Vvol.pre and Vvol.post are sample volumes.

Data Interpretation and Reporting: Report individual LRVs for each virus and process step combination. Evaluate the overall clearance capacity of the process by summing LRVs from orthogonal steps. Discuss limitations and assumptions of the study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementing effective viral safety programs requires specific reagents, materials, and systems designed to prevent, detect, or remove viral contaminants.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Safety

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Virus-Screened Fetal Bovine Serum | Cell culture supplement | Sourced from closed herds in low-risk geographical areas; tested for specific viruses |

| Animal-Derived Component Free Media | Cell culture medium | Eliminates risk from bovine- or porcine-derived materials; chemically defined formulations preferred |

| PCR/qPCR Kits for Virus Detection | Specific virus detection | Target common contaminants (e.g., mycoplasma, retroviruses, specific viruses of concern) |

| Indicator Cell Lines | Broad virus detection | Includes cell lines such as Vero, MRC-5, HEK293 with known susceptibility to various viruses |

| Virus Removal Filters | Physical removal of viruses | Size-based exclusion with pore sizes typically 20-50 nm; validated for specific retention ratings |

| Chromatography Resins | Product purification and virus removal | Anion-exchange resins particularly effective for virus removal under appropriate conditions |

| Solvent/Detergent Reagents | Viral inactivation | TNBP/Triton X-45 or polysorbate 80/TNBP combinations for enveloped virus inactivation |

Viral contamination remains a persistent, covert risk to both biological research and biopharmaceutical production. The complex nature of viral contaminants, combined with the potential for devastating scientific, economic, and health consequences, necessitates comprehensive viral safety strategies integrating prevention, detection, and removal approaches. Implementation of robust quality control systems, including careful raw material selection, routine testing programs, and validated clearance steps, provides multilayered protection against these invisible threats.

As bioprocessing technologies evolve to include novel modalities such as cell and gene therapies, viral safety considerations must adapt to address new risk profiles. Maintaining vigilance against viral contamination through continued research, industry collaboration, and regulatory alignment will ensure the ongoing safety and efficacy of biological products while protecting the integrity of scientific research.

Cell culture contamination represents a significant challenge in biomedical research and biopharmaceutical production, potentially compromising experimental validity, product safety, and therapeutic efficacy. While microbial contamination receives considerable attention, chemical contaminants—specifically endotoxins, detergents, and media impurities—pose equally critical yet often less apparent risks. These contaminants can induce subtle but profound alterations in cellular responses, leading to unreliable data, failed experiments, and compromised biological products. This technical guide examines the sources, mechanisms, and impacts of these chemical contaminants within the broader context of cell culture contamination research, providing researchers with comprehensive methodologies for detection, removal, and prevention. Understanding these contaminants is essential for maintaining the integrity of in vitro systems and ensuring the reliability of research outcomes in drug development and basic science.

Endotoxin Contamination

Origins and Chemical Nature

Endotoxins, structurally known as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), are complex amphiphilic molecules constituting the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas [19]. Unlike exotoxins secreted by living bacteria, endotoxins are released primarily upon bacterial death and lysis, making sterilization processes potential contamination sources [20]. Structurally, LPS consists of three domains: a hydrophobic Lipid A moiety that anchors the molecule to the bacterial membrane, a core oligosaccharide, and a variable O-antigen polysaccharide chain [19]. The Lipid A component is responsible for the profound biological toxicity associated with endotoxins.

Mechanisms of Cellular Toxicity

Endotoxins exert their pathological effects primarily through activation of the innate immune system. The Lipid A component of LPS is recognized by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and its co-receptor MD-2 on immune cells such as monocytes and macrophages [19]. This recognition triggers intracellular signaling cascades leading to NF-κB activation and subsequent transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 [19]. At low levels, this response may cause subtle changes in cell behavior; at higher concentrations, it can induce fever, endotoxic shock, and cell death [19] [20].

Figure 1: Endotoxin (LPS) Signaling Pathway via TLR4 Activation

Detection and Quantification Methods

Accurate detection and quantification of endotoxins are essential for quality control in cell culture and bioprocessing. The Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay remains the gold standard, with several validated formats approved by regulatory agencies [19] [21].

Table 1: Endotoxin Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Applications | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gel-Clot LAL | Visual detection of gel formation | 0.03 EU/mL | Qualitative analysis | FDA approved [19] |

| Turbidimetric LAL | Measures turbidity increase | 0.001 EU/mL | Quantitative analysis | FDA approved [19] |

| Chromogenic LAL | Hydrolyzes chromogenic substrate | 0.005 EU/mL | Highly quantitative | FDA approved [19] |

| Rabbit Pyrogen Test | In vivo fever response | Varies | Systemic pyrogenicity | Being phased out [20] |

| Monocyte Activation Test (MAT) | Human cytokine release | 0.25 EU/mL | Detects all pyrogens | Alternative to animal testing [20] |

The Bacterial Endotoxins Test (BET) methodologies described in USP Chapter <85> and AAMI ST72 provide regulatory frameworks for testing [21]. For medical devices, endotoxin limits depend on the intended use, with more stringent requirements for devices contacting blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or other circulating fluids [20].

Removal and Control Strategies

Effective endotoxin control requires both removal from reagents and prevention of introduction. Removal techniques exploit the physicochemical properties of LPS and must be tailored to specific applications:

- Ion-Exchange Chromatography: Effective for separating negatively charged LPS from proteins [19]

- Affinity Adsorbents: Specific ligands target LPS structure [19]

- Triton X-114 Phase Separation: Exploits detergent properties to partition LPS [19]

- Sterilization Protocols: Dry heat at 250°C for >30 minutes or 180°C for 3 hours destroys endotoxins on glassware [22]

Preventive measures include using high-purity water (testing with LAL assay), selecting low-endotoxin FBS (<1ng/mL), and employing certified plasticware (<0.1 EU/mL) [22]. For organ-on-chip technologies fabricated with PDMS, oxygen plasma treatment can reduce endotoxin adsorption, though effects may diminish with hydrophobic recovery [23].

Detergent Contamination

Roles and Classifications in Cell Culture

Detergents are amphipathic molecules essential for various cell culture and protein biochemistry applications, including cell lysis, membrane protein solubilization, and preventing non-specific binding in affinity purification [24]. They are classified by the ionic character of their polar head groups:

- Ionic detergents (e.g., SDS): Charged head groups; strongly denaturing

- Non-ionic detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, NP-40): Uncharged; mild and non-denaturing

- Zwitterionic detergents (e.g., CHAPS): Both positive and negative charges; net neutral [24]

Table 2: Properties of Common Laboratory Detergents

| Detergent | Type | Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | Aggregation Number | Applications | Removability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS | Anionic | 6-8 mM (0.17-0.23%) | 62 | Strong lysis, denaturing | Difficult [24] |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic | 0.24 mM (0.0155%) | 140 | Mild lysis, membrane protein isolation | Dialysis/adsorption [24] |

| Tween-20 | Non-ionic | 0.06 mM (0.0074%) | - | Immunoassays, blocking | Dialysis [24] |

| CHAPS | Zwitterionic | 8-10 mM (0.5-0.6%) | 10 | Membrane protein solubilization | Dialyzable [24] |

| Octyl-glucoside | Non-ionic | 23-24 mM (~0.70%) | 27 | Protein crystallization | Highly dialyzable [24] |

Contamination Mechanisms and Impacts

Detergent contamination typically occurs through improper rinsing of laboratory ware, carryover from purification procedures, or misformulation of culture media. The impacts vary by detergent type and concentration:

- Ionic detergents like SDS denature proteins, disrupt membrane integrity, and cause complete cell lysis at low concentrations [24]

- Non-ionic detergents may interfere with receptor-ligand interactions, enzyme activities, and membrane protein functions without visible cell death [24] [25]

- Excess detergent micelles can block assay substrates, convolute analytical readings, and prevent protein crystallization [25]

Removal Techniques and Methodologies

Selecting appropriate detergent removal strategies depends on the detergent properties, sample volume, and intended downstream applications:

Figure 2: Detergent Removal Method Selection Workflow

Detailed Protocol: Styrene Bead Adsorption

- Principle: Porous polystyrene beads (e.g., Bio-Beads) adsorb detergent molecules through hydrophobic interactions [25].

- Procedure:

- Determine optimal bead-to-sample ratio empirically (typically 10-50 mg beads/100 μL sample)

- Add washed, wet beads to sample

- Incubate with gentle agitation for 2-4 hours at 4°C

- Centrifuge at 1000 × g for 2 minutes to pellet beads

- Carefully collect supernatant

- Repeat process if necessary

- Validation: Measure detergent concentration using iodine vapor staining with TLC and laser densitometry [25].

- Considerations: May co-remove essential lipids; risk of protein precipitation if detergent is over-removed [25].

Alternative Methods:

- Size-exclusion chromatography: Effective when protein and micelle sizes differ significantly [25]

- Dialysis: Suitable for detergents with high CMC; requires appropriate membrane selection [25]

- Detergent removal columns: Proprietary resins for rapid spin-column removal [25]

Media Impurities

Cell culture media contain multiple potential sources of chemical contaminants beyond endotoxins and detergents:

- Water impurities: Bacterial residues, ions, organic compounds from poorly maintained water purification systems [22]

- Serum components: High endotoxin levels in FBS, hormones, antibodies, viruses [22]

- Raw materials: Amino acid solutions with endotoxin levels as high as 50ng/mL, heavy metals, pesticides [22]

- Additives: Growth factors, cytokines, antibiotics with variable purity

- Leachables: Chemicals migrating from bioprocess containers or tubing

Impact on Cell Culture Systems

Media impurities can profoundly affect cellular responses and experimental outcomes:

- Altered growth kinetics: Subtle changes in proliferation rates without visible cytotoxicity

- Differentiation effects: Unplanned differentiation in stem cell cultures

- Gene expression changes: Modulation of inflammatory or stress response pathways

- Metabolic shifts: Altered nutrient utilization and waste production

- Morphological variations: Changes in cell shape, attachment, or organization

Detection and Quality Control

Implementing rigorous quality control measures for media and reagents is essential:

- Comprehensive testing: Beyond standard sterility testing to include endotoxin, mycoplasma, and viral contamination screens [14]

- Water quality monitoring: Regular LAL testing of water purification systems [22]

- Component qualification: Testing individual media components before full formulation

- Certified sourcing: Using manufacturers that provide comprehensive quality documentation

- In-process controls: Monitoring media throughout production and storage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LAL Reagents | Endotoxin detection and quantification | Choose format (gel-clot, chromogenic, turbidimetric) based on sensitivity needs [19] |

| Bio-Beads SM-2 | Hydrophobic adsorption of detergents | Optimal for Triton X-100 removal; requires ratio optimization [25] |

| Detergent Removal Columns | Rapid spin-column detergent removal | HiPPR and Pierce columns suitable for small volumes (<100μL) [25] |

| Low-Endotoxin FBS | Cell culture supplement with <1ng/mL endotoxin | Critical for sensitive cultures; premium grade available [22] |

| Certified Plasticware | Culture vessels tested for endotoxins | Typically <0.1 EU/mL; reduces introduction of contaminants [22] |

| Water for Injection (WFI) | High-purity water source | Alternative when laboratory water systems are compromised [22] |

| Recombinant Factor C (rFC) | Animal-free endotoxin testing | Eliminates horseshoe crab sourcing concerns; not yet FDA-approved [20] |

Integrated Contamination Control Strategy

Effective management of chemical contaminants requires a systematic, preventive approach rather than reactive measures. Implementation of Quality by Design (QbD) principles in research workflows helps identify critical control points for contamination prevention [21]. Key elements include:

- Comprehensive risk assessment: Evaluate all potential contamination sources from raw materials to final culture conditions

- Strategic sampling plans: Test in-process materials and finished products with dynamic sampling protocols that adapt as process knowledge increases [21]